Brian Moore (novelist): Difference between revisions

Headhitter (talk | contribs) m Added wikilink: Robert Fulford |

Headhitter (talk | contribs) →Bibliography: Added new section: Books about Brian Moore |

||

| Line 123: | Line 123: | ||

===Interviews === |

===Interviews === |

||

*[[Robert Fulford (journalist)|Fulford, Robert]]. "Robert Fulford Interviews Brian Moore". ''[[Tamarack Review]]'' 23 (1962), pp.5-18 |

*[[Robert Fulford (journalist)|Fulford, Robert]]. "Robert Fulford Interviews Brian Moore". ''[[Tamarack Review]]'' 23 (1962), pp.5-18 |

||

*Dahlie, Hallvard. "Brian Moore: An Interview". ''Tamarack Review 46'' (1968), pp.7-29 |

*Dahlie, Hallvard. "Brian Moore: An Interview". ''Tamarack Review 46'' (1968), pp.7-29 |

||

*Sale, Richard. "An Interview in London with Brian Moore". ''Studies in the Novel 1'' (Spring 1969), pp.67-80 |

*Sale, Richard. "An Interview in London with Brian Moore". ''Studies in the Novel 1'' (Spring 1969), pp.67-80 |

||

*Cameron, Donald. "Brian Moore". ''Conversations with Canadian Novelists, 2''. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada (1973), pp.64-85 |

*Cameron, Donald. "Brian Moore". ''Conversations with Canadian Novelists, 2''. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada (1973), pp.64-85 |

||

*Graham, John. "Brian Moore". ''The Writer's Voice'', ed. George Garrett. New York: Morrow (1973), pp.51-74 |

*Graham, John. "Brian Moore". ''The Writer's Voice'', ed. George Garrett. New York: Morrow (1973), pp.51-74 |

||

* Bray, Richard T., ed. "A Conversation with Brian Moore". ''Critic: A Catholic Review of Books and the Arts'' 35 (Fall 1976), pp.42-48 |

* Bray, Richard T., ed. "A Conversation with Brian Moore". ''Critic: A Catholic Review of Books and the Arts'' 35 (Fall 1976), pp.42-48 |

||

*De Santana, Hubert. "Interview with Brian Moore". ''[[Maclean's]]'' (11 July 1977), pp.4-7 |

*De Santana, Hubert. "Interview with Brian Moore". ''[[Maclean's]]'' (11 July 1977), pp.4-7 |

||

===Books about Brian Moore=== |

|||

*[[Diana Athill|Athill, Diana]]. ''Stet: a memoir'', London: [[Granta]] ISBN 1-86207-388-0, 2000 |

|||

*Craig, Patricia. ''Brian Moore: A Biography'', 2002 |

|||

*Dahlie, Hallvard. ''Brian Moore''. Toronto: The Copp Clark Publishing Co., 1969. |

|||

*Flood, Jeanne. ''Brian Moore''. Lewisburg, Penn.: Bucknell University Press; London: Associated University Presses, 1974 |

|||

*Foster, John Wilson. ''Forces and Themes in Ulster Fiction''. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1974, pp. 122-130; 151-185 |

|||

*Dahlie, Hallvard. ''Brian Moore''. Boston: G.K. Hall and Company, 1981 |

|||

*McSweeney, Kerry. ''Four Contemporary Novelists''. Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press; London: Scolar Press, 1983, pp. 55-99 |

|||

*O'Donoghue, Jo. ''Brian Moore: A Critical Study''. Montreal and Kingston: McGill University Press, 1991 |

|||

*Sampson, Denis. ''Brian Moore: The Chameleon Novelist'', 1998 |

|||

*Hicks, Patrick. ''Brian Moore and the Meaning of the Past'' (2007) |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 07:59, 29 August 2012

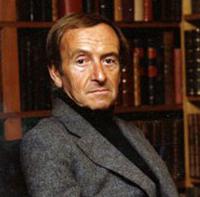

Brian Moore | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 25 August 1921 Belfast, Northern Ireland, UK |

| Died | 11 January 1999 (aged 77) Malibu, California, US |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Notable awards | James Tait Black Memorial Prize (1975) Governor General's Award for English language fiction (1960 and 1975) |

Brian Moore (first name /briːˈæn/ bree-an; 25 August 1921 – 11 January 1999) was a novelist and screenwriter from Northern Ireland[1][2] who emigrated to Canada and later lived in the United States. He was acclaimed for the descriptions in his novels of life in Northern Ireland after the Second World War, in particular his explorations of the inter-communal divisions of The Troubles. He was awarded the James Tait Black Memorial Prize in 1975 and the inaugural Sunday Express Book of the Year award in 1987, and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize three times.[3] Moore also wrote screenplays and several of his books were made into films.

Biography

Moore was born and grew up in Belfast and was educated at St Malachy's College.[4]His father, James Bernard Moore, was a prominent surgeon and the first Catholic to sit on the senate of Queen’s University[5] and his mother, Eileen McFadden Moore, was a nurse.[6][7] He grew up with eight siblings in a large Roman Catholic family, but reportedly rejected that faith early in life. [citation needed] Some of his novels feature staunchly anti-doctrinaire and anti-clerical themes, and he in particular spoke strongly about the effect of the Church on life in Ireland. A recurring theme in his novels is the concept of the Catholic priesthood. On several occasions he explores the idea of a priest losing his faith. These works were criticized by his sister, a Roman Catholic nun. [citation needed] At the same time, several of his novels are deeply sympathetic and affirming portrayals of the struggles of faith and religious commitment, Black Robe most prominently.

He was a volunteer air raid warden during the bombing of Belfast by the Luftwaffe. He also served as a civilian with the British Army in North Africa, Italy and France. After the war ended he worked in Eastern Europe for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. He emigrated to Canada in 1948, worked as a reporter for the Montreal Gazette, and became a Canadian citizen. While eventually making his primary residence in California, Moore continued to live part of each year in Canada up to his death.[7] He taught creative writing at UCLA.[8]

Moore lived in Canada from 1948 to 1958, and wrote his first novels there.[9] His earliest novels were thrillers, published under his own name or using the pseudonyms Bernard Mara or Michael Bryan.[10] Moore's first novel outside the genre, Judith Hearne, remains among his most highly regarded. The book was rejected by ten American publishers before being accepted by a British publisher.[7] It was made into a film, with British actress Maggie Smith playing the lonely spinster who is the book/film's title character.[7]

Other novels by Moore were adapted for the screen, including Intent to Kill, The Luck of Ginger Coffey, Catholics, Black Robe, Cold Heaven, and The Statement. He co-wrote the screenplay for Alfred Hitchcock's Torn Curtain, and wrote The Blood of Others, based on the novel Le Sang des autres by Simone de Beauvoir.

Death

Brian Moore died in 1999 at his home in Malibu, California, aged 77, from pulmonary fibrosis. He had been working on a novel about the 19th-century French symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud.[11]

Personal life

Moore was married twice — in 1951 to Jacqueline Sirois and in 1966 to Jean Denny.[6][12]

Legacy

The Creative Writers Network in Northern Ireland launched in 1996 the Brian Moore Short Story Awards, which are now open to all authors of Irish descent. Previous judges have included Glenn Patterson, Lionel Shriver, Carlo Gebler and Maeve Binchy.[13]

Moore has been the subject of two biographies, Brian Moore: The Chameleon Novelist (1998) by Denis Sampson and Brian Moore: A Biography (2002) by Patricia Craig.[14] Brian Moore and the Meaning of the Past (2007) by Patrick Hicks provides a critical retrospective of Moore's works.

Information about the publishing of Moore's novel, Judith Hearne, and the break-up of his marriage can be found in Diana Athill's memoir, Stet (2000).[15] Moore's archives, which include unfilmed screenplays, drafts of various novels, working notes, a 42-volume journal (1957–1998), and his correspondence[1]], are now at The Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, at the University of Texas at Austin.[16]

Prizes and honours

- 1960 Governor General's Award for Fiction (for The Luck of Ginger Coffey)

- 1975 James Tait Black Memorial Prize For Fiction (for The Great Victorian Collection)

- 1975 Governor General's Award for Fiction (for The Great Victorian Collection)

- 1976 Nominee, Booker Prize (for The Doctor's Wife)

- 1987 Nominee, Booker Prize (for The Colour of Blood)

- 1987 Sunday Express Book of the Year (for The Colour of Blood)

- 1990 Nominee, Booker Prize (for Lies of Silence)

Bibliography

Non-fiction

- Canada (1963)

Novels

- Wreath for a Redhead (1951) (U.S. title: Sailor's Leave)

- The Executioners (1951)

- French for Murder (1954) (as Bernard Mara)

- A Bullet for My Lady (1955) (as Bernard Mara) [2]

- Judith Hearne (1955) (reprinted as The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne)

- This Gun for Gloria (1957) (as Bernard Mara)

- Intent to Kill (1957) (as Michael Bryan)

- The Feast of Lupercal (1957) (reprinted as A Moment of Love, Ger 1964: Saturnischer Tanz)

- Murder in Majorca (1957) (as Michael Bryan)

- The Luck of Ginger Coffey (1960)

- An Answer from Limbo (1962)

- The Emperor of Ice-Cream (1965)

- I Am Mary Dunne (1968)

- Fergus (1970)

- The Revolution Script (1971)

- Catholics (1972, Ger 1975: Katholiken)

- The Great Victorian Collection (1975) Ger 1978: Die Große Viktorianische Sammlung)

- The Doctor's Wife (1976)

- The Mangan Inheritance (1979, Ger 1999: Mangans Vermächtnis)

- The Temptation of Eileen Hughes (1981)

- Cold Heaven (1983)

- Black Robe (1985, Ger 1987: Schwarzrock)

- The Colour of Blood (1987, Ger 1989: Die Farbe des Blutes)

- Lies of Silence (1990)

- No Other Life (1993)

- The Statement (1995, Ger 1997: Hetzjagd)

- The Magician's Wife (1997)

Short story collection

- Two Stories (1978) Northridge, California: Santa Susana Press. Contains "Uncle T" and "Preliminary Pages for a Work of Revenge"

Short stories

- "Sassenach", Northern Review 5 (October-November 1951)

- "Fly Away Finger, Fly Away Thumb", London Mystery Magazine, 17, September 1953 [3]; reprinted in Great Irish Tales of Horror, ed. Peter Haining, Souvenir Press 1995

- "Lion of the Afternoon", The Atlantic, November 1957

- "Next Thing was Kansas City", The Atlantic, February 1959

- "Grieve for the Dear Departed", The Atlantic, August 1959

- "Uncle T", Gentleman's Quarterly, November 1960

- "Preliminary Pages for a Work of Revenge", Midstream 7 (Winter 1961)

- "Hearts and Flowers", The Spectator, November 24, 1961

- "Off the Track", Ten for Wednesday Night, ed. Robert Weaver. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Ltd, 1961, pp. 159-167

- "The Sight", Irish Ghost Stories, ed. Joseph Hone. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1977, pp. 100-119; reprinted in Black Water, ed. Alberto Manguel, Picador 1983; reprinted in The Oxford Book of Canadian Ghost Stories, ed. Alberto Manguel, Toronto: Oxford University Press 1990

- "A Vocation", short story contribution for the Verbal Arts Centre project, 1998

- "A Bed in America" (unpublished; later used in Hitchcock film Torn Curtain)

- "A Matter of Faith" (unpublished)

Playscripts

Screenplays

- The Luck of Ginger Coffey (1964)

- Torn Curtain (1966)

- Catholics (1973)

- The Blood of Others (1984)

- The Sight (1985),[17] a half-hour drama based on a short story by Moore

- Il Giorno prima (Control) (1987)

- Black Robe (1991)

Other films on Moore or based on his work

- Intent to Kill (1958), a film with a screenplay by Jimmy Sangster, based on the novel written by Moore as Michael Bryan

- Uncle T (1985),[18] a half-hour drama, with a script by Gerald Wexler, based on a short story by Moore

- The Lonely Passion of Brian Moore (1986)[4][19] a documentary featuring Moore and looking at what inspired his work

- The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne (1987), a film with a screenplay by Peter Nelson based on Moore's novel

- Cold Heaven (film) (1991), a film with a screenplay by Allan Scott based on Moore's novel

- The Statement (2003) a film with a screenplay by Ronald Harwood based on Moore's novel

Interviews

- Fulford, Robert. "Robert Fulford Interviews Brian Moore". Tamarack Review 23 (1962), pp.5-18

- Dahlie, Hallvard. "Brian Moore: An Interview". Tamarack Review 46 (1968), pp.7-29

- Sale, Richard. "An Interview in London with Brian Moore". Studies in the Novel 1 (Spring 1969), pp.67-80

- Cameron, Donald. "Brian Moore". Conversations with Canadian Novelists, 2. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada (1973), pp.64-85

- Graham, John. "Brian Moore". The Writer's Voice, ed. George Garrett. New York: Morrow (1973), pp.51-74

- Bray, Richard T., ed. "A Conversation with Brian Moore". Critic: A Catholic Review of Books and the Arts 35 (Fall 1976), pp.42-48

- De Santana, Hubert. "Interview with Brian Moore". Maclean's (11 July 1977), pp.4-7

Books about Brian Moore

- Athill, Diana. Stet: a memoir, London: Granta ISBN 1-86207-388-0, 2000

- Craig, Patricia. Brian Moore: A Biography, 2002

- Dahlie, Hallvard. Brian Moore. Toronto: The Copp Clark Publishing Co., 1969.

- Flood, Jeanne. Brian Moore. Lewisburg, Penn.: Bucknell University Press; London: Associated University Presses, 1974

- Foster, John Wilson. Forces and Themes in Ulster Fiction. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1974, pp. 122-130; 151-185

- Dahlie, Hallvard. Brian Moore. Boston: G.K. Hall and Company, 1981

- McSweeney, Kerry. Four Contemporary Novelists. Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press; London: Scolar Press, 1983, pp. 55-99

- O'Donoghue, Jo. Brian Moore: A Critical Study. Montreal and Kingston: McGill University Press, 1991

- Sampson, Denis. Brian Moore: The Chameleon Novelist, 1998

- Hicks, Patrick. Brian Moore and the Meaning of the Past (2007)

References

- ^ "Brian Moore: Forever influenced by loss of faith". BBC Online. 12 January 1999. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Cronin, John (13 January 1999). "Obituary: Shores of Exile". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ "Brian Moore". The Man Booker Prizes. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ Spencer, Clare (6 May 2011). "Why do some schools produce clusters of celebrities?". BBC News. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "Brian Moore". CultureNorthernIreland. 25 November 2008. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ a b Flood, Jeanne (1974). "Brian Moore". Bucknell University Press. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d Smith, Denitia (12 January 1999). "Brian Moore, Prolific Novelist on Diverse Themes, Dies at 77". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ^ "Brian Moore". New York Review Books. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ Lynch, Gerald. "Brian Moore". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ^ a b Sampson, Denis. Brian Moore: The Chameleon Novelist. Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 1998

- ^ Fulford, Robert (12 January 1999). "A writer who never failed to surprise his readers". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ^ Craig, Patricia (2002). "Brian Moore: A Biography". Bloomsbury Publishing. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ "Brian Moore Short Story Awards". CultureNorthernIreland. 9 January 2009. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "Patricia Craig: Editor, anthologist and biographer of Brian Moore". CultureNorthernIreland. 21 January 2009. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ Athill, Diana (2000) Stet: a memoir, London: Granta ISBN 1-86207-388-0

- ^ a b "Brian Moore: A Preliminary Inventory of His Papers". Harry Ransom Center. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ^ "Our Collection: The Sight". National Film Board of Canada. 2 May 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "Uncle T". National Film Board of Canada. 2 May 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "The Lonely Passion of Brian Moore". National Film Board of Canada. 2 May 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

Further reading

- Schumacher, Antje, Brian Moore's Black Robe: Novel, Screenplay(s) and Film (European University Studies. Series 14: Anglo-Saxon Language and Literature. Vol. 494), Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang (2010) Language: English ISBN-10: 3631603215 ISBN-13: 978-363160321

External links

- Brian Moore at IMDb

- Obituary from the BBC

- L.A. Weekly obituary

- Doubt in the Novel - Brian Moore's Cold Heaven

See also

- 1921 births

- 1999 deaths

- Novelists from Northern Ireland

- Short story writers from Northern Ireland

- Screenwriters from Northern Ireland

- Immigrants to Canada from Northern Ireland

- Naturalized citizens of Canada

- Expatriates from Northern Ireland in the United States

- Governor General's Award winning fiction writers

- Genie Award winners for Best Screenplay

- People educated at St Malachy's College

- People from Belfast

- Deaths from pulmonary fibrosis

- Disease-related deaths in California