Nuclear energy policy: Difference between revisions

expand |

|||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

Nuclear power has been relatively unaffected by [[embargo]]es, and uranium is mined in "reliable" countries, including Australia and Canada.<ref name=platts>{{cite news | publisher= Platts |url= http://www.platts.com/Nuclear/Resources/News%20Features/nukeinsight/ | title = Nuclear renaissance faces realities | accessdate=2007-07-13 |id={{Subscription required}}}}</ref><ref name=esat>{{cite paper | publisher= Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Departement of Electrical Engineering of the Faculty of Engineering | author=L. Meeus, K. Purchala, R. Belmans | url= http://www.esat.kuleuven.be/electa/publications/fulltexts/pub_1225.pdf | title = Is it reliable to depend on import? | format=PDF | accessdate=2007-07-13}}</ref> |

Nuclear power has been relatively unaffected by [[embargo]]es, and uranium is mined in "reliable" countries, including Australia and Canada.<ref name=platts>{{cite news | publisher= Platts |url= http://www.platts.com/Nuclear/Resources/News%20Features/nukeinsight/ | title = Nuclear renaissance faces realities | accessdate=2007-07-13 |id={{Subscription required}}}}</ref><ref name=esat>{{cite paper | publisher= Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Departement of Electrical Engineering of the Faculty of Engineering | author=L. Meeus, K. Purchala, R. Belmans | url= http://www.esat.kuleuven.be/electa/publications/fulltexts/pub_1225.pdf | title = Is it reliable to depend on import? | format=PDF | accessdate=2007-07-13}}</ref> |

||

===Nuclear |

===Nuclear history=== |

||

Nuclear proponents and the industry itself have a long history of unfulfilled promises relating to the expected growth and success of nuclear power. For example, there have been many inflated projections of installed nuclear power capacity. In 1973 and 1974, the [[International Atomic Energy Agency]] predicted a worldwide installed nuclear capacity of 3,600 to 5,000 gigawatts by 2000. The IAEAs 1980 projection was for 740 to 1,075 gigawatts of installed capacity by the year 2000. The actual capacity in 2000 was 356 gigawatts.<ref name=mycles/> After the 1986 [[Chernobyl disaster]], the [[Nuclear Energy Agency]] forecasted an installed nuclear capacity of 497 to 646 gigawatts for the year 2000, still 40 to 80 percent above the actual figure. Moreover, unfulfilled promises of on-time construction within budget, and “unlimited cheap, clean, and safe electricity” have been prevalent throughout the history of nuclear power. According to the latest ''[[World Nuclear Industry Status Report]]'', key nuclear indicators including the "number of operating reactors, installed capacity, power generation, and share of total electricity generation all show that the global nuclear industry is in decline".<ref name=mycles>{{cite web |url=http://bos.sagepub.com/content/68/5/8.abstract?etoc |title=2011-2012 world nuclear industry status report |author=[[Mycle Schneider]] and [[Antony Froggatt]] |date=September/October 2012 vol. 68 no. 5 |work=Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists |page=8-22 }}</ref> |

|||

{{Main|Nuclear renaissance}} |

|||

Since about 2001 the term "nuclear renaissance" has been used to refer to a possible [[nuclear power]] industry revival, driven by rising [[Price of petroleum|fossil fuel prices]] and new concerns about meeting [[greenhouse gas]] emission limits.<ref name="intro">[http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/inf104.html The Nuclear Renaissance (by the World Nuclear Association)]</ref> At the same time, various barriers to a nuclear renaissance have been identified. These include: unfavourable economics compared to other sources of energy, slowness in addressing [[climate change]], industrial bottlenecks and personnel shortages in nuclear sector, and the unresolved [[High-level radioactive waste management|nuclear waste]] issue. There are also concerns about more [[nuclear accident]]s, security, and [[nuclear proliferation|nuclear weapons proliferation]].<ref>[[Trevor Findlay]]. [http://www.cigionline.org/library/future-nuclear-energy-2030-and-its-implications-safety-security-and-nonproliferation-overvie The Future of Nuclear Energy to 2030 and its Implications for Safety, Security and Nonproliferation] February 4, 2010.</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://bos.sagepub.com/content/63/3/24.full |title=Obstacles to Nuclear Power |author=Allison Macfarlane |date=May 1, 2007 vol. 63 no. 3 |work=Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists |pages=24–25 }}</ref><ref name=tf2010>Trevor Findlay (2010). [http://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/Nuclear%20Energy%20Futures%20Overview.pdf The Future of Nuclear Energy to 2030 and its Implications for Safety, Security and Nonproliferation: Overview], The Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, pp. 10-11.</ref><ref>M.V. Ramana. Nuclear Power: Economic, Safety, Health, and Environmental Issues of Near-Term Technologies, ''Annual Review of Environment and Resources'', 2009, 34, pp. 144-145.</ref><ref name=iea2009>International Energy Agency, ''World Energy Outlook'', 2009, p. 160.</ref> |

Since about 2001 the term "[[nuclear renaissance]]" has been used to refer to a possible [[nuclear power]] industry revival, driven by rising [[Price of petroleum|fossil fuel prices]] and new concerns about meeting [[greenhouse gas]] emission limits.<ref name="intro">[http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/inf104.html The Nuclear Renaissance (by the World Nuclear Association)]</ref> At the same time, various barriers to a nuclear renaissance have been identified. These include: unfavourable economics compared to other sources of energy, slowness in addressing [[climate change]], industrial bottlenecks and personnel shortages in nuclear sector, and the unresolved [[High-level radioactive waste management|nuclear waste]] issue. There are also concerns about more [[nuclear accident]]s, security, and [[nuclear proliferation|nuclear weapons proliferation]].<ref>[[Trevor Findlay]]. [http://www.cigionline.org/library/future-nuclear-energy-2030-and-its-implications-safety-security-and-nonproliferation-overvie The Future of Nuclear Energy to 2030 and its Implications for Safety, Security and Nonproliferation] February 4, 2010.</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://bos.sagepub.com/content/63/3/24.full |title=Obstacles to Nuclear Power |author=Allison Macfarlane |date=May 1, 2007 vol. 63 no. 3 |work=Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists |pages=24–25 }}</ref><ref name=tf2010>Trevor Findlay (2010). [http://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/Nuclear%20Energy%20Futures%20Overview.pdf The Future of Nuclear Energy to 2030 and its Implications for Safety, Security and Nonproliferation: Overview], The Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, pp. 10-11.</ref><ref>M.V. Ramana. Nuclear Power: Economic, Safety, Health, and Environmental Issues of Near-Term Technologies, ''Annual Review of Environment and Resources'', 2009, 34, pp. 144-145.</ref><ref name=iea2009>International Energy Agency, ''World Energy Outlook'', 2009, p. 160.</ref> |

||

New reactors under construction in Finland and France, which were meant to lead a nuclear renaissance, have been delayed and are running over-budget.<ref name=jk>James Kanter. [http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/29/business/energy-environment/29nuke.html?ref=global-home In Finland, Nuclear Renaissance Runs Into Trouble] ''New York Times'', May 28, 2009.</ref><ref name=greeninc>James Kanter. [http://greeninc.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/05/29/is-the-nuclear-renaissance-fizzling/ Is the Nuclear Renaissance Fizzling?] ''Green'', 29 May 2009.</ref><ref name=rb>Rob Broomby. [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/8138869.stm Nuclear dawn delayed in Finland] ''BBC News'', 8 July 2009.</ref> [[China]] has 27 new reactors under construction,<ref name="Nuclear Power in China">[http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/inf63.html Nuclear Power in China]</ref> and there are also a considerable number of new reactors being built in South Korea, India, and Russia. At least 100 older and smaller reactors will "most probably be closed over the next 10-15 years".<ref name="ditt"/> |

New reactors under construction in Finland and France, which were meant to lead a nuclear renaissance, have been delayed and are running over-budget.<ref name=jk>James Kanter. [http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/29/business/energy-environment/29nuke.html?ref=global-home In Finland, Nuclear Renaissance Runs Into Trouble] ''New York Times'', May 28, 2009.</ref><ref name=greeninc>James Kanter. [http://greeninc.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/05/29/is-the-nuclear-renaissance-fizzling/ Is the Nuclear Renaissance Fizzling?] ''Green'', 29 May 2009.</ref><ref name=rb>Rob Broomby. [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/8138869.stm Nuclear dawn delayed in Finland] ''BBC News'', 8 July 2009.</ref> [[China]] has 27 new reactors under construction,<ref name="Nuclear Power in China">[http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/inf63.html Nuclear Power in China]</ref> and there are also a considerable number of new reactors being built in South Korea, India, and Russia. At least 100 older and smaller reactors will "most probably be closed over the next 10-15 years".<ref name="ditt"/> |

||

| Line 100: | Line 101: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist |

{{Reflist}} |

||

== Further reading == |

== Further reading == |

||

*[[Stephanie Cooke|Cooke, Stephanie]] (2009). ''[[In Mortal Hands: A Cautionary History of the Nuclear Age]]'', Black Inc. |

|||

*[[Mark Diesendorf|Diesendorf, Mark]] (2007). ''[[Greenhouse Solutions with Sustainable Energy]]'', University of New South Wales Press. |

|||

*[[David Elliott (professor)|Elliott, David]] (2007). ''[[Nuclear or Not?|Nuclear or Not? Does Nuclear Power Have a Place in a Sustainable Energy Future?]]'', Palgrave. |

|||

*Falk, Jim (1982). ''Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power'', Oxford University Press. |

|||

* Ferguson, Charles D., [http://books.google.com/books?id=ESVVYtZ98-IC&printsec=frontcover "Nuclear Energy: Balancing Benefits and Risks"], [[Council on Foreign Relations]], 2007 |

* Ferguson, Charles D., [http://books.google.com/books?id=ESVVYtZ98-IC&printsec=frontcover "Nuclear Energy: Balancing Benefits and Risks"], [[Council on Foreign Relations]], 2007 |

||

*[[Amory Lovins|Lovins, Amory B.]] (1977). ''[[Soft energy path|Soft Energy Paths: Towards a Durable Peace]]'', Friends of the Earth International, ISBN 0-06-090653-7 |

|||

*Lovins, Amory B. and John H. Price (1975). ''[[Non-Nuclear Futures: The Case for an Ethical Energy Strategy]]'', Ballinger Publishing Company, 1975, ISBN 0-88410-602-0 |

|||

*[[Ian Lowe|Lowe, Ian]] (2007). ''[[Reaction Time: Climate Change and the Nuclear Option]]'', [[Quarterly Essay]]. |

|||

*[[Ron Pernick|Pernick, Ron]] and [[Clint Wilder]] (2007). ''[[The Clean Tech Revolution|The Clean Tech Revolution: The Next Big Growth and Investment Opportunity]]'', Collins, ISBN 978-0-06-089623-2 |

|||

*[[Mycle Schneider|Schneider, Mycle]], [[Stephen Thomas (professor)|Steve Thomas]], Antony Froggatt, Doug Koplow (August 2009). ''[[The World Nuclear Industry Status Report]]'', [[Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety|German Federal Ministry of Environment, Nature Conservation and Reactor Safety]]. |

|||

*[[Benjamin K. Sovacool|Sovacool, Benjamin K.]] (2011). ''[[Contesting the Future of Nuclear Power]]: A Critical Global Assessment of Atomic Energy'', [[World Scientific]]. |

|||

*Walker, J. Samuel (2004). ''[[Three Mile Island (book)|Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective]]'', University of California Press. |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

Revision as of 07:53, 21 September 2012

Nuclear energy policy is a national and international policy concerning some or all aspects of nuclear energy, such as mining for nuclear fuel, extraction and processing of nuclear fuel from the ore, generating electricity by nuclear power, enriching and storing spent nuclear fuel and nuclear fuel reprocessing.

Nuclear energy policies often include the regulation of energy use and standards relating to the nuclear fuel cycle. Other measures include efficiency standards, safety regulations, emission standards, fiscal policies, and legislation on energy trading, transport of nuclear waste and contaminated materials, and their storage. Governments might subsidize nuclear energy and arrange international treaties and trade agreements about the import and export of nuclear technology, electricity, nuclear waste, and uranium.

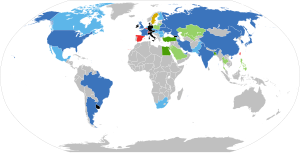

Following the March 2011 Fukushima I nuclear accidents, China, Germany, Switzerland, Israel, Malaysia, Thailand, United Kingdom, and the Philippines are reviewing their nuclear power programs. Indonesia and Vietnam still plan to build nuclear power plants.[1][2][3][4] Thirty-one countries operate nuclear power stations, and there are a considerable number of new reactors being built in China, South Korea, India, and Russia.[5] As of June 2011, countries such as Australia, Austria, Denmark, Greece, Ireland, Latvia, Lichtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, Israel, Malaysia, New Zealand, and Norway remain opposed to nuclear power.[6][7] However, by contrast, most of the prior mentioned countries remain fully in favor, and financially support Nuclear Fusion energy and research, including EU wide funding of the ITER project.[8][9]

Since nuclear energy and nuclear weapons technologies are closely related, military aspirations can act as a factor in energy policy decisions. The fear of nuclear proliferation influences some international nuclear energy policies.

The global picture

After 1986's Chernobyl disaster, public fear of nuclear power led to a virtual halt in reactor construction, and several countries decided to phase out nuclear power altogether.[10] However, increasing energy demand is beginning to require new sources of electric power, and rising fossil fuel prices coupled with new concerns about reducing greenhouse gas emissions (see Climate change mitigation) have sparked heightened interest in nuclear power and predictions of a nuclear renaissance (made possible in part by major improvements in nuclear reactor safety).[11]

As of 2007, 31 countries operated nuclear power plants.[12] Nuclear power tends to be found in nations connected to the largest electrical grids, and so the largest nations (or groups of them) such as China, India, the US, Russia and the European nations all utilize it (see graphic to right).[citation needed] The largest producer of nuclear energy is the United States with 28% of worldwide capacity, followed by France (18%) and Japan (12%).[13] In 2007, there were 439 operating nuclear generating units throughout the world, with a total capacity of about 351 gigawatts.

According to the IAEA, as of September, 2008, nuclear power is projected to remain at a 12.4% to 14.4% share of the world's electricity production through 2030.[14]

Policy issues

Nuclear concerns

Nuclear accidents and radioactive waste disposal are major concerns.[15] Other concerns include nuclear proliferation, the high cost of nuclear power plants, and nuclear terrorism.[15]

Energy security

For some countries, nuclear power affords energy independence. In the words of the French, "We have no coal, we have no oil, we have no gas, we have no choice."[16] Therefore, the discussion of a future for nuclear energy is intertwined with a discussion of energy security and the use of energy mix, including renewable energy development.[citation needed]

Nuclear power has been relatively unaffected by embargoes, and uranium is mined in "reliable" countries, including Australia and Canada.[16][17]

Nuclear history

Nuclear proponents and the industry itself have a long history of unfulfilled promises relating to the expected growth and success of nuclear power. For example, there have been many inflated projections of installed nuclear power capacity. In 1973 and 1974, the International Atomic Energy Agency predicted a worldwide installed nuclear capacity of 3,600 to 5,000 gigawatts by 2000. The IAEAs 1980 projection was for 740 to 1,075 gigawatts of installed capacity by the year 2000. The actual capacity in 2000 was 356 gigawatts.[18] After the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, the Nuclear Energy Agency forecasted an installed nuclear capacity of 497 to 646 gigawatts for the year 2000, still 40 to 80 percent above the actual figure. Moreover, unfulfilled promises of on-time construction within budget, and “unlimited cheap, clean, and safe electricity” have been prevalent throughout the history of nuclear power. According to the latest World Nuclear Industry Status Report, key nuclear indicators including the "number of operating reactors, installed capacity, power generation, and share of total electricity generation all show that the global nuclear industry is in decline".[18]

Since about 2001 the term "nuclear renaissance" has been used to refer to a possible nuclear power industry revival, driven by rising fossil fuel prices and new concerns about meeting greenhouse gas emission limits.[19] At the same time, various barriers to a nuclear renaissance have been identified. These include: unfavourable economics compared to other sources of energy, slowness in addressing climate change, industrial bottlenecks and personnel shortages in nuclear sector, and the unresolved nuclear waste issue. There are also concerns about more nuclear accidents, security, and nuclear weapons proliferation.[20][21][22][23][24]

New reactors under construction in Finland and France, which were meant to lead a nuclear renaissance, have been delayed and are running over-budget.[25][26][27] China has 27 new reactors under construction,[28] and there are also a considerable number of new reactors being built in South Korea, India, and Russia. At least 100 older and smaller reactors will "most probably be closed over the next 10-15 years".[5]

In March 2011 the nuclear emergencies at Japan's Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant and other nuclear facilities raised questions among some commentators over the future of the renaissance.[29][30][31][32][33] Following the Fukushima I accidents, the International Energy Agency halved its estimate of additional nuclear generating capacity to be built by 2035.[34] Platts has reported that "the crisis at Japan's Fukushima nuclear plants has prompted leading energy-consuming countries to review the safety of their existing reactors and cast doubt on the speed and scale of planned expansions around the world".[35]

A study by UBS, reported on April 12, predicts that around 30 nuclear plants may be closed world-wide, with those located in seismic zones or close to national boundaries being the most likely to shut. The analysts believe that 'even pro-nuclear counties such as France will be forced to close at least two reactors to demonstrate political action and restore the public acceptability of nuclear power', noting that the events at Fukushima 'cast doubt on the idea that even an advanced economy can master nuclear safety'.[36]

Reactions to Fukushima

Following the Fukushima nuclear disaster, Germany has permanently shut down eight of its reactors and pledged to close the rest by 2022.[37] The Italians have voted overwhelmingly to keep their country non-nuclear.[38] Switzerland and Spain have banned the construction of new reactors.[39] Japan’s prime minister has called for a dramatic reduction in Japan’s reliance on nuclear power.[40] Taiwan’s president did the same. Mexico has sidelined construction of 10 reactors in favor of developing natural-gas-fired plants.[41] Belgium is considering phasing out its nuclear plants, perhaps as early as 2015.[39]

China—nuclear power’s largest prospective market—suspended approvals of new reactor construction while conducting a lengthy nuclear-safety review.[33][42] Neighboring India, another potential nuclear boom market, has encountered effective local opposition, growing national wariness about foreign nuclear reactors, and a nuclear liability controversy that threatens to prevent new reactor imports. There have been mass protests against the French-backed 9900 MW Jaitapur Nuclear Power Project in Maharashtra and the 2000 MW Koodankulam Nuclear Power Plant in Tamil Nadu. The state government of West Bengal state has also refused permission to a proposed 6000 MW facility near the town of Haripur that intended to host six Russian reactors.[43]

There is little support across the world for building new nuclear reactors, a 2011 poll for the BBC indicates. The global research agency GlobeScan, commissioned by BBC News, polled 23,231 people in 23 countries from July to September 2011, several months after the Fukushima nuclear disaster. In countries with existing nuclear programmes, people are significantly more opposed than they were in 2005, with only the UK and US bucking the trend. Most believe that boosting energy efficiency and renewable energy can meet their needs.[44]

Just 22% agreed that "nuclear power is relatively safe and an important source of electricity, and we should build more nuclear power plants". In contrast, 71% thought their country "could almost entirely replace coal and nuclear energy within 20 years by becoming highly energy-efficient and focusing on generating energy from the Sun and wind". Globally, 39% want to continue using existing reactors without building new ones, while 30% would like to shut everything down now.[44]

Policies by territory

Following the March 2011 Fukushima I nuclear accidents, China, Germany, Switzerland, Israel, Malaysia, Thailand, United Kingdom, and the Philippines are reviewing their nuclear power programs. Indonesia and Vietnam still plan to build nuclear power plants.[1][2][3][4] Countries such as Australia, Austria, Denmark, Greece, Ireland, Luxembourg, Portugal, New Zealand, and Norway remain opposed to nuclear power.[45]

See also

References

- ^ a b Jo Chandler (March 19, 2011). "Is this the end of the nuclear revival?". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ a b Aubrey Belford (March 17, 2011). "Indonesia to Continue Plans for Nuclear Power". New York Times.

- ^ a b Israel Prime Minister Netanyahu: Japan situation has "caused me to reconsider" nuclear power Piers Morgan on CNN, published 2011-03-17, accessed 2011-03-17

- ^ a b Israeli PM cancels plan to build nuclear plant xinhuanet.com, published 2011-03-18, accessed 2011-03-17

- ^ a b Michael Dittmar. Taking stock of nuclear renaissance that never was Sydney Morning Herald, August 18, 2010.

- ^ "Nuclear power: When the steam clears". The Economist. March 24, 2011.

- ^ Duroyan Fertl (June 5, 2011). "Germany: Nuclear power to be phased out by 2022". Green Left.

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/4629239.stm

- ^ http://www.ncpst.ie/news-and-events/association_euratom_dcu.html

- ^ Research and Markets: International Perspectives on Energy Policy and the Role of Nuclear Power Reuters, May 6, 2009.

- ^

"The Nuclear Renaissance". World Nuclear Association. 2009. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mycle Schneider, Steve Thomas, Antony Froggatt, Doug Koplow (August 2009). The World Nuclear Industry Status Report, German Federal Ministry of Environment, Nature Conservation and Reactor Safety, p. 6.

- ^ "Survey of energy resources" (PDF). World Energy Council. 2004. Retrieved 2007-07-13.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Energy, Electricity and Nuclear Power Estimates for the Period up to 2030" (PDF). International Atomic Energy Agency. September2008. Retrieved 2008-09-08.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Brian Martin. Opposing nuclear power: past and present, Social Alternatives, Vol. 26, No. 2, Second Quarter 2007, pp. 43-47.

- ^ a b "Nuclear renaissance faces realities". Platts. (subscription required). Retrieved 2007-07-13.

- ^ L. Meeus, K. Purchala, R. Belmans. "Is it reliable to depend on import?" (PDF). Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Departement of Electrical Engineering of the Faculty of Engineering. Retrieved 2007-07-13.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Mycle Schneider and Antony Froggatt (September/October 2012 vol. 68 no. 5). "2011-2012 world nuclear industry status report". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. p. 8-22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ The Nuclear Renaissance (by the World Nuclear Association)

- ^ Trevor Findlay. The Future of Nuclear Energy to 2030 and its Implications for Safety, Security and Nonproliferation February 4, 2010.

- ^ Allison Macfarlane (May 1, 2007 vol. 63 no. 3). "Obstacles to Nuclear Power". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. pp. 24–25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Trevor Findlay (2010). The Future of Nuclear Energy to 2030 and its Implications for Safety, Security and Nonproliferation: Overview, The Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, pp. 10-11.

- ^ M.V. Ramana. Nuclear Power: Economic, Safety, Health, and Environmental Issues of Near-Term Technologies, Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 2009, 34, pp. 144-145.

- ^ International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook, 2009, p. 160.

- ^ James Kanter. In Finland, Nuclear Renaissance Runs Into Trouble New York Times, May 28, 2009.

- ^ James Kanter. Is the Nuclear Renaissance Fizzling? Green, 29 May 2009.

- ^ Rob Broomby. Nuclear dawn delayed in Finland BBC News, 8 July 2009.

- ^ Nuclear Power in China

- ^ Nuclear Renaissance Threatened as Japan’s Reactor Struggles Bloomberg, published March 2011, accessed 2011-03-14

- ^ Analysis: Nuclear renaissance could fizzle after Japan quake Reuters, published 2011-03-14, accessed 2011-03-14

- ^ Japan nuclear woes cast shadow over U.S. energy policy Reuters, published 2011-03-13, accessed 2011-03-14

- ^ Nuclear winter? Quake casts new shadow on reactors MarketWatch, published 2011-03-14, accessed 2011-03-14

- ^ a b Will China's nuclear nerves fuel a boom in green energy? Channel 4, published 2011-03-17, accessed 2011-03-17

- ^ "Gauging the pressure". The Economist. 28 April 2011.

- ^ "NEWS ANALYSIS: Japan crisis puts global nuclear expansion in doubt". Platts. 21 March 2011.

- ^ Nucléaire : une trentaine de réacteurs dans le monde risquent d'être fermés Les Échos, published 2011-04-12, accessed 2011-04-15

- ^ Annika Breidthardt (May 30, 2011). "German government wants nuclear exit by 2022 at latest". Reuters.

- ^ "Italy Nuclear Referendum Results". June 13, 2011.

- ^ a b Henry Sokolski (Nov 28, 2011). "Nuclear Power Goes Rogue". Newsweek.

- ^ Tsuyoshi Inajima and Yuji Okada (Oct 28, 2011). "Nuclear Promotion Dropped in Japan Energy Policy After Fukushima". Bloomberg.

- ^ Carlos Manuel Rodriguez (Nov 4, 2011). "Mexico Scraps Plans to Build 10 Nuclear Power Plants in Favor of Using Gas". Bloomberg Businessweek.

- ^ By the CNN Wire Staff. "China freezes nuclear plant approvals - CNN.com". Edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Siddharth Srivastava (27 October 2011). "India's Rising Nuclear Safety Concerns". Asia Sentinel.

- ^ a b Richard Black (25 November 2011). "Nuclear power 'gets little public support worldwide'". BBC News.

- ^ "Nuclear power: When the steam clears". The Economist. March 24, 2011.

Further reading

- Cooke, Stephanie (2009). In Mortal Hands: A Cautionary History of the Nuclear Age, Black Inc.

- Diesendorf, Mark (2007). Greenhouse Solutions with Sustainable Energy, University of New South Wales Press.

- Elliott, David (2007). Nuclear or Not? Does Nuclear Power Have a Place in a Sustainable Energy Future?, Palgrave.

- Falk, Jim (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press.

- Ferguson, Charles D., "Nuclear Energy: Balancing Benefits and Risks", Council on Foreign Relations, 2007

- Lovins, Amory B. (1977). Soft Energy Paths: Towards a Durable Peace, Friends of the Earth International, ISBN 0-06-090653-7

- Lovins, Amory B. and John H. Price (1975). Non-Nuclear Futures: The Case for an Ethical Energy Strategy, Ballinger Publishing Company, 1975, ISBN 0-88410-602-0

- Lowe, Ian (2007). Reaction Time: Climate Change and the Nuclear Option, Quarterly Essay.

- Pernick, Ron and Clint Wilder (2007). The Clean Tech Revolution: The Next Big Growth and Investment Opportunity, Collins, ISBN 978-0-06-089623-2

- Schneider, Mycle, Steve Thomas, Antony Froggatt, Doug Koplow (August 2009). The World Nuclear Industry Status Report, German Federal Ministry of Environment, Nature Conservation and Reactor Safety.

- Sovacool, Benjamin K. (2011). Contesting the Future of Nuclear Power: A Critical Global Assessment of Atomic Energy, World Scientific.

- Walker, J. Samuel (2004). Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective, University of California Press.

External links

- NEI Public Policy Information

- Robert J. Duffy. Nuclear Politics in America: A History and Theory of Government Regulation (Studies in Government and Public Policy). Paperback. 1997. ISBN 0-7006-0853-2.

- Carlton Stoiber, Alec Baer, Norbert Pelzer, Wolfram Tonhauser, Handbook on Nuclear Law, IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency), 2003.

- Annotated bibliography for nuclear power from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues