Pion: Difference between revisions

m +parity |

|||

| Line 118: | Line 118: | ||

Theoretical work by [[Hideki Yukawa]] in 1935 had predicted the existence of [[meson]]s as the carrier particles of the [[strong nuclear force]]. From the range of the strong nuclear force (inferred from the radius of the [[atomic nucleus]]), Yukawa predicted the existence of a particle having a mass of about 100 MeV. Initially after its discovery in 1936, the [[muon]] (initially called the "mu meson") was thought to be this particle, since it has a mass of 106 MeV. However, later particle physics experiments showed that the muon did not participate in the strong nuclear interaction. In modern terminology, this makes the muon a [[lepton]], and not a true meson. |

Theoretical work by [[Hideki Yukawa]] in 1935 had predicted the existence of [[meson]]s as the carrier particles of the [[strong nuclear force]]. From the range of the strong nuclear force (inferred from the radius of the [[atomic nucleus]]), Yukawa predicted the existence of a particle having a mass of about 100 MeV. Initially after its discovery in 1936, the [[muon]] (initially called the "mu meson") was thought to be this particle, since it has a mass of 106 MeV. However, later particle physics experiments showed that the muon did not participate in the strong nuclear interaction. In modern terminology, this makes the muon a [[lepton]], and not a true meson. |

||

In 1947, the first true mesons, the charged pions, were found by the collaboration of [[Cecil Powell]], [[César Lattes]], [[Giuseppe Occhialini]], ''et. al.'', at the [[University of Bristol]], in [[England]]. Since the advent of [[particle accelerator]]s had not yet come, high-energy subatomic particles were only obtainable from atmospheric [[cosmic ray]]s. [[Photographic emulsion]]s, which used the [[gelatin-silver process]], were placed for long periods of time in sites located at high altitude mountains, first at [[Pic du Midi de Bigorre]] in the [[Pyrenees]], and later at [[Chacaltaya]] in the [[Andes Mountains]], where they were impacted by cosmic rays. |

In 1947, the first true mesons, the charged pions, were found by the collaboration of [[Cecil Powell]], [[César Lattes]], [[Giuseppe Occhialini]], ''et. al.'', at the [[University of Bristol]], in [[England]]. Since the advent of [[particle accelerator]]s had not yet come, high-energy subatomic particles were only obtainable from atmospheric [[cosmic ray]]s. [[Photographic emulsion]]s, which used the [[gelatin-silver process]], were placed for long periods of time in sites located at high altitude mountains, first at [[Pic du Midi de Bigorre]] in the [[Pyrenees]], and later at [[Chacaltaya]] in the [[Andes Mountains]], where they were impacted by cosmic rays. |

||

After the development of the [[photographic plate]]s, [[microscope|microscopic]] inspection of the emulsions revealed the tracks of charged subatomic particles. Pions were first identified by their unusual "double meson" tracks, which were left by their decay into another "meson". (It was actually the "muon". Note that the muon is not classified as a meson in modern particle physics.) In 1948, Lattes, [[Eugene Gardner]], and their team first artificially produced pions at the [[University of California at Berkeley|University of California]]'s [[cyclotron]] in [[Berkeley, California]], by bombarding [[carbon]] atoms with high-speed [[alpha particle]]s. |

After the development of the [[photographic plate]]s, [[microscope|microscopic]] inspection of the emulsions revealed the tracks of charged subatomic particles. Pions were first identified by their unusual "double meson" tracks, which were left by their decay into another "meson". (It was actually the "muon". Note that the muon is not classified as a meson in modern particle physics.) In 1948, Lattes, [[Eugene Gardner]], and their team first artificially produced pions at the [[University of California at Berkeley|University of California]]'s [[cyclotron]] in [[Berkeley, California]], by bombarding [[carbon]] atoms with high-speed [[alpha particle]]s. Further advanced theoretical work was carried out by [[Riazuddin (physicist)|Riazuddin]] in 1959 who analyzed the charge radius of the pion of {{SubatomicParticle|Pion+-}}− {{SubatomicParticle|Pion0}} mass difference<ref>{{Cite journal |

||

| last =Riazuddin |

|||

| first = |

|||

| authorlink =Riazuddin (physicist) |

|||

| coauthors = |

|||

| title =Charge Radius of Pion |

|||

| journal =Physics Review and The American Physical Society |

|||

| volume =114 |

|||

| issue =4 |

|||

| pages =61/100 |

|||

| publisher =Riazuddin, Department of Mathematics of Imperial College of Science and Technology, London, England. |

|||

| location =London, England, United Kingdom |

|||

| date =May of 1959 |

|||

| url =http://prola.aps.org/abstract/PR/v114/i4/p1184_1 |

|||

| issn = |

|||

| doi = |

|||

| id = |

|||

| accessdate =2011 }}</ref>. The mass difference can be found to be of the order of magnitude {{nowrap|0.46×10<sup>−13</sup>cm - 0.56×10<sup>−13</sup>}}cm. |

|||

[[Nobel Prize in Physics|Nobel Prizes in Physics]] were awarded to Yukawa in 1949 for his theoretical prediction of the existence of mesons, and to [[Cecil Powell]] in 1950 for developing and applying the technique of particle detection using [[photographic emulsion]]s. |

[[Nobel Prize in Physics|Nobel Prizes in Physics]] were awarded to Yukawa in 1949 for his theoretical prediction of the existence of mesons, and to [[Cecil Powell]] in 1950 for developing and applying the technique of particle detection using [[photographic emulsion]]s. |

||

Since the neutral pion is not [[electric charge|electrically charged]], it is more difficult to detect and observe than the charged pions are. Neutral pions do not leave tracks in photographic emulsions, and neither do they in Wilson [[cloud chamber]]s. The existence of the neutral pion was inferred from observing its decay products from [[cosmic ray]]s, a so-called "soft component" of slow electrons with photons. The {{SubatomicParticle|Pion0}} was identified definitively at the University of California's cyclotron in 1950 by observing its decay into two photons. Later in the same year, they were also observed in cosmic-ray balloon experiments at Bristol University. |

Since the neutral pion is not [[electric charge|electrically charged]], it is more difficult to detect and observe than the charged pions are. Neutral pions do not leave tracks in photographic emulsions, and neither do they in Wilson [[cloud chamber]]s. The existence of the neutral pion was inferred from observing its decay products from [[cosmic ray]]s, a so-called "soft component" of slow electrons with photons. The {{SubatomicParticle|Pion0}} was identified definitively at the University of California's cyclotron in 1950 by observing its decay into two photons. Later in the same year, they were also observed in cosmic-ray balloon experiments at Bristol University. |

||

Revision as of 04:00, 25 February 2011

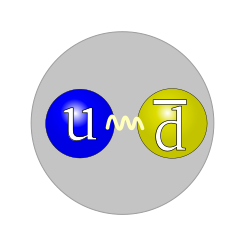

The quark structure of the pion. | |

| Composition | π+ : u d π0 : ( u u - d d )/√2 π− : d u |

|---|---|

| Statistics | Bosonic |

| Family | Mesons |

| Interactions | Strong |

| Symbol | π+ , π0 , and π− |

| Theorized | Hideki Yukawa (1935) |

| Discovered | Cecil Powell, César Lattes, and Giuseppe Occhialini (1947) |

| Types | 3 |

| Mass | π± : 139.57018(35) MeV/c2 π0 : 134.9766(6) MeV/c2 |

| Electric charge | π+ : +1 e π0 : 0 e π− : −1 e |

| Spin | 0 |

| Parity | -1 |

In particle physics, a pion (short for pi meson, denoted with

π

) is any of three subatomic particles:

π0

,

π+

, and

π−

. Pions are the lightest mesons and they play an important role in explaining the low-energy properties of the strong nuclear force.

Basic properties

Pions are bosons with zero spin, and they are composed of first-generation quarks. In the quark model, an "up quark" and an anti-"down quark" make up a

π+

, whereas a "down quark" and an anti-"up quark" make up the

π−

, and these are the antiparticles of one another. The uncharged pions are combinations of an "up quark" with an anti-"up quark" or a "down quark" with an anti-"down quark", have identical quantum numbers, and hence they are only found in superpositions. The lowest-energy superposition of these is the

π0

, which is its own antiparticle. Together, the pions form a triplet of isospin. Each pion has isospin (I = 1) and third-component isospin equal to its charge (Iz = +1, 0 or −1).

Charged pion decays

The

π±

mesons have a mass of 139.6 MeV/c2 and a mean lifetime of 2.6×10−8 s. They decay due to the weak interaction. The primary decay mode of a pion, with probability 0.999877, is a purely leptonic decay into a muon and a muon neutrino:

The second most common decay mode of a pion, with probability 0.000123, is also a leptonic decay into an electron and the corresponding electron neutrino. This mode was discovered at CERN in 1958:

The suppression of the electronic mode, with respect to the muonic one, is given approximately (to within radiative corrections) by the ratio of the half-widths of the pion–electron and the pion–muon decay reactions:

and is a spin effect known as the helicity suppression. Measurements of the above ratio have been considered for decades to be tests of the so-called "V − A structure" (vector minus axial vector or left-handed lagrangian) of the charged "weak current" and of lepton universality. Experimentally this ratio is 1.230(4)×10−4.[1]

Besides the purely leptonic decays of pions, also observed have been some "structure-dependent radiative leptonic decays", and also the very rare beta decay of pions (with probability of about 10−8) with a neutral pion as the final state.

Neutral pion decays

The

π0

meson has a slightly smaller mass of 135.0 MeV/c2 and a much shorter mean lifetime of 8.4×10−17 s. This pion decays in an electromagnetic force process. The main decay mode, with probability 0.98798, is into two photons (two gamma ray photons in this case):

π0→ 2

γ

Its second most common decay mode, with probability 0.01198, is the so-called "Dalitz" decay into a photon and an electron–positron pair:

The rate at which pions decay is a prominent quantity in many sub-fields of particle physics, such as chiral perturbation theory. This rate is parametrized by the pion decay constant (ƒπ), which is about 90 MeV.

| Particle name | Particle symbol |

Antiparticle symbol |

Quark content[2] |

Rest mass (MeV/c2) | IG | JPC | S | C | B' | Mean lifetime (s) | Commonly decays to (>5% of decays) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pion[1] | π+ |

π− |

u d |

139.570 18(35) | 1− | 0− | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.6033 ± 0.0005 × 10−8 | μ+ + ν μ |

| Pion[3] | π0 |

Self | [a] | 134.976 6 ± 0.000 6 | 0− | 0−+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8.4 ± 0.6 × 10−17 | γ + γ |

[a] ^ Make-up inexact due to non-zero quark masses.[4]

History

Theoretical work by Hideki Yukawa in 1935 had predicted the existence of mesons as the carrier particles of the strong nuclear force. From the range of the strong nuclear force (inferred from the radius of the atomic nucleus), Yukawa predicted the existence of a particle having a mass of about 100 MeV. Initially after its discovery in 1936, the muon (initially called the "mu meson") was thought to be this particle, since it has a mass of 106 MeV. However, later particle physics experiments showed that the muon did not participate in the strong nuclear interaction. In modern terminology, this makes the muon a lepton, and not a true meson.

In 1947, the first true mesons, the charged pions, were found by the collaboration of Cecil Powell, César Lattes, Giuseppe Occhialini, et. al., at the University of Bristol, in England. Since the advent of particle accelerators had not yet come, high-energy subatomic particles were only obtainable from atmospheric cosmic rays. Photographic emulsions, which used the gelatin-silver process, were placed for long periods of time in sites located at high altitude mountains, first at Pic du Midi de Bigorre in the Pyrenees, and later at Chacaltaya in the Andes Mountains, where they were impacted by cosmic rays.

After the development of the photographic plates, microscopic inspection of the emulsions revealed the tracks of charged subatomic particles. Pions were first identified by their unusual "double meson" tracks, which were left by their decay into another "meson". (It was actually the "muon". Note that the muon is not classified as a meson in modern particle physics.) In 1948, Lattes, Eugene Gardner, and their team first artificially produced pions at the University of California's cyclotron in Berkeley, California, by bombarding carbon atoms with high-speed alpha particles. Further advanced theoretical work was carried out by Riazuddin in 1959 who analyzed the charge radius of the pion of

π±

−

π0

mass difference[5]. The mass difference can be found to be of the order of magnitude 0.46×10−13cm - 0.56×10−13cm.

Nobel Prizes in Physics were awarded to Yukawa in 1949 for his theoretical prediction of the existence of mesons, and to Cecil Powell in 1950 for developing and applying the technique of particle detection using photographic emulsions.

Since the neutral pion is not electrically charged, it is more difficult to detect and observe than the charged pions are. Neutral pions do not leave tracks in photographic emulsions, and neither do they in Wilson cloud chambers. The existence of the neutral pion was inferred from observing its decay products from cosmic rays, a so-called "soft component" of slow electrons with photons. The

π0

was identified definitively at the University of California's cyclotron in 1950 by observing its decay into two photons. Later in the same year, they were also observed in cosmic-ray balloon experiments at Bristol University.

The pion also plays a role in cosmology by imposing an upper limit on the energies of cosmic rays through the Greisen–Zatsepin–Kuzmin limit.

In the modern understanding of the strong force interaction, called "quantum chromodynamics", pions are considered to be the pseudo Nambu-Goldstone bosons of spontaneously broken chiral symmetry. This explains why the three kinds of pion's masses are considerably less than the masses of the other true mesons, such as the

η′

meson (958 MeV). If their constituent quarks were massless particles, hypothetically, making the chiral symmetry exact, then calculations with the Goldstone theorem would give all pions zero masses. In reality, since all quarks actually have nonzero masses, the pions also have nonzero rest masses.

The use of pions in medical radiation therapy, such as for cancer, was explored at a number of research institutions, including at the Los Alamos National Laboratory's Meson Physics Facility, which treated 228 patients between 1974 and 1981 in New Mexico,[6] and the TRIUMF laboratory in Vancouver, British Columbia.[7]

Theoretical overview

The pion can be thought of as the particle that mediates the interaction between a pair of nucleons. This interaction is attractive: it pulls the nucleons together. Written in a non-relativistic form, it is called the Yukawa potential. The pion, being spinless, has kinematics described by the Klein–Gordon equation. In the terms of quantum field theory, the effective field theory Lagrangian describing the pion-nucleon interaction is called the Yukawa interaction.

The nearly identical masses of

π±

and

π0

imply that there must be a symmetry at play; this symmetry is called the SU(2) flavour symmetry or isospin. The reason that there are three pions,

π+

,

π−

and

π0

, is that these are understood to belong to the triplet representation or the adjoint representation 3 of SU(2). By contrast, the up and down quarks transform according to the fundamental representation 2 of SU(2), whereas the anti-quarks transform according to the conjugate representation 2*.

With the addition of the strange quark, one can say that the pions participate in an SU(3) flavour symmetry, belonging to the adjoint representation 8 of SU(3). The other members of this octet are the four kaons and the eta meson.

Pions are pseudoscalars under a parity transformation. Pion currents thus couple to the axial vector current and pions participate in the chiral anomaly.

See also

References

- ^ a b C. Amsler et al.. (2008): Particle listings –

π±

- ^ C. Amsler et al.. (2008): Quark Model

- ^ C. Amsler et al.. (2008): Particle listings –

π0

- ^ Griffiths, David J. (1987). Introduction to Elementary Particles. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-60386-4.

- ^ Riazuddin (May of 1959). "Charge Radius of Pion". Physics Review and The American Physical Society. 114 (4). London, England, United Kingdom: Riazuddin, Department of Mathematics of Imperial College of Science and Technology, London, England.: 61/100. Retrieved 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ von Essen CF, Bagshaw MA, Bush SE, Smith AR, Kligerman MM (1987). "Long-term results of pion therapy at Los Alamos". Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 13 (9): 1389–98. PMID 3114189.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "TRIUMF: Cancer Therapy with Pions".

Further reading

- Gerald Edward Brown and A. D. Jackson, The Nucleon-Nucleon Interaction, (1976) North-Holland Publishing, Amsterdam ISBN 0-7204-0335-9