Anti-nuclear movement in Australia: Difference between revisions

→2010s: ce |

|||

| Line 88: | Line 88: | ||

In March 2012, hundreds of anti-nuclear demonstrators converged on the Australian headquarters of global mining giants BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto. The 500-strong march through southern Melbourne called for an end to uranium mining in Australia, and included speeches and performances by representatives of the expatriate Japanese community as well as Australia's Indigenous communities, who are concerned about the effects of uranium mining near tribal lands. There were also events in Sydney.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.voanews.com/english/news/asia/east-pacific/Australian-Rallies-Remember-Fukushima-Disaster-142242575.html |title= Australian Rallies Remember Fukushima Disaster |author=Phil Mercer |date=March 11, 2012 |work=VOA News }}</ref> |

In March 2012, hundreds of anti-nuclear demonstrators converged on the Australian headquarters of global mining giants BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto. The 500-strong march through southern Melbourne called for an end to uranium mining in Australia, and included speeches and performances by representatives of the expatriate Japanese community as well as Australia's Indigenous communities, who are concerned about the effects of uranium mining near tribal lands. There were also events in Sydney.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.voanews.com/english/news/asia/east-pacific/Australian-Rallies-Remember-Fukushima-Disaster-142242575.html |title= Australian Rallies Remember Fukushima Disaster |author=Phil Mercer |date=March 11, 2012 |work=VOA News }}</ref> |

||

A site within [[Muckaty Station]] is being considered for Australia's [[Low level waste|low-level]] and intermediate-level [[radioactive waste]] storage and disposal facility. However, the plan is subject to a Federal Court challenge due to be heard early in 2013. |

|||

==Ban on nuclear reactors== |

==Ban on nuclear reactors== |

||

Revision as of 23:16, 26 June 2012

Nuclear testing, uranium mining and export, and nuclear energy have often been the subject of public debate in Australia, and the anti-nuclear movement in Australia has a long history. Its origins date back to the 1972–73 debate over French nuclear testing in the Pacific and the 1976–77 debate about uranium mining in Australia.[1][2]

Several groups specifically concerned with nuclear issues were established in the mid-1970s, including the Movement Against Uranium Mining and Campaign Against Nuclear Energy (CANE), cooperating with other environmental groups such as Friends of the Earth and the Australian Conservation Foundation.[3][4] The movement suffered a setback in 1983 when the newly elected Labor Government failed to implement its stated policy of stopping uranium mining.[5] But by the late 1980s, the price of uranium had fallen, the costs of nuclear power had risen, and the anti-nuclear movement seemed to have won its case; CANE was disbanded in 1988.[6]

About 2003, proponents of nuclear power advocated it as a solution to global warming and the Australian government began taking an interest. Anti-nuclear campaigners and some scientists in Australia argued that nuclear power could not significantly substitute for other power sources, and that uranium mining itself could become a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions.[7][8]

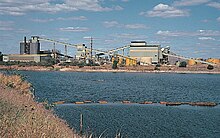

As of 2010, Australia has no nuclear power stations and the current Gillard Labor government is opposed to nuclear power for Australia.[9] Australia has three operating uranium mines at Olympic Dam (Roxby) and Beverley – both in South Australia's north – and at Ranger in the Northern Territory. As of April 2009, construction has begun on South Australia's third uranium mine—the Honeymoon Uranium Mine.[10] Australia has no nuclear weapons.

History

1950s and 1960s

In 1952 the Australian Government established the Rum Jungle Uranium Mine 85 kilometres south of Darwin. Local aboriginal communities were not consulted and the mine site became an environmental disaster.[11]

Also in 1952, the Robert Menzies Liberal Government passed legislation, the "Defence (Special Undertakings) Act 1952", which allowed the British Government access to isolated parts of Australia to undertake atmospheric nuclear tests. These tests were mainly conducted at Maralinga in South Australia between 1955 and 1963, but the full legal and political implications of the testing program took decades to emerge. The secrecy which surrounded the British testing program and the remoteness of the test sites meant that public awareness of the risks involved grew very slowly.[12]

But as the "Ban the Bomb" movement gathered momentum in Western societies throughout the 1950s, so too did opposition to the British tests in Australia. An opinion poll taken in 1957 showed 49 per cent of the Australian public were opposed to the tests and only 39 per cent in favour.[12] In 1964, Peace Marches which featured "Ban the bomb" placards, were held in several Australian capital cities.[13][14]

In 1969, a 500 MW nuclear power plant was proposed for the Jervis Bay Territory, 200 km south of Sydney.[3] A local opposition campaign began, and the South Coast Trades and Labour Council (covering workers in the region) announced that it would refuse to build the reactor.[15] Some environmental studies and site works were completed, and two rounds of tenders were called and evaluated, but in 1971 the Australian government decided not to proceed with the project, citing economic reasons.[3][16]

1970s

The 1972–73 debate over French nuclear testing in the Pacific mobilised several groups, including some trade unions.[17] In 1972 the International Court of Justice in a case launched by Australia and New Zealand, ordered that the French cease atmospheric nuclear testing at Mururoa atoll.[18] In 1974 and 1975 this concern came to focus on uranium mining in Australia and several Friends of the Earth groups were formed.[17] The Australian Conservation Foundation also began voicing concern about uranium mining and supporting the activities of the grass-roots organisations. Concern about the environmental effects of uranium mining was a significant factor and poor management of waste at an early uranium mine, Rum Jungle, led it to become a significant pollution problem in the 1970s.[17] The Australian anti-nuclear movement also acquired initial impetus from notable individuals who publicly voiced nuclear concerns, such as nuclear scientists Richard Temple and Rob Robotham, and poets Dorothy Green and Judith Wright.[17]

The years 1976 and 1977 saw uranium mining become a major political issue, with the Ranger Inquiry (Fox) report opening up a public debate about uranium mining.[19] Several groups specifically concerned with nuclear issues were established, including the Movement Against Uranium Mining (founded in 1976) and Campaign Against Nuclear Energy (formed in South Australia in 1976), cooperating with other environmental groups such as Friends of the Earth (which came to Australia in 1975) and the Australian Conservation Foundation (formed in 1975).[4][19]

In November and December 1976, 7,000 people marched through the streets of Australian cities, protesting against uranium mining. The Uranium Moratorium group was formed and it called for a five-year moritorium on uranium mining. In April 1977 the first national demonstration co-ordinated by the Uranium Moratorium brought around 15,000 demonstrators into the streets of Melbourne, 5,000 in Sydney, and smaller numbers elsewhere.[20] A National signature campaign attracted over 250,000 signatures calling for a five-year moratorium. In August, another demonstration brought 50,000 people out nationally and the opposition to uranium mining looked like a potential political force.[20][21]

In 1977, the Australian Labor Party (ALP) national conference passed a motion in favour of an indefinite moratorium on uranium mining, and the anti-nuclear movement acted to support the Labor Party and help it regain office. However, a setback for the movement occurred in 1982 when another ALP conference overturned its anti-uranium policy in favour of a "one mine policy". After the ALP won power in 1983, the 1984 ALP conference voted in favour of a "Three mine policy".[22] This referred to the then three existing uranium mines in Australia, Nabarlek, Ranger and Roxby Downs/Olympic Dam, and articulated ALP support for pre-existing mines and contracts, but opposition to any new mining.[23]

1980s and 1990s

Between 1979 and 1984, the majority of what is now Kakadu National Park was created, surrounding but not including the Ranger uranium mine. Tension between mining and conservation values led to long running controversy around mining in the Park region.

The two themes for the 1980 Hiroshima Day march and rally in Sydney, sponsored by the Movement Against Uranium Mining (MAUM), were: "Keep uranium in the ground" and "No to nuclear war." Later that year, the Sydney city council officially proclaimed Sydney nuclear-free, in an action similar to that taken by many other local councils throughout Australia.[24]

In the 1980s, academic critics (such as Jim Falk) discussed the "deadly connection" between uranium mining, nuclear reactors and nuclear weapons, linking Australia's nuclear policy to nuclear proliferation and the "plutonium economy".[6]

In the 1980s, Australia experienced a significant growth of nuclear disarmament activism:

On Palm Sunday 1982, an estimated 100,000 Australians participated in anti-nuclear rallies in the nation's biggest cities. Growing year by year, the rallies drew 350,000 participants in 1985.[24] The movement focused on halting Australia's uranium mining and exports, abolishing nuclear weapons, removing foreign military bases from Australia's soil, and creating a nuclear-free Pacific. Public opinion surveys found that about half of Australians opposed uranium mining and export, as well as the visits of U.S. nuclear warships, that 72 percent thought the use of nuclear weapons could never be justified, and that 80 percent favoured building a nuclear-free world.[24]

The Nuclear Disarmament Party won a Senate seat in 1984, but soon faded from the political scene.[25] The years of the Hawke-Keating ALP governments (1983–1996) were characterised by an "uneasy standoff in the uranium debate". The ALP acknowledged community feeling against uranium mining but was reluctant to move against the industry.[26][27]

The 1986 Palm Sunday anti-nuclear rallies drew 250,000 people. In Melbourne, the seamen's union boycotted the arrival of foreign nuclear warships.[24]

Australia's only nuclear energy education facility, the former School of Nuclear Engineering at the University of New South Wales, closed in 1986.[28]

By the late 1980s, the price of uranium had fallen, and the costs of nuclear power had risen, and the anti-nuclear movement seemed to have won its case. The Campaign Against Nuclear Energy disbanded itself in 1988,[6] two years after the Chernobyl Disaster.

The government policy preventing new uranium mines continued into the 1990s, despite occasional reviews and debate. Following protest marches in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane during 1998, a proposed mine at Jabiluka was blocked.[26][27]

Also in 1998, there was a proposal from an international consortium, Pangea Resources, to establish a nuclear waste dump in Western Australia. The plan, to store 20 per cent of the world's spent nuclear fuel and weapons material, was "publicly condemned and abandoned".[25][29]

2000s

In 2000, the Ranger Uranium Mine in the Northern Territory and the Roxby Downs/Olympic Dam mine in South Australia continued to operate, but Narbarlek Uranium Mine had closed. A third uranium mine, Beverley Uranium Mine in SA, was also operating. Several advanced projects, such as Honeymoon in SA, Jabiluka in the Northern Territory and Yeelirrie in WA were on hold because of political and indigenous opposition.[25][27]

In May 2000 there was an anti-nuclear demonstration at the Beverley Uranium Mine, which involved about 100 protesters. Ten of the protesters were mistreated by police and were later awarded more than $700,000 in damages from the South Australian government.[30]

Following the McClelland Royal Commission, a large clean-up was completed in outback South Australia in 2000, after nuclear testing at Maralinga during the 1950s contaminated the region. The cleanup lasted three years, and cost over A$100 million, but there was controversy over the methods used and success of the operation.[25]

As uranium prices began rising from about 2003, proponents of nuclear power advocated it as a solution to global warming and the Australian government began taking an interest. However, in June 2005, the Senate passed a motion opposing nuclear power for Australia.[25] Then, in November 2006, the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Industry and Resources released a pro-nuclear report into Australia's uranium.[31] In late 2006 and early 2007, then Prime Minister John Howard made widely reported statements in favour of nuclear power, on environmental grounds.[26]

Faced with these proposals to examine nuclear power as a possible response to climate change, anti-nuclear campaigners and scientists in Australia emphasised claims that nuclear power could not significantly substitute for other power sources, and that uranium mining itself could become a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions.[7][8] Anti-nuclear campaigns were given added impetus by public concern about the sites for possible reactors: fears exploited by anti-nuclear power political parties in the lead-up to a national election in 2007.[32][33]

The Rudd Labor government was elected in November 2007 and is opposed to nuclear power for Australia.[2][9] The anti-nuclear movement continues to be active in Australia, opposing expansion of existing uranium mines,[34] lobbying against the development of nuclear power in Australia, and criticising proposals for nuclear waste disposal sites, the main candidate being Muckaty station in the Northern Territory.[35]

As of October 2009, the Australian government was continuing to plan for a nuclear waste dump in the Northern Territory. However, there has been opposition from indigenous people, the NT government, and wider NT community.[36] In November 2009, about 100 anti-nuclear protesters assembled outside the Alice Springs parliamentary sittings, urging the Northern Territory Government not to approve a nearby uranium mine site.[37]

2010s

As of early April 2010, more than 200 environmentalists and indigenous people gathered in Tennant Creek to oppose a radioactive waste dump being built on Muckaty Station in the Northern Territory.[38]

Western Australia has a significant share of the Australia's uranium reserves, but between 2002 and 2008, a state-wide ban on uranium mining was in force. The ban was lifted when the Liberal Party was voted into power in the state and, as of 2010, many companies are exploring for uranium in Western Australia. One of the industry's major players, the mining company BHP Billiton, plans to develop the Yeelirrie uranium project in 2011 in a 17 billion dollar project.[39] Two other projects in Western Australia are further advanced then BHP's Yeelirrie, these being the Lake Way uranium project, which is pursued by Toro Energy and scheduled for production by 2013, and the Lake Maitland uranium project, pursued by Mega Uranium, which has a proposed start-of-production date of 2012.[40][41][42]

As of late 2010, there are calls for Australians to debate whether the nation should adopt nuclear power as part of its energy mix. Nuclear power is seen to be "a divisive issue that can arouse deep passions among those for and against".[28]

Following the March 2011 Fukushima nuclear emergency in Japan, where three nuclear reactors were damaged by explosions, Ian Lowe sees the nuclear power option as being risky and unworkable for Australia. Lowe says nuclear power is too expensive, with insurmountable problems associated with waste disposal and weapons proliferation. It is also not a fast enough response to address climate change. Lowe advocates renewable energy which is "quicker, less expensive and less dangerous than nuclear".[43]

In December 2011, the sale of uranium to India was a contentious issue. MPs clashed over the issue and protesters were marched from Sydney's convention centre before Prime Minister Julia Gillard's motion to remove a party ban on uranium sales to India was narrowly supported 206 votes to 185. Long-time anti-nuclear campaigner Peter Garrett MP spoke against the motion.[44]

In March 2012, hundreds of anti-nuclear demonstrators converged on the Australian headquarters of global mining giants BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto. The 500-strong march through southern Melbourne called for an end to uranium mining in Australia, and included speeches and performances by representatives of the expatriate Japanese community as well as Australia's Indigenous communities, who are concerned about the effects of uranium mining near tribal lands. There were also events in Sydney.[45]

A site within Muckaty Station is being considered for Australia's low-level and intermediate-level radioactive waste storage and disposal facility. However, the plan is subject to a Federal Court challenge due to be heard early in 2013.

Ban on nuclear reactors

Nuclear reactors are banned in Queensland[46] and Tasmania.[47]

Currently, uranium mining is prohibited in New South Wales under the Uranium Prohibition Act of 1986.[48]

Issues

The case against nuclear power and uranium mining in Australia has been concerned with the environmental, political, economic, social and cultural impacts of nuclear energy; with the shortcomings of nuclear power as an energy source; and with presenting a sustainable energy strategy. The most prominent adverse impact of nuclear power is seen to be its potential contribution towards proliferation of nuclear weapons. For example, the 1976 Ranger Inquiry report stated that "The nuclear power industry is unintentionally contributing to an increased risk of nuclear war. This is the most serious hazard associated with the industry".[17]

The health risks associated with nuclear materials have also featured prominently in Australian anti-nuclear campaigns. This has been the case worldwide because of incidents like the Chernobyl disaster, but Australian concerns have also involved specific local factors such as controversy over the health effects of nuclear testing in Australia and the South Pacific, and the emergence of prominent anti-nuclear campaigner Helen Caldicott, who is a medical practitioner.

The economics of nuclear power has been a factor in anti-nuclear campaigns, with critics arguing that such power is uneconomical in Australia,[49] particularly given the country's abundance of coal resources.

According to the anti-nuclear movement, most of the problems with nuclear power today are much the same as in the 1970s. Nuclear reactor accidents still occur and there is no convincing solution to the problem of long-lived radioactive waste. Nuclear weapons proliferation continues to occur, notably in Pakistan and North Korea, building on facilities and expertise from civilian nuclear operations. The alternatives to nuclear power, efficient energy use and renewable energy (especially wind power), have been further developed and commercialised.[26]

Public opinion

A 2009 poll conducted by the Uranium Information Centre found that Australians in the 40 to 55 years age group are the "most trenchantly opposed to nuclear power".[50] This generation was raised during the Cold War, experienced the anti-nuclear movement of the 1970s, witnessed the 1979 partial meltdown of the Three Mile Island reactor in the USA, and the 1986 Chernobyl disaster. It was the generation which was also subject to cultural influences including feature films such as the "nuclear industry conspiracies" The China Syndrome and Silkwood and the apocalyptic Dr Strangelove. Younger people are "less resistant" to the idea of nuclear power for Australia.[50]

Indigenous land owners have consistently opposed uranium mining and have spoken out about the adverse impact it has on their communities.[11]

Active groups

|

|

Individuals

There are several prominent Australians who have publicly expressed anti-nuclear views:

|

See also

- Anti-nuclear protests

- Australian Uranium Association

- Clean Energy Future Group

- History of the anti-nuclear movement

- International Commission on Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament

- List of anti-nuclear groups

- List of Australian inquiries into uranium mining

- Lists of nuclear disasters and radioactive incidents

- Renewable energy commercialization

- Renewable energy in Australia

- Say Yes demonstrations

References

- ^ Green, Jim (26 August 1998). Australia's anti-nuclear movement: a short history Green Left Online. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ a b Koutsoukis, Jason (25 November 2007). Rudd romps to historic win The Age. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ a b c McLeod, Roy (1995). "Resistance to Nuclear Technology: Optimists, Opportunists and Opposition in Australian Nuclear History" in Martin Bauer (ed) Resistance to New Technology, Cambridge University Press, pp. 171–173.

- ^ a b Hutton, Drew and Connors, Libby (1999). A History of the Australian Environmental Movement, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Friends of the Earth (Canberra) (January 1984). Strategy against nuclear power

- ^ a b c McLeod, Roy (1995). "Resistance to Nuclear Technology: Optimists, Opportunists and Opposition in Australian Nuclear History" in Martin Bauer (ed) Resistance to New Technology, Cambridge University Press, pp. 175–177.

- ^ a b Diesendorf, Mark (2007). Paths to a Low-Carbon Future: Reducing Australia’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions by 30 per cent by 2020 (PDF)

- ^ a b Green, Jim (2005). Nuclear Power: No Solution to Climate Change (PDF)

- ^ a b Lewis, Steve and Kerr, Joseph (30 December 2006). Support for N-power falls The Australian.

- ^ Work begins on Honeymoon uranium mine (24 April 2009), ABC News. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ a b Vaisutis, Justine (April 2010). Indigenous communities getting dumped in it. Again. Habitat Australia, Vol. 38, No. 2, p. 22.

- ^ a b Australian Government. A toxic legacy: British nuclear weapons testing in Australia Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Women with Ban the Bomb banner during Peace march on Sunday 5 April 1964, Brisbane, Australia Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Girl with placard Ban nuclear tests during Peace march on Sunday 5 April 1964, Brisbane, Australia Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Falk, Jim (1982). Gobal Fission:The Battle Over Nuclear Power, p. 260.

- ^ 'Gorton gave nod to nuclear power plant', (1 January 2000), The Age.

- ^ a b c d e Martin, Brian (Summer 1982). The Australian anti-uranium movement Alternatives: Perspectives on Society and Environment, Volume 10, Number 4, pp. 26–35. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Dewes, Kate and Green, Robert (1999). Aotera/ New Zealand at the World Court The Raven Press, pp. 11–15.

- ^ a b Bauer, Martin (ed) (1995). Resistance to New Technology, Cambridge University Press, p. 173.

- ^ a b Falk, Jim (1982). Gobal Fission:The Battle Over Nuclear Power, pp. 264–5.

- ^ Cawte, Alice (1992). Atomic Australia 1944–1990, New South Wales University Press, p. 156.

- ^ Burgmann, Verity (2003). Power, Profit and Protest pp. 174–175. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Evans, Chris (23 March 2007). Labor & uranium: an evolution, Labor E-herald.

- ^ a b c d Wittner, Lawrence S. (22 June 2009). Nuclear Disarmament Activism in Asia and the Pacific, 1971–1996 The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 25-5-09.

- ^ a b c d e Four Corners. (2005). Chronology – Australia's Nuclear Political History Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d Martin, Brian (Second Quarter 2007). Opposing nuclear power: past and present Social Alternatives, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 43–47. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ a b c Anti-uranium demos in Australia (5 April 1998), BBC News. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ a b Agelidis, Vassilios (7 December 2010). Too late for nuclear ABC News.

- ^ Holland, Ian (2002). 'Waste Not Want Not? Australia and the Politics of High-level Nuclear Waste', Australian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 37, No. 2, pp. 283–301.

- ^ Anti-nuke protesters awarded $700,000 for 'feral' treatment (9 April 2010), Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ House of Representatives Standing Committee on Industry and Resources (2006). Australia’s uranium – Greenhouse friendly fuel for an energy hungry world Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Franklin, Matthew and Wardill, Steven (6 June 2006). PM nukes Labor's "campaign of fear", Courier-Mail.

- ^ Kerr, Joseph and Lewis, Steve (30 December 2006). Support for N-power plants falls, The Australian.

- ^ Pedersen, Ty (26 January 2008). Olympic Dam expansion: a risk too great, Green Left Weekly. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Anti-nuclear campaigners say Muckaty will be dumped, (26 November 2007). ABC News.

- ^ Sweeney, Dave (October 2009). Australia's Nuclear Landscape, Habitat Australia, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Nancarrow, Kirsty (24 November 2009). 100 protest in Alice against uranium mine, ABC News.

- ^ Hundreds rally to stop nuclear dump (5 April 2010), ABC News.

- ^ Boylan, Jessie (9 August 2010). Australia's aboriginal communities clamour against uranium mining The Guardian.

- ^ Great science debates of the next decade: Spotlight on uranium perthnow.com.au, published: 1 February 2010, accessed: 13 February 2011

- ^ Toro gets approval for uranium project The Sydney Morning Herald, published: 7 January 2010, accessed: 13 February 2011

- ^ Michael Lampard. "Uranium Outlook to 2013–14". Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ Ian Lowe (20 March 2011). "No nukes now, or ever". The Age.

- ^ Matthew Johnston (4 December 2011). "Labor supports Julia Gillard's plan to sell uranium to India". Herald Sun.

- ^ Phil Mercer (11 March 2012). "Australian Rallies Remember Fukushima Disaster". VOA News.

- ^ "Queensland bans nuclear facilities". Allens Arthur Robinson. 1 March 2007.

- ^ Minter Ellison (10 December 2006). "Australias States React Strongly to Switkowski Report". World Services Group.

- ^ New South Wales Government (1986). "Uranium Mining and Nuclear Facilities" (PDF).

- ^ See, for example, Brian Martin (1982). Nuclear Power and the Western Australia Electricity Grid, Search, Vol. 13, No. 5-6.

- ^ a b c Strong, Geoff and Munro, Ian (13 October 2009). Going Fission The Age.

- ^ Anti-Nuclear Alliance of Western Australia. Anti-Nuclear Alliance of Western Australia Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ Australian Conservation Foundation. Nuclear Free Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ Greens Nuclear Policy

- ^ a b Peter Watts (31 January 2012). "Uranium should stay in the ground". Green Left.

- ^ Australian Nuclear Free Alliance Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ Australian Conservation Foundation. Australian Nuclear Free Alliance Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ New alliance to mount anti-nuclear election fight ABC News, 13 August 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ Cycle Against the Nuclear Cycle. Cycle Against the Nuclear Cycle Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ EnergyScience. The Energy debate Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ Australian Nuclear Issues Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ Greenpeace Australia Pacific. Nuclear power Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ Friends of the Earth International (2004). Aboriginal women win battle against Australian Government Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ The Australia Institute. Nuclear Plants – Where would they go? Media release, 30 January 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ The Sustainable Energy and Anti-Uranium Service Inc. The Sustainable Energy and Anti-Uranium Service Inc. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ The Wilderness Society. The Nation said YES! to a Nuclear Free Australia Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ The Wilderness Society launches new anti-nuclear TV Ad Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ Women Against Nuclear Energy

- ^ J.A. Camilleri. The Myth of the Peaceful Atom Journal of International Studies, Vol. 6, No. 2, Autumn 1977, pp. 111–127.

- ^ Courtney Trenwith (22 June 2011). "Get with the times: Parliament told nuclear power is 'so last century'". WAtoday.

- ^ "Uranium forum addresses Japan crisis fallout". ABC News. 7 June 2011.

- ^ Bill Williams. Nuclear delusions keep mushrooming The Age, 15 October 2009.

- ^ James Norman and Bill Williams. Stars align in quest to rid the world of nukes The Age, 24 September 2009.

Bibliography

- Cooke, Stephanie (2009). In Mortal Hands: A Cautionary History of the Nuclear Age, Black Inc.

- Diesendorf, Mark (2009). Climate Action: A Campaign Manual for Greenhouse Solutions, University of New South Wales Press.

- Diesendorf, Mark (2007). Greenhouse Solutions with Sustainable Energy, University of New South Wales Press.

- Elliott, David (2007). Nuclear or Not? Does Nuclear Power Have a Place in a Sustainable Energy Future?, Palgrave.

- Falk, Jim (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press.

- Giugni, Marco (2004). Social Protest and Policy Change: Ecology, Antinuclear, and Peace Movements in Comparative Perspective, Rowman and Littlefield.

- Lovins, Amory B. (1977). Soft Energy Paths: Towards a Durable Peace, Friends of the Earth International, ISBN 0-06-090653-7

- Lovins, Amory B. and Price, John H. (1975). Non-Nuclear Futures: The Case for an Ethical Energy Strategy, Ballinger Publishing Company, 1975, ISBN 0-88410-602-0

- Lowe, Ian (2007). Reaction Time: Climate Change and the Nuclear Option, Quarterly Essay.

- Parkinson, Alan (2007). Maralinga: Australia’s Nuclear Waste Cover-up, ABC Books.

- Pernick, Ron and Wilder, Clint (2007). The Clean Tech Revolution: The Next Big Growth and Investment Opportunity, Collins, ISBN 978-0-06-089623-2

- Schneider, Mycle, Steve Thomas, Antony Froggatt, Doug Koplow (August 2009). The World Nuclear Industry Status Report, German Federal Ministry of Environment, Nature Conservation and Reactor Safety.

- Smith, Jennifer (Editor), (2002). The Antinuclear Movement, Cengage Gale.

- Walker, J. Samuel (2004). Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective, University of California Press.

External links

- Contemporary critiques of nuclear power by Australian scientists

- Australian Map Of Nuclear Sites

- Nuclear Knights, a book by anti-nuclear campaigner Brian Martin.

- Strategy against nuclear power, an anti-nuclear campaign strategy produced by Friends of the Earth.

- Backs to the Blast, an Australian Nuclear Story, a documentary about nuclear testing in Australia.

- Stop Uranium Mining! Australia's Decade of Protest 1975–1985, a history of anti-nuclear protest in the 1970s and 1980s.