Nova Scotia: Difference between revisions

Hantsheroes (talk | contribs) |

Hantsheroes (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 110: | Line 110: | ||

==== Halifax established ==== |

==== Halifax established ==== |

||

Despite the British [[Siege of Port Royal (1710)|Conquest of Acadia]] in 1710, Nova Scotia remained primarily occupied by Catholic Acadians and Mi'kmaq. To prevent the establishment of Protestant settlements in the region, Mi'kmaq raided the early British settlements of present-day [[Shelburne, Nova Scotia|Shelburne]] (1715) and [[Canso, Nova Scotia|Canso]] (1720). A generation later, [[Father Le Loutre's War]] began when [[Edward Cornwallis]] arrived to establish [[Halifax, Nova Scotia|Halifax]] with 13 transports on June 21, 1749.<ref>Grenier, John. The Far Reaches of Empire. War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 2008; Thomas Beamish Akins. History of Halifax, Brookhouse Press. 1895. (2002 edition). p 7</ref> By unilaterally establishing Halifax the British were violating earlier treaties with the Mi'kmaq (1726), which were signed after [[Dummer's War]].<ref>Wicken, p. 181; Griffith, p. 390; Also see http://www.northeastarch.com/vieux_logis.html</ref> The British quickly began to build other settlements. To guard against Mi'kmaq, Acadian and French attacks on the new protestant settlements, British fortifications were erected in Halifax (1749), Dartmouth (1750), Bedford (Fort Sackville) (1751), [[Lunenburg, Nova Scotia|Lunenburg]] (1753) and [[Lawrencetown, Nova Scotia|Lawrencetown]] (1754).<ref>John Grenier. ''The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760.'' Oklahoma University Press.</ref> |

Despite the British [[Siege of Port Royal (1710)|Conquest of Acadia]] in 1710, Nova Scotia remained primarily occupied by Catholic Acadians and Mi'kmaq. To prevent the establishment of Protestant settlements in the region, Mi'kmaq raided the early British settlements of present-day [[Shelburne, Nova Scotia|Shelburne]] (1715) and [[Canso, Nova Scotia|Canso]] (1720). A generation later, [[Father Le Loutre's War]] began when [[Edward Cornwallis]] arrived to establish [[Halifax, Nova Scotia|Halifax]] with 13 transports on June 21, 1749.<ref>Grenier, John. The Far Reaches of Empire. War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 2008; Thomas Beamish Akins. History of Halifax, Brookhouse Press. 1895. (2002 edition). p 7</ref> By unilaterally establishing Halifax the British were violating earlier treaties with the Mi'kmaq (1726), which were signed after [[Dummer's War]].<ref>Wicken, p. 181; Griffith, p. 390; Also see http://www.northeastarch.com/vieux_logis.html</ref> The British quickly began to build other settlements. To guard against Mi'kmaq, Acadian and French attacks on the new protestant settlements, British fortifications were erected in Halifax (1749), Dartmouth (1750), Bedford (Fort Sackville) (1751), [[Lunenburg, Nova Scotia|Lunenburg]] (1753) and [[Lawrencetown, Nova Scotia|Lawrencetown]] (1754).<ref>John Grenier. ''The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760.'' Oklahoma University Press.</ref> There were numerous Mi'kmaq and Acadian raids on these villages such as the [[Raid on Dartmouth (1751)]]. |

||

Within 18 months of establishing Halifax, the British also took firm control of peninsula Nova Scotia by building fortifications in all the major Acadian communities: present-day Windsor ([[Fort Edward (Nova Scotia)|Fort Edward)]]; Grand Pre (Fort Vieux Logis) and Chignecto ([[Fort Lawrence]]). (A British fort already existed at the other major Acadian centre of [[Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia]]. Cobequid remained without a fort.)<ref>John Grenier. ''The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760.'' Oklahoma University Press.</ref> |

Within 18 months of establishing Halifax, the British also took firm control of peninsula Nova Scotia by building fortifications in all the major Acadian communities: present-day Windsor ([[Fort Edward (Nova Scotia)|Fort Edward)]]; Grand Pre (Fort Vieux Logis) and Chignecto ([[Fort Lawrence]]). (A British fort already existed at the other major Acadian centre of [[Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia]]. Cobequid remained without a fort.)<ref>John Grenier. ''The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760.'' Oklahoma University Press.</ref> There were numerous Mi'kmaq and Acadian raids on these fortifications such as the [[Siege of Grand Pre]]. |

||

==== French and Indian War ==== |

==== French and Indian War ==== |

||

Revision as of 19:35, 29 January 2011

Nova Scotia | |

|---|---|

| Country | Canada |

| Confederation | July 1, 1867 (1st, with ON, QC, NB) |

| Government | |

| • Lieutenant-Governor | Mayann Francis |

| • Premier | Darrell Dexter |

| Legislature | Nova Scotia House of Assembly |

| Federal representation | Parliament of Canada |

| House seats | 11 of 338 (3.3%) |

| Senate seats | 10 of 105 (9.5%) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 969,383 |

| GDP | |

| • Rank | 7th |

| • Total (2009) | C$34.283 billion[1] |

| • Per capita | C$34,210 (11th) |

| Canadian postal abbr. | NS |

| Postal code prefix | |

| Rankings include all provinces and territories | |

45°13′N 62°42′W / 45.217°N 62.700°W

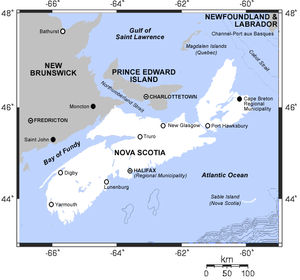

Nova Scotia (pronounced /ˌnoʊvə ˈskoʊʃə/; French: Nouvelle-Écosse; Scottish Gaelic: Alba Nuadh )[2] is one of Canada's three Maritime provinces and is the most populous province in Atlantic Canada. The provincial capital is Halifax. Nova Scotia is the second-smallest province in Canada with an area of 55,284 square kilometres (21,300 sq mi). As of 2009, the population is 940,397,[3] which makes Nova Scotia the second-most-densely populated province.

The province includes regions of the Mi'kmaq nation of Mi'kma'ki(mi'gama'gi).[4] Nova Scotia was already home to the Mi'kmaq people when the first European colonists arrived. In 1604, French colonists established the first permanent European settlement in Canada and the first north of Florida at Port Royal, founding what would become known as Acadia.

The British Conquest of Acadia happened in 1710. At this time the capital Port Royal was renamed Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia. The capital of Nova Scotia moved from Annapolis Royal to the newly established Halifax in 1749.

In 1763 Cape Breton Island and St. John's Island (now Prince Edward Island) became part of Nova Scotia. In 1769, St. John's Island became a separate colony. Nova Scotia included present-day New Brunswick until that province was established in 1784.[5]

In 1867 Nova Scotia was one of the four founding provinces of the Canadian Confederation.[6] While the Scottish desendents are perhaps the most well known, they only make up a minority of the population (29.3%). There are also Mi'kmaq, English, Irish, Acadian, African-Nova Scotians, German, Italian and many other peoples in Nova Scotia.

History

Mi'kmaq

The oldest evidence of humans in Nova Scotia indicates the Paleo-Indians were the first, approximately 11,000 years ago. Natives are believed to have been present in the area between 1,000 and 5,000 years ago. [citation needed] Mi'kmaq, the First Nations of the province and region, are their direct descendants.

The first European to arrive here was the Venetian explorer John Cabot who, sailing under the English flag, visited present-day Cape Breton in 1497.[7]

Seventeenth Century

Port Royal established

The first European settlement in Nova Scotia was established more than a century later in 1605. The French, led by Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Monts established the first capital for the colony Acadia at Port Royal.[8] Other than a few trading posts around the province, for the next seventy-five years Port Royal was virtually the only European settlement in Nova Scotia. Port Royal (later renamed Annapolis Royal) remained the capital of Acadia and later Nova Scotia for almost 150 years, prior to the founding of Halifax in 1749.

The first Scottish settlement in the Americas was Nova Scotia (1621). Eight years later, in 1629, Sir William Alexander established the first Scottish settlement at Port Royal. The colony's charter, in law, made Nova Scotia (defined as all land between Newfoundland and New England) a part of mainland Scotland. In 1631, under King Charles I, the Treaty of Suza returned Nova Scotia to the French.

Approximately seventy-five years after Port Royal was founded, Acadians migrated from the capital and established what would become the other major Acadian settlements before the Expulsion of the Acadians: Grand Pré, Chignecto, Cobequid and Pisiguit.

Until the Conquest of Acadia, the English made six attempts to conquer Acadia by defeating the capital. They finally defeated the French in the Siege of Port Royal (1710). Over the following fifty years, the French and their allies made six unsuccessful military attempts to regain the capital.

Civil War

From 1640–1645, Acadia was plunged into what some historians have described as a civil war. The war was between Port Royal, where Governor of Acadia Charles de Menou d'Aulnay de Charnisay was stationed, and present-day Saint John, New Brunswick, where Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour was stationed.[9]

In the war, there were four major battles. La Tour attacked d'Aulnay at Port Royal in 1640.[10] In response to the attack, D'Aulnay sailed out of Port Royal to establish a five month blockade of La Tour's fort at Saint John, which La Tour eventually defeated (1643). La Tour attacked d'Aulnay again at Port Royal in 1643. d'Aulnay and Port Royal ultimately won the war against La Tour with the 1645 siege of Saint John.[11] After d'Aulnay died (1650), La Tour re-established himself in Acadia.

King William's War

There were four colonial wars – the French and Indian Wars – between New England and New France before the British defeated the French in North America. During these wars, Nova Scotia/ Acadia was on the border and experienced many military conflicts. The first colonial war was King William's War.

During King William's War, military conflicts in Nova Scotia included: Battle of Port Royal (1690); Battle at Guysborough; a naval battle in the Bay of Fundy (Action of 14 July 1696); and the Raid on Chignecto (1696). At the end of the war England returned the territory to France in the Treaty of Ryswick.

Eighteenth Century

Queen Anne's War

The second colonial war was Queen Anne's War. During Queen Anne's War, the military conflicts in Nova Scotia included the Raid on Grand Pre, the Siege of Port Royal (1707), the Siege of Port Royal (1710) and the Battle of Bloody Creek (1711).

During Queen Anne's War the Conquest of Acadia was confirmed by the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713. At this time the British Empire considered present-day New Brunwick as part of Nova Scotia. France retained possession of Île St Jean (Prince Edward Island) and Île Royale (Cape Breton Island), on which it established a fortress at Louisbourg to guard the sea approaches to Quebec.

Dummer's War

During the escalation that preceded Dummer's War (1722–1725), Mi'kmaq raided the new fort at Canso, Nova Scotia (1720). Under potential siege, in May 1722, Lieutenant Governor John Doucett took 22 Mi'kmaq hostage at Annapolis Royal to prevent the capital from being attacked.[12] In July 1722 the Abenaki and Mi'kmaq created a blockade of Annapolis Royal, with the intent of starving the capital.[13] The natives captured 18 fishing vessels and prisoners from present-day Yarmouth to Canso. They also seized prisoners and vessels from the Bay of Fundy.

As a result of the escalating conflict, Massachusetts Governor Samuel Shute officially declared war on the Abenaki on July 22, 1722.[14] The first battle of Dummer's War happened in the Nova Scotia theatre.[15] In response to the blockade of Annapolis Royal, at the end of July 1722, New England launched a campaign to end the blockade and retrieve over 86 New England prisoners taken by the natives. One of these operations resulted in the Battle at Jeddore.[16] The next was a raid on Canso in 1723.[17] Then in July 1724 a group of sixty Mikmaq and Maliseets raided Annapolis Royal.[18]

The treaty that ended the war marked a significant shift in European relations with the Mi'kmaq and Maliseet. For the first time a European Empire formally acknowledged that its dominion over Nova Scotia would have to be negotiated with the region's indigenous inhabitants. The treaty was invoked as recently as 1999 in the Donald Marshall case.[19]

King George's War

The third colonial war was King Georges War. During King Georges War, military conflicts in Nova Scotia included: Raid on Canso; Siege of Annapolis Royal (1744); the Siege of Louisbourg (1745); the Duc d'Anville Expedition and the Battle of Grand Pré. During King Georges War, fortress Louisbourg was captured by American colonial forces in 1745, then returned by the British to France in 1748.

Halifax established

Despite the British Conquest of Acadia in 1710, Nova Scotia remained primarily occupied by Catholic Acadians and Mi'kmaq. To prevent the establishment of Protestant settlements in the region, Mi'kmaq raided the early British settlements of present-day Shelburne (1715) and Canso (1720). A generation later, Father Le Loutre's War began when Edward Cornwallis arrived to establish Halifax with 13 transports on June 21, 1749.[20] By unilaterally establishing Halifax the British were violating earlier treaties with the Mi'kmaq (1726), which were signed after Dummer's War.[21] The British quickly began to build other settlements. To guard against Mi'kmaq, Acadian and French attacks on the new protestant settlements, British fortifications were erected in Halifax (1749), Dartmouth (1750), Bedford (Fort Sackville) (1751), Lunenburg (1753) and Lawrencetown (1754).[22] There were numerous Mi'kmaq and Acadian raids on these villages such as the Raid on Dartmouth (1751).

Within 18 months of establishing Halifax, the British also took firm control of peninsula Nova Scotia by building fortifications in all the major Acadian communities: present-day Windsor (Fort Edward); Grand Pre (Fort Vieux Logis) and Chignecto (Fort Lawrence). (A British fort already existed at the other major Acadian centre of Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia. Cobequid remained without a fort.)[23] There were numerous Mi'kmaq and Acadian raids on these fortifications such as the Siege of Grand Pre.

French and Indian War

The fourth and final colonial war was the French and Indian War. During the war, military conflicts in Nova Scotia included: Battle of Fort Beauséjour; Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755); the Battle of Petitcodiac; the Raid on Lunenburg (1756); the Louisbourg Expedition (1757); Battle of Bloody Creek (1757); Siege of Louisbourg (1758), Petitcodiac River Campaign, Gulf of St. Lawrence Campaign (1758), St. John River Campaign, and Battle of Restigouche.

The British Conquest of Acadia happened in 1710. Over the next forty-five years the Acadians refused to sign an unconditional oath of allegiance to Britain. During this time period Acadians participated in various militia operations against the British and maintained vital supply lines to the French Fortress of Louisbourg and Fort Beausejour.[24]

During the French and Indian War, the British sought to neutralize any military threat Acadians posed and to interrupt the vital supply lines Acadians provided to Louisbourg by deporting Acadians from Acadia.[25]

The British began the Expulsion of the Acadians with the Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755). Over the next nine years over 12,000 Acadians were removed from Nova Scotia.[26]

The war ended and Britain had gained control over the entire Maritime region.

New England Planters

Between 1759 and 1768, about 8,000 New England Planters responded to Governor Charles Lawrence's request for settlers from the New England colonies.

American Revolution

Throughout the war, American privateers devastated the maritime economy by raiding many of the coastal communities. There were constant attacks by American privateers,[27] such as the Raid on Lunenburg (1782), numerous raids on Liverpool, Nova Scotia (October 1776, March 1777, September, 1777, May 1778, September 1780) and a raid on Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia (1781).[28]

American Privateers also raided Canso, Nova Scotia (1775). In 1779, American privateers returned to Canso and destroyed the fisheries, which were worth £50,000 a year to Britain.[29]

To guard against such attacks, the 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants) was garrisoned at forts around the Atlantic Canada. Fort Edward (Nova Scotia) in Windsor, Nova Scotia was the Regiment's headquarters to prevent a possible American land assault on Halifax from the Bay of Fundy. There was an American attack on Nova Scotia by land, the Battle of Fort Cumberland.

In 1781, as a result of the Franco-American alliance against Great Britain, there was also a naval engagement with a French fleet at Sydney, Nova Scotia, near Spanish River, Cape Breton.[30]

In 1784 the western, mainland portion of the colony was separated and became the province of New Brunswick, and the territory in Maine entered the control of the newly independent American state of Massachusetts. Cape Breton Island became a separate colony in 1784 only to be returned to Nova Scotia in 1820.

Loyalists

As a result of the British defeat in the American Revolution, approximately 30,000 United Empire Loyalists (American Tories) left the thirteen colonies and settled in Nova Scotia. Of these 30,000, 14,000 went to present-day New Brunswick and 16,000 went to Nova Scotia. Approximately 3,000 of this group were Black Loyalists.[31]

Nineteenth Century

War of 1812

During the War of 1812, Nova Scotia’s contribution to the war effort was communities either purchasing or building various privateer ships to lay siege to American vessels.[32] Three members of the community of Lunenburg, Nova Scotia purchased a privateer schooner and named it Lunenburg on August 8, 1814.[33] The Nova Scotian privateer vessel captured seven American vessels. The Liverpool Packet from Liverpool, Nova Scotia was another Nova Scotia privateer vessel that caught over fifty ships in the war - the most of any privateer in Canada.

Perhaps the most dramatic moment in the war for Nova Scotia was the HMS Shannon's led the captured American Frigate USS Chesapeake into Halifax Harbour (1813). Many of the prisoners were kept at Deadman's Island, Halifax.

Responsible government

Nova Scotia was the first colony in British North America and in the British Empire to achieve responsible government in January–February 1848 and become self-governing through the efforts of Joseph Howe. [citation needed]

-

Nova Scotia postage stamp (1851-1857). Printed in England. Also used in New Brunswick.

-

Nova Scotia stamp (issued 1860)

American Civil War

Thousands of Nova Scotians fought in the American Civil War (1861–1865), primarily for the North.[34] The British Empire (including Nova Scotia) was declared neutral in the struggle between the North and the South. As a result, Britain (and Nova Scotia) continued to trade with both the South and the North. Nova Scotia’s economy boomed during the civil war. To counter trade with the South, the North created a naval blockade. This blockade created tension between Britain and the North. Many blockade runners made their way back and forth between Halifax and the South. Nova Scotia was the site of two international incidents during the war: the Chesapeake Affair and the escape from Halifax Harbour of Confederate John Taylor Wood on the CSS Tallahassee.

The war left many fearful that the North might attempt to annex British North America, particularly after the Fenian raids began. In response, volunteer regiments were raised across Nova Scotia. One of the main reasons why Britain sanctioned the creation of Canada (1867) was to avoid another possible conflict with America and to leave the defence of Nova Scotia to a Canadian Government.[35]

Anti-Confederation campaign

Pro-Confederate premier Charles Tupper led Nova Scotia into the Canadian Confederation on July 1, 1867, along with New Brunswick and the Province of Canada.

The Anti-Confederation Party was led by Joseph Howe. Almost three months later, in the election of September 18, 1867, the Anti-Confederation Party, won 18 out of 19 federal seats, and 36 out of 38 seats in the provincial legislature. A motion passed by the Nova Scotia House of Assembly in 1868 refusing to recognise the legitimacy of Confederation has never been rescinded. With the great Hants County bi-election of 1869, Howe was successful in turning the province away from appealing confederation to simply seeking "better terms" within it. Repeal, as anti-confederation became known, would rear its head again in the 1880s, and transform into the Maritime Rights Movement in the 1920s. Some Nova Scotia flags flew at half mast on Dominion Day as late as that time.

Golden age of sail

Nova Scotia became a world leader in both building and owning wooden sailing ships in the second half of the 19th century. Nova Scotia produced internationally recognized ship builders Donald McKay and William Dawson Lawrence. The fame Nova Scotia achieved from sailors was assured when Joshua Slocum became the first man to sail single-handedly around the world (1895). This international attention continued into the following century with the many racing victories of the Bluenose schooner.

Nova Scotia was also the birthplace and home of Samuel Cunard, a British shipping magnate, born at Halifax, Nova Scotia, who founded the Cunard Line.

Geography

Nova Scotia is Canada's second-smallest province in area after Prince Edward Island. The province's mainland is the Nova Scotia peninsula surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, including numerous bays and estuaries. Nowhere in Nova Scotia is more than 67 km (42 mi) from the ocean.[36] Cape Breton Island, a large island to the northeast of the Nova Scotia mainland, is also part of the province, as is Sable Island, a small island notorious for its shipwrecks, approximately 175 km (110 mi) from the province's southern coast.

Climate

Nova Scotia lies in the mid-temperate zone and, although the province is almost surrounded by water, the climate is closer to continental rather than maritime. The temperature extremes of the continental climate are moderated by the ocean.

Described on the provincial vehicle-licence plate as Canada's Ocean Playground, the sea is a major influence on Nova Scotia's climate. Nova Scotia's cold winters and warm summers are modified and generally moderated by ocean influences. The province is surrounded by three major bodies of water, the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to the north, the Bay of Fundy to the west, and the Atlantic Ocean to the south and east.

While the constant temperature of the Atlantic Ocean moderates the climate of the south and east coasts of Nova Scotia, heavy ice build-up in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence makes winters colder in northern Nova Scotia; the shallowness of the Gulf's waters mean that they warm up more than the Atlantic Ocean in the summer, warming the summers in northern Nova Scotia. Summer officially lasts from the first Sunday in April to the Saturday before the last Sunday in October. Although Nova Scotia has a somewhat moderated climate, there have been some very intense heatwaves and cold snaps recorded over the past 160 years. The highest temperature ever recorded in the province was 38.3 °C (101 °F) on August 19, 1935 at Collegeville,[37] which is located about 15 km southwest of Antigonish. The coldest temperature ever recorded was −41.1 °C (−42 °F) on January 31, 1920 at Upper Stewiacke.[38]

The highest temperature ever recorded in the city of Halifax was 37.2 °C (99 °F) on July 10, 1912,[39] and the lowest was −29.4 °C (−21 °F) on Feb 18th, 1922.[40] For the city of Sydney, the highest temperature ever recorded was 36.7 °C (98 °F) on August 18, 1935,[41] and the lowest was −31.7 °C (−25 °F) on January 31, 1873,[42] and January 29, 1877 [43]

Rainfall changes from 140 centimetres (55 in) in the south to 100 centimetres (40 in) elsewhere. Nova Scotia is also very foggy in places, with Halifax averaging 196 foggy days per year[44] and Yarmouth 191.[45]

The average annual temperatures are:

- Spring from 1 °C (34 °F) to 17 °C (63 °F)

- Summer from 14 °C (57 °F) to 28 °C (82 °F)[46]

- Fall about 5 °C (41 °F) to 20 °C (68 °F)

- Winter about −20 °C (−4 °F) to 5 °C (41 °F)

Due to the ocean's moderating effect Nova Scotia is the warmest of the provinces in Canada.[citation needed] It has frequent coastal fog and marked changeability of weather from day to day. The main factors influencing Nova Scotia's climate are:

- The effects of the westerly winds

- The interaction between three main air masses which converge on the east coast

- Nova Scotia's location on the routes of the major eastward-moving storms

- The modifying influence of the sea.

Because Nova Scotia juts out into the Atlantic, it is prone to tropical storms and hurricanes in the summer and autumn. However due to the relatively cooler waters off the coast of Nova Scotia, tropical storms are usually weak by the time they reach Nova Scotia. There have been 33 such storms, including 12 hurricanes, since records were kept in 1871 – about once every four years. The last hurricane was category-one Hurricane Earl in September 2010, and the last tropical storm was Tropical Storm Noel in 2007 (downgraded from Hurricane Noel by the time the storm reached Nova Scotia).

Demographics

Population since 1851

| Year | Population | Five Year % change |

Ten Year % change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1851 | 276,854 | n/a | n/a |

| 1861 | 330,857 | n/a | 19.5 |

| 1871 | 387,800 | n/a | 17.2 |

| 1881 | 440,572 | n/a | 13.6 |

| 1891 | 450,396 | n/a | 2.2 |

| 1901 | 459,574 | n/a | 2.0 |

| 1911 | 492,338 | n/a | 7.1 |

| 1921 | 523,837 | n/a | 6.4 |

| 1931 | 512,846 | n/a | -2.1 |

| 1941 | 577,962 | n/a | 12.7 |

| 1951 | 642,584 | n/a | 11.2 |

| 1956 | 694,717 | 8.1 | n/a |

| 1961 | 737,007 | 6.1 | 14.7 |

| 1966 | 756,039 | 2.6 | 8.8 |

| 1971 | 788,965 | 4.4 | 7.0 |

| 1976 | 828,570 | 5.0 | 9.6 |

| 1981 | 847,442 | 2.3 | 7.4 |

| 1986 | 873,175 | 3.0 | 5.4 |

| 1991 | 899,942 | 3.1 | 6.2 |

| 1996 | 909,282 | 1.0 | 4.1 |

| 2001 | 908,007 | -0.1 | 0.9 |

| 2006 | 913,462 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| 2011 | 944,251 | 3.4 | 3.9 |

Top ten counties by population

| County | 2001 | 2006 |

| Halifax (county) | 359,183 | 372,858 |

|---|---|---|

| Cape Breton (county) | 109,330 | 105,928 |

| Kings County | 58,866 | 60,035 |

| Colchester County | 49,307 | 50,023 |

| Lunenburg County | 47,591 | 47,150 |

| Pictou County | 46,965 | 46,513 |

| Hants County | 40,513 | 41,182 |

| Cumberland County | 32,605 | 32,046 |

| Yarmouth County | 26,843 | 26,277 |

| Annapolis County | 21,773 | 21,438 |

Ethnic origins

According to the 2001 Canadian census[48] the largest ethnic group in Nova Scotia is Scottish (29.3%), followed by English (28.1%), Irish (19.9%), French (16.7%), German (10.0%), Dutch (3.9%), First Nations (3.2%), Welsh (1.4%), Italian (1.3%), and Acadian (1.2%). Peoples of European descent thus make up approximately 96.8% of the total population. Almost half of respondents (47.4%) identified their ethnicity as "Canadian".

Language

The 2006 Canadian census showed a population of 913,462.

Of the 899,270 singular responses to the census question concerning 'mother tongue' the most-commonly reported languages were:

| Rank | Language | Respondants | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | English | 833,105 | 92.53% |

| 2. | French | 32,540 | 3.62% |

| 3. | Arabic | 4,425 | 0.49% |

| 4. | Mi'kmaq | 4,060 | 0.45% |

| 5. | German | 4,045 | 0.45% |

| 6. | Chinese | 3,370 | 0.37% |

| 7. | Dutch | 2,440 | 0.27% |

| 8. | Polish | 1,570 | 0.17% |

| 9. | Spanish | 1,305 | 0.15% |

| 10. | Greek | 1,035 | 0.12% |

| 11. | Italian | 905 | 0.10% |

| 12. | Korean | 860 | 0.10% |

| 13. | Gaelic | 799 | 0.10% |

In addition, there were also 105 responses of both English and a 'non-official language'; 25 of both French and a 'non-official language'; 495 of both English and French; 10 of English, French, and a 'non-official language'; and about 10,300 people who either did not respond to the question, or reported multiple non-official languages, or else gave another unenumerated response. Figures shown are for the number of single language responses and the percentage of total single-language responses.[49]

Religion

The largest denominations by number of adherents according to the 2001 census were the Roman Catholic Church with 327,940 (37 %); the United Church of Canada with 142,520 (16 %); and the Anglican Church of Canada with 120,315 (13 %).[50]

Economy

Nova Scotia's traditionally resource-based economy has become more diverse in recent decades. The rise of Nova Scotia as a viable jurisdiction in North America was driven by the ready availability of natural resources, especially the fish stocks off the Scotian shelf. The fishery was pillar of the economy since its development as part of the economy of New France in the 17th century; however, the fishery suffered a sharp decline due to overfishing in the late twentieth century. The collapse of the cod stocks and the closure of this sector resulted in a loss of approximately 20,000 jobs in 1992.[51] Per capita GDP in 2005 was $31,344,[52] lower than the national average per capita GDP of $34,273 and less than half that of Canada's richest province, Alberta.

Due, in part, to a strong small-business sector, Nova Scotia now has one of the fastest-growing economies in Canada.[53] Mining, especially of gypsum and salt and to a lesser extent silica, peat and barite, is also a significant sector.[54] Since 1991, offshore oil and gas has become an increasingly important part of the economy. Agriculture remains an important sector in the province. In the central part of Nova Scotia, lumber and paper industries are responsible for much of the employment opportunities.

Nova Scotia’s defence and aerospace sector generates approximately $500 million in revenues and contributes about $1.5 billion to the provincial economy annually.[55] To date, 40% of Canada’s military assets reside in Nova Scotia.[56] Nova Scotia has the fourth-largest film industry in Canada hosting over 100 productions yearly, more than half of which are the products of international film and television producers.[57] Recently, the video game industry has grown with the emergence of developers such as HB Studios and Silverback Productions. The province made international headlines with an investment by Longtail Studios in 2009.[58]

The Nova Scotia tourism industry includes more than 6,500 direct businesses, supporting nearly 40,000 jobs.[59] 200,000 cruise ship passengers from around the world flow through the Port of Halifax, Nova Scotia each year.[60] This industry contributes approximately $1.3 billion annually to the economy.[61] The province also boasts a rapidly developing Information & Communication Technology (ICT) sector which consists of over 500 companies, and employs roughly 15,000 people.[62] The Life Sciences sector in the province is flourishing; some of the most innovative life sciences companies in the world can be found in Nova Scotia.[63] In 2006, the manufacturing sector brought in over $2.6 billion in chained GDP, the largest output of any industrial sector in Nova Scotia.[64] There are currently over 360 firms in the Insurance Industry of Nova Scotia; there is a forecasted 25% growth in employment for this industry in the province over the next three years.[65]

The average income of a Nova Scotian family is $47,100, ranking close to the national average; for Halifax, the average family income is $58,262, which far surpasses the national average.[citation needed] This, along with the province’s highly affordable real estate, makes Nova Scotia a cost-effective place to live.[66] Halifax ranks among the top five most cost-effective places to do business when compared to large international centres in North America, Europe and Asia-Pacific.[67]

Nova Scotia has a number of incentive programs, including tax refunds and credits that work to encourage small business growth.[68] The province is attracting major companies from all over the world that will help fuel the economy and provide jobs; companies like Research in Motion (RIM) and Lockheed Martin have seen the value of Nova Scotia and established branches in the province.[69]

Though only the second smallest province in Canada, Nova Scotia is a recognized exporter. The province is the world’s largest exporter of Christmas trees, lobster, gypsum, and wild berries.[70] Its export value of fish exceeds $1 billion, and fish products are received by 90 countries around the world.[71]

Government and politics

The government of Nova Scotia is a parliamentary democracy. Its unicameral legislature, the Nova Scotia House of Assembly, consists of fifty-two members. As Canada's head of state, Queen Elizabeth II is the head of Nova Scotia's Executive Council, which serves as the Cabinet of the provincial government. Her Majesty's duties in Nova Scotia are carried out by her representative, the Lieutenant-Governor, currently Mayann E. Francis. The government is headed by the Premier, Darrell Dexter, who took office June 19, 2009. Halifax is home to the House of Assembly and Government House, the residence of the Lieutenant-Governor.

The province's revenue comes mainly from the taxation of personal and corporate income, although taxes on tobacco and alcohol, its stake in the Atlantic Lottery Corporation, and oil and gas royalties are also significant. In 2006-07, the province passed a budget of $6.9 billion, with a projected $72 million surplus. Federal equalization payments account for $1.385 billion, or 20.07% of the provincial revenue. While Nova Scotians have enjoyed balanced budgets for years, the accumulated debt exceeds $12 billion (including forecasts of future liability, such as pensions and environmental cleanups), resulting in slightly over $897 million in debt servicing payments, or 12.67% of expenses.[72] The province participates in the HST, a blended sales tax collected by the federal government using the GST tax system.

Nova Scotia has elected three minority governments over the last decade. The Progressive Conservative government of John Hamm, and Rodney MacDonald, has required the support of the New Democratic Party or Liberal Party since the election in 2003. Nova Scotia's politics are divided on regional lines in such a way that it has become difficult to elect a majority government. Rural mainland Nova Scotia has largely been aligned behind the Progressive Conservative Party, Halifax Regional Municipality has overwhelmingly supported the New Democrats, with Cape Breton voting for Liberals with a few Progressive Conservatives and New Democrats. This has resulted in a three-way split of votes on a province-wide basis for each party and difficulty in any party gaining a majority.

The most recent election of June 9, 2009, elected 31 New Democrats, 11 Liberals and 10 Progressive Conservatives resulting in Nova Scotia's first New Democratic government, and first majority government in almost a decade.

Nova Scotia no longer has any incorporated cities; they were amalgamated into Regional Municipalities in 1996. Halifax, the provincial capital, is now part of the Halifax Regional Municipality, as is Dartmouth, formerly the province's second largest city. The former cities of Sydney and Glace Bay are now part of the Cape Breton Regional Municipality.

The House of Assembly passed a motion in 2004 inviting the Turks and Caicos Islands to join the province, should these Caribbean islands renew their wish to join Canada.

Education

The Minister of Education is responsible for the administration and delivery of education, as defined by the Education Act[73] and other acts relating to colleges, universities and private schools. The powers of the Minister and the Department of Education are defined by the Ministerial regulations and constrained by the Governor-In-Council regulations.

Nova Scotia has more than 450 public schools for children. The public system offers primary to Grade 12. There are also private schools in the province. Public education is administered by seven regional school boards, responsible primarily for English instruction and French immersion, and also province-wide by the Conseil Scolaire Acadien Provincial, which administer French instruction to students for whom the primary language is French.

The Nova Scotia Community College system has 13 campuses around the province. The community college, with its focus on training and education, was established in 1988 by amalgamating the province's former vocational schools.

In addition to its community college system the province has 11 universities, including Dalhousie University, University of King's College, Saint Mary's University (Halifax), Mount Saint Vincent University, NSCAD University, Acadia University, Université Sainte-Anne, Saint Francis Xavier University, Nova Scotia Agricultural College, Cape Breton University and the Atlantic School of Theology.

There are also more than 90 registered private commercial colleges in Nova Scotia.[74]

Culture

Despite the small population of the province, Nova Scotia's music and culture is influenced by well-established cultural groups, which are sometimes referred to as the "founding cultures".

The entire region comprising the present-day province was originally populated by the Mi'kmaq First Nation. The first European settlers were the French, who founded Acadia in 1604. Nova Scotia was briefly colonized by Scottish settlers in 1620, though by 1624 the Scottish settlers had been removed by treaty and the area was turned over to the French until the mid-18th century. After the defeat of the French and prior expulsion of the Acadians, settlers of English, Irish, Scottish and African descent began arriving on the shores of Nova Scotia.

Settlement was greatly accelerated by the resettlement of Loyalists in Nova Scotia during the period following the end of the American Revolutionary War. It was during this time that a large African Nova Scotian community took root, populated by freed slaves and Loyalist blacks and their families, who had fought for the crown in exchange for land. This community later grew when the Royal Navy began intercepting slave ships destined for the United States, and deposited these free slaves on the shores of Nova Scotia.

Later, in the 19th century the Irish Famine and, especially, the Scottish Highland Clearances resulted in large influxes of migrants with Celtic cultural roots, which helped to define the dominantly Celtic character of Cape Breton and the north mainland of the province. This Gaelic influence continues to play an important role in defining the cultural life of the province and around 500 to 2000 Nova Scotians today are fluent in Scottish Gaelic. Nearly all the population lives in halifax or on Cape Breton Island.[75][76]

Modern Nova Scotia is a mix of cultures. The government works to support Mi'kmaq, French, Gaelic and African-Nova Scotian culture through the establishment of government secretariats, as well as colleges, educational programs and cultural centres. The province is also eager to attract new immigrants,[77] but has had limited success. The major population centres at Halifax and Sydney are the most cosmopolitan, hosting large Arab populations (in the former) and Eastern European populations (in the latter). Halifax Regional Municipality hosts a yearly multicultural festival.[78]

Arts

Nova Scotia has long been a centre for artistic and cultural excellence. The city hosts such institutions such as Nova Scotia College of Art and Design University, and the Symphony Nova Scotia, the only full orchestra performing in Atlantic Canada. The province is home to avant-garde visual art and traditional crafting, writing and publishing and a film industry.

While popular music has experienced almost two decades of explosive growth and success in Nova Scotia, the province remains best known for its folk and traditional based music.[citation needed] Nova Scotia's traditional (or folk) music is Scottish in character, and traditions from Scotland are kept true to form, in some cases more so than in Scotland. This is especially true with Cape Breton Island, a major international centre for Celtic music.

See also

|

Lists:

- List of Nova Scotia rivers

- List of airports in Nova Scotia

- List of articles on Nova Scotia by topic

- List of renowned Nova Scotians

- List of Nova Scotia schools

- List of parks in Nova Scotia

- List of Nova Scotia counties

- List of communities in Nova Scotia

- List of colleges and universities in Nova Scotia

- List of Nova Scotia lieutenant-governors

- List of Nova Scotia premiers

- List of Nova Scotia provincial highways

- List of Canadian provincial and territorial symbols

Notes

- ^ "Gross domestic product, expenditure-based, by province and territory". 0.statcan.ca. 2009-11-10. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ Latin: Nova Scotia; English: New Scotland;Scottish Gaelic: Alba Nuadh

- ^ Statistics Canada. "Canada's population estimates 2009-12-23". Retrieved 2010-01-01.

- ^ the Nation of Mi'kma'ki also includes the Maritimes, parts of Maine, Newfoundland and the Gaspé Peninsula.

- ^ In 1765, the county of Sunbury was created, and included the territory of present-day New Brunswick and eastern Maine as far as the Penobscot River.

- ^ The other three provinces were New Brunswick and the Province of Canada (which became the separate provinces of Quebec and Ontario).

- ^ John Cabot - Giovanni Caboto - June 1497. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ^ Also, that same year, French fishermen established a settlement at Canso.

- ^ M. A. MacDonald, Fortune & La Tour: The civil war in Acadia, Toronto: Methuen. 1983

- ^ Brenda Dunn, p. 19

- ^ Brenda Dunn. A History of Port Royal, Annapolis Royal: 1605-1800. Nimbus Publishing, 2004. p. 20

- ^ Grenier, p. 56

- ^ Beamish Murdoch. History of Nova Scotia or Acadia, p. 399

- ^ A history of Nova-Scotia, or Acadie, Volume 1, by Beamish Murdoch, p. 398

- ^ The Nova Scotia theatre of the Dummer War is named the "Mi'kmaq-Maliseet War" by John Grenier. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia 1710-1760. University of Oklahoma Press. 2008.

- ^ Beamish Murdoch. A history of Nova-Scotia, or Acadie, Volume 1, p. 399; Geoffery Plank, An Unsettled Conquest, p. 78

- ^ Benjamin Church, p. 289; John Grenier, p. 62

- ^ Faragher, John Mack, A Great and Noble Scheme New York; W. W. Norton & Company, 2005. pp. 164-165; Brenda Dunn, p. 123

- ^ William Wicken. Mi'kmaq Treaties on Trial. 2002. pp. 72-72.

- ^ Grenier, John. The Far Reaches of Empire. War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 2008; Thomas Beamish Akins. History of Halifax, Brookhouse Press. 1895. (2002 edition). p 7

- ^ Wicken, p. 181; Griffith, p. 390; Also see http://www.northeastarch.com/vieux_logis.html

- ^ John Grenier. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Oklahoma University Press.

- ^ John Grenier. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Oklahoma University Press.

- ^ John Grenier, Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia 1710-1760. Oklahoma Press. 2008

- ^ Stephen E. Patterson. "Indian-White Relations in Nova Scotia, 1749-61: A Study in Political Interaction." Buckner, P, Campbell, G. and Frank, D. (eds). The Acadiensis Reader Vol 1: Atlantic Canada Before Confederation. 1998. pp.105-106.; Also see Stephen Patterson, Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples, p. 144.

- ^ Ronnie-Gilles LeBlanc (2005). Du Grand Dérangement à la Déportation: Nouvelles Perspectives Historiques, Moncton: Université de Moncton, 465 pages ISBN 1897214022 (book in French and English). The Acadians were scattered across the Atlantic, in the Thirteen Colonies, Louisiana, Quebec, Britain and France. (See Jean-François Mouhot (2009) Les Réfugiés acadiens en France (1758-1785): L'Impossible Réintégration?, Quebec, Septentrion, 456 p. ISBN 2894485131; Ernest Martin (1936) Les Exilés Acadiens en France et leur établissement dans le Poitou, Paris, Hachette, 1936). Very few eventually returned to Nova Scotia (See John Mack Faragher (2005). A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from their American Homeland, New York: W.W. Norton, 562 pages ISBN 0-393-05135-8 online excerpt).

- ^ Benjamin Franklin also engaged France in the war, which meant that many of the privateers were also from France.

- ^ Roger Marsters (2004). Bold Privateers: Terror, Plunder and Profit on Canada's Atlantic Coast" , p. 87-89.

- ^ Lieutenant Governor Sir Richard Hughes stated in a dispatch to Lord Germaine that "rebel cruisers" made the attack.

- ^ Thomas B. Akins. (1895) History of Halifax. Dartmouth: Brook House Press.p. 82

- ^ About a third of whom soon moved themselves to Sierra Leone in 1792 via the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor, becoming the Original settlers of Freetown. As well, Large numbers of Gaelic-speaking Highland Scots emigrated to Cape Breton and the western part of the mainland during the late 18th century and 19th century. In 1812 Sir Hector Maclean (the 7th Baronet of Morvern and 23rd Chief of the Clan Maclean) emigrated to Pictou from Glensanda and Kingairloch in Scotland with almost the entire population of 500. Sir Hector is buried in the cemetery at Pictou.

- ^ John Boileau. Half-hearted Enemies: Nova Scotia, New England and the War of 1812. Halifax: Formac Publishing. 2005. p.53

- ^ C.H.J.Snider, Under the Red Jack: privateers of the Maritime Provinces of Canada in the War of 1812 (London: Martin Hopkinson & Co. Ltd, 1928), 225-258 <http://www.1812privateers.org/Ca/canada.htm#LG>

- ^ Marquis, Greg. In Armageddon’s Shadow: The Civil War and Canada’s Maritime Provinces. McGill-Queen’s University Press. 1998.

- ^ Marquis, Greg. In Armageddon’s Shadow: The Civil War and Canada’s Maritime Provinces. McGill-Queen’s University Press. 1998.

- ^ Ted Harrison (1993). O Canada. Ticknor & Fields.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Environment Canada". Climate.weatheroffice.gc.ca. 2010-08-18. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ "Environment Canada". Climate.weatheroffice.gc.ca. 2010-08-18. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ "Environment Canada". Climate.weatheroffice.gc.ca. 2010-08-18. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ "Environment Canada". Climate.weatheroffice.gc.ca. 2010-08-18. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ "Environment Canada". Climate.weatheroffice.gc.ca. 2010-08-18. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ "Environment Canada". Climate.weatheroffice.gc.ca. 2010-08-18. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ "Environment Canada". Climate.weatheroffice.gc.ca. 2010-08-18. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ "Historical Weather for Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada". Weatherbase. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ "Historical Weather for Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada". Weatherbase. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ Environment Canada - Atlantic Climate Centre - The Climate of Nova Scotia[dead link]

- ^ "Statistics Canada — Population".. Retrieved December 8, 2009.

- ^ Statistics Canada (2005). "Population by selected ethnic origins, by province and territory (Census 2001)". Retrieved 2007-04-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Detailed Mother Tongue (186), Knowledge of Official Languages (5), Age Groups (17A) and Sex (3) (2006 Census)". 2.statcan.ca. 2010-05-19. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ "Religions in Canada". 2.statcan.ca. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ Fish in Crisis. "The Starving Ocean". Retrieved 2007-04-26.

- ^ Government of Nova Scotia (2007). "Economics and Statistics". Retrieved 2007-04-26.

- ^ Migrationnews Canada. 2007-2008 Edition. Oceania Development Group. Retrieved on: October 10, 2008.

- ^ Province of Nova Scotia, "Summary of Nova Scotia Mineral Production, 1994 and 1995"

- ^ Nova Scotia Business Inc. Defence, Security & Aerospace.Retrieved on: October 10, 2008.

- ^ Nova Scotia Business Inc. Defence, Security & Aerospace.Retrieved on: April 16, 2010.

- ^ Nova Scotia Film Development Corporation Production Statistics for the 12 Month Period Ended March 31, 2008. Retrieved on: October 10, 2008.

- ^ Leading-edge video game company comes to Nova Scotia [1]. Retrieved on: May 1, 2009.

- ^ Tourism Industry Association of Nova Scotia. Tourism Summit 2008. Retrieved on: October 10, 2008.

- ^ "Going Global, Staying Local: A Partnership Strategy for Export Development" (PDF). Government of Nova Scotia. Retrieved October 10, 2008.

- ^ Nova Scotia Business Inc. "Key Facts". Retrieved 2010-04-16.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) [dead link] - ^ Trade Team Nova Scotia. "Information and Communications Technology". Retrieved 2010-04-16. [dead link]

- ^ BioNova. "Nova Scotia Biotechnology" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ^ Invest In Canada. "Nova Scotia" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ^ Insureconomy. "Nova Scotia's Insurance Industry" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-04-16. [dead link]

- ^ Nova Scotia Business Inc. "Quality of Life". Retrieved 2010-04-16.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) [dead link] - ^ Carter, S. (ed.) Migrationnews Canada. 2007-2008 Edition. Oceania Development Group. Retrieved on: October 10, 2008.

- ^ Canada Business. "Tax Refunds and Credits". Retrieved 2010-04-16.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) [dead link] - ^ Nova Scotia Business Inc. "Locate Your Business in Nova Scotia". Retrieved 2010-04-16.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) [dead link] - ^ Tower Software. "The Nova Scotian Economy". Retrieved 2010-04-16. [dead link]

- ^ Trade Team Nova Scotia. "Fisheries & Aquaculture". Retrieved 2010-04-16. [dead link]

- ^ Government of Nova Scotia. "Nova Scotia estimates 2006-2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 10, 2006. Retrieved 2007-04-26.

- ^ Government of Nova Scotia (1996). "Education Act". Retrieved 2007-04-26.

- ^ "Registered Colleges for 2010-2011". Province of Nova Scotia. 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ Nova Scotia Archives (2006). "Gaelic Resources". Retrieved 2007-04-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Office of Gaelic Affairs". Gov.ns.ca. 2007-09-11. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ Nova Scotia Office of Immigration (2007). "Nova Scotia". Retrieved 2007-04-26.

- ^ "Nova Scotia Multicultural Festival". 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-26.

Bibliography

- Landry, Peter. The Lion & The Lily. Vol. 1, Trafford Publishing, Victoria, B.C., 2007. (ISBN 1425154506)

- Grenier, John. The Far Reaches of Empire. War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2008. (ISBN 9780806138763

- Murdoch, Beamish. History of Nova Scotia, Or Acadie. Vol 2. BiblioBazaar, LaVergne, TN, 1865.

- Thomas Akins. History of Halifax, Brookhouse Press. 1895. (2002 edition) (ISBN 1141698536)

- Brebner, John Bartlet. New England's Outpost. Acadia before the Conquest of Canada (1927)

- Brebner, John Bartlet. The Neutral Yankees of Nova Scotia: A Marginal Colony During the Revolutionary Years (1937)

- Griffiths, Naomi. E. S. From Migrant to Acadian, 1604-1755: A North American Border People. Montreal and Kingston, McGill / Queen's University Press, 2004.

- Pryke, Kenneth G. Nova Scotia and Confederation, 1864-74 (1979) (ISBN 0-8020-5389-0)

External links

- Official links

- Government of Nova Scotia

- Nova Scotia – Come To life (Main gateway website for tourism, immigration, business, etc. links)

- Tourism Nova Scotia

- Nova Scotia Provincial Parks

- Other links

- Nova Scotia at Curlie

- Coastal Communities Network current issues and community profiles, coastal information, community development

- Photographs of War Memorials & Historic Monuments in Nova Scotia

- Nova Scotia Archives