History of Montana: Difference between revisions

→Entrepreneurs: Havre |

→Entrepreneurs: Gibson |

||

| Line 129: | Line 129: | ||

===Entrepreneurs=== |

===Entrepreneurs=== |

||

Henry Sieben (1847-1937) came to Montana's gold fields in 1864, was a farm laborer, prospector, and freighter, then turned to livestock raising along the Smith River in 1870. In partnership with his brothers he raised cattle and became one of the territory's pioneer sheep ranchers in 1875. In 1879 and Henry moved his stock to the Lewistown area. He established a reputation as an excellent businessman and as someone who took care of his stock and employees. After ranching in the Culbertson area, Henry Sieben purchased ranches near Cascade and along Little Prickly Pear Creek, forming the Sieben Livestock Company. By 1907, these two ranches had become the heart of his cattle and sheep raising business which he directed from his home in Helena. Sieben became well known for his business approach to ranching and for his public and private philanthropies. His family continues to operate the Sieben Ranch Company today<ref> Dick Pace, "Henry Sieben: Pioneer Montana Stockman," ''Montana'' March 1979, Vol. 29 Issue 1, pp 2-15</ref>. |

Henry Sieben (1847-1937) came to Montana's gold fields in 1864, was a farm laborer, prospector, and freighter, then turned to livestock raising along the Smith River in 1870. In partnership with his brothers he raised cattle and became one of the territory's pioneer sheep ranchers in 1875. In 1879 and Henry moved his stock to the Lewistown area. He established a reputation as an excellent businessman and as someone who took care of his stock and employees. After ranching in the Culbertson area, Henry Sieben purchased ranches near Cascade and along Little Prickly Pear Creek, forming the Sieben Livestock Company. By 1907, these two ranches had become the heart of his cattle and sheep raising business which he directed from his home in Helena. Sieben became well known for his business approach to ranching and for his public and private philanthropies. His family continues to operate the Sieben Ranch Company today<ref> Dick Pace, "Henry Sieben: Pioneer Montana Stockman," ''Montana'' March 1979, Vol. 29 Issue 1, pp 2-15</ref>. |

||

After seeing the falls of the Missouri River in central Montana, [[Paris Gibson]] (1830-1920) decided the location presented an ideal site for a town. Founding [[Great Falls, Montana]], in 1884, Gibson was inspired by a grandiose vision of an economically prosperous city that was also beautiful. He took an active role in the development of Great Falls, as well as Montana as a whole, making his voice heard on issues from dryland farming to the humane treatment of animals. While many of his visionary ideals have long since been passed by, his efforts at community building in the West serve as a unique example and provide an important perspective on the region's continuing development<ref>Richard B. Roeder, "A Settlement on the Plains: Paris Gibson and the Building of Great Falls," ''Montana'' Dec 1992, Vol. 42 Issue 4, pp 4-19 </ref>. |

|||

The Conrad families built a substantial banking business in north-central and northwestern Montana during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Banking houses at Fort Benton, Great Falls, and Kalispell, owned and managed by the families of William Conrad and Charles Conrad helped to finance Montana's economic development through an intricate pattern of familial, friendship, and business ties. Correspondent linkages to large metropolitan banks sustained the relatively small country banks by assuring them access to capital. The Conrad banks were aggressive in penetrating new lending markets and making inroads into the local farming, ranching, merchant, and manufacturing sectors. The banks grew in reputation and stature as the region developed, but remained single-unit, family-based enterprises. But Conrad's expanded across the international border into [[Alberta]] through the Conrad Circle Cattle Company<ref> Henry C. Klassen, "The Early Growth of the Conrad Banking Enterprise in Montana, 1880-1914," ''Great Plains Quarterly,'' Jan 1997, Vol. 17 Issue 1, pp 49-62</ref>. |

The Conrad families built a substantial banking business in north-central and northwestern Montana during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Banking houses at Fort Benton, Great Falls, and Kalispell, owned and managed by the families of William Conrad and Charles Conrad helped to finance Montana's economic development through an intricate pattern of familial, friendship, and business ties. Correspondent linkages to large metropolitan banks sustained the relatively small country banks by assuring them access to capital. The Conrad banks were aggressive in penetrating new lending markets and making inroads into the local farming, ranching, merchant, and manufacturing sectors. The banks grew in reputation and stature as the region developed, but remained single-unit, family-based enterprises. But Conrad's expanded across the international border into [[Alberta]] through the Conrad Circle Cattle Company<ref> Henry C. Klassen, "The Early Growth of the Conrad Banking Enterprise in Montana, 1880-1914," ''Great Plains Quarterly,'' Jan 1997, Vol. 17 Issue 1, pp 49-62</ref>. |

||

Revision as of 17:57, 6 September 2010

The history of the state of Montana in the United States.

Indigenous peoples

Archeological evidence has shown indigenous peoples lived in the area thousands of years ago. For example, rock art in Pictograph Cave six miles (10 km) south of Billings has been dated, showing human presence in the area more than 2,100 years ago. The artist people were likely preceded and certainly followed by other cultures.

Historically, the indigenous Crow Indians, a Siouan-language people, were known to have inhabited the area of present-day south-central Montana and northern Wyoming from about 1700 onward. Their arrival in the area was preceded by a 100-year migration from the Great Lakes area to the northern Rocky Mountains (present-day Alberta), south to the Great Salt Lake, east to the southern plains, and finally north to the Big Horn Mountains and the Yellowstone River.[1] This area became the new homeland of the Crow, who have continued to inhabit it.

Apsáalooke ("people (or children) of the large-beaked bird") is what the Crow Tribe were called (also known as exonym) by neighboring tribes. The meaning of their name was misunderstood by the French, who called them gens du corbeaux (people of the crow). After the introduction of the horse by Spanish explorers and adoption by the Crow by 1725, they had an enlarged ability to migrate. They adapted their shelters to the portable form of tipis made with bison skins and wooden poles. The people were known to construct some of the largest tipis among the Great Plains tribes. The Crow also bred, trained and owned more horses than any other Plains tribe; in 1914, their horse herds numbered approximately 30,000-40,000 head. By 1921 they held only about 1,000 head because of adopting more sedentary lives after being confined to reservations. In addition, the US government was then trying to reduce the wild horse population and may have claimed Crow horses. The Crow were among the few Native Americans to keep many companion dogs; one source counted 500 to 600. Unlike some other tribes, they did not consume dog as a food. The Crow were nomads following the buffalo.

The Cheyenne have a reservation in the southeastern portion of the state. The Cheyenne language is part of the larger Algonquian language group, but it is one of the few Plains Algonquian languages to have developed tonal characteristics. The closest linguistic relatives of the Cheyenne language are Arapaho and Ojibwa (Chippewa). Nothing is absolutely known about the Cheyenne people before the 16th century, when they were recorded in European explorers' and traders' accounts[2].

The Blackfeet, Assiniboine, and Gros Ventres have reservations in the central and north-central area. Prior to the reservation era, the Blackfoot were fiercely independent and highly successful warriors whose territory stretched from the North Saskatchewan River along what is now Edmonton, Alberta in Canada, to the Yellowstone River of Montana, and from the Rocky Mountains and along the Saskatchewan River past Regina, Canada. The Blackfoot were nomadic, following the buffalo herds. Survival required their being in the proper place at the proper time. For almost half the year in the long northern winter, the Blackfoot people lived in various winter camps dispersed perhaps a day's march apart along a wooded river valley. They did not move camp in winter unless food for the people and horses or firewood became depleted[3].

The Assiniboine, also known by the Ojibwe exonym Asiniibwaan ("Stone Sioux"), are originally from the Northern Great Plains area of North America, specifically present-day Montana and parts of Saskatchewan, Alberta and southwestern Manitoba around the US/Canadian border. They were well known throughout much of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Images of Assiniboine people were painted by such 19th century artists as Karl Bodmer and George Catlin. The Assiniboine have many similarities to the Lakota (Sioux) people in lifestyle, linguistics, and cultural habits. They are considered a band of the Nakoda, or middle division of the Lakota. Pooling their research, historians, linguists and anthropologists have concluded the Assiniboine broke away from other Lakota bands in the 17th century.

The Gros Ventre are located in north-central Montana. Gros Ventre is the exonym given by the French, who misinterpreted their sign language. The people call themselves (autonym) A'ani or A'aninin (white clay people), perhaps related to natural formations. They were called the Atsina by the Assiniboine, but the latter were their historical enemies and the name is considered inaccurate and derogatory. The A'ani have 3,682 members and they share Fort Belknap Indian Reservation with the Assiniboine, their longtime enemies. The A'ani are classified as a band of Arapaho; they speak a variant of Arapaho called Gros Ventre or Atsina.

The Kootenai and Salish live in the west. The Kootenai name is also spelled Kutenai or Ktunaxa (pronounced in English as /k ̩tuˈnæ.hæ/.) They are one of three tribes of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation in Montana, and they form the Ktunaxa Nation in British Columbia, Canada. There are also Kootenai populations in Idaho and Washington.

The Bitterroot Salish and Pend d'Oreilles tribes live on the Flathead Indian Reservation. The smaller Pend d'Oreille and Kalispel tribes are found around Flathead Lake and the western mountains, respectively.

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 sparked interest in knowing more of the vast lands of the West. President Thomas Jefferson, an advocate of exploration and scientific inquiry, had the Congress appropriate $2,500, "to send intelligent officers with ten or twelve men, to explore even to the Western ocean". They were to study, map and record information on the Indians, the natural history, the geology, terrain, and river systems. Eventually the Louis and Clark Expedition was expanded to 37 men with 32 men continuing on from Fort Mandan on the Missouri River while five men returned with preliminary discoveries. Eventually the expedition floated down the Columbia River to the Pacific. On the return trip on July 3, 1806 after crossing the Continental Divide, the Corps split into two teams so Lewis could explore and map the Marias River.

William Clark with most of the men went down the Yellowstone River to explore and map it. He signed his name 25 miles (40 km) northeast of Billings, Montana . The inscription consists of his signature and the date July 25, 1806. Clark claimed he climbed the sandstone pillar and "had a most extensive view in every direction on the Northerly Side of the river". The pillar was named by Clark after the son of Sacagawea who was the Shoshone woman (wife of a French trapper they had hired) who had helped to guide the expedition and had acted as an interpreter. Clark had called Sacagawea's son "Pompy" and his original name for the outcropping was "Pompys Tower". It was later changed (1814) to the current title. Clark's inscription is the only remaining physical evidence found along the route that was followed by the expedition.

Lewis' group of four men met some Blackfeet Indians. Their initial meeting was cordial, but during the night, the Blackfeet tried to steal their weapons. In the ensuing struggle, two Indians were killed, the only native deaths attributable to the expedition. To prevent further bloodshed, the group of four—Lewis, Drouillard, and the two Field brothers—fled over 100 miles (160 km) in a day before they camped again. Clark, meanwhile, had entered Crow territory. The Crow tribe were known as horse thieves at the end of one night, half of Clark's horses were gone, even though not a single Crow was seen. Lewis and Clark stayed separated until they reached the confluence of the Yellowstone River and Missouri Rivers on August 11, 1806. Clark's team had floated down the rivers in bull boats they had made. After reuniting, one of their hunters, Pierre Cruzatte, blind in one eye and nearsighted in the other, mistook Lewis for an elk and fired, injuring Lewis in the thigh. After the two groups were reunited they were able to quickly return to St Louis, Missouri by floating down the Missouri River on boats they constructed.

First permanent settlement

Stevensville is officially recognized as the first permanent settlement in the state of Montana. Forty-eight years before Montana became the nation's 41st state, Stevensville was settled by Jesuit missionaries at the request of the Bitter Root Salish Indians.

Through interactions with Iroquois Indians between 1812 and 1820, the Bitter Root Salish Indians learned about Christianity and Jesuit missionaries (blackrobes) that worked with Indian tribes teaching about agriculture, medicine, and religion. Interest in these “blackrobes” grew among the Salish and, in 1831, four young Salish men were dispatched to St. Louis, Missouri to request a “blackrobe” to return with them to their homeland of present day Stevensville. The four Salish men were directed to the home and office of William Clark (of Lewis and Clark fame) to make their request. At that time Clark was in charge of administering the territory they called home. Through the perils of their trip, two of the Indians died at the home of General Clark. The remaining two Salish men secured a visit with St. Louis Bishop Joseph Rosati, who assured them that missionaries would be sent to the Bitter Root Valley when funds and missionaries were available in the future.

Again in 1835 and 1837 the Bitter Root Salish dispatched men to St. Louis to request missionaries but to no avail. Finally in 1839 a group of Iroquois and Salish met Father Pierre-Jean DeSmet in Council Bluffs, Iowa. The meeting resulted in Fr. DeSmet promising to fulfill their request for a missionary the following year.

DeSmet arrived in present-day Stevensville on September 24, 1841, and called the settlement St. Mary’s. Construction of a chapel immediately began, followed by other permanent structures including log cabins and Montana's first pharmacy.

In 1850 Major John Owen arrived in the valley and set up camp north of St. Mary's. In time, Major Owen established a trading post and military strong point named Fort Owen, which served the settlers, Indians, and missionaries in the valley.

Military history

Fort Shaw

Fort Shaw (Montana Territory) was established in the spring of 1867. It is located west of Great Falls in the Sun River Valley and was one of three posts authorized to be built by Congress in 1865. The other two posts in the Montana Territory were Camp Cooke on the Judith River and Fort C.F. Smith on the Bozeman Trail in south central Montana Territory. Fort Shaw was built of adobe and lumber by the 13th Infantry. The fort had a parade ground that was 400 feet (120 m) square, and consisted of barracks for officers, a hospital, and a trading post, and could house up to 450 soldiers. Completed in 1868, its soldiers were mainly used to guard the Benton-Helena Road, the major supply-line from Fort Benton, which was the head of navigation on the Missouri River, to the gold mining districts in southwestern Montana Territory. The fort was occupied by military personnel until 1891.

After the close of the military post, the government established Fort Shaw as a school to provide industrial training to young Native Americans. The Fort Shaw Indian Industrial School was opened on April 30, 1892. The school had at one time 17 faculty members, 11 Indian assistants, and 300 students. The school made use of over 20 of the buildings built by the Army.

Custer and the Battle of the Little Big Horn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn — which is also called Custer's Last Stand and by Native Americans, the Battle of the Greasy Grass — was an armed engagement between a Lakota-Northern Cheyenne combined force and the 7th Cavalry of the United States Army. It occurred June 25–June 26, 1876, near the Little Bighorn River in eastern Montana Territory near present day Hardin, Montana. Custer with 257 men attacked a much larger and in three hours was completely annihilated. The Teton were defeated in a series of subsequent battles by the reinforced U.S. Army who continued attacking even in the winter, and were herded back onto reservations, by preventing buffalo hunts and enforcing government food-distribution policies to "friendlies" only. The Lakota were compelled to sign a treaty in 1877 ceding the Black Hills to the United States, but a low-intensity war continued.

Montana Territory

Subsequent to the Lewis and Clark Expedition and after the finding of gold in the region in the late 1850s, Montana became a United States territory (Montana Territory) on May 26, 1864 and the 41st state on November 8, 1889.

|

|

|

|

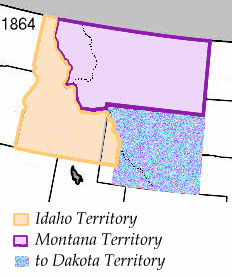

The reorganization of the Idaho Territory in 1864, showing the newly-created Montana Territory. |

The territory was organized out of the existing Idaho Territory by Act of Congress and signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on May 28, 1864. The areas east of the continental divide had been previously part of the Nebraska and Dakota territories and had been acquired by the United States in the Louisiana Purchase.

The territory also included a portion of the Idaho Territory west of the continental divide and east of the Bitterroot Range, which had been acquired by the United States in the Oregon Treaty, and originally included in the Oregon Territory. (The part of the Oregon Territory that became part of Montana had been split off as part of the Washington Territory.)

The boundary between the Washington Territory and Dakota Territory was the Continental Divide (as shown on the 1861 map), however the boundary between the Idaho Territory and the Montana Territory followed the Bitterroot Range north of 46°30'N (as shown on the 1864 map). Popular legend says a drunken survey party followed the wrong mountain ridge and mistakenly moved the boundary west into the Bitterroot Range.

Contrary to legend, the boundary is precisely where the United States Congress intended. The Organic Act of the Territory of Montana[4] defines the boundary as extending from the modern intersection of Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming at:

"the forty-fourth degree and thirty minutes of north latitude; thence due west along said forty-fourth degree and thirty minutes of north latitude to a point formed by its intersection with the crest of the Rocky Mountains; thence following the crest of the Rocky Mountains northward till its intersection with the Bitter Root Mountains; thence northward along the crest of the Bitter Root Mountains to its intersection with the thirty-ninth degree of longitude west from Washington; thence along said thirty-ninth degree of longitude northward to the boundary line of the British possessions"

The boundaries of the territory did not change during its existence.

Montana was admitted to the Union as the State of Montana on November 8, 1889.

Railroads

The railroads were the engine of settlement in the state. Major development occurred in the 1880s. The Northern Pacific Railroad was given land grants by the federal government so that it could borrow money to build its system, reaching Billings in 1882. The federal government kept every other section of land, and gave it away to homesteaders. At first the railroad sold much of its holdings at low prices to land speculators in order to realize quick cash profits, and also to eliminate sizable annual tax bills. By 1905 the company changed its land policies as it realize it had been a costly mistake to have sold so much land at wholesale prices. With better railroad service and improved methods of farming the Northern Pacific easily sold what had been heretofore "worthless" land directly to farmers at good prices. By 1910 the railroad's holdings in North Dakota had been greatly reduced[5]. Meanwhile the Great Northern Railroad energetically promoted settlement along its lines in the northern part of the state. The Great Northern bought its lands from the federal government -- it received no land grants -- and resold them to farmers one by one. It operated agencies in Germany and Scandinavia that promoted its lands, and brought families over at low cost.[6][7]

The village of Taft, located in western Montana near the Idaho border, was representative of numerous short lived railroad construction camps. In 1907-09 Taft served as a boisterous construction town for the Chicago, Milwaukee, & St. Paul Railroad. The camp included many ethnic groups, numerous saloons and prostitutes, and substantial violence. When construction was finished, the camp was abandoned[8].

In 1882 the Northern Pacific platted Livingston, Montana, a major division point, repair and maintenance center, and gateway to Yellowstone National Park. Built in symmetrical fashion along both sides of the track, the city grew to 7,000 by 1914. Several structures built between 1883 and 1914 still exist and provide a physical record of the era and indicate the city's role as a rail and tourist center. The Northern Pacific depot reflects the desire to impress the tourists who disembarked here for Yellowstone Park, and the railroad's machine shops reveal the city's industrial history[9].

Women

Efforts to write woman suffrage into Montana's 1889 constitution failed. Montana women, especially "society women," did not strongly support the suffragists. Help from national leaders and from Jeannette Rankin (1880-1973), led to success in 1914 when voters ratified a suffrage amendment passed by the legislature in 1913. In 1916, Rankin, a Republican, became the first woman ever elected to Congress. She was elected again in 1940. Rankin was a peace activist, who voted against American entry into what World War I and World War II[10].

The status of women in the 19th-century West has drawn the attention of numerous scholars, whose interpretations fall into three types: 1) the Frontier school influenced by Frederick Jackson Turner, which argues that the West was a liberating experience for women and men; 2) the reactionists, who view the West as a place of drudgery for women, who reacted unfavorably to the isolation and the work in the West; and 3) those writers who claim the West had no effect on women's lives, that it was a static, neutral frontier. Cole (1990) uses legal records to argue that Turner thesis best explains the improvement in women's status in Montana and the early achievement of suffrage in 1914[11].

Women's clubs expressed the interests, needs, and beliefs of middle class women at the turn of the century. While accepting the domestic role established by the cult of true womanhood, their reformist activities reveal a persistent demand for self-expression outside the home. Homesteading was a significant experience for altering women's perceptions of their roles. They expressed their aesthetic interests in gardens, and organized social activities. Though these clubs allowed women to fulfill their traditional roles they also encouraged women to pursue social, intellectual, and community interests. Women took an active role in the Progressive Movement, especially in battles for suffrage, prohibition, better schools, church activities, charity work, and crime reduction[12].

Childbirth was serious and sometimes life threatening for rural women well into the 20th century. Although large families were favored by farm families, most women employing birth control methods to space their children and limit their family size. Pregnant women had little access to modern knowledge about prenatal care. Delivery was the big gamble; the great majority gave birth at home, with the services of a midwife or an experienced neighbor. Despite the increased availability of hospital care after the 1920s, modern medical benefits to mitigate the danger of childbirth were not available to most rural Montana women until the World War II era[13].

In rural Montana, very few single men attempted to operate a farm or ranch; farmers clearly understood the need for a hard-working wife, and numerous children, to handle the many chores, including child-rearing, feeding and clothing the family, managing the housework, feeding the hired hands, and, especially after the 1930s, handling the paperwork and financial details[14]

Economic history

Mining

Copper made Butte one of the most prosperous cities in the world, thanks to having what often called "the Richest Hill on Earth". From 1892 through 1903, the Anaconda mine in Butte was the largest copper-producing mine in the world. It produced more than $300 billion worth of metal in its lifetime. The nearby city of Anaconda was the dream child of industrialist Marcus Daly (1841-1900), whose Anaconda Copper Mining Company (ACM) by 1900 employed three-quarters of Montana's wage earners; it dominated the state's politics and press into the 1950s. The smelters in Anaconda process the copper mined in Butte. From 1884 to 1934, the Company fought industrial unionism; finally in 1901 workers there organized a local of the radical Western Federation of Miners (WFM). In 1916, the WFM became the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers (IUMMSW), one of the ten original unions of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in the 1930s. However, the union remained weak until 1934, when members joined with miners, other smelter workers, and some craft laborers in the region in a strike that forced the Company to negotiate. In the late 1940s the CIO purged unions controlled by Communists, which meant the expulsion of the IUMMSW and a bid for influence among smelter workers by the anticommunist United Steel Workers of America (USWA). In 1980, most of the copper mines and smelters were shut down, leaving a major cleanup mess for the Environmental Protection Agency[15].

Many mining camps were established in the late 19th century, some becoming established cities like Butte and Anaconda, which survived the closure of their mines. Others enjoyed a boom period then withered away, such as the town of Comet in central Jefferson County. It operated mines and processing mills from 1869 to 1941. At its height, Comet was a town of 12 blocks and 6 streets and by 1911 had extracted $13 million worth of metals (gold, silver, lead, zinc, and copper ore). Comet is now an abandoned and decaying relic of the past. The town's most prominent remains are the mill, office, and bunkhouse, which are leftovers from the last productive years in the 1920s and 1930s. Most of the other structures and buildings have collapsed from neglect[16]. Between 1900 and 1920 Kendall, in Fergus County, boomed as its low-grade gold ore responded to the cyanide process, then collapsed as the mines played out.

Metals manufacturing dominated life in four Montana communities - Anaconda, Black Eagle, East Helena, and Columbia Falls. The industrial workers who lived in the shadow of the smokestacks faced health hazards and job insecurity. Wives often worked to supplement the family income and after 1960 women increasingly worked outside the home. The smelters, usually the only workplace for young men who wished to remain in the community, created blue-collar towns. Residents expressed a love-hate relationship with the companies, which paid high wages for semi-skilled workers and supported community projects but were heavy-handed with the workers. Labor unions united the community workers and local business[17].

In 1903, the Socialist Party of America won its first victory west of the Mississippi when Anaconda, Montana, elected a socialist mayor, treasurer, police judge, and three councilmen. The Socialist Party had grown within the Montana labor movement. Initially, the Anaconda Copper Mining Company tolerated them, but when the Socialists gained political power and threatened to implement reform, the company systematically undermine the radical party. City workers and councilmen refused to cooperate with the new mayor, and the company began to fire Socialists. In the long run labor lost ground in Anaconda and the company exerted ever greater political control[18].

Coal

When strip mining of coal replaced cattle ranching as the primary occupation in a rural section of southern Montana encompassing the small settlements of Birney and Decker, the characteristic sense of community disappeared. The physical damage to the environment was an important factor as was the influx of miners who then outnumbered the original population. Most damaging, however, was the strife between pro- and anti-development factions in the community. Most of the inhabitants of Decker, convinced their old lifestyle had been destroyed, moved elsewhere. Residents around Birney, farther from the site of strip mining, remained divided on whether the changes had improved their quality of life[19].

Oil

Texaco operated a pipeline from Canada that went through Glendive in the early 1950s. After the discovery of oil in the Williston Basin, Glendive became an oil boom town. The small reserves of the basin, coupled with the expense and difficulty of moving the oil out of the area, brought the end of the oil boom in Glendive in 1954. However new deep drilling techniques after 1990 made it financially attractive to drill new wells in the Williston Basin, and the high price of oil created a regional boom in the 21st century.

Farms and ranches

Wheat-raising started slowly in Montana, replacing oats as the major grain crop only after development of new plant strains, techniques, and machinery. Wheat was stimulated by boom prices in World War I, but slumped in value and yield during the drought and depression of the next 20 years. Beginning in 1905 the Great Northern Railway in cooperation with the US Department of Agriculture, the Montana Experiment Station, and the Dryland Farming Congress promoted dryland farming in Montana in order to increase its freight traffic. During 1910-13 the Great Northern launched its own program of demonstration farms, which stimulated settlement (during 1909-10 acreage in homesteads quadrupled in Montana) through their impressive production rates for winter wheat, barley, oats and other grains[20]. As a result of the promotion the land along the Milk River in the northern tier was settled in 1900-15. In an area better suited to grazing cattle, inexperienced newcomers locally called "Honyockers" undertook to grow wheat, and met some early success when ample rainfall and high prices were the rule. For several years after 1918, droughts and hot winds destroyed the crops, bringing severe hardships and driving out all but the most determined of the settlers. Much of the land was acquired by stockmen, who have turned it back to grazing cattle[21].

By 1908, the open range that had sustained Native American tribes and government-subsidized cattle barons was pockmarked with small ranchers and a handful of straggler farmers[22]. The revised Homestead Act of the early 1900s greatly affected the settlement of Montana. This act expanded the land that was provided by the Homestead Act of 1862 from 160 acres (0.65 km2) to 320 acres (65-130 ha). When the latter act was signed by President William Taft, it also reduced the time necessary to prove up from five years to three years and permitted five months absence from the claim each year.

In 1908, the Sun River Irrigation Project, west of Great Falls was opened up for homesteading. Under this Reclamation Act, a person could obtain 40 acres (16 ha). Most of the people who came to file on these homesteads were young couples who were eager to live near the mountains where hunting and fishing were good. Many of these homesteaders came from the Midwest and Minnesota.

Cattle ranching has long been central to Montana's history and economy. The Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site in Deer Lodge Valley is maintained as a link to the ranching style of the late 19th century. It is operated by the National Park Service but is also a 1,900 acre (7.7 km²) working ranch.

Beginning in 1905 the Great Northern Railway in cooperation with the US Department of Agriculture, the Montana Experiment Station, and the Dryland Farming Congress promoted dryland farming in Montana in order to increase its freight traffic. During 1910-13 the Great Northern launched its own program of demonstration farms, which stimulated settlement (during 1909-10 acreage in homesteads quadrupled in Montana) through their impressive production rates for winter wheat, barley, and other grains[23].

Entrepreneurs

Henry Sieben (1847-1937) came to Montana's gold fields in 1864, was a farm laborer, prospector, and freighter, then turned to livestock raising along the Smith River in 1870. In partnership with his brothers he raised cattle and became one of the territory's pioneer sheep ranchers in 1875. In 1879 and Henry moved his stock to the Lewistown area. He established a reputation as an excellent businessman and as someone who took care of his stock and employees. After ranching in the Culbertson area, Henry Sieben purchased ranches near Cascade and along Little Prickly Pear Creek, forming the Sieben Livestock Company. By 1907, these two ranches had become the heart of his cattle and sheep raising business which he directed from his home in Helena. Sieben became well known for his business approach to ranching and for his public and private philanthropies. His family continues to operate the Sieben Ranch Company today[24].

After seeing the falls of the Missouri River in central Montana, Paris Gibson (1830-1920) decided the location presented an ideal site for a town. Founding Great Falls, Montana, in 1884, Gibson was inspired by a grandiose vision of an economically prosperous city that was also beautiful. He took an active role in the development of Great Falls, as well as Montana as a whole, making his voice heard on issues from dryland farming to the humane treatment of animals. While many of his visionary ideals have long since been passed by, his efforts at community building in the West serve as a unique example and provide an important perspective on the region's continuing development[25].

The Conrad families built a substantial banking business in north-central and northwestern Montana during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Banking houses at Fort Benton, Great Falls, and Kalispell, owned and managed by the families of William Conrad and Charles Conrad helped to finance Montana's economic development through an intricate pattern of familial, friendship, and business ties. Correspondent linkages to large metropolitan banks sustained the relatively small country banks by assuring them access to capital. The Conrad banks were aggressive in penetrating new lending markets and making inroads into the local farming, ranching, merchant, and manufacturing sectors. The banks grew in reputation and stature as the region developed, but remained single-unit, family-based enterprises. But Conrad's expanded across the international border into Alberta through the Conrad Circle Cattle Company[26].

Banking in Montana was a high risk business, as the 1920s demonstrated. Between 1921 and 1925 half of the state's 428 banks closed. There was an excessive number of small, weak banks in the grain-growing areas oh Eastern Montana where the postwar slump wiped out land values and related loans[27].

Marcus Daly (1841-1900), an Irish immigrant who became the statee's copper king, left a legacy of physical structures throughout Montana. Butte, with its mixture of poor miners' shacks, richly ornamented homes, mines, and mills symbolized industrial mining. At Anaconda, the company town, the great Washoe Stack poured forth pollutants that left the surrounding landscape wasted and barren. Daly's lumber mill at Bonner dominated the town. In the pastoral village of Hamilton, Daly built the 20,000-acre Bitterroot Stock Farm with its racetrack and mansion[28].

Simon Pepin (1840-1914), the "Father of Havre," was a typical Montana entrepreneur. Born in Quebec in 1840, he emigrated to Montana in 1863, and became a contractor furnishing supplies for the construction of forts Custer, Assiniboine, and Maginnis. Pepin purchased ranch lands near Fort Assiniboine. When James J. Hill built the Great Northern Railway across northern Montana, Pepin convinced him to build his locomotive shops at Havre, on property owned by Pepin. In the ensuing years, Pepin was a major contributor to Havre's economic growth through his cattle, real estate, and banking enterprises[29].

Many entrepreneurs proudly built stores, shops, and offices along Main Street. The most handsome ones used pre-formed, sheet iron facades, especially those manufactured by the Mesker Brothers of St. Louis. These neoclassical, stylized facades added sophistication to brick or woodframe buildings throughout the state[30].

Recent trends

A shift to a postmodern service economy has led to growth in smaller cities such as Missoula and Billings, while the populations and economies of larger cities, including Butte, which were founded on mining, ranching, and manufacturing, have shrunk. The eastern half of the state has lost population, as younger people move out[31]. The western third of the state has attracted tourists and up-scale part-time residents who enjoy the mountains, hunting and fishing.

Interpretations

Newspaperman and author Joseph Kinsey Howard (1906-51) believed Montana and the rural West provided the "last stand against urban technological tedium" for the individual. He fervently believed that small towns of the sort that predominated in Montana provided a democratic bulwark for society. Howard's writings demonstrate his strong belief in the necessity to identify and preserve a region's cultural heritage. His history of the state Montana: High, Wide and Handsome (1943), as well as numerous speeches and magazine articles, were based on his ideals of community awareness and identity, his hatred of the Anaconda Company, and called on readers to retain an idealistic vision contesting the deadening demands of the modern corporate world[32].

Bibliography

- Bancroft (1890). The History of Washington, Idaho and Montana (1845-1889) Vol XXXI (PDF). San Francisco, CA: The History Company.

- Judson, Katherine Berry (1912). Montana-Land of Shining Mountains. Chicago, IL: A. C. McClurg & Co.

- Stout, Tom (1921). Montana Its Story and Biography--A History of Aboriginal and Territorial Montana and Three Decade of Statehood (PDF). Chicago: American Historical Society. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- Fogarty, Kate Hammond (1916). The Story of Montana (PDF). New York: A. S. Barnes Company.

- Hedges, James B. "The Colonization Work of the Northern Pacific Railroad," Mississippi Valley Historical Review Vol. 13, No. 3 (Dec., 1926), pp. 311-342 in JSTOR

- Howard, Joseph Kinsey (1939). Montana-High, Wide and Handsome. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Malone, Michael P. (1991). Montana-A History of Two Centuries. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295971290.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

See also

- History of the Western United States

- Montana in the American Civil War

- Territorial evolution of Montana

References

- ^ "About the Crow: Migration Stories and Beginning of the Apsaalooke". Little Big Horn College Library. Retrieved 2010-01-19.

- ^ E. Adamson Hoebel, The Cheyennes: Indians of the Great Plains (1978)

- ^ William L. Bryan, Montana's Indians: Yesterday and Today (1995)

- ^ "An Act to provide a temporary Government for the Territory of Montana" (PDF). Thirty-sixth United States Congress. 1864-05-26. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- ^ Ross R. Controneo, "Northern Pacific Officials and the Disposition of the Railroad's Land Grant in North Dakota after 1888," North Dakota History, 1970, Vol. 37 Issue 2, pp 77-103

- ^ David H. Hickcox, "The Impact of the Great Northern Railway on Settlement in Northern Montana, 1880-1920," Railroad History, Summer 1983, Issue 148, pp 58-67

- ^ Robert F. Zeidel, "Peopling the Empire: The Great Northern Railroad and the Recruitment of Immigrant Settlers to North Dakota," North Dakota History, 1993, Vol. 60 Issue 2, pp 14-23

- ^ Virginia Weisel Johnson, "Tough Taft: Boom Town." Montana Dec 1982, Vol. 32 Issue 4, pp 50-57

- ^ "Livingston: Railroad Town on the Yellowstone," Montana Dec 1985, Vol. 35 Issue 4, pp 84-86

- ^ James J. Lopach, and Jean A. Luckowski. Jeannette Rankin: a political woman (2005)

- ^ Judith K. Cole, "A Wide Field for Usefulness: Women'S Civil Status and the Evolution of Women's Suffrage on The Montana Frontier, 1864-1914," American Journal of Legal History, July 1990, Vol. 34 Issue 3, pp 262-294

- ^ Stephenie Ambrose Tubbs, "Montana Women's Clubs at the Turn of the Century," Montana March 1986, Vol. 36 Issue 1, pp 26-35

- ^ Mary Melcher, "'Women's Matters': Birth Control, Prenatal Care, and Childbirth in Rural Montana, 1910-1940," Montana June 1991, Vol. 41 Issue 2, pp 47-56

- ^ Laurie K. Mercier, "Women's Role in Montana Agriculture: 'You Had To Make Every Minute Count,'" Montana Dec 1988, Vol. 38 Issue 4, pp 50-61

- ^ Laurie Mercier, Anaconda: Labor, Community, and Culture in Montana's Smelter City (University of Illinois Press, 2001)

- ^ Christine W. Brown,, "Comet, Montana: The Architecture of Abandonment," Montana Dec 2005, Vol. 55 Issue 4, pp 60-62

- ^ Laurie K. Mercier, "'The Stack Dominated Our Lives': Metals Manufacturing In Four Montana Communities," Montana June 1988, Vol. 38 Issue 2, pp 40-57

- ^ Jerry Calvert, "The Rise and Fall of Socialism in a Company Town, 1902-1905," Montana Dec 1986, Vol. 36 Issue 4, pp 2-13

- ^ Patrick C. Jobes, "A Small Rural Community Responds To Coal Development," Sociology and Social Research, Jan 1986, Vol. 70 Issue 2, pp 174-177

- ^ Claire Strom, "The Great Northern Railway and Dryland Farming in Montana," Railroad History, Summer 1997, Issue 176, pp 80-102

- ^ Mabel Lux, "Honyockers of Harlem," Montana Dec 1963, Vol. 13 Issue 4, pp 2-14

- ^ Warren M. Elofson, Frontier Cattle Ranching in the Land and Times of Charlie Russell (2005)

- ^ Claire Strom, "The Great Northern Railway and Dryland Farming in Montana," Railroad History, Summer 1997, Issue 176, pp 80-102

- ^ Dick Pace, "Henry Sieben: Pioneer Montana Stockman," Montana March 1979, Vol. 29 Issue 1, pp 2-15

- ^ Richard B. Roeder, "A Settlement on the Plains: Paris Gibson and the Building of Great Falls," Montana Dec 1992, Vol. 42 Issue 4, pp 4-19

- ^ Henry C. Klassen, "The Early Growth of the Conrad Banking Enterprise in Montana, 1880-1914," Great Plains Quarterly, Jan 1997, Vol. 17 Issue 1, pp 49-62

- ^ Clarence W. Groth, "Sowing and Reaping: Montana Banking, 1910-1925," Montana Dec 1970, Vol. 20 Issue 4, pp 28-35

- ^ Carroll Van West, "Marcus Daly and Montana: One Man's Imprint on the Land," Montana Mar 1987, Vol. 37 Issue 1, pp 60-62

- ^ Dave Walter, "Simon Pepin, A Quiet Capitalist," Montana March 1989, Vol. 39 Issue 1, pp 34-38

- ^ Arthur A. Hart, "Sheet Iron Elegance: Mail Order Architecture in Montana," Montana Dec 1990, Vol. 40 Issue 4, pp 26-31

- ^ Marvin E. Gloege, Survival or gradual extinction: the small town in the Great Plains of eastern Montana (Meadowlark Publishing Services, 2007)

- ^ Richard B. Roeder, "Joseph Kinsey Howard and his Vision of the West," Montana March 1980, Vol. 30 Issue 1, pp 2-11