Union (American Civil War): Difference between revisions

→Congress: Lincoln's role |

→Draft riots: Ohio |

||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

====Draft riots==== |

====Draft riots==== |

||

Discontent with the 1863 [[Conscription in the United States#Early drafts|draft]] law led to riots in several cities and in rural areas as well, By far the most important were the [[New York City draft riots]] of July 13 to July 16, 1863.<ref>Barnet Schecter, ''The Devil's Own Work: The Civil War Draft Riots and the Fight to Reconstruct America'' (2005)</ref> Irish Catholic and other workers fought police, militia and regular army units until the Army used artillery to sweep the streets. Initially focused on the draft, the protests quickly expanded into violent attacks on blacks in New York City, with many killed on the streets.<ref>[http://www.press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/317749.html The New York City Draft Riots] ''In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City'', 1626-1863, by Leslie M. Harris</ref> |

Discontent with the 1863 [[Conscription in the United States#Early drafts|draft]] law led to riots in several cities and in rural areas as well, By far the most important were the [[New York City draft riots]] of July 13 to July 16, 1863.<ref>Barnet Schecter, ''The Devil's Own Work: The Civil War Draft Riots and the Fight to Reconstruct America'' (2005)</ref> Irish Catholic and other workers fought police, militia and regular army units until the Army used artillery to sweep the streets. Initially focused on the draft, the protests quickly expanded into violent attacks on blacks in New York City, with many killed on the streets.<ref>[http://www.press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/317749.html The New York City Draft Riots] ''In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City'', 1626-1863, by Leslie M. Harris</ref> |

||

Small-scale riots broke out in ethnic German and Irish districts, and in aereas along the Ohio River with many Copperheads. [[Holmes County, Ohio]] was an isolated localistic areas dominated by [[Pennsylvania Dutch]] and some recent German immigrants. It was a Democratic stronghold and few men dared speak out in favor of conscription. Local politicians denounced Lincoln and Congress as despotic, seeing the draft law as a violation of their local autonomy. In June 1863, small scale disturbance broke out; they ended when the Army send in armed units.<ref>Kenneth H. Wheeler, "Local autonomy and civil war draft resistance: Holmes County, Ohio," ''Civil War History,'' June 1999, Vol. 45 Issue 2, pp 147-58 </ref> |

|||

==Economy== |

==Economy== |

||

Revision as of 23:55, 24 October 2011

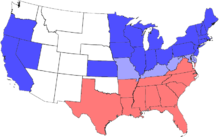

During the American Civil War, the Union was a name used to refer to the federal government of the United States, which was supported by the twenty free states and five border slave states. It was opposed by 11 Southern slave states that had declared a secession to join together to form the Confederacy. Although the Union states included the Western states of California, Oregon, and (after 1864) Nevada, as well as states generally considered to be part of the Midwest, the Union has been also often loosely referred to as "the North", both then and now.[1]

Overview

Legally, the term originated in the Perpetual Union of the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union. Also, then and now, in the public dialogue of the United States, new states have been "admitted to the Union", and the President's annual address to Congress and to the people has been referred to as the "State of the Union address". Even before the war started, the phrase "preserve the Union" was commonplace and a "union of states" had been used to refer to the entire United States. Using the term "Union" to apply to the non-secessionist side carried a connotation of legitimacy as the continuation of the pre-existing political entity.[2]

Unionists in South and Border states

People loyal to the federal government and opposed to secession living in the border states (where slavery was legal in 1861) and Confederate states were termed Unionists. Confederates sometimes styled them "Homemade Yankees". However, Southern Unionists were not necessarily northern sympathizers and many of them– although opposing secession– supported the Confederacy once it was a fact.

Still, nearly 120,000 Southern Unionists served in the Union Army during the Civil War, and Unionist regiments were raised in every Southern state. Southern Unionists were extensively used as anti-guerrilla forces and as occupation troops in areas of the Confederacy occupied by the Union. Since the Civil War, the term "Northern" has been a widely used synonym for the Union side of the conflict. Union is usually used in contexts where "United States" might be confusing, "Federal" obscure, or "Yankee" dated or derogatory.

Size and strength

In comparison to the Confederacy, the Union was heavily industrialized and far more urbanized than the rural South. The Union states had nearly five times the white population of the Confederate states (23 million to 5 million). The Union's great advantages in population and industry would prove to be vital long-term factors in its victory over the Confederacy..

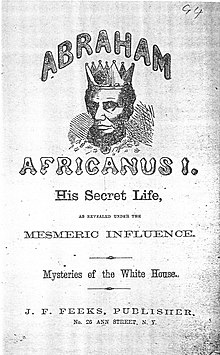

Presidency

Lincoln, an ungainly giant, did not look the part of a president, but historians have overwhelmingly praised the "political genius" of his his performance in the role.[3] His first priority was military victory, and that required that he master entirely new skills as a master strategist and diplomat. He supervised not only the supplies and finances, but as well the manpower, the selection of generals, and the course of overall strategy. Working closely with state and local politicians he rallied public opinion and (at Gettysburg) articulated a national mission that has defined America ever since. Lincoln's charm and willingness to cooperate with political and personal enemies made Washington work much more smoothly than Richmond. His wit smoothed many rough edges. Lincoln's cabinet proved much stronger and more efficient than Davis's, as Lincoln channeled personal rivalries into a competition for excellence rather than mutual destruction. With William Seward at State, Salmon P. Chase at the Treasury, and (from 1862) Edwin Stanton at the War Department, Lincoln had a powerful cabinet of determined men; except for monitoring major appointments, Lincoln gave them full reign to destroy the Confederacy.[4]

Congress

The Republican Congress passed many major laws that reshaped the nation's economy, financial system, tax system, land system, and higher education system. including the Morrill tariff, the Homestead Act, the Pacific Railroad Act, and the National Banking Act.[5] Lincoln paid relatively little attention to this legislation as he focused on war issues, but he worked smoothly with powerful Congressional leaders such as Thaddeus Stevens (on taxation and spending), Charles Sumner (on foreign affairs), Lyman Trumbull (on legal issues), Justin Smith Morrill (on land grants and tariffs) and William Pitt Fessenden (on finances).[6]

Military and Reconstruction issues were another matter, and Lincoln as the leader of the moderate and conservative factions of the Republican Party often crossed swords with the Radical Republicans, led by Stevens abd Sumner. Tap shows that Congress challenged Lincoln's role as commander-in-chief through the the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. It was a joint committee of both houses that was dominated by Radicals who took a hard line against the Confederacy. During the 37th and 38th Congresses, it investigated every aspect of Union military operations, with special attention to finding the men guilt of military defeats. They assumed an inevitable Union victory, and failure seemed to them to indicate evil motivations or personal failures. They were skeptical of military science and especially the graduates of the US Military Academy at West Point, many of alumni of which were leaders of the enemy army. They much preferred political generals with a known political record. Some committee suggested that West Pointers who engaged in strategic maneuver were cowardly or even disloyal. It ended up endorsing incompetent but politically correct generals.[7]

Politics

Opposition

The main opposition came from Copperheads, who were Southern sympathizers in the Midwest. Irish Catholics after 1862 opposed the war, and rioted in the New York Draft Riots of 1863. The Democratic Party was deeply split. In 1861 most Democrats supported the war, but with the growth of the Copperhead movement, the party increasingly split down the middle. It scored major gains in the 1862 elections, including the election of moderate Horatio Seymour as governor of New York. They gained 28 seats in the House, but remained a minority. Indiana was especially hard-fought, but when the Democrats gained control of the legislature in the 1862 election they were unable to impede the war effort, which was controlled by governor Oliver P. Morton with federal help.[8]

The Democrats nominated George McClellan a War Democrat in 1864 but gave him an anti-war platform. In terms of Congress the opposition was nearly powerless--and indeed in most states. In Indiana and Illinois pro-war governors circumvented anti-war legislatures elected in 1862. For 30 years after the war the Democrats carried the burden of having opposed the martyred Lincoln, the salvation of the Union and the destruction of slavery.[9]

Copperheads

The Copperheads were a large faction of northern Democrats who opposed the war, demanding an immediate peace settlement. The said they wanted to restore "the Union as it was" (that is, with the South and with slavery), but they realized that the Confederacy would never volunarily rejoin the U.S. The most prominent Copperhead was Ohio's Clement L. Vallandigham, a Congressman and leader of the Democratic Party in Ohio. He was defeated in an intense election for governor in 1863. In Republican prosecutors in the Midwest accused some Copperhead activists of treason in a series of trials in 1864.[10]

Copperheadism was a grassroots movement, strongest in the area just north of the Ohio River, as well as some urban ethnic wards. Some historians have argued that it represented a traditionalistic element alarmed at the rapid modernization of society sponsored by the Republican Party. It looked back to Jacksonian Democracy for inspiration. Weber (2006) argues that the Copperheads damaged the Union war effort by fighting the draft, encouraging desertion, and forming conspiracies.[11] However other historians say the Copperheads were a legitimate opposition force unfairly treated by the government, adding that the draft was in disrepute and that the Republicans greatly exaggerated the conspiracies for partisan reasons.[12] Copperheadism was a major issue in the 1864 presidential election; its strength waxed when Union armies were doing poorly, and waned when they won great victories. After the fall of Atlanta in September 1864 military success seemed assured, and Copperheadism collapsed.

Conscription

Draft riots

Discontent with the 1863 draft law led to riots in several cities and in rural areas as well, By far the most important were the New York City draft riots of July 13 to July 16, 1863.[13] Irish Catholic and other workers fought police, militia and regular army units until the Army used artillery to sweep the streets. Initially focused on the draft, the protests quickly expanded into violent attacks on blacks in New York City, with many killed on the streets.[14]

Small-scale riots broke out in ethnic German and Irish districts, and in aereas along the Ohio River with many Copperheads. Holmes County, Ohio was an isolated localistic areas dominated by Pennsylvania Dutch and some recent German immigrants. It was a Democratic stronghold and few men dared speak out in favor of conscription. Local politicians denounced Lincoln and Congress as despotic, seeing the draft law as a violation of their local autonomy. In June 1863, small scale disturbance broke out; they ended when the Army send in armed units.[15]

Economy

The Union economy grew and prospered during the war while fielding a very large army and navy. The Republicans in Washington had a Whiggish vision of an industrial nation, with great cities, efficient factories, productive farms, national banks, and high speed rail links. The South had resisted policies such as tariffs to promote industry and homestead laws to promote farming because slavery would not benefit; with the South gone, and Northern Democrats very weak in Congress, the Republicans enacted their legislation. At the same time they passed new taxes to pay for part of the war, and issued large amounts of bonds to pay for the most of the rest. (The remainder can be charged to inflation.) They wrote an elaborate program of economic modernization that had the dual purpose of winning the war and permanently transforming the economy.[16]

Financing the war

The United States needed $3 billion to pay for the immense armies and fleets raised to fight the Civil War — over $400 million just in 1862. The chief source of Federal revenue had been the tariff revenues. Therefore Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, though a long-time free-trader, worked with Morrill to pass a second tariff bill in summer 1861, raising rates another 10 points in order to generate more revenues.[17] These subsequent bills were primarily revenue driven to meet the war's needs, though they enjoyed the support of protectionists such as Carey, who again assisted Morrill in the bill's drafting.

The Morrill Tariff of 1861 was designed to raise revenue. The tariff act of 1862 served not only to raise revenue, but also to encourage the establishment of factories free from British competition by taxing British imports. Furthermore, it protected Americvan factory workers from low paid European workers, and as a major bonus attracted tens of thousands of those Europeans to immigrate to America for high wage factory and craftsman jobs.[18]

However, the tariff played only a modest role in financing the war. It was far less important than other measures, such as $2.8 billion in bond sales and some printing of Greenbacks. Customs revenue from tariffs totaled $345 million from 1861 through 1865, or 43% of all federal tax revenue, while spending on the Army and Navy totalled $3,065 million.[19]

Land grants

The U.S. government owned vast amounts of good land (mostly from the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 and the Oregon Treaty with Britain in 1846). The challenge was to make the land useful to people and to provide the economic basis for the wealth that would pay off the war debt. Land grants went to railroad construction companies to open up the western plains and link up to California. Together with the free lands provided farmers by the Homestead Law the low-cost farm lands provided by the land grants speeded up the expansion of commercial agriculture. The North's most important war measure was perhaps the creation of a system of national banks that provided a sound currency for the industrial expansion. Even more important, the hundreds of new banks that were allowed to open were required to purchase government bonds. Thereby the nation monetized the potential wealth represented by farms, urban buildings, factories, and businesses, and immediately turned that money over to the Treasury for war needs.

The 1862 Homestead Act opened up the public domain lands for free. Land grants to the railroads meant they could sell tracts for family farms (80 to 200 acres) at low prices with extended credit. In addition the government sponsored fresh information, scientific methods and the latest techniques through the newly established Department of Agriculture and the Morrill Land Grant College Act.

Agriculture

Agriculture was the largest single industry and it prospered during the war.[20] Prices were high, pulled up by a strong demand from the army and from Britain (which depended on American wheat for a fourth of its food imports.) The war acted as a catalyst which encouraged the rapid adoption of horse-drawn machinery and other implements. The rapid spread of recent inventions such as the reaper and mower made the work force efficient, even as hundreds of thousands of farmers were in the army. Many wives took their place, and often consulted by mail on what to do; increasingly they relied community and extended kin for advice and help.[21]

Society

Religion

Religion was a powerful force and no church was more active in supporting the Union than the Methodist Episcopal Church. For example its magazine Ladies' Repository promoted Christian family activism. Its articles provided moral uplift to women and children. It portrayed the War as a great moral crusade against a decadent Southern civilization corrupted by slavery. It recommended activities that family members could perform in order to aid the Union cause.[22]

Family

Frank reports that what it meant to be a father varied with status and age, but most men demonstrated dual commitments as providers and nurturers and also believed that husband and wife had mutual obligations toward their children. The war privileged masculinity, dramatizing and exaggerating, father-son bonds. Especially at five critical five stages in the soldier's career (enlistment, blooding, mustering out, wounding, and death) letters from absent fathers articulated a distinctive set of 19th-century ideals of manliness.[23]

Children

There were numerous children's magazines such as Merry's Museum, The Student and Schoolmate, Our Young Folks, The Little Pilgrim, Forrester's Palymate, and The Little Corporal. They showed a Protestant religious tone and "promoted the principles of hard work, obedience, generosity, humility, and piety; trumpeted the benefits of family cohesion; and furnished mild adventure stories, innocent entertainment, and instruction."[24] Their pages featured factual information and anecdotes about the war along with related quizzes, games, poems and songs, short oratorical pieces for "declamation," short stories, and very short plays that children could stage. They promoted patriotism and the Union war aims, fostered kindly attitudes toward freed slaves, blackened the Confederates cause, encouraged readers to raise money for war-related humanitarian funds, and dealt with the death of family members.[25] By 1866 Milton Bradley Company was selling "The Myriopticon: A Historical Panorama of the Rebellion" that allowed children to stage a neighborhood show that would explain the war. It comprised colorful drawings that were turned on wheel and included pre-printed tickets, poster advertisements, and narration that could be read aloud at the show.[26]

Caring for war orphans was an important function for local organizations as well as state and local government.[27] A typical state was Iowa, where the private "Iowa Soldiers Orphans Home Association" operated with funding from the legislature and and public donations. It set up orphanages in Davenport, Glenwood and Cedar Falls. The state government funded pensions for the widows and children of soldiers.[28]

All the northern states had free public school systems before the war, but not the border states. West Virginia set up its system in 1863. Over bitter opposition it established an almost-equal education for black children, most of whom were ex-slaves.[29] Thousands of black refugees poured into St. Louis, where the Freedmen's Relief Society, the Ladies Union Aid Society, the Western Sanitary Commission, and the American Missionary Association (AMA) set up schools for their children.[30]

Union states

The Union states were:

|

|

* Border states with slavery in 1861: In Kentucky and Missouri, pro-secession "governments" declared for the South but never had significant control of the states.

West Virginia separated from Virginia and became part of the Union during the war, on June 20, 1863. Nevada also joined the Union during the war, becoming a state on October 31, 1864.

Union Territories

The Union controlled territories in April, 1861 were:

- Colorado Territory

- Dakota Territory

- Indian Territory (disputed with the Confederacy)

- Nebraska Territory

- Nevada Territory (became a state in 1864)

- New Mexico Territory

- Arizona Territory (split off in 1863)

- Utah Territory

- Washington Territory

- Idaho Territory (split off in 1863)

- Montana Territory (split off in 1864)

- Idaho Territory (split off in 1863)

Notes

- ^ "Second Inaugural Address of Abraham Lincoln".

- ^ Kenneth M. Stampp, "The Concept of a Perpetual Union," in The Imperiled Union: Essays on the Background of the Civil War (1980), p. 30

- ^ Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln (2005)

- ^ Phillip Shaw Paludan, The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln (1994) pp 21-48

- ^ Leonard P. Curry, Blueprint for Modern America: Nonmilitary Legislation of the First Civil War Congress (1968)

- ^ Robert Cook, "Stiffening Abe: William Pitt Fessenden and the Role of the Broker Politician in the Civil War Congress," American Nineteenth Century History, June 2007, Vol. 8 Issue 2, pp 145-167

- ^ Bruce Tap, "Inevitability, masculinity, and the American military tradition: the committee on the conduct of the war investigates the American Civil War," American Nineteenth Century History, July 2004, Vol. 5 Issue 2, po 19-46

- ^ Kenneth M. Stampp, Indiana Politics during the Civil War (1949) online edition

- ^ Joel Silbey, A respectable minority: the Democratic Party in the Civil War era, 1860-1868 (1977) online edition

- ^ Lewis J. Wertheim, "The Indianapolis Treason Trials, the Elections of 1864 and the Power of the Partisan Press." Indiana Magazine of History 1989 85(3): 236-250.

- ^ Jennifer L. Weber, Copperheads: The Rise and Fall of Lincoln's Opponents in the North (2006)

- ^ Frank L. Klement, Lincoln's Critics: The Copperheads of the North (1999)

- ^ Barnet Schecter, The Devil's Own Work: The Civil War Draft Riots and the Fight to Reconstruct America (2005)

- ^ The New York City Draft Riots In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863, by Leslie M. Harris

- ^ Kenneth H. Wheeler, "Local autonomy and civil war draft resistance: Holmes County, Ohio," Civil War History, June 1999, Vol. 45 Issue 2, pp 147-58

- ^ Heather Cox Richardson, The Greatest Nation of the Earth: Republican Economic Policies during the Civil War (1997)

- ^ Richardson, 100, 113

- ^ James L. Huston, "A Political Response to Industrialism: The Republican Embrace of Protectionist Labor Doctrines," Journal of American History, June 1983, Vol. 70 Issue 1, pp 35-57 in JSTOR

- ^ Jerry W. Markham, A financial history of the United States (2001) vol 3 p 220

- ^ Paul W. Gates, Agriculture and the Civil War (1965)

- ^ J.L. Anderson, "The Vacant Chair on the Farm: Soldier Husbands, Farm Wives, and the Iowa Home Front, 1861-1865," Annals of Iowa, Summer/Fall 2007, Vol. 66 Issue 3/4, pp 241-265

- ^ Kathleen L. Endres, "A Voice for the Christian Family: The Methodist Episcopal 'Ladies' Repository' in the Civil War," Methodist History, Jan 1995, Vol. 33 Issue 2, p84-97,

- ^ Stephen M. Frank, "'Rendering aid and comfort': Images of fatherhood in the letters of Civil War soldiers from Massachusetts and Michigan," Journal of Social History, Fall 1992, Vol. 26 Issue 1, pp 5-31 in JSTOR

- ^ James Marten, Children for the Union: The War Spirit of the Northern Home Front (2004) p. 17

- ^ James Marten, "For the good, the true, and the beautiful: Northern children's magazines and the Civil War," Civil War History, Mar 1995, Vol. 41 Issue 1, pp 57-75

- ^ James Marten, "History in a Box: Milton Bradley's Myriopticon," Journal of the History of Childhood & Youth, Winter 2009, Vol. 2 Issue 1, pp 5-7

- ^ Marten, Children for the Union pp 107, 166

- ^ George Gallarno, "How Iowa Cared for Orphans of Her Soldiers of the Civil War," Annals of Iowa, Jan 1926, Vol. 15 Issue 3, pp 163-193

- ^ F. Talbott, "Some Legislative and Legal Aspects of the Negro Question in West Virginia during the Civil War and Reconstruction," West Virginia History, Jan 1963, Vol. 24 Issue 2, pp 110-133

- ^ Lawrence O. Christensen, "Black Education in Civil War St. Louis," Missouri Historical Review, April 2001, Vol. 95 Issue 3, pp 302-316

Bibliography

Surveys

- Fellman, Michael et al. This Terrible War: The Civil War and its Aftermath (2nd ed. 2007), 544 page survey

- Ford, Lacy K., ed. A Companion to the Civil War and Reconstruction. (2005). 518 pp. 23 essays by scholars excerpt and text search

- Heidler, David Stephen, ed. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History (2002), 1600 entries in 2700 pages in 5 vol or 1-vol editions; very good basic reference

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (1988), 900 page survey; Pulitzer prize

- Nevins, Allan. Ordeal of the Union, an 8-volume set (1947-1971). the most detailed political, economic and military narrative; by Pulitzer Prize winner

- 1. Fruits of Manifest Destiny, 1847-1852; 2. A House Dividing, 1852-1857; 3. Douglas, Buchanan, and Party Chaos, 1857-1859; 4. Prologue to Civil War, 1859-1861; 5. The Improvised War, 1861-1862; 6. War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863; 7. The Organized War, 1863-1864; 8. The Organized War to Victory, 1864-1865

- Resch, John P. et al., Americans at War: Society, Culture and the Homefront vol 2: 1816-1900 (2005)

Politics

- Donald, David Herbert. Lincoln (1999) the ebest biography; excerpt and text search

- Gienapp. William E. Abraham Lincoln and Civil War America: A Biography (2002), good short online edition

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln (2005) excerpts and text search

- Green, Michael S. Freedom, Union, and Power: Lincoln and His Party during the Civil War. (2004). 400 pp.

- Paludan, Philip S. The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln (1994), thorough treatment of Lincoln's administration

- Richardson, Heather Cox. The Greatest Nation of the Earth: Republican Economic Policies during the Civil War (1997) online edition

- Weber, Jennifer L. Copperheads: The Rise and Fall of Lincoln's Opponents in the North (2006) excerpt and text search

Economics

- Clark, Jr., John E. Railroads in the Civil War: The Impact of Management on Victory and Defeat (2004)

- Weber, Thomas. The northern railroads in the Civil War, 1861-1865 (1999)

- Wilson, Mark R. The Business of Civil War: Military Mobilization and the State, 1861-1865. (2006). 306 pp. excerpt and text search

Race

- McPherson, James M. Marching Toward Freedom: The Negro's Civil War (1982); first edition was The Negro's Civil War: How American Negroes Felt and Acted During the War for the Union (1965),

- Quarles, Benjamin. The Negro in the Civil War (1953), standard history excerpt and text search

Religion

- Miller, Randall M., Harry S. Stout, and Charles Reagan Wilson, eds. Religion and the American Civil War (1998) online edition

- Miller, Robert J. Both Prayed to the Same God: Religion and Faith in the American Civil War. (2007). 260pp

- Noll, Mark A. The Civil War as a Theological Crisis. (2006). 199 pp.

- Stout, Harry S. Upon the Altar of the Nation: A Moral History of the Civil War. (2006). 544 pp.

Soldiers

- Cimbala, Paul A., and Randall M. Miller, eds. Union Soldiers and the Northern Home Front: Wartime Experiences, Postwar Adjustments. (2002)

- Current, Richard N. (1994). Lincoln's Loyalists: Union Soldiers from the Confederacy. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508465-9.

- McPherson, James. For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War (1998), based on letters and diaries

State and local

- Bak, Richard. A Distant Thunder: Michigan in the Civil War. Chelsea: Huron River, 2004. 239 pp.

- Gallman, Matthew J. (1990) Mastering Wartime: A Social History of Philadelphia During the Civil War. New York: Cambridge University Press

- Pierce, Bessie. A History of Chicago (1943) vol 2

Women and family

- Anderson, J. L. "The Vacant Chair on the Farm: Soldier Husbands, Farm Wives, and the Iowa Home Front, 1861-1865," Annals of Iowa (2007) 66: 241-265

- Attie, Jeanie. Patriotic Toil: Northern Women and the American Civil War (1998). 294 pp.

- Bahde, Thomas. "'I never wood git tired of wrighting to you.'" Journal of Illinois History (2009). 12:129-55

- Giesberg, Judith. Army at Home: Women and the Civil War on the Northern Home Front (2009) excerpt and text search

- Giesberg, Judith Ann. "From Harvest Field to Battlefield: Rural Pennsylvania Women and the U.S. Civil War," Pennsylvania History (2005). 72: 159-191

- Harper, Judith E. Women during the Civil War: An Encyclopedia. (2004). 472 pp.

- Marten, James. Children for the Union: The War Spirit on the Northern Home Front. Ivan R. Dee, 2004. 209 pp.

- Massey, Mary. Bonnet Brigades: American Women and the Civil War (1966), excellent overview North and South; reissued as Women in the Civil War (1994)

- Scott, Sean A. "'Earth Has No Sorrow That Heaven Cannot Cure': Northern Civilian Perspectives on Death and Eternity during the Civil War," Journal of Social History (2008) 41:843-866

- Silber, Nina. Daughters of the Union: Northern Women Fight the Civil War. Harvard U. Press, 2005. 332 pp.

- Venet, Wendy Hamand. A Strong-Minded Woman: The Life of Mary Livermore. U. of Massachusetts Press, 2005. 322 pp.

Primary sources

- American Annual Cyclopaedia for 1861 (N.Y.: Appleton's, 1864), an extensive collection of reports on each state, Congress, and military activities, and many other topics; annual issues from 1861 to 1901 in major libraries

- Angle, Paul M. , and Earl Schenck Miers, eds. Tragic Years, 1860-1865: A Documentary History of the American Civil War - Vol. 1 1960 online edition

- Carter, Susan B., ed. The Historical Statistics of the United States: Millennial Edition (5 vols), 2006; online at many universities

- Commager, Henry Steele, ed. The Blue and the Gray. The Story of the Civil War as Told by Participants. (1950), excerpts from primary sources

- Dee, Christine, ed. Ohio's War: The Civil War in Documents. (2007). 244 pp.

- Hesseltine, William B. ed.; The Tragic Conflict: The Civil War and Reconstruction (1962), excerpts from primary sources online edition

- Marten, James, ed.. Civil War America: Voices from the Home Front. (2003). 346 pp.

- Risley, Ford, ed. The Civil War: Primary Documents on Events from 1860 to 1865. (2004). 320 pp.

- Sizer, Lyde Cullen and Jim Cullen, ed. The Civil War Era: An Anthology of Sources. (2005). 434 pp.

- diaries, journals. reminiscences