Paroxetine: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 504116226 by 80.201.109.190 (talk) |

→Controversy: expand |

||

| Line 169: | Line 169: | ||

The court documents released as a result of one of the lawsuits in October 2008 indicated that GSK "and/or researchers may have suppressed or obscured suicide risk data during clinical trials" of paroxetine. One of the investigators, "[[Charles Nemeroff]], former chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at [[Emory University]], was the first big name 'outed' ...In early October 2008, Nemeroff stepped down as department chair amid revelations that he had received over $960,000 from GSK in 2006, yet reported less than $35,000 to the school. Subsequent investigations revealed payments totaling more than $2.5 million from drug companies between 2000 and 2006, yet only a fraction was disclosed."<ref>{{cite journal |author=Samson K |title=Senate probe seeks industry payment data on individual academic researchers |journal=Ann. Neurol. |volume=64 |issue=6 |pages=A7–9 |year=2008 |month=December |pmid=19107985 |doi=10.1002/ana.21271 }}</ref> |

The court documents released as a result of one of the lawsuits in October 2008 indicated that GSK "and/or researchers may have suppressed or obscured suicide risk data during clinical trials" of paroxetine. One of the investigators, "[[Charles Nemeroff]], former chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at [[Emory University]], was the first big name 'outed' ...In early October 2008, Nemeroff stepped down as department chair amid revelations that he had received over $960,000 from GSK in 2006, yet reported less than $35,000 to the school. Subsequent investigations revealed payments totaling more than $2.5 million from drug companies between 2000 and 2006, yet only a fraction was disclosed."<ref>{{cite journal |author=Samson K |title=Senate probe seeks industry payment data on individual academic researchers |journal=Ann. Neurol. |volume=64 |issue=6 |pages=A7–9 |year=2008 |month=December |pmid=19107985 |doi=10.1002/ana.21271 }}</ref> |

||

The suppression of unfavorable research findings on Paxil by GSK — and the legal discovery process that uncovered it — is the subject of [[Alison Bass]]'s 2008 book ''Side Effects: A Prosecutor, a Whistleblower, and a Bestselling Antidepressant on Trial''.<ref>Bass, Alison (2008), ''Side Effects: A Prosecutor, a Whistleblower, and a Bestselling Antidepressant on Trial'', [[Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill]].</ref> |

The suppression of unfavorable research findings on Paxil by GSK — and the legal discovery process that uncovered it — is the subject of [[Alison Bass]]'s 2008 book ''[[Side Effects (book)|Side Effects: A Prosecutor, a Whistleblower, and a Bestselling Antidepressant on Trial]]''. The book chronicles the lives of two women - a prosecutor and a [[whistleblower]] - who exposed deception in the research and marketing of Paxil. The book shows the connections between pharmaceutical giant [[GlaxoSmithKline]], a top Ivy League research institution, and the government agency designed to protect the public - conflicted relationships that arguably compromised the health and safety of vulnerable children. ''Side Effects'' received the NASW [[Science in Society Journalism Awards|Science in Society Award]] for 2009.<ref>http://www.nasw.org/mt-archives/2009/09/scienceinsociety-journalism-aw-1.htm</ref><ref>Bass, Alison (2008), ''[[Side Effects (book)|Side Effects: A Prosecutor, a Whistleblower, and a Bestselling Antidepressant on Trial]]'', [[Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill]].</ref> |

||

In 2012 the U.S. Justice Department announced that GSK had agreed to plead guilty and pay a $3 billion fine, in part for promoting the use of Paxil for children.<ref>{{cite news|title=Glaxo Agrees to Pay $3 Billion in Fraud Settlement|newspaper=The New York Times|date=July 2, 2012|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/03/business/glaxosmithkline-agrees-to-pay-3-billion-in-fraud-settlement.html}}</ref> |

In 2012 the U.S. Justice Department announced that GSK had agreed to plead guilty and pay a $3 billion fine, in part for promoting the use of Paxil for children.<ref>{{cite news|title=Glaxo Agrees to Pay $3 Billion in Fraud Settlement|newspaper=The New York Times|date=July 2, 2012|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/03/business/glaxosmithkline-agrees-to-pay-3-billion-in-fraud-settlement.html}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 02:01, 15 August 2012

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Paxil |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a698032 |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Completely absorbed from GI, but extensive first-pass metabolism in the liver; Tmax 4.9 (with meals) to 6.4 hours (fasting) |

| Protein binding | 93–95% |

| Metabolism | Extensive, hepatic (mostly CYP2D6-mediated) |

| Elimination half-life | 24 hours (range 3–65 hours) |

| Excretion | 64% in urine, 36% in bile |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.112.096 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

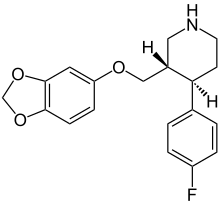

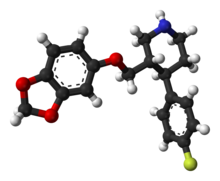

| Formula | C19H20FNO3 |

| Molar mass | 329.3 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Paroxetine (also known by the trade names Aropax, Paxil, Seroxat, Sereupin) is an antidepressant drug of the SSRI type. Paroxetine is used to treat major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder and generalized anxiety disorder[2] in adult outpatients.

Marketing of the drug began in 1992 by the pharmaceutical company SmithKline Beecham, now GlaxoSmithKline. Generic formulations have been available since 2003 when the patent expired.[3] On July 2, 2012, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) was to pay $3bn (£1.9bn) in the largest healthcare fraud settlement in US history. The case concerns the drugs Paxil, Wellbutrin and Avandia.[4]

In adults, the efficacy of paroxetine for depression is comparable to that of older tricyclic antidepressants, with fewer side effects and lower toxicity.[5][6] Differences with newer antidepressants are subtler and mostly confined to side effects. It shares the common side effects and contraindications of other SSRIs, with high rates of nausea, somnolence, and sexual side effects. Unlike two other popular SSRI antidepressants, fluoxetine and sertraline, paroxetine is associated with clinically significant weight gain.[7] Pediatric trials of paroxetine for depression did not demonstrate statistical efficacy better than placebo.[8][9][10]

Discontinuing paroxetine is associated with a high risk of withdrawal syndrome.[11][12] Due to the increased risk of birth defects, pregnant women or women planning to become pregnant are recommended to consult with their physician.[13][14][15][16][17]

Medical uses

Paroxetine is primarily used to treat the symptoms of major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD),[18] social phobia/social anxiety disorder,[19] and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).[20]

Paroxetine was the first antidepressant formally approved in the United States for the treatment of panic attacks.[21]

Investigational

Several studies have suggested that paroxetine can be used in the treatment of premature ejaculation. In particular, intravaginal ejaculation latency time (IELT) was found to increase with 6-13-fold, which was somewhat longer than the delay achieved by the treatment with other SSRIs (fluvoxamine, fluoxetine, sertraline, and citalopram).[22][23][24] However, paroxetine taken acutely ("on demand") 3–10 hours before coitus resulted only in a "clinically irrelevant and sexually unsatisfactory" 1.5-fold delay of ejaculation and was inferior to clomipramine, which induced a fourfold delay.[24] The reason it causes a delay in ejaculation is because it greatly reduces sex drive. In some cases, causing an inability to gain an erection or ejaculate. SSRIs are also effective in the treatment of severe premenstrual syndrome;[25] however, paroxetine is contraindicated in women who may become pregnant due to its teratogenicity and its high risk of withdrawal syndrome in both adults and neonates. See Paroxetine and pregnancy.

There is also evidence that paroxetine may be effective in the treatment of compulsive gambling[26] and hot flashes.[27]

Benefits of paroxetine prescription for diabetic neuropathy[28] or chronic tension headache.[29] are uncertain.

Emerging evidence shows that antipsychotics can be used as a supplement or alternative to paroxetine in patients with generalised anxiety disorder.[2]

Although the evidence is conflicting, paroxetine may be effective for the treatment of dysthymia, a chronic disorder which involves depressive symptoms for most days of the year.[30]

Efficacy

According to the prescribing information provided by the manufacturer of the Paxil brand of paroxetine (GlaxoSmithKline) and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA),[31] the effectiveness of paroxetine in major depressive disorder has been proven by six placebo-controlled clinical trials. In adults, the efficacy of paroxetine for depression is comparable to that of older tricyclic antidepressants.[5][32] A randomized-trial study showed that paroxetine is more effective for treatment of major depression than placebo also specifically in elderly patients.[33]

For panic disorder, three 10-12-week studies indicated paroxetine superiority to placebo.[31]

For social anxiety disorder, three 12-week trials for adult outpatients demonstrated better response to paroxetine than to placebo.[31]

Adverse effects

Sexual dysfunction is a common side effect with SSRIs. Specifically, side effects often include difficulty becoming aroused, lack of interest in sex, and anorgasmia (trouble achieving orgasm). Genital anesthesia,[34] loss of or decreased response to sexual stimuli, and ejaculatory anhedonia are also possible. Although usually reversible, these sexual side effects can last for months or years after the drug has been completely withdrawn.[35] This is known as post SSRI sexual dysfunction.

Among the common adverse effects associated with paroxetine treatment of depression and listed in the prescribing information, those with the greatest difference from placebo are nausea (26% on paroxetine vs 9% on placebo), somnolence (23% vs. 9% on placebo), ejaculatory disturbance (13% vs. 0% on placebo), other male genital disorders (10% vs. 0% on placebo), asthenia (15% vs. 6% on placebo), sweating (11% vs. 2% on placebo), dizziness (13% vs. 6% on placebo), insomnia (13% vs. 6% on placebo), dry mouth (18% vs. 12% on placebo), constipation (14% vs. 9% on placebo), and tremor (8% vs. 2% on placebo).[31] Other side effects include high blood pressure, headache, agitation, weight gain, impaired memory and paresthesia, decreased fertility.[36]

General side effects are mostly present during the first 1–4 weeks while the body acquires a tolerance to the drug, although once this happens, withdrawal can cause a rebound effect with symptoms re-emerging in an exaggerated form for very long periods of time. Almost all SSRIs are known to cause either one or more of these symptoms. A person receiving paroxetine treatment may experience a few, all, or none of the listed side-effects, and most side-effects will disappear or lessen with continued treatment, though some may last throughout the duration. Side effects are also often dose-dependent, with fewer and/or less severe symptoms being reported at lower dosages, and/or more severe symptoms being reported at higher dosages. Increases or changes in dosage may also cause symptoms to reappear or worsen.[31]

On 9 December 2004, the European Medicines Agency's (EMEA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) informed patients, prescribers, and parents that paroxetine should not be prescribed to children. CHMP also gave a warning to prescribers recommending close monitoring of adult patients at high risk of suicidal behaviour and/or suicidal thoughts. CHMP does not prohibit use of paroxetine with high risk adults but urges extreme caution. Due to reports of adverse withdrawal reactions upon terminating treatment, CHMP recommends to reduce gradually over several weeks or months if the decision to withdraw is made.[37] See also Discontinuation syndrome (withdrawal).

Cases of akathisia[38][39] and activation syndrome[40][41] have been observed during paroxetine treatment.

Rarely serotonin syndrome, a severe adverse effect may occur.[42][43]

Paroxetine and other SSRIs have been shown to cause sexual side effects in most patients, both males and females.[44] In males, paroxetine is also linked to sperm DNA fragmentation.[45]

Mania or hypomania may occur as a serious side effect of paroxetine,[46][47][48] affecting up to 8% of psychiatric patients treated. This side effect can occur in individuals with no history of mania but it is more likely to occur in those with bipolar or with a family history of mania.[49]

Schmitt et al. (2001) suggested that paroxetine negatively affects long-term memory, but not short-term, although the result has not been independently verified. In their study, healthy participants given paroxetine for 14 days (20 mg for days 1–7 and 40 mg days 8–14) showed poorer recall of words on day 14 compared to those receiving a placebo.[50] Schmitt et al. did not take into account a significant difference in verbal recall at baseline between the paroxetine and placebo groups, however, and this difference may have been the source of the significant group difference on day 14.[original research?] Moreover, participants receiving paroxetine recalled as many words at baseline as they recalled on day 14, which is not consistent with the conclusion that paroxetine negatively affects verbal recall.[original research?]

Contraindications

Paroxetine is contraindicated in all patients under 18, in all patients taking any of the drugs listed in the interactions section below, and in adult women who are or may become pregnant. Paroxetine may also be contraindicated in many adult men due to sexual and reproductive side effects described below. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration requires this drug to carry a black box warning, its "most serious type of warning in prescription drug labeling,"[51] due to increased risk of suicidal ideation and behavior. The warning also applies to other SSRIs, but the concern began with reports of suicidal behavior in paroxetine trials, as well as recommendations from the United Kingdom Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency urging that paroxetine not be used in individuals younger than 18 years.[52]

Suicidality

Paroxetine may increase the risk of suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior in children and adolescents. Because suicide is rare, it is difficult to test the relationship between Paroxetine and suicide. Some studies instead analyze suicidality, which generally refers to suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior. The FDA conducted a statistical analysis of paroxetine clinical trials in children and adolescents in 2004, finding an increase in "suicidality" and ideation as compared to placebo; the trend for increased "suicidality" was observed in both trials for depression and for anxiety disorders.[8] A University of North Carolina review of SSRIs found the average risk of suicide among adolescents was 4%, versus 2% on placebo, and among all patients "the greatest risk of self-harm was among paroxetine users."[53]

Discontinuation syndrome

Many psychoactive medications can cause withdrawal symptoms upon discontinuation from administration. Evidence has shown that paroxetine has among the highest incidence rates and severity of withdrawal syndrome of any medication of its class.[54] Common withdrawal symptoms for paroxetine include nausea, dizziness, lightheadedness and vertigo; insomnia, nightmares and vivid dreams; feelings of electricity in the body, as well as crying and anxiety.[55][56] Liquid formulation of paroxetine is available and allows a very gradual decrease of the dose, which may prevent discontinuation syndrome. Another recommendation is to temporarily switch to fluoxetine, which has a longer half-life and thus decreases the severity of discontinuation syndrome.[11][57][58]

In addition, The Lancet published an analysis of World Health Organization data showing SSRIs taken during pregnancy may cause withdrawal symptoms, including convulsions, in newborn children: among "93 suspected cases of SSRI-induced neonatal withdrawal syndrome...64 were associated with paroxetine, 14 with fluoxetine, nine with sertraline, and seven with citalopram."[59]

Paroxetine and pregnancy

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that for pregnant women and women planning to become pregnant, "treatment with all SSRIs or selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors or both during pregnancy be individualized and paroxetine use among pregnant women or women planning to become pregnant be avoided, if possible."[13] According to the prescribing information[31] "epidemiological studies have shown that infants born to women who had first trimester paroxetine exposure had an increased risk of cardiovascular malformations, primarily ventricular and atrial septal defects (VSDs and ASDs). In general, septal defects range from those that are symptomatic and may require surgery to those that are asymptomatic and may resolve spontaneously. If a patient becomes pregnant while taking paroxetine, she should be advised of the potential harm to the fetus. Unless the benefits of paroxetine to the mother justify continuing treatment, consideration should be given to either discontinuing paroxetine therapy or switching to another antidepressant. For women who intend to become pregnant or are in their first trimester of pregnancy, paroxetine should only be initiated after consideration of the other available treatment options." These conclusions are supported by multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses that found that, on average, the use of paroxetine during pregnancy is associated with about 1.5-1.7-fold increase in congenital birth defects, in particular, heart defects.[60][61][62][63][64] A recent non-systematic review in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, with the lead author, Salvatore Gentile, reporting to have received material or financial support from GSK, came to a different conclusion: "the teratogenic potential of paroxetine that has been reported in some studies remains unproven." Gentile called for large, epidemiologic, prospective, controlled studies on "mothers who accept taking paroxetine during pregnancy".[65] Other reviews vary on whether the teratogenic risks outweigh the risk of disease relapse if the drug is discontinued: some advocate discontinuation,[60] while others suggest caution;[62] even where the overview of antidepressants generally is favorable, paroxetine is singled out for specific risks.[63] Paroxetine use during pregnancy increases the risk of spontaneous abortion.[66][67]

A large 2010 study — using the Swedish Medical Birth Register (MBR) from 1 July 1995 up to 2007 identified women who reported the use of antidepressants in early pregnancy or were prescribed antidepressants during pregnancy by antenatal care — found a specific association between Paxil use and infant cardiovascular defects.[68] A strong association between Paxil and hypospadias was also concluded in this study, though the researchers concluded that it is not clear if these effects were due to drug use or underlying pathology.[68]

Abrupt discontinuation of psychotropic drugs during pregnancy can also lead to serious adverse effects.[69]

Counseling is effective in reassuring women to adhere to therapy,[69] but neonatal paroxetine withdrawal symptoms described above have been documented from mothers taking Paxil during pregnancy.[70]

Interactions

GlaxoSmithKline cautions that drug interactions may create or increase specific risks, including Serotonin Syndrome or Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS)-like Reactions:

- The development of a potentially life-threatening serotonin syndrome or Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS)-like reactions have been reported with SNRIs and SSRIs alone, including treatment with PAXIL, but particularly with concomitant use of serotonergic drugs (including triptans) with drugs which impair metabolism of serotonin (including MAOIs), or with antipsychotics or other dopamine antagonists.

The prescribing information states that paroxetine should "not be used in combination with an MAOI (including linezolid, an antibiotic which is a reversible non-selective MAOI), or within 14 days of discontinuing treatment with an MAOI," and should not be used in combination with pimozide, thioridazine, tryptophan, or warfarin.[71]

Paroxetine is metabolized by cytochrome P450 2D6. The breast cancer treatment drug tamoxifen is also metabolized to its active state by the same cytochrome. Patients treated with both paroxetine and tamoxifen have an increased risk of death from breast cancer from 24% to 91%, depending on duration of coexposure.[72]

Overdosage

Acute overdosage is often manifested by emesis, lethargy, ataxia, tachycardia and seizures. Plasma, serum or blood concentrations of paroxetine may be measured to monitor therapeutic administration, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to aid in the medicolegal investigation of fatalities. Plasma paroxetine concentrations are generally in a range of 40-400 μg/L in persons receiving daily therapeutic doses and 200-2000 μg/L in poisoned patients. Postmortem blood levels have ranged from 1–4 mg/L in acute lethal overdose situations.[73][74]

Pharmacology

Paroxetine is the most potent and one of the most specific selective serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) reuptake inhibitors (SSRI).[75] This activity of the drug on brain neurons is thought to be responsible for its antidepressant effects.

Paroxetine is a phenylpiperidine derivative which is chemically unrelated to the tricyclic or tetracyclic antidepressants. In receptor binding studies, paroxetine did not exhibit significant affinity for the adrenergic (α1, α2, β), dopaminergic, serotonergic (5HT1, 5HT2), or histamine receptors of rat brain membrane.[citation needed] A weak affinity for the muscarinic acetylcholine and noradrenaline receptors was evident.[citation needed] The predominant metabolites of paroxetine are approximately 1/50th the strength of paroxetine and are essentially inactive.[citation needed]

Paroxetine has been shown to have antimicrobial activity against several groups of microorganisms. This is mainly against Gram positive microorganisms. It also shows synergistic activity when combined with some antibiotics against several bacteria.[76] Paroxetine has also been demonstrated to have antifungal activity being most potent against the hypersusceptible Candida albicans strain DSY1204.[77]

Formulations

Paroxetine CR (controlled release) was shown to be associated with a lower rate of nausea during the first week of treatment than paroxetine immediate release. However, the rate of treatment discontinuation due to nausea was not significantly different.[78]

Society and culture

Controversy

For 10 years, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) marketing of the drug stated that it was "not habit forming," which numerous experts and at least one court found to be incorrect.[79][80][81] In 2001, the BBC reported the World Health Organization had ranked paroxetine as the most difficult antidepressant to withdraw from. In 2002, the U.S. FDA published a new product warning about the drug, and the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Associations said GSK had misled the public about paroxetine and breached two of the Federation's codes of practice.[82] The British Medical Journal quoted Charles Medawar, head of Social Audit: "This drug has been promoted for years as safe and easy to discontinue.... The fact that it can cause intolerable withdrawal symptoms of the kind that could lead to dependence is enormously important to patients, doctors, investors, and the company. GlaxoSmithKline has evaded the issue since it was granted a license for paroxetine over 10 years ago, and the drug has become a blockbuster for them, generating about a tenth of their entire revenue. The company has been promoting paroxetine directly to consumers as 'non-habit forming' for far too long." Paroxetine prescribing information posted at GlaxoSmithKline now acknowledges the occurrence of a discontinuation syndrome, including serious discontinuation symptoms.[83]

Since the FDA approved paroxetine in 1992, approximately 5,000 U.S. citizens have sued GSK. Most of these people feel they were not sufficiently warned in advance of the drug's side effects—particularly the withdrawal syndrome discussed above, after GSK had specifically advertised the drug as non-habit forming.

In 2001, GSK increased its American TV advertising of Paxil after the September 11 attacks; in October 2001, GSK spent nearly twice as much as in October 2000.[84] The difficulty of withdrawal from paroxetine, and GSK's concealment of it, was later reported on ABC.[85]

Since 2001 in the UK, lawsuits have been filed representing people who have been prescribed Seroxat. They allege that the drug has serious side effects, which GlaxoSmithKline downplayed in patient information.[86][87]

In early 2004, GSK agreed to settle charges of consumer fraud for $2.5 million (a tiny fraction of the over $2.7 billion in yearly Paxil sales at that time).[88] The legal discovery process also uncovered evidence of deliberate, systematic suppression of unfavorable Paxil research results. One of GSK's internal documents had said, "It would be commercially unacceptable to include a statement that efficacy [in children] had not been demonstrated, as this would undermine the profile of paroxetine".[89]

In June 2004, FDA published a violation letter to GSK in response to a "false or misleading" TV ad for Paxil CR; FDA stated, "This ad is concerning from a public health perspective because it broadens the use of Paxil CR [beyond the conditions it was approved for] while also minimizing the serious risks associated with the drug."[90] GSK claimed the ad had been previously reviewed by FDA, but said the ad would not run again.[91]

On January 29, 2007, the BBC broadcast a fourth documentary in its Panorama series about the drug Seroxat.[92] This programme, entitled "Secrets of the Drug Trials", focused on three GSK paediatric clinical trials on depressed children and adolescents. Data from the trials show that Seroxat could not be proven to work for teenagers. Also, one clinical trial indicated that adolescents were six times more likely to become suicidal after taking it. Results from Study 329, one of the trials, were reported[93] in a way which misled readers about paroxetine's safety and efficacy, and contributed to repeated distortions in the assessment of the drug's value in paediatric depression in the scientific literature.[94][unreliable source?]

The court documents released as a result of one of the lawsuits in October 2008 indicated that GSK "and/or researchers may have suppressed or obscured suicide risk data during clinical trials" of paroxetine. One of the investigators, "Charles Nemeroff, former chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at Emory University, was the first big name 'outed' ...In early October 2008, Nemeroff stepped down as department chair amid revelations that he had received over $960,000 from GSK in 2006, yet reported less than $35,000 to the school. Subsequent investigations revealed payments totaling more than $2.5 million from drug companies between 2000 and 2006, yet only a fraction was disclosed."[95]

The suppression of unfavorable research findings on Paxil by GSK — and the legal discovery process that uncovered it — is the subject of Alison Bass's 2008 book Side Effects: A Prosecutor, a Whistleblower, and a Bestselling Antidepressant on Trial. The book chronicles the lives of two women - a prosecutor and a whistleblower - who exposed deception in the research and marketing of Paxil. The book shows the connections between pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline, a top Ivy League research institution, and the government agency designed to protect the public - conflicted relationships that arguably compromised the health and safety of vulnerable children. Side Effects received the NASW Science in Society Award for 2009.[96][97]

In 2012 the U.S. Justice Department announced that GSK had agreed to plead guilty and pay a $3 billion fine, in part for promoting the use of Paxil for children.[98]

Sales

In 2007, paroxetine was ranked 94th on the list of bestselling drugs, with over $1 billion in sales. In 2006, paroxetine was the fifth-most prescribed antidepressant in the United States retail market, with more than 19.7 million prescriptions.[99] In 2007, sales had dropped slightly to 18.1 million but paroxetine remained the fifth-most prescribed antidepressant in the U.S.[100]

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ a b Katzman MA (2009). "Current considerations in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder". CNS Drugs. 23 (2): 103–20. doi:10.2165/00023210-200923020-00002. PMID 19173371.

- ^ "New profit twist for drugmakers". CNN Money. May 11, 2005.

- ^ "GlaxoSmithKline to pay $3bn in US drug fraud scandal". BBC News. July 02, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Anderson IM (2000). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability". J Affect Disord. 58 (1): 19–36. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(99)00092-0. PMID 10760555.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Montgomery SA. (2001). "A meta-analysis of the efficacy and tolerability of paroxetine versus tricyclic antidepressants in the treatment of major depression". International clinical psychopharmacology. 16 (3): 169–78. doi:10.1097/00004850-200105000-00006. PMID 11354239.

- ^ Papakostas GI (2008). "Tolerability of modern antidepressants". J Clin Psychiatry. 69 (Suppl E1): 8–13. PMID 18494538.

- ^ a b Hammad TA (2004-08-16). "Review and evaluation of clinical data: relationship between psychotropic drugs and pediatric suicidality" (PDF). Joint Meeting of the Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee and Pediatric Advisory Committee. September 13–14, 2004. Briefing Information. FDA. p. 30. Retrieved 2009-01-27.

- ^ Hammad TA, Laughren T, Racoosin J (2006). "Suicidality in pediatric patients treated with antidepressant drugs". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 63 (3): 332–9. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.332. PMID 16520440.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Report of the CSM expert working group on the safety of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants" (PDF). MHRA. 2004-12. Retrieved 2009-02-17.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Haddad P (2001). "Antidepressant discontinuation syndromes". Drug Saf. 24 (3): 183–97. doi:10.2165/00002018-200124030-00003. PMID 11347722.

- ^ Tonks A (2002). "Withdrawal from paroxetine can be severe, warns FDA". BMJ. 324 (7332): 260. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7332.260. PMC 1122195. PMID 11823353.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice (2006). "ACOG Committee Opinion No. 354: Treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy". Obstet Gynecol. 108 (6): 1601–3. PMID 17138801.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "FDA Public Health Advisory Paroxetine". Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 05/02/2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) [dead link] - ^ "Paroxetine and Pregnancy". GlaxoSmithKline. Retrieved 05/02/2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Yonkers, KA; Wisner, KL; Stewart, DE; Oberlander, TF; Dell, DL; Stotland, N; Ramin, S; Chaudron, L; Lockwood, C (2009). "The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists". Obstetrics and gynecology. 114 (3): 703–13. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ba0632. PMID 19701065.

- ^ Use of Paxil CR Tablets or Paxil Tablets During Pregnancy

- ^ Baldwin DS, Anderson IM, Nutt DJ, Bandelow B, Bond A, Davidson JR, den Boer JA, Fineberg NA, Knapp M, Scott J, Wittchen HU (2005). "Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 19 (6): 567–596. doi:10.1177/0269881105059253. PMID 16272179.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ D Baldwin, J Bobes, DJ Stein, I Scharwachter and M Faure (1999). "Paroxetine in social phobia/social anxiety disorder. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Paroxetine Study Group". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 175 (2): 120–6. doi:10.1192/bjp.175.2.120. PMID 10627793.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yonkers KA, Gullion C, Williams A, Novak K, Rush AJ. (1996). "Paroxetine as a treatment for premenstrual dysphoric disorder". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 16 (1): 3–8. doi:10.1097/00004714-199602000-00002. PMID 8834412.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Turner, Francis Joseph (2005). Social Work Diagnosis in Contemporary Practice. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0-19-516878-X.

- ^ Waldinger MD, Hengeveld MW, Zwinderman AH, Olivier B (1998). "Effect of SSRI antidepressants on ejaculation: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study with fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and sertraline". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 18 (4): 274–81. doi:10.1097/00004714-199808000-00004. PMID 9690692.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Waldinger MD, Zwinderman AH, Olivier B (2001). "SSRIs and ejaculation: a double-blind, randomized, fixed-dose study with paroxetine and citalopram". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 21 (6): 556–60. doi:10.1097/00004714-200112000-00003. PMID 11763001.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Waldinger MD, Zwinderman AH, Olivier B (2004). "On-demand treatment of premature ejaculation with clomipramine and paroxetine: a randomized, double-blind fixed-dose study with stopwatch assessment". Eur. Urol. 46 (4): 510–5, discussion 516. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2004.05.005. PMID 15363569.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brown J, O' Brien PM, Marjoribanks J, Wyatt K (2009). Brown, Julie (ed.). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD001396. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001396.pub2. PMID 19370564.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kim SW, Grant JE, Adson DE, Shin YC, Zaninelli R (2002). "A double-blind placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of paroxetine in the treatment of pathological gambling". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 63 (6): 501–7. doi:10.4088/JCP.v63n0606. PMID 12088161.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Weitzner MA, Moncello J, Jacobsen PB, Minton S. (2002). "A pilot trial of paroxetine for the treatment of hot flashes and associated symptoms in women with breast cancer". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 23 (4): 337–345. doi:10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00379-2. PMID 11997203.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, Goikolea JM, Torrent C, Colom F, Benabarre A, Reinares M (1999). "The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine is effective in the treatment of diabetic neuropathy symptoms". Pain. 42 (2): 135–144. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(90)91157-E. PMID 2147235.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Langemark M, Olesen J (1994). "Sulpiride and paroxetine in the treatment of chronic tension-type headache. An explanatory double-blind trial". Headache. 34 (1): 20–4. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1994.hed3401020.x. PMID 8132436.

- ^ Gartlehner G, Gaynes BN, Hansen RA; et al. (2008). "Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants: background paper for the American College of Physicians". Ann. Intern. Med. 149 (10): 734–50. PMID 19017592.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f "PAXIL (paroxetine hydrochloride) Tablets and Oral Suspension: PRESCRIBING INFORMATION" (PDF). Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ {{broken ref

|prefix=Cite error: The named reference

{

Unexpected use of template {{1}} - see Template:1 for details. (see the help page). - ^ Rapaport MH, Schneider LS, Dunner DL, Davies JT, Pitts CD (2003). "Efficacy of controlled-release paroxetine in the treatment of late-life depression" (PDF). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 64 (9): 1065–74. doi:10.4088/JCP.v64n0912. PMID 14628982.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bolton JM, Sareen J, Reiss JP (2006). "Genital anaesthesia persisting six years after sertraline discontinuation". J Sex Marital Ther. 32 (4): 327–30. doi:10.1080/00926230600666410. PMID 16709553.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Csoka AB, Bahrick AS, Mehtonen O-P (2008). "Persistent Sexual Dysfunction after Discontinuation of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs)". J Sex Med. 5 (1): 227–33. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00630.x. PMID 18173768.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Masand PS, Gupta S (1999). "Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors: an update". Harv Rev Psychiatry. 7 (2): 69–84. doi:10.1093/hrp/7.2.69. PMID 10471245.

- ^ "Press release, CHMP meeting on Paroxetine and other SSRIs" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 2004-12-09. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ^ Olivera AA (1996). "A case of paroxetine-induced akathisia". Biol. Psychiatry. 39 (10): 910. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(96)84504-5. PMID 8860197.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Baldassano CF, Truman CJ, Nierenberg A, Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS (1996). "Akathisia: a review and case report following paroxetine treatment". Compr Psychiatry. 37 (2): 122–4. doi:10.1016/S0010-440X(96)90572-6. PMID 8654061.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Important Safety Information about Paxil CR". GlaxoSmithKline.

- ^ Nishida T, Wada M, Wada M, Ito H, Narabayashi M, Onishi H (2008). "Activation syndrome caused by paroxetine in a cancer patient". Palliat Support Care. 6 (2): 183–5. doi:10.1017/S1478951508000278. PMID 18501054.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ochiai Y, Katsu H, Okino S, Wakutsu N, Nakayama K (2003). "[Case of prolonged recovery from serotonin syndrome caused by paroxetine]". Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi (in Japanese). 105 (12): 1532–8. PMID 15027311.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Terao T, Hikichi T (2007). "Serotonin syndrome in a case of depression with various somatic symptoms: the difficulty in differential diagnosis". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 31 (1): 295–6. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.07.007. PMID 16916568.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Clayton, A (2006). "Burden of phase-specific sexual dysfunction with SSRIs". Journal of Affective Disorders. 91 (1): 27–32. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.007. PMID 16430968.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wachter, Kerri (2009). "Paroxetine linked to sperm DNA fragmentation". Internal Medicine News.

- ^ Vesely C, Fischer P, Goessler R, Kasper S (1997). "Mania associated with serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors". J Clin Psychiatry. 58 (2): 88. doi:10.4088/JCP.v58n0206e. PMID 9062382.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ramasubbu R (2004). "Antidepressant treatment-associated behavioural expression of hypomania: a case series". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 28 (7): 1201–7. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.06.015. PMID 15610935.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Grubbs JH (1997). "SSRI-induced mania". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 36 (4): 445. doi:10.1097/00004583-199704000-00003. PMID 9100415.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Morishita S, Arita S (2003). "Induction of mania in depression by paroxetine". Hum Psychopharmacol. 18 (7): 565–8. doi:10.1002/hup.531. PMID 14533140.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Schmitt JA, Kruizinga MJ, Riedel WJ (2001). "Non-serotonergic pharmacological profiles and associated cognitive effects of serotonin reuptake inhibitors". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford). 15 (3): 173–9. doi:10.1177/026988110101500304. PMID 11565624.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Medications for Children and Adolescents: Information for Parents and Caregivers, National Institute of Mental Health

- ^ Black Box Warnings Incite Red Flags, Pharmacy Times, May 1, 2008

- ^ Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Kahwati L, Lohr KN, Gaynes B, Carey T (March 2006). "Drug Class Review on Second Generation Antidepressants: Final Report". Drug Class Reviews. Portland OR: Oregon Health & Science University. PMID 20480925. NBK10326.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Anti-depressant addiction warning". BBC News. 2001-06-11. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ^ Skaehill, Penny A. (1997). "Clinical Reviews: SSRI Withdrawal Syndrome". American Society of Consultant Pharmacists. Retrieved 2007-08-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bhanji NH, Chouinard G, Kolivakis T, Margolese HC (2006). "Persistent tardive rebound panic disorder, rebound anxiety and insomnia following paroxetine withdrawal: a review of rebound-withdrawal phenomena" (PDF). Can J Clin Pharmacol. 13 (1): e69–74. PMID 16456219.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Haddad PM, Anderson IM (November 2007). "Recognising and managing antidepressant discontinuation symptoms". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 13 (6): 447–457. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.105.001966.

- ^ http://www.benzo.org.uk/healy.htm

- ^ http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/498763

- ^ a b Thormahlen GM (2006). "Paroxetine use during pregnancy: is it safe?". Ann Pharmacother. 40 (10): 1834–7. doi:10.1345/aph.1H116. PMID 16926304.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Way CM (2007). "Safety of newer antidepressants in pregnancy". Pharmacotherapy. 27 (4): 546–52. doi:10.1592/phco.27.4.546. PMID 17381382.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Bellantuono C, Migliarese G, Gentile S (2007). "Serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and the risk of major malformations: a systematic review". Hum Psychopharmacol. 22 (3): 121–8. doi:10.1002/hup.836. PMID 17397101.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Källén B (2007). "The safety of antidepressant drugs during pregnancy". Expert Opin Drug Saf. 6 (4): 357–70. doi:10.1517/14740338.6.4.357. PMID 17688379.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bar-Oz B, Einarson T, Einarson A; et al. (2007). "Paroxetine and congenital malformations: meta-Analysis and consideration of potential confounding factors". Clin Ther. 29 (5): 918–26. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.05.003. PMID 17697910.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gentile S, Bellantuono C (2009). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure during early pregnancy and the risk of fetal major malformations: focus on paroxetine". J Clin Psychiatry. 70 (3): 414–22. doi:10.4088/JCP.08r04468. PMID 19254517.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19863482, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19863482instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 20513781, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=20513781instead. - ^ a b Reis M, Kallen B (2010). "Delivery outcome after maternal use of antidepressant drugs in pregnancy: an update using Swedish data". Psychological Medicine. 40 (10): 1723–33. doi:10.1017/S0033291709992194. PMID 20047705.

- ^ a b Einarson A, Selby P, Koren G (2001). "Abrupt discontinuation of psychotropic drugs during pregnancy: fear of teratogenic risk and impact of counselling" (PDF). J Psychiatry Neurosci. 26 (1): 44–8. PMC 1408034. PMID 11212593.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Haddad PM, Pal BR, Clarke P, Wieck A, Sridhiran S (2005). "Neonatal symptoms following maternal paroxetine treatment: serotonin toxicity or paroxetine discontinuation syndrome?". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford). 19 (5): 554–7. doi:10.1177/0269881105056554. PMID 16166193.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://us.gsk.com/products/assets/us_paxil.pdf

- ^ Kelly CM, Juurlink DN, Gomes T; et al. (2010). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and breast cancer mortality in women receiving tamoxifen: a population based cohort study". BMJ. 340: c693. PMC 2817754. PMID 20142325.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Goeringer KE, Raymon L, Christian GD, Logan BK (2000). "Postmortem forensic toxicology of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a review of pharmacology and report of 168 cases". J. Forensic Sci. 45 (3): 633–48. PMID 10855970.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 1190-1193.

- ^ Mellerup, Erling T. (1986). "High affinity binding of3H-paroxetine and3H-imipramine to rat neuronal membranes". Psychopharmacology. 89 (4): 436–9. doi:10.1007/BF02412117. PMID 2944152.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Munoz-Bellido JL, Munoz-Criado S, Garcìa-Rodrìguez JA (2000). "Antimicrobial activity of psychotropic drugs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors". Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 14 (3): 177–80. doi:10.1016/S0924-8579(99)00154-5. PMID 10773485.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Young TJ, Oliver GP, Pryde D, Perros M, Parkinson T (2003). "Antifungal activity of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors attributed to non-specific cytotoxicity". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51 (4): 1045–7. doi:10.1093/jac/dkg184. PMID 12654745.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Golden RN, Nemeroff CB, McSorley P, Pitts CD, Dube EM. (2002). "Efficacy and tolerability of controlled-release and immediate-release paroxetine in the treatment of depression". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 63 (7): 577–584. doi:10.4088/JCP.v63n0707. PMID 12143913.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Judge: Paxil ads can't say it isn't habit-forming". USA Today. 2002-08-20. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ^ http://www.socialaudit.org.uk/4606-BAUM%20HEDLUND.htm

- ^ Paxil is Forever, City Pages, Oct 16 2002

- ^ "HOT flashes". Friend Indeed, A. 2002.

- ^ Paxil (paroxetine hydrochloride) prescribing information

- ^ "Drug Makers Find Sept. 11 A Marketing Opportunity". Psychiatric News. 1 March 2001. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

- ^ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xSUAsdBgh70

- ^ Garfield, Simon (2002-04-29). "The Chemistry of Happiness". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- ^ Stayton, Jonathan (2008-01-22). "Punk rocker sues over anti-depressant". The Argus. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ^ Angell M (15 January 2009). "Drug Companies & Doctors: A Story of Corruption". New York Review of Books. Vol. 56, no. 1.

- ^ Kondro W, Sibbald B (2004). "Drug company experts advised staff to withhold data about SSRI use in children". CMAJ. 170 (5): 783. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1040213. PMC 343848. PMID 14993169.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ FDA Warning Letter

- ^ "Company News; F.D.A. Asks Glaxosmithkline To Stop Running A Paxil Ad". The New York Times. 2004-06-12. Retrieved 2010-03-27.

- ^ "Secrets of the drug trials". BBC. 2007-01-29. Retrieved 2007-08-15.

- ^ Keller MB; et al. (2001). "Efficacy of paroxetine in the treatment of adolescent major depression: a randomized, controlled trial". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 40 (7): 762–72. doi:10.1097/00004583-200107000-00010. PMID 11437014.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Paxil Study 329: Paroxetine vs Imipramine vs Placebo in Adolescents, Healthy Skepticism International News, January 2010

- ^ Samson K (2008). "Senate probe seeks industry payment data on individual academic researchers". Ann. Neurol. 64 (6): A7–9. doi:10.1002/ana.21271. PMID 19107985.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.nasw.org/mt-archives/2009/09/scienceinsociety-journalism-aw-1.htm

- ^ Bass, Alison (2008), Side Effects: A Prosecutor, a Whistleblower, and a Bestselling Antidepressant on Trial, Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

- ^ "Glaxo Agrees to Pay $3 Billion in Fraud Settlement". The New York Times. July 2, 2012.

- ^ The paroxetine prescriptions were calculated as a total of prescriptions for Paxil CR and generic paroxetine using data from the charts for generic and brand-name drugs."Top 200 generic drugs by units in 2006. Top 200 brand-name drugs by units". Drug Topics, Mar 5, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-08.

- ^ The paroxetine prescriptions were calculated as a total of prescriptions for Paxil CR and generic paroxetine using data from the charts for generic and brand-name drugs."Top 200 generic drugs by units in 2007". Drug Topics, Feb 18, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-23. "Top 200 brand drugs by units in 2007". Drug Topics, Feb 18, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paroxetine.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paroxetine.

- List of international brand names for paroxetine

- Detailed Paroxetine Consumer Information: Uses, Precautions, Side Effects from medlibrary.org

- The Secrets of Seroxat, BBC Panorama investigation

- Antidepressant Use in Children Soars Despite Efficacy Doubts, Washington Post, April 18, 2004

- Healthy Skepticism's repository and analysis of GSK documents related to Study 329