History of the United States (1945–1964): Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 204.183.117.130 (talk) to last version by 84.119.84.14 |

→Korean War: add McCarthyism |

||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

After a few weeks of retreat, General [[Douglas MacArthur]]'s success at the [[Battle of Inchon]] turned the war around; UN forces invaded North Korea. This advantage was lost when hundreds of thousands of Chinese entered an undeclared war against the United States and pushed the US/UN/Korean forces back to the original starting line, the 38th parallel. The war became a stalemate, with over 33,000 American dead and 100,000 wounded [http://siadapp.dior.whs.mil/personnel/CASUALTY/korea.pdf#search=%22deaths%20korean%20war%22] but nothing to show for it except a resolve to continue the containment policy. Truman fired MacArthur but was unable to end the war. [[Dwight D. Eisenhower]] in 1952 campaigned against Truman's failures of "Korea, Communism and Corruption," promising to go to Korea himself and end the war. By threatening to use nuclear weapons in 1953, Eisenhower ended the war with a truce that is still in effect.<ref>Spencer Tucker, ed. ''The Encyclopedia of the Korean War'' (3 vol 2010)</ref> |

After a few weeks of retreat, General [[Douglas MacArthur]]'s success at the [[Battle of Inchon]] turned the war around; UN forces invaded North Korea. This advantage was lost when hundreds of thousands of Chinese entered an undeclared war against the United States and pushed the US/UN/Korean forces back to the original starting line, the 38th parallel. The war became a stalemate, with over 33,000 American dead and 100,000 wounded [http://siadapp.dior.whs.mil/personnel/CASUALTY/korea.pdf#search=%22deaths%20korean%20war%22] but nothing to show for it except a resolve to continue the containment policy. Truman fired MacArthur but was unable to end the war. [[Dwight D. Eisenhower]] in 1952 campaigned against Truman's failures of "Korea, Communism and Corruption," promising to go to Korea himself and end the war. By threatening to use nuclear weapons in 1953, Eisenhower ended the war with a truce that is still in effect.<ref>Spencer Tucker, ed. ''The Encyclopedia of the Korean War'' (3 vol 2010)</ref> |

||

===Anti-Communism and McCarthyism: 1947-54=== |

|||

{{main|McCarthyism}} |

|||

In 1947, well before McCarthy became active, the [[Conservative Coalition]] in Congress passed the [[Taft Hartley Act]], designed to balance the rights of management and unions, and delegitimizing Communist union leaders. The challenge of rooting out Communists from labor unions and the Democratic party was successfully undertaken by liberals, such as [[Walter Reuther]] of the autoworkers union<ref>Martin Halpern, "Taft-Hartley and the Defeat of the Progressive Alternative in the United Auto Workers," ''Labor History,'' Spring 1986, Vol. 27 Issue 2, pp 204-26</ref> and [[Ronald Reagan]] of the Screen Actors Guild (Reagan was a liberal Democrat at the time).<ref>Lou Cannon, ''President Reagan: the role of a lifetime'' (2000) p. 245</ref> Many of the purged leftists joined the presidential campaign in 1948 of FDR's Vice President [[Henry A. Wallace]]. |

|||

[[File:Is this tomorrow.jpg|thumb|225px|A 1947 booklet published by the Catholic Catechetical Guild Educational Society raising the specter of a Communist takeover]] |

|||

The [[House Un-American Activities Committee]], with young Congressman [[Richard M. Nixon]] playing a central role, accused [[Alger Hiss]], a top Roosevelt aide, of being a Communist spy, using testimony and documents provided by [[Whittaker Chambers]]. Hiss was convicted and sent to prison, with the anti-Communists gaining a powerful political weapon.<ref>Sam Tanenhaus, ''Whittaker Chambers: a biography'' (1988) </ref> It launched Nixon's meteoric rise to the Senate (1950) and the vice presidenncy (1952).<ref>Roger Morris, ''Richard Milhous Nixon: The Rise of an American Politician'' (1991) </ref> |

|||

When anxiety over Communism in Korea and China reached fever pitched in 1950, a previously obscure Senator, [[Joe McCarthy]] of Wisconsin, launched extremely high visibility investigations into the cover-up of spies in the government. McCarthy used careless tactics that allowed his opponents to effectively counterattack. Irish Catholics (including Buckley and the [[Kennedy Family]]) were intensely anti-Communist and defended McCarthy (a fellow Irish Catholic).<ref> William F. Buckley and L. Brent Bozell, ''Mccarthy and His Enemies: The Record and Its Meaning'' (1954)</ref> Paterfamilias [[Joseph Kennedy]] (1888–1969), a very active conservative Democrat, was McCarthy's most ardent supporter and got his son [[Robert F. Kennedy]] a job with McCarthy. McCarthy had talked of "twenty years of treason" (i.e. since Roosevelt's election in 1932). When he in 1953 he started talking of "21 years of treason and launched a major attack on the Army for promoting a Communist dentist in the medical corps, his recklessness was too much for Eisenhower, who encouraged Republicans to censure McCarthy formally in 1954. The Senator's power collapsed overnight. Senator [[John F. Kennedy]] did not vote for censure.<ref>Richard M. Fried, ''Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective'' (1990)</ref> |

|||

McCarthy and McCarthyism was always of far more importance to liberals than conservatives. He became a liberal target, and made liberals look like the innocent victims. "McCarthyism" was expanded to include attacks on supposed Communist influence in Hollywood, which resulted in a black-list whereby artists who refused to testify about possible Communist connections could not get work. Some famous celebrities (such as [[Charlie Chaplin]]) left the U.S.; other worked under pseudonyms (such as [[Dalton Trumbo]]). McCarthyism included investigations into academics and teachers as well.<ref> Ellen Schrecker, ''The Age of McCarthyism: A Brief History with Documents'' (2d ed. 2002)</ref> |

|||

===Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations=== |

===Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations=== |

||

Revision as of 09:32, 30 May 2011

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of the United States |

|---|

|

For the United States, 1945 to 1964 was an era of economic growth and prosperity which saw the victorious powers of World War II confronting each other in the Cold War and the triumph of the Civil Rights Movement that ended Jim Crow segregation in the South.[1]

The period saw an active foreign policy designed to rescue Europe and Asia from the devastation of World War II and to contain the expansion of Communism, represented by the Soviet Union and China. A race began to overawe the other side with more powerful nuclear weapons. The Soviets formed the Warsaw Pact of communist states to oppose the American-led North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance. The U.S. fought a bloody, inconclusive war in Korea and was escalating the war in Vietnam as the period ended.[2]

On the domestic front, after a short transition, the economy grew rapidly, with widespread prosperity, rising wages, and the movement of most of the remaining farmers to the towns and cities. Politically, the era was dominated by presidents, Democrats Harry Truman (1945–53), John F. Kennedy (1961–63) and Lyndon Johnson (1963–69), and Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower (1953–61). For most of the period, the Democrats controlled Congress; however, they were usually unable to pass liberal legislation because of the power of the Conservative Coalition. The Liberal coalition came to power after Kennedy's assassination in 1963, and launched the Great Society.[3]

Cold War

Origins

When the war ended in Europe on May 8, 1945, Soviet and Western (U.S., British, and French) troops were located along a line through the center of Germany. Aside from a few minor adjustments, this would be the "Iron Curtain" of the Cold War. As agreed at the Potsdam Conference, the Germans living east of the Oder-Neisse Line were expelled. In hindsight, the Yalta Conference signified the agreement of both sides that they could stay there and that neither side would use direct force to push the other out. This tacit accord applied to Asia as well, as evidenced by U.S. occupation of Japan and the division of Korea. With the onset of the Cold War, a brief postwar status quo emerged until the Communist takeover in China in 1949. Communist hegemony reigned over about one third of the world's territory while the United States emerged as the world's more influential superpower with respect to the other two thirds[4]

There were fundamental contrasts between the visions of the United States and the Soviet Union, between capitalism with liberal democracy and totalitarian communism. The United States, led by President Harry S. Truman since April 1945, had planned to use the new United Nations to resolve troubles, but it failed in that purpose.[5] The U.S. rejected totalitarianism and colonialism, in line with the principles laid down by the Atlantic Charter of 1941: self-determination, equal economic access, and a rebuilt capitalist, democratic Europe that could again serve as a hub in world affairs.

The only major industrial power in the world whose economy emerged intact—and even greatly strengthened—was the United States. Although President Franklin D. Roosevelt thought his personal relationship with Joseph Stalin could dissolve future difficulties, President Truman was much more skeptical.

The Soviets, too, saw their vital interests in the containment or roll-back of capitalism near their borders. Joseph Stalin was determined to absorb the Baltics, neutralize Finland and Austria, and set up pro-Moscow regimes in Poland, Romania, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, East Germany, and Bulgaria. He at first collaborated with Tito in Yugoslavia, but then they became enemies., Stalin ignored his promises at Yalta (Feb. 1945) when he had promised that "free elections" would go ahead in Eastern Europe. Former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in 1946 condemned Stalin for cordoning off a new Russian empire with an "iron curtain".[6]

Containment and escalation

In the United States, containment of the Soviet Union soon became foreign policy doctrine, following the advice of State Department officer George Kennan, who argued that the USSR had to be "contained" using "unalterable counterforce at every point," until the internal breakdown of Soviet power occurred. This policy was further articulated in the Truman Doctrine Speech to Congress of March 1947, which argued that the United States would have to contribute US$4 billion to efforts to "contain" communism. This came amid the crisis of the Greek Civil War (1946–1949), with a Communist-led civil war, and Soviet threats to in Turkey and Iran. Truman warned that if Greece and Turkey did not receive the aid that they needed, they would inevitably fall to Communism. Truman won over both his own Democratic Party in Congress, and most Republicans as well. Senator Arthur Vandenberg led the GOP internationalists and overcame the opposition of Senator Robert A. Taft and the isolationists. Truman signed the Truman Doctrine into law in May 1947, which granted $400 million in military and economic aid to Turkey and Greece.

Germany, badly tattered by the war, and unable to deal with an influx of millions of refugees, needed special help. In view of the deteriorating economic and political situation in Europe[7], in 1948 the United States initiated a new economic reconstruction effort, first in Western Europe and then in Japan (as well as in South Korea and Taiwan) known as the Marshall Plan, allocating $12 billion to economic reconstruction, infrastructure, and modernization of industry. Stalin vetoed any participation by his satellites and responded by blocking access to Berlin, which was deep within the Soviet zone of Germany. The United States and Britain dramatically supported the people of West Berlin and flew supplies into Berlin through the Berlin Airlift in 1948-49. The lifting of the blockade in 1949 marked a propaganda defeat for the Soviets against the efforts of Great Britain and the U.S.

Under the leadership of Secretary of State Dean Acheson, the U.S. organized eleven other nations in 1949 to form the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), America's first "entangling" military alliance in 170 years. Stalin retaliated by integrating the economies of Eastern Europe in his version of the Marshall Plan, exploding the first Soviet atomic device in 1949, signing an alliance with the People's Republic of China in February 1950, and forming the Warsaw Pact, his counterpart to NATO in 1955.

In 1949, the communist leader Mao Zedong won control of mainland China, proclaimed the People's Republic of China, then traveled to Moscow where he negotiated the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship.

Confronted with growing Communist successes, the Truman administration in a secret war plan, NSC-68, set out to strengthen their alliance systems, and quadruple defense spendingTruman ordered the development of the Hydrogen bomb; similar Soviet nuclear development followed thereafter.

In the early 1950s, the U.S. drew plans to form a West German army, and proposals were made for a peace treaty with Japan that would guarantee long-term U.S. military bases for forward deployment of U.S. armed forces in East Asia.

The Truman Doctrine also contributed to America's first involvement in Vietnam. The U.S. financed France's bid to hold onto its Indo-Chinese colonies, on the proviso that the Vietnamese be given more authority. The United States supplied French forces with equipment and military advisers in order to combat the communist Vietnamese independence movement Viet Minh in the First Indochina War. In 1954 the U.S. started actively supporting the government in the South, and Diem, with this support, refused to enter into reunification talks and declared himself as president. [1]

The U.S. involvement in Laos was kept secret from the public, but through the CIA activities in Laos the U.S. supported the Laotian government in the war against the Pathet Lao. However, by 1960, the Laotian government was "reeling with corruption" as a result of all the U.S. funds flowing to it.[citation needed]

Korean War

Stalin approved a North Korean plan to invade U.S.-supported South Korea in June 1950. President Truman immediately committed U.S. forces to Korea. He did not consult or gain approval of Congress but did gain the approval of the United Nations (UN) to drive back the North Koreans and re-unite that country in terms of a rollback strategy[8]

After a few weeks of retreat, General Douglas MacArthur's success at the Battle of Inchon turned the war around; UN forces invaded North Korea. This advantage was lost when hundreds of thousands of Chinese entered an undeclared war against the United States and pushed the US/UN/Korean forces back to the original starting line, the 38th parallel. The war became a stalemate, with over 33,000 American dead and 100,000 wounded [2] but nothing to show for it except a resolve to continue the containment policy. Truman fired MacArthur but was unable to end the war. Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952 campaigned against Truman's failures of "Korea, Communism and Corruption," promising to go to Korea himself and end the war. By threatening to use nuclear weapons in 1953, Eisenhower ended the war with a truce that is still in effect.[9]

Anti-Communism and McCarthyism: 1947-54

In 1947, well before McCarthy became active, the Conservative Coalition in Congress passed the Taft Hartley Act, designed to balance the rights of management and unions, and delegitimizing Communist union leaders. The challenge of rooting out Communists from labor unions and the Democratic party was successfully undertaken by liberals, such as Walter Reuther of the autoworkers union[10] and Ronald Reagan of the Screen Actors Guild (Reagan was a liberal Democrat at the time).[11] Many of the purged leftists joined the presidential campaign in 1948 of FDR's Vice President Henry A. Wallace.

The House Un-American Activities Committee, with young Congressman Richard M. Nixon playing a central role, accused Alger Hiss, a top Roosevelt aide, of being a Communist spy, using testimony and documents provided by Whittaker Chambers. Hiss was convicted and sent to prison, with the anti-Communists gaining a powerful political weapon.[12] It launched Nixon's meteoric rise to the Senate (1950) and the vice presidenncy (1952).[13]

When anxiety over Communism in Korea and China reached fever pitched in 1950, a previously obscure Senator, Joe McCarthy of Wisconsin, launched extremely high visibility investigations into the cover-up of spies in the government. McCarthy used careless tactics that allowed his opponents to effectively counterattack. Irish Catholics (including Buckley and the Kennedy Family) were intensely anti-Communist and defended McCarthy (a fellow Irish Catholic).[14] Paterfamilias Joseph Kennedy (1888–1969), a very active conservative Democrat, was McCarthy's most ardent supporter and got his son Robert F. Kennedy a job with McCarthy. McCarthy had talked of "twenty years of treason" (i.e. since Roosevelt's election in 1932). When he in 1953 he started talking of "21 years of treason and launched a major attack on the Army for promoting a Communist dentist in the medical corps, his recklessness was too much for Eisenhower, who encouraged Republicans to censure McCarthy formally in 1954. The Senator's power collapsed overnight. Senator John F. Kennedy did not vote for censure.[15]

McCarthy and McCarthyism was always of far more importance to liberals than conservatives. He became a liberal target, and made liberals look like the innocent victims. "McCarthyism" was expanded to include attacks on supposed Communist influence in Hollywood, which resulted in a black-list whereby artists who refused to testify about possible Communist connections could not get work. Some famous celebrities (such as Charlie Chaplin) left the U.S.; other worked under pseudonyms (such as Dalton Trumbo). McCarthyism included investigations into academics and teachers as well.[16]

Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations

In 1953, Stalin died, and after new 1952 presidential election, President Dwight D. Eisenhower used the opportunity to end the Korean War, while continuing Cold War policies. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles was the dominant figure in the nation's foreign policy in the 1950s. Dulles denounced the "containment" of the Truman administration and espoused an active program of "liberation", which would lead to a "rollback" of communism. The most prominent of those doctrines was the policy of "massive retaliation", which Dulles announced early in 1954, eschewing the costly, conventional ground forces characteristic of the Truman administration in favor of wielding the vast superiority of the U.S. nuclear arsenal and covert intelligence. Dulles defined this approach as "brinkmanship".[17]

A dramatic and unexpected shock to Americans' self-confidence and its technological superiority came in 1957, when the Soviets beat the United States into outer space by launching Sputnik, the first earth satellite. The space race began, and by the early 1960s the United States had forged ahead, with President Kennedy promising to land a man on the moon by the end of the 1960s—the landing indeed took place on July 20, 1969.[18]

Trouble close to home appeared when the Soviets formed an alliance with Cuba after Fidel Castro's successful revolution in 1959.

East Germany was the weak point in the Soviet empire, with refugees leaving for the West by the thousands every week. The Soviet solution came in 1961, with the Berlin Wall to stop East Germans from fleeing communism. This was a major propaganda setback for the USSR, but it did allow them to keep control of East Berlin.[19]

The Communist world split in half, as China turned against the Soviet Union; Mao denounced Khrushchev for going soft on capitalism. However, the US failed to take advantage of this split until President Richard Nixon saw the opportunity in 1969. In 1958, the U.S. sent troops into Lebanon for nine months to stabilize a country on the verge of civil war. Between 1954 and 1961, Eisenhower dispatched large sums of economic and military aid and 695 military advisers to South Vietnam to stabilize the pro-western government under attack by insurgents. Eisenhower supported CIA efforts to undermine anti-American governments, which proved most successful in Iran and Guatemala.[20]

The first major strain among the NATO alliance occurred in 1956 when Eisenhower forced Britain and France to retreat from their invasion of Egypt (with Israel) which was intended to get back their ownership of the Suez Canal. Instead of supporting the claims of its NATO partners, the Eisenhower administration stated that it opposed French and British imperial adventurism in the region by sheer prudence, fearing that Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser's standoff with the region's old colonial powers would bolster Soviet power in the region.[21]

The Cold War reached its most dangerous point during the Kennedy administration in the Cuban Missile Crisis, a tense confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States over the Soviet deployment of nuclear missiles in Cuba. The crisis began on October 16, 1962, and lasted for thirteen days. It was the moment when the Cold War was closest to exploding into a devastating nuclear exchange between the two superpower nations. Kennedy decided not to invade or bomb Cuba but to institute a naval blockade of the island. The crisis ended in a compromise, with the Soviets removing their missiles publicly, and the United States secretly removing its nuclear missiles in Turkey. In Moscow, Communist leaders removed Nikita Khrushchev because of his reckless behavior.[22]

"Affluent Society" and the "Other America"

The immediate years unfolding after World War II were generally ones of stability and prosperity for Americans. The nation reconverted its war machine back into a consumer culture overnight. The growth of consumerism, the suburbs, and the economy, however, overshadowed the fact that prosperity did not extend to everyone. Many Americans continued to live in poverty throughout the Eisenhower years, especially older people and racial minorities. Increasing numbers enjoyed high wages, larger houses, better schools, more cars and home comforts like vacuum cleaners, washing machines—which were all made for labor-saving and to make housework easier. Inventions familiar in the early 21st century made their first appearance during this era. The live-in maid and cook, common features of middle-class homes at the beginning of the century, were virtually unheard of in the 1950s; only the very rich had servants. Householders enjoyed centrally heated homes with running hot water. New style furniture was bright, cheap, and light, and easy to move around.[23] Between 1946 and 1960, the United States witnessed a significant expansion in the consumption of goods and services. GNP rose by 36% and personal consumption expenditures by 42%, cumulative gains which were reflected in the incomes of families and unrelated individuals. While the number of these units rose sharply from 43.3 million to 56.1 million in 1960, a rise of almost 23%, their average incomes grew even faster, from $3940 in 1946 to $6900 in 1960, an increase of 43%. After taking inflation into account, the real advance was 16%. The dramatic rise in the average American standard of living was such that, according to George Katona,

“Today in this country minimum standards of nutrition, housing and clothing are assured, not for all, but for the majority. Beyond these minimum needs, such former luxuries as homeownership, durable goods, travel, recreation, and entertainment are no longer restricted to a few. The broad masses participate in enjoying all these things and generate most of the demand for them.”[24]

More than 21 million housing units were constructed between 1946 and 1960, and in the latter year 52% of consumer units in the metropolitan areas owned their own homes. In 1957, out of all the wired homes throughout the country, 96% had a refrigerator, 87% an electric washer, 81% a television, 67% a vacuum cleaner, 18% a freezer, 12% an electric or gas dryer, and 8% air conditioning. Car ownership also soared, with 72% of consumer units owning an automobile by 1960.[24]

The period from 1946 to 1960 also witnessed a significant increase in the paid leisure time of working people. The forty-hour workweek established by the Fair Labor Standards Act in covered industries became the actual schedule in most workplaces by 1960, while uncovered workers such as farmworkers and the self-employed worked less hours than they had done previously, although they still worked much longer hours than most other workers. Paid vacations also became to be enjoyed by the vast majority of workers, with 91% of blue-collar workers covered by major collective bargaining agreements receiving paid vacations by 1957 (usually to a maximum of three weeks), while by the early Sixties virtually all industries paid for holidays and most did so for seven days a year. Industries catering to leisure activities blossomed as a result of most Americans enjoying significant paid leisure time by 1960,[24] while average blue-collar and white-collar workers had come to expect to hold on to their jobs for life.[25]

In regards to social welfare, the postwar era saw a considerable improvement in insurance for workers and their dependants against the risks of death, illness, and old age. With the exception of farm and domestic workers, virtually all members of the labor force were covered by a public old-age pension scheme, and a Bureau of Labor Statistics survey of 188 metropolitan Areas in 1959-60 found that about two-thirds of the plant workers and three-fourths of the office workers were provided with supplemental private pension plans. The study conducted by the BLS also found that 86% of plant workers and 83% of office workers were eligible for hospital insurance while the figures for medical care were 59% for plant workers and 61% for office workers. Life insurance was also available to 89% of plant employees and 92% of office workers.[24]

At the center of middle-class culture in the 1950s was a growing demand for consumer goods; a result of the postwar prosperity, the increase in variety and availability of consumer products, and advertising. Affluent Americans in the 1950s and 1960s responded to consumer demand for automobiles, dishwashers, garbage disposals, black and white television sets, and stereo phonographs. To a striking degree, the prosperity of the 1950s and 1960s was consumer-driven (as opposed to investment-driven).

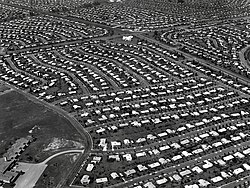

As the population of suburbia, with its increased mobility, swelled to account for a third of the nation's population by 1960, U.S. auto manufacturers in Detroit built more automobiles. The growth of suburbs was not only a result of postwar prosperity, but innovations of the single-family housing market. William Levitt began a national trend with his use of mass-production techniques to construct a large "Levittown" housing development on Long Island. Meanwhile, the suburban population swelled because of the baby boom. Suburbs provided larger homes for larger families, security from urban living, privacy, and space for consumer goods.[26]

Civil Rights Movement

Following the end of Reconstruction, many states adopted restrictive Jim Crow laws which enforced segregation of the races and the second-class status of African Americans. The Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson 1896 accepted segregation as constitutional. Voting rights discrimination remained widespread in the South through the 1950s. Fewer than 10% voted in the Deep South, although a larger proportion voted in the border states, and the blacks were being organized into Democratic machines in the northern cities. Although both parties pledged progress in 1948, the only major development before 1954 was the integration military.[27]

Brown v. Board of Education and "massive resistance"

In the early days of the civil rights movement, litigation and lobbying were the focus of integration efforts. The U.S. Supreme Court decisions in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954); Powell v. Alabama (1932); Smith v. Allwright (1944); Shelley v. Kraemer (1948); Sweatt v. Painter (1950); and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Board of Regents (1950) led to a shift in tactics, and from 1955 to 1965, "direct action" was the strategy—primarily bus boycotts, sit-ins, freedom rides, and social movements.

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was a landmark case of the United States Supreme Court which explicitly outlawed segregated public education facilities for blacks and whites, ruling so on the grounds that the doctrine of "separate but equal" public education could never truly provide black Americans with facilities of the same standards available to white Americans. One hundred and one members of the United States House of Representatives and 19 Senators signed "The Southern Manifesto" condemning the Supreme Court decision as unconstitutional.

Governor Orval Eugene Faubus of Arkansas used the Arkansas National Guard to prevent school integration at Little Rock Central High School in 1957. President Eisenhower nationalized state forces and sent in the US Army to enforce federal court orders. Governors Ross Barnett of Mississippi and George Wallace of Alabama physically blocked school doorways at their respective states' universities. Birmingham's public safety commissioner Eugene T. "Bull" Connor advocated violence against freedom riders and ordered fire hoses and police dogs turned on demonstrators. Sheriff Jim Clark of Dallas County, Alabama, loosed his deputies on "Bloody Sunday" marchers and personally menaced other protesters. Police all across the South arrested civil rights activists on trumped-up charges.

Civil rights organizations

Although they had white supporters and sympathizers, the modern civil rights movement was designed, led, organized, and manned by African Americans, who placed themselves and their families on the front lines in the struggle for freedom. Their heroism was brought home to every American through newspaper, and later, television reports as their peaceful marches and demonstrations were violently attacked by law enforcement. Officers used batons, bullwhips, fire hoses, police dogs, and mass arrests to intimidate the protesters. The second characteristic of the movement is that it was not monolithic, led by one or two men. Rather it was a dispersed, grass-roots campaign that attacked segregation in many different places using many different tactics. While some groups and individuals within the civil rights movement—such as Malcolm X—advocated Black Power, black separatism, or even armed resistance, the majority of participants remained committed to the principles of nonviolence, a deliberate decision by an oppressed minority to abstain from violence for political gain. Using nonviolent strategies, civil rights activists took advantage of emerging national network-news reporting, especially television, to capture national attention.[28]

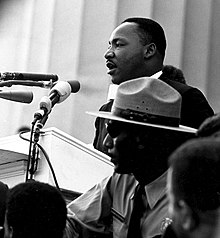

The leadership role of black churches in the movement was a natural extension of their structure and function. They offered members an opportunity to exercise roles denied them in society. Throughout history, the black church served as a place of worship and also as a base for powerful ministers, such as Congressman Adam Clayton Powell in New York City. The most prominent clergyman in the civil rights movement was Martin Luther King, Jr. Time magazine's 1963 "Man of the Year" showed tireless personal commitment to black freedom and his strong leadership won him worldwide acclaim and the Nobel Peace Prize.

Students and seminarians in both the South and the North played key roles in every phase of the civil rights movement. Church and student-led movements developed their own organizational and sustaining structures. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), founded in 1957, coordinated and raised funds, mostly from northern sources, for local protests and for the training of black leaders. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, founded in 1957, developed the "jail-no-bail" strategy. SNCC's role was to develop and link sit-in campaigns and to help organize freedom rides, voter registration drives, and other protest activities. These three new groups often joined forces with existing organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), founded in 1942, and the National Urban League. The NAACP and its Director, Roy Wilkins, provided legal counsel for jailed demonstrators, helped raise bail, and continued to test segregation and discrimination in the courts as it had been doing for half a century. CORE initiated the 1961 Freedom Rides which involved many SNCC members, and CORE's leader James Farmer later became executive secretary of SNCC.

The administration of President John F. Kennedy supported enforcement of desegregation in schools and public facilities. Attorney General Robert Kennedy brought more than 50 lawsuits in four states to secure black Americans' right to vote. However, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, concerned about possible communist influence in the civil rights movement and personally antagonistic to King, used the FBI to discredit King and other civil rights leaders.[29]

Presidential administrations

Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956

Eisenhower was elected in 1952 as a Republican and former general. His administrations are sometimes thought to be benign, but his eight years in office were marked by three recessions and continued covert action against foreign governments. "Ike" was popular and had an engaging smile, and his administration was also marked by the first televised press conferences by a president. His farewell address to the nation surprised many of his former military friends by famously warning of the dangers of a growing "military industrial complex."[30]

Kennedy in 1960

The very close 1960 election pitted Republican Vice President Richard Nixon against the Democrat John F. Kennedy. Historians have explained Kennedy's victory in terms of an economic recession, the numerical dominance of 17 million more registered Democrats than Republicans, the votes that Kennedy gained among Catholics practically matched the votes Nixon gained among Protestants,[31] Kennedy's better organization, and Kennedy's superior campaigning skills. Nixon's emphasis on his experience carried little weight, and he wasted energy by campaigning in all 50 states instead of concentrating on the swing states. Kennedy used his large, well-funded campaign organization to win the nomination, secure endorsements, and with the aid of the last of the big-city bosses to get out the vote in the big cities. He relied on Johnson to hold the South and used television effectively.[32][33] Kennedy was the first Catholic to run for president since Al Smith's ill-fated campaign in 1928. Voters were polarized on religious grounds, but Kennedy's election was a transforming event for Catholics, who finally realized they were accepted in a America, and it marked the virtual end of anti-Catholicism as a political force.[34]

The Kennedy Family had long been leaders of the Irish Catholic wing of the Democratic Party; JFK was middle-of-the-road or liberal on domestic issues and conservative on foreign policy, sending military forces into Cuba and Vietnam. The Kennedy style called for youth, dynamism, vigor and an intellectual approach to aggressive new policies in foreign affairs. The downside was his inexperience in foreign affairs, standing in stark contrast to the vast experience of the president he replaced. He is best known for his call to civic virtue: "And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you - ask what you can do for your country." In Congress the Conservative Coalition blocked nearly all of Kennedy's domestic programs, so there were few changes in domestic policy, even as the civil rights movement gained momentum.[35]

President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963 by Lee Harvey Oswald. The even proved to be one of the greatest psychological shocks to the American people in the 20th century and lead to Kennedy being revered as a martyr and hero.

Johnson, 1963-69

After Kennedy's assassination, vice president Lyndon Baines Johnson served out the remainder of the term, using appeals to finish the job that Kennedy had started to pass a remarkable package of liberal legislation that he called the Great Society Johnson used the full powers of the presidency to ensure passage the Civil Rights Act of 1964. These actions helped Johnson to win a historic landslide in the 1964 presidential election over conservative champion Senator Barry Goldwater. Johnson's big victory brought an overwhelming liberal majority in Congress.[36]

See also

References

- ^ James T. Patterson, Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974 (1988) pp 771-90

- ^ Alan P. Dobson and Steve Marsh, US foreign policy since 1945 (2006) pp 18-29, 76-90

- ^ Alonzo L. Hamby, Liberalism and Its Challengers: From F.D.R. to Bush (2nd ed. 1992) pp 52-139

- ^ John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War: A New History (2006) pp 259-66

- ^ Townsend Hoopes and Douglas Brinkley, FDR and the Creation of the U.N. (2000) pp 205-22

- ^ V. M. Zubok, A Failed Empire: The Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev (2008) pp 29-61

- ^ See Time

- ^ The Soviets were boycotting the UN at that time (because it would not admit the People's Republic of China) and so was not present to veto Truman's actions.

- ^ Spencer Tucker, ed. The Encyclopedia of the Korean War (3 vol 2010)

- ^ Martin Halpern, "Taft-Hartley and the Defeat of the Progressive Alternative in the United Auto Workers," Labor History, Spring 1986, Vol. 27 Issue 2, pp 204-26

- ^ Lou Cannon, President Reagan: the role of a lifetime (2000) p. 245

- ^ Sam Tanenhaus, Whittaker Chambers: a biography (1988)

- ^ Roger Morris, Richard Milhous Nixon: The Rise of an American Politician (1991)

- ^ William F. Buckley and L. Brent Bozell, Mccarthy and His Enemies: The Record and Its Meaning (1954)

- ^ Richard M. Fried, Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective (1990)

- ^ Ellen Schrecker, The Age of McCarthyism: A Brief History with Documents (2d ed. 2002)

- ^ Chester J. Pach and Elmo Richardson, Presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower (1991)

- ^ Paul Dickson, Sputnik: the shock of the century (2003)

- ^ Frederick Taylor, The Berlin Wall: A World Divided, 1961-1989 (2008)

- ^ Stephen E. Ambrose, Ike's spies: Eisenhower and the espionage establishment (1999)

- ^ Cole Christian Kingseed, Eisenhower and the Suez Crisis of 1956 (1995)

- ^ Don Munton and David A. Welch, The Cuban Missile Crisis: A Concise History (2006)

- ^ William H. Young, The 1950s (American Popular Culture Through History) (2004)

- ^ a b c d Promises Kept: John F.Kennedy's New Frontier by Irving Bernstein

- ^ A companion to 20th-century America by Stephen J. Whitfield

- ^ Robert Fishman, Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia (1989)

- ^ Harvard Sitkoff, The Struggle for Black Equality (2008)

- ^ Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954–1963 (1988)

- ^ James Giglio, The Presidency of John F. Kennedy (1991),

- ^ http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=old&doc=90

- ^ Shaun A. Casey, The Making of a Catholic President: Kennedy vs. Nixon, 1960 (2009)

- ^ Hal Brands, "Burying Theodore White: Recent Accounts of the 1960 Presidential Election," Presidential Studies Quarterly 2010. Vol. 40#2 pp 364+.

- ^ W. J. Rorabaugh, The Real Making of the President: Kennedy, Nixon, and the 1960 Election (2009)

- ^ Lawrence H. Fuchs, John F. Kennedy and American Catholicism (1967)

- ^ James Giglio, The Presidency of John F. Kennedy (1991)

- ^ Randall Woods, LBJ: Architect of American Ambition (2006).

Further reading

- Alexander, Charles C. (1975). Holding the Line: The Eisenhower Era, 1952-1961. online edition

- Ambrose, Stephen E. (2003). Eisenhower: The President; also Eisenhower: Soldier and President. Standard scholarly biography

- Beisner, Robert L. (2006). Dean Acheson: A Life in the Cold War. A standard scholarly biography; covers 1945-53 only

- Billington, Monroe (1973). "Civil Rights, President Truman and the South". Journal of Negro History. 58 (2): 127–139. doi:10.2307/2716825.

- Branch, Taylor (1988). Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954–1963. ISBN 0671460978.

- Dallek, Robert (2008). Harry Truman. Short, popular biography by scholar.

- Damms, Richard V. (2002). The Eisenhower Presidency, 1953-1961. 161 pp. short survey by British scholar

- Divine, Robert A. (1981). Eisenhower and the Cold War. online edition

- Fried, Richard M. (1990). Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. online complete edition

- Giglio, James (1991). The Presidency of John F. Kennedy. Standard scholarly overview of policies

- Hamby, Alonzo L. (1995). Man of the People: A Life of Harry S. Truman. Scholarly biography

- Hamby, Alonzo L. (1970). "The Liberals, Truman, and the FDR as Symbol and Myth". Journal of American History. 56 (4): 859–867. doi:10.2307/1917522.

- Hamby, Alonzo (1992). Liberalism and Its Challengers: From F.D.R. to Bush.

- Lacey, Michael J., ed. (1989). The Truman Presidency. Major essays by scholars

- Marwick, Arthur (1998). The Sixties: Cultural Revolution in Britain, France, Italy, and the United States, c.1958-c.1974. Oxford University Press. pp. 247–248. ISBN 9780192100221.

- O'Brien, Michael (2005). John F. Kennedy: A Biography. The most detailed scholarly biography excerpt and text search

- Olson, James S. (2000). Historical Dictionary of the 1950s. online edition

- Pach, Chester J.; Richardson, Elmo (1991). Presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) The standard historical survey - Parmet, Herbert S. (1972). Eisenhower and the American Crusades. online edition, scholarly biography

- Patterson, James T. (1988). Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974. Winner of the Bancroft prize in history

- Patterson, James T. (2005). Restless Giant: The United States from Watergate to Bush v. Gore. Survey by leading scholar

- Reichard, Gary W. (2004). Politics As Usual: The Age of Truman and Eisenhower (2nd ed.). 213pp; short survey

- Sundquist, James L. (1968). Politics and Policy: The Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson Years. Excellent analysis of the major political issues of the era.

- Walker, J. Samuel (1997). Prompt and Utter Destruction: Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs against Japan. online complete edition

- Young, William H. (2004). The 1950s. American Popular Culture Through History.