History of education in the United States: Difference between revisions

→The High School Movement: added details |

→The High School Movement: add statistics and citation |

||

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

By 1900 educators argued that the [[post-literacy]] schooling of the masses at the secondary and higher levels, would improve citizenship, develop higher-order traits, and produce the managerial and professional leadership needed for rapid economic modernization. The commitment to expanded education past age 14 set the U.S. apart from Europe for much of the twentieth century.<ref name="Jurgen Herbst 1996"/> |

By 1900 educators argued that the [[post-literacy]] schooling of the masses at the secondary and higher levels, would improve citizenship, develop higher-order traits, and produce the managerial and professional leadership needed for rapid economic modernization. The commitment to expanded education past age 14 set the U.S. apart from Europe for much of the twentieth century.<ref name="Jurgen Herbst 1996"/> |

||

From 1910 to 1940, high schools grew rapidly in number and size, reaching out to a broader clientele. This phenomenon was uniquely American; in no other nation did secondary education undergo a quibble and changes. fastest growth came in states with greater wealth, more homogeneity of wealth, and less manufacturing activity than others. the high schools provided necessary skill sets for youth planning to teach school, and essential skills for those planning careers in white collar work and some high-paying blue collar jobs. Economist [[Claudia Goldin]] argues this rapid growth was facilitated by public funding, openness, gender neutrality, local (and also state) control, [[separation of church and state]], and an academic curriculum. The wealthiest European nations such as Germany and Britain had far more exclusivity to their education system and few youth attended past age 14. Apart from technical training schools, European secondary schooling was dominated by children of the wealthy and the social elites.<ref>Claudia Goldin, "The Human-Capital Century and American Leadership: Virtues of the Past", ''Journal of Economic History,'' (2001) vol. 61#2 pp 263-90</ref> |

From 1910 to 1940, high schools grew rapidly in number and size, reaching out to a broader clientele. In 1910, for example, only 9% percent of Americans had a high school diploma; in 1935, the rate was 40%.<ref>Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz, "Human Capital and Social Capital: The Rise of Secondary Schooling in America, 1910–1940," ''Journal of Interdisciplinary History'' 29 (1999): 683–723.</ref> This phenomenon was uniquely American; in no other nation did secondary education undergo a quibble and changes. fastest growth came in states with greater wealth, more homogeneity of wealth, and less manufacturing activity than others. the high schools provided necessary skill sets for youth planning to teach school, and essential skills for those planning careers in white collar work and some high-paying blue collar jobs. Economist [[Claudia Goldin]] argues this rapid growth was facilitated by public funding, openness, gender neutrality, local (and also state) control, [[separation of church and state]], and an academic curriculum. The wealthiest European nations such as Germany and Britain had far more exclusivity to their education system and few youth attended past age 14. Apart from technical training schools, European secondary schooling was dominated by children of the wealthy and the social elites.<ref>Claudia Goldin, "The Human-Capital Century and American Leadership: Virtues of the Past", ''Journal of Economic History,'' (2001) vol. 61#2 pp 263-90</ref> |

||

The United States chose a type of post-elementary schooling consistent with its particular features — stressing flexible, general and widely applicable skills that were not tied to particular occupations and geographic places had great value in giving students options in their lives. Skills had to survive transport across firms, industries, occupations, and geography in the dynamic American economy. |

The United States chose a type of post-elementary schooling consistent with its particular features — stressing flexible, general and widely applicable skills that were not tied to particular occupations and geographic places had great value in giving students options in their lives. Skills had to survive transport across firms, industries, occupations, and geography in the dynamic American economy. |

||

Revision as of 05:54, 6 August 2010

This article may be in need of reorganization to comply with Wikipedia's layout guidelines. (July 2010) |

The history of education in the United States, or foundations of education, covers the trends in educational philosophy, policy, institutions, and formal and informal learning in America from the 17th century to today.

Education in Colonial Days

The first American schools in the thirteen original colonies opened in the seventeenth century. Boston Latin School was founded in 1635 and is both the first public school and oldest existing school in the United States.[1] The nation's first institution of higher learning, Harvard University opened in 1638. As the colonies began to develop, all the New England colonies began to institute mandatory education schemes. In 1642 the Massachusetts Bay Colony made "proper" education compulsory; other New England colonies followed.[2] Similar statutes were adopted in other colonies in the 1640s and 1650s. The schools were all male, with few facilities for girls.[3] In the 18th century, "common schools," usually ungraded appeared. Although they were publicly supplied, they were not free, and instead were supported by tuition or "rate bills."

Religion

Religious denominations established most early colleges in order to train ministers. In New England there was an emphasis on literacy so that people could read the Bible. Most of the colleges which opened between 1640 and 1750 form the contemporary Ivy League, including Harvard, Yale, Columbia, Princeton, Brown, the University of Pennsylvania, and several others.[4] After the American Revolution, the new national government passed the Land Ordinance of 1785, which set aside a portion of every township in the unincorporated territories of the United States for use in public schools. After the Revolution, an emphasis was put on education, especially in the northern states, which rapidly established public schools. The US population had one of the highest literacy rates at the time.[5] Private academies flourished in the towns across the country, but rural areas (where most people lived) had few schools before the 1880s.

Women and girls

Tax-supported schooling for girls began as early as 1767 in New England. It was optional and some towns proved reluctant. Northampton, Massachusetts, for example, was a late adopter because it had many rich families who dominated the political and social structures and they did not want to pay taxes to aid poor families. Northampton assessed taxes on all households, rather than only on those with children, and used the funds to support a grammar school to prepare boys for college. Not until after 1800 did Northampton educate girls with public money. In contrast, the town of Sutton, Massachusetts, was diverse in terms of social leadership and religion at an early point in its history. Sutton paid for its schools by means of taxes on households with children only, thereby creating an active constituency in favor of universal education for both boys and girls.[6]

Historians point out that reading and writing were different skills in the colonial era. School taught both, but in places without schools reading was mainly taught to boys and also a few privileged girls. Men handled worldly affairs and needed to read and write. Girls only needed to read (especially religious materials). This educational disparity between reading and writing explains why the colonial women often could read, but could not write and could not sign their names—they used an "X".[7]

The education of elite women in Philadelphia after 1740 followed the British model developed by the gentry classes during the early 18th century. Rather than solely emphasizing ornamental aspects of women's roles, this new model encouraged women to engage in a more substantive education, reaching into the arts and sciences to emphasize their reasoning skills. Education had the capacity to help colonial women secure their elite status by giving them traits that their 'inferiors' could not easily mimic. Fatherly (2004) examines British and American writings that influenced Philadelphia during the 1740s-1770s and the ways in which Philadelphia women implemented and demonstrated their education.[8]

South

Generally the planter class hired tutors for the education of their children or sent them to private schools. During the colonial years, some sent their sons to England for schooling.

In the remote colony of Georgia at least ten grammar schools were in operation by 1770, many taught by ministers. Most had some government funding. Many were free to both male and female students. A study of women's signatures indicates a high degree of literacy in areas with schools.[9] Georgia's early promise faded after 1800, and indeed the entire rural South had limited schooling until after 1900.

Southern states established public school systems under Reconstruction biracial governments. There were public schools for blacks, but nearly all were segregated and white legislators consistently underfunded black schools. High schools becam available to whites (and some blacks) in the cities after 1900, but few rural Southerners of either race went beyond the 8th grade until after 1945.

Republican motherhood

By the early 19th century a new mood was alive in urban areas. Especially influential were the writings of Lydia Maria Child, Catharine Maria Sedgwick, and Lydia Sigourney, who developed the role of republican motherhood as a principle that united state and family by equating a successful republic with virtuous families. Women, as intimate and concerned observers of young children, were best suited to this role. By the 1840s, New England writers such as Child, Sedgwick, and Sigourney became respected models and advocates for improving and expanding education for females. Greater educational access meant formerly male-only subjects, such as mathematics and philosophy, were to be integral to curricula at public and private schools for girls. By the late 19th century, these institutions were extending and reinforcing the tradition of women as educators and supervisors of American moral and ethical values.[10]

The ideal of Republican motherhood pervaded the entire nation, greatly enhancing the status of women and demonstrating girls' need for education. The polish and frivolity of female instruction which characterized colonial times was replaced after 1776 by the realization that women had a major role in nation building and must become good republican mothers of good republican youth. Fostered by community spirit and financial donations, private female academies emerged in towns across the South as well as the North. Rich planters were particularly insistent on their daughters' schooling, since education served as a substitute for dowry in marriage arrangements. The academies usually provided a rigorous and broad curriculum that stressed writing, penmanship, arithmetic, and languages, especially French. By 1840, the female academies succeeded in producing a cultivated, well-read female elite ready for their roles as wives and mothers in southern aristocratic society.[11]

Growth of Public schools

In 1821, Boston started the first public high school in the United States. By the close of the 19th century, public secondary schools began to outnumber private ones.[12][13]

The "blue backed speller" of Noah Webster was by far the most common textbook from the 1790s until 1836, when the McGuffey Readers appeared. Both series emphasized civic duty and morality[14].

Over the years, Americans have been influenced by a number of European reformers; among them Pestalozzi, Herbart, and Montessori.[12]

Attendance

The school system remained largely private and unorganized until the 1840s. The first federal census to include questions on education and literacy, conducted in 1840, indicated that of the 1.8 million girls between five and fifteen (and 1.88 million boys of the same age) about 55% attended primary schools and academies.[15] The data tables do not note the actual attendance rates, but only reflect the static numbers at the time of the U.S. census. Beginning in the late 1830s, more private academies were established for girls for education past primary school, especially in northern states. Some offered classical education similar to that offered to boys.

Data from the indentured servant contracts of German immigrant children in Pennsylvania from 1771-1817 showed that the number of children receiving education increased from 33.3% in 1771-1773 to 69% in 1787-1804. Additionally, the same data showed that the ratio of school education versus home education rose from .25 in 1771-1773 to 1.68 in 1787-1804.[16] While some African Americans managed to achieve literacy, southern states prohibited schooling to enslaved blacks.

Starting to improve the education of teachers, early 1800s

Teaching young students was not perceived as an end goal for educated people. Adults became teachers without any particular skill except sometimes in the topic they were teaching. The checking of credentials was left to the local school board, who were mainly interested in the efficient use of limited taxes. This started to change with the introduction of two-year normal schools starting in 1823. By the end of the century, most teachers of elementary schools were trained in this fashion.[13]

Mann reforms

Education reformers such as Horace Mann of Massachusetts began calling for public education systems for all. Upon becoming the secretary of education in Massachusetts in 1837, Mann helped to create a statewide system, based on the Prussian model[17], of "common schools," which referred to the belief that everyone was entitled to the same content in education. These early efforts focused primarily on elementary education. The common-school movement began to catch on in the North. Connecticut adopted a similar system in 1849, and Massachusetts passed a compulsory attendance law in 1852.

Preparation for college

In the 1865-1914 era, the number and character of schools changed to meet the demands of new and larger cities and of new immigrants strange to American ways, and to adjust to the new spirit of reform permeating the country. High schools increased in number, adjusted their curriculum to prepare students for the growing state and private universities; education at all levels began to offer more utilitarian studies in place of an emphasis on the classics. John Dewey and other Progressives advocated changes from their base in teachers' colleges.[18]

Before 1920 most secondary education, whether private or public, emphasized college entry for a select few headed for college. Proficiency in Greek and Latin was emphasized. Abraham Flexner, under commission from the philanthropic General Education Board (GEB) wrote A Modern School (1916) calling for a deemphasis on the classics. The classics teachers fought back in a losing effort.[19]

German was preferred as a second, spoken language prior to World War I. An anti-German attitude that resulted from the war, promoted French as a second language instead. French survived as the second language of choice until the 1960s, when Spanish became popular.[20]

Compulsory laws

By 1900, 31 states required children to attend school from the ages of 8- to 14-years-old. As a result, by 1910 72 percent of American children attended school. Half the nation's children attended one-room schools. In 1918, every state required students to complete elementary school.

Assimilation

As the nation was majority Protestant in the 19th century, most states passed a constitutional amendment, called Blaine Amendments, forbidding tax money be used to fund parochial schools. There was anti-Catholic sentiment related to heavy immigration from Catholic Ireland after the 1840s, and a feeling that Catholic children should be educated in public schools to become American. Irish established parochial schools not only to protect their religion, but their culture.[21]

Catholics and German Lutherans, as well as Dutch Protestants, organized and funded their own elementary schools. Catholic communities also raised money to build colleges and seminaries to train teachers and religious to head their churches.[21][22] Most Catholics were German or Irish immigrants or their children, until the 1890s when large numbers began arriving from Italy and Poland. By 1890 the Irish, who controlled the Church in the U.S., had built an extensive network of parishes and parish schools ("parochial schools") across the urban Northeast and Midwest. The parochial schools met some opposition, as in the Bennett Law in Wisconsin in 1890, but they thrived. In 1925 the US Supreme Court ruled in Pierce v. Society of Sisters that students could attend private schools to comply with compulsory education laws.

It was not until 1910 that smaller cities began building high schools. By 1940, 50% of young adults had earned a high school diploma.[13]

The High School Movement

By 1900 educators argued that the post-literacy schooling of the masses at the secondary and higher levels, would improve citizenship, develop higher-order traits, and produce the managerial and professional leadership needed for rapid economic modernization. The commitment to expanded education past age 14 set the U.S. apart from Europe for much of the twentieth century.[13]

From 1910 to 1940, high schools grew rapidly in number and size, reaching out to a broader clientele. In 1910, for example, only 9% percent of Americans had a high school diploma; in 1935, the rate was 40%.[23] This phenomenon was uniquely American; in no other nation did secondary education undergo a quibble and changes. fastest growth came in states with greater wealth, more homogeneity of wealth, and less manufacturing activity than others. the high schools provided necessary skill sets for youth planning to teach school, and essential skills for those planning careers in white collar work and some high-paying blue collar jobs. Economist Claudia Goldin argues this rapid growth was facilitated by public funding, openness, gender neutrality, local (and also state) control, separation of church and state, and an academic curriculum. The wealthiest European nations such as Germany and Britain had far more exclusivity to their education system and few youth attended past age 14. Apart from technical training schools, European secondary schooling was dominated by children of the wealthy and the social elites.[24]

The United States chose a type of post-elementary schooling consistent with its particular features — stressing flexible, general and widely applicable skills that were not tied to particular occupations and geographic places had great value in giving students options in their lives. Skills had to survive transport across firms, industries, occupations, and geography in the dynamic American economy.

Support for the high school movement occurred at the grass-roots level of local cities and school systems. The federal government involvement included vocational education funding after 1916. States and religious bodies funded teacher training colleges.

Public schools were funded and supervised by independent districts that depended on taxpayer support. In dramatic contrast to the centralized systems in Europe, where national agencies made the major decisions, the American districts designed their own rules and curricula.[25]

College preparation

In the 1865-1914 era, the number and character of schools changed to meet the demands of new and larger cities and of new immigrants strange to American ways, and to adjust to the new spirit of reform permeating the country. High schools increased in number, adjusted their curriculum to prepare students for the growing state and private universities; education at all levels began to offer more utilitarian studies in place of an emphasis on the classics. John Dewey and other Progressives advocated changes from their base in teachers' colleges.[18]

Before 1920 most secondary education, whether private or public, emphasized college entry for a select few headed for college. Proficiency in Greek and Latin was emphasized. Abraham Flexner, under commission from the philanthropic General Education Board (GEB) wrote A Modern School (1916) calling for a deemphasis on the classics. The classics teachers fought back in a losing effort.[19]

German was preferred as a second, spoken language prior to World War I. An anti-German attitude that resulted from the war, promoted French as a second language instead. French survived as the second language of choice until the 1960s, when Spanish became popular.[20]

Higher education

At the beginning of the 20th century, fewer than 1,000 colleges with 160,000 students existed in the United States. Explosive growth in the number of colleges occurred at the end of the 1800s and early twentieth century. Philanthropists endowed many of these institutions. Wealthy philanthropists for example, established Stanford University, Carnegie Mellon University, Vanderbilt University and Duke University; John D. Rockefeller funded the University of Chicago without imposing his name on it.[26]

Land Grant Universities

Each state used federal funding from the Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Acts of 1862 and 1890 to set up "land grant colleges" that specialized in agriculture and engineering.

The 1890 act created all-black land grant colleges, which were dedicated primarily to teacher training. They also made important contributions to rural development, including the establishment of a traveling school program by Tuskegee Institute in 1906. Rural conferences sponsored by Tuskegee also attempted to improve the life of rural blacks. In recent years, the 1890 schools have helped train many students from less-developed countries who return home with the ability to improve agricultural production.[27]

Among the first were Purdue University, Michigan State University, Kansas State University, Cornell University (in New York), Texas A&M University, Pennsylvania State University, The Ohio State University and the University of California. Few alumni became farmers, but they did play an increasingly important role in the larger food industry, especially after the Extension system was set up in 1916 that put trained agronomists in every agricultural county.

The engineering graduates played a major role in rapid technological development.[28] Indeed, the land-grant college system produced the agricultural scientists and industrial engineers who constituted the critical human resources of the managerial revolution in government and business, 1862–1917, laying the foundation of the world's preeminent educational infrastructure that supported the world's foremost technology-based economy.[29]

Representative was Pennsylvania State University. The Farmers' High School of Pennsylvania (later the Agricultural College of Pennsylvania and then Pennsylvania State University), chartered in 1855, was intended to uphold declining agrarian values and show farmers ways to prosper through more productive farming. Students were to build character and meet a part of their expenses by performing agricultural labor. By 1875 the compulsory labor requirement was dropped, but male students were to have an hour a day of military training in order to meet the requirements of the Morrill Land Grant College Act. In the early years the agricultural curriculum was not well developed, and politicians in Harrisburg often considered it a costly and useless experiment. The college was a center of middle-class values that served to help young people on their journey to white-collar occupations.[30]

GI Bill

Following World War II, the GI Bill made college education possible for many veterans by paying tuition and living expenses. It helped create a widespread belief in the necessity of college education. It opened up higher education to millions of ambitious young men who would otherwise have been forced to immediately enter the job market. Most campuses became overwhelmingly male thanks to the GI Bill; by the end of the century women had reached parity in numbers.[31]

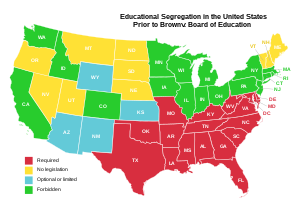

Segregation and integration

For much of its history, education in the United States was segregated (or even only available) based upon race. Early integrated schools such as the Noyes Academy, founded in 1835, in Canaan, New Hampshire, were generally met with fierce local opposition. For the most part, African Americans received very little to no formal education before the Civil War. Some free blacks in the North managed to become literate.

In the South where slavery was legal, many states had laws prohibiting teaching enslaved African Americans to read or write. A few taught themselves, others learned from white playmates or more generous masters, but most were not able to learn to read and write. Schools for free people of color were privately run and supported, as were most of the limited schools for white children. Poor white children did not attend school. The wealthier planters hired tutors for their children and sent them to private academies and colleges at the appropriate age.

During Reconstruction a coalition of freedmen and white Republicans in Southern state legislatures passed laws establishing public education. The Freedman's Bureau was created as an agency of the military governments that managed Reconstruction. It set up schools in many areas and tried to help to help educate and protect freedmen during the transition after the war. With the notable exception of the desegregated public schools in New Orleans, the schools were segregated by race. By 1900 more than 30,000 black teachers had been trained and put to work in the South, and the literacy rate had climbed to more than 50%, a major achievement in little more than a generation.[32]

Many colleges were set up for blacks; some were state schools like Booker T. Washington's Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, others were private ones subsidized by Northern missionary societies.

Although the African-American community quickly began litigation to challenge such provisions, in the 19th century Supreme Court challenges generally were not decided in their favor. The Supreme Court case of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) upheld the segregation of races in schools as long as each race enjoyed parity in quality of education (the "separate but equal" principle). However, few black students received equal education. They suffered for decades from inadequate funding, outmoded or dilapidated facilities, and deficient textbooks (often ones previously used in white schools).

Starting in 1914 and going into the 1930s, Julius Rosenwald, a philanthropist from Chicago, established the Rosenwald Fund to provide seed money for matching local contributions and stimulating the construction of new schools for African American children, mostly in the rural South. He worked in association with Booker T. Washington and architects at Tuskegee University to have model plans created for schools and teacher housing. With the requirement that money had to be raised by both blacks and whites, and schools approved by local school boards (controlled by whites), Rosenwald stimulated construction of more than 5,000 schools built across the South. In addition to Northern philanthrops and state taxes, African Americans went to extraordinary efforts to raise money for such schools.[33]

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s helped publicize the inequities of segregation. In 1954, the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education unanimously declared that separate facilities were inherently unequal and unconstitutional. By the 1970s segregated districts had practically vanished in the South.

Integration of schools has been a protracted process, however, with results affected by vast population migrations in many areas, and affected by suburban sprawl, the disappearance of industrial jobs, and movement of jobs out of former industrial cities of the North and Midwest and into new areas of the South. Although required by court order, integrating the first black students in the South met with intense opposition. In 1957 the integration of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, had to be enforced by federal troops. President Dwight D. Eisenhower took control of the National Guard, after the governor tried to use them to prevent integration. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, integration continued with varying degrees of difficulty. Some states and cities tried to overcome de facto segregation, a result of housing patterns, by using forced busing. This method of integrating student populations provoked resistance in many places, including northern cities, where parents wanted children educated in neighborhood schools.

Although full equality and parity in education has still to be achieved (many school districts are technically still under the integration mandates of local courts), technical equality in education had been achieved by 1970.[34]

Inequality

The comparative quality of education among rich and poor districts is still often the subject of dispute. While middle class African-American children have made good progress; poor minorities have struggled. With school systems based on property taxes, there are wide disparities in funding between wealthy suburbs or districts, and often poor, inner-city areas or small towns. "De facto segregation" has been difficult to overcome as residential neighborhoods have remained more segregated than workplaces or public facilities. Racial segregation has not been the only factor in inequities. Residents in New Hampshire challenged property tax funding because of steep contrasts between education funds in wealthy and poorer areas. They filed lawsuits to seek a system to provide more equal funding of school systems across the state.

Some scholars believe that transformation of the Pell Grant program to a loan program in the early 1980s has caused an increase in the gap between the growth rates of white, Asian-American and African-American college graduates since the 1970s.[35] Others believe the issue is increasingly related more to class and family capacity than ethnicity. Some school systems have used economics to create a different way to identify populations in need of supplemental help.

Special education

In 1975 Congress passed Public Law 94-142, Education of the Handicapped Act. One of the most comprehensive laws in the history of education in the United States, this Act brought together several pieces of state and federal legislation, making free, appropriate education available to all eligible students with a disability[36]. The law was amended in 1986 to extend its coverage to include younger children. In 1990 the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) extended its definitions and changed the label "handicap" to "disabilities". Further procedural changes were amended to IDEA in 1997[37].

Tenure for teachers

Professors were often able to receive tenure in public schools by the 1900s. This trend was applied to K-12 teachers starting around the 1950s. By the 21st century, tenure for K-12 teachers was being questioned and effectively replaced in several states around the country, including the District of Columbia.

Current policy

No Child Left Behind (as amended in 2004) was an amendment to the 1997 IDEA legislation. According to the National Center for Learning Disabilities, "For the nation's 2.9 million students with identified specific learning disabilities currently receiving special education services under IDEA, the challenging new provisions of NCLB create expanded opportunities for improved academic achievement and documentation of that improved performance." [38] The National Center for Learning Disabilities has issued a report on the effect of NCLB on special eduction.[39]

Historiography

Most histories of education deal with institutions or focus on the ideas histories of major reformers, but a new social history has recently emerged, focused on who were the students in terms of social background and social mobility[40]. Attention has often focused on minority[41] and ethnic students[42] The social history of teachers has also been studied in depth[43]

Historians have recently looked at the relationship between schooling and urban growth by studying educational institutions as agents in class formation, relating urban schooling to changes in the shape of cities, linking urbanization with social reform movements, and examining the material conditions affecting child life and the relationship between schools and other agencies that socialize the young.[44][45]

The most economics-minded historians have sought to relate education to changes in the quality of labor, productivity and economic growth, and rates of return on investment in education.[46] A major recent exemplar is Claudia Goldin and Lawrence F. Katz, The Race between Education and Technology (2009), on the social and economic history of 20th century American schooling.

Further reading

for a detailed bibliography see History of Education in the United States: Bibliography

- Altenbaugh; Richard J. Historical Dictionary of American Education (1999) online edition

- Button, H. Warren and Provenzo, Eugene F., Jr. History of Education and Culture in America. (1983). 379 pp.

- Cohen, Sol, ed. Education in the United States: A Documentary History (5 vol, 1974). 3400 pages of primary sources

- Cremin, Lawrence A. American Education: The Colonial Experience, 1607–1783. (1970); American Education: The National Experience, 1783–1876. (1980); American Education: The Metropolitan Experience, 1876-1980 (1990); 3 vol detailed scholarly history focused on the ideas of the educators

- Curti, M. E. The social ideas of American educators, with new chapter on the last twenty-five years. (1959).

- Goldin, Claudia. "The Human-Capital Century and American Leadership: Virtues of the Past", Journal of Economic History, (2001) vol. 61#2 pp 263-90 online

- Herbst, Juergen. The once and future school: Three hundred and fifty years of American secondary education. (1996). online edition

- Lucas, C. J. American higher education: A history. (1994). pp.; reprinted essays from History of Education Quarterly

- McClellan, B. Edward and Reese, William J., ed. The Social History of American Education. U. of Illinois Press, 1988. 370 pp.; reprinted essays from History of Education Quarterly

- Nasaw, David; Schooled to Order: A Social History of Public Schooling in the United States (1981) online version

- Parkerson, Donald H. and Parkerson, Jo Ann. Transitions in American Education: A Social History of Teaching. Routledge, 2001. 242 pp.

- Parkerson, Donald H. and Parkerson, Jo Ann. The Emergence of the Common School in the U.S. Countryside. Edwin Mellen, 1998. 192 pp.

- Rury, John L.; Education and Social Change: Themes in the History of American Schooling.'; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 2002. online version

- Spring, Joel. The American School: From the Puritans to No Child Left Behind. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill, 2008. 494 pp.

- Theobald, Paul. Call School: Rural Education in the Midwest to 1918. Southern Illinois U. Press, 1995. 246 pp.

- Tyack, David B. The One Best System: A History of American Urban Education (1974),

- Tyack, David B., and Elizabeth Hansot. Managers of virtue: Public school leadership in America, 1820–1980. (1982).

Journals

References

- ^ ""History of Boston Latin School—oldest public school in America"". BLS Web Site. Retrieved 2007-06-01.

- ^ Massachusetts Education Laws of 1642 and 1647. History of American Education], accessed February 15, 2006.

- ^ "Schooling, Education, and Literacy, In Colonial America". faculty.mdc.edu. 2010-04-01.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Agriculture and Education in Colonial America. North Carolina State University. URL accessed on February 28, 2006.

- ^ "High literacy rates in America...exceeded 90 per cent in some regions by 1800." Hannah Barker and Simon Burrows, eds. Press, Politics and the Public Sphere in Europe and North America 1760-1820 (2002) p. 141; for lower rates in Europe see p. 9.

- ^ Kathryn Kish Sklar, "The Schooling of Girls and Changing Community Values in Massachusetts Towns, 1750-1820," History of Education Quarterly 1993 33(4): 511-542

- ^ E. Jennifer Monaghan, "Literacy Instruction and Gender in Colonial New England," American Quarterly 1988 40(1): 18-41 in JSTOR

- ^ Sarah E. Fatherly, "Women's Education in Colonial Philadelphia," Pennsylvania Magazine Of History and Biography 2004 128(3): 229-256

- ^ Linda L. Arthur, "A New Look at Schooling and Literacy: The Colony of Georgia," Georgia Historical Quarterly 2000 84(4): 563-588

- ^ Sarah Robbins, "'The Future Good and Great of our Land': Republican Mothers, Female Authors, and Domesticated Literacy in Antebellum New England," New England Quarterly 2002 75(4): 562-591 in JSTOR

- ^ Catherine Clinton, "Equally Their Due: The Education of the Planter Daughter in the Early Republic," Journal of the Early Republic 1982 2(1): 39-60

- ^ a b [1]

- ^ a b c d Jurgen Herbst, The Once and Future School: Three Hundred and Fifty Years of American Secondary Education (1996)

- ^ John H. Westerhoff III, McGuffey and His Readers: Piety, Morality, and Education in Nineteenth-Century America (1978)

- ^ 1840 Census Data. Progress of the United States in Population and Wealth in Fifty years, accessed May 10, 2008.

- ^ Grubb, Farley. "Educational Choice in the Era Before Free Public Schooling: Evidence from German Immigrant Children in Pennsylvania, 1771-1817" The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 52, No. 2. (Jun., 1992), pp. 363-375.

- ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prussian_education_system#Emulation_of_the_Prussian_education_system_in_the_United_States

- ^ a b Lawrence A. Cremin, American Education: The Metropolitan Experience, 1876-1980 (1990)

- ^ a b William G. Wraga, "The Assault on 'The Assault on Humanism': Classicists Respond to Abraham Flexner's 'A Modern School'" Historical Studies in Education 2008 20(1): 1-31

- ^ a b John L. Watzke, Lasting Change in Foreign Language Education: A Historical Case for Change in National Policy (2003)

- ^ a b Walch (1996)

- ^ Dennis Clark, The Irish in Philadelphia: Ten Generations of Urban Experience, (1984), pp.96-101

- ^ Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz, "Human Capital and Social Capital: The Rise of Secondary Schooling in America, 1910–1940," Journal of Interdisciplinary History 29 (1999): 683–723.

- ^ Claudia Goldin, "The Human-Capital Century and American Leadership: Virtues of the Past", Journal of Economic History, (2001) vol. 61#2 pp 263-90

- ^ Claudia Goldin and Lawrence F. Katz, The Race between Education and Technology (2008)

- ^ Laurence Veysey, The Emergence of the American University (1965)

- ^ B. D. Mayberry, A Century of Agriculture in the 1890 Land Grant Institutions and Tuskegee University, 1890-1990 (1991)

- ^ Alan I. Marcus, ed., Engineering in a Land Grant Context: The Past, Present, and Future of an Idea. Marcus (2005)

- ^ Louis Ferleger and William Lazonick, "Higher Education for an Innovative Economy: Land-grant Colleges and the Managerial Revolution in America," Business & Economic History 1994 23(1): 116-128

- ^ Jim Weeks, "A New Race of Farmers: the Labor Rule, the Farmers' High School, and the Origins of the Pennsylvania State University," Pennsylvania History 1995 62(1): 5-30,

- ^ Glenn Altschuler and Stuart Blumin, The GI Bill: The New Deal for Veterans (2009)

- ^ James D. Anderson, The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935, (1988), pp. 244-245

- ^ Anderson Black Education in the South, 1880-1935 pp.158-161

- ^ Madison Desegregation Hearing To Be Held Tuesday, TheJacksonChannel, accessed February 14, 2006.

- ^ Adams, J.Q. (2001). Dealing with Diversity. Chicago, IL: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. ISBN 0-7872-8145-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jay G. Chambers and William T. Hartman, Special education policies: their history, implementation, and finance (1983)

- ^ Paul K. Longmore, "Making Disability an Essential Part of American History," OAH Magazine of History, July 2009, Vol. 23 Issue 3, pp 11-15

- ^ [2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ B. Edward McClellan, and William J. Reese, eds., The Social History of American Education (1988)

- ^ Robert A. Margo, Race and Schooling in the South, 1880–1950: An Economic History (1990)

- ^ David W. Galenson, "Ethnic difference in neighborhood effects on the school attendance of boys in early Chicago." History of Education Quarterly (1998) 38: 17–35.

- ^ Joel Perlmann and Robert A. Margo, Women's Work? American Schoolteachers, 1650–1920 (2001)

- ^ David A. Reeder, Schooling in the City: Educational History and the Urban Variable," Urban History, May 1992, Vol. 19 Issue 1, pp 23-38

- ^ Juergen Herbst, "The History of Education: State of the Art at the Turn of the Century in Europe and North America," Paedagogica Historica 35, no. 3 (1999)

- ^ Michael Sanderson, "Educational and Economic History: The Good Neighbours," History of Education, July /Sept 2007, Vol. 36 Issue 4/5, pp 429-445

External Links

- Articles needing cleanup from July 2010

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from July 2010

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from July 2010

- Wikipedia articles needing reorganization from July 2010

- Social history of the United States

- Cultural history of the United States

- History of education in the United States