Islam in the United States: Difference between revisions

→Early national period: mention novel |

→Slaves: add details and new citation |

||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

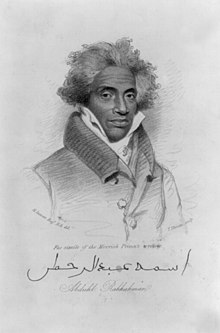

Some newly arrived Muslim slaves assembled for communal [[Salah]] (prayers). Some were provided a private praying area by their owner. The two best documented Muslim slaves were [[Ayuba Suleiman Diallo]] and [[Omar Ibn Said]]. Suleiman was brought to America in 1731 and returned to Africa in 1734.<ref name = Koszegi/> Like many Muslim slaves, he often encountered impediments when attempting to perform religious rituals and was eventually allotted a private location for prayer by his master.<ref name = Gomez1/> Omar Ibn Said (ca. 1770–1864) is among the best documented examples of a practicing-Muslim slave. He lived on a colonial North Carolina plantation and wrote many Arabic texts while enslaved. Born in the kingdom of [[Futa Tooro]] (modern [[Senegal]]), he arrived in America in 1807, one month before the US abolished importation of slaves. Some of his works include the Lords Prayer, the Bismillah, this is How You Pray, Quranic phases, the 23rd Psalm, and an autobiography. In 1857, he produced his last known writing on Surah 110 of the Quran. In 1819, Omar received an Arabic translation of the Christian Bible from his master, James Owen. Omar converted to Christianity in 1820, |

Some newly arrived Muslim slaves assembled for communal [[Salah]] (prayers). Some were provided a private praying area by their owner. The two best documented Muslim slaves were [[Ayuba Suleiman Diallo]] and [[Omar Ibn Said]]. Suleiman was brought to America in 1731 and returned to Africa in 1734.<ref name = Koszegi/> Like many Muslim slaves, he often encountered impediments when attempting to perform religious rituals and was eventually allotted a private location for prayer by his master.<ref name = Gomez1/> Omar Ibn Said (ca. 1770–1864) is among the best documented examples of a practicing-Muslim slave. He lived on a colonial North Carolina plantation and wrote many Arabic texts while enslaved. Born in the kingdom of [[Futa Tooro]] (modern [[Senegal]]), he arrived in America in 1807, one month before the US abolished importation of slaves. Some of his works include the Lords Prayer, the Bismillah, this is How You Pray, Quranic phases, the 23rd Psalm, and an autobiography. In 1857, he produced his last known writing on Surah 110 of the Quran. In 1819, Omar received an Arabic translation of the Christian Bible from his master, James Owen. Omar converted to Christianity in 1820, an episode widely used throughout the South to "prove" the benevolence of slavery. However, some scholars believe he continued to be a practicing Muslim, based on dedications to Muhammad written in his Bible<ref>Thomas C. Parramore, "Muslim Slave Aristocrats in North Carolina," ''North Carolina Historical Review,'' April 2000, Vol. 77 Issue 2, pp 127-150</ref>.<ref> In 1991, a masjid in [[Fayetteville, North Carolina]] renamed itself Masjid Omar Ibn Said in his honor. [http://library.davidson.edu/archives/ency/omars.asp Omar ibn Said] Davidson Encyclopedia Tammy Ivins, June 2007</ref> |

||

[[Peter Salem]], a former slave who fought at the [[Battle of Bunker Hill]], is speculated to have Muslim connections based on his Islamic-sounding name. Other [[American Revolution]] soldiers with Islamic names include Salem Poor, Yusuf Ben Ali, Bampett Muhamed, Francis Saba, and Joseph Saba.<ref>http://www.muslimsinamerica.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=15&Itemid=28</ref>. |

[[Peter Salem]], a former slave who fought at the [[Battle of Bunker Hill]], is speculated to have Muslim connections based on his Islamic-sounding name. Other [[American Revolution]] soldiers with Islamic names include Salem Poor, Yusuf Ben Ali, Bampett Muhamed, Francis Saba, and Joseph Saba.<ref>http://www.muslimsinamerica.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=15&Itemid=28</ref>. |

||

Revision as of 11:23, 20 August 2010

Template:Muslim American Many of the slaves brought to colonial America from Africa were Muslims, but they left a minimal impact. From the 1880s to 1914, several thousand Muslims immigrated to the United States from the Ottoman Empire, and from parts of South Asia; they did not form distinctive settlements, and probably most assimilated into the wider society [1].

The earliest documented case of a Muslim to come to the United States is Dutchman Anthony Janszoon van Salee, who came to New Amsterdam around 1630 and was referred to as 'Turk'. [2][3] The oldest Muslim community to establish in the country was the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, in 1921, which pre-dates Nation of Islam.[4][5]

Once very small, the Muslim population of the US increased greatly in the twentieth century, with much of the growth driven by rising immigration and widespread conversion.[6] In 2005, more people from Islamic countries became legal permanent United States residents — nearly 96,000 — than in any year in the previous two decades.[7][8] The new position has been created under white house executive office as a United States special envoy to the Organization of the Islamic Conference to promote relation between Islamic world and United States government.

Recent immigrant Muslims make up the majority of the total Muslim population. South Asians Muslims from India and Pakistan and Arabs make up the biggest group of Muslims in America at 60-65% of the population. Native-born American Muslims are mainly African Americans who make up a quarter of the total Muslim population. Many of these have converted to Islam during the last seventy years. Conversion to Islam in prison,[9] and in large urban areas[10] has also contributed to its growth over the years. American Muslims come from various backgrounds, and are one of the most racially diverse religious group in the United States according to a 2009 Gallup poll.[11]

A Pew report released in 2009 noted that nearly six-in-ten American adults see Muslims as being subject to discrimination, more than Mormons, Atheists, or Jews.[12]

History

The history of Islam in the United States can be divided into two significant periods: the post World War I period, and the last few decades. Although some individual members of the Islamic faith are known to have visited or lived in the United States during the colonial era.[13]

Islam in the early United States

Estevanico of Azamor may have been the first Muslim to enter the historical record in North America. Estevanico was a Berber originally from North Africa who explored the future states of Arizona and New Mexico for the Spanish Empire..[14][15]

Early national period

American views of Islam affected debates regarding freedom of religion during the drafting of the state constitution of Pennsylvania in 1776. Constitutionalists promoted religious toleration while Anticonstitutionalists called for reliance on Protestant values in the formation of the state's republican government. The former group won out, and inserted a clause for religious liberty in the new state constitution. American views of Islam were influenced by favorable Enlightenment writings from Europe, as well as Europeans who had long warned that Islam was a threat to Christianity and republicanism[16].

A common rhetoric technique was to identify an argument with Muslims, thereby discrediting it. Benjamin Franklin attacked slavery by writing a fictional defense of it by a Muslim.

Between 1785 and 1815, over a hundred American sailors were captive in Algiers for ransom. Several wrote captivity narratives of their experiences that gave most Americans their first view of the Middle East and Muslim ways, and newspapers often commented on them. The result was a collage of misinformation and ugly stereotypes. Royall Tyler wrote The Algerine Captive (1797), an early American novel depicting the life of an American doctor employed in the slave trade who becomes himself enslaved by Barbary pirates. Finally Washington sent in the Navy to confront the pirates, and ended the threat in 1815[17][18][19].

Religious freedom

In 1776, John Adams published "Thoughts on Government," in which he praises the Islamic prophet Mahomet (Mohammed) as a "sober inquirer after truth" alongside Confucius, Zoroaster, Socrates, and other "pagan and Christian" thinkers.

In 1785, George Washington stated a willingness to hire "Mahometans," as well as people of any nation or religion, to work on his private estate at Mount Vernon if they were "good workmen."[20]

In 1790, the South Carolina legislative body granted special legal status to a community of Moroccans, twelve years after the Sultan of Morocco became the first foreign head of state to formally recognize the United States.[21] In 1796, then president John Adams signed a treaty declaring the United States had no "character of enmity against the laws, religion, or tranquillity, of Mussulmen".[22]

In his autobiography, published in 1791, Benjamin Franklin stated that he "did not disapprove" of a meeting place in Pennsylvania that was designed to accommodate preachers of all religions. Franklin wrote that "even if the Mufti of Constantinople were to send a missionary to preach Mohammedanism to us, he would find a pulpit at his service."[23]

Thomas Jefferson defended religious freedom in America including those of Muslims. Jefferson explicitly mentioned Muslims when writing about the movement for religious freedom in Virginia. In his autobiography Jefferson wrote "[When] the [Virginia] bill for establishing religious freedom... was finally passed,... a singular proposition proved that its protection of opinion was meant to be universal. Where the preamble declares that coercion is a departure from the plan of the holy author of our religion, an amendment was proposed, by inserting the word 'Jesus Christ,' so that it should read 'a departure from the plan of Jesus Christ, the holy author of our religion.' The insertion was rejected by a great majority, in proof that they meant to comprehend within the mantle of its protection the Jew and the Gentile, the Christian and Mahometan, the Hindoo and infidel of every denomination."[24] While President, Jefferson also participated in an iftar with the Ambassador of Tunisia in 1809.[25]

19th century

Alexander Russell Webb is considered by historians to be the earliest prominent Anglo-American convert to Islam in 1888. In 1893 he was the only person representing Islam at the first Parliament for the World's Religions.[26]

Slaves

Many of the slaves brought to colonial America from Africa were Muslims[27][28]. By 1800, some 500,000 Africans arrived in what became the United States. Historians estimate that between 15 to 30 percent of all enslaved African men, and less than 15 percent of the enslaved African women, were Muslims. These enslaved Muslims stood out from their compatriots because of their "resistance, determination and education" [29] It is estimated that over 50% of the slaves imported to North America came from areas where Islam was followed by at least a minority population. Thus, no less than 200,000 came from regions influenced by Islam. Substantial numbers originated from Senegambia, a region with an established community of Muslim inhabitants extending to the 11th century.[30] Michael A. Gomez speculated that Muslim slaves may have accounted for "thousands, if not tens of thousands," but does not offer a precise estimate. He also suggests many non-Muslim slaves were acquainted with some tenets of Islam, due to Muslim trading and proselytizing activities.[31] Historical records indicate many enslaved Muslims conversed in the Arabic language. Some even composed literature (such as autobiographies) and commentaries on the Quran.[32]

Some newly arrived Muslim slaves assembled for communal Salah (prayers). Some were provided a private praying area by their owner. The two best documented Muslim slaves were Ayuba Suleiman Diallo and Omar Ibn Said. Suleiman was brought to America in 1731 and returned to Africa in 1734.[30] Like many Muslim slaves, he often encountered impediments when attempting to perform religious rituals and was eventually allotted a private location for prayer by his master.[32] Omar Ibn Said (ca. 1770–1864) is among the best documented examples of a practicing-Muslim slave. He lived on a colonial North Carolina plantation and wrote many Arabic texts while enslaved. Born in the kingdom of Futa Tooro (modern Senegal), he arrived in America in 1807, one month before the US abolished importation of slaves. Some of his works include the Lords Prayer, the Bismillah, this is How You Pray, Quranic phases, the 23rd Psalm, and an autobiography. In 1857, he produced his last known writing on Surah 110 of the Quran. In 1819, Omar received an Arabic translation of the Christian Bible from his master, James Owen. Omar converted to Christianity in 1820, an episode widely used throughout the South to "prove" the benevolence of slavery. However, some scholars believe he continued to be a practicing Muslim, based on dedications to Muhammad written in his Bible[33].[34]

Peter Salem, a former slave who fought at the Battle of Bunker Hill, is speculated to have Muslim connections based on his Islamic-sounding name. Other American Revolution soldiers with Islamic names include Salem Poor, Yusuf Ben Ali, Bampett Muhamed, Francis Saba, and Joseph Saba.[35].

Bilali (Ben Ali) Muhammad was a Fula Muslim from Timbo Futa-Jallon in present day Guinea-Conakry, who arrived to Sapelo Island during 1803. While enslaved, he became the religious leader and Imam for a slave community numbering approximately eighty Muslim men residing on his plantation. He is known to have fasted during the month of Ramadan, worn a fez and kaftan, and observed the Muslim feasts, in addition to consistently performing the five obligatory prayers.[36] In 1829, Bilali authored a thirteen page Arabic Risala on Islamic law and conduct. Known as the Bilali Document, it is currently housed at the University of Georgia in Athens.

Modern immigration

Small-scale migration to the U.S. by Muslims began in 1840, with the arrival of Yemenites and Turks,[30] and lasted until World War I. Most of the immigrants, from Arab areas of the Ottoman Empire, came with the purpose of making money and returning to their homeland. However, the economic hardships of 19th-Century America prevented them from prospering, and as a result the immigrants settled in the United States permanently. These immigrants settled primarily in Dearborn, Michigan; Quincy, Massachusetts; and Ross, North Dakota. Ross, North Dakota is the site of the first documented mosque and Muslim Cemetery, but it was abandoned and later torn down in the mid 1970s. A new mosque was built in its place in 2005.[26]

- 1906 Bosnian Muslims in Chicago, Illinois started the Jamaat al-Hajrije (Assembly Society; a social service organization devoted to Bosnian Muslims). This is the longest lasting incorporated Muslim community in the United States. They met in coffeehouses and eventually opened the first Islamic Sunday School with curriculum and textbooks under Imam Kamil Avdih (a graduate of al-Azhar and author of Survey of Islamic Doctrines).

- 1907 Lipka Tatar immigrants from the Podlasie region of Poland founded the first Muslim organization in New York City, the American Mohammedan Society[37] .

- 1915, what is most likely the first American mosque was founded by Albanian Muslims in Biddeford, Maine. A Muslim cemetery still exists there.[38][39]

- 1920 First Islamic mission station was established by an Indian Ahmadiyya Muslim missionary, followed by the building of the Al-Sadiq Mosque in 1921.

- 1934 The first building built specifically to be a mosque is established in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

- 1945 A mosque existed in Dearborn, Michigan, home to the largest Arab-American population in the U.S.

Construction of mosques sped up in the 1920s and 1930s, and by 1952, there were over 20 mosques.[26] Although the first mosque was established in the U.S. in 1915, relatively few mosques were founded before the 1960s. Eighty-seven percent of mosques in the U.S. were founded within the last three decades according to the Faith Communities Today (FACT) survey. California has more mosques than any other state.

Chinese Muslims have immigrated to the United States and lived within the Chinese community rather than integrating into other foreign Muslim communities. Two of the most prominent Chinese American Muslims are the Republic of China National Revolutionary Army Generals Ma Hongkui and his son Ma Dunjing who moved to Los Angeles in California after fleeing from China to Taiwan. Pai Hsien-yung is another Chinese Muslim writer who moved to Santa Barbara in California the United States after fleeing from China to Taiwan, his father was the Chinese Muslim General Bai Chongxi.

Black Muslim movements

During the first half of the 20th century few numbers of African Americans established groups based on Islamic and Black supremacist teachings.[40] The first of such groups created was the Moorish Science Temple of America, founded by Timothy Drew (Drew Ali) in 1913. Drew taught that Black people were of Moorish origin but their Muslim identity was taken away through slavery and racial segregation, advocating the return to Islam of their Moorish ancestry.[41] The Nation of Islam (NOI) was the largest organization, created in 1930 by Wallace Fard Muhammad. It however taught a different form of Islam, promoting Black supremacy and labeling white people as "devils".[42] Fard drew inspiration for NOI doctrines from those of Noble Drew Ali's Moorish Science Temple of America. He provided three main principles which serve as the foundation of the NOI: "Allah is God, the white man is the devil and the so called Negroes are the Asiatic Black People, the cream of the planet earth". In 1934 Elijah Muhammad became the leader of the NOI, he deified Wallace Fard, saying that he was an incarnation of God, and taught that he was a prophet who had been taught directly by God in the form of Wallace Fard. Although Elijah's message caused great concern among White Americans, it was effective among Blacks attracting mainly poor people including students and professionals. One of the famous people to join the NOI was Malcolm X, who was the face of the NOI in the media. Also boxing world champion, Muhammad Ali.[40]

After the death of Elijah Muhammad, he was succeeded by his son, Warith Deen Mohammed. Mohammed rejected many teachings of his father, such as the divinity of Fard Muhammad and saw a white person as also a worshipper. As he took control of the organization, he quickly brought in new reforms.[43] He renamed it as the World Community of al-Islam in the West, later it became the American Society of Muslims. It was estimated that there were 200,000 followers of WD Mohammed at the time.[44] He introduced teachings which were based on orthodox Sunni Islam.[45] He removed the chairs in temples, with mosques, teaching how to pray the salah, to observe the fasting of Ramadan, and to attend the pilgrimage to Mecca.[46] It was the largest mass religious conversion in the 21st century, with thousands who had converted to orthodox Islam.

A few number of Black Muslims however rejected these new reforms brought by Imam Mohammed, Louis Farrakhan who broke away from the organization, re-established the Nation of Islam under the original Fardian doctrines, and remains its leader.[47] As of today it is estimated there are at least 20,000 members.[48] However, today the group has a wide influence in the African American community. The Million Man March in 1994 remains the largest organized march in Washington, D.C.[49] The group sponsors cultural and academic education, economic independence, and personal and social responsibility. The Nation of Islam has received a great deal of criticism for its anti-white, anti-Christian, and anti-semitic teachings,[50] and is listed as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center.[51]

Demographics

| Muslim population estimates | |

|---|---|

| American Religious Identification Survey | 1.3 million (2008)[52] |

| Pew Research Center | 2.5 million (2009)[53] |

| Encyclopædia Britannica | 4.7 million (2004)[54] |

| U.S. News & World Report | 5 million+ (2008)[55] |

| Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) | 7 million (2010)[56] |

There is no accurate count of the number of Muslims in the United States, as the U.S. Census Bureau does not collect data on religious identification. There is an ongoing debate as to the true size of the Muslim population in the US. Various institutions and organizations have given widely varying estimates about how many Muslims live in the U.S. These estimates have been controversial, with a number of researchers being explicitly critical of the survey methodologies that have led to the higher estimates.[57] Others claim that no scientific count of Muslims in the U.S. has been done, but that the larger figures should be considered accurate.[58] Some journalists have also alleged that the higher numbers have been inflated for political purposes.[59] On the other hand, some Muslim groups blame Islamophobia and the fact that many Muslims identify themselves as Muslims, but do not attend mosques for the lower estimates.[60]

According to a 2007 religious survey, 72% of Muslims believe religion is very important, which is higher in comparison to the overall population of the United States at 59%. The frequency of receiving answers to prayers among Muslims was, 31% at least once a week and 12% once or twice a month.[61] Nearly a quarter of the Muslims are converts to Islam (23%), mainly native-born. Of the total who have converted, 59% are African American and 34% white. Previous religions of those converted was Protestantism (67%), Roman Catholicism (10%) and 15% no religion.

Mosques are usually explicitly Sunni or Shia. There are 1,209 mosques in the United States and the nation's largest mosque, the Islamic Center of America, is in Dearborn, Michigan. It was rebuilt in 2005 to accommodate over 3,000 people for the increasing Muslim population in the region.[62][63] In many areas, a mosque may be dominated by whatever group of immigrants is the largest. Sometimes the Friday sermons, or khutbas, are given in languages like Urdu or Arabic along with English. Areas with large Muslim populations may support a number of mosques serving different immigrant groups or varieties of belief within Sunni or Shi'a traditions. At present, many mosques are served by imams who immigrate from overseas, as only these imams have certificates from Muslim seminaries. This sometimes leads to conflict between the congregation and an imam who speaks little English and has little understanding of American culture. Some American Muslims have founded seminaries in the US in an attempt to prevent such problems.[64] The influence of the Wahhabi movement in the US has caused concern.[65][66][67]

Muslim Americans are racially diverse communities in the United States, two-thirds are foreign-born.[68] The majority, about three-fifths of Muslim Americans are of South Asian and Arab origin, a quarter of the population are indigenous African Americans, while the remaining are other ethnic groups which includes Turks, Iranians, Bosnians, Malays, Indonesians, West Africans, Somalis, Kenyans, with also small but growing numbers of white and Hispanic converts.[69] A survey of ethnic comprehension by the Pew Forum survey in 2007 showed that 37% respondents viewed themselves of white descent (mainly of Arab and South Asian origin), 24% were Black (mainly African American), 20% Asian (mainly South Asian origin), 15% other race (includes mixed Arabs or Asians) and 4% were of Hispanic descent.[68] Since the arrival of South Asian and Arab communities during the 1990s there has been divisions with the African Americans due to the racial and cultural differences, however since post 9/11, the two groups joined together when the immigrant communities looked towards the African Americans for advice on civil rights.[70] Approximately half (50%) of the religious affiliations of Muslims is Sunni, 16% Shia, 22% non-affiliated and 16% other/non-response.[68] Muslims of Arab descent are mostly Sunni (56%) with minorities who are Shia (19%). Pakistanis (62%) and Indians (82%) are mainly Sunni, while Iranians are mainly Shia (91%).[68] Of African American Muslims, 48% are Sunni, 34% are unaffiliated, 2% Shia, the remaining are others.[68]

In 2005, according to the New York Times, more people from Muslim countries became legal permanent United States residents — nearly 96,000 — than in any year in the previous two decades.[7][8][71] In addition to immigration, the state, federal and local prisons of the United States may be a contributor to the growth of Islam in the country. J. Michael Waller claims that Muslim inmates comprise 17-20% of the prison population, or roughly 350,000 inmates in 2003. He also claims that 80% of the prisoners who "find faith" while in prison convert to Islam.[72] These converted inmates are mostly African American, with a small but growing Hispanic minority. Waller also asserts that many converts are radicalized by outside Islamist groups linked to terrorism, but other experts suggest that when radicalization does occur it has little to no connection with these outside interests.[73][74][75]

Culture

Muslims in the United States have increasingly contributed to American culture; there are various Muslim comedy groups, rap groups, Scout troops and magazines, and Muslims have been vocal in other forms of media as well.[76]

Within the Muslim community in the United States there exist a number of different traditions. As in the rest of the world, the Sunni Muslims are in the majority. Shia Muslims, especially those in the Iranian immigrant community, are also active in community affairs. All four major schools of Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) are found among the Sunni community. Some Muslims in the U.S. are also adherents of certain global movements within Islam such as the Salafi/Wahabi, the Muslim Brotherhood, the Gulen Movement, and the Tablighi Jamaat, as well as movements which are not considered by some muslims as part of mainstream Islam, such as the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community or Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement or Louis Farrakhan's Nation of Islam.

Integration

According to a 2004 telephone survey of a sample of 1846 Muslims conducted by the polling organization Zogby, the respondents were more educated and affluent than the national average, with 59% of them holding at least an undergraduate college degree.[77] Citing the Zogby survey, a 2005 Wall Street Journal editorial by Bret Stephens and Joseph Rago expressed the tendency of American Muslims to report employment in professional fields, with one in three having an income over $75,000 a year.[78] The editorial also characterized American Muslims as "role models both as Americans and as Muslims".

Unlike many Muslims in Europe, American Muslims do not tend to feel marginalized or isolated from political participation. Several organizations were formed by the American Muslim community to serve as 'critical consultants' on U.S. policy regarding Iraq and Afghanistan. Other groups have worked with law enforcement agencies to point out Muslims within the United States that they suspect of fostering 'intolerant attitudes'. Still others have worked to invite interfaith dialogue and improved relations between Muslim and non-Muslim Americans.[79]

Growing Muslim populations have caused public agencies to adapt to their religious practices. Airports such as the Indianapolis International Airport, Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport[80] as well as the Kansas City International Airport have installed foot-baths to allow Muslims, particularly taxicab drivers who service the airports, to perform their religious ablutions in a safe and sanitary manner.[81] In addition, Denver International Airport included a masjid as part of its Interfaith Chapel when opened in 1996.[82]

As of May 30, 2005, over 15,000 Muslims were serving in the United States Armed Forces[83].

Organizations

The are many Islamic organisations which most mosques have an association with, the largest group is the Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) which 27% of mosques are affiliated with it.[84] ISNA is an association of immigrant Muslim organizations and individuals that provides a common platform for presenting Islam. It is composed mostly of immigrants. Its membership may have recently exceeded ASM, as many independent mosques throughout the United States are choosing to affiliate with it. ISNA's annual convention is the largest gathering of Muslims in the United States.[85]

The second largest is the community under the leadership of W.Deen Mohammed or the American Society of Muslims with 19% of mosques having an affiliation with it.[84] It was the successor organization to the Nation of Islam, once better-known as the Black Muslims. The association recognises under the leadership of Warith Deen Mohammed. This group evolved from the Black separatist Nation of Islam (1930–1975). The majority of its members are African Americans. This has been a twenty-three year process of religious reorientation and organizational decentralization, in the course of which the group was known by other names, such as the American Muslim Mission, W.Deen Mohammed guided its members to the practice of mainstream Islam such as salah or fasting, and teaching the basic creed of Islam the shahadah.

The third largest group is the Islamic Circle of North America (ICNA). ICNA describes itself as a non-ethnic, open to all, independent, North America-wide, grass-roots organization. It is composed mostly of immigrants and the children of immigrants. It is growing as various independent mosques throughout the United States join and also may be larger than ASM at the present moment. Its youth division is Young Muslims.[86]

The Islamic Supreme Council of America (ISCA) represents a few Muslims. Its stated aims include providing practical solutions for American Muslims, based on the traditional Islamic legal rulings of an international advisory board, many of whom are recognized as the highest ranking Islamic scholars in the world. ISCA strives to integrate traditional scholarship in resolving contemporary issues affecting the maintenance of Islamic beliefs in a modern, secular society.[87] It has been linked to neoconservative thought.

The Islamic Assembly of North America (IANA) is a leading Muslim organization in the United States. According to its website, among the goals of IANA is to "unify and coordinate the efforts of the different dawah oriented organizations in North America and guide or direct the Muslims of this land to adhere to the proper Islamic methodology." In order to achieve its goals, IANA uses a number of means and methods including conventions, general meetings, dawah-oriented institutions and academies, etc.[88] IANA folded in the aftermath of the attack of September 11, 2001 and they have reorganized under various banners such as Texas Dawah and the Almaghrib Institute

The Muslim Students' Association (MSA) is a group dedicated, by its own description, to Islamic societies on college campuses in Canada and the United States for the good of Muslim students. The MSA is involved in providing Muslims on various campuses the opportunity to practice their religion and to ease and facilitate such activities. MSA is also involved in social activities, such as fund raisers for the homeless during Ramadan. The founders of MSA would later establish the Islamic Society of North America and Islamic Circle of North America.[89]

The Islamic Information Center (IIC) (IIC) is a "grass-roots" organization that has been formed for the purpose of informing the public, mainly through the media, about the real image of Islam and Muslims. The IIC is run by chairman (Hojatul-Islam) Imam Syed Rafiq Naqvi, various committees, and supported by volunteers.[90]

Ahmadiyya Muslim Community is the oldest Muslim community to establish in the country in 1921, pre-dating Nation of Islam.

Political

Muslim political organizations lobby on behalf of various Muslim political interests. Organizations such as the American Muslim Council are actively engaged in upholding human and civil rights for all Americans.

- The Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) is the United States largest Muslim civil rights and advocacy group, originally established to promote a positive image of Islam and Muslims in America. CAIR portrays itself as the voice of mainstream, moderate Islam on Capitol Hill and in political arenas throughout the United States. It has condemned acts of terrorism - while naming no one in particular - and has been working in collaboration with the White House on "issues of safety and foreign policy."[79] The group has been criticized for alleged links to Islamic terrorism by conservative media, but its leadership strenuously denies any involvement with such activities.

- The Muslim Public Affairs Council (MPAC) is an American Muslim public service & policy organization headquartered in Los Angeles and with offices in Washington, D.C. MPAC was founded in 1988. The mission of MPAC "encompasses promoting an American Muslim identity, fostering an effective grassroots organization, and training a future generation of men and women to share our vision. MPAC also works to promote an accurate portrayal of Islam and Muslims in mass media and popular culture, educating the American public (both Muslim and non-Muslim) about Islam, building alliances with diverse communities and cultivating relationships with opinion- and decision-makers."[91]

- The American Islamic Congress is a small but growing moderate Muslim organization that promotes religious pluralism. Their official Statement of Principles states that "Muslims have been profoundly influenced by their encounter with America. American Muslims are a minority group, largely comprising immigrants and children of immigrants, who have prospered in America's climate of religious tolerance and civil rights. The lessons of our unprecedented experience of acceptance and success must be carefully considered by our community."[92]

- The Free Muslims Coalition was created to eliminate broad base support for Islamic extremism and terrorism and to strengthen secular democratic institutions in the Middle East and the Muslim World by supporting Islamic reformation efforts.[93]

Charity

In addition to the organizations just listed, other Muslim organizations in the United States serve more specific needs. For example, some organizations focus almost exclusively on charity work. As a response to a crackdown on Muslim charity organizations working overseas such as the Holy Land Foundation, more Muslims have begun to focus their charity efforts within the United States.

- Inner-City Muslim Action Network (IMAN) is one of the leading Muslim charity organizations in the United States. According to the Inner-City Muslim Action Network, IMAN seeks "to utilize the tremendous possibilities and opportunities that are present in the community to build a dynamic and vibrant alternative to the difficult conditions of inner city life." IMAN sees understanding Islam as part of a larger process to empower individuals and communities to work for the betterment of humanity.[94]

- Islamic Relief USA is the American branch of Islamic Relief Worldwide, an international relief and development organization. Their stated goal is "to alleviate the suffering, hunger, illiteracy and diseases worldwide without regard to color, race or creed." They focus of development projects; emergency relief projects, such as providing aid to victims of Hurricane Katrina; orphans projects; and seasonal projects, such as food distributions during the month of Ramadan. They provide aid internationally and in the United States.[95]

Views of America and Islam

American populace's views on Islam

A nationwide survey conducted in 2003 by the Pew Research Center and the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life reported that the percentage of Americans with an unfavorable view of Islam increased by one percentage point between 2002 and 2003 to 34%, and then by another two percentage points in 2005 to 36%. At the same time the percentage responding that Islam was more likely than other religion to encourage violence fell from 44% in July 2003 to 36% in July 2005.[96]

| July 2007 Newsweek survey of non-Muslim Americans[97] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Statement | Agree | Disagree |

| Muslims in the United States are as loyal to the U.S. as they are to Islam |

40% | 32% |

| Muslims do not condone violence | 63% | |

| Qur'an does not condone violence | 40% | 28% |

| Muslim culture does not glorify suicide |

41% | |

| Concern about Islamic radicals | 54% | |

| Support wiretapping by FBI | 52% | |

| American Muslims more "peaceable" than non-American ones |

52% | 7% |

| Muslims are unfairly targeted by law enforcement |

38% | 52% |

| Oppose mass detentions of Muslims | 60% | 25% |

| Believe most are immigrants | 52% | |

| Would allow son or daughter to date a Muslim |

64% | |

| Muslim students should be allowed to wear headscarves |

69% | 23% |

| Would vote for a qualified Muslim for political office |

45% | 45% |

The July 2005 Pew survey also showed that 59% of American adults view Islam as "very different from their religion," down one percentage point from 2003. In the same survey 55% had a favorable opinion of Muslim Americans, up four percentage points from 51% in July 2003.[96] A December 2004 Cornell University survey shows that 47% of Americans believe that the Islamic religion is more likely than others to encourage violence among its believers.[98]

A CBS April 2006 poll showed that, in terms of faiths[99]

- 58% of Americans have favorable attitudes toward Protestantism/Other Christians

- 48% favorable toward Catholicism

- 47% favorable toward Judaism

- 31% favorable toward Christian fundamentalism

- 20% favorable toward Mormonism

- 19% favorable toward Islam

- 8% favorable toward Scientology

The Pew survey shows that, in terms of adherents[96]

- 77% of Americans have favorable opinions of Jews

- 73% favorable of Catholics

- 57% favorable of "evangelical Christians"

- 55% favorable of Muslims

- 35% favorable of Atheists

American Muslims' views of the United States

| PEW's poll of views on American Society[100] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Statement | U.S. Muslim |

General public |

| Agree that one can get ahead with hard work |

71% | 64% |

| Rate their community as "excellent" or "good" |

72% | 82% |

| Excellent or good personal financial situation |

42% | 49% |

| Satisfied with the state of the U.S. |

38% | 32% |

In a 2007 survey titled Muslim Americans: Middle Class and Mostly Mainstream, the Pew Research Center found Muslim Americans to be

largely assimilated, happy with their lives, and moderate with respect to many of the issues that have divided Muslims and Westerners around the world.[100]

47% of respondents said they considered themselves Muslims first and Americans second. However, this was compared to 81% of British Muslims and 69% of German Muslims, when asked the equivalent question. A similar disparity exists in income, the percentage of American Muslims living in poverty is 2% higher than the general population, compared to an 18% disparity for French Muslims and 29% difference for Spanish Muslims.[100]

Politically, American Muslims were both pro-larger government and socially conservative. For example, 70% of respondents preferred a bigger government providing more services, while 61% stated that homosexuality should be discouraged by society. Despite their social conservatism, 71% of American Muslims expressed a preference for the Democratic Party.[100] The Pew Research survey also showed that nearly three quarters of respondents believed that American society rewards them for hard work regardless of their religious background [101].

The same poll also reported that only 40 percent of U.S. Muslims believe that Arabs carried out the 9/11 attacks. Another 28 percent don't believe it and 32 percent said they had no view. Among 28 percent who doubted that Arabs were behind the conspiracy, one-fourth of those claim the U.S. government or President George W. Bush was responsible. Only 26 percent of American Muslims believe the U.S.-led war on terror is a sincere effort to root out international terrorism. Only 5% of those surveyed had a "very favorable" or "somewhat favorable" view of the terrorist group Al-Qaeda. Only 35% of American Muslims stated that the decision for military action in Afghanistan was the right one and just 12% supported the use of military force in Iraq.[100]

American Muslim life after the September 11, 2001 attacks

After the September 11, 2001 attacks, there were occasional attacks on some Muslims living in the U.S., although this was restricted to a small minority.[102][103]

In a 2007 survey, 53% of American Muslims reported that it was more difficult to be a Muslim after the 9/11 attacks. Asked to name the most important problem facing them, the options named by more than ten percent of American Muslims were discrimination (19%), being viewed as a terrorist (15%), public's ignorance about Islam (13%), and stereotyping (12%). 54% believe that the U.S. government's anti-terrorism activities single out Muslims. 76% of surveyed Muslim Americans stated that they are very or somewhat concerned about the rise of Islamic extremism around the world, while 61% express a similar concern about the possibility of Islamic extremism in the United States.[100]

On a small number of occasions Muslim women who wore distinctive hijab were harassed, causing some Muslim women to stay at home, while others temporarily abandoned the practice. In 2006, one California woman was shot dead as she walked her child to school; she was wearing a headscarf and relatives and Muslim leaders believe that the killing was religiously motivated.[102][103] While 51% of American Muslims express worry that women wearing hijab will be treated poorly, 44% of American Muslim women who always wear hijab express a similar concern.[100]

Controversy

Some Muslim Americans have been criticized for letting their religious beliefs affect their ability to act within mainstream American value systems. Muslim cab drivers in Minneapolis, Minnesota have been criticized for refusing passengers for carrying alcoholic beverages or dogs, including disabled passengers with guide dogs. The Minneapolis-Saint Paul International Airport authority has threatened to revoke the operating authority of any driver caught discriminating in this manner.[104] There are reported incidents in which Muslim cashiers have refused to sell pork products to their clientèle.[105]

Public institutions in the U.S. have also been criticized for accommodating Islam at the expense of taxpayers. The University of Michigan–Dearborn and a public college in Minnesota have been criticized for accommodating Islamic prayer rituals by constructing footbaths for Muslim students using tax-payers' money. Critics claim this special accommodation, which is made only to satisfy Muslims' needs, is a violation of Constitutional provisions separating church and state.[106] Along the same constitutional lines, a San Diego public elementary school is being criticized for making special accommodations specifically for American Muslims by adding Arabic to its curriculum and giving breaks for Muslim prayers. Since these exceptions have not been made for any religious group in the past, some critics see this as an endorsement of Islam.[107]

The first American Muslim Congressman, Keith Ellison, created controversy when he compared President George W. Bush's actions after the September 11, 2001 attacks to Adolf Hitler's actions after the Nazi-sparked Reichstag fire, saying that Bush was exploiting the aftermath of 9/11 for political gain, as Hitler had exploited the Reichstag fire to suspend constitutional liberties.[108] The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and the Anti-Defamation League condemned Ellison's remarks. The congressman later retracted the statement, saying that it was "inappropriate" for him to have made the comparison.[109]

At Columbus Manor School, a suburban Chicago elementary school with a student body nearly half Arab American, school board officials have considered eliminating holiday celebrations after Muslim parents complained that their culture's holidays were not included. Local parent Elizabeth Zahdan said broader inclusion, not elimination, was the group's goal. "I only wanted them modified to represent everyone," the Chicago Sun-Times quoted her as saying. "Now the kids are not being educated about other people."[110] However, the district's superintendent, Tom Smyth, said too much school time was being taken to celebrate holidays already, and he sent a directive to his principals requesting that they "tone down" activities unrelated to the curriculum, such as holiday parties.

The 2007 Pew poll reported that 15% of American Muslims under the age of 30 supported suicide bombings against civilian targets in at least some circumstances, while a further 11 percent said it could be "rarely justified." Among those over the age of 30, just 6% expressed their support for the same. (9% of Muslims over 30 and 5% under 30 chose not to answer). Only 5% of American Muslims had a favorable view of al-Qaeda.[100]

Disaffected Muslims in the U.S.

Some Muslims in the U.S. have adopted the strong anti-American opinions common in many Muslim-majority countries.[citation needed] In some cases, these are recent immigrants who have carried their anti-American sentiments with them. The Egyptian cleric, Omar Abdel-Rahman is now serving a jail sentence for his involvement in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. He had a long history of involvement with Islamist and jihadi groups before arriving in the US.

There is an openly anti-American Muslim group in the U.S. The Islamic Thinkers Society [5], found only in New York City, engages in leafleting and picketing to spread their viewpoint.

Young, immigrant Muslims feel more frustrated and exposed to prejudice than their parents are. Because most U.S. Muslims are raised conservatively, and won't consider rebelling through sex or drugs, many experiment with their faith shows a poll, dated June 7, 2007. [6]

At least one non-immigrant American, John Walker Lindh, has also been imprisoned or convicted on charges of serving in the Taliban army and carrying weapons against U.S. soldiers. He had converted to Islam in the U.S., moved to Yemen to study Arabic, and thence went to Pakistan where he was recruited by the Taliban.

Other notable cases include:

- The Buffalo Six: Shafal Mosed, Yahya Goba, Sahim Alwan, Mukhtar Al-Bakri, Yasein Taher, Elbaneh Jaber. Six Muslims from the Lackawanna, N.Y. area were charged and convicted for providing material support to al Qaeda.[111]

- Iyman Faris In October 2003 Iyman Faris was sentenced to 20 years in prison for providing material support and resources to al Qaeda and conspiracy for providing the terrorist organization with information about possible U.S. targets for attack.[111]

- Ahmed Omar Abu Ali In November 2005 he was convicted and sentenced to 30 years in prison for providing material support and resources to al Qaeda, conspiracy to assassinate the President of the United States, conspiracy to commit air piracy and conspiracy to destroy aircraft.[111]

- Ali al-Tamimi was convicted and sentenced in April 2005 to life in prison for recruiting Muslims in the US to fight U.S. troops in Afghanistan.[111]

Criticism of Islam in the United States

- Daniel Pipes, Steven Emerson and Robert Spencer have suggested that a segment of the U.S. Muslim population exhibit hate and a wish for violence towards the United States.[112][113][114]

- Muslim convert journalist Stephen Schwartz, American Jewish Committee terrorism expert Yehudit Barsky, and U.S. Senator Chuck Schumer have all separately testified to a growing radical Islamist Wahhabi influence in U.S. mosques, financed by extremist groups. According to Barsky, 80% of U.S. mosques are so radicalized.[115][116][117] In an effort to address this extremist influence, ISNA has implemented assorted programs and guidelines in order to help mosques identify and counter any such individuals.[118]

Responses to criticism

- Peter Bergen says that Islamism is adopted by a minority of U.S. Muslims, saying that a "vast majority of American Muslims have totally rejected the Islamist ideology of Osama bin Laden".[119]

- International Institute of Islamic Thought Director of Research Louay M. Safi has questioned the motives of several noted critics, alleging that members of what he terms the "extreme right" are exploiting security concerns to further various Islamophobic objectives.[120]

- A 1998 United Nations report on "Civil and Political Rights, including Freedom of Expression" in the United States sharply criticised the attitude of the American media, noting "very harmful activity by the media in general and the popular press in particular, which consists in putting out a distorted and indeed hate-filled message treating Muslims as extremists and terrorists", adding that "efforts to combat the ignorance and intolerance purveyed by the media, above all through preventive measures in the field of education, should be given priority."[121]

See also

- Islam in Latin America

- Islamophobia

- Diaspora studies

- Hyphenated American

- Islam in the African diaspora

- Latino Muslims

- List of American Muslims

- List of mosques in the United States

- List of Islamic and Muslim related topics

- Timeline of Muslim history

- Western Muslims

- Islam and Protestantism

- Honor killing in the United States

Further reading

- Curtis IV, Edward E. Muslims in America: A Short History (2009)

- GhaneaBassiri, Kambiz. A History of Islam in America: From the New World to the New World Order (Cambridge University Press; 2010) 416 pages; chronicles the Muslim presence in America across five centuries.

- Haddad, Yvonne Yazbeck, Jane I. Smith, and Kathleen M. Moore. Muslim Women in America: The Challenge of Islamic Identity Today (2006)

- Kidd, Thomas. S. American Christians and Islam - Evangelical Culture and Muslims from the Colonial Period to the Age of Terrorism, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2008 ISBN 9780691133492

- Koszegi, Michael A., and J. Gordon Melton, eds. Islam In North America (Garland Reference Library of Social Science) (1992)

- Marable, Manning; Aidi, Hishaam D, eds. (2009). Black Routes to Islam. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-8400-X.

- Smith, Jane I; Islam in America (2nd ed. 2009)

Notes

- ^ Curtis, Muslims in America, p 119

- ^ Shorto, Russell, 2004. The Island at the Centre of the World.

- ^ De Valdez y Cocom, Mario. The Van Salee Family [1]

- ^ Official site

- ^ reference at end

- ^ A NATION CHALLENGED: AMERICAN MUSLIMS; Islam Attracts Converts By the Thousand, Drawn Before and After Attacks

- ^ a b Muslim immigration has bounced back

- ^ a b Migration Information Source - The People Perceived as a Threat to Security: Arab Americans Since September 11

- ^ http://judiciary.senate.gov/testimony.cfm?id=960&wit_id=2719

- ^ Ranks of Latinos Turning to Islam Are Increasing; Many in City Were Catholics Seeking Old Muslim Roots

- ^ http://www.gallup.com/poll/116260/Muslim-Americans-Exemplify-Diversity-Potential.aspx Muslim Americans Exemplify Diversity, Potential

- ^ Among U.S. Religious Groups, Muslims Seen as Facing More Discrimination

- ^ Koszegi (1992), pg. 3

- ^ Rayford W. Logan. "Estevanico, Negro Discoverer of the Southwest: A Critical Reexamination." Phylon (1940-1956), Vol. 1, No. 4. (4th Qtr., 1940), pp. 305-314.

- ^ N. Brent Kennedy has speculated that during the period 1567-1587, Moors and Turks were brought to the present-day Carolinas, and that some of these intermarried with Native Americans, giving rise to the Melungeon communities of Southern Appalachia. Kennedy, N. Brent (1997). The Melungeons: The Resurrection of a Proud People: An Untold Story of Ethnic Cleansing in America. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press. pp. 118–122, 159. ISBN 0865545162.

In fact, it is likely that the Melungeons are a blend of the Powhatans, the Lumbees, and the Santa Elena colonists, with a strong Moorish/Turkish element

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Charles D. Russell, "Islam as a Danger to Republican Virtue: Broadening Religious Liberty in Revolutionary Pennsylvania," Pennsylvania History, Summer 2009, Vol. 76 Issue 3, pp 250-275

- ^ Robert Battistini, "Glimpses of the Other before Orientalism: The Muslim World in Early American Periodicals, 1785-1800," Early American Studies Spring 2010, Vol. 8#2 pp 446-474

- ^ "Savages of the Seas: Barbary Captivity Tales and Images of Muslims in the Early Republic," Journal of American Culture Summer 1990, Vol. 13#2 pp 75-84

- ^ Frank Lambert, The Barbary Wars: American Independence in the Atlantic World (2007)

- ^ http://www.loc.gov/loc/lcib/0205/tolerance.html

- ^ US State Dept. notes on Morocco

- ^ Treaty of Peace and Friendship Article 11. The Avalon Project. Yale Law School.

- ^ http://www.earlyamerica.com/lives/franklin/chapt10/

- ^ http://etext.virginia.edu/jefferson/quotations/jeff1650.htm

- ^ http://www.state.gov/secretary/rm/2009a/09/129232.htm

- ^ a b c M'Bow, Amadou Mahtar (2001). Islam and Muslims in the American continent. Beirut: Center of historical, economical and social studies. p. 109.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Edward E. Curtis, Muslims in America: A Short History (2009) ch 1

- ^ Sylviane A. Diouf, Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas (1998)

- ^

Samuel S. Hill, Charles H. Lippy, Charles Reagan Wilson (2005). Encyclopedia of religion in the South. Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press. p. 394.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Koszegi, Michael; Melton, J. Gordon (1992). Islam in North America: A Sourcebook. New York: Garland Publishing Inc. pp. 26–27.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gomez, Michael A. (1994). "Muslims in Early America". The Journal of Southern History. 60 (4). Southern Historical Association: 682. doi:10.2307/2211064.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Gomez, Michael A. (1994). "Muslims in Early America". The Journal of Southern History. 60 (4). Southern Historical Association: 692, 693, 695. doi:10.2307/2211064.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Thomas C. Parramore, "Muslim Slave Aristocrats in North Carolina," North Carolina Historical Review, April 2000, Vol. 77 Issue 2, pp 127-150

- ^ In 1991, a masjid in Fayetteville, North Carolina renamed itself Masjid Omar Ibn Said in his honor. Omar ibn Said Davidson Encyclopedia Tammy Ivins, June 2007

- ^ http://www.muslimsinamerica.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=15&Itemid=28

- ^ Muslim roots of the blues, Jonathan Curiel, San Francisco Chronicle August 15, 2004

- ^ "Religion: Ramadan". Time. 1937-11-15. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ Queen, Edward L., Stephen Prothero and Gardiner H. Shattuck Jr. 1996. The Encyclopedia of American Religious History. New York: Facts on File.

- ^ Ghazali, Abdul Sattar. "The number of mosque attendants increasing rapidly in America". American Muslim perspective.

- ^ a b Jacob Neusner (2003). pp.180-181. ISBN 978-0-664-22475-2.

- ^ Moorish Science Temple of America Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved on 2009-11-13.

- ^ The Muslim Program

- ^ John Esposito (2008-09-10) W.D. Mohammed: A Witness for True Islam The Washington Post. Retrieved on 2009-06-21.

- ^ Imam W. Deen Mohammed 1933 ~ 2008 - Chicago Tribune CAIR Chicago. Retrieved on 2009-11-12.

- ^ Richard Brent Turner (2003). Islam in the African-American experience. pp. 225-227. ISBN 978-0-253-21630-4.

- ^ Nation of Islam leader dies at 74 MSNBC. Retrieved on 2009-06-21.

- ^ Warith Deen Mohammed: Imam who preached a moderate form of Islam to black Americans The Independent. 15 September 2008. Retrieved on 2009-04-22.

- ^ Omar Sacirbey (2006-05-16) Muslims Look to Blacks for Civil Rights Guidance Pew Forum. Retrieved on 2009-07-29.

- ^ Farrakhan backs racial harmony BBC News (BBC). 2000-10-16. Retrieved on 2009-06-22.

- ^ Dodoo, Jan (May 29, 2001). "Nation of Islam". University of Virginia.

- ^ "Active U.S. Hate Groups in 2006". Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

- ^ American Religious Identification Survey 2008 Retrieved on 2009-11-12.

- ^ Miller, Tracy, ed. (2009). Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Muslim Population (PDF). Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ The 2005 Annual Megacensus of Religions. (2007). In Britannica Book of the Year, 2006. Retrieved January 6, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9432655

- ^ Understanding Islam by Susan Headden of U.S. News & World Report. April 7, 2008.

- ^ Ihsan Bagby, Paul M. Perl, Bryan T. Froehle (2010-02-20) [2]. Council on American-Islamic Relations (Washington, D.C.). Retrieved on 2010-02-20.

- ^ Tom W. Smith, Estimating the Muslim Population in the United States, New York, The American Jewish Committee, October 2001.

- ^ CAIR website, American Muslims: Population Statistics

- ^ Number of Muslims in the United States at Adherents.com. Retrieved on 6 January 2006

- ^ Private studies fuel debate over size of U.S. Muslim population - Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 28 October 2001

- ^ Portrait of Muslims - Beliefs & Practices Pew Research Center

- ^ Detroit Islamic Center Open Largest Mosque in United States Brittany Sterrett. June 2, 2005 Accessed August 19, 2007.

- ^ PROFILE OF THE US MUSLIM POPULATION Dr Barry A Kosmin & Dr Egon Mayer 2 October 2001

- ^ "Darul Uloom Chicago" (PDF). Shari'ah Board of America. p. 2. Retrieved 2007-08-19.

- ^ Jacoby, Jeff (January 10, 2007). "The Boston mosque's Saudi connection". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "SCHUMER: SAUDIS PLAYING ROLE IN SPREADING MAIN TERROR INFLUENCE IN UNITED STATES". United States Senator Charles Schumer. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ^ Alexiev, Alex. "Terrorism: Growing Wahhabi Influence in the United States". Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ^ a b c d e Muslim Americans: Middle Class and Mostly Mainstream Pew Research Center. 2007-05-22. Retrieved on 2009-07-21.

- ^ "Being Muslim in America" America.gov (United States Department of State). Retrieved on 2009-11-12.

- ^ Andrea Elliot (2007-03-11) Between Black and Immigrant Muslims, an Uneasy Alliance The New York Times. Retrieved on 2009-07-23.

- ^ http://www.allied-media.com/AM/index.html

- ^ United State Senate, Committee on the Judiciary , Testimony of Dr. J. Michael Waller October 12, 2003 [3]

- ^ Federal Bureau of Investigation - Congressional Testimony

- ^ United State Senate, Committee on the Judiciary, Testimony of Mr. Paul Rogers, President of the American Correctional Chaplains Association, October 12, 2003 [4]

- ^ Special Report: A Review of the Federal Bureau of Prisons' Selection of Muslim Religious Services Providers - Full Report

- ^ Patricia Smith. "Islam in America", New York Times Upfront. New York: Jan 9, 2006. Vol. 138, Iss. 8; pg. 10

- ^ Zogby phone survey

- ^ Stars, Stripes, Crescent - A reassuring portrait of America's Muslims. The Wall Street Journal, 24 August 2005

- ^ a b The Diversity of Muslims in the United States - Views as Americans - United States Institute of Peace. February 2006

- ^ For Muslims at AZ Airport, a Place to Wash Before Prayers, Arizona Republic, May 20, 2004

- ^ Indy Star Retrieved on 2008.

- ^ Few find quiet chapel at DIA, Shannon Hurd, Boulder Daily Camera, April 20, 2002

- ^ http://www.altmuslim.com/a/a/a/crescents_among_the_crosses_at_arlington_cemetery/

- ^ a b The Mosque In America CAIR. Retrieved on 2010-08-04.

- ^ Islamic Society of North America Official Website.

- ^ Islamic Circle of North America Official Website

- ^ Islamic Supreme Council of America Official Website.

- ^ Islamic Assembly of North America Official Website.

- ^ Muslim Student Association Official Website

- ^ Islamic Information Center Official Website.

- ^ Muslim Public Affairs Council Official Website

- ^ The American Islamic Congress Statement Of Principles

- ^ Free Muslims Coalition

- ^ Inner-City Muslim Action Network Official Website

- ^ Islamic Relief Official Website

- ^ a b c Views of Muslim-Americans hold steady after London Bombings - Pew Research Center. 26 July 2005

- ^ The latest NEWSWEEK Poll paints a complicated portrait of attitudes toward America's Muslims.

- ^ Restrictions on Civil Liberties, Views of Islam, & Muslim Americans - Cornell University. December 2005

- ^ Poll news CBS.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Template:PDFlink, Pew Research Center, 22 May 2007

- ^ "Major poll finds US Muslims Mostly Mainstream". VOA News. Voice of America. 1 June 2007. Retrieved 25 December 2008.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Tolerance.org: VIOLENCE AGAINST ARAB AND MUSLIM AMERICANS:Alabama to Massachusetts

- ^ a b Tolerance.org: VIOLENCE AGAINST ARAB AND MUSLIM AMERICANS:Michigan to Wisconsin

- ^ "Minnesota's Muslim cab drivers face crackdown". Reuters. April 17, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Target shifts Muslims who won't ring up pork products". MSNBC. March 17, 2007. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ http://www.startribune.com/kersten/story/1115081.html

- ^ Muslim prayers in school debated | The San Diego Union-Tribune

- ^ Bush like Hitler, says first Muslim in Congress The Telegraph

- ^ Congressman Admits 9/11 Error, Associated Press, July 18, 2007

- ^ Sun Times Retrieved on 2008.

- ^ a b c d Fact Sheet: Department of Justice Anti-Terrorism Efforts Since Sept. 11, 2001, U.S. Department of Justice, September 5, 2006

- ^ The Enemy Within (and the Need for Profiling) by Daniel Pipes. New York Post, via danielpipes.org, 24 January 2003

- ^ ‘American Jihad’ by Steven Emerson. Iranscope, 26 February 2002

- ^ Robert Spencer

- ^ Wahhabism and Islam in the U.S. - GlobalSecurity.org. 26 June 2003

- ^ Expert: Saudis have radicalized 80% of US mosques - Jerusalem Post. 8 December 2005

- ^ Schumer: Saudis Playing Role in Spreading Main Terror Influence in United States - Charles Schumer Press Release. September 10, 2003

- ^ ISNA Leadership Development Center News and Events

- ^ Peter Bergen on Jon Stewarts Daily Show - Comedy Central

- ^ Will the Extreme Right Succeed? Turning the War on Terror into a War on Islam - Media Monitors USA, Louay M. Safi. 29 December 2005

- ^ United Nations Report E/CN.4/1999/58/Add.1

External links

Organizations, people and events

- FriendlyCombatant.com

- Islam on Capitol Hill (Internet home of Islam affirmation event at Capitol Hill on September 25, 2009)

- Islamic Center of Beverly Hills

Guides and reference listings

- ?: information of Muslim communities and events in the greater Los Angeles area

- GaramChai.com: Mosques (listings of mosques in the United States)

Academia and news

- ?: Early Muslim Settlers 1500-1850[dead link]

- Allied Media Corporation: Muslim American Market: Muslim American Demographic Facts

- Allied Media Corporation: Muslim American Market: MUSLIM AMERICAN MEDIA

- The As-Sunnah Foundation of America: The Islamic Community In The United States: Historical Development

- DinarStandard: The Untapped American Muslim Consumer Market

- Euro Islam.info: Islam in the United States

- Internet Archive: An Oral History of Islam in Pittsburgh (2006)

- IslamAmerica: A Brief History of Islam in the United States[dead link]

- IslamOnline.net: Politicking US Muslims: How Can US Muslims Change Realities - Interview with Dr. Salah Soltan

- IslamOnline.net: US Muslims - Special Coverage[dead link]

- IslamOnline.net: What Goes First for American Muslims: A Guide to A Better-engaged Community

- Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance: How many Muslims are there in the U.S. and the rest of the world?

- The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life: Muslims Widely Seen As Facing Discrimination

- Pew Research Center: Publications: Muslim Americans: Middle Class and Mostly Mainstream

- The Pluralism Project at Harvard University: Distribution of Muslim Centers in the U.S.

- Qantara.de: African-American Muslims: The American Values of Islam

- San Francisco State University: Media Guide to Islam: Timeline of Islam in the United States

- Social Science Research Network: What Every Political Leader in America and the West should Know about the Arab-Islamic World

- SPIEGEL ONLINE INTERNATIONAL: A Lesson for Europe: American Muslims Strive to Become Model Citizens

- United States Institute of Peace: The Diversity of Muslims in the United States: Views as Americans

- TIME: Muslim in America (photo essay)

- Valparaiso University: Muslims as a Percentage of all Residents, 2000