W. E. B. Du Bois: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

add bibl |

||

| Line 122: | Line 122: | ||

==Articles by W.E.B. Du Bois== |

==Articles by W.E.B. Du Bois== |

||

[http://gutenberg.readingroo.ms/etext04/conra10.txt ''The American Negro Academy Occasional Papers'', 1897, No. 2 "The Conservation Of Races" full text] |

[http://gutenberg.readingroo.ms/etext04/conra10.txt ''The American Negro Academy Occasional Papers'', 1897, No. 2 "The Conservation Of Races" full text] |

||

==Further Reading== |

|||

* Eric J. Sundquist, ed.; ''The Oxford W.E.B. Du Bois Reader'' Oxford University Press. 1996 |

|||

* The Oxford W.E.B. Du Bois Reader. Contributors: Eric J. Sundquist - editor. Publisher: Oxford University Press. Place of Publication: New York. Publication Year: 1996. Page Number: iii. |

|||

* Broderick Francis L. ''W. E. B. Du Bois: Negro Leader in a Time of Crisis'' Stanford University Press, 1959. |

|||

* Horne Gerald. ''Black and Red: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Afro-American Response to the Cold War, 1944-1963'' State University of New York Press, 1986 |

|||

* David Levering Lewis. ''W. E. B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 1868-1919'' (1994), and vol 2: ''W. E. B. Du Bois: The Fight for Equality and the American Century, 1919-1963'' (2001) Pulitzer prize |

|||

* Meier August. ''Negro Thought in America, 1880-1915: Racial Ideologies in the Age of Booker T. Washington'' University of Michigan Press, 1963. |

|||

* Rampersad Arnold. ''The Art and Imagination of W. E. B. Du Bois''. Harvard University Press, 1976. |

|||

* Rudwick Elliott M. ''W. E. B. Du Bois: Propagandist of the Negro Protest''. 1960 |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 08:57, 10 May 2006

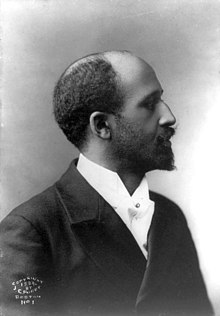

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was a civil rights activist, sociologist, educator, historian, writer, editor, poet, and scholar. He became a naturalized citizen of Ghana in 1963 at the age of ninety-five.

Biography

W.E.B. Du Bois was born at Church Street on February 23, 1868 in Great Barrington at the southwestern edge of Massachusetts to Alfred Du Bois and Mary Silvina Burghardt Du Bois, whose February 5, 1867 wedding had been announced in the Berkshire Courier. The birthplace of Alfred Du Bois was San Domingo, Haiti.[David Levering Lewis, W.E.B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 1868-1919] Their son was born one year after the Fourteenth Amendment [1] was ratified, and added to the U.S. Constitution. Alfred Du Bois was descended from free people of color, descended from Dr. James Du Bois of Poughkeepsie, New York, a physician. In the Bahamas, Du Bois sired three sons, including Alfred, and a daughter of his slave mistress. [Lewis]

In 1890 Du Bois graduated cum laude from Harvard University and attended the University of Berlin in 1892. In 1896 Du Bois became the first Black person to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard University. After teaching at Wilberforce University in Ohio and the University of Pennsylvania, he went on to establish the first department of sociology in the United States at Atlanta University. [2]

Du Bois wrote many books including three major autobiographies. Among his works considered most significant were The Philadelphia Negro in 1896, The Souls of Black Folk in 1903, John Brown in 1909, Black Reconstruction in 1935, and Black Folk, Then and Now in 1939. His book, The Negro (published in 1915) influenced the work of pioneer Africanist scholars as Drusilla Dunjee Houston and William Leo Hansberry.[3][4]

In 1940 at Atlanta University, Du Bois founded Phylon magazine. In 1946, he wrote The World and Africa: An Inquiry Into the Part that Africa has Played in World History. In 1945 he helped organize the historic Fifth Pan-African Conference in Manchester, England. [5]

Du Bois was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha, the first intercollegiate Greek-letter fraternity established for African Americans.

While prominent white voices decried African American cultural, political and social relevance to American history and civic life, in his epic work, Reconstruction Du Bois documented how black people were the central figures in the American Civil War and Reconstruction. He demonstrated the ways Black emancipation—the crux of Reconstruction—promoted a radical restructuring of United States society, as well as how and why the country turned its back on human rights for African Americans in the aftermath of Reconstruction.[6] This theme was taken up later and expanded by Eric Foner and Leon F. Litwack, the two leading contemporary scholars of the Reconstruction era.

Civil rights activism

Du Bois was the most prominent intellectual leader and political activist on behalf of African Americans in the first half of the twentieth century. A contemporary of Booker T. Washington, the two carried on a dialogue about segregation and political disenfranchisement. Labeled the "father of Pan-Africanism", Du Bois believed that people of African descent should work together to battle prejudice and inequality.

In 1905, Du Bois helped to found the Niagara Movement with William Monroe Trotter but their alliance was short-lived as they had a dispute over whether or not white people should be included in the organization and in the struggle for Civil Rights. Du Bois felt that they should, and with a group of like-minded supporters, he helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

In 1910, he left his teaching post at Atlanta University to work as publications director at the NAACP full-time. He wrote weekly columns in many newspapers, including the Chicago Defender, the Pittsburgh Courier and the New York Amsterdam News, three African-American newspapers, and also the Hearst-owned San Francisco Chronicle.

At the NAACP, Du Bois worked as Editor-in-Chief of the NAACP's official publication, The Crisis, for twenty-five years. From this literary position, Du Bois commented freely and widely on current events. In an article published June 8, 1997 and titled "A New and Changed NAACP Magazine" by James Bock in The Baltimore Sun, the Crisis, under the stewardship of Du Bois, set the agenda for the fledgling NAACP.

With its circulation soaring from 1,000 in 1910 to more than 100,000 by 1920 with Du Bois as its editor, "It was a publishing phenomenon... putting it into a league with the Nation and The New Republic, said David Levering Lewis, the Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer of Du Bois.

Du Bois published Harlem Renaissance writers Langston Hughes and Jean Toomer, and, as a repository of black thought, the Crisis was initially a monopoly, Lewis observed. In 1913, Du Bois wrote The Star of Ethiopia, a historical pageant, to promote African-American history and civil rights.

The seminal debate between Booker T. Washington and Du Bois played out in the pages of the Crisis with Washington advocating an accommodational philosophy of self-help and vocational training for Southern blacks while Du Bois pressed for full educational opportunities.

Du Bois became increasingly estranged from Walter Francis White, the executive secretary of the NAACP, and began to question the organization's opposition to racial segregation at all costs. Du Bois thought that this policy, while generally sound, undermined those black institutions that did exist, which Du Bois thought should be defended and improved, rather than attacked as inferior. By the 1930s, Lewis said, the NAACP had become more institutional and Du Bois, increasingly radical, sometimes at odds with leaders such as Walter White and Roy Wilkins. In 1934, after writing two essays in the Crisis suggesting that black separatism could be a useful economic strategy, Du Bois left the magazine to return to teaching at Atlanta University.

Imperial Japan

Du Bois became impressed by the growing strength of Imperial Japan following the Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War. Du Bois saw the victory of Japan over Tsarist Russia as an example of "colored pride". According to Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer David Levering Lewis, Du Bois became a willing part of Japan's "Negro Propaganda Operations" run by Japanese academic and Imperial Agent Hikida Yasuichi.

After traveling to the United States to speak with University students at Howard University, Scripps College and Tuskegee University, Yasuichi became closely involved in shaping Du Bois's opinions of Imperial Japan. In 1936 Yasuichi and the Japanese Ambassador arranged a junket for Du Bois and a small group of fellow academics. The trip included stops in Japan, China, and the Soviet Union, although the Soviet leg was canceled because Du Bois' diplomatic contact, Karl Radek, had been swept up in Stalin's purges. While on the Chinese leg of the trip, Du Bois commented that the source of Chinese-Japanese enmity was China's "submission to white aggression and Japan's resistance", and he asked the Chinese people to welcome the Japanese as liberators. The effectiveness of the Japanese propaganda campaign was also seen when Du Bois joined a large group of African American academics that cited the Mukden Incident to justify occupation and annexation of southern Manchuria.

Joined Communist Party at Age 93

Du Bois was investigated by the FBI, who claimed in May of 1942 that "[h]is writing indicates him to be a socialist," and that he "has been called a Communist and at the same time criticized by the Communist Party."

Du Bois visited Communist China during the Great Leap Forward. Also, in the 16 March 1953 issue of The National Guardian, Du Bois wrote "Joseph Stalin was a great man; few other men of the 20th century approach his stature."

Du Bois was chairman of the Peace Information Center at the start of the Korean War. He was among the signers of the Stockholm Peace Pledge, which opposed the use of nuclear weapons. He was indicted in the United States under the Foreign Agents Registration Act and acquitted for lack of evidence. W.E.B. Du Bois became disillusioned with both black capitalism and racism in the United States. In 1959, Du Bois received the Lenin Peace Prize. In 1961, at the age of 93, he joined the Communist Party, USA and announced his membership in The New York Times.

Renunciation of U.S. citizenship

Du Bois was invited to Ghana in 1961 by President Kwame Nkrumah to direct the Encyclopedia Africana, a government production, and a long-held dream of his. When in 1963 he was refused a new U.S. passport because of his communism, he and his wife, Shirley Graham Du Bois, renounced their citizenship and became citizens of Ghana. Du Bois' health had declined in 1962, and on August 27, 1963 he died in Accra, Ghana at the age of ninety-five, one day before Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech.

In 1992, the United States honored W.E.B. Du Bois with his portrait on a postage stamp. On October 5, 1994, the main library at the University of Massachusetts Amherst was named after him.

Biographies

- David Levering Lewis, W.E.B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 1868-1919 (Owl Books 1994). Winner of the 1994 Pulitzer Prize for Biography[7]

- W.E.B. Du Bois: The Fight for Equality and the American Century 1919-1963 (Owl Books 2001). Covers the second half of the life of W.E.B. Du Bois, charting 44 years of the culture and politics of race in the United States. Winner of the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for Biography [8].

- Manning Marable, W.E.B Du Bois: Black Radical Democrat (Paradigm Publishers 2005).

Quotes

- "After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,--a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one's self through the eyes of others, of measuring one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness,--an American, a Negro; two warring souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder. The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife,--this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. ..."

- "One ever feels his twoness,--an American, a Negro; two warring souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder." - "Of Our Spiritual Strivings" in his book The Souls of Black Folk (1903)

- "I sit with Shakespeare, and he winces not. Across the color line I move arm and arm with Balzac and Dumas, where smiling men and welcoming women glide in gilded halls. From out of the caves of evening that swing between the strong-limbed Earth and the tracery of stars, I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and what soul I will, and they come all graciously with no scorn nor condescension. So, wed with Truth, I dwell above the veil."

- 'It is the obligation of all honorable men and women "to see that in the future competition of the races the survival of the fittest shall mean the triumph of the good, the beautiful, and the true: that we may be able to preserve for future civilization all that is really fine and noble and strong, and not continue to put a premium on greed and imprudence and cruelty."

- "The worker must work for the glory of his handiwork, not simply for pay; the thinker must think for truth, not for fame."

- "In my own country for nearly a century I have been nothing but a nigger." - to an audience in Beijing in 1959.

- "The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line."

- "I believe that there are human stocks with whom it is physically unwise to intermarry, but to think that these stocks are all colored or that there are no such white stocks is unscientific and false." [9]

- "The cause of war is preparation for war". [10]

- "One can hardly exaggerate the moral disaster of [religion]. We have to thank the Soviet Union for the courage to stop it."

- "The price of freedom is less than the cost of repression."

- "To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships."

Books by W.E.B Du Bois

- The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America: 1638–1870 PhD dissertation, 1896, (Harvard Historical Studies, Longmans, Green, and Co.: New York) Full Text

- The Study of the Negro Problems (1898)

- The Philadelphia Negro (1899)

- The Negro in Business (1899)

- The Evolution of Negro Leadership. The Dial, 31 (July 16, 1901).

- The Souls of Black Folk. 1999 [[[1903 in literature|1903]]]. ISBN 0-3939-7393-X.

- The Talented Tenth, second chapter of The Negro Problem, a collection of articles by African Americans (September 1903).

- Voice of the Negro II (September 1905)

- John Brown: A Biography (1909)

- Efforts for Social Betterment among Negro Americans (1909)

- Atlanta University's Studies of the Negro Problem (1897-1910)

- The Quest of the Silver Fleece 1911

- The Negro (1915)

- Darkwater (1920)

- The Gift of Black Folk (1924)

- Dark Princess: A Romance (1928)

- Africa, its Geography, People and Products (1930)

- Africa: Its Place in Modern History (1930)

- Black Reconstruction: An Essay toward a History of the Part which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880 (1935)

- What the Negro has Done for the United States and Texas (1936)

- Black Folk, Then and Now (1939)

- Dusk of Dawn: An Essay Toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept (1940)

- Color and Democracy: Colonies and Peace (1945)

- The Encyclopedia of the Negro(1946)

- The World and Africa (1946)

- Peace is Dangerous (1951)

- I take my stand for Peace (1951)

- In Battle for Peace (1952)

- The Black Flame: A Trilogy

- The Ordeal of Mansart (1957)

- Mansart Builds a School (1959)

- Africa in Battle Against Colonialism, Racialism, Imprialism (1960)

- Worlds of Color (1961)

- An ABC of Color: Selections from Over a Half Century of the Writings of W.E.B. Du Bois (1963)

- The World and Africa, An Inquiry into the Part Which Africa has Played in World History (1965)

- The Autobiography of W.E. Burghardt Du Bois (International publishers, 1968)

Articles by W.E.B. Du Bois

The American Negro Academy Occasional Papers, 1897, No. 2 "The Conservation Of Races" full text

Further Reading

- Eric J. Sundquist, ed.; The Oxford W.E.B. Du Bois Reader Oxford University Press. 1996

- The Oxford W.E.B. Du Bois Reader. Contributors: Eric J. Sundquist - editor. Publisher: Oxford University Press. Place of Publication: New York. Publication Year: 1996. Page Number: iii.

- Broderick Francis L. W. E. B. Du Bois: Negro Leader in a Time of Crisis Stanford University Press, 1959.

- Horne Gerald. Black and Red: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Afro-American Response to the Cold War, 1944-1963 State University of New York Press, 1986

- David Levering Lewis. W. E. B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 1868-1919 (1994), and vol 2: W. E. B. Du Bois: The Fight for Equality and the American Century, 1919-1963 (2001) Pulitzer prize

- Meier August. Negro Thought in America, 1880-1915: Racial Ideologies in the Age of Booker T. Washington University of Michigan Press, 1963.

- Rampersad Arnold. The Art and Imagination of W. E. B. Du Bois. Harvard University Press, 1976.

- Rudwick Elliott M. W. E. B. Du Bois: Propagandist of the Negro Protest. 1960

See also

- African American literature

- Marvel Cooke Secretary to DuBois when he was editor of The Crisis.

- Double Consciousness

- Drusilla Dunjee Houston, lecturer, syndicated columnist, author: Wonderful Ethiopians of the Ancient Cushite Empire, 1926.

References and external links

- W.E.B. Du Bois, The Autobiography of W. E. Burghardt Du Bois: A Soliloquy on Viewing My Life from the Last Decade of Its First Century. New York: International Publishers Co. Inc., 1968, pp. 438-440.

- Online articles by Du Bois

- "A Biographical Sketch of W.E.B. Du Bois" by Gerald C. Hynes

- Review materials for studying W.E.B. Du Bois

- FBI File of William E.B.Du Bois

- The W.E.B. Du Bois Virtual University

- Fighting Fire with Fire: African Americans and Hereditarian Thinking, 1900-1942

- The Talented Tenth

- W.E.B. DuBois and Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity

- 1868 births

- 1963 deaths

- African American intellectuals

- African American philosophers

- African American writers

- African Americans' rights activists

- African-American history

- Alpha Phi Alpha brothers

- American communists

- American historians

- American sociologists

- Spingarn Medal winners

- African Americans

- African American academics

- Humanitarians

- University of Massachusetts Amherst