History of Germany: Difference between revisions

m Dated {{Citation needed}}. (Build p603) |

→World War I and revolution: rephrase re Kennedy |

||

| Line 252: | Line 252: | ||

Imperialist power politics and nationalism were the [[causes of World War I]], which started in August 1914. Germany stood behind its ally Austria in a confrontation with Serbia, and with Serbia's protector Russia, and with Russia's ally France. Germany fought on the side of Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire against Russia, France, Great Britain, Italy, Japan and several other smaller states, and against the United States starting in 1917. Fighting also spread to the Near East and the German colonies. |

Imperialist power politics and nationalism were the [[causes of World War I]], which started in August 1914. Germany stood behind its ally Austria in a confrontation with Serbia, and with Serbia's protector Russia, and with Russia's ally France. Germany fought on the side of Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire against Russia, France, Great Britain, Italy, Japan and several other smaller states, and against the United States starting in 1917. Fighting also spread to the Near East and the German colonies. |

||

===British security issues === |

|||

In explaining why neutral Britain went to war with Germany, Kennedy (1980) |

In explaining why neutral Britain went to war with Germany, Kennedy (1980) recognized it was critical for war that Germany become economically more powerful than Britain, but he downplays the disputes over economic trade imperialism, the [[Baghdad Railway]], confrontations in Eastern Europe, high-charged political rhetoric and domestic pressure-groups. Germany's reliance time and again on sheer power, while Britain increasingly appealed to moral sensibilities, played a role, especially in seeing the invasion of Belgium as a necessary military tactic or a profound moral crime. The German invasion of Belgium was not important because the British decision had already been made and the British were more concerned with the fate of France(pp 457-62). Kennedy argues that by far the main reason was London's fear that a repeat of 1870--when Prussia and the German states smashed France--would mean Germany, with a powerful army and navy, would control the English Channel, and northwest France. British policy makers insisted that would be a catastrophe for British security.<ref>Paul M. Kennedy, ''The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism, 1860-1914'' (1980) pp 464-70</ref> |

||

In the west, Germany sought a quick victory by encircling Paris using the [[Schlieffen Plan]]. But it failed due to Belgian resistance, Berlin's diversion of troops, and very stiff French resistance on the [[Marne]], north of Paris. The [[Western Front]] became an extremely bloody battleground until early 1918, with forces moving a few hundred yards at best. In the east there were decisive victories against the Russian army, the trapping and defeat of large parts of the Russian contingent at the [[Battle of Tannenberg]], followed by huge Austrian and German successes led to a breakdown of Russian forces and an imposed peace on the newly created USSR under Lenin. Churchill ordered a naval blockade in the [[North Sea]] which lasted until 1919, crippling Germany's supplies of raw materials and foodstuffs. The entry of the United States into the war in 1917 following Germany's declaration of ''unrestricted submarine warfare'' marked a decisive turning-point against Germany. |

In the west, Germany sought a quick victory by encircling Paris using the [[Schlieffen Plan]]. But it failed due to Belgian resistance, Berlin's diversion of troops, and very stiff French resistance on the [[Marne]], north of Paris. The [[Western Front]] became an extremely bloody battleground until early 1918, with forces moving a few hundred yards at best. In the east there were decisive victories against the Russian army, the trapping and defeat of large parts of the Russian contingent at the [[Battle of Tannenberg]], followed by huge Austrian and German successes led to a breakdown of Russian forces and an imposed peace on the newly created USSR under Lenin. Churchill ordered a naval blockade in the [[North Sea]] which lasted until 1919, crippling Germany's supplies of raw materials and foodstuffs. The entry of the United States into the war in 1917 following Germany's declaration of ''unrestricted submarine warfare'' marked a decisive turning-point against Germany. |

||

Revision as of 05:34, 10 January 2011

| History of Germany |

|---|

|

The concept of Germany as a distinct region in central Europe can be traced to Roman commander Julius Caesar, who referred to the unconquered area east of the Rhine as Germania, thus distinguishing it from Gaul (France), which he had conquered. Following the fall of the Roman Empire, the Franks conquered the other West Germanic tribes. When the Frankish Empire was divided among Charlemagne's heirs in 843, the eastern part became East Francia. Henry the Fowler became the first king of Germany in 919. In 962, Henry's son Otto I became the first emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, the medieval German state.

In the High Middle Ages, the dukes and princes of the empire gained power at the expense of the emperors. Martin Luther led the Protestant Reformation against the Catholic Church after 1517, as the northern states became Protestant, while the southern states remained Catholic. They clashed in the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), which was ruinous to the civilian population. 1648 marked the effective end of the Holy Roman Empire and the beginning of the modern nation-state system, with Germany divided into numerous independent states, such as Prussia, Bavaria and Saxony.

After the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), feudalism fell away and liberalism and nationalism clashed with reaction. The 1848 March Revolution failed. The Industrial Revolution modernized the German economy, led to the rapid growth of cities and to the emergence of the Socialist movement in Germany. Prussia, with its capital Berlin, grew in power. German universities became world-class centers for science and the humanities, while music and the arts flourished. Unification was achieved with the formation of the German Empire in 1871 under the leadership of Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. The Reichstag, an elected parliament, had only a limited role in the imperial government.

By 1900, Germany's economy matched Britain's, allowing colonial expansion and a naval race. Germany led the Central Powers in the First World War (1914-1918) against France, Great Britain, Russia and (by 1917) the United States. Defeated and partly occupied, Germany was forced to pay war reparations by the Treaty of Versailles and was stripped of its colonies as well as Polish areas and Alsace-Lorraine. The German Revolution of 1918–19 deposed the emperor and the kings, leading to the establishment of the Weimar Republic, an unstable parliamentary democracy.

In the early 1930s, the worldwide Great Depression hit Germany hard, as unemployment soared and people lost confidence in the government. In 1933, the Nazis under Adolf Hitler came to power and established a totalitarian regime. Political opponents were killed or imprisoned. Nazi Germany's aggressive foreign policy took control of Austria and parts of Czechoslovakia, and its invasion of Poland initiated the Second World War. After forming a pact with the Soviet Union in 1939, Hitler's blitzkrieg swept nearly all of Western Europe. In the Holocaust, the Jews in Germany and German-occupied areas were systematically killed. In 1941, however, the German invasion of the Soviet Union failed, and after the United States entered the war, Britain became the base for massive Anglo-American bombings of German cities. Following the Allied invasion of Normandy, the German army was pushed back on all fronts until the final collapse in May 1945.

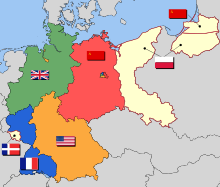

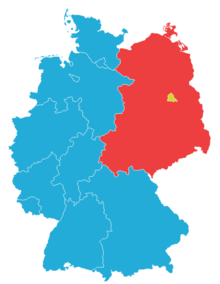

Under occupation by the Allies, German territories were split off, denazification took place, and the Cold War resulted in the division of the country into democratic West Germany and communist East Germany. Millions of ethnic Germans fled from Communist areas into West Germany, which experienced rapid economic expansion, and became the dominant economy in Western Europe. West Germany was rearmed in the 1950s under the auspices of NATO, but without access to nuclear weapons. The Franco-German friendship became the basis for the political integration of Western Europe in the European Union. In 1989, the Eastern bloc collapsed and East Germany was reunited with West Germany in 1990. The Deutsche Mark, which evolved into the leading European currency in the second half of the 20th century, was replaced by the Euro in 1999.

Pre-history

The earliest hominid fossils found in what is now Germany are Homo heidelbergensis (500,000 years old) and the Steinheim Skull (300,000 years old). The Neanderthals, named for Neander Valley, flourished around 100,000 years ago. The region was glaciated from 30,000 years ago to about 10,000 years ago. The Nebra sky disk, dated 1600 BC, is one of the oldest known astronomical instruments found anywhere. Northern Germany experienced the Nordic Bronze Age from 1700BC to 450BC and thereafter the Pre-Roman Iron Age. Differences between artifacts from northern Germany and those from southern Germany suggest the beginning of differentiation between the Germanic and Celtic peoples. In the 1st century BC, the Germanic tribes began expanding south, east, and west.[1]

Early history (56 BC to 260 AD)

Germany entered recorded history in June 56 BC, when Roman commander Julius Caesar crossed the Rhine. His army built a huge wooden bridge in only ten days. He retreated back to Gaul upon learning that the Suevi tribe was gathering to oppose him. The English word "Germany" is derived from the Latin Germania, a word first recorded in Caesar's writings.[2]

Under Augustus, the Roman General Publius Quinctilius Varus began to invade Germania (to the Romans, an area running roughly from the Rhine to the Ural Mountains), and it was in this period that the Germanic tribes became familiar with Roman tactics of warfare while maintaining their tribal identity. In AD 9, three Roman legions led by Varus were defeated by the Cheruscan leader Arminius in the clades Variana ("Battle of the Teutoburg Forest"). Arminius later suffered a defeat at the hands of the Roman general Germanicus at the Battle of the Weser River or Idistaviso in AD 16, but the Roman victory was not followed up after the Roman Emperor Tiberius recalled Germanicus to Rome in AD 17. Tiberius wished that the Roman frontier with Germania be maintained along the Rhine. Modern Germany, as far as the Rhine and the Danube, thus remained outside the Roman Empire. By AD 100, the time of Tacitus' Germania, Germanic tribes settled along the Rhine and the Danube (the Limes Germanicus), occupying most of the area of modern Germany. The 3rd century saw the emergence of a number of large West Germanic tribes: Alamanni, Franks, Chatti, Saxons, Frisians, Sicambri, and Thuringii. Around 260, the Germanic peoples broke through the Limes and the Danube frontier into Roman-controlled lands.[3]

Germania

Six great German tribes, the Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Vandals, Burgundians, Lombards and the Franks took part in the fragmentation and the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. The vandals were two tribes, Hasdingi and the Silingi. Several other tribes were also involved in the the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the Alans and the Suebi in particular, but the Alans were an Iranian people, not Germans. The six major tribes found major kingdoms. All of them disappeared with one exception, the Franks.

Besides the German tribes which attacked the Western Roman Empire, there were the tribes that stayed back in Germany proper, notably the Saxons, Alemanni, and the Thuringian Rugier. All of these elements were finally subdued by the Franks, the Alamanni in 496 and 505, the Thuringia in 531, the Bavarians after a certain point 553, and finally the Saxons of 804.

The Stem Duchies & Marches

The Stem Duchies (tribal duchies) in Germany was mainly the areas of the old German tribes of the region. These strains were originally the Franks, the Saxons, the Alemanni, the Burgundians, the Thuringians, and the Rugians. In the 5th Century the Burgundians moved into Roman territory and would have been in 443 and 458 in the area, then Lower Burgundy. The area they had occupied in Germany, along with the Saxons, was occupied by the Franks. The Rugians which Odoacer destroyed in 487 formed a new confederation of Germans in their place, the Bavarians. All of these strains in Germany were finally subdued by the Franks, the Alamanni in 496 and 505, the Thuringia in 531, the Bavarians after a certain point 553, and then the Saxons, in a lengthy campaign of Charles himself, from 804. When Germany finally separated as the East Francia, took over the tribal areas of new identities as the subdivisions of the Empire, joining Lorraine (right Francia Media). For the ruler of this ancient Roman title dux ("the leader") was adopted. It was originally a term used to denote a Roman frontier military commander. In German, however, the corresponding title, Herzog, more like a translation of a Greek, , stratêlatês, "army" (stratos) "leader" (elaunein, "to lead"). Thus, the Old High German title of herizoho, from heri, "army," and ziohan, "to lead." This looks very much like a similar title, voivode, maybe a translation into Slavic languages.

The Franks

The Merovingian kings of the Germanic Franks conquered northern Gaul in 486 AD. In the 5th and 6th centuries the Merovingian kings conquered several other Germanic tribes and kingdoms and placed them under the control of autonomous dukes of mixed Frankish and native blood. Frankish Colonists were encouraged to move to the newly conquered territories. While the local Germanic tribes were allowed to preserve their laws, they were pressured into changing their religion.

Frankish Empire

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire the Franks created an empire under the Merovingian kings and subjugated the other Germanic tribes. Swabia became a duchy under the Frankish Empire in 496, following the Battle of Tolbiac. Already king Chlothar I ruled the greater part of what is now Germany and made expeditions into Saxony while the Southeast of modern Germany was still under influence of the Ostrogoths. In 531 Saxons and Franks destroyed the Kingdom of Thuringia. Saxons inhabit the area down to the Unstrut river. During the partition of the Frankish empire their German territories were a part of Austrasia. In 718 the Franconian Mayor of the Palace Charles Martel made war against Saxony, because of its help for the Neustrians. The Franconian Carloman started in 743 a new war against Saxony, because the Saxons gave aid to Duke Odilo of Bavaria. In 751 Pippin III, mayor of the palace under the Merovingian king, himself assumed the title of king and was anointed by the Church. The Frankish kings now set up as protectors of the Pope, Charlemagne launched a decades-long military campaign against their heathen rivals, the Saxons and the Avars. The Saxons (by the Saxon Wars (772-804)) and Avars were eventually overwhelmed and forcibly converted, and their lands were annexed by the Carolingian Empire.

Middle Ages

In 768 the Frankish king died, leaving his kingdom to his two sons—Charles and Carloman.[4] When Carloman suddenly died in 771, Charles seized his brother's lands and made them part of his own kingdom. During the next two years, Charles consolidated his control over his kingdom and became more commonly known as "Charles the Great" or "Charlemagne." From 771 until his death in 814, Charlemagne extended the Carolingian empire into northern Italy and the territories of all west Germanic peoples, including the Saxons and the Bajuwari (Bavarians). In 800, Charlemagne's authority was confirmed by his coronation as emperor in Rome. The Frankish empire was divided into counties, and its frontiers were protected by border marches. Imperial strongholds (Kaiserpfalzen) became economic and cultural centres (Aachen being the most famous[5]).

Between 843 and 880, after fighting between Charlemagne's grandchildren, the Carolingian empire was partitioned into several parts in the Treaty of Verdun (843), the Treaty of Meerssen (870) and the Treaty of Ribemont[6] The German region developed out of the East Frankish kingdom, East Francia. From 919 to 936 the Germanic peoples (Franks, Saxons, Swabians and Bavarians) were united under Duke Henry of Saxony, who took the title of king. For the first time, the term Kingdom (Empire) of the Germans ("Regnum Teutonicorum") was applied to a Frankish kingdom, even though Teutonicorum at its founding originally meant something closer to "Realm of the Germanic peoples" or "Germanic Realm" than realm of the Germans.[7]

Otto the Great

In 936 , Otto I the Great was crowned at Aachen. He strengthened the royal authority by re-asserting the old Carolingian rights over ecclesiastical appointments.[8] Otto wrested from the nobles the powers of appointment of the bishops and abbots, who controlled large land holdings. Additionally, Otto revived the old Carolingian program of appointing missionaries in the border lands. Otto continued to support the celibacy rule for the higher clergy. Thus, the ecclesiastical appointments never became hereditary. By granting land to the abbotts and bishops he appointed, Otto actually made these bishops into "princes of the Empire" (Reichsfürsten).[9] In this way, Otto was able to establish a national church. In 951 Otto the Great married the widowed Queen Adelheid, thereby winning the Lombard crown. Outside threats to the kingdom were contained with the decisive defeat of the Magyars of Hungary near Augsburg at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955. The Slavs between the Elbe and the Oder rivers were also subjugated. Otto marched on Rome and drove John XII from the papal throne and for years controlled the election of the pope, setting a firm precedent for imperial control of the papacy for years to come. In 962, Otto I was crowned emperor in Rome, taking the succession of Charlemagne, and this also helped establish a strong Frankish influence over the Papacy.

During the reign of Conrad II's son, Henry III (1039 to 1056 ), the Holy Roman Empire supported the Cluniac reform of the Church - the Peace of God, the prohibition of simony (the purchase of clerical offices) and the celibacy of priests. Imperial authority over the Pope reached its peak. In the Investiture Controversy which began between Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII over appointments to ecclesiastical offices, the emperor was compelled to submit to the Pope at Canossa in 1077, after having been excommunicated. In 1122 a temporary reconciliation was reached between Henry V and the Pope with the Concordat of Worms. The consequences of the investiture dispute were a weakening of the Ottonian church (Reichskirche), and a strengthening of the Imperial secular princes.[10]

The time between 1096 and 1291 was the age of the crusades. Knightly religious orders were established, including the Templars, the Knights of St John and the Teutonic Order[11] .

Towns

From 1100, new towns were founded around imperial strongholds, castles, bishops' palaces and monasteries. The towns began to establish municipal rights and liberties (see German town law), while the rural population remained in a state of serfdom. In particular, several cities became Imperial Free Cities, which did not depend on princes or bishops, but were immediately subject to the Emperor. The towns were ruled by patricians (merchants carrying on long-distance trade). The craftsmen formed guilds, governed by strict rules, which sought to obtain control of the towns. Trade with the East and North intensified, as the major trading towns came together in the Hanseatic League, under the leadership of Lübeck.[12]

Wars and expansion

The German colonisation and the chartering of new towns and villages began into largely Slav-inhabited territories east of the Elbe, such as Bohemia, Silesia, Pomerania, and Livonia (see also Ostsiedlung).[13]

Henry V, great-grandson of Conrad II became Holy Roman Emperor in 1106 upon the death of his father, Henry IV. Henry V's reign was born into a civil war which had continued from his fathers' reign.[14] Hoping to gain complete control over the church inside the Empire, Henry V appointed Adalbert of Saarbruken as archbishop of Mainz in 1111 However, like Becket in England some fifty years later, once appointed as archbishop, Adalbert began to take his position seriously and began to assert the powers of the Church against secular authorities, that is, the Emperor. This precipitated the "Crisis of 1111". Henry, Duke of Bavaria, known as Henry the Proud, became heir to the duchy of Saxony, making him the most powerful lord in the kingdom, as well as the logical successor of Lothair as the Holy Roman Emperor. However in 1137 the magnates turned back to the Hohenstaufen family for a candidate, Conrad III. Conrad III tried to Henry the Proud of his two duchies, leading to war in southern Germany as the Empire divided into two factions. The first faction called themselves the "Welfs" after Henry the Proud's family name which was the ruling dynasty in Bavaria. The other faction was known as the "Waiblings." In this early period, the Welfs generally represented ecclesiastical independence under the papacy plus "particularism" (a strengthening of the local duchies against the central imperial authority). The Waiblings on the other hand stood for control of the Church by a strong central Imperial government.[15]

Between 1152 and 1190, during the reign of Frederick I (Barbarossa), of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, an accommodation was reached with the rival Guelph party by the grant of the duchy of Bavaria to Henry the Lion, duke of Saxony. Austria became a separate duchy by virtue of the Privilegium Minus in 1156.[16] Barbarossa tried to reassert his control over Italy. In 1177 a final reconciliation was reached between the emperor and the Pope in Venice.

In 1180 Henry the Lion was outlawed and Bavaria was given to Otto of Wittelsbach (founder of the Wittelsbach dynasty which was to rule Bavaria until 1918), while Saxony was divided.

From 1184 to 1186 the Hohenstaufen empire under Barbarossa reached its peak in the Reichsfest (imperial celebrations) held at Mainz and the marriage of his son Henry in Milan to the Norman princess Constance of Sicily. The power of the feudal lords was undermined by the appointment of "ministerials" (unfree servants of the Emperor) as officials. Chivalry and the court life flowered, leading to a development of German culture and literature (see Wolfram von Eschenbach).

Between 1212 and 1250 Frederick II established a modern, professionally administered state in Sicily. He resumed the conquest of Italy, leading to further conflict with the Papacy. In the Empire, extensive sovereign powers were granted to ecclesiastical and secular princes, leading to the rise of independent territorial states. The struggle with the Pope sapped the Empire's strength, as Frederick II was excommunicated three times. After his death, the Hohenstaufen dynasty fell, followed by an interregnum during which there was no Emperor.

Beginning in 1226 under the auspices of Emperor Frederick II, the Teutonic Knights began their conquest of Prussia after being invited to Chelmno Land by the Polish Duke Konrad I of Masovia. The native Baltic Prussians were conquered and Christianized by the Knights with much warfare, and numerous German towns were established along the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. From 1300, however, the Empire started to lose territory on all its frontiers.

The failure of negotiations between Emperor Louis IV with the papacy led in 1338 to the declaration at Rhense by six electors to the effect that election by all or the majority of the electors automatically conferred the royal title and rule over the empire, without papal confirmation.

Between 1346 and 1378 Emperor Charles IV of Luxembourg, king of Bohemia, sought to restore the imperial authority.

Around 1350 Germany and almost the whole of Europe were ravaged by the Black Death. Jews were persecuted on religious and economic grounds; many fled to Poland.

The Golden Bull of 1356 stipulated that in future the emperor was to be chosen by four secular electors (the King of Bohemia, the Count Palatine of the Rhine, the Duke of Saxony, and the Margrave of Brandenburg) and three spiritual electors (the Archbishops of Mainz, Trier, and Cologne).

After the disasters of the 14th century, early-modern European society gradually came into being as a result of economic, religious and political changes. A money economy arose which provoked social discontent among knights and peasants. Gradually, a proto-capitalistic system evolved out of feudalism. The Fugger family gained prominence through commercial and financial activities and became financiers to both ecclesiastical and secular rulers.

The knightly classes found their monopoly on arms and military skill undermined by the introduction of mercenary armies and foot soldiers. Predatory activity by "robber knights" became common. From 1438 the Habsburgs, who controlled most of the southeast of the Empire (more or less modern-day Austria and Slovenia, and Bohemia and Moravia after the death of King Louis II in 1526), maintained a constant grip on the position of the Holy Roman Emperor until 1806 (with the exception of the years between 1742 and 1745). This situation, however, gave rise to increased disunity among the Holy Roman Empires territorial rulers and prevented sections of the country from coming together and forming nations in the manner of France and England.

During his reign from 1493 to 1519, Maximilian I tried to reform the Empire: an Imperial supreme court (Reichskammergericht) was established, imperial taxes were levied, the power of the Imperial Diet (Reichstag) was increased. The reforms were, however, frustrated by the continued territorial fragmentation of the Empire.

Early modern Germany

| Part of a series on |

| Lutheranism |

|---|

|

- see List of states in the Holy Roman Empire for subdivisions and the political structure

Reformation and Thirty Years War

Around the beginning of the 16th century there was much discontent in the Holy Roman Empire caused by abuses such as indulgences in the Catholic Church and a general desire for reform.

In 1515 the Frisian peasants rebellion took place. Led by Pier Gerlofs Donia and Wijard Jelckama, thousands of Frisians (a Germanic race) fought against the suppression of their lands by Charles V. The hostilities ended in 1523 when the remaining leaders were captured and decapitated.

In 1517 the Reformation began with the publication of Martin Luther's 95 Theses; he had posted them in the town square, and gave copies of them to German nobles, but it is debated whether he nailed them to the church door in Wittenberg as is commonly said. The list detailed 95 assertions Luther believed to show corruption and misguidance within the Catholic Church. One often cited example, though perhaps not Luther's chief concern, is a condemnation of the selling of indulgences; another prominent point within the 95 Theses is Luther's disagreement both with the way in which the higher clergy, especially the pope, used and abused power, and with the very idea of the pope.

In 1521 Luther was outlawed at the Diet of Worms. But the Reformation spread rapidly, helped by the Emperor Charles V's wars with France and the Turks. Hiding in the Wartburg Castle, Luther translated the Bible from Latin to German, establishing the basis of the German language. A curious fact is that Luther spoke a dialect which had minor importance in the German language of that time. After the publication of his Bible, his dialect suppressed the others and evolved into what is now the modern German.

In 1524 the German Peasants' War broke out in Swabia, Franconia and Thuringia against ruling princes and lords, following the preachings of Reformist priests. But the revolts, which were assisted by war-experienced noblemen like Götz von Berlichingen and Florian Geyer (in Franconia), and by the theologian Thomas Münzer (in Thuringia), were soon repressed by the territorial princes. It is estimated that as many as 100,000 German peasants were massacred during the revolt,[17] usually after the battles had ended.[18] With the protestation of the Lutheran princes at the Reichstag of Speyer (1529) and rejection of the Lutheran "Augsburg Confession" at Augsburg (1530), a separate Lutheran church emerged.

From 1545 the Counter-Reformation began in Germany. The main force was provided by the Jesuit order, founded by the Spaniard Ignatius of Loyola. Central and northeastern Germany were by this time almost wholly Protestant, whereas western and southern Germany remained predominantly Catholic. In 1547, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V defeated the Schmalkaldic League, an alliance of Protestant rulers.

The Peace of Augsburg in 1555 brought recognition of the Lutheran faith. But the treaty also stipulated that the religion of a state was to be that of its ruler (Cuius regio, eius religio).

In 1556 Charles V abdicated. The Habsburg Empire was divided, as Spain was separated from the Imperial possessions.

In 1608/1609 the Protestant Union and the Catholic League were formed.

From 1618 to 1648 the Thirty Years' War ravaged in the Holy Roman Empire. The causes were the conflicts between Catholics and Protestants, the efforts by the various states within the Empire to increase their power and the Emperor's attempt to achieve the religious and political unity of the Empire. The immediate occasion for the war was the uprising of the Protestant nobility of Bohemia against the emperor (Defenestration of Prague), but the conflict was widened into a European War by the intervention of King Christian IV of Denmark (1625–29), Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden (1630–48) and France under Cardinal Richelieu, the regent of the young Louis XIV (1635–48). Germany became the main theatre of war and the scene of the final conflict between France and the Habsburgs for predominance in Europe. The war resulted in large areas of Germany being laid waste, a loss of approximately a third of its population, and in a general impoverishment.

The war ended in 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia, signed in Münster and Osnabrück: Imperial territory was lost to France and Sweden and the Netherlands left the Holy Roman Empire after being de facto seceded for 80 years already. The imperial power declined further as the states' rights were increased.

End of the Holy Roman Empire

From 1640, Brandenburg-Prussia had started to rise under the Great Elector, Frederick William. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 strengthened it even further, through the acquisition of East Pomerania. A system of rule based on absolutism was established.

In 1701 Elector Frederick of Brandenburg was crowned "King in Prussia". From 1713 to 1740, King Frederick William I, also known as the "Soldier King", established a highly centralised state.

Meanwhile Louis XIV of France had conquered parts of Alsace and Lorraine (1678–1681), and had invaded and devastated the Palatinate (1688–1697) in the War of Palatinian Succession. Louis XIV benefited from the Empire's problems with the Turks, which were menacing Austria. Louis XIV ultimately had to relinquish the Palatinate.

In 1683 the Ottoman Turks were defeated outside Vienna by a Polish relief army led by King Jan Sobieski of Poland while the city itself was defended by Imperial and Austrian troops under the command of Charles IV, Duke of Lorraine, accompanied by Prince Eugene of Savoy and elector Maximilian Emanuel of Bavaria, the "liberator of Belgrade". Hungary was reconquered, and later became a new destination for German settlers. Austria, under the Habsburgs, developed into a great power.

In the War of Austrian Succession (1740–1748) Maria Theresa fought successfully for recognition of her succession to the throne. But in the Silesian Wars and in the Seven Years' War she had to cede Silesia to Frederick II, the Great, of Prussia. After the Peace of Hubertsburg in 1763 between Austria, Prussia and Saxony, Prussia became a European great power. This gave the start to the rivalry between Prussia and Austria for the leadership of Germany.

From 1763, against resistance from the nobility and citizenry, an "enlightened absolutism" was established in Prussia and Austria, according to which the ruler was to be "the first servant of the state". The economy developed and legal reforms were undertaken, including the abolition of torture and the improvement in the status of Jews; the emancipation of the peasants slowly began. Education began to be enforced under threat of compulsion.

In 1772-1795 Prussia took part in the partitions of Poland, occupying western territories of Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth, which led to centuries of Polish resistance against German rule and persecution.

The French Revolution began in 1789. In 1792, Prussia and Austria were the first countries to declare war on France. By 1795, the French had overrun the Austrian Netherlands and the left bank of the Rhine and Prussia had dropped out of the war. Austria continued to fight until 1797 when it was defeated by Napoleon Bonaparte in Italy and signed the Treaty of Campo Formio, whereby it gave up Milan and recognised the loss of the Austrian Netherlands and the left bank of the Rhine, but gained Venice.

In 1799, hostilities with France resumed in the War of the Second Coalition. The conflict terminated with the Peace of Luneville in 1801. In 1803, under the "Reichsdeputationshauptschluss" (a resolution of a committee of the Imperial Diet meeting in Regensburg), Napoleon abolished almost all the ecclesiastical and the smaller secular states and most of the imperial free cities. New medium-sized states were established in southwestern Germany. In turn, Prussia gained territory in northwestern Germany.

In 1805, the War of the Third Coalition began. The main Austrian army under general Karl Mack was trapped at Ulm by Napoleon and forced to capitulate. The French then occupied Vienna, and routed a combined Austrian and Russian army at Austerlitz in December 1805. Afterwards, Austria ceded Venice and the Tirol to France and recognised the independence of Bavaria.

The Holy Roman Empire was formally dissolved on 6 August 1806 when the last Holy Roman Emperor Francis II (from 1804, Emperor Francis I of Austria) resigned. Francis II's family continued to be called Austrian emperors until 1918. In 1806, the Confederation of the Rhine was established under Napoleon's protection, which comprised all the minor states of Germany.

Prussia now felt threatened by the large concentration of French troops in Germany and demanded their withdrawal. When France refused, Prussia declared war. The result was a disaster. The Prussian armies were routed at Auerstedt and Jena. The French occupied Berlin and crossed east into Poland. When the Treaty of Tilsit terminated the war, Prussia had lost 40% of its territory, including its recently acquired section of Poland, and had to reduce its army to 45,000 men. There was no popular uprising against the French invasion, and the Prussian populace in fact showed complete apathy.

From 1808 to 1812 Prussia was reconstructed, and a series of reforms were enacted by Freiherr vom Stein and Freiherr von Hardenberg, including the regulation of municipal government, the liberation of the peasants and the emancipation of the Jews. These reforms were designed to encourage the spirit of nationalism in the people and give them something worth fighting for. A reform of the army was undertaken by the Prussian generals Gerhard von Scharnhorst and August von Gneisenau. The army was brought out of the 18th century. Mercenary troops were discarded, and discipline made more humane. Soldiers were encouraged to fight for their country and not merely because a commanding officer told them to.

In 1813 the Wars of Liberation began, following the destruction of Napoleon's army in Russia (1812). After the Battle of the Nations at Leipzig, Germany was liberated from French rule. The Confederation of the Rhine was dissolved.

In 1815 Napoleon was finally defeated at Waterloo by the Britain's Duke of Wellington and by Prussia's Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher. Prussia was considerably expanded after the war, gaining a large part of western Germany, including much of the Rhineland. In the east, it absorbed most of Saxony and also got back some of the Polish territory that had been lost in 1806, although the central part of Poland was left under Russian control.

German Confederation

Restoration and Revolution

After the fall of Napoleon, European monarchs and statesmen convened in Vienna in 1815 for the reorganisation of European affairs, under the leadership of the Austrian Prince Metternich. The political principles agreed upon at this Congress of Vienna included the restoration, legitimacy and solidarity of rulers for the repression of revolutionary and nationalist ideas.

On the territory of the former "Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation", the German Confederation (Deutscher Bund) was founded, a loose union of 39 states (35 ruling princes and 4 free cities) under Austrian leadership, with a Federal Diet (Bundestag) meeting in Frankfurt am Main. While this was a great improvement over the 300+ political entities that comprised the old Holy Roman Empire, it was still not satisfactory to many nationalists, and within a few decades, the advent of industrialisation made the German Confederation unworkable. Moreover, not everyone was satisfied with Austria's leading role in the Confederation. Some argued that it made sense as Austria had been the most powerful German state for more than 400 years, but others said that it was too much of a polyglot nation to be acceptable for such a role, and that Prussia was the natural leader of Germany.

In 1817, inspired by liberal and patriotic ideas of a united Germany, student organisations gathered for the "Wartburg festival" at Wartburg Castle, at Eisenach in Thuringia, on the occasion of which reactionary books were burnt.

In 1819 the student Karl Ludwig Sand murdered the writer August von Kotzebue, who had scoffed at liberal student organisations. Prince Metternich used the killing as an occasion to call a conference in Karlsbad, which Prussia, Austria and eight other states attended, and which issued the Karlsbad Decrees: censorship was introduced, and universities were put under supervision. The decrees also gave the start to the so-called "persecution of the demagogues", which was directed against individuals who were accused of spreading revolutionary and nationalist ideas. Among the persecuted were the poet Ernst Moritz Arndt, the publisher Johann Joseph Görres and the "Father of Gymnastics" Ludwig Jahn.

In 1834 the Zollverein was established, a customs union between Prussia and most other German states, but excluding Austria. As industrialisation developed, the need for a unified German state with a uniform currency, legal system, and government became more and more obvious.

Growing discontent with the political and social order imposed by the Congress of Vienna led to the outbreak, in 1848, of the March Revolution in the German states. In May the German National Assembly (the Frankfurt Parliament) met in St. Paul's Church in Frankfurt to draw up a national German constitution.

But the 1848 revolution turned out to be unsuccessful: King Frederick William IV of Prussia refused the imperial crown, the Frankfurt parliament was dissolved, the ruling princes repressed the risings by military force and the German Confederation was re-established by 1850.

The 1850s were a period of extreme political reaction. Dissent was vigorously suppressed, and many Germans emigrated to America following the collapse of the 1848 uprisings. Frederick William IV became extremely depressed and melancholy during this period, and was surrounded by men who advocated clericalism and absolute divine monarchy. The Prussian people once again lost interest in politics. In 1857, the king had a stroke and remained incapacitated until his death in 1861. His brother William succeeded him. Although conservative, he was far more pragmatic and rejected the superstitions and mysticism of Frederick.

William I's most significant accomplishment as king was the nomination of Otto von Bismarck as chancellor in 1862. The combination of Bismarck, Defense Minister Albrecht von Roon, and Field Marshal Helmut von Moltke set the stage for the unification of Germany.

In 1863-64, disputes between Prussia and Denmark grew over Schleswig, which - unlike Holstein - was not part of the German Confederation, and which Danish nationalists wanted to incorporate into the Danish kingdom. The dispute led to the Second War of Schleswig, which lasted from February–October 1864. Prussia, joined by Austria, defeated Denmark easily and occupied Jutland. The Danes were forced to cede both the duchy of Schleswig and the duchy of Holstein to Austria and Prussia. In the aftermath, the management of the two duchies caused growing tensions between Austria and Prussia. The former wanted the duchies to become an independent entity within the German Confederation, while the latter wanted to annex them. The Seven Weeks War broke out in June 1866. There was widespread opposition to the war in Prussia, as few believed that Austria could be defeated. On 3 July, the two armies clashed at Sadowa-Koniggratz in Bohemia in an enormous battle involving half a million men. The Prussian breech-loading needle guns carried the day over the Austrians with their slow muzzle-loading rifles, who lost a quarter of their army in the battle. Austria ceded Venice to Italy, but did not lose any other territory and had to only pay a modest war indemnity. The defeat came as a great shock to the rest of Europe, especially France, whose leader Napoleon III had hoped the two countries would exhaust themselves in a long war, after which France would step in and help itself to pieces of German territory. Now the French faced an increasingly strong Prussia.

North German Federation

In 1866, the German Confederation was dissolved. In its place the North German Federation (German Norddeutscher Bund) was established, under the leadership of Prussia. Austria was excluded from it. The Austrian hegemony in Germany that had begun in the 15th century finally came to an end.

The North German Federation was a transitional organisation that existed from 1867 to 1871, between the dissolution of the German Confederation and the founding of the German Empire. The unification of the German states into a single economic, political and administrative unit excluded the Austrian territories and the Habsburgs.

Railways

Political disunity of three dozen states and a pervasive conservatism made it difficult to build railways in the 1830s. However, by the 1840s, trunk lines did link the major cities; each German state was responsible for the lines within its own borders. Economist Friedrich List summed up the advantages to be derived from the development of the railway system in 1841:

- 1/ as a means of national defence, it facilitates the concentration, distribution and direction of the army.

2/ It is a means to the improvement of the culture of the nation…. It brings talent, knowledge and skill of every kind readily to market.

3/ It secures the community against dearth and famine, and against excessive fluctuation in the prices of the necessaries of life.

4/ It promotes the spirit of the nation, as it has a tendency to destroy the Philistine spirit arising from isolation and provincial prejudice and vanity. It binds nations by ligaments, and promotes an interchange of food and of commodities, thus making it feel to be a unit. The iron rails become a nerve system, which, on the one hand, strengthens public opinion, and, on the other hand, strengthens the power of the state for police and governmental purposes.[19]

Lacking a technological base at first, the Germans imported their engineering and hardware from Britain, but quickly learned the skills needed to operate and expand the railways. In many cities, the new railway shops were the centres of technological awareness and training, so that by 1850, Germany was self sufficient in meeting the demands of railroad construction, and the railways were a major impetus for the growth of the new steel industry. Observers found that even as late as 1890, their engineering was inferior to Britain’s. However, German unification in 1870 stimulated consolidation, nationalisation into state-owned companies, and further rapid growth. Unlike the situation in France, the goal was support of industrialisation, and so heavy lines crisscrossed the Ruhr and other industrial districts, and provided good connections to the major ports of Hamburg and Bremen. By 1880, Germany had 9,400 locomotives pulling 43,000 passengers and 30,000 tons of freight, and forged ahead of France[20]

German Empire

After Germany was united by Bismarck into the Second German Reich, Bismarck determined German politics until 1890. Bismarck tried to foster alliances in Europe, on one hand to contain France, and on the other hand to consolidate Germany's influence in Europe. On the domestic front Bismarck tried to stem the rise of socialism by anti-socialist laws, combined with an introduction of health care and social security. At the same time Bismarck tried to reduce the political influence of the emancipated Catholic minority in the Kulturkampf, literally "culture struggle". The Catholics only grew stronger, forming the Center (Zentrum) Party. Germany grew rapidly in industrial and economic power, matching Britain by 1900. Its highly professional army was the best in the world, but the navy could never catch up with Britain's Royal Navy.

In 1888, the young and ambitious Kaiser Wilhelm II became emperor. He could not abide advice, least of all from the most experienced politician and diplomat in Europe, so he fired Bismarck. The Kaiser opposed Bismarck's careful foreign policy and wanted Germany to pursue colonialist policies, as Britain and France had been doing for decades, as well as build a navy that could match the British. The Kaiser promoted active colonization of Africa and Asia for those areas that were not already colonies of other European powers; his record was notoriously brutal and set the stage for genocide. The Kaiser took a mostly unilateral approach in Europe with as main ally the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and an arms race with Britain, which eventually led to the situation in which the assassination of the Austrian-Hungarian crown price could spark off World War I.

Age of Bismarck

Disputes between France and Prussia increased. In 1868, the Spanish queen Isabella II was expelled by a revolution, leaving that country's throne vacant. When Prussia tried to put a Hohenzollern candidate, Prince Leopold, on the Spanish throne, the French angrily protested. In July 1870, France declared war on Prussia (the Franco-Prussian War). The debacle was swift. A succession of German victories in northeastern France followed, and one French army was besieged at Metz. After a few weeks, the main army was finally forced to capitulate in the fortress of Sedan. French Emperor Napoleon III was taken prisoner and a republic hastily proclaimed in Paris. The new government, realising that a victorious Germany would demand territorial acquisitions, resolved to fight on. They began to muster new armies, and the Germans settled down to a grim siege of Paris. The starving city surrendered in January 1871, and the Prussian army staged a victory parade in it. France was forced to pay indemnities of 5 billion francs and cede Alsace-Lorraine. It was a bitter peace that would leave the French thirsting for revenge.

During the Siege of Paris, the German princes assembled in the Hall of Mirrors of the Palace of Versailles and proclaimed the Prussian King Wilhelm I as the "German Emperor" on 18 January 1871. The German Empire was thus founded, with 25 states, three of which were Hanseatic free cities, and Bismarck, again, served as Chancellor. It was dubbed the "Little German" solution, since Austria was not included. The new empire was characterised by a great enthusiasm and vigor. There was a rash of heroic artwork in imitation of Greek and Roman styles, and the nation possessed a vigorous, growing industrial economy, while it had always been rather poor in the past. The change from the slower, more tranquil order of the old Germany was very sudden, and many, especially the nobility, resented being displaced by the new rich. And yet, the nobles clung stubbornly to power, and they, not the bourgeois, continued to be the model that everyone wanted to imitate. In imperial Germany, possessing a collection of medals or wearing a uniform was valued more than the size of one's bank account, and Berlin never became a great cultural center as London, Paris, or Vienna were. The empire was distinctly authoritarian in tone, as the 1871 constitution gave the emperor exclusive power to appoint or dismiss the chancellor. He also was supreme commander-in-chief of the armed forces and final arbiter of foreign policy. But freedom of speech, association, and religion were nonetheless guaranteed by the constitution.

Bismarck's domestic policies as Chancellor of Germany were characterised by his fight against perceived enemies of the Protestant Prussian state. In the so-called Kulturkampf (1872–1878), he tried to limit the influence of the Roman Catholic Church and of its political arm, the Catholic Centre Party, through various measures—like the introduction of civil marriage—but without much success. The Kulturkampf antagonised many Protestants as well as Catholics, and was eventually abandoned. Millions of non-Germans subjects in the German Empire, like the Polish, Danish and French minorities, were discriminated against [1][2] and a policy of Germanisation was implemented.

The other perceived threat was the rise of the Socialist Workers' Party (later known as the Social Democratic Party of Germany), whose declared aim was the establishment of a new socialist order through the transformation of existing political and social conditions. From 1878, Bismarck tried to repress the social democratic movement by outlawing the party's organisation, its assemblies and most of its newspapers. Through the introduction of a social insurance system, on the other hand, he hoped to win the support of the working classes for the Empire.

Bismarck's post-1871 foreign policy was conservative and basically aimed at security and preventing the dreaded scenario of a Franco-Russian alliance, which would trap Germany between the two in a war.

The Three Emperor's League (Dreikaisersbund) was signed in 1872 by Russia, Austria and Germany. It stated that republicanism and socialism were common enemies and that the three powers would discuss any matters concerning foreign policy. Bismarck needed good relations with Russia in order to keep France isolated. In 1877-1878, Russia fought a victorious war with the Ottoman Empire and attempted to impose the Treaty of San Stefano on it. This upset the British in particular, as they were long concerned with preserving the Ottoman Empire and preventing a Russian takeover of the Bosporous Straits. Germany hosted the Congress of Berlin, whereby a more moderate peace settlement was agreed to. Afterwards, Russia turned its attention eastward to Asia and remained largely inactive in European politics for the next 25 years. Germany had no direct interest in the Balkans however, which was largely an Austrian and Russian sphere of influence, although King Carol of Romania was a German prince.

In 1879, Bismarck formed a Dual Alliance of Germany and Austria-Hungary, with the aim of mutual military assistance in the case of an attack from Russia, which was not satisfied with the agreement reached at the Congress of Berlin.

The establishment of the Dual Alliance led Russia to take a more conciliatory stance, and in 1887, the so-called Reinsurance Treaty was signed between Germany and Russia: in it, the two powers agreed on mutual military support in the case that France attacked Germany, or in case of an Austrian attack on Russia.

In 1882, Italy joined the Dual Alliance to form a Triple Alliance. Italy wanted to defend its interests in North Africa against France's colonial policy. In return for German and Austrian support, Italy committed itself to assisting Germany in the case of a French military attack.

For a long time, Bismarck had refused to give in to Crown Prince Wilhelm II's aspirations of making Germany a world power through the acquisition of German colonies ("a place in the sun", originally a statement of Bernhard von Bülow). Bismarck wanted to avoid tensions between the European great powers that would threaten the security of Germany at all cost. But when, between 1880 and 1885, the foreign situation proved auspicious, Bismarck gave way, and a number of colonies were established overseas: in Africa, these were Togo, the Cameroons, German South-West Africa and German East Africa; in Oceania, they were German New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago and the Marshall Islands. In fact, it was Bismarck himself who helped initiate the Berlin Conference of 1885. He did it "establish international guidelines for the acquisition of African territory," (see Colonisation of Africa). This conference was an impetus for the "Scramble for Africa" and "New Imperialism".

In 1888, the old emperor William I died at the age of 90. His son Frederick III, the hope of German liberals, succeeded him, but was already stricken with throat cancer and died three months later. Frederick's son William II then became emperor at the age of 29. He was the antithesis of old, conservative Germans like Bismarck, addicted to the new imperialism that was taking place in Asia and Africa. He sought to make Germany a great world power with a navy to rival Britain's. Bismarck hoped to marginalise him just as he had marginalised his grandfather, but William II was on to Bismarck's tricks, and desired to be his own master. Having a left arm withered by childhood polio, he was painfully insecure and desired above all to be loved by the people. Bismarck's schemes to dominate the emperor and hold onto his own power failed, and he was forced to resign in March 1890. He died in 1898, spending his last years writing his memoirs and attacking William II (despite the latter's attempts at reconciliation).

Wilhelminian Era

Alliances and diplomacy

The young Kaiser sought aggressively to increasing Germany's influence in the world (Weltpolitik). After the removal of Bismarck, foreign policy was in the hands of the erratic Kaiser, who played an increasingly reckless hand, and the foreign office, under the intellectual leadership of Friedrich von Holstein.[21] The foreign office argued that long-term coalition between France and Russia had to fall apart, secondly Russia and Britain would never get together; finally that Britain would eventually seek an alliance with Germany. Germany refused to renew its treaties with Russia. But Russia did form a closer relationship with France by the Dual Alliance of 1894, since both were worried about the possibilities of German aggression. Furthermore, Anglo German relations cooled as Germany aggressively tried to build a new empire and engaged in a naval race with Britain; London refused to agree to the formal alliance that Germany sought. Berlin's analysis proved mistaken on every point, leading to Germany's increasing isolation and its dependence on the Triple Alliance, which brought together Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy. The Triple Alliance was undermined by differences between Austria and Italy, and in 1915 Italy switched sides.[22]

Meanwhile the German Navy under Admiral Tirpitz had ambitions to rival the great British Navy, and dramatically expanded its fleet in the early 20th century to protect the colonies and exert power worldwide.[23] Tirpitz started a programme of warship construction in 1898. In 1890, Germany had gained the island of Heligoland in the North Sea from Britain in exchange for the African island of Zanzibar and proceeded to construct a great naval base there. This posed a direct threat to British hegemony on the seas, with the result that negotiations for an alliance between Germany and Britain broke down. The British however kept well ahead in the naval race by the introduction of the highly advanced new Dreadnought battleship in 1907.[24]

In the First Moroccan Crisis of 1905, Germany nearly came to blows with Britain and France when the latter attempted to establish a protectorate over Morocco. The Germans were upset at having not been informed about French intentions, and declared their support for Moroccan independence. William II made a highly provocative speech regarding this. The following year, a conference was held in which all of the European powers except Austria-Hungary (by now little more than a German satellite) sided with France. A compromise was brokered by the United States where the French relinquished some, but not all, control over Morocco.[25]

The Second Moroccan Crisis of 1911 saw another dispute over Morocco erupt when France tried to suppress a revolt there. Germany, still smarting from the previous quarrel, agreed to a settlement whereby the French ceded some territory in central Africa in exchange for Germany renouncing any right to intervene in Moroccan affairs. This confirmed French control over Morocco, which became a full protectorate of that country in 1912.

Colonies

Germans had dreamed of colonial imperialism since 1848.[26] Bismark began the process, and by 1884 had acquired German New Guinea.[27] By the 1890s, German colonial expansion in Asia and the Pacific (Kiauchau in China, the Marianas, the Caroline Islands, Samoa) led to frictions with Britain , Russia, Japan and the United States. The construction of the Baghdad Railway, financed by German banks, was designed to eventually connect Germany with the Turkish Empire and the Persian Gulf, but it also collided with British and Russian geopolitical interests. The largest colonial enterprises were in Africa[28], where the harsh treatment of the Nama and Herero in what is now Namibia in 1906-07 led to charges of genocide against the Germans.[29]

World War I and revolution

Imperialist power politics and nationalism were the causes of World War I, which started in August 1914. Germany stood behind its ally Austria in a confrontation with Serbia, and with Serbia's protector Russia, and with Russia's ally France. Germany fought on the side of Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire against Russia, France, Great Britain, Italy, Japan and several other smaller states, and against the United States starting in 1917. Fighting also spread to the Near East and the German colonies.

British security issues

In explaining why neutral Britain went to war with Germany, Kennedy (1980) recognized it was critical for war that Germany become economically more powerful than Britain, but he downplays the disputes over economic trade imperialism, the Baghdad Railway, confrontations in Eastern Europe, high-charged political rhetoric and domestic pressure-groups. Germany's reliance time and again on sheer power, while Britain increasingly appealed to moral sensibilities, played a role, especially in seeing the invasion of Belgium as a necessary military tactic or a profound moral crime. The German invasion of Belgium was not important because the British decision had already been made and the British were more concerned with the fate of France(pp 457-62). Kennedy argues that by far the main reason was London's fear that a repeat of 1870--when Prussia and the German states smashed France--would mean Germany, with a powerful army and navy, would control the English Channel, and northwest France. British policy makers insisted that would be a catastrophe for British security.[30]

In the west, Germany sought a quick victory by encircling Paris using the Schlieffen Plan. But it failed due to Belgian resistance, Berlin's diversion of troops, and very stiff French resistance on the Marne, north of Paris. The Western Front became an extremely bloody battleground until early 1918, with forces moving a few hundred yards at best. In the east there were decisive victories against the Russian army, the trapping and defeat of large parts of the Russian contingent at the Battle of Tannenberg, followed by huge Austrian and German successes led to a breakdown of Russian forces and an imposed peace on the newly created USSR under Lenin. Churchill ordered a naval blockade in the North Sea which lasted until 1919, crippling Germany's supplies of raw materials and foodstuffs. The entry of the United States into the war in 1917 following Germany's declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare marked a decisive turning-point against Germany.

The end of October 1918, in Kiel, in northern Germany, saw the beginning of the German Revolution of 1918–19. Units of the German Navy refused to set sail for a last, large-scale operation in a war which they saw as good as lost, initiating the uprising. On 3 November, the revolt spread to other cities and states of the country, in many of which so-called workers' and soldiers' councils were established.

Kaiser Wilhelm II and all German ruling princes abdicated. On 9 November 1918, the Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann proclaimed a Republic. On 11 November, the Compiègne armistice ending the war was signed. In accordance with the Social Democratic government by early 1919 the revolution was violently put down with the aid of the nascent Reichswehr and the Freikorps.

Weimar Republic

On 28 June 1919 the Treaty of Versailles was signed. Germany was to cede Alsace-Lorraine, Eupen-Malmédy, North Schleswig, and the Memel area. All German colonies were to be handed over to the British and French. Poland was restored and most of the provinces of Posen and West Prussia, and some areas of Upper Silesia were reincorporated into the reformed country after plebiscites and independence uprisings. The left and right banks of the Rhine were to be permanently demilitarised. The industrially important Saarland was to be governed by the League of Nations for 15 years and its coalfields administered by France. At the end of that time a plebiscite was to determine the Saar's future status. To ensure execution of the treaty's terms, Allied troops would occupy the left (German) bank of the Rhine for a period of 5–15 years. The German army was to be limited to 100,000 officers and men; the general staff was to be dissolved; vast quantities of war material were to be handed over and the manufacture of munitions rigidly curtailed. The navy was to be similarly reduced, and no military aircraft were allowed. Germany and its allies were to accept the sole responsibility of the war, in accordance with the War Guilt Clause, and were to pay financial reparations for all loss and damage suffered by the Allies.

The humiliating peace terms provoked bitter indignation throughout Germany, and seriously weakened the new democratic regime.

On 11 August 1919 the Weimar constitution came into effect, with Friedrich Ebert as first President.

The two biggest enemies of the new democratic order, however, had already been constituted. In December 1918, the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) was founded, followed in January 1919 by the establishment of the German Workers' Party, later known as the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP). Both parties would make reckless use of the freedoms guaranteed by the new constitution in their fight against the Weimar Republic.

In the first months of 1920, the Reichswehr was to be reduced to 100,000 men, in accordance with the Treaty of Versailles. This included the dissolution of many Freikorps – units made up of volunteers. In an attempt at a coup d'état in March 1920, the Kapp Putsch, extreme right-wing politician Wolfgang Kapp let Freikorps soldiers march on Berlin and proclaimed himself Chancellor of the Reich. After four days the coup d'état collapsed, due to popular opposition and lack of support by the civil servants and the officers. Other cities were shaken by strikes and rebellions, which were bloodily suppressed.

Faced with animosity from Britain and France and the retreat of American power from Europe, in 1922 Germany was the first state to establish diplomatic relations with the new Soviet Union. Under the Treaty of Rapallo, Germany accorded the Soviet Union de jure recognition, and the two signatories mutually cancelled all pre-war debts and renounced war claims.

When Germany defaulted on its reparation payments, French and Belgian troops occupied the heavily industrialised Ruhr district (January 1923). The German government encouraged the population of the Ruhr to passive resistance: shops would not sell goods to the foreign soldiers, coal-mines would not dig for the foreign troops, trams in which members of the occupation army had taken seat would be left abandoned in the middle of the street. The passive resistance proved effective, insofar as the occupation became a loss-making deal for the French government. But the Ruhr fight also led to hyperinflation, and many who lost all their fortune would become bitter enemies of the Weimar Republic, and voters of the anti-democratic right. See 1920s German inflation.

In September 1923, the deteriorating economic conditions led Chancellor Gustav Stresemann to call an end to the passive resistance in the Ruhr. In November, his government introduced a new currency, the Rentenmark (later: Reichsmark), together with other measures to stop the hyperinflation. In the following six years the economic situation improved. In 1928, Germany's industrial production even regained the pre-war levels of 1913.

On the evening of 8 November 1923, six hundred armed SA men surrounded a beer hall in Munich, where the heads of the Bavarian state and the local Reichswehr had gathered for a rally. The storm troopers were led by Adolf Hitler. Born in 1889 in Austria, a former volunteer in the German army during WWI, now a member of a new party called NSDAP, he was largely unknown until then. Hitler tried to force those present to join him and to march on to Berlin to seize power (Beer Hall Putsch). Hitler was later arrested and condemned to five years in prison, but was released at the end of 1924 after less than one year of detention.

The national elections of 1924 led to a swing to the right (Ruck nach rechts). Field Marshal Hindenburg, a supporter of the monarchy, was elected President in 1925.

In October 1925 the Treaty of Locarno was signed between Germany, France, Belgium, the United Kingdom and Italy, which recognised Germany's borders with France and Belgium. Moreover, Britain, Italy and Belgium undertook to assist France in the case that German troops marched into the demilitarised Rheinland. The Treaty of Locarno paved the way for Germany's admission to the League of Nations in 1926.

The stock market crash of 1929 on Wall Street marked the beginning of the Great Depression. The effects of the ensuing world economic crisis were also felt in Germany, where the economic situation rapidly deteriorated. In July 1931, the Darmstätter und Nationalbank - one of the biggest German banks - failed, and, in early 1932, the number of unemployed rose to more than 6,000,000.

In addition to the flagging economy came political problems, due to the inability by the political parties represented in the Reichstag to build a governing majority. In March 1930, President Hindenburg appointed Heinrich Brüning Chancellor. To push through his package of austerity measures against a majority of Social Democrats, Communists and the NSDAP, Brüning made use of emergency decrees, and even dissolved Parliament. In March and April 1932, Hindenburg was re-elected in the German presidential election of 1932.

Of the many splinter parties the NSDAP was the largest in the national elections of 1932. The Prussian government had been ousted by a coup (Preussenschlag) in 1932. On 31 July 1932 the NSDAP had received 37.3% of the votes, and in the election on 6 November 1932 it received less, but still the largest share, 33.1, making it the biggest party in the Reichstag. The Communist KPD came third, with 15%. Together, the anti-democratic parties of right and left were now able to hold the majority of seats in Parliament. The NSDAP was particularly successful among young voters, who were unable to find a place in vocational training, with little hope for a future job; among the petite bourgeoisie (lower middle class) which had lost its assets in the hyperinflation of 1923; among the rural population; and among the army of unemployed.

On 30 January 1933, pressured by former Chancellor Franz von Papen and other conservatives, President Hindenburg finally appointed Hitler Chancellor.

Weimar Republic Results of Elections 1919-1933, Electiontions 1932, 1933

Third Reich

Establishment of the Nazi regime

In order to secure a majority for his NSDAP in the Reichstag, Hitler called for new elections. On the evening of 27 February 1933, a fire was set in the Reichstag building. Hitler swiftly blamed an alleged Communist uprising, and convinced President Hindenburg to sign the Reichstag Fire Decree. This decree, which would remain in force until 1945, repealed important political and human rights of the Weimar constitution. Communist agitation was banned, but at this time not the Communist Party itself.

Eleven thousand Communists and Socialists were arrested and brought into concentration camps, where they were at the mercy of the Gestapo, the newly established secret police force (9,000 were found guilty and most executed). Communist Reichstag deputies were taken into protective custody (despite their constitutional privileges).

Despite the terror and unprecedented propaganda, the last free General Elections of 5 March 1933, while resulting in 43.9% failed to bring the majority for the NSDAP that Hitler had hoped for. Together with the German National People's Party (DNVP), however, he was able to form a slim majority government. With accommodations to the Catholic Centre Party, Hitler succeeded in convincing a required two-thirds of a rigged Parliament to pass the Enabling act of 1933 which gave his government full legislative power. Only the Social Democrats voted against the Act. The Enabling Act formed the basis for the dictatorship, dissolution of the Länder; the trade unions and all political parties other than the National Socialist (Nazi) Party were suppressed. A centralised totalitarian state was established, no longer based on the liberal Weimar constitution. Germany left the League of Nations. The coalition parliament was rigged on this fateful 23 March 1933 by defining the absence of arrested and murdered deputies as voluntary and therefore cause for their exclusion as wilful absentees. Subsequently in July the Centre Party was voluntarily dissolved in a quid pro quo with the Pope under the anti-communist Pope Pius XI for the Reichskonkordat; and by these manoeuvres Hitler achieved movement of these Catholic voters into the Nazi party, and a long-awaited international diplomatic acceptance of his regime. It is interesting to note however that according to Professor Dick Geary the Nazis gained a larger share of their vote in Protestant than in Catholic areas of Germany in elections held between 1928 to November 1932[31] The Communist Party was proscribed in April 1933 . On the weekend of 30 June 1934, he gave order to the SS to seize Röhm and his lieutenants, and to execute them without trial (known as the Night of the Long Knives). Upon Hindenburg's death on 2 August 1934, Hitler's cabinet passed a law proclaiming the presidency vacant and transferred the role and powers of the head of state to Hitler as Führer und Reichskanzler (leader and chancellor).

However, many leaders of the Nazi SA were disappointed. The Chief of Staff of the SA, Ernst Röhm, was pressing for the SA to be incorporated into the army. Hitler had long been at odds with Röhm and felt increasingly threatened by these plans and in the "Night of the Long Knives" in 1934 killed Röhm and the top SA leaders using their notorious homosexuality as an excuse.[32]

The SS became an independent organisation under the command of the Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler. He would become the supervisor of the Gestapo and of the concentration camps, soon also of the ordinary police. Hitler also established the Waffen-SS as a separate troop.

Jews

The regime showed particular hostility towards the Jews, which were the target of unending propaganda attacks. In 1933 all jewish civil servants and academics were fired. In September 1935, the Reichstag passed the Nuremberg race laws. Jews lost their German citizenship, and were banned from marrying non-Jewish Germans. About 500,000 individuals were affected by the new rules. About half of Germany's 500,000 Jews fled before 1939, after which escape became almost impossible.[33]

Military

Hitler re-established the German air force and reintroduced universal military service. The open rearmament was in flagrant breach of the Treaty of Versailles, but neither the United Kingdom, France or Italy went beyond issuing notes of protest.

In 1936 German troops marched into the demilitarised Rhineland. Britain and France did not intervene. The move strengthened Hitler's standing in Germany. His reputation swelled further with the 1936 Summer Olympics, which were held in the same year in Berlin, and which proved another great propaganda success for the regime as orchestrated by master propagandizt Joseph Goebbels.

Women

Historians have paid special attention to the efforts by Nazi Germany to reverse the gains women made before 1933, especially in the relatively liberalWeimar Republic.[34] It appears the role of women in Nazi Germany changed according to circumstances. Theoretically the Nazis believed that women must be subservient to men, avoid careers, devote themselves to childbearing and child-rearing, and be a helpmate of the traditional dominant father in the traditional family.[35] However, before 1933, women played important roles in the Nazi organization and were allowed some autonomy to mobilize other women. After Hitler came to power in 1933, the activist women were replaced by bureaucratic women who emphasized feminine virtues, marriage, and childbirth. As Germany prepared for war, large numbers were incorporated into the public sector and with the need for full mobilization of factories by 1943, all women were required to register with the employment office. Hundreds of thousands of women served in the military as nurses, and support personnel, and another hundred thousand served in the Luftwaffe helping to operate the anti--aircraft systems.[36] Women's wages remained unequal and women were denied positions of leadership or control.[37]

Expansion and defeat

After establishing the "Rome-Berlin axis" with Mussolini, and signing the Anti-Comintern Pact with Japan - which was joined by Italy a year later in 1937 - Hitler felt able to take the offensive in foreign policy. On 12 March 1938, German troops marched into Austria, where an attempted Nazi coup had been unsuccessful in 1934. When Hitler entered Vienna, he was greeted by loud cheers. Four weeks later, 99% of Austrians voted in favour of the annexation (Anschluss) of their country to the German Reich. Hitler thereby fulfilled the old idea of an all encompassing German Reich with the inclusion of Austria - the "greater Germany" solution that Bismarck had shunned when, in 1871, he united the German-speaking lands under Prussian leadership. Although the annexation denounced the Treaty of Saint-Germain, which expressedly forbade the unification of Austria with Germany, the western powers once again merely protested.

After Austria, Hitler turned to Czechoslovakia, where the 3.5 million-strong Sudeten German minority was demanding equal rights and self-government. At the Munich Conference of September 1938, Hitler, the Italian leader Benito Mussolini, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier agreed upon the cession of Sudeten territory to the German Reich by Czechoslovakia. Hitler thereupon declared that all of German Reich's territorial claims had been fulfilled. However, hardly six months after the Munich Agreement, in March 1939, Hitler used the smoldering quarrel between Slovaks and Czechs as a pretext for taking over the rest of Czechoslovakia as the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. In the same month, he secured the return of Memel from Lithuania to Germany. British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was forced to acknowledge that his policy of appeasement towards Hitler had failed.

In six years, the Nazi regime prepared the country for World War II. The Nazi leadership attempted to remove or subjugate the Jewish population of Nazi Germany and later in the occupied countries through forced deportation and, ultimately, genocide now known as the Holocaust. A similar policy applied to the various ethnic and national groups considered subhuman such as Poles , Roma or Russians. These groups were seen as threats to the purity of Germany's Aryan race. There were also many groups, such as homosexuals, the mentally handicapped and those who were physically challenged from birth, which were singled out as being detrimental to Aryan purity. After annexing the Sudetenland border country of Czechoslovakia (October 1938), and taking over the rest of the Czech lands as a protectorate (March 1939), the German Reich and the Soviet Union invaded Poland on first September 1939 predominantly as part of the Wehrmacht operation codenamed Fall Weiss. The invasion of Poland began World War II.