Nuclear power in the United States: Difference between revisions

→History: expand, based on a comment at Talk:Nuclear power |

|||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

In the early afternoon of Dec. 20, 1951, scientist [[Walter Zinn]] and a small crew of assistants witnessed a row of four light bulbs light up in a nondescript brick building in the eastern Idaho desert. Electricity from a generator connected to Experimental Breeder Reactor-I (EBR-I) flowed through them. This was the first time that a usable amount of electrical power had ever been generated from nuclear fission. Only days afterward, the reactor produced all the electricity needed for the entire EBR complex.<ref>[http://www.inl.gov/proving-the-principle/chapter_06.pdf Proving the Principle: Chapter 6]</ref> One ton of natural uranium can produce more than 40 million kilowatt-hours of electricity — this is equivalent to burning 16,000 tons of coal or 80,000 barrels of oil.<ref>[http://web.ead.anl.gov/uranium/guide/facts/ Uranium Facts]</ref> More central to EBR-I’s purpose than just generating electricity, however, was its role in proving that a reactor could create more nuclear fuel as a byproduct than it consumed during operation. In 1953, tests verified that this was the case.<ref>[https://inlportal.inl.gov/portal/server.pt/document/43081/ebr1_4_pdf_%282%29 Experimental Breeder Reactor I]</ref> The site of this event is memorialized as a Registered [[National_historic_landmark|National Historic Landmark]], open to the public every day [[Memorial_day|Memorial Day]] through [[Labor_day|Labor Day]]. |

In the early afternoon of Dec. 20, 1951, scientist [[Walter Zinn]] and a small crew of assistants witnessed a row of four light bulbs light up in a nondescript brick building in the eastern Idaho desert. Electricity from a generator connected to Experimental Breeder Reactor-I (EBR-I) flowed through them. This was the first time that a usable amount of electrical power had ever been generated from nuclear fission. Only days afterward, the reactor produced all the electricity needed for the entire EBR complex.<ref>[http://www.inl.gov/proving-the-principle/chapter_06.pdf Proving the Principle: Chapter 6]</ref> One ton of natural uranium can produce more than 40 million kilowatt-hours of electricity — this is equivalent to burning 16,000 tons of coal or 80,000 barrels of oil.<ref>[http://web.ead.anl.gov/uranium/guide/facts/ Uranium Facts]</ref> More central to EBR-I’s purpose than just generating electricity, however, was its role in proving that a reactor could create more nuclear fuel as a byproduct than it consumed during operation. In 1953, tests verified that this was the case.<ref>[https://inlportal.inl.gov/portal/server.pt/document/43081/ebr1_4_pdf_%282%29 Experimental Breeder Reactor I]</ref> The site of this event is memorialized as a Registered [[National_historic_landmark|National Historic Landmark]], open to the public every day [[Memorial_day|Memorial Day]] through [[Labor_day|Labor Day]]. |

||

There has been considerable [[anti-nuclear]] opposition to the use of nuclear power in the U.S. The first U.S. reactor to face public opposition was [[Enrico Fermi Nuclear Generating Station|Fermi 1]] in 1957. It was built approximately 30 miles from Detroit and there was opposition from the [[United Auto Workers Union]].<ref>Michael D. Mehta (2005). [http://books.google.com.au/books?id=zVoPQCkGETEC&dq=antinuclear+protests&lr=&source=gbs_navlinks_s Risky business: nuclear power and public protest in Canada] Lexington Books, p. 35.</ref> [[Pacific Gas & Electric]] planned to build the first commercially viable nuclear power plant in the USA at [[Bodega Bay]], north of [[San Francisco]]. The proposal was controversial and conflict with local citizens began in 1958.<ref name=well>Paula Garb. [http://jpe.library.arizona.edu/volume_6/wellockvol6.htm Review of Critical Masses], ''Journal of Political Ecology'', Vol 6, 1999.</ref> The conflict ended in 1964, with the forced abandonment of plans for the power plant. Historian [[Thomas Wellock]] traces the birth of the [[anti-nuclear movement]] to the controversy over Bodega Bay.<ref name=well/> Attempts to build a nuclear power plant in [[Malibu, California|Malibu]] were similar to those at Bodega Bay and were also abandoned.<ref name=well/> Nuclear accidents continued into the 1960s with a small test reactor exploding at the [[SL-1|Stationary Low-Power Reactor Number One]] in Idaho Falls in January 1961 and a partial meltdown at the [[Enrico Fermi Nuclear Generating Station]] in Michigan in 1966.<ref name=bks/> In his 1963 book ''Change, Hope and the Bomb'', [[David Lilienthal]] criticized nuclear developments, particularly the nuclear industry's failure to address the [[High-level radioactive waste management|nuclear waste]] question. <ref name=rudig>Wolfgang Rudig (1990). ''Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy'', Longman, p. 61.</ref> [[J. Samuel Walker]], in his book ''[[Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective]]'', explains that the growth of the nuclear industry in the U.S. occurred in the 1970s as the [[environmental movement]] was being formed. Environmentalists saw the advantages of nuclear power in reducing air pollution, but were critical of nuclear technology on other grounds.<ref name=ten/> They were concerned about [[nuclear accident]]s, [[nuclear proliferation]], [[Economics of new nuclear power plants|high cost of nuclear power plants]], [[nuclear terrorism]] and [[radioactive waste disposal]].<ref name = bm>[[Brian Martin]]. [http://www.bmartin.cc/pubs/07sa.html Opposing nuclear power: past and present], ''Social Alternatives'', Vol. 26, No. 2, Second Quarter 2007, pp. 43-47.</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | By the end of the 1970s it became clear that nuclear power would not grow nearly as dramatically as once believed. This was particularly galvanized by the [[Three Mile Island accident]] in 1979. Eventually, more than 120 reactor orders were ultimately cancelled<ref>[http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL33442.pdf Nuclear Power: Outlook for New U.S. Reactors] p. 3.</ref> and the construction of new reactors ground to a halt. [[Al Gore]] has commented on the historical record and reliability of nuclear power in the United States: |

||

<blockquote> |

<blockquote> |

||

Of the 253 nuclear power reactors originally ordered in the United States from 1953 to 2008, 48 percent were canceled, 11 percent were prematurely shut down, 14 percent experienced at least a one-year-or-more outage, and 27 percent are operating without having a year-plus outage. Thus, only about one fourth of those ordered, or about half of those completed, are still operating and have proved relatively reliable.<ref>Al Gore (2009). ''[[Our Choice]]'', Bloomsbury, p. 157.</ref> |

Of the 253 nuclear power reactors originally ordered in the United States from 1953 to 2008, 48 percent were canceled, 11 percent were prematurely shut down, 14 percent experienced at least a one-year-or-more outage, and 27 percent are operating without having a year-plus outage. Thus, only about one fourth of those ordered, or about half of those completed, are still operating and have proved relatively reliable.<ref>Al Gore (2009). ''[[Our Choice]]'', Bloomsbury, p. 157.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 01:40, 14 March 2011

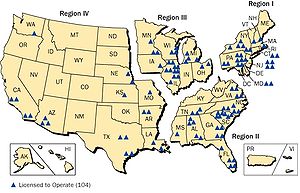

As of 2008, Nuclear power in the United States is provided by 104 (69 pressurized water reactors and 35 boiling water reactors) commercial nuclear power plants licensed to operate, producing a total of 806.2 TWh of electricity, which was 19.6% of the nation's total electric energy consumption in 2008.[1] The United States is the world's largest supplier of commercial nuclear power.

Ground has been broken on two new nuclear plants with a total of four reactors. The only reactor under construction in America, at Watts Bar, Tennessee, was begun in 1973 and may be completed in 2012. Of the 104 plants now operating in the U.S., ground was broken on all of them in 1974 or earlier.[2][3] In September 2010, Matthew Wald from the New York Times reported that "the nuclear renaissance is looking small and slow at the moment".[4]

History

Research into the peaceful uses of nuclear materials in the US began shortly after the end of the Second World War under the auspices of the Atomic Energy Commission, created by the Atomic Energy Act of 1946. Medical scientists were interested in the effect of radiation upon the fast-growing cells of cancer, and materials were given to them, while the military services led research into other peaceful uses.

In particular, the US Navy took the lead, seeing the opportunity to have ships that could steam around the world at high speeds without refueling being necessary for several decades, and the possibility of turning submarines into true full-time underwater vehicles. So, the Navy sent their "man in Engineering", then Captain Hyman Rickover, well known for his great technical talents in electrical engineering, power on board, and propulsion systems in addition to his skill in project management, to the AEC to start the Naval Reactors project. Rickover's work with the AEC led to the development of the Pressurized Water Reactor (PWR), the first naval model of which was installed in the submarine USS Nautilus. This made the boat capable of operating under water full time - demonstrating this principle by reaching the North Pole and surfacing through the Polar ice cap.

From the successful naval reactor program, plans were quickly developed for the use of reactor steam to drive turbines turning generators. On May 26, 1958 the first commercial nuclear power plant in the United States, Shippingport nuclear power plant, was opened by President Dwight D. Eisenhower as part of his Atoms for Peace program. As nuclear power continued to grow throughout the 1960s, the Atomic Energy Commission anticipated that more than 1,000 reactors would be operating in the United States by 2000.[5] As the industry continued to expand, the Atomic Energy Commission's development and regulatory functions were separated in 1974; the Department of Energy absorbed research and development, while the regulatory branch was spun off and turned into an Independent Commission known as the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (USNRC or simply NRC).

Much of what the world knows today about how nuclear reactors behave and misbehave was discovered at what is now Idaho National Laboratory. More than 50 reactors have been built at what is commonly called “the Site,” including the ones that gave the world its first usable amount of electricity produced from nuclear power and the power plant for the world’s first nuclear submarine. Although many are now decommissioned, these facilities represent the largest concentration of reactors in the world.[6] John Grossenbacher, current INL director, said, "The history of nuclear energy for peaceful application has principally been written in Idaho."[7]

In the early afternoon of Dec. 20, 1951, scientist Walter Zinn and a small crew of assistants witnessed a row of four light bulbs light up in a nondescript brick building in the eastern Idaho desert. Electricity from a generator connected to Experimental Breeder Reactor-I (EBR-I) flowed through them. This was the first time that a usable amount of electrical power had ever been generated from nuclear fission. Only days afterward, the reactor produced all the electricity needed for the entire EBR complex.[8] One ton of natural uranium can produce more than 40 million kilowatt-hours of electricity — this is equivalent to burning 16,000 tons of coal or 80,000 barrels of oil.[9] More central to EBR-I’s purpose than just generating electricity, however, was its role in proving that a reactor could create more nuclear fuel as a byproduct than it consumed during operation. In 1953, tests verified that this was the case.[10] The site of this event is memorialized as a Registered National Historic Landmark, open to the public every day Memorial Day through Labor Day.

There has been considerable anti-nuclear opposition to the use of nuclear power in the U.S. The first U.S. reactor to face public opposition was Fermi 1 in 1957. It was built approximately 30 miles from Detroit and there was opposition from the United Auto Workers Union.[11] Pacific Gas & Electric planned to build the first commercially viable nuclear power plant in the USA at Bodega Bay, north of San Francisco. The proposal was controversial and conflict with local citizens began in 1958.[12] The conflict ended in 1964, with the forced abandonment of plans for the power plant. Historian Thomas Wellock traces the birth of the anti-nuclear movement to the controversy over Bodega Bay.[12] Attempts to build a nuclear power plant in Malibu were similar to those at Bodega Bay and were also abandoned.[12] Nuclear accidents continued into the 1960s with a small test reactor exploding at the Stationary Low-Power Reactor Number One in Idaho Falls in January 1961 and a partial meltdown at the Enrico Fermi Nuclear Generating Station in Michigan in 1966.[13] In his 1963 book Change, Hope and the Bomb, David Lilienthal criticized nuclear developments, particularly the nuclear industry's failure to address the nuclear waste question. [14] J. Samuel Walker, in his book Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective, explains that the growth of the nuclear industry in the U.S. occurred in the 1970s as the environmental movement was being formed. Environmentalists saw the advantages of nuclear power in reducing air pollution, but were critical of nuclear technology on other grounds.[15] They were concerned about nuclear accidents, nuclear proliferation, high cost of nuclear power plants, nuclear terrorism and radioactive waste disposal.[16]

By the end of the 1970s it became clear that nuclear power would not grow nearly as dramatically as once believed. This was particularly galvanized by the Three Mile Island accident in 1979. Eventually, more than 120 reactor orders were ultimately cancelled[17] and the construction of new reactors ground to a halt. Al Gore has commented on the historical record and reliability of nuclear power in the United States:

Of the 253 nuclear power reactors originally ordered in the United States from 1953 to 2008, 48 percent were canceled, 11 percent were prematurely shut down, 14 percent experienced at least a one-year-or-more outage, and 27 percent are operating without having a year-plus outage. Thus, only about one fourth of those ordered, or about half of those completed, are still operating and have proved relatively reliable.[18]

Amory Lovins has also commented on the historical record of nuclear power in the United States:

Of all 132 U.S. nuclear plants built (52% of the 253 originally ordered), 21% were permanently and prematurely closed due to reliability or cost problems, while another 27% have completely failed for a year or more at least once. The surviving U.S. nuclear plants produce ~90% of their full-time full-load potential, but even they are not fully dependable. Even reliably operating nuclear plants must shut down, on average, for 39 days every 17 months for refueling and maintenance, and unexpected failures do occur too.[19]

A cover story in the February 11, 1985, issue of Forbes magazine commented on the overall management of the nuclear power program in the United States:

The failure of the U.S. nuclear power program ranks as the largest managerial disaster in business history, a disaster on a monumental scale … only the blind, or the biased, can now think that the money has been well spent. It is a defeat for the U.S. consumer and for the competitiveness of U.S. industry, for the utilities that undertook the program and for the private enterprise system that made it possible.[20]

The NRC reported "(...the Three Mile Island accident...) was the most serious in U.S. commercial nuclear power plant operating history, even though it led to no deaths or injuries to plant workers or members of the nearby community."[21] The World Nuclear Association reports that "...more than a dozen major, independent studies have assessed the radiation releases and possible effects on the people and the environment around TMI since the 1979 accident at TMI-2. The most recent was a 13-year study on 32,000 people. None has found any adverse health effects such as cancers which might be linked to the accident."[22] Other nuclear power incidents within the US (defined as safety-related events in civil nuclear power facilities between INES Levels 1 and 3[23]) include those at the Davis-Besse Nuclear Power Plant, which was the source of two of the top five highest conditional core damage frequency nuclear incidents in the United States since 1979, according to the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission.[24]

Several US nuclear power plants closed well before their design lifetimes, due to successful campaigns by anti-nuclear activist groups.[25] These include Rancho Seco in 1989 in California and Trojan in 1992 in Oregon. Humboldt Bay in California closed in 1976, 13 years after geologists discovered it was built on a fault (the Little Salmon Fault). Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant never operated commercially as an authorized Emergency Evacuation Plan could not be agreed on due the political climate after the Three Mile Island and Chernobyl accidents. The last permanent closure of a US nuclear power plant was in 1997.[1]

A large number of plants have recently received 20-year extensions to their licensed lifetimes. The average capacity factor for all US plants has improved from below 60% in the 1970s and 1980s, to 92% in 2007,[26] more than compensating for the retirement of older reactors.[27]

Safety and accidents

Regulation of nuclear power plants in the United States is done by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which divides the nation into 4 administrative divisions.

As of February 2009, the NRC requires that the design of new power plants ensures that the reactor containment would remain intact, cooling systems would continue to operate, and spent fuel pools would be protected, in the event of an aircraft crash. This is an issue that has gained attention since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. The regulation does not apply to the 104 commercial reactors now operating.[28] However, the containment structures of nuclear power plants are among the strongest structures ever built by mankind; independent studies have shown that existing plants would easily survive the impact of a large commercial jetliner without loss of structural integrity.[29]

The nuclear industry in the United States has maintained one of the best industrial safety records in the world with respect to all kinds of accidents. For 2008, the industry hit a new low of 0.13 industrial accidents per 200,000 worker-hours.[30] This is improved over 0.24 in 2005, which was still a factor of 14.6 less than the 3.5 number for all manufacturing industries.[31] Private industry has an accident rate of 1.3 per 200,000 worker hours.[32]

| Date | Location | Description | Cost (in millions 2006 $) |

|---|---|---|---|

| March 28, 1979 | Middletown, Pennsylvania, US | Loss of coolant and partial core meltdown, see Three Mile Island accident and Three Mile Island accident health effects | US$2,400 |

| March 9, 1985 | Athens, Alabama, US | Instrumentation systems malfunction during startup, which led to suspension of operations at all three Browns Ferry Units | US$1,830 |

| April 11, 1986 | Plymouth, Massachusetts, US | Recurring equipment problems force emergency shutdown of Boston Edison’s Pilgrim Nuclear Power Plant | US$1,001 |

| March 31, 1987 | Delta, Pennsylvania, US | Peach Bottom units 2 and 3 shutdown due to cooling malfunctions and unexplained equipment problems | US$400 |

| December 19, 1987 | Lycoming, New York, US | Malfunctions force Niagara Mohawk Power Corporation to shut down Nine Mile Point Unit 1 | US$150 |

| February 20, 1996 | Waterford, Connecticut, US | Leaking valve forces shutdown Millstone Nuclear Power Plant Units 1 and 2, multiple equipment failures found | US$254 |

| September 2, 1996 | Crystal River, Florida, US | Balance-of-plant equipment malfunction forces shutdown and extensive repairs at Crystal River Unit 3 | US$384 |

| February 16, 2002 | Oak Harbor, Ohio, US | Severe corrosion of control rod forces 24-month outage of Davis-Besse reactor | US$143 |

| February 1, 2010 | Vernon, Vermont, US | Deteriorating underground pipes from the Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Plant leak radioactive tritium into groundwater supplies | US$700 |

Fuel cycle

Uranium mining

The United States has the 4th greatest uranium reserves in the world. Domestic production increased until 1980, after which it declined sharply due to low uranium prices. In 2001 the United States mined only 5% of the uranium consumed by its nuclear power plants. The remainder was imported, principally from Russia and Australia.[35] After 2001, however, uranium prices steadily increased, which prompted increased production and revived mines.

Uranium enrichment

The United States Enrichment Corporation (USEC) performs all enrichment activities for U.S. commercial nuclear plants, using 11.3 million SWUs per year at its Paducah, Kentucky site. The USEC plant still uses gaseous diffusion enrichment, which has now been proved to be inferior to centrifuge enrichment. However, the capital cost of such a plant is so high that the plant will go through a few more years of operation before being replaced by a modern centrifuge plant.

Currently, demonstration activities are underway in Oak Ridge, Tennessee for a future centrifugal enrichment plant. The new plant will be called the American Centrifuge Plant, which has an estimate cost of 2.3 billion USD.[36]

Reprocessing

US policy forbade nuclear reprocessing inside the country from 1976 to 1981. Since the GNEP was proposed, several reprocessing proposals have been made. Most recently an environmental review initiated under the terms of the GNEP was cancelled, maintaining the status quo in the US for the time being.[37]

Disposal

In the United States, all power produced by nuclear energy pays a tax of 0.1 cents per kWh sold, in exchange for which the United States government takes responsibility for the high level nuclear waste. This tax has been collected since the beginning of the industry, but action by the government towards creation of a national geological repository was not taken until the 1990s and 2000s since all spent fuel is immediately stored in the spent fuel pools on site.

Recently, as plants continue to age, many of these pools have come near capacity, prompting creation of dry cask storage facilities as well. Several lawsuits between utilities and the government have also transpired over the cost of these facilities, because by law the government is required to foot the bill for actions that go beyond the spent fuel pool.

Since 1987, Yucca Mountain, in Nevada, had been the proposed site for the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository, but the project was shelved in 2009.[38]

Water use in nuclear power production

Once-through cooling systems, while once common, have come under attack for perceived damage to the environment. Wildlife can become trapped inside the cooling systems and killed, and the increased water temperature of the returning water can impact local ecosystems. Studies have failed to show any significant environmental impact from once-through systems, however, raising the question of whether the possible reduced environmental impact of recirculating systems is worth the cost of increased water consumption. Nonetheless, US EPA regulations continue to favor recirculating systems, even forcing some older power plants to replace existing once-through cooling systems with new recirculating systems.

A 2008 study by the Associated Press found that of the 104 nuclear reactors in the U.S., "... 24 are in areas experiencing the most severe levels of drought. All but two are built on the shores of lakes and rivers and rely on submerged intake pipes to draw billions of gallons of water for use in cooling and condensing steam after it has turned the plants’ turbines,"[40] much like all Rankine Cycle power plants. In the 2008 south east drought reactors are reduced to lower operating powers or forced to shutdown for safety.[40]

The Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station is located in a desert and purchases reclaimed wastewater for cooling.[41]

Organizations

Fuel vendors

The following companies have active Nuclear fuel fabrication facilities in the United States.[42] These are all light water fuel fabrication facilities because only LWRs are operating in the US. The US currently has no MOX fuel fabrication facilities, though Duke Energy has expressed intent of building one of a relatively small capacity.[43]

- Areva (formerly Areva NP) runs fabrication facilities in Lynchburg, Virginia and Richland, Washington. It also has a Generation III+ plant design, EPR (formerly the Evolutionary Power Reactor), which it plans to market in the US.[44]

- Westinghouse operates a fuel fabrication facility in Columbia, South Carolina,[45] which processes 1,600 metric tons Uranium (MTU) per year. It previously operated a nuclear fuel plant in Hematite, Missouri but has since closed it down.

- GE pioneered the BWR technology that has become widely used throughout the world. It formed the Global Nuclear Fuel joint venture in 1999 with Hitachi and Toshiba and later restructured into GE-Hitachi Nuclear Energy. It operates the fuel fabrication facility in Wilmington, North Carolina, with a capacity of 1,200 MTU per year.

Industry and academic

The American Nuclear Society (ANS) scientific and educational organization that has academic and industry members. The organization publishes a large amount of literature on nuclear technology in several journals. The ANS also has some offshoot organizations such as North American Young Generation in Nuclear (NA-YGN).

The Nuclear Energy Institute (NEI) is an industry group whose activities include lobbying, experience sharing between companies and plants, and provides data on the industry to a number of outfits.

Anti-nuclear power groups

Some sixty anti-nuclear power groups are operating, or have operated, in the United States. These include: Abalone Alliance, Clamshell Alliance, Greenpeace USA, Institute for Energy and Environmental Research, Musicians United for Safe Energy, Nuclear Control Institute, Nuclear Information and Resource Service, Public Citizen Energy Program, Shad Alliance, and the Sierra Club.

Debate about nuclear power in the U.S.

2005 Poll:Blue represents those in favor of nuclear power, gray represents undecided, yellow represents opposed to nuclear power

There has been considerable public and scientific debate about the use of nuclear power in the United States, mainly from the 1960s to the late 1980s, but also since about 2001 when talk of a nuclear renaissance began. There has been debate about issues such as nuclear accidents, radioactive waste disposal, nuclear proliferation, nuclear economics, and nuclear terrorism.[16]

Some scientists and engineers have expressed reservations about nuclear power, including: Barry Commoner, S. David Freeman, John Gofman, Arnold Gundersen, Mark Z. Jacobson, Amory Lovins, Arjun Makhijani, Gregory Minor, and Joseph Romm. Mark Z. Jacobson, professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford University, has said: "If our nation wants to reduce global warming, air pollution and energy instability, we should invest only in the best energy options. Nuclear energy isn't one of them".[46] Arnold Gundersen, chief engineer of Fairewinds Associates and a former nuclear power industry executive, has questioned the safety of the Westinghouse AP1000, a proposed third-generation nuclear reactor.[47] John Gofman, a nuclear chemist and doctor, raised concerns about exposure to low-level radiation in the 1960s and argued against commercial nuclear power in the U.S.[48]

Environmentalist Patrick Moore (environmentalist) spoke out against nuclear power in 1976,[49] but today he supports it, along with renewable energy sources.[50][51][52] In Australian newspaper The Age, he writes "Greenpeace is wrong — we must consider nuclear power".[53] He argues that any realistic plan to reduce reliance on fossil fuels or greenhouse gas emissions need increased use of nuclear energy.[50]

Environmentalist Stewart Brand wrote the book Whole Earth Discipline, which examines how nuclear power and some other technologies can be used as tools to address global warming.[54] Bernard Cohen, Professor Emeritus of Physics at the University of Pittsurgh, calculates that nuclear power is many times safer than other forms of power generation.[55]

Recent developments

In recent years, there has been a renewed interest in nuclear power in the US. This has been facilitated in part by the federal government with the Nuclear Power 2010 Program, which coordinates efforts for building new nuclear power plants,[56] and the Energy Policy Act which makes provisions for nuclear and oil industries.[57][58]

A series of Gallup polls from 1994 to 2009 found support for nuclear energy in the United States varying from 46% to 59%, with significant opinion differences between genders, income groups, and political affiliation.[59]

The prospect of a "nuclear renaissance" has revived debate about the nuclear waste issue. There is an "international consensus on the advisability of storing nuclear waste in deep underground repositories",[60] but no country in the world has yet opened such a site.[60][61][62][63][64][65] The Obama administration has disallowed reprocessing of nuclear waste, citing nuclear proliferation concerns.[37]

2008

On August 26, 2008, it was reported that The Shaw Group and Westinghouse would construct a factory at the Port of Lake Charles at Lake Charles, Louisiana to build components for the Westinghouse AP1000 nuclear reactor.[66] On October 23, 2008, it was reported that Northrop Grumman and Areva were planning to construct a factory in Newport News, Virginia to build nuclear reactors.[67]

2009

As of March 9, 2009, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission had received applications for permission to construct 26 new nuclear power reactors[68] with applications for another 7 expected.[69][70] Six of these reactors have actually been ordered.[71] In addition, the Tennessee Valley Authority petitioned to restart construction on the first two units at Bellefonte. However not all of this new capacity will necessarily be built, with some applications being made to keep future options open and reserving places in a queue for government incentives available for up to the first three plants based on each innovative reactor design.[69]

In May 2009, John Rowe, chairman of Exelon, which operates 17 nuclear reactors, said he would cancel or delay construction of two new reactors in Texas without federal loan guarantees.[61] U.S. nuclear power developers are increasingly looking for new partners to share the high costs and risks of building new reactors.[72]

As of July 2009[update], the proposed Victoria County Nuclear Power Plant has been delayed, as the project proved difficult to finance.[73] As of April 2009[update], AmerenUE has suspended plans to build its proposed plant in Missouri because the state Legislature would not allow it to charge consumers for some of the project's costs before the plant's completion. The New York Times has reported that without that "financial and regulatory certainty," the company has said it could not proceed.[74] Previously, MidAmerican Energy Company decided to "end its pursuit of a nuclear power plant in Payette County, Idaho." MidAmerican cited cost as the primary factor in their decision.[75]

2010

On February 16, 2010, President Barack Obama announced loan guarantees for two new reactors at Georgia Power's Vogtle NPP.[76] If the project goes forward, these would be the first plants built in the United States since the 1970s.[77] The reactors are "just the first of what we hope will be many new nuclear projects," said Carol Browner, director of the White House Office of Energy and Climate Change Policy.

Also in February 2010, Vermont Senate voted 26 to 4 to block operation of the Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Plant after 2012, citing radioactive tritium leaks, misstatements in testimony by plant officials, a cooling tower collapse in 2007, and other problems. By state law, the renewal of the operating license must be approved by both houses of the legislature for the nuclear power plant to continue operation.[78]

Other than the Vogtle project, ground has been broken on just one other reactor, in South Carolina, as of September 2010. The prospects of a proposed project in Texas, South Texas 3 & 4, have been dimmed by disunity among the partners. Two other reactors in Texas, four in Florida and one in Missouri have all been "moved to the back burner, mostly because of uncertain economics".[4] Constellation Energy has "pulled the plug" on building a new reactor at its Calvert Cliffs Nuclear Power Plant despite a promised $7.5 billion loan guarantee from the Department of Energy".[79][80] Matthew Wald from the New York Times has reported that "the nuclear renaissance is looking small and slow at the moment".[4]

In December 2010, The Economist reported that the demand for nuclear power is softening in America.[3] In recent years, utilities have shown an interest in about 30 new reactors, but the number with any serious prospect of being built as of the end of 2010 is now about a dozen, as some companies have withdrawn their applications for licenses to build.[2][81] Exelon has withdrawn its application for a license for a twin-unit nuclear plant in Victoria County, Texas, citing lower electricity demand projections. The decision has left the country’s largest nuclear operator without a direct role in what the nuclear industry hopes is a nuclear renaissance.[82] Ground has been broken on two new nuclear plants with a total of four reactors. The Obama administration is seeking the expansion of a loan guarantee program but as of December 2010 has been unable to commit all of the loan guarantee money already approved by Congress. Since talk a few years ago of a “nuclear renaissance”, gas prices have fallen and old reactors are getting license extensions. The only reactor under construction in America, at Watts Bar, Tennessee, is an an old unit which was begun in 1973, whose construction was suspended in 1988, and was resumed in 2007.[83] It may be completed in 2012. Of the 104 plants now operating in the U.S., ground was broken on all of them in 1974 or earlier.[2][3]

See also

References

- ^ a b Nuclear Energy Review, US Energy Information Administration, June 26, 2009.

- ^ a b c Matthew L. Wald (December 7, 2010). Nuclear ‘Renaissance’ Is Short on Largess The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Team France in disarray: Unhappy attempts to revive a national industry (December 2, 2010), The Economist.

- ^ a b c Matthew L. Wald. Aid Sought for Nuclear Plants Green, September 23, 2010.

- ^ Parker, Larry and Holt, Mark (March 9, 2007). Nuclear power: Outlook for new U.S. reactors CRS Report for Congress.

- ^ INL History

- ^ John Grossenbacher's Remarks at the Idaho Falls City Club April 30, 2010

- ^ Proving the Principle: Chapter 6

- ^ Uranium Facts

- ^ Experimental Breeder Reactor I

- ^ Michael D. Mehta (2005). Risky business: nuclear power and public protest in Canada Lexington Books, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Paula Garb. Review of Critical Masses, Journal of Political Ecology, Vol 6, 1999.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

bkswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Wolfgang Rudig (1990). Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy, Longman, p. 61.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

tenwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Brian Martin. Opposing nuclear power: past and present, Social Alternatives, Vol. 26, No. 2, Second Quarter 2007, pp. 43-47.

- ^ Nuclear Power: Outlook for New U.S. Reactors p. 3.

- ^ Al Gore (2009). Our Choice, Bloomsbury, p. 157.

- ^ Amory Lovins, Imran Sheikh, Alex Markevich (2009). Nuclear Power:Climate Fix or Folly p. 10.

- ^ "Nuclear Follies", a February 11, 1985 cover story in Forbes magazine.

- ^ U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Federal Government of the United States (2009-08-11). "Backgrounder on the Three Mile Island Accident". Retrieved 2010-07-17.

{{cite web}}: Check|first=value (help) - ^ World Nuclear Association (2001-03, update 2010-01). "Three Mile Island Accident Factsheet". Retrieved 2010-07-17.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ International Atomic Energy Agency. "INES - International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale". Retrieved 2010-07-17.)

- ^ Nuclear Regulatory Commission (2004-09-16). "Davis-Besse preliminary accident sequence precursor analysis" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-06-14. and Nuclear Regulatory Commission (2004-09-20). "NRC issues preliminary risk analysis of the combined safety issues at Davis-Besse". Retrieved 2006-06-14.

- ^ "Shutting Down Rancho Seco". Time. 1989-06-19.

- ^ "Nuclear power plant operations since 1957", US Energy Information Administration, 2007. File:Fig 9-2 Nuclear Power Plant Operations.jpg

- ^ Findings: Energy Lessons by John Tierney, New York Times, published October 6, 2008.

- ^ Reactor Rule Made With 9/11 in Mind

- ^ http://www.nei.org/newsandevents/aircraftcrashbreach

- ^ Reuters. Nuclear Industry's Safety, Operating Performance Remained Top-Notch in '08, WANO Indicators Show. March 27, 2009.

- ^ Charles Fergus. Research Penn State. Are today's nuclear power plants safe?

- ^ [1]

- ^ Benjamin K. Sovacool. A Critical Evaluation of Nuclear Power and Renewable Electricity in Asia, Journal of Contemporary Asia, Vol. 40, No. 3, August 2010, pp. 393–400.

- ^ Benjamin K. Sovacool (2009). The Accidental Century - Prominent Energy Accidents in the Last 100 Years

- ^ Warren I Finch (2003) Uranium-fuel for nuclear energy 2002, US Geological Survey, Bulletin 2179-A.

- ^ "Uranium Enrichment — The American Centrifuge". USEC Inc. 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ^ a b http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v460/n7252/full/460152b.html

- ^ "Nuclear industry to fight Yucca Mountain bill".

- ^ http://www.eia.doe.gov/cneaf/electricity/epm/table1_1.html

- ^ a b http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/22804065//

- ^ http://www.fastcompany.com/1604109/attention-cities-you-can-sell-your-excess-wastewater-to-nuclear-power-plants

- ^ :) "World Nuclear Fuel Facilities". WISE Uranium Project. last updated 14 May 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Duke Power Granted License Amendment by Nuclear Regulatory Commission To Use MOX Fuel". Duke Energy. March 3, 2005. Archived from the original on 2007-12-06. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ^ "EPR: Generation III+ Performance" (PDF). 6 September 2007. Retrieved 2008-05-15. [dead link]

- ^ "Uranium Ash at Westinghouse Nuclear Fuel Plant Draws Fine". Environment News Service. 2004.

- ^ Mark Z. Jacobson. Nuclear power is too risky CNN, February 22, 2010.

- ^ Robynne Boyd. Safety Concerns Delay Approval of the First U.S. Nuclear Reactor in Decades Scientific American, July 29, 2010.

- ^ Obituary: John W. Gofman, 88, Scientist and Advocate for Nuclear Safety Dies New York Times, August 26, 2007.

- ^ Patrick Moore, Assault on Future Generations, Greenpeace report, p47-49, 1976 - pdf [2]

- ^ a b Moore, Patrick (2006-04-16). "Going Nuclear". Washington Post.

- ^ Washington Post Article, Sunday, April 16, 2006 - Going Nuclear [3]

- ^ The Independent, Nuclear energy? Yes please! [4]

- ^ The Age Greenpeace is wrong — we must consider nuclear power, article by Patrick Moore,December 10, 2007 [5]

- ^ Stewart Brand (2009). Whole Earth Discipline: An Ecopragmatist Manifesto. Viking. ISBN 9780670021215.

- ^ http://www.phyast.pitt.edu/~blc/book/BOOK.html

- ^ "The Daily Sentinel." Commission, City support NuStart. Retrieved on December 1, 2006

- ^ "US energy bill favors new build reactors, new technology". Nuclear Engineering International. 12 August 2005. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

- ^ Michael Grunwald and Juliet Eilperin (July 30, 2005). "Energy Bill Raises Fears About Pollution, Fraud Critics Point to Perks for Industry". Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Gallup "Support for nuclear energy inches up to new high," 20 March 2009, accessed 31 August 2010.

- ^ a b Al Gore (2009). Our Choice, Bloomsbury, pp. 165-166.

- ^ a b US nuclear industry tries to hijack Obama's climate change bill

- ^ Motevalli, Golnar (Jan 22, 2008). "Nuclear power rebirth revives waste debate". Reuters. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ^

"A Nuclear Power Renaissance?". Scientific American. April 28, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^

von Hippel, Frank N. (April 2008). "Nuclear Fuel Recycling: More Trouble Than It's Worth". Scientific American. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Is the Nuclear Renaissance Fizzling?

- ^ Louisiana goes nuclear, cnn.com, August 26, 2008

- ^ Joint venture will build nuclear reactors in Newport News, The Virginian-Pilot, October 23, 2008

- ^ Combined License Applications for New Reactors

- ^ a b Chris Gadomski (20 February 2009). "Will nuclear rebound?". Nuclear Engineering International. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- ^ Map of new nuclear units

- ^ Shaw, Westinghouse sign nuke deal

- ^ US Nuclear-Power Projects Court New Partners

- ^ Exelon delays plan for Texas nuclear plant

- ^ A key energy industry nervously awaits its 'rebirth'

- ^ MidAmerican drops Idaho nuclear project due to cost

- ^ McCaffrey, Shannon (February 16, 2010). "Georgia Power still increasing rates". Associated Press. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- ^ A Comeback for Nuclear Power? New York Times, February 16, 2010.

- ^ Matthew L. Wald. Vermont Senate Votes to Close Nuclear Plant The New York Times, February 24, 2010.

- ^ Darren Goode. Constellation pulls plug on nuke reactor and $7.5 billion DOE loan The Hill, 9 October 2010.

- ^ Peter Behr. Constellation Pullout From Md. Nuclear Venture Leaves Industry Future Uncertain The New York Times, October 11, 2010.

- ^ Nuclear power in America: Constellation's cancellation, (October 16, 2010), The Economist, p. 61.

- ^ Matthew L. Wald (August 31, 2010). A Nuclear Giant Moves Into Wind The New York Times.

- ^ United States of America: Nuclear Power Reactors - By Status

External links

- Comment: A US nuclear future? Nature, Vol. 467, 23 September 2010, pp. 391–393.

- World Nuclear Association

- U.S. Nuclear Power Plant Statistical Information

- World Nuclear Association: Nuclear energy in the world

- The Nuclear Energy Institute: The policy organization of the nuclear energy and technologies industry

- Nuclear power plant operators in the United States (SourceWatch).