History of Nova Scotia: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edit(s) by 99.227.209.125 identified as test/vandalism using STiki |

Hantsheroes (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 95: | Line 95: | ||

Nova Scotians fought in the [[Crimean War]]. The [[Welsford-Parker Monument]] in Halifax is the oldest war monument in Canada (1860) and the only Crimean War monument in North America. It commemorates the [[Siege of Sevastopol (1854–1855)]]. |

Nova Scotians fought in the [[Crimean War]]. The [[Welsford-Parker Monument]] in Halifax is the oldest war monument in Canada (1860) and the only Crimean War monument in North America. It commemorates the [[Siege of Sevastopol (1854–1855)]]. |

||

=== Indian Mutiny === |

|||

Nova Scotians also participated in the [[Indian Muntiny]]. Two of the most famous were [[William Hall (VC)]] and Sir [[John Eardley Inglis]], both of whom participated in the [[Siege of Lucknow]]. The [[78th (Highlanders) Regiment of Foot]] were famous for their involvement with the siege and were later posted to [[Citadel Hill (Fort George)]]. |

|||

=== Responsible government === |

=== Responsible government === |

||

Revision as of 08:20, 26 September 2012

Nova Scotia (also known as Mi'kma'ki and Acadia) is a Canadian province located in Canada's Maritimes. The region was initially occupied by Mi'kmaq. During the first 150 years of European settlement, the colony was primarily made up of Catholic Acadians and Mi'kmaq. This time period involved the French and Indian Wars between New England (former British territory) and New France (former French territory) as well as two local wars - Father Rale's War and Father Le Loutre's War before Britain defeated France in North America. Throughout these wars, Nova Scotia was the site of numerous battles, raids and skirmishes. The Conquest of Acadia happened in 1710. Just prior to the last colonial war, the French and Indian War. The capital was moved from Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia to the newly founded Halifax, Nova Scotia. After the colonial wars, New England Planters and Foreign Protestants settled Nova Scotia. After the American Revolution, the colony was settled by Loyalists. During the nineteenth century, Nova Scotia became self-governing in 1848 and joined the Canadian Confederation in 1867.

The colonial history of Nova Scotia includes the present-day Canadian Maritime provinces and northern Maine (see Sunbury County, Nova Scotia), all of which were at one time part of Nova Scotia. In 1763 Cape Breton Island and St. John's Island (what is now Prince Edward Island) became part of Nova Scotia. In 1769, St. John's Island became a separate colony. Nova Scotia included present-day New Brunswick until that province was established in 1784.[1]

Mi'kmaq

The oldest evidence of humans in Nova Scotia indicates the Paleo-Indians were the first, approximately 11,000 years ago. Natives are believed to have been present in the area between 11,000 and 5,000 years ago. Mi'kmaq, the First Nations of the province and region, are their direct descendants.

The Mi'kmaq (previously spelled Micmac in English texts) are a First Nations people, indigenous to the Maritime Provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula Quebec and northeastern New England. Míkmaw is the singular form of Mí'kmaq.

In 1616 Father Biard believed the Mi'kmaq population to be in excess of 3,000. However, he remarked that, because of European diseases, including smallpox and alcoholism, there had been large population losses in the previous century.

The Mi'kmaq were originally allies with other nearby Algonquian nations including the Abenaki, forming the seven nation Wabanaki Confederacy, pronounced Template:IPA-alg; this was later expanded to eight with the ceremonial addition of Great Britain at the time of the 1749 treaty. At the time of contact with the French (late 16th century) they were expanding from their Maritime base westward along the Gaspé Peninsula /St. Lawrence River at the expense of Iroquioian Mohawk tribes, hence the Mi'kmaq name for this peninsula, Gespedeg ("last-acquired"). They were amenable to limited French settlement in their midst. Between the loss of control of Acadia by France in the early 18th century and the deportation of the Acadians in the mid-eighteenth century an uneasy stalemate existed between the Mi’kmaq and English. With the complete loss by France during the Seven Years' War of its North American territories, the Mi’kmaq lost their primary ally. The Mi’kmaq continued to suffer a population collapse and with the influx of Planters in the 1760s and Loyalists in the 1780s, soon found themselves overwhelmed. Later on the Mi'kmaq also settled Newfoundland as the unrelated Beothuk tribe became extinct.

Seventeenth century

Port Royal established

The first European settlement in Nova Scotia was established in 1605. The French, led by Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Monts established the first capital for the colony Acadia at Port Royal.[2] Other than a few trading posts around the province, for the next seventy-five years, Port Royal was virtually the only European settlement in Nova Scotia. Port Royal (later renamed Annapolis Royal) remained the capital of Acadia and later Nova Scotia for almost 150 years, prior to the founding of Halifax in 1749.

Approximately seventy-five years after Port Royal was founded, Acadians migrated from the capital and established what would become the other major Acadian settlements before the Expulsion of the Acadians: Grand Pré, Chignecto, Cobequid and Pisiguit.

Until the Conquest of Acadia, the English made six attempts to conquer Acadia by defeating the capital. They finally defeated the French in the Siege of Port Royal in 1710. Over the following fifty years, the French and their allies made six unsuccessful military attempts to regain the capital.[3]

Scottish Colony

From 1629-1632, Nova Scotia briefly became a Scottish colony. Sir William Alexander of Menstrie Castle, Scotland claimed mainland Nova Scotia and settled at Port Royal, while Ochiltree claimed Ile Royale (present-day Cape Breton Island) and settled at Baleine, Nova Scotia. There were three battles between the Scottish and the French: the Raid on St. John (1632), the Siege of Baleine (1629) as well as Siege of Cap de Sable (present-day Port La Tour, Nova Scotia) (1630). Nova Scotia was returned to France through a treaty.[4]

The French quickly defeated the Scottish at Baleine and established settlements on Ile Royale at present day Englishtown (1629) and St. Peter's (1630). These two settlements remained the only settlements on the island until they were abandoned by Nicolas Denys in 1659. Ile Royale then remained vacant for more than fifty years until the communities were re-established when Louisbourg was established in 1713.

Acadian Civil War

Acadia was plunged into what some historians have described as a civil war in Acadia (1640–1645). The war was between Port Royal, where Governor of Acadia Charles de Menou d'Aulnay de Charnisay was stationed, and present-day Saint John, New Brunswick, where Governor of Acadia. Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour was stationed.[5]

In the war, there were four major battles. la Tour attacked d'Aulnay at Port Royal in 1640.[6] In response to the attack, D'Aulnay sailed out of Port Royal to establish a five month blockade of La Tour's fort at Saint John, which La Tour eventually defeated (1643). La Tour attacked d'Aulnay again at Port Royal in 1643. d'Aulnay and Port Royal ultimately won the war against La Tour with the 1645 siege of Saint John.[7] After d'Aulnay died (1650), La Tour re-established himself in Acadia.

Eighteenth century

The Colonial Wars

There were six colonial wars that took place in Nova Scotia over a seventy-four year period (see the French and Indian Wars as well as Father Rale's War and Father Le Loutre's War). These wars were fought between New England and New France and their respective native allies before the British defeated the French in North America (1763). During these wars, Acadians, Mi'kmaq and Maliseet from the region fought to protect the border of Acadia from New England, which New France defined as the Kennebec River in southern Maine.[8] The wars also involved attempting to prevent the New Englanders from taking the capital of Acadia, Port Royal (See Queen Anne's War), establishing themselves at Canso (See Father Rale's War) and establishing Halifax (See Father Le Loutre's War). The seventy-five year period of war ended with the Burial of the Hatchet Ceremony between the British and the Mi'kmaq (1761).

New England Planters

After Britain won the French and Indian War, between 1759 and 1768, about 8,000 New England Planters responded to Governor Charles Lawrence's request for settlers from the New England colonies.

Government changes

The colony's jurisdiction changed during this time. Nova Scotia was granted a supreme court in 1754 with the appointment of Jonathan Belcher and a Legislative Assembly in 1758. In 1763 Cape Breton Island became part of Nova Scotia. In 1769, St. John's Island (now Prince Edward Island) became a separate colony. The county of Sunbury was created in 1765, and included all of the territory of current day New Brunswick and eastern Maine as far as the Penobscot River. In 1784, the western, mainland portion of the colony was separated and became the province of New Brunswick. Maine became part of the newly independent American state of Massachusetts, but the international boundary was vague. Cape Breton became a separate colony in 1784; it was returned to Nova Scotia in 1820.

Confronted with a large Yankee element sympathetic to the American revolution, Nova Scotian politicians in 1774-75 adopted a policy of enlightened moderation and humanism. Governing a marginal colony that received little attention from London, the royal governor, Francis Legge (1772 to 1776) battled the popularly elected assembly for control of the policies regarding trade, commerce, and taxation.[9] Desserud shows that John Day, elected to the assembly in 1774, called for Montesquieu-type fundamental reforms that would balance political power among the three branches of government. Day argued that taxes should be assessed according to actual wealth, and to discourage patronage there should be term limits for all officials. He thought members of the Executive Council should own at least ₤1000 of property to connect their personal interest in the welfare of the colony as a whole. He wanted the dismissal of judges who misused their offices. There reforms were not as yet enacted, but they suggest that politicians in Nova Scotia were aware of the demands being made by Americans, and hoped their moderate proposals would reduce possible tensions with the British government.[10]

American Revolution

The American Revolution (1776–1783) had a significant impact on shaping Nova Scotia. At the beginning, there was ambivalence in Nova Scotia, "the 14th American Colony" as some called it, over whether the colony should join the Americans in the war against Britain. Rebellions flared at the Battle of Fort Cumberland, the Siege of Saint John (1777), the Maugerville Rebellion in 1776 and the Battle at Miramichi in 1779. However the Nova Scotia government in Halifax was controlled by an Anglo-European mercantile elite for whom loyalty was more profitable than rebellion. Facing attacks which forced choices of loyalty, rebellion or neutrality, settlers outside Halifax experienced a religious revival that expressed some of their anxieties.[11] Throughout the war, American privateers devastated the maritime economy by raiding many of the coastal communities. In addition to capturing 225 vessels either leaving or arriving at Nova Scotia ports,[12] American privateers made regular land raids, attacking Lunenburg, Annapolis Royal, Canso and Liverpool. American Privateers also repeatedly raided Canso, Nova Scotia in 1775 and 1779, destroying the fisheries, which were worth £50,000 a year to Britain.[13] These American raids alienated many sympathetic or neutral Nova Scotians into supporting the British. By the end of the war a number of Nova Scotian privateers were outfitted to attack American shipping.[14]

.

To guard against repeated American privateer attacks, the 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants) was garrisoned at forts around the Atlantic Canada to strengthen the small and ill-equipped militia companies of the colony. Fort Edward (Nova Scotia) in Windsor, Nova Scotia was the Regiment's headquarters to prevent a possible American land assault on Halifax from the Bay of Fundy. There was an American attack on Nova Scotia by land, the Battle of Fort Cumberland followed by the Siege of Saint John (1777)

The British naval squadron based at Halifax was successful in deterring any American invasion, blocking American support for Nova Scotia rebels and launched some attacks on New England, such as the Battle of Machias (1777). However the Royal Navy was unable to establish naval supremacy. While many American privateers were captured in battles such as the Naval battle off Halifax, many more continued attacks on shipping and settlements until the final months of the war. The Royal Navy struggled to maintain British supply lines, defending convoys from American and in 1781, after the Franco-American alliance against Great Britain, French attacks such as a fiercely fought convoy battle, the a naval engagement with a French fleet at Sydney, Nova Scotia, near Spanish River, Cape Breton.[15]

Loyalists

After the British were defeated in the Thirteen Colonies, some former Nova Scotian territory in Maine entered the control of the newly independent American state of Massachusetts. British troops from Nova Scotia helped evacuate approximately 30,000 United Empire Loyalists (American Tories), who settled in Nova Scotia, with land grants by the Crown as some compensation for their losses. Of these, 14,000 went to present-day New Brunswick and in response the mainland portion of the Nova Scotia colony was separated and became the province of New Brunswickwith Sir Thomas Carleton the first governor on August 16, 1784.[16] Loyalist settlements also led Cape Breton Island became a separate colony in 1784, only to be returned to Nova Scotia in 1820.

The Loyalists exodus created new communities across Nova Scotia, including Shelburne, which briefly one of the larger British settlements in North America, and infused the province with additional capital and skills. The Loyalist migration also caused political tensions between Loyalist leaders and the leaders of the existing New England Planters settlement. Some Loyalist leaders felt that the elected leaders in Nova Scotia represented a Yankee population which had been sympathetic to the American Revolutionary movement, and which disparaged the intensely anti-American, anti-republican attitudes of the Loyalists. "They [the loyalists]," Colonel Thomas Dundas wrote in 1786, "have experienced every possible injury from the old inhabitants of Nova Scotia, who are even more disaffected towards the British Government than any of the new States ever were. This makes me much doubt their remaining long dependent."[17]

The Loyalist influx also created pressure for settlement land which pushed Nova Scotia's Mi'kmaq People to the margins as Loyalist land grants encroached on ill-defined native lands. Approximately 3,000 members of the Loyalist migration were Black Loyalists who founded the largest free Black settlement in North American at Birchtown, near Shelburne. However unfair treatment and harsh conditions cause about one-third of the Black Loyalists to combine forces with British abolitionists and the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor to resettle in Sierra Leone. In 1792, Black Loyalists from Nova Scotia they founded Freetown and became known in Africa as the Nova Scotian Settlers.[18]

Large numbers of Gaelic-speaking Highland Scots emigrated to Cape Breton and the western part of the mainland during the late 18th century and 19th century. In 1812 Sir Hector Maclean (the 7th Baronet of Morvern and 23rd Chief of the Clan Maclean) emigrated to Pictou from Glensanda and Kingairloch in Scotland bringing along almost the entire population of 500.[19]

Nineteenth century

Renewed Wars with France

The French Revolutionary and later Napoleonic Wars at first created confusion and hardship as the fishery was disrupted and Nova Scotia's West Indies trade suffered severe French attacks. However, military spending in the strategic colony gradually led to increasing prosperity. Many Nova Scotian merchants outfitted their own privateers to attack French and Spanish shipping in the West Indies. The maturing colony built new roads and lighthouses and in 1801 established a lifesaving station on Sable Island to deal with the many international shipwrecks on the island.

War of 1812

During the War of 1812 with the United States, Nova Scotia became an even larger military base for the British as the centre for the British Royal Navy's blockade and naval raids on the United States. The colony also contributed to the war effort by purchasing or building various privateer ships to seize 250 American vessels.[20] The colony's privateers were led by the town of Liverpool, Nova Scotia, notably by the schooner Liverpool Packet which captured over fifty ships in the war - the most of any privateer in Canada.[21] The Sir John Sherbrooke (Halifax), jointly owned between Liverpool and Halifax was also very successful during the war, being the largest privateer from British North America. Other communities also joined the privateer campaign, including Annapolis Royal, Windsor, and in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, three members of the town of purchased a privateer schooner and named it Lunenburg on August 8, 1814.[22]The Nova Scotian privateer vessel captured seven American vessels.

Perhaps the most dramatic moment in the war for Nova Scotia was the HMS Shannon's led the captured American Frigate USS Chesapeake into Halifax Harbour (1813). The Captain of the Shannon was injured and Nova Scotian Provo Wallis took command of the ship to escort the Chesapeake to Halifax. Many of the prisoners were kept at Deadman's Island, Halifax.[21] At the same time, there was the HMS Hogue's traumatic capture of the American Privateer Young Teazer off Chester, Nova Scotia.

On September 3, 1814 a British fleet from Halifax, Nova Scotia began to lay siege to Maine to re-establish British title to Maine east of the Penobscot River, an area the British had renamed "New Ireland". Carving off "New Ireland" from New England had been a goal of the British government and settlers of Nova Scotia ("New Scotland") since the American Revolution.[23] The British expedition involved 8 war-ships and 10 transports (carrying 3,500 British regulars) that were under the overall command of Sir John Coape Sherbrooke, then Lt. Gov. of Nova Scotia.[24] On July 3, 1814, the expedition captured the coastal town of Castine, Maine and then went on to raid Belfast, Machias, Eastport, Hampden and Bangor(See Battle of Hampden). After the war, Maine was returned to America through the Treaty of Ghent. The British returned to Halifax and, with the spoils of war they had taken from Maine, they built Dalhousie University (established 1818).[25]

The Black Refugees from the War of 1812 were African American slaves who fought for the British and were relocated to Nova Scotia. The Black Refugees were the second group of African Americans, after the Black Loyalists, to defect to the British side and be relocated to Nova Scotia.

There was also migration out of the colony because of the hardships immigrants faced. Reverend Norman McLeod led a large group of approximately 800 Scottish residents from the St. Anns, Nova Scotia to Waipu, New Zealand, during the 1850s.

Workers

Working conditions in the Halifax Naval Yard during the 1775-1820 era included officials who took bribes from workers and widespread nepotism. The laborers endured poor working conditions and limited personal freedoms. However, the laborers were willing to remain there for many years because wages were high and more steady than any alternative. Unlike almost any other jobs the yards paid disability benefits for men injured at work and gave retirement pensions to those who spent their career in the yards.[26]

Nova Scotia had one of the first labour organizations in what became Canada. By 1799 workers set up a Carpenters' Society at Halifax, and soon there were attempts at organization by other craftsmen and tradesmen. Businessmen complained, and in 1816 Nova Scotia passed an act against trade unions, the preamble of which declared that great numbers of master tradesmen, journeymen, and workmen in the town of Halifax and other parts of the province had, by unlawful meetings and combinations, endeavored to regulate the rate of wages and effectuate other illegal aims. Unions remained illegal until 1851.[27]

Crimean War

Nova Scotians fought in the Crimean War. The Welsford-Parker Monument in Halifax is the oldest war monument in Canada (1860) and the only Crimean War monument in North America. It commemorates the Siege of Sevastopol (1854–1855).

Indian Mutiny

Nova Scotians also participated in the Indian Muntiny. Two of the most famous were William Hall (VC) and Sir John Eardley Inglis, both of whom participated in the Siege of Lucknow. The 78th (Highlanders) Regiment of Foot were famous for their involvement with the siege and were later posted to Citadel Hill (Fort George).

Responsible government

Nova Scotia was the first colony in British North America and in the British Empire to achieve responsible government in January–February 1848 and become self-governing through the efforts of Joseph Howe.[28] (In 1758, Nova Scotia also became the first British colony to establish representative government, commemorated in 1908 by erecting the Dingle Tower.)

-

Nova Scotia postage stamp (1851-1857). Printed in England. Also used in New Brunswick.

-

Nova Scotia stamp (issued 1860)

American Civil War

Over 200 Nova Scotians have been identified as fighting in the American Civil War (1861–1865). Most joined Maine or Massachusetts infantry regiments, but one in ten served the Confederacy (South). The total probably reached into two thousand as many young men had migrated to the U.S. before 1860. Pacifism, neutrality, anti-Americanism, and anti-Yankee sentiments all operated to keep the numbers down, but on the other hand there were strong cash incentives to join the well-paid Northern army and the long tradition of emigrating out of Nova Scotia, combined with a zest for adventure, attracted many young men.[29]

The British Empire (including Nova Scotia) declared neutrality, and Nova Scotia prospered greatly from trade with the North. There were no attempts to trade with the South. Nova Scotia was the site of two minor international incidents during the war: the Chesapeake Affair and the escape from Halifax Harbour of the CSS Tallahassee, aided by Confederate sympathizers.[30]

The war left many fearful that the North might attempt to annex British North America, particularly after the Fenian raids began. In response, volunteer regiments were raised across Nova Scotia. One of the main reasons why Britain sanctioned the creation of Canada (1867) was to avoid another possible conflict with America and to leave the defence of Nova Scotia to a Canadian Government.[31]

Anti-Confederation campaign

The British North America Act, by which Nova Scotia became part of the Dominion of Canada, went into effect on July 1, 1867. Premier Charles Tupper had worked energetically to bring about the union. But it was controversial because localism, Protestant fears of Catholics and distrust of Canadians generally, and worries about losing free trade with America, were all intensified by the refusal of Tupper to consult Nova Scotia's voters on the subject. A movement for withdrawal from Canada developed, led by Joseph Howe. Howe's Anti-Confederation Party swept the next election, on September 18, 1867, winning 18 out of 19 federal seats, and 36 out of 38 seats in the provincial legislature. A motion passed by the Nova Scotia House of Assembly in 1868 refusing to recognise the legitimacy of Confederation has never been rescinded. With the great Hants County bi-election of 1869, Howe was successful in turning the province away from appealing confederation to simply seeking "better terms" within it.[28] Despite its temporary popularity, Howe's movement failed in its goal to withdraw from Canada because London was determined the union go forward. Howe did succeed in getting better financial terms for the province, and gained a national office for himself.[32]

Long-term adverse factors came into play. In 1865 came the end of the American Civil War and all the extra business it had generated. In 1866 came the end of Canadian-American Reciprocity Treaty, which led to higher and damaging American tariffs on goods imported from Nova Scotia. In the long run the transition at sea from wood-wind-water sailing to steel steamships undercut the advantages Nova Scotia had enjoyed before 1867. Many residents for decades grumbled that Confederation had slowed the economic progress of the province and it lagged other parts of Canada. Repeal, as anti-confederation became known, would rear its head again in the 1880s, and transform into the Maritime Rights Movement in the 1920s. Some Nova Scotia flags flew at half mast on Dominion Day as late as that time.

Economic growth

Most people were farmers and agriculture dominated the economy, despite all the attention given to ships. The rural situation peaked in 1891 in terms of total rural population, farmland, grain production, cattle production, and number of farms, then fell steadily into the 21st century. Apples and dairy products resisted the downward trend in the 20th century.[33]

The pattern of Nova Scotia's trade and tariffs between 1830 and 1866 suggests that the colony was already moving toward free trade before the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 with the U.S. took effect. The treaty produced modest additional direct gains. The Reciprocity Treaty complemented the earlier movement toward free trade and stimulated the export of commodities sold primarily to the United States, especially coal.[34]

Halifax was the home of Samuel Cunard. With his father, Abraham, a master ship's carpenter, he founded the A. Cunard & Co. cargo shipping company and later the Cunard Line, a pride of the British Empire. Samuel parlayed his father's modest waterfront properties into a succession of businesses that revolutionized transatlantic shipping and passenger travel with the introduction of steam and steel. Cunard was a booster who was active in philanthropy and helped found the Chamber of Commerce, where he found business partners for his ventures in banking, mining, and other businesses. In the process he became one of the largest landholders in the Maritime Provinces.[35]

John Fitzwilliam Stairs (1848–1904), scion of the powerful Stairs family, enlarged the family's multiple businesses by merging the cordage firms and sugar refineries and then creating the steel industry in the province. In order to develop new regional sources of capital, Stairs became an innovator in building legal and regulatory frameworks for these new forms of financial structure. Frost contrasts Stairs's success in promoting regional development with the obstacles that he had encountered in promoting regional interests, particularly at the federal level. The family finally sold its businesses in 1971, after 160 years.[36][37]

After Confederation, boosters of Halifax expected federal help to make the city's natural harbor Canada's official winter port and a gateway for trade with Europe. Halifax's advantages included its location just off the Great Circle route made it the closest to Europe of any mainland North American port. But the new Intercolonial Railway (ICR) took an indirect, southerly route for military and political reasons, and the national government made little effort to promote Halifax as Canada's winter port. Ignoring appeals to nationalism and the ICR's own attempts to promote traffic to Halifax, most Canadian exporters sent their wares by train though Boston or Portland. No one was interested in financing the large-scale port facilities Halifax lacked. It took the First World War to at last boost Halifax's harbor into prominence on the North Atlantic.[38]

Unionization, legal after 1851, was based on skilled crafts except in the coal mines and steel plants, where unskilled men could also join. There has been an increase in industrial unionism with the expansion of industry. International unionism with a strong American influence became important, as international unions began in 1869, when a local of the International Typographical Union was chartered in Halifax. In 1870 the woodworking trades started their union. Different unions banded together to support strike action, as seen in the organization of the Amalgamated Trade Unions of Halifax in 1889, which was succeeded by the Halifax District Trades and Labour Council in 1898. By the end of the 19th century there were more than 70 local unions in the province.[39][40]

Golden age of sail

Nova Scotia became a world leader in both building and owning wooden sailing ships in the second half of the century. Nova Scotia produced internationally recognized ship builders Donald McKay and William Dawson Lawrence. Notable ships included the barque Stag, a clipper renowned for speed and the ship William D. Lawrence, the largest wooden ship ever built in Canada. The fame Nova Scotia achieved from sailors was assured when Joshua Slocum became the first man to sail single-handedly around the world (1895). This international attention continued into the following century with the many racing victories of the Bluenose schooner.

The population grew steadily from 277,000 in 1851 to 388,000 in 1871, mostly from natural increase since immigration was slight. The era has been called a golden age, but that was a myth created in the 1930s to lure tourists to a romantic era of tall ships and antiques.[41] Recent historians using census data have shown that is a fallacy. In 1851-1871 there was an overall increase in per capita wealth holding. However most of the gains went to the urban elite class, especially businessmen and financiers living in Halifax. The wealth held by the top 10% rose considerably over the two decades, but there was little improvement in the wealth levels in rural areas, which comprised the great majority of the population.[42] Likewise Gwyn reports that gentlemen, merchants, bankers, colliery owners, shipowners, shipbuilders, and master mariners flourished. However the great majority of families were headed by farmers, fishermen, craftsmen and laborers. Most of them-and many widows as well—lived in poverty. Out migration became an increasingly necessary option.[43][44] Thus the era was indeed a golden age but only for a small but powerful and highly visible elite.

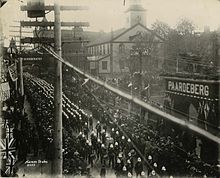

North West Rebellion

The Halifax Provisional Battalion was a military unit from Nova Scotia, Canada, which was sent to fight in the North-West Rebellion in 1885. The battalion was under command of Lieut.-Colonel James J. Bremner and consisted of 168 non-commissioned officers and men of the The Princess Louise Fusiliers, 100 of the 63rd Battalion Rifles, and 84 of the Halifax Garrison Artillery, with 32 officers. The battalion left Halifax under orders for the North-West on Saturday, April 11, 1885, and they stayed for almost three months.[45]

Twentieth century

Heavy industry

The Nova Scotia Steel and Coal Company (known as Scotia) became a vertically-integrated industrial giant. It grew rapidly and made handsome profits from exports of coal, pig iron and steel products to Canadian and international markets. At first its convenient tidewater location and control over all steps of production boosted growth, as it grew through mergers and acquisitions. However the long term negative factors included fragmentation, limited Maritime region markets, rising costs, low quality raw materials, and the lack of external economies.[46] When Scotia (now called DOSCO--Dominion Steel and Coal Corporation) finally closed in the 1960s it was a blow to numerous towns that had counted on its well paid jobs and the political activism of its workers, such as Florence, Reserve Mines, Sydney Mines, Trenton, and New Glasgow.[47]

Rural decline and political response

Rural areas steadily lost population, especially the eastern counties. Liberal premiers George Henry Murray (1896–1923) and Ernest H. Armstrong (1923–25) implemented programs to improve rural life and modernize agricultural industry. They secured federal assistance through loans and grants for agriculture, roads, and immigration. Murray was criticized for being too cautious in his reforms, while Armstrong, even with a Liberal federal government behind him, was unable to keep the assistance flowing. The situation only worsened with the post-war downturn which brought the United Farmers Party to power in 1920 in the hardest hit areas of eastern Nova Scotia. The Liberals' failure to stem the decline of the area brought their defeat in 1925 by "rejuvenated" Conservatives who capitalized on Armstrong's weakness.[48]

Second Boer War

During the Second Boer War (1899–1902), the First Contingent was composed of seven Companies from across Canada. The Nova Scotia Company (H) consisted of 125 men. (The total First Contingent was a total force of 1,019. Eventually over 8600 Canadians served.) The mobilization of the Contingent took place at Quebec. On October 30, 1899, the ship Sardinian sailed the troops for four weeks to Cape Town. The Boer War marked the first occasion in which large contingents of Nova Scotian troops served abroad (individual Nova Scotians had served in the Crimean War). The Battle of Paardeberg in February 1900 represented the second time Canadian soldiers saw battle abroad (the first being the Canadian involvement in the Nile Expedition).[49] Canadians also saw action at the Battle of Faber's Put on May 30, 1900.[50] On November 7, 1900, the Royal Canadian Dragoons engaged the Boers in the Battle of Leliefontein, where they saved British guns from capture during a retreat from the banks of the Komati River.[51] Approximately 267 Canadians died in the War. 89 men were killed in action, 135 died of disease, and the remainder died of accident or injury. 252 were wounded.

Of all the Canadians who died during the war, the most famous was the young Lt. Harold Lothrop Borden of Canning, Nova Scotia. Harold Borden's father was Sir Frederick W. Borden, Canada's Minister of Militia who was a strong proponent of Canadian participation in the war.[52] Another famous Nova Scotian casualty of the war was Charles Carroll Wood, son of the renoun Confederate naval captain John Taylor Wood and the first Canadian to die in the war.[53]

First World War

During World War I, Halifax became a major international port and naval facility. The harbour became a major shipment point for war supplies, troop ships to Europe from Canada and the United States and hospital ships returning the wounded. These factors drove a major military, industrial and residential expansion of the city.[54]

On Thursday, December 6, 1917, when the city of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, was devastated by the huge detonation of a French cargo ship, fully loaded with wartime explosives, that had accidentally collided with a Norwegian ship in "The Narrows" section of the Halifax Harbour. Approximately 2,000 people (mostly Canadians) were killed by debris, fires, or collapsed buildings, and it is estimated that over 9,000 people were injured.[55] This is still the world's largest man-made accidental explosion.[56]

1930s

Nova Scotia was hard hit by the worldwide Great Depression that began in 1929 as demand plunged for coal and steel, and the prices of fish and lumber plummeted. Prosperity returned in World War II, especially as Halifax again became a major staging point for convoys to Britain. Liberal premier Angus L. Macdonald dominated the political scene as premier (1933–40 and 1945–54). Macdonald dealt with the mass unemployment of the 1930s by putting the jobless to work on highway projects. He felt direct government relief payments would weaken moral character, undermine self-respect and discourage personal initiative.[57] However, he also faced the reality that his financially strapped government could not afford to participate fully in federal relief programs that required matching contributions from the provinces.[58]

The Antigonish Movement emerged offering a "middle way" to helping people distressed hit by the depression through cooperative ventures under popular control. It was a Catholic operation started by Reverend Moses Coady of St Francis Xavier University in 1928. He sought a Church-approved alternative to socialism or capitalism. The cooperatives were organized at the grass roots and brought together fishermen, farmers, miners and factory workers, especially in the eastern districts. They set up local fish processing plants, credit unions, housing co-ops, and co-operative stores. Ownership and control was in the hands of the people directly involved It declined after 1950.[59]

Labour unions

The Provincial Workmen's Association began in 1879 as a miners' union; in 1898, faced by a challenge from the Knights of Labor, it sought to embrace unions in all the industries of the province. The first local union of the United Mine Workers was established in 1908. After a struggle for control of the labour movement among the miners, the Provincial Workmen's Association was dissolved in 1917, and by 1919 the United Mine Workers took control of the coal miners. Success was due to the aggressive leadership of J. B. McLachlan (1869–1937), who left the coal mines of Scotland for Canada in 1902, became a Communist (1922 to 1936) and promoted a strong union and a tradition of independent labour politics. McLachlan’s battles with the American UMWA leadership, particularly the dictatorial John L. Lewis, demonstrated his commitment to democratic unionism for the miners and a fighting union, but Lewis won and outsted McLachlan from power.[60]

Women played an important, though quiet, role in support of the union movement in coal towns during the troubled 1920s and 1930s. They never worked for the mines but provided psychological support especially during strikes when the pay packets did not arrive. They were the family financiers and encouraged other wives who otherwise might have coaxed their menfolk to accept company terms. Women's labor leagues organized a variety of social, educational, and fund-raising functions. Women also violently confronted "scabs", policemen, and soldiers. They had to stretch the food dollar and show inventiveness in clothing their families.[61]

World War II

During World War II, thousands of Nova Scotians went overseas. One Nova Scotian, Mona Louise Parsons, joined the Dutch resistance and was eventually captured and imprisoned by the Nazis for almost four years.

Since 1945

After the war Macdonald initiated large-scale spending programs for such services as health, education, labor union protection measures, and pensions.

Conservative Robert L. Stanfield served as premier during 1956-67. The pragmatic Stanfield, though in favor of some government intervention in economic affairs, was cautious about social policy and was unwilling to promote the welfare state. Nevertheless, new hospitals were built, funded by a sales tax. After 1960 there was increased emphasis on provincial assistance for local municipalities in health and education, with finances for university expansion. Generally, Stanfield, though a conservative, took a positive view of the state's role in helping citizens overcome poverty, ill-health, and discrimination and accepted the need to raise taxes to pay for such services.[62]

See also

- Nova Scotia Federation of Labour

- List of National Historic Sites of Canada in Nova Scotia

- History of Acadia

- Military history of Nova Scotia

References

- ^ In 1765, the county of Sunbury was created, and included the territory of present-day New Brunswick and eastern Maine as far as the Penobscot River.

- ^ Also, that same year, French fishermen established a settlement at Canso.

- ^ Brenda Dunn. A History of Port Royal, Annapolis Royal: 1605-1800. Nimbus Publishing, 2004

- ^ Nicholls, Andrew. A Fleeting Empire: Early Stuart Britain and the Merchant Adventures to Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press. 2010.

- ^ M. A. MacDonald, Fortune & La Tour: The civil war in Acadia, Toronto: Methuen. 1983

- ^ Brenda Dunn, p. 19

- ^ Brenda Dunn. A History of Port Royal, Annapolis Royal: 1605-1800. Nimbus Publishing, 2004. p. 20

- ^ William Williamson. The history of the state of Maine. Vol. 2. 1832. p. 27

- ^ John Brebner, The Neutral Yankees of Nova Scotia: A Marginal Colony During the Revolutionary Years (1937)

- ^ Donald A. Desserud, "An Outpost's Response: The Language and Politics of Moderation in Eighteenth-century Nova Scotia," American Review of Canadian Studies 1999 29(3): 379-405.

- ^ Barry Cahill, "The Treason of the Merchants: Dissent and Repression in Halifax in the Era of the American Revolution," Acadiensis 1996 26(1): 52-70; G. Stewart, and G. Rawlyk, A People Highly Favoured of God: The Nova Scotia Yankees and the American Revolution (1972); Maurice Armstrong, "Neutrality and Religion in Revolutionary Nova Scotia," The New England Quarterly v19, no. 1 (1946): 50-62 in JSTOR

- ^ Julian Gwyn. Frigates and Foremasts. University of British Columbia. 2003. p. 56

- ^ Lieutenant Governor Sir Richard Hughes stated in a dispatch to Lord Germaine that "rebel cruisers" made the attack.

- ^ Roger Marsters (2004). Bold Privateers: Terror, Plunder and Profit on Canada's Atlantic Coast, p. 87–89.

- ^ Thomas B. Akins. (1895) History of Halifax. Dartmouth: Brook House Press.p. 82

- ^ Neil MacKinnon, This Unfriendly Soil: The Loyalist Experience in Nova Scotia, 1783-1791 (1989)

- ^ S.D. Clark, Movements of Political Protest in Canada, 1640–1840, (1959), pp. 150-51

- ^ Simon Schama, Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves and the American Revolution, Viking Canada (2005) p. 11

- ^ Donald Campbell and R. A. MacLean, Beyond the Atlantic roar: a study of the Nova Scotia Scots (1974) p. 3

- ^ John Boileau. Half-hearted Enemies: Nova Scotia, New England and the War of 1812. Halifax: Formac Publishing. 2005. p.53

- ^ a b John Boileau. 2005. Half-hearted Enemies: Nova Scotia: New England and the War of 1812. Formac Press

- ^ C.H.J.Snider, Under the Red Jack: privateers of the Maritime Provinces of Canada in the War of 1812 (London: Martin Hopkinson & Co. Ltd, 1928), 225-258 (see http://www.1812privateers.org/Ca/canada.htm#LG)

- ^ Seymour, p. 10

- ^ Tom Seymour, Tom Seymour's Maine: A Maine Anthology (2003), pp. 10-17

- ^ D.C. Harvey, "The Halifax–Castine expedition," Dalhousie Review, 18 (1938–39): 207–13.

- ^ Julian Gwyn, "the Culture of Work in the Halifax Naval Yard Before 1820." Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society 1999 2: 118-144.

- ^ Buckner and Reid, The Atlantic region to Confederation: a history (1995) p. 338

- ^ a b Beck, J. Murray. (1983) Joseph Howe: The Briton Becomes Canadian 1848–1873. (v.2). Kingston & Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-0388-9

- ^ Greg Marquis, "Mercenaries or Killer Angels? Nova Scotians in the American Civil War," Collections of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society, 1995, Vol. 44, pp 83-94

- ^ Greg Marquis, In Armageddon’s Shadow: The Civil War and Canada’s Maritime Provinces . McGill-Queen’s University Press. 1998.

- ^ Marquis, In Armageddon’s Shadow

- ^ Beck (2000)

- ^ Kris Inwood, and Phyllis Wagg, "Wealth and Prosperity in Nova Scotia Agriculture, 1851-71." Canadian Historical Review 1994 75(2): 239-264.

- ^ Marilyn Gerriets and Julian Gwyn, "Tariffs, Trade and Reciprocity: Nova Scotia, 1830-1866." Acadiensis 1996 25(2): 62-81. Issn: 0044-5851

- ^ John G. Langley, "Samuel Cunard 1787-1865: 'As Fine a Specimen of a Self-made Man as this Western Continent Can Boast Of.'" Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society 2005 8: 92-115. Issn: 1486-5920

- ^ J.B. Cahill, "STAIRS, JOHN FITZWILLIAM" in Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online (2000) online edition

- ^ James D. Frost, Merchant princes: Halifax's first family of finance, ships, and steel (2003)

- ^ James D. Frost, "Halifax: the Wharf of the Dominion, 1867-1914." Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society 2005 8: 35-48.

- ^ Ian McKay, "'By Wisdom, Wile or War:' The Provincial Workmen's Association and the Struggle for Working-Class Independence in Nova Scotia, 1879-97," Labour/Le Travail, (Fall 1986), 18:13-62 online

- ^ Paul MacEwan, Miners and Steelworkers: Labour in Cape Breton (1976)

- ^ Ian McKay, "History and the Tourist Gaze: The Politics of Commemoration in Nova Scotia, 1935-1964," Acadiensis, Spring 1993, Vol. 22 Issue 2, pp 102-138

- ^ Julian Gwyn and Fazley Siddiq, "Wealth distribution in Nova Scotia during the Confederation era, 1851 and 1871," Canadian Historical Review, Dec 1992, Vol. 73 Issue 4, pp 435-52

- ^ Julian Gwyn, "Golden Age or Bronze Moment? Wealth and Poverty in Nova Scotia: The 1850s and 1860s," Canadian Papers in Rural History, 1992, Vol. 8, pp 195-230

- ^ Rural poverty is the theme of Rusty Bittermann, Robert A. Mackinnon, and Graeme Wynn, "Of inequality and interdependence in the Nova Scotian countryside, 1850-70," Canadian Historical Review, March 1993, Vol. 74 Issue 1, pp 1-43

- ^ The history of the North-west rebellion of 1885: Comprising a full and ... By Charles Pelham Mulvany, Louis Riel, p. 410

- ^ L. D. McCann, "Fragmented Integration: the Nova Scotia Steel and Coal Company and the Anatomy of an Urban-industrial Landscape, c. 1912." Urban History Review 1994 22(2): 139-158.

- ^ John Mellor, The Company Stores: J.B. McLachian and the Cape Breton Coal Miners 1900-1925 (1983)

- ^ Paul Brown, "'Come East, Young Man!' the Politics of Rural Depopulation in Nova Scotia, 1900-1925." Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society1998 1: 47-78.

- ^ Canadian War Museum (2008). "Battle of Paardeberg". Canadian War Museum. Retrieved 2008-05-10. [dead link]

- ^ Canadian War Museum (2008). "Battle of Faber's Put". Canadian War Museum. Retrieved 2008-05-10. [dead link]

- ^ Canadian War Museum (2008). "Battle of Leliefontein". Canadian War Museum. Retrieved 2008-05-10. [dead link]

- ^ http://angloboerwarmuseum.com/Boer70g_hero7_borden1.html

- ^ John Bell. Confederate Seadog: John Taylor Wood in War and Exile. McFarland Publishers. 2002. p. 59

- ^ The Halifax Explosion and the Royal Canadian Navy John Armstrong, University of British Columbia Press, 2002, p.10-11.

- ^ CBC - Halifax Explosion 1917

- ^ Jay White, "Exploding Myths: The Halifax Explosion in Historical Context", Ground Zero: A Reassessment of the 1917 explosion in Halifax Alan Ruffman and Colin D. Howell editors, Nimbus Publishing (1994), p. 266

- ^ T. Stephen Henderson, Angus L. Macdonald: A Provincial Liberal (2007) pp. 3–9.

- ^ E.R. Forbes, Challenging the Regional Stereotype: Essays on the 20th Century Maritimes (1989) p.148.

- ^ Santo Dodaro and Leonard Pluta, The Big Picture: The Antigonish Movement of Eastern Nova Scotia (2012)

- ^ David Frank, J. B. McLachlan: A Biography: The Story of a Legendary Labour Leader and the Cape Breton Coal Miners (1999) p 97

- ^ Penfold Steven, "'Have You No Manhood in You?' Gender and Class in the Cape Breton Coal Towns, 1920-1926." Acadiensis 1994 23(2): 21-44.

- ^ Jennifer Smith, "The Stanfield Government and Social Policy in Nova Scotia: 1956-1967." Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society 2003 6: 1-16.

Bibliography

- Ian McKay and Robin Bates. In the Province of History: The Making of the Public Past in Twentieth-Century Nova Scotia (2010)

- Dr. Ed Whitcomb. A Short History of Nova Scotia. Ottawa. From Sea To Sea Enterprises, 2009. ISBN 978-0-9694667-9-6. 72 pp.

- Duncan Campbell, History of Nova Scotia, for Schools BiblioLife, 2009 ISBN 1-115-65980-4, excerpt

- The quest of the folk : antimodernism and cultural selection in twentieth-century Nova Scotia BY Ian McKay McGill-Queen's University Press, 1994 ISBN 0-7735-1179-2

- Conservative reformer, 1804-1848 - v. 2. The Briton becomes Canadian BY Joseph Howe and J. Murray Beck McGill-Queen's University Press, 1984 ISBN 0-7735-0445-1

- The Supreme Court of Nova Scotia, 1754-2004: from imperial bastion to ...By Philip Girard, Jim Phillips Society for Canadian Legal History, 2004 ISBN 0-8020-8021-9

- Against the Grain: Foresters and Politics in Nova Scotia By Anders Sandberg, Peter Clancy UBC Press, 2000 ISBN 0-7748-0765-2