Elizabeth Barrett Browning: Difference between revisions

Deleted incorrect and out of date material (a minor example, Flush was not a golden cocker spaniel) and material copied from Everett verbatim. |

Corrects information from outdated sources, deletes unattributed language from Victorian Web source |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

==Early life== |

==Early life== |

||

Elizabeth Barrett Moulton Barrett was born on 6 March 1806, in Coxhoe Hall, between the villages of [[Coxhoe]] and [[Kelloe]] in [[County Durham]], England. Her parents were Edward Barrett Moulton Barrett and Mary Graham Clarke; Elizabeth was the eldest of their 12 children (eight boys and four girls). All the children lived to adulthood except for one girl, who died at the age of four when Elizabeth was eight. The children in her family all had nicknames: Elizabeth's was "Ba". The Barrett family, some of whom were part Creole, had lived for centuries in Jamaica, where they owned sugar plantations and relied on [[slave]] labour. Elizabeth's father chose to raise his family in England while his fortune grew in Jamaica. The Graham |

Elizabeth Barrett Moulton Barrett was born on 6 March 1806, in Coxhoe Hall, between the villages of [[Coxhoe]] and [[Kelloe]] in [[County Durham]], England. Her parents were Edward Barrett Moulton Barrett and Mary Graham Clarke; Elizabeth was the eldest of their 12 children (eight boys and four girls). All the children lived to adulthood except for one girl, who died at the age of four when Elizabeth was eight. The children in her family all had nicknames: Elizabeth's was "Ba". The Barrett family, some of whom were part Creole, had lived for centuries in Jamaica, where they owned sugar plantations and relied on [[slave]] labour. Elizabeth's father chose to raise his family in England while his fortune grew in Jamaica. The Graham Clarke family wealth was as great as the Barrett family wealth. |

||

Elizabeth was baptized in 1809 at Kelloe Parish Church, though she had already been baptized by a family friend in the first week after she was born. |

Elizabeth was baptized in 1809 at Kelloe Parish Church, though she had already been baptized by a family friend in the first week after she was born. |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

The Barretts attended services at the nearest Dissenting chapel, and Edward was active in Bible and Missionary societies. Elizabeth was very close to her siblings while playing the maternal role. She had great respect for her father: she claimed that life was no fun without him, and her mother agreed, probably because they did not fully understand what the business really was that kept him when his trips got longer and longer. |

The Barretts attended services at the nearest Dissenting chapel, and Edward was active in Bible and Missionary societies. Elizabeth was very close to her siblings while playing the maternal role. She had great respect for her father: she claimed that life was no fun without him, and her mother agreed, probably because they did not fully understand what the business really was that kept him when his trips got longer and longer. |

||

==Publication== |

|||

Her first known poem was written at the age of six or eight. The manuscript is currently in the Berg Collection of the [[New York Public Library]]; the exact date is controversial because the "2" in the date 1812 is written over something else that is scratched out. When she was 14, her father paid for the publication of her long Homeric poem entitled ''The Battle of Marathon''. Barrett later referred to this as "[[Alexander Pope|Pope]]'s [[Homer]] done over again, or rather undone," but it is a considerable achievement. Her first collection of poems, ''An Essay on Mind, with Other Poems,'' was published in 1826.<ref name="ReferenceD">Donaldson, Sandra, ed., ''The Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning.''London: Pickering and Chatto,2010</ref> Its publication drew the attention of a blind scholar of the Greek language, Hugh Stuart Boyd, and that of another Greek scholar, [[Uvedale Price]], with whom she maintained a sustained scholarly correspondence. Among other neighbors was Mrs. James Martin from Colwall, with whom she kept up a correspondence throughout her life. |

|||

Elizabeth's first known poem was written at the age of six or eight, "On the Cruelty of Forcement to Man." The manuscript is currently in the Berg Collection of the [[New York Public Library]]; the exact date is controversial because the "2" in the date 1812 is written over something else that is scratched out. As a present for her fourteenth birthday her father underwrote the publication of her long Homeric poem entitled ''The Battle of Marathon'' (1820). Her first independent publication was "Stanzas Excited by Reflections on the Present State of Greece" in ''[[The New Monthly Magazine]]'' of May 1821; this was followed in the same publication two months later by "Thoughts Awakened by Contemplating a Piece of the Palm which Grows on the Summit of the Acropolis at Athens."<ref name="ReferenceA">Donaldson, Sandra, ed., ''The Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning.''London: Pickering and Chatto,2010</ref> |

|||

Her first collection of poems, ''An Essay on Mind, with Other Poems,'' was published in 1826.<ref name="ReferenceB">Donaldson, Sandra, ed., ''The Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning.''London: Pickering and Chatto,2010</ref> Its publication drew the attention of a blind scholar of the Greek language, Hugh Stuart Boyd, and that of another Greek scholar, [[Uvedale Price]], with whom she maintained a sustained scholarly correspondence. Among other neighbors was Mrs. James Martin from Colwall, with whom she also corresponded throughout her life. Later, at Boyd's suggestion, she translated [[Aeschylus]]' ''[[Prometheus Bound]]'' (published in 1833; retranslated in 1850). During their friendship Barrett studied Greek literature, including [[Homer]], [[Pindar]] and [[Aristophanes]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

In 1824, a lawsuit about the estate in Jamaica had been decided in favor of their cousin, precipitating their financial decline. |

|||

| ⚫ | At about age 20 Elizabeth began to battle with a lifelong illness, which the medical science of the time was unable to diagnose. She began to take morphine for the pain and eventually became addicted to the drug. This illness caused her to be frail and weak.<ref name="ReferenceA"/> [[Mary Russell Mitford]] described the young Elizabeth as having "a slight, delicate figure, with a shower of dark curls falling on each side of a most expressive face; large, tender eyes, richly fringed by dark eyelashes, and a smile like a sunbeam." [[Anne Thackeray Ritchie]] described her as being "very small and brown" with big, exotic eyes and an overgenerous mouth.[12] |

||

==Residences and publications== |

==Residences and publications== |

||

| Line 32: | Line 36: | ||

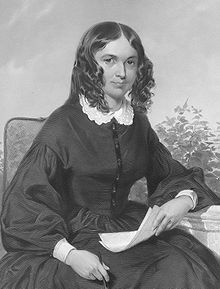

[[File:Elizabeth Barrett Browning.jpg|thumb|right|Elizabeth Browning]] |

[[File:Elizabeth Barrett Browning.jpg|thumb|right|Elizabeth Browning]] |

||

=== |

===Hope End, Sidmouth, and London=== |

||

On 30 June 1824, one of the leading newspapers in London, the Globe and Traveler, printed her ''Stanzas on the Death of Lord Byron''.<ref name="ReferenceB">Taplin, Gardner B. ''The Life of Elizabeth Browning'' New Haven: Yale University Press, 1957</ref> In the same year a lawsuit about her father's property estate in Jamaica had been decided in favor of their cousin, causing the start of their financial reversal. |

|||

At Boyd's suggestion, she translated [[Aeschylus]]' ''[[Prometheus Bound]]'' (published in 1833; retranslated in 1850). During their friendship Barrett absorbed a lot of Greek literature, including [[Homer]], [[Pindar]] and [[Aristophanes]]. From 1822 onwards, Elizabeth's interests tended more and more to the scholarly and literary. In 1825 she published The ''Rose and Zephyr'', her first published work. |

|||

| ⚫ | In 1828, Elizabeth’s mother died. She is buried at the Parish Church of St Michael and All Angels in Ledbury, next to her daughter Mary. |

||

| ⚫ | In 1828, Elizabeth’s mother died. She is buried at the Parish Church of St Michael and All Angels in Ledbury, next to her daughter Mary. In 1831 Elizabeth's beloved grandmother, Elizabeth Moulton, died. In addition to these personal losses, the family's finances were in trouble. Following the loss of the lawsuit concerning the Jamaican properties, the abolition of slavery in the early 1830s reduced Mr. Barrett's income. These financial losses in the early 1830s forced him to sell Hope End, and although the family were never poor, the place was seized and put up for sale to satisfy creditors. The investment that had given them revenue in Jamaica also ended with the abolition of slavery. |

||

| ⚫ | The family moved three times between 1832 and 1837, first to a white Georgian building in [[Sidmouth]], Devonshire, where they remained for three years. Later they moved on to Gloucester Place [[London]] |

||

| ⚫ | The family moved three times between 1832 and 1837, first to a white Georgian building in [[Sidmouth]], Devonshire, where they remained for three years. Later they moved on to Gloucester Place in [[London]]<ref>Taplin, Gardner, ''The Life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning'', New Haven: Yale University Press, 1957</ref>. |

||

===Wimpole Street=== |

|||

They finally settled at 50 [[Wimpole Street]], a place she had visited as a child. John Kenyon, a distant cousin, introduced her to celebrities of the literary world, including [[William Wordsworth]], [[Mary Russell Mitford]], [[Samuel Taylor Coleridge]], [[Alfred Lord Tennyson]] and [[Thomas Carlyle]]. |

They finally settled at 50 [[Wimpole Street]], a place she had visited as a child. John Kenyon, a distant cousin, introduced her to celebrities of the literary world, including [[William Wordsworth]], [[Mary Russell Mitford]], [[Samuel Taylor Coleridge]], [[Alfred Lord Tennyson]] and [[Thomas Carlyle]]. |

||

| Line 54: | Line 52: | ||

===Return to Wimpole Street=== |

===Return to Wimpole Street=== |

||

By the time of her return to Wimpole Street, |

By the time of her return to Wimpole Street, Elizabeth had become an invalid, spending most of her time in her upstairs room, seeing few people other than her immediate family. One of those she did see was her friend John Kenyon, a wealthy friend of the family and patron of the arts. She felt responsible for her brother's death because it was she who wanted him to be there with her. She got comfort from her spaniel named “Flush”, which had been a gift from Mary Mitford<ref name=Raymond, Meredith, and Mary Rose Sullivan, eds.> The Letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Mary Russell Mitford,'' Winfield, KS, 1983</ref>. |

||

She continued to write poetry, including ''The Cry of the Children'', published in 1842. This poem condemned [[child labour]] and helped bring about child labour reforms. At about the same time, she contributed some critical prose pieces to Richard Henry Horne's ''A New Spirit of the Age''. She also wrote ''The First Day’s Exile from Eden''. In 1844 she published two volumes of Poems, which included ''A Drama of Exile, A Vision of Poets'', and ''Lady Geraldine's Courtship''. “Since she was not burdened with any domestic duties expected of her sisters, Elizabeth could now devote herself entirely to the life of the mind, cultivating an enormous correspondence, reading widely”.<ref name="Pollock, Mary Sanders 2003">Pollock, Mary Sanders. Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning: A Creative Partnership. England: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2003.</ref> |

She continued to write poetry, including ''The Cry of the Children'', published in 1842. This poem condemned [[child labour]] and helped bring about child labour reforms. At about the same time, she contributed some critical prose pieces to Richard Henry Horne's ''A New Spirit of the Age''. She also wrote ''The First Day’s Exile from Eden''. In 1844 she published two volumes of Poems, which included ''A Drama of Exile, A Vision of Poets'', and ''Lady Geraldine's Courtship''. “Since she was not burdened with any domestic duties expected of her sisters, Elizabeth could now devote herself entirely to the life of the mind, cultivating an enormous correspondence, reading widely”.<ref name="Pollock, Mary Sanders 2003">Pollock, Mary Sanders. Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning: A Creative Partnership. England: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2003.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 06:04, 11 June 2010

Elizabeth Barrett Browning | |

|---|---|

An 1871 engraving of an 1859 photograph of Elizabeth Barrett Browning | |

| Occupation | Poet |

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (6 March 1806 – 29 June 1861) was one of the most prominent poets of the Victorian era. Her poetry was widely popular in both England and the United States during her lifetime.[1] A collection of her last poems was published by her husband, Robert Browning, shortly after her death.

Early life

Elizabeth Barrett Moulton Barrett was born on 6 March 1806, in Coxhoe Hall, between the villages of Coxhoe and Kelloe in County Durham, England. Her parents were Edward Barrett Moulton Barrett and Mary Graham Clarke; Elizabeth was the eldest of their 12 children (eight boys and four girls). All the children lived to adulthood except for one girl, who died at the age of four when Elizabeth was eight. The children in her family all had nicknames: Elizabeth's was "Ba". The Barrett family, some of whom were part Creole, had lived for centuries in Jamaica, where they owned sugar plantations and relied on slave labour. Elizabeth's father chose to raise his family in England while his fortune grew in Jamaica. The Graham Clarke family wealth was as great as the Barrett family wealth.

Elizabeth was baptized in 1809 at Kelloe Parish Church, though she had already been baptized by a family friend in the first week after she was born.

Later that year, after the fifth child, Henrietta, was born, Edward bought Hope End, a 500-acre (2.0 km2) estate near the Malvern Hills in Ledbury, Herefordshire. Elizabeth had "a large room to herself, with stained glass in the window, and she loved the garden where she tended white roses in a special arbour by the south wall"[2] Her time at Hope End would inspire her in later life to write Aurora Leigh.

Elizabeth was educated at home and attended lessons with her brother's tutor. This gave her a good education for a girl of that time, and she is said to have read passages from Paradise Lost and a number of Shakespearean plays, among other works, before the age of ten. During the Hope End period, she was "a shy, intensely studious, precocious child, yet cheerful, affectionate and lovable".[3] Her intellectual fascination with the classics and metaphysics was balanced by a religious obsession which she later described as "not the deep persuasion of the mild Christian but the wild visions of an enthusiast."[4][1]

The Barretts attended services at the nearest Dissenting chapel, and Edward was active in Bible and Missionary societies. Elizabeth was very close to her siblings while playing the maternal role. She had great respect for her father: she claimed that life was no fun without him, and her mother agreed, probably because they did not fully understand what the business really was that kept him when his trips got longer and longer.

Publication

Elizabeth's first known poem was written at the age of six or eight, "On the Cruelty of Forcement to Man." The manuscript is currently in the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library; the exact date is controversial because the "2" in the date 1812 is written over something else that is scratched out. As a present for her fourteenth birthday her father underwrote the publication of her long Homeric poem entitled The Battle of Marathon (1820). Her first independent publication was "Stanzas Excited by Reflections on the Present State of Greece" in The New Monthly Magazine of May 1821; this was followed in the same publication two months later by "Thoughts Awakened by Contemplating a Piece of the Palm which Grows on the Summit of the Acropolis at Athens."[2]

Her first collection of poems, An Essay on Mind, with Other Poems, was published in 1826.[5] Its publication drew the attention of a blind scholar of the Greek language, Hugh Stuart Boyd, and that of another Greek scholar, Uvedale Price, with whom she maintained a sustained scholarly correspondence. Among other neighbors was Mrs. James Martin from Colwall, with whom she also corresponded throughout her life. Later, at Boyd's suggestion, she translated Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound (published in 1833; retranslated in 1850). During their friendship Barrett studied Greek literature, including Homer, Pindar and Aristophanes.

In 1824, a lawsuit about the estate in Jamaica had been decided in favor of their cousin, precipitating their financial decline. At about age 20 Elizabeth began to battle with a lifelong illness, which the medical science of the time was unable to diagnose. She began to take morphine for the pain and eventually became addicted to the drug. This illness caused her to be frail and weak.[2] Mary Russell Mitford described the young Elizabeth as having "a slight, delicate figure, with a shower of dark curls falling on each side of a most expressive face; large, tender eyes, richly fringed by dark eyelashes, and a smile like a sunbeam." Anne Thackeray Ritchie described her as being "very small and brown" with big, exotic eyes and an overgenerous mouth.[12]

Residences and publications

Hope End, Sidmouth, and London

In 1828, Elizabeth’s mother died. She is buried at the Parish Church of St Michael and All Angels in Ledbury, next to her daughter Mary. In 1831 Elizabeth's beloved grandmother, Elizabeth Moulton, died. In addition to these personal losses, the family's finances were in trouble. Following the loss of the lawsuit concerning the Jamaican properties, the abolition of slavery in the early 1830s reduced Mr. Barrett's income. These financial losses in the early 1830s forced him to sell Hope End, and although the family were never poor, the place was seized and put up for sale to satisfy creditors. The investment that had given them revenue in Jamaica also ended with the abolition of slavery.

The family moved three times between 1832 and 1837, first to a white Georgian building in Sidmouth, Devonshire, where they remained for three years. Later they moved on to Gloucester Place in London[6].

They finally settled at 50 Wimpole Street, a place she had visited as a child. John Kenyon, a distant cousin, introduced her to celebrities of the literary world, including William Wordsworth, Mary Russell Mitford, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Alfred Lord Tennyson and Thomas Carlyle.

Elizabeth continued to write, contributing The Romaunt of Margaret, The Romaunt of the Page, The Poet's Vow, and other pieces to various periodicals. She corresponded with literary figures of the time, including Mary Russell Mitford. She and Mary became close friends, Mary helping her to further her literary ambition. In 1838 The Seraphim and Other Poems appeared as the first volume of Elizabeth's mature poetry to appear under her own name.

Torquay

In 1838, at her physician's insistence, Elizabeth moved from London to Torquay, on the Devonshire coast. Her brother Edward, one of her closest relatives, went along with her. Her father, Mr. Barrett, disapproved of Edward's going to Torquay but did not hinder his visit. The subsequent drowning of her brother Edward, in a sailing accident at Torquay in 1840, had a serious effect on her already fragile health; when they found his body after a couple of days, she had no strength for tears or words. They returned to Wimpole Street.

Return to Wimpole Street

By the time of her return to Wimpole Street, Elizabeth had become an invalid, spending most of her time in her upstairs room, seeing few people other than her immediate family. One of those she did see was her friend John Kenyon, a wealthy friend of the family and patron of the arts. She felt responsible for her brother's death because it was she who wanted him to be there with her. She got comfort from her spaniel named “Flush”, which had been a gift from Mary MitfordCite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page)..

She continued to write poetry, including The Cry of the Children, published in 1842. This poem condemned child labour and helped bring about child labour reforms. At about the same time, she contributed some critical prose pieces to Richard Henry Horne's A New Spirit of the Age. She also wrote The First Day’s Exile from Eden. In 1844 she published two volumes of Poems, which included A Drama of Exile, A Vision of Poets, and Lady Geraldine's Courtship. “Since she was not burdened with any domestic duties expected of her sisters, Elizabeth could now devote herself entirely to the life of the mind, cultivating an enormous correspondence, reading widely”.[7]

Meeting Robert Browning and works of this time

Her 1844 Poems made her one of the most popular writers in the land at the time and inspired Robert Browning to write to her, telling her how much he loved her poems. Kenyon arranged for Browning to meet Elizabeth in May 1845, and so began one of the most famous courtships in literature.

Elizabeth had produced a large amount of work and had been writing long before Robert Browning had ever published a word. However, he had a great influence on her writing, as did she on his; it is observable that Elizabeth’s poetry matured after meeting Robert. Two of Barrett’s most famous pieces were produced after she met Browning: Sonnets from the Portuguese and Aurora Leigh.

Some critics, however, point to him as an undermining influence: "Until her relationship with Robert Browning began in 1845, Barrett’s willingness to engage in public discourse about social issues and about aesthetic issues in poetry, which had been so strong in her youth, gradually diminished, as did her physical health. As an intellectual presence and a physical being, she was becoming a shadow of herself".[8]

Among Elizabeth's best known lyrics are Sonnets from the Portuguese (1850)— the "Portuguese" being her husband's pet name for her. The title also refers to the series of sonnets of the 16th-century Portuguese poet Luís de Camões; in all these poems she used rhyme schemes typical of the Portuguese sonnets.

The verse-novel Aurora Leigh, her most ambitious and perhaps the most popular of her longer poems, appeared in 1856. It is the story of a woman writer making her way in life, balancing work and love. The writings depicted in this novel are all based on similar, personal experiences that Elizabeth suffered through herself. The North American Review praised Elizabeth’s poem in these words: “ Mrs. Browning’s poems are, in all respects, the utterance of a woman—of a woman of great learning, rich experience, and powerful genius, uniting to her woman’s nature the strength which is sometimes thought peculiar to a man.”[9]

Robert Browning

The courtship and marriage between Robert Browning and Elizabeth were carried out secretly. Six years his elder and an invalid, she could not believe that the vigorous and worldly Browning really loved her as much as he professed to, and her doubts are expressed in the Sonnets from the Portuguese, which she wrote over the next two years. Love conquered all, however, and after a private marriage at St. Marylebone Parish Church, Browning imitated his hero Shelley by spiriting his beloved off to Italy in August 1846, which became her home almost continuously until her death. Elizabeth's loyal nurse, Wilson, who witnessed the marriage at the church, accompanied the couple to Italy.

Mr. Barrett disinherited Elizabeth, as he did each of his children who married: “The Mrs. Browning of popular imagination was a sweet, innocent young woman who suffered endless cruelties at the hands of a tyrannical papa but who nonetheless had the good fortune to fall in love with a dashing and handsome poet named Robert Browning. She finally escaped the dungeon of Wimpole Street, eloped to Italy, and lived happily ever after.”[10]

As Elizabeth had some money of her own, the couple were reasonably comfortable in Italy, and their relationship together was harmonious. The Brownings were well respected in Italy, and even famous, for they would be asked for autographs or stopped by people because of their celebrity. Elizabeth grew stronger and in 1849, at the age of 43, she gave birth to a son, Robert Wiedemann Barrett Browning, whom they called Pen. Their son later married but had no legitimate children, so there are apparently no direct descendants of the two famous poets.

“Several Browning critics have suggested that the poet decided that he was an “objective poet” and then sought out a “subjective poet” in the hope that dialogue with her would enable him to be more successful.”[7]

At her husband's insistence, the second edition of Elizabeth’s Poems included her love sonnets; as a result, her popularity shot up (as well as her critical regard), and her position as Victorian poetess du jour was cemented. In 1850, upon the occasion of the death of William Wordsworth, she was thought to be a serious contender for Poet Laureate, but the position went to Tennyson.

Decline

At the death of an old friend, G.B. Hunter, and then of her father, her health faded again, centering around deteriorating lung function. She was moved from Florence to Siena and to their summer home, The Villa Alberti.

In 1860 she issued a small volume of political poems titled Poems before Congress. These poems related to political issues for the Italians, “most of which were written to express her sympathy with the Italian cause after the outbreak of fighting in 1859”[5]. She dedicated this book to her husband.

Her last piece of work was A Musical Instrument, published in July 1862. She had also reprinted Last Poem, which became one of her best-known works.

In 1860 they returned to Rome, only to find that Elizabeth’s sister Henrietta had died, news which made Elizabeth weak and depressed. She became gradually weaker and died on 29 June 1861. She was buried in the English Cemetery of Florence. “On Monday July 1 the shops in the section of the city around Casa Guidi were closed, while Elizabeth was mourned with unusual demonstrations.”[11]

The nature of her illnesses is still unclear, although medical and literary scholars have speculated that longstanding pulmonary problems, combined with palliatives opiates, contributed to her decline.

Spiritual influence

Much of Elizabeth’s work has religious themes recurring throughout her literature. She had read and studied such famous literary works as Milton's Paradise Lost and Dante's Inferno. Elizabeth says in her writing, "We want the sense of the saturation of Christ's blood upon the souls of our poets, that it may cry through them in answer to the ceaseless wail of the Sphinx of our humanity, expounding agony into renovation. Something of this has been perceived in art when its glory was at the fullest. Something of a yearning after this may be seen among the Greek Christian poets, something which would have been much with a stronger faculty"[2]

She also believed that "Christ's religion is essentially poetry—poetry glorified.” She explores the religious aspect in many of her poems, especially in her early work, such as the Sonnets. She was interested in theological debate,[12] had learned Hebrew and read the Hebrew Bible. We find in the poem Aurora Leigh, for example, much religious imagery and allusion to images of the apocalypse.

Critical reception

American poet Edgar Allan Poe was inspired by Barrett Browning's poem Lady Geraldine's Courtship and specifically borrowed the poem's meter for his poem The Raven.[13] Poe had reviewed Barrett's work in the January 1845 issue of the Broadway Journal and said that "her poetic inspiration is the highest—we can conceive of nothing more august. Her sense of Art is pure in itself."[14] In return, she praised The Raven and Poe dedicated his 1845 collection The Raven and Other Poems to her, referring to her as "the noblest of her sex".[15]

Her poetry greatly influenced Emily Dickinson, who admired her as a woman of achievement. Her popularity in the United States and Britain was further advanced by her stands against social injustice, including slavery in the United States, anti-government subversive movements in Italy, and child labour.

In 1899 Lilian Whiting wrote a biography of Elizabeth entitled A study of Elizabeth Barrett Browning which describes her as "the most philosophical poet" and depicts her life as "a Gospel of applied Christianity". To Whiting, the term "art for art's sake" did not apply to Barrett Browning's work for the reason that each poem, distinctively purposeful, was borne of a more "honest vision". In this critical analysis, Whiting portrays Browning as a poet who uses knowledge of Classical literature with an "intuitive gift of spiritual divination".[16] In Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Angela Leighton suggests that the portrayal of Barrett Browning as the "pious iconography of womanhood" has distracted us from her poetic achievements. Leighton cites the 1931 play by Even Besier titled The Barretts of Wimpole Street as evidence that 20th century literary criticism of Barrett Browning's work has suffered more as a result of her popularity than poetic ineptitude.[17] The play was discovered and popularized by actress Katharine Cornell, for whom it became a signature role, and which she revived many times in her career. It was an enormous success, both artistically and commercially, and made Elizabeth's and Robert Browning's poetry popular. The play was revived several times and was adapted twice into movies.

Throughout the majority of the 20th Century, literary criticism of Barrett Browning's poetry remained sparse until her poems were discovered by the Feminist movement. She described herself as being inclined to reject several women's rights principles, suggesting in letters to Mary Russell Mitford and her husband that she believed that there was an inferiority of intellect in women.[17] However, feminist critics have used Deconstructionist theories of Jaques Derrida and others to explain the importance of Barrett Browning's voice to the feminist movement. Leighton writes that because she participates in the literary world, where voice and diction are dominated by popular accession to perceived masculine superiority, she "is defined only in mysterious opposition to everything that distinguishes the male subject who writes..."[17]

Works, First Publication

| Year | Title of Publications and editors | Publisher |

|---|---|---|

| 1820 | The Battle of Marathon: A Poem | Privately printed |

| 1826 | A Essay On Mind, with Other Poems | London: James Duncan |

| 1833 | Prometheus Bound, Translated from the Greek of Aeschlus,and Miscellaneous Poems | London: A.J. Valpy |

| 1838 | The Seraphim, and Other Poems | London: Saunders and Otley |

| 1844 | Poems (UK)/ A Drama of Exile, and other Poems (US) | London: Edward Moxon. New York: Henry G. Langley |

| 1850 | Poems("New Edition," 2 vols.)Revision of 1844 edition adding Sonnets from the Portuguese and others | London: Chapman & Hall ] |

| 1851 | Casa Guidi Window | London: Chapman & Hall |

| 1853 | Poems(3d ed.) | London: Chapman & Hall |

| 1854 | Two Poems:"A Plea for the Ragged Schools of London" by Barrett Browning and "The Twins" by Browning | London: Bradbury & Evans |

| 1856 | Poems(4th ed.) | London: Chapman & Hall (1857 printed on title page) |

| 1857 | Aurora Leigh | London: Chapman and Hall |

| 1860 | Poems Before Congress | London: Chapman & Hall |

| 1862 | Last Poems | London: Chapman & Hall |

| 1863 | The Greek Christian Poets and the English Poets | London: Chapman & Hall |

| 1877 | The Earlier Poems of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, 1826-1833, ed Richard Herne Shepheard | London: Bartholomew Robson |

| 1877 | Letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning Addressed to Richard Hengist Horne, with comments on contemporaries, 2 vols., ed. S.R. Townshend Mayer | London: Richard Bentley & Son |

| 1897 | Letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, 2 vols., ed. Frederic G. Kenyon | London:Smith, Elder,& Co. |

| 1899 | Letters of Robert Browing and Elizabeth Barrett Barrett 1845-1846, 2 vol., ed Robert W. Barrett Browning | London: Smith, Elder & Co. |

| 1914 | New Poems by Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, ed. Frederic G Kenyon | London:Smith, Elder & Co. |

| 1929 | Elizabeth Barrett Browning: Letters to Her Sister, 1846-1859, ed. Leonard Huxley | London: John Murray |

| 1935 | Twenty-Two Unpublished Letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning to Henrietta and Arabella Moulton Barrett | New York: United Feature Syndicate |

| 1939 | Letters from Elizabeth Barrett to B.R. Haydon, ed. Martha Hale Shackford | New York: Oxford University Press |

| 1954 | Elizabeth Barrett to Miss Mitford, ed. Betty Miller | London: John Murry |

| 1955 | Unpublished Letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Hugh Stuart Boyd, ed. Barbara P. McCarthy | New Heaven, conn.: Yale University Press |

| 1958 | Letters of the Brownings to George Barrett, ed. Paul Landis with Ronald E. Freeman | Urbana: University of Illinois Press |

| 1974 | Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Letters to Mrs. David Ogilvy, 1849-1861, ed. Peter N Heydon and Philip Kelley | New York: Quadrangle, The New York Times Book Co., and The Browning Institute |

| 1984 | The Brownings' Correspondence, ed. Phillip Kelley, Ronald Hudson, and Scott Lewis | Winfield, Kans.: Wedgestone Press |

Other Information

The University of Worcester has acknowledged Browning's local connection by naming a new building after her.

Browning is mentioned during the animated Peanuts television special Be My Valentine, Charlie Brown. In one scene, Sally receives a heart-shaped piece of candy with Sonnet Number 43 of Sonnets from the Portuguese ("How do I love thee? Let me count the ways...") written on it. Later, a heart-broken Linus Van Pelt yells "This one is for Elizabeth Barrett Browning!" in frustration, as he throws away the box of chocolates he bought for a teacher on whom he had an unrequited crush.

She was brought to popular accord in the play The Barretts of Wimpole Street, in a production by famed actress Katharine Cornell.

References

- ^ Burr, David Stanford. "Introduction".Sonnets from the Portuguese: a celebration of loveMacmillan (1986)

- ^ a b c Mander,Rosalie.Mrs Browning: The Story of Elizabeth Barrett.London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson,1980 Cite error: The named reference "ReferenceA" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Taplin, Gardner B. The Life of Elizabeth BrowningNew Haven: Yale University Press, 1957

- ^ Everett, Glenn,Life of Elizabeth Browning(2002)

- ^ a b Donaldson, Sandra, ed., The Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning.London: Pickering and Chatto,2010

- ^ Taplin, Gardner, The Life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1957

- ^ a b Pollock, Mary Sanders. Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning: A Creative Partnership. England: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2003.

- ^ Pollock, Mary Sanders. Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning: A Creative Partnership. England: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2003.

- ^ Kaplan, Cora. Aurora Leigh And Other Poems. London: The Women’s Press Lmited, 1978

- ^ Peterson, William S. Sonnets From The Portuguese. Massachusetts: Barre Publishing, 1977.

- ^ Taplin, Gardner B. The Life of Elizabeth Browning New Haven: Yale University Press, 1957

- ^ Lewis,Linda.Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Spiritual Progress. Missouri: Missouri University Press. 1997

- ^ Sova, Dawn B. Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York City: Checkmark Books, 2001: 208. ISBN 081604161X

- ^ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. New York City: Cooper Square Press, 1992: 160. ISBN 0815410387

- ^ Thomas, Dwight and David K. Jackson. The Poe Log: A Documentary Life of Edgar Allan Poe, 1809-1849. New York: G. K. Hall & Co., 1987: 591. ISBN 0783814011

- ^ Whiting, Lilian. A study of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Little, Brown and Company (1899)

- ^ a b c Leighton, Angela, Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Indiana University Press (1986) pp.8-18

Bibliography

- Barrett, R.A., The Barretts of Jamaica Wedgestone Press, 2000.

- Donaldson, Sandra, ed. The Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. 5 vols. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2010.

- Everett, Glenn,Life of Elizabeth Browning(2002)

- Markus, Julia. Dared and Done: Marriage of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning, Ohio University Press, 1995.

- Kaplan, Cora. Aurora Leigh And Other Poems. London: The Women’s Press Limited, 1978.

- Lewis,Linda.Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Spiritual Progress. Missouri: Missouri University Press. 1997

- Mander,Rosalie.Mrs Browning: The Story of Elizabeth Barrett.London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson,1980

- Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. New York City: Cooper Square Press, 1992: 160.

- Peterson, William S. Sonnets From The Portuguese. Massachusetts: Barre Publishing, 1977

- Pollock, Mary Sanders. Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning: A Creative Partnership. England: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2003

- Sova, Dawn B. Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York City: Checkmark Books, 2001: 208.

- Taplin, Gardner B. The Life of Elizabeth BrowningNew Haven: Yale University Press, 1957

- Thomas, Dwight and David K. Jackson. The Poe Log: A Documentary Life of Edgar Allan Poe, 1809-1849. New York: G. K. Hall & Co., 1987: 591.

External links

- Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning at Archive.org

- [3] The Life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning by Glenn Everett

- Poems by Elizabeth Barrett Browning at PoetryFoundation.org

- The Brownings: A Research Guide (Baylor University)

- The Barretts of Wimpole Street at IMDb

- Project Gutenberg e-text of Sonnets from the Portuguese

- Works by Elizabeth Barrett Browning at Project Gutenberg

- Poems by Elizabeth Barrett Browning An extensive collection of Browning's poetry.

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning Website, includes readings of Lady Geraldine's Courtship, Sonnets from the Portuguese, Runaway Slave at Pilgrim's Point, "Hiram Powers' Greek Slave", Casa Guidi Windows, and Aurora Leigh

- Reely's Poetry Pages Hear Sonnets 43 and 33

- "Archival material relating to Elizabeth Barrett Browning". UK National Archives.

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning at Find a Grave

- Browning Family Collection at the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin