British Empire: Difference between revisions

Grenavitar (talk | contribs) m →Colonisation: years -> years' |

add bibliog |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

The British Empire was at one time referred to as "[[the empire on which the sun never sets]]", as due to its vastness, the sun was always shining on one of its [[colonies]]. |

The British Empire was at one time referred to as "[[the empire on which the sun never sets]]", as due to its vastness, the sun was always shining on one of its [[colonies]]. |

||

The term "British Empire" was used by historians as early as 1708: (John Oldmixon, ''The British Empire in America, Containing the History of the Discovery, Settlement, |

|||

Progress and Present State of All the British Colonies, on the Continent and Islands of America'' (London, 1708)) before that the term was "English Empire," as in Nathaniel Crouch, ''The English Empire in America: Or a Prospect of His Majesties Dominions in the West-Indies (London, 1685).'' [Armitage pp 174-5] |

|||

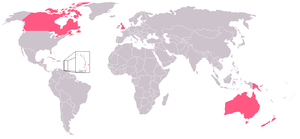

[[Image:British Empire 1897.jpg|thumb|350px|right|The British Empire in 1897, marked in pink, the traditional colour for Imperial British dominions on maps.]] |

[[Image:British Empire 1897.jpg|thumb|350px|right|The British Empire in 1897, marked in pink, the traditional colour for Imperial British dominions on maps.]] |

||

| Line 209: | Line 213: | ||

Although the white-dominated [[Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland]] ended in the independence of [[Malawi]] (formerly [[Nyasaland]]) and [[Zambia]] (the former Northern Rhodesia) in 1964, Southern Rhodesia's white minority (a [[self-governing colony]] since 1923) declared independence with their [[Unilateral Declaration of Independence (Rhodesia)|UDI]] rather than submit to equality with [[black African]]s. The support of South Africa's apartheid government kept the Rhodesian regime in place until 1979, when agreement was reached on majority rule in an independent [[Zimbabwe]]. |

Although the white-dominated [[Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland]] ended in the independence of [[Malawi]] (formerly [[Nyasaland]]) and [[Zambia]] (the former Northern Rhodesia) in 1964, Southern Rhodesia's white minority (a [[self-governing colony]] since 1923) declared independence with their [[Unilateral Declaration of Independence (Rhodesia)|UDI]] rather than submit to equality with [[black African]]s. The support of South Africa's apartheid government kept the Rhodesian regime in place until 1979, when agreement was reached on majority rule in an independent [[Zimbabwe]]. |

||

Most of Britain's Caribbean territories opted for eventual separate independence after the failure of the [[West Indies Federation]] (1958–62): [[Jamaica]] and [[Trinidad and Tobago]] (1962) were followed into statehood by [[Barbados]] (1966) and the smaller islands of the eastern Caribbean (1970s and 1980s). Britain's Pacific dependencies underwent a similar process of decolonisation in the latter decades. At the end of Britain's 99-year lease of the mainland [[New Territories]], [[Hong Kong]] became a [[Special Administrative Region]] of the [[People's Republic of China]] in 1997. |

Most of Britain's Caribbean territories opted for eventual separate independence after the failure of the [[West Indies Federation]] (1958–62): [[Jamaica]] and [[Trinidad and Tobago]] (1962) were followed into statehood by [[Barbados]] (1966) and the smaller islands of the eastern Caribbean (1970s and 1980s). Britain's Pacific dependencies underwent a similar process of decolonisation in the latter decades. At the end of Britain's 99-year lease of the mainland [[New Territories]], [[Hong Kong]] became a [[Special Administrative Region]] of the |

||

[[People's Republic of China]] in 1997. |

|||

==References== |

|||

===Overviews=== |

|||

* Bryant, Arthur, ''The History of Britain and the British Peoples'', 3 vols. (London, 1984–90). |

|||

* Judd, Denis, ''Empire: The British Imperial Experience, From 1765 to the Present'' (London, 1996). |

|||

* T. O. Lloyd; ''The British Empire, 1558-1995'' Oxford University Press, 1996 |

|||

* Louis, William. Roger (general editor), ''The Oxford History of the British Empire'', 5 vols. (Oxford, 1998–99). |

|||

* Marshall, P. J. (ed.), ''The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire'' (Cambridge, 1996). |

|||

* James S. Olson and Robert S. Shadle; ''Historical Dictionary of the British Empire'' 1996 |

|||

* Rose, J. Holland, A. P. Newton and E. A. Benians (gen. eds.), ''The Cambridge History of the British Empire'', 9 vols. (Cambridge, 1929–61). |

|||

* Simon C. Smith. ''British Imperialism 1750-1970'' Cambridge University Press, 1998. brief |

|||

===Specialized scholarly studies=== |

|||

* Adams, James Truslow, 'On the Term “British Empire”', American Historical Review, 27 (1922), 485–9. |

|||

* Andrews, Kenneth R., Trade, Plunder and Settlement: Maritime Enterprise and the Genesis of the British Empire, 1480–1630 (Cambridge, 1984). |

|||

* David Armitage; ''The Ideological Origins of the British Empire'' Cambridge University Press, 2000. |

|||

* Armitage, David, 'Greater Britain: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis?' American Historical Review, 104 (1999), 427–45. |

|||

* Armitage, David (ed.), Theories of Empire, 1450–1800 (Aldershot, 1998). |

|||

* Charles A. Barone, Marxist Thought on Imperialism: Survey |

|||

and Critique (London: Macmillan, 1985) |

|||

* Bernard Bailyn and Philip D. Morgan (eds.), Strangers within the Realm: Cultural Margins of the First British Empire (Chapel Hill, 1991) |

|||

* Barker, Sir Ernest, The Ideas and Ideals of the British Empire (Cambridge, 1941). |

|||

* W. Baumgart, ''Imperialism: The Idea and Reality of British and French Colonial Expansion, 1880-1914'' (Oxford University |

|||

Press, 1982) |

|||

* Beer, G. L., The Origins of the British Colonial System 1578–1660 (London, 1908). |

|||

* Bennett, George (ed. ), The Concept of Empire: Burke to Attlee, 1774–1947 (London, 1953). |

|||

* J. M. Blaut, The Colonizers' Model of the World, London 1993 |

|||

* Philip Darby, The Three Faces of Imperialism:British and American Approaches to Asia and Africa, 1870-1970 (Yale University Press, 1987 |

|||

* Harlow, V. T., The Founding of the Second British Empire, 1763–1793, 2 vols. (London, 1952–64). |

|||

* Edward Ingrain. ''The British Empire as a World Power'' (2001) |

|||

* Robert Johnson. ''British Imperialism'' Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. historiography |

|||

* Kennedy, Paul, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery (London, 1976). |

|||

* Knorr, Klaus E., British Colonial Theories 1570–1850 (Toronto, 1944). |

|||

* Mehta, Uday Singh, Liberalism and Empire: A Study in Nineteenth-Century British Liberal Thought (Chicago, 1999). |

|||

* Pocock, J. G. A., 'The Limits and Divisions of British History: In Search of the Unknown Subject', American Historical Review, 87 (1982), 311–36. |

|||

==Extent== |

==Extent== |

||

[[Image:BritishEmpire1919.PNG|thumb|300px|The British Empire at its zenith in 1919.]] |

[[Image:BritishEmpire1919.PNG|thumb|300px|The British Empire at its zenith in 1919.]] |

||

Revision as of 04:53, 2 April 2006

The British Empire was, at one time, the foremost global power, and the most extensive empire in the history of the world. It was a product of the European Age of Discovery that began with the global maritime explorations of Portugal and Spain in the late 15th century.

By 1921 the British Empire held sway over a population of about 470–570 million people; approximately a quarter of the world's population. It covered about 14.3 million square miles (more than 37 million km²), about a quarter of the world's total land area. Though it has since almost completely evolved into the Commonwealth of Nations, there remains a strong influence across the world, such as in economic practice, legal and government systems, the spread of many traditionally British sports (such as cricket and football) and also the spread of the English language itself.

The British Empire was at one time referred to as "the empire on which the sun never sets", as due to its vastness, the sun was always shining on one of its colonies.

The term "British Empire" was used by historians as early as 1708: (John Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, Containing the History of the Discovery, Settlement, Progress and Present State of All the British Colonies, on the Continent and Islands of America (London, 1708)) before that the term was "English Empire," as in Nathaniel Crouch, The English Empire in America: Or a Prospect of His Majesties Dominions in the West-Indies (London, 1685). [Armitage pp 174-5]

Background: The English and Scottish Empires

The Anglo-Norman Kingdom

In 1066, William, Duke of Normandy, conquered England and asserted his right to be king, giving England its first overseas territory, Normandy (This can also be seen as giving Normandy it's first overseas territory) . The new rulers had dual roles. First, as kings of England they were sovereign lords. Second, as dukes of Normandy, they were vassals of the kings of France. This led to centuries of conflicts which ended with their loss of French holdings in 1558. In the meantime, the annexation of Ireland began in 1172 and Wales was conquered in 1282.

Growth of the overseas empire

The overseas British Empire (in the sense of British oceanic exploration and settlement outside of Europe and the British Isles) was rooted in the pioneering maritime policies of King Henry VII, who reigned from 1485 to 1509. Building on commercial links in the wool trade promoted during the reign of his predecessor King Richard III, Henry established the modern English merchant marine system, which greatly expanded English shipbuilding and seafaring. The merchant marine also supplied the basis for the mercantile institutions that would play such a crucial role in later British imperial ventures, such as the Massachusetts Bay Company and the British East India Company. Henry's financial reforms made the English Exchequer solvent, which helped to underwrite the development of the Merchant Marine. Henry also ordered construction of the first English dry dock, at Portsmouth, and made improvements to England's small navy. Additionally, Henry sponsored the voyages of the Italian mariner John Cabot in 1496 and 1497 that established England's first overseas colony - a fishing settlement - in Newfoundland, which Cabot claimed on behalf of Henry.

Henry VIII and the rise of the Royal Navy

The foundations of sea power, having been laid during Henry VII's reign, were gradually expanded to protect English trade and open up new routes. King Henry VIII founded the modern English navy (though the plans to do so were put into motion during his father's reign), more than tripling the number of warships and constructing the first large vessels with heavy, long-range guns. He initiated the Navy's formal, centralised administrative apparatus, built new docks, and constructed the network of beacons and lighthouses that greatly facilitated coastal navigation for English and foreign merchant sailors. Henry thus established the munitions-based Royal Navy that was able to hold off the Spanish Armada in 1588, and his innovations provided the seed for the imperial navy of later day.

The Elizabethan era

During the reign of the Tudor Queen Elizabeth I, Sir Francis Drake circumnavigated the globe in the years 1577 to 1580, fleeing from the Spanish, only the second to accomplish this feat after Ferdinand Magellan's expedition.

In 1579, Drake landed somewhere in northern California and claimed for the English Crown what he named Nova Albion ("New Albion", Albion being an ancient name for England), though the claim was not followed by settlement. Subsequent maps spell out Nova Albion to the north of all New Spain. Thereafter, England's interests outside Europe grew steadily, promoted by John Dee, who coined the phrase "British Empire". An expert in navigation, he was visited by many of the early English explorers before and after their expeditions. He was a Welshman, and his use of the term "British" fitted with the Welsh origins of Elizabeth's Tudor family, although his conception of empire was derived from Dante's book Monarchia.

Humphrey Gilbert followed on Cabot's original claim when he sailed to Newfoundland in 1583 and declared it an English colony on August 5 at St John's. Sir Walter Raleigh organised the first colony in Virginia in 1587 at Roanoke Island. Both Gilbert's Newfoundland settlement and the Roanoke colony were short-lived, however, and had to be abandoned due to food shortages, severe weather, shipwrecks, and hostile encounters with indigenous tribes on the American continent.

The Elizabethan era built on the past century's imperial foundations by expanding Henry VIII's navy, promoting Atlantic exploration by English sailors, and further encouraging maritime trade especially with the Netherlands and the Hanseatic League. The nearly twenty year Anglo-Spanish War (1585 - 1604), which started well for England with the sack of Cadiz and the repulse of the Spanish Armada, soon turned Spain's way with a number of serious defeats which sent the Royal Navy into decline and allowed Spain to retain effective control of the Atlantic sea lanes, thwarting English hopes of establishing colonies in North America. However it did give English sailors and shipbuilders vital experience.

The Stuart era

In 1604, King James I of England negotiated the Treaty of London, ending hostilities with Spain, and the first permanent English settlement followed in 1607 at Jamestown, Virginia. During the next three centuries, England extended its influence overseas and consolidated its political development at home. In 1707, under the Acts of Union, the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland were united in Westminster, London, as the Parliament of Great Britain.

Scottish Empire

There were several pre-union attempts at creating a Scottish Overseas Empire, with various Scottish settlements in North and South America. The most famous of these was the disastrous Darién scheme which attempted to establish a settlement colony and trading post in Panama to foster trade between Scotland and the Far East.

After union many Scots, especially in Canada, Jamaica, India, Australia and New Zealand, took up posts as administrators, doctors, lawyers and teachers. Progressions in Scotland itself during the Scottish enlightenment led to advancements throughout the empire. Scots settled across the Empire as it developed and built up their own communities such as Dunedin in New Zealand.

Colonisation

In 1583 Sir Humphrey Gilbert claimed the island of Newfoundland as England's for Elizabeth I, reinforcing John Cabot's prior claim to the island in 1497, for Henry VII, as England's first overseas colony. Gilbert's shipwreck prevented ensuing settlement in Newfoundland, other than the seasonal cod fishermen who had frequented the island since 1497. However, the Jamestown colonists, led by Captain John Smith, overcame the severe privations of the winter in 1607 to found England's first permanent overseas settlement. The empire thus took shape during the early 17th century, with the English settlement of the eastern colonies of North America, which would later become the original United States as well as Canada's Atlantic provinces, and the colonisation of the smaller islands of the Caribbean such as Jamaica and Barbados.

The sugar-producing colonies of the Caribbean, where slavery became the basis of the economy, were at first England's most important and lucrative colonies. The American colonies providing tobacco, cotton, and rice in the south and naval materiel and furs in the north were less financially successful, but had large areas of good agricultural land and attracted far larger numbers of English emigrants.

England's American empire was slowly expanded by war and colonisation, England gaining control of New Amsterdam (later New York) via negotiations following the Second Anglo-Dutch War. The growing American colonies pressed ever westward in search of new agricultural lands.

During the Seven Years' War the British defeated the French at the Plains of Abraham and captured all of New France in 1760, giving Britain control over the greater part of North America.

Later, settlement of Australia (starting with penal colonies from 1788) and New Zealand (under the crown from 1840) created a major zone of British migration. The entire Australian continent was claimed for Britain when Matthew Flinders proved New Holland and New South Wales to be a single land mass by completing a circumnavigation of it in 1803. The colonies later became self-governing colonies and became profitable exporters of wool and gold.

See also British colonisation of the Americas, Colonial history of America

Free trade and "informal empire"

Main article: Pax Britannica

The old British colonial system began to decline in the 18th century. During the long period of unbroken Whig dominance of domestic political life (1714–62), the Empire became less important and less well-regarded, until an ill-fated attempt (largely involving taxes, monopolies, and zoning) to reverse the resulting "salutary neglect" (or "benign neglect") provoked the American War of Independence (1775–83), depriving Britain of her most populous colonies.

The period is sometimes referred to as the end of the "first British Empire", indicating the shift of British expansion from the Americas in the 17th and 18th centuries to the "second British Empire" in Asia and later also Africa from the 18th century. The loss of the Thirteen Colonies showed that colonies were not necessarily particularly beneficial in economic terms, since Britain could still profit from trade with the ex-colonies without having to pay for their defence and administration.

Mercantilism, the economic doctrine of competition between nations for a finite amount of wealth which had characterised the first period of colonial expansion, now gave way in Britain and elsewhere to the laissez-faire economic liberalism of Adam Smith and successors like Richard Cobden.

The lesson of Britain's North American loss — that trade might be profitable in the absence of colonial rule — contributed to the extension in the 1840s and 1850s of self-governing colony status to white settler colonies in Canada and Australasia whose British or European inhabitants were seen as outposts of the "mother country". Ireland was treated differently because of its geographic proximity, and incorporated into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801; due largely to the impact of the Irish Rebellion of 1798 against British rule.

During this period, Britain also outlawed the slave trade (1807) and soon began enforcing this principle on other nations. By the mid-19th century Britain had largely eradicated the world slave trade. Slavery itself was abolished in the British colonies in 1834, though the phenomenon of indentured labour retained much of its oppressive character until 1920.

The end of the old colonial and slave systems was accompanied by the adoption of free trade, culminating in the repeal of the Corn Laws and Navigation Acts in the 1840s. Free trade opened the British market to unfettered competition, stimulating reciprocal action by other countries during the middle quarters of the 19th century.

Some argue that the rise of free trade merely reflected Britain's economic position and was unconnected with any true philosophical conviction. Despite the earlier loss of 13 of Britain's North American colonies, the final defeat in Europe of Napoleonic France in 1815 left Britain the most successful international power. While the Industrial Revolution at home gave her an unrivalled economic leadership, the Royal Navy dominated the seas. The distraction of rival powers by European matters enabled Britain to pursue a phase of expansion of her economic and political influence through "informal empire" underpinned by free trade and strategic pre-eminence.

Between the Congress of Vienna of 1815 and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, Britain was the world's sole industrialised power, with over 30% of the global industrial output in 1870. As the "workshop of the world", Britain could produce finished manufactures so efficiently and cheaply that they could undersell comparable locally produced goods in foreign markets. Given stable political conditions in particular overseas markets, Britain could prosper through free trade alone without having to resort to formal rule. The Americas in particular (especially in Argentina and the United States) were seen as being well under the informal British trade empire due to Britain's enforcement of the Monroe Doctrine keeping other European nations from establishing formal rule in the area.

British East India Company

Main article: British East India Company

The British East India Company was probably the most successful chapter in the British Empire's history as it was responsible for the annexation of the Indian subcontinent, which would become the British Empire's largest source of revenue, along with the conquest of Hong Kong, Singapore, Ceylon, Malaya (which was also one of the largest sources of revenue) and other surrounding Asian countries, and was thus responsible for establishing Britain's Asian empire, the most important component of the British Empire.

The British East India Company originally began as a joint-stock company of traders and investors based in Leadenhall Street, in the City of London, which was granted a Royal Charter by Elizabeth I in 1600, with the intent to favour trade privileges in India. The Royal Charter effectively gave the newly created Honourable East India Company a monopoly on all trade with the East Indies. The Company transformed from a commercial trading venture to one which virtually ruled India as it acquired auxiliary governmental and military functions, along with a very large private army consisting of local Indian sepoys, who were loyal to their British commanders and were probably the most important factor in Britain's Asian conquest. The British East India Company is regarded by some as the world's first multinational corporation. Its territorial holdings were subsumed by the British crown in 1858, in the aftermath of the events variously referred to as the Sepoy Rebellion or the Indian Mutiny. [1]

The Company also had interests along the routes to India from Great Britain. As early as 1620, the company attempted to lay claim to the Table Mountain region in South Africa, later it occupied and ruled St Helena. The Company also established Hong Kong and Singapore; employed Captain Kidd to combat piracy; and cultivated the production of tea in India. Other notable events in the Company's history were that it held Napoleon captive on Saint Helena, and made the fortune of Elihu Yale. Its products were the basis of the Boston Tea Party in Colonial America.

In 1615, Sir Thomas Roe was instructed by James I to visit the Mughal Emperor Jahangir (who ruled over most of the Indian subcontinent at the time, along with parts of Afghanistan). The purpose of this mission was to arrange for a commercial treaty which would give the Company exclusive rights to reside and build factories in Surat and other areas. In return, the Company offered to provide to the emperor goods and rarities from the European market. This mission was highly successful and Jahangir sent a letter to the King through Sir Thomas. The British East India Company found itself completely dominant over the French, Dutch and Portuguese trading companies in the Indian subcontinent as a result. In 1634, the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan extended his hospitality to the English traders to the region of Bengal, which had the world's largest textile industry at the time. In 1717, the Mughal Emperor at the time completely waived customs duties for the trade, giving the Company a decided commercial advantage in the Indian trade. With the Company's large revenues, it raised its own armed forces from the 1680s, mainly drawn from the indigenous local population, who were Indian sepoys under the command of British officers.

Expansion

The decline of the Mughal Empire, which had separated into many smaller states controlled by local rulers who were often in conflict with one another, allowed the Company to expand its territories, which began in 1757, when the Company came into conflict with the Nawab of Bengal, Siraj Ud Daulah. Under the leadership of Robert Clive, the Company troops and their local allies defeated the Nawab on 23 June 1757 at the Battle of Plassey, mostly due to the treachery of the Nawab's former army chief Mir Jafar. This victory, which resulted in the conquest of Bengal, established the British East India Company as a military as well as a commercial power, and marked the beginning of British rule in India. The wealth gained from the Bengal treasury allowed the Company to significantly strengthen its military might and as a result, extend its territories, conquering most parts of India with the massive Indian army it had acquired.

They fought many wars with local Indian rulers during their conquest of India, the most difficult being the four Anglo-Mysore Wars (between 1766 and 1799) against the South Indian Kingdom of Mysore ruled by Hyder Ali, and later his son Tipu Sultan (The Tiger of Mysore) who developed the use of rockets in warfare. Mysore was only defeated in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War by the combined forces of Britain and of Mysore's neighbours, for which Hyder Ali and especially Tipu Sultan are remembered in India as legendary rulers. After acquiring Mysore's rocket technology, Britain developed many rockets of its own for many wars, in which it later engaged. There were a number of other states which the Company couldn't conquer through military might, mostly in the North, where the Company's presence was ever increasing amidst the internal conflict and dubious offers of protection against one another. Coercive action, threats and diplomacy aided the Company in preventing the local rulers from putting up a united struggle against it. By the 1850s, the Company ruled over most of the Indian subcontinent and as a result, the Company began to function more as a nation and less as a trading concern.

They were also responsible for the illegal opium trade with China against the Qing Emperor's will, which later led to the two Opium Wars (between 1834 and 1860). As a result of the Company's victory in the First Opium War, it established Hong Kong. The Company also had a number of wars with other surrounding Asian countries, the most difficult probably being the three Anglo-Afghan Wars (between 1839 and 1919) against Afghanistan, which were mostly unsuccessful.

Collapse

The Company's rule effectively came to an end exactly a century after its victory at Plassey, when the Indian Mutiny broke out in 1857, known to many Indians as the First War of Independence, which saw many of the Company's Indian sepoys begin an armed uprising against their British commanders, after a period of political unrest triggered by a number of political events. One of the major factors was the Company's introduction of the Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle. The paper cartridges containing the gunpowder were lubricated with animal fat, and had to be bitten open before the powder was poured into the muzzle. Eating cow fat was forbidden for the Hindu soldiers, while pig fat was forbidden for the Muslim soldiers. Although it insisted that neither cow fat nor pig fat was being used, the rumour persisted and many sepoys refused to follow their orders and use the weapons. Another factor was the execution of the Indian sepoy Mangal Pandey who was hanged for attacking and injuring his British superiors, possibly out of insult for the introduction of the Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle or a number of other reasons. These factors combined with a number of other reasons resulted in the Mutiny, which eventually brought about the end of the British East India Company's regime in India, and instead led to 90 years of direct rule of the Indian subcontinent by Britain, after the British East India Company was dissolved. The period of direct British rule in India is known as the British Raj, when the regions now known as India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Myanmar would collectively be known as British India.

Breakdown of Pax Britannica

As the first country to industrialise, Britain had been able to draw on most of the accessible world for raw materials and markets. But this situation gradually deteriorated during the 19th century as other powers began to industrialise and sought to use the state to guarantee their markets and sources of supply. By the 1870s, British manufactures in the staple industries of the Industrial Revolution were beginning to experience real competition abroad.

Industrialisation progressed rapidly in Germany and the United States, allowing them to overtake the "old" British and French economies as world leader in some areas. The German textile and metal industries, for example, had by 1870, surpassed those of Britain in organisation and technical efficiency and usurped British manufactures in the domestic market. By the turn of the century, the German metals and engineering industries would even be producing for the free trade market of the former "workshop of the world".

While invisible exports (banking, insurance and shipping services) kept Britain "out of the red," her share of world trade fell from a quarter in 1880 to a sixth in 1913. Britain was losing out not only in the markets of newly industrialising countries, but also against third-party competition in less-developed countries. Britain was even losing her former overwhelming dominance in trade with India, China, Latin America, or the coasts of Africa.

Britain's commercial difficulties deepened with the onset of the "Long Depression" of 1873–96, a prolonged period of price deflation punctuated by severe business downturns which added to pressure on governments to promote home industry, leading to the widespread abandonment of free trade among Europe's powers (in Germany from 1879 and in France from 1881).

The resulting limitation of both domestic markets and export opportunities led government and business leaders in Europe and later the US to see the solution in sheltered overseas markets united to the home country behind imperial tariff barriers: new overseas subjects would provide export markets free of foreign competition, while supplying cheap raw materials. Although she continued to adhere to free trade until 1932, Britain joined the renewed scramble for formal empire rather than allow areas under her influence to be seized by rivals.

Britain and the New Imperialism

Main article: New Imperialism.

The policy and ideology of European colonial expansion between the 1870s and the outbreak of World War I in 1914 are often characterised as the "New Imperialism". The period is distinguished by an unprecedented pursuit of what has been termed "empire for empire's sake", aggressive competition for overseas territorial acquisitions and the emergence in colonising countries of doctrines of racial superiority which denied the fitness of subjugated peoples for self-government.

During this period, Europe's powers added nearly 8,880,000 sq mi (23,000,000 km²) to their overseas colonial possessions. As it was mostly unoccupied by the Western powers as late as the 1880s, Africa became the primary target of the "new" imperialist expansion, although conquest took place also in other areas — notably south-east Asia and the East Asian seaboard, where the United States and Japan joined the European powers' scramble for territory.

Britain's entry into the new imperial age is often dated to 1875, when the Conservative government of Benjamin Disraeli bought the indebted Egyptian ruler Ismail's shareholding in the Suez Canal to secure control of this strategic waterway, a channel for shipping between Britain and India since its opening six years earlier under Emperor Napoleon III. Joint Anglo-French financial control over Egypt ended in outright British occupation in 1882.

Fear of Russia's centuries-old southward expansion was a further factor in British policy: in 1878 Britain took control of Cyprus as a base for action against a Russian attack on the Ottoman Empire, after having taken part in the Crimean War 1854–56 and invading Afghanistan to forestall an increase in Russian influence there. Britain waged three bloody and unsuccessful wars in Afghanistan, as ferocious popular rebellions, invocations of jihad and inscrutable terrain frustrated British objectives. The First Anglo-Afghan War led to one of the most disastrous defeats of the Victorian military when an entire British army was wiped out by Russian-supplied Afghan Pashtun tribesmen during the 1842 retreat from Kabul. The Second Anglo-Afghan War led to the British debacle at Maiwand in 1880, the siege of Kabul and British withdrawal into India. The Third Anglo-Afghan War of 1919 stoked a tribal uprising against the exhausted British military on the heels of World War I and expelled the British permanently from the new Afghan state. The "Great Game" in Inner Asia ended with a bloody British expedition against Tibet in 1903–04.

At the same time, some powerful industrial lobbies and government leaders in Britain, later exemplified by Joseph Chamberlain, came to view formal empire as necessary to arrest Britain's relative decline in world markets. During the 1890s Britain adopted the new policy wholeheartedly, quickly emerging as the front-runner in the scramble for tropical African territories.

Britain's adoption of the New Imperialism may be seen as a quest for captive markets or fields for investment of surplus capital, or as a primarily strategic or pre-emptive attempt to protect existing trade links and to prevent the absorption of overseas markets into the increasingly closed imperial trading blocs of rival powers. The failure in the 1900s of Chamberlain's Tariff Reform campaign for Imperial protection illustrates the strength of free trade feeling even in the face of loss of international market share. Historians have argued that Britain's adoption of the "New imperialism" was an effect of her relative decline in the world, rather than of strength.

The evolution of colonialism in India should dissuade people from sweeping generalisations and over-simplifications regarding the roles of inter-capitalist competition and accumulated surplus in precipitating the era of the New Imperialism. Formal empire in India, beginning with the Government of India Act of 1858, was a means of consolidation, reacting to the abortive Indian Mutiny, which was in itself a conservative reaction among Indian traditionalists to British policy in the subcontinent.

British Colonial Policy

British colonial policy was always driven to a large extent by Britain's trading interests. While settler economies developed the infrastructure to support balanced development, some tropical African territories found themselves developed only as raw-material suppliers. British policies based on comparative advantage left many developing economies dangerously reliant on a single cash crop, with others exported to Britain or to overseas British settlements. A reliance upon the manipulation of conflict between ethnic, religious and racial identities, in order to keep subject populations from uniting against the occupying power — the classic "divide and rule" strategy — left a legacy of partition and/or inter-communal difficulties in areas as diverse as Ireland, India, Zimbabwe, Sudan, and Uganda.

Britain and the Scramble for Africa

Main article: Scramble for Africa.

In 1875 the two most important European holdings in Africa were French controlled Algeria and Britain's Cape Colony. By 1914 only Ethiopia and the republic of Liberia remained outside formal European control. The transition from an "informal empire" of control through economic dominance to direct control took the form of a "scramble" for territory by the nations of Europe. Britain tried not to play a part in this early scramble, being more of a trading empire rather than a colonial empire; however, it soon became clear it had to gain its own African empire to maintain the balance of power.

As French, Belgian and Portuguese activity in the lower Congo River region threatened to undermine orderly penetration of tropical Africa, the Berlin Conference of 1884–85 sought to regulate the competition between the powers by defining "effective occupation" as the criterion for international recognition of territorial claims, a formulation which necessitated routine recourse to armed force against indigenous states and peoples.

Britain's 1882 military occupation of Egypt (itself triggered by concern over the Suez Canal) contributed to a preoccupation over securing control of the Nile valley, leading to the conquest of the neighbouring Sudan in 1896–98 and confrontation with a French military expedition at Fashoda (September 1898).

In 1899 Britain completed her takeover of what is today South Africa. This had begun with the annexation of the Cape in 1795 and continued with the conquest of the Boer Republics in the late 19th century, following the Second Boer War. Cecil Rhodes was the pioneer of British expansion north into Africa with his privately owned British South Africa Company. Rhodes expanded into the land north of South Africa and established Rhodesia. Rhodes' dream of a railway connecting Cape Town to Alexandria passing through a British Africa covering the continent is what led to his company's pressure on the government for further expansion into Africa.

British gains in southern and East Africa prompted Rhodes and Alfred Milner, Britain's High Commissioner in South Africa, to urge a "Cape-to-Cairo" empire linking by rail the strategically important Canal to the mineral-rich South, though German occupation of Tanganyika prevented its realisation until the end of World War I. In 1903, the All Red Line telegraph system communicated with the major parts of the Empire.

Paradoxically Britain, the staunch advocate of free trade, emerged in 1914 with not only the largest overseas empire thanks to her long-standing presence in India, but also the greatest gains in the "scramble for Africa", reflecting her advantageous position at its inception. Between 1885 and 1914 Britain took nearly 30% of Africa's population under her control, compared to 15 % for France, 9 % for Germany, 7 % for Belgium and 1 % for Italy: Nigeria alone contributed 15 million subjects, more than in the whole of French West Africa or the entire German colonial empire.

Home Rule in white-settler colonies

Britain's empire had already begun its transformation into the modern Commonwealth with the extension of Dominion status to the already self-governing colonies of Canada (1867), Australia (1901), New Zealand (1907), Newfoundland (1907), and the newly-created Union of South Africa (1910). Leaders of the new states joined with British statesmen in periodic Colonial (from 1907, Imperial) Conferences, the first of which was held in London in 1887.

The foreign relations of the Dominions were still conducted through the Foreign Office of the United Kingdom: Canada created a Department of External Affairs in 1909, but diplomatic relations with other governments continued to be channelled through the Governors-General, Dominion High Commissioners in London (first appointed by Canada in 1880 and by Australia in 1910) and British legations abroad. Britain's declaration of war in World War I applied to all the Dominions.

But the Dominions did enjoy a substantial freedom in their adoption of foreign policy where this did not explicitly conflict with British interests: Canada's Liberal government negotiated a bilateral free-trade Reciprocity Agreement with the United States in 1911, but went down to defeat by the Conservative opposition.

In defence, the Dominions' original treatment as part of a single imperial military and naval structure proved unsustainable as Britain faced new commitments in Europe and the challenge of an emerging German High Seas Fleet after 1900. In 1909 it was decided that the Dominions should have their own navies, reversing an 1887 agreement that the then Australasian colonies should contribute to the Royal Navy in return for the permanent stationing of a squadron in the region.

The impact of the First World War

The aftermath of World War I saw the last major extension of British rule, with Britain gaining control through League of Nations Mandates in Palestine and Iraq after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East, as well as in the former German colonies of Tanganyika, South-West Africa (now Namibia) and New Guinea (the last two actually under South African and Australian rule respectively). The British zones of occupation in the German Rhineland after World War I and West Germany after World War II were not considered part of the Empire.

But although Britain emerged among the war's victors, and her rule expanded into new areas, the heavy costs of the war undermined her capacity to maintain the vast empire. The British had suffered millions of casualties and liquidated assets at an alarming rate, which led to debt accumulation, upending of capital markets and manpower deficiencies in the staffing of far-flung imperial posts in Asia and the African colonies. Nationalist sentiment grew in both old and new Imperial territories, fuelled by pride at Empire troops' participation in the war and the grievance felt by many non-white ex-servicemen at the racial discrimination they had encountered during their service to the Empire.

The 1920s saw a rapid transformation of Dominion status. Although the Dominions had had no formal voice in declaring war in 1914, each was included separately among the signatories of the 1919 peace Treaty of Versailles, which had been negotiated by a British-led united Empire delegation. In 1922 Dominion reluctance to support British military action against Turkey influenced Britain's decision to seek a compromise settlement.

Full Dominion independence was formalised in the 1926 Balfour Declaration and the 1931 Statute of Westminster: each Dominion was henceforth to be equal in status to Britain herself, free of British legislative interference and autonomous in international relations. The Dominions section created within the Colonial Office in 1907 was upgraded in 1925 to a separate Dominions Office and given its own Secretary of State in 1930.

Canada led the way, becoming the first Dominion to conclude an international treaty entirely independently (1923) and obtaining the appointment (1928) of a British High Commissioner in Ottawa, thereby separating the administrative and diplomatic functions of the Governor-General and ending the latter's anomalous role as the representative of the head of state and of the British Government. Canada's first permanent diplomatic mission to a foreign country opened in Washington, DC in 1927: Australia followed in 1940.

Egypt, formally independent from 1922 but bound to Britain by treaty until 1936 (and under partial occupation until 1956) similarly severed all constitutional links with Britain. Iraq, which became a British Protectorate in 1922, also gained complete independence ten years later in 1932.

The last colonial expansion of the British Empire was the Phoenix Islands Settlement Scheme, begun in 1938 and abandoned in 1963. The last territorial expansion of the British Empire was the annexation of Rockall to the west of the Outer Hebrides in 1955. The Royal Navy landed a party of seamen on the isle and officially claimed the rock in the name of the Queen. The action was prompted by the imminent intention of the Ministry of Defence to test launch a nuclear missile from the Outer Hebrides. It was feared that the heretofore unclaimed island might be used by the Soviet Union as a site for surveillance equipment. In 1972 the Isle of Rockall Act formally incorporated the island into the United Kingdom, although this was not accepted by the Republic of Ireland.

The end of British rule in Ireland

Despite Irish independence being guaranteed under the Third Irish Home Rule Act in 1914, the onset of World War I delayed its implementation. In 1919 Irish guerrillas, known as the Irish Republican Army under the leadership of Michael Collins began a military campaign against British rule. The ensuing Anglo-Irish War ended in 1921 with a stalemate and the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. The treaty divided Ireland into two states, most of the island (26 counties) became the Irish Free State, an independent dominion nation within the British Commonwealth, while the six counties in the north with a largely loyalist, Protestant community remained a part of the United Kingdom as Northern Ireland.

In 1948 Ireland became a republic, fully independent from the United Kingdom, and withdrew from the Commonwealth. Ireland's Constitution claimed the six counties of Northern Ireland as a part of the Republic of Ireland until 1998. The issue over whether Northern Ireland should remain in the United Kingdom or join the Republic of Ireland has divided Northern Ireland's people and led to a long and bloody conflict known as the Troubles.

However the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 brought about a ceasefire between most of the major organisations on both sides, creating hope for a peaceful resolution.

Decolonisation and Decline

The rise of anti-colonial nationalist movements in the subject territories and the changing economic situation of the world in the first half of the 20th century challenged an imperial power now increasingly preoccupied with issues nearer home. The Empire's end began with the onset of the Second World War, when a deal was reached between the British government and the Indian independence movement, whereby the Indians would co-operate and remain loyal during the war, after which they would be granted independence. Following India's lead, nearly all of Britain's other colonies would become independent over the next two decades.

The end of Empire gathered pace after Britain's efforts during World War II left the country all but exhausted and found its former allies disinclined to support the colonial status quo. Economic crisis in 1947 made many realise that the Labour government of Clement Attlee should abandon Britain's attempt to retain all of its overseas territories. The Empire was increasingly regarded as an unnecessary drain on public finances by politicians and civil servants, if not the general public.

Britain's declaration of hostilities against Germany in September 1939 did not automatically commit the Dominions. All the Dominions except Australia and Ireland issued their own declarations of war. The Irish Free State had negotiated the removal of the Royal Navy from the Treaty Ports the year before, and chose to remain legally neutral throughout the war. Australia went to war under the British declaration.

World War II fatally undermined Britain's already weakened commercial and financial leadership and heightened the importance of the Dominions and the United States as a source of military assistance. Australian prime minister John Curtin's unprecedented action (1942) in successfully demanding the recall for home service of Australian troops earmarked for the defence of British-held Burma demonstrated that Dominion governments could no longer be expected to subordinate their own national interests to British strategic perspectives. Curtin had written in a national newspaper the year before that Australia should look to the United States for protection, rather than Britain.

After the war, Australia and New Zealand joined with the United States in the ANZUS regional security treaty in 1951 (although the US repudiated its commitments to New Zealand following a 1985 dispute over port access for nuclear vessels). Britain's pursuit (from 1961) and attainment (1973) of European Community membership weakened the old commercial ties to the Dominions, ending their privileged access to the UK market.

In the Caribbean, Africa, Asia and the Pacific, post-war decolonisation was accomplished with almost unseemly haste in the face of increasingly powerful (and sometimes mutually conflicting) nationalist movements, with Britain rarely fighting to retain any territory. Britain's limitations were exposed to a humiliating degree by the Suez Crisis of 1956 in which the United States opposed Anglo-French intervention in Egypt, seeing it as a doomed adventure likely to jeopardise American interests in the Middle East.

The independence of India in 1947 ended a 40-year struggle by the Indian National Congress, firstly for self-government and later for full sovereignty, though the land's partition into India and Pakistan entailed violence costing hundreds of thousands of lives. The acceptance by Britain, and the other Dominions, of India's adoption of republican status (1949) is now taken as the start of the modern Commonwealth.

Singapore became independent in two stages. The British did not believe that Singapore would be large enough to defend itself against others alone. Therefore, Singapore was joined with Malaya, Sarawak and North Borneo to form Malaysia upon independence from the Empire. This short-lived union was dissolved in 1965 when Singapore left Malaysia and achieved complete independence.

Burma achieved independence (1948) outside the Commonwealth; Burma being the first colony to sever all ties with the British; Ceylon (1948) and Malaya (1957) within it. Britain's Palestine Mandate ended (1948) in withdrawal and open warfare between the territory's Jewish and Arab populations. In the Mediterranean, a guerrilla war waged by Greek Cypriot advocates of union with Greece ended (1960) in an independent Cyprus, although Britain did retain two military bases - Akrotiri and Dhekelia.

The end of Britain's Empire in Africa came with exceptional rapidity, often leaving the newly-independent states ill-equipped to deal with the challenges of sovereignty: Ghana's independence (1957) after a ten-year nationalist political campaign was followed by that of Nigeria (1960), Sierra Leone and Tanganyika (1961), Uganda (1962), Kenya and Zanzibar (1963), The Gambia (1965), Botswana (formerly Bechuanaland) and Lesotho (formerly Basutoland) (1966) and Swaziland (1968).

British withdrawal from the southern and eastern parts of Africa was complicated by the region's white settler populations: Kenya had already provided an example in the Mau Mau Uprising of violent conflict exacerbated by white landownership and reluctance to concede majority rule. White minority rule in South Africa remained a source of bitterness within the Commonwealth until the ending of apartheid policy in 1994.

Although the white-dominated Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland ended in the independence of Malawi (formerly Nyasaland) and Zambia (the former Northern Rhodesia) in 1964, Southern Rhodesia's white minority (a self-governing colony since 1923) declared independence with their UDI rather than submit to equality with black Africans. The support of South Africa's apartheid government kept the Rhodesian regime in place until 1979, when agreement was reached on majority rule in an independent Zimbabwe.

Most of Britain's Caribbean territories opted for eventual separate independence after the failure of the West Indies Federation (1958–62): Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago (1962) were followed into statehood by Barbados (1966) and the smaller islands of the eastern Caribbean (1970s and 1980s). Britain's Pacific dependencies underwent a similar process of decolonisation in the latter decades. At the end of Britain's 99-year lease of the mainland New Territories, Hong Kong became a Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China in 1997.

References

Overviews

- Bryant, Arthur, The History of Britain and the British Peoples, 3 vols. (London, 1984–90).

- Judd, Denis, Empire: The British Imperial Experience, From 1765 to the Present (London, 1996).

- T. O. Lloyd; The British Empire, 1558-1995 Oxford University Press, 1996

- Louis, William. Roger (general editor), The Oxford History of the British Empire, 5 vols. (Oxford, 1998–99).

- Marshall, P. J. (ed.), The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire (Cambridge, 1996).

- James S. Olson and Robert S. Shadle; Historical Dictionary of the British Empire 1996

- Rose, J. Holland, A. P. Newton and E. A. Benians (gen. eds.), The Cambridge History of the British Empire, 9 vols. (Cambridge, 1929–61).

- Simon C. Smith. British Imperialism 1750-1970 Cambridge University Press, 1998. brief

Specialized scholarly studies

- Adams, James Truslow, 'On the Term “British Empire”', American Historical Review, 27 (1922), 485–9.

- Andrews, Kenneth R., Trade, Plunder and Settlement: Maritime Enterprise and the Genesis of the British Empire, 1480–1630 (Cambridge, 1984).

- David Armitage; The Ideological Origins of the British Empire Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Armitage, David, 'Greater Britain: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis?' American Historical Review, 104 (1999), 427–45.

- Armitage, David (ed.), Theories of Empire, 1450–1800 (Aldershot, 1998).

- Charles A. Barone, Marxist Thought on Imperialism: Survey

and Critique (London: Macmillan, 1985)

- Bernard Bailyn and Philip D. Morgan (eds.), Strangers within the Realm: Cultural Margins of the First British Empire (Chapel Hill, 1991)

- Barker, Sir Ernest, The Ideas and Ideals of the British Empire (Cambridge, 1941).

- W. Baumgart, Imperialism: The Idea and Reality of British and French Colonial Expansion, 1880-1914 (Oxford University

Press, 1982)

- Beer, G. L., The Origins of the British Colonial System 1578–1660 (London, 1908).

- Bennett, George (ed. ), The Concept of Empire: Burke to Attlee, 1774–1947 (London, 1953).

- J. M. Blaut, The Colonizers' Model of the World, London 1993

- Philip Darby, The Three Faces of Imperialism:British and American Approaches to Asia and Africa, 1870-1970 (Yale University Press, 1987

- Harlow, V. T., The Founding of the Second British Empire, 1763–1793, 2 vols. (London, 1952–64).

- Edward Ingrain. The British Empire as a World Power (2001)

- Robert Johnson. British Imperialism Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. historiography

- Kennedy, Paul, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery (London, 1976).

- Knorr, Klaus E., British Colonial Theories 1570–1850 (Toronto, 1944).

- Mehta, Uday Singh, Liberalism and Empire: A Study in Nineteenth-Century British Liberal Thought (Chicago, 1999).

- Pocock, J. G. A., 'The Limits and Divisions of British History: In Search of the Unknown Subject', American Historical Review, 87 (1982), 311–36.

Extent

At what is usually considered its height in 1921, the British Empire consisted of the following territories:

Africa

- Basutoland (now Lesotho)

- Bechuanaland (now Botswana) (divided, one part colony and another part a British protectorate)

- British Togoland (now part of Ghana, a League of Nations Mandate)

- Gambia

- Gold Coast (now Ghana)

- Egypt (as a state under British protectorate)

- Kenya (most parts colony, the coast area protectorate)

- Mauritius

- Nigeria

- Northern Cameroons (now part of Nigeria, a League of Nations Mandate)

- Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia)

- Nyasaland (now Malawi)

- Seychelles

- Sierra Leone

- Somaliland

- South Africa (a self-governing Dominion, formed by the union in 1910 of the four colonies of Cape Colony, Natal, Transvaal, and the Orange River Colony)

- Southern Cameroons (now part of Cameroon, comprising 9% of the territory of Cameroon; a League of Nations Mandate)

- Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe)

- South West Africa (now Namibia, a League of Nations mandate of South Africa)

- Swaziland (as a state under British protectorate)

- Sudan (held in condominium with the Egyptian government)

- Tanganyika (now Tanzania, a League of Nations Mandate)

- Uganda

- Zanzibar (now Tanzania) (as a state under British protectorate)

The Americas and Atlantic

- Ascension Island

- Bermuda

- Canada (formed in 1867 by the union of the colonies of United Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia; later joined by British Columbia, Prince Edward Island, and receiving the territory of the Hudson's Bay Company colony of Rupert's Land)

- Falkland Islands

- Newfoundland (a self-governing dominion, now a province of Canada)

- West Indies

- Bahamas

- Barbados

- British Guiana (now Guyana)

- British Honduras (now Belize)

- Jamaica (including the Cayman Islands and the Turks and Caicos Islands)

- Leeward Islands, including

- Trinidad (including Tobago)

- Windward Islands, including

- St Helena

- Tristan da Cunha

- South Georgia (also claimed by Argentina)

Antarctica

- British Antarctic Territory (under Antarctic Treaty overlaps Argentine and Chilean claim)

Asia

- Aden Colony (now part of Yemen)

- Aden Protectorate (states under British protection; now part of Yemen)

- Bahrain (a protectorate)

- Bhutan (a protectorate)

- Brunei (a protectorate)

- Ceylon (now Sri Lanka)

- Hong Kong (now a Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China after ceded by China in 1841,1860 and leased in 1898)

- India (now India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar - this included both provinces under direct British rule, and the Princely States, protectorates under native princes)

- Iraq (a League of Nations Mandate)

- Kuwait (a protectorate)

- Malaya (a protectorate, now Peninsular Malaysia, part of Malaysia)

- Maldives

- North Borneo (a protectorate, now Sabah, part of Malaysia)

- Muscat and Oman (a protectorate, now Oman)

- Palestine (a League of Nations Mandate, now Israel (excluding the Golan Heights), the Gaza Strip and the West Bank)

- Qatar (a protectorate)

- Sarawak (a protectorate, now part of Malaysia)

- Sikkim (a protectorate, now part of India)

- Straits Settlements (Singapore, Malacca, Penang, and Labuan in Southeast Asia and Cocos Islands and Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean; now divided among Singapore, Malaysia, and Australia)

- Transjordan (now Jordan)

- Trucial States (states under British protection; now the United Arab Emirates)

- Wei-Hai-Wei (威海衞) (Now the city of Weihai in Shandong, China)

- There were also several extraterritorial territories in China called treaty ports, the most famous being the British concession in Shanghai

Europe and the Mediterranean

- Channel Islands (crown dependencies)

- Cyprus (a protectorate until 1914)

- Gibraltar

- Malta

- Isle of Man (crown dependency)

- United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The Ionian Islands had also been a British protectorate until 1864.

Pacific

- Australia (a self-governing Dominion, having been formed in 1901 by the merger of the previous colonies of New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria, and Western Australia)

- British New Guinea (southern part of what is now Papua New Guinea)

- Fiji

- Gilbert and Ellice Islands (now Kiribati, Tuvalu, and Tokelau)

- Nauru (a League of Nations Mandate of Australia)

- Territory of New Guinea (now northern Papua New Guinea, a League of Nations Mandate of Australia)

- New Hebrides (condominium shared with the French Empire) (now Vanuatu)

- New Zealand (a self-governing Dominion)

- Papua (now southern Papua New Guinea, an Australian territory)

- Pitcairn

- Samoa (a League of Nations Mandate of New Zealand)

- Solomon Islands

- Tonga (as a state under British protectorate)

Extent after World War II

During and after World War II Britain acquired control of further territories though most of these (except the Trust Territories) cannot be considered part of the British Empire as control was subject to international agreements. Territories obtained during and after the war were controlled in a variety of ways, with some ruled as UN Trust Territories and others being totally occupied and administered, while still others were only militarily occupied and the local administrations allowed to continue. These territories were:

Africa

- Comoros (as part of Madagascar, see below)

- Eritrea (as a UN Trust Territory)

- French Somaliland (now Djibouti) (occupied, local administration continues)

- Italian Somaliland (occupied and administered until 1950, then returned to Italy as a UN Trust Territory).

- Madagascar (occupied and administered)

- Mayotte (as part of the Comoros, see above)

- Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (now most of Libya) (as a UN Trust Territory)

- Reunion (occupied, local administration continues)

The Americas and Atlantic

- Aruba (as part of the Netherlands Antilles, see below)

- Netherlands Antilles (as a protectorate)

Asia

- Dutch East Indies- mainly just Java and Sumatra (occupied and administered by South East Asia Command (SEAC) to accept Japanese surrender and restore law and order until the Dutch arrived)

- French Indochina- south of the 16th parallel, but mainly Saigon (occupied and administered by SEAC to accept Japanese surrender and restore law and order until the French arrived)

- Iran (occupied and administered by Indian Command)

- Iraq (under same administration as Iran)

- Japan (Shikoku and part of Honshu occupied as British Commonwealth Occupation Zone)

- Lebanon (occupied and administered)

- Syria (same administration as Lebanon)

Europe

- Austria (occupied south-eastern Austria as British Occupation Zone)

- Faeroe Islands (occupied and administered, but local administration continues)

- Germany (occupied north-western Germany as British Occupation Zone)

- Italy (temporary military government and occupation, except in Udine and Venezia Gulia provinces)

Territories Lost by British Empire before 1921

Americas and Oceania

- Thirteen Colonies, later the United States of America

- Delaware

- Maryland

- New Jersey

- Virginia, later Virginia and West Virginia

- Massachusetts, later Massachusetts and Maine

- New York, later New York and Vermont

- New Hampshire

- Rhode Island

- Georgia

- North Carolina

- Roanoke, later part of North Carolina

- South Carolina

- Connecticut

- Pennsylvania

- Northwest Territory between the 13 Colonies and the Mississippi River, with conflicting claims between the Colonies, which is now Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Wisconsin, as well as part of Minnesota.

- Territory between the 13 Colonies and the Mississippi south of the Ohio River, with conflicting claims, which is now Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Kentucky and part of Louisiana.

- Suriname from 1650 until 1667 when it was traded to the Dutch in exchange for New Amsterdam (now New York).

- East Florida and West Florida, from 1763 to 1783; to Spain, but later in the United States.

- Part of the Oregon Country (which was disputed with the USA, Spain, and Russia) until 1846, to the United States.

- Hawaii (the Sandwich Islands) ceded to Britain on 25 February 1843; gained Independence 28 November 1843; annexed by the United States on 7 July 1898.

- Havana and de facto Cuba was occupied and captured by the British in 1762 during the Seven Years' War, but were never annexed.

- The Mosquito Coast was a British protectorate from 1655 to 1850.

- Samana, a city on the northeast coast of the now Dominican Republic, occupied from July to August 1809

- St. Dominique, now Haiti, mainly the coastal areas around Port-au-Prince from just north of the city to the south and west and including the towns of Leogane and Petit Goave. Other towns and areas in the French colony occupied by the British from 1793-1798 (Revolutionary Wars) included Tiburon, Jérémie, Mole St. Nicholas, St. Marc and Tortuga Island just off the northern coast of Haiti.

Europe

- Helgoland seized by the British in 1807 ceded to Germany in 1890.

- The Ionian Islands were captured by the British (from the Ottoman empire) in 1809 and ceded to Greece in 1864.

- Minorca was first captured by the British in 1708; it was formally ceded to Spain in 1802.

Asia and Africa

- Afghanistan was annexed a few times into the British Empire from the Anglo-Afghan Wars. Afghanistan achieved independence in 1919, after the Third Anglo-Afghan War.

- Manila was occupied by the British during the Seven Years' War, from 1762 to 1763.

- Bencoolen, a trading post in the Dutch East Indies.

- Senegal was annexed two times into the British colonial empire. First from 1758 to 1779 and in 1809 to 1817.

Remaining Overseas Territories

Main article: British overseas territory.

Now only a few small territories remain under British administration, mostly for reasons of perceived insufficiency as sovereign states. The last remaining Overseas Territories are:

Overseas Territories possessing substantial self-government

- Anguilla

- Bermuda

- British Virgin Islands

- Cayman Islands

- Gibraltar

- Montserrat

- Turks and Caicos Islands

Other Overseas Territories

- British Antarctic Territory (under Antarctic Treaty overlaps Argentine and Chilean claim)

- British Indian Ocean Territory

- Falkland Islands (also claimed by Argentina)

- Pitcairn Island

- Saint Helena (including dependencies of Ascension and Tristan da Cunha)

- South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (also claimed by Argentina)

- Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia

Crown Dependencies in British Isles (Outside UK & EU)

Kingdom of England (927 - 1707)

- Norway from 1016 to 1035

- Denmark from 1016 to 1035 and again from 1040 to 1042

- Normandy from 1066 to 1087 and again from 1106 to 1204/1259

- Anjou from 1153 to 1204

- Aquitaine from 1153 to 1362, from 1377 to 1390, and again from 1399 to 1449

- Lordship of Ireland from 1171 to 1541

- Principality of Wales from 1282 to 1535-1542 (when Wales and England were united in the Acts of Union)

- Kingdom of Ireland from 1541 to 1707

- Scotland from 1603 to 1707 (when they were joined together in the Kingdom of Great Britain)

- Netherlands from 1689 to 1702, with the Stadtholder of the Netherlands also serving as King of England, Scotland and Ireland.Only 2 Dutch provinces never entered into the personal union: Friesland and Groningen.

Kingdom of Scotland (843 - 1707)

- Personal union with England and Ireland from 1603 to 1707 (when England and Scotland were joined together in the Kingdom of Great Britain)

- Personal union with the Netherlands from 1689 to 1702, with the Stadtholder of most of the provinces of the Netherlands also serving as King of Scotland, England and Ireland. The actual situation was slightly more complex with the Dutch provinces Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht entering into personal union in 1672, Gelderland and Overijssel in 1675 and Drenthe in 1696. Only 2 Dutch provinces never entered into the personal union: Friesland and Groningen.

Kingdom of Great Britain (1707 - 1801)

- Ireland from 1707 to 1801 (when they were joined together in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland)

- Hanover from 1714 to 1801

- Corsica from 1794 to 1796

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1801 - 1927)

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (1927 - present)

Former

- Ireland - 1927 to 1949

- India - 1927 to 1950

- Union of South Africa - 1931 to 1961

- Pakistan - 1947 to 1956

- Ceylon now Sri Lanka - 1948 to 1972

- Ghana - 1957 to 1960

- Sierra Leone - 1961 to 1971

- Nigeria - 1960 to 1963

- Tanganyika now Tanzania - 1961 to 1962

- Uganda - 1962 to 1963

- Trinidad and Tobago - 1962 to 1976

- Kenya - 1963 to 1964

- Malawi - 1964 to 1966

- Malta - 1964 to 1974

- Gambia - 1965 to 1970

- Guyana - 1966 to 1970

- Mauritius - 1968 to 1992

- Fiji - 1970 to 1987

Current

- Canada, through the Statute of Westminster in 1931

- Australia, through adoption of the Statute of Westminster in 1942 (retroactive to 1939)

- New Zealand, through adoption of the Statute of Westminster in 1947

- Jamaica, through independence in 1962

- Barbados, through independence in 1966

- The Bahamas, through independence in 1973

- Grenada, through independence in 1974

- Papua New Guinea, through independence in 1975

- The Solomon Islands, through independence in 1978

- Tuvalu, through independence in 1978

- Saint Lucia, through independence in 1979

- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, through independence in 1979

- Antigua and Barbuda, through independence in 1981

- Belize, through independence in 1981

- Saint Kitts and Nevis, through independence in 1983

See also

- Tudor re-conquest of Ireland

- British colonisation of the Americas

- British East India Company

- British Empire and Commonwealth Museum

- Commonwealth of Nations

- Commonwealth Realm

- Decolonisation

- Empire Day

- Evolution of the British Empire

- History of the United Kingdom

- Imperialism in Asia

- List of United Kingdom topics

- "The White Man's Burden"

- Size of Empires

- Government Houses of the British Empire

External links

- Extensive information on the British Empire

- Sizes of various empires and quasi-empires

- The Untold Story of the Savage Battle for British and Indian Control of the Ohio Country.

Further reading

- James, Lawrence,(1998) The Rise and Fall of the British Empire, 2nd. ed, Abacus ISBN 031216985X

- Judd, Denis, (1999) Empire: The British Imperial Experience from 1765 to the Present, Fontana ISBN 0465019544

- Fergusson, Niall (2003). Empire – How Britain Made the Modern World, Pengiun Books ISBN 0-141-00754-0

- Fitzpatrick, Alan, (2004) Wilderness War on the Ohio, 2nd Ed., Fort Henry Publications ISBN 977614700