Javan tiger: Difference between revisions

BhagyaMani (talk | contribs) replaced range map |

BhagyaMani (talk | contribs) started ==Distribution and ecology==; 2 refs |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

| status_system = IUCN3.1 |

| status_system = IUCN3.1 |

||

| PEX = 1980s |

| PEX = 1980s |

||

| status_ref = <ref>{{IUCN2008|assessors=Jackson, P., Nowell, K.|year= |

| status_ref = <ref>{{IUCN2008|assessors=Jackson, P., Nowell, K.|year=2008|title=Panthera tigris ssp. sondaica|id=41681|downloaded=19 March 2010}}</ref> |

||

| image = Panthera tigris sondaica 01.jpg |

| image = Panthera tigris sondaica 01.jpg |

||

| image_caption = Javan tiger photographed by Andries Hoogerwerf in [[Ujung Kulon National Park]], 1938<ref name="seidensticker1987">Seidensticker, J. (1987) Bearing Witness: Observations on the Extinction of ''Panthera tigris balica'' and ''Panthera tigris sondaica''. In: Tilson, R. L., Seal, U.S. (eds.) ''Tigers of the World''. Noyes Publications, New Jersey. [http://books.google.de/books?hl=de&lr=&id=YdC-wfyZwZEC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=Panthera+tigris+sondaica&ots=YHBRTiebpA&sig=fJcBcyel9yHkPFvYUkGbhKuKCfU#v=onepage&q=Panthera%20tigris%20sondaica&f=false book preview]</ref> |

| image_caption = Javan tiger photographed by Andries Hoogerwerf in [[Ujung Kulon National Park]], 1938<ref name="seidensticker1987">Seidensticker, J. (1987) Bearing Witness: Observations on the Extinction of ''Panthera tigris balica'' and ''Panthera tigris sondaica''. In: Tilson, R. L., Seal, U.S. (eds.) ''Tigers of the World''. Noyes Publications, New Jersey. [http://books.google.de/books?hl=de&lr=&id=YdC-wfyZwZEC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=Panthera+tigris+sondaica&ots=YHBRTiebpA&sig=fJcBcyel9yHkPFvYUkGbhKuKCfU#v=onepage&q=Panthera%20tigris%20sondaica&f=false book preview]</ref> |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

==Description== |

==Description== |

||

Javan tigers were very small compared to other subspecies of the [[Asia]]n mainland, but larger in size than [[Bali tiger]]s. Males weighed between {{convert|100|and|140|kg|lb|abbr=on}} on average with a body length of {{convert|200|to|245|cm|ft|abbr=on}}. Females were smaller than males and weighed |

Javan tigers were very small compared to other subspecies of the [[Asia]]n mainland, but larger in size than [[Bali tiger]]s. Males weighed between {{convert|100|and|140|kg|lb|abbr=on}} on average with a body length of {{convert|200|to|245|cm|ft|abbr=on}}. Females were smaller than males and weighed between {{convert|75|and|115|kg|lb|abbr=on}} on average.<br /> |

||

Their nose was long and narrow, occipital plane remarkably narrow and carnassials relatively long. They usually had long and thin stripes, which were slightly more numerous than of the [[Sumatran Tiger]].<ref>Mazák, J.H., Groves, C.P. (2006) ''A taxonomic revision of the tigers (Panthera tigris)''. Mammalian Biology 71 (5): 268–287 [http://arts.anu.edu.au/grovco/tiger%20SEAsia%20Mazak.pdf download pdf]</ref><br /> |

Their nose was long and narrow, occipital plane remarkably narrow and carnassials relatively long. They usually had long and thin stripes, which were slightly more numerous than of the [[Sumatran Tiger]].<ref>Mazák, J.H., Groves, C.P. (2006) ''A taxonomic revision of the tigers (Panthera tigris)''. Mammalian Biology 71 (5): 268–287 [http://arts.anu.edu.au/grovco/tiger%20SEAsia%20Mazak.pdf download pdf]</ref><br /> |

||

The smaller body size of the Javan Tiger is attributed to [[Bergmann’s rule]] and the size of the available prey species in Java, which are smaller than the [[Deer|cervid]] and [[bovid]] species distributed on the Asian mainland. However, the diameter of their tracks are larger than of [[Bengal Tiger]] in [[Bangladesh]], [[India]] and [[Nepal]].<ref name="seidensticker1986">Seidensticker, J. (1986) ''Large Carnivores and the Consequences of Habitat Insularization: Ecology and Conservation of Tigers in Indonesia and Bangladesh.'' Pp 1-42 In: Miller, S.D., Everett, D.D. (eds.) Cats of the world: biology, conservation and management. National Wildlife Federation, Washington DC.</ref> |

The smaller body size of the Javan Tiger is attributed to [[Bergmann’s rule]] and the size of the available prey species in Java, which are smaller than the [[Deer|cervid]] and [[bovid]] species distributed on the Asian mainland. However, the diameter of their tracks are larger than of [[Bengal Tiger]] in [[Bangladesh]], [[India]] and [[Nepal]].<ref name="seidensticker1986">Seidensticker, J. (1986) ''Large Carnivores and the Consequences of Habitat Insularization: Ecology and Conservation of Tigers in Indonesia and Bangladesh.'' Pp 1-42 In: Miller, S.D., Everett, D.D. (eds.) Cats of the world: biology, conservation and management. National Wildlife Federation, Washington DC.</ref> |

||

==Distribution and ecology== |

|||

At the end of the 18th century tigers inhabited most of Java. Around 1850 the people living in the rural areas still considered them a plague. Until 1940 tigers had retreated to remote mountainous and forested areas. Around 1970 the only known tigers lived in the region of Mount Betiri, the highest mountain ({{convert|1192|m|ft}}) in Java's southeast, which hadn’t been settled due to the rugged and slopy terrain. In 1972 the 500 km<sup>2</sup> area was gazetted as wildlife reserve. The last tigers were sighted there in 1976.<ref>Treep, L. (1973) ''On the Tiger in Indonesia (with special reference to its status and conservation).'' Report no. 164, Department of Nature Conservation and Nature Management, Wageningen, The Netherlands.</ref><ref name="seidensticker1987" /> |

|||

==Extirpation== |

==Extirpation== |

||

Revision as of 19:36, 25 March 2010

| Javan Tiger | |

|---|---|

| |

| Javan tiger photographed by Andries Hoogerwerf in Ujung Kulon National Park, 1938[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | P. t. sondaica

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Panthera tigris sondaica Temminck, 1844

| |

| |

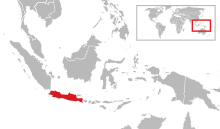

| Former range of the Javan tiger | |

The Javan tiger (Panthera tigris sondaica) is an extinct tiger subspecies. It inhabited the Indonesian island of Java until the 1980s and was one of the three subspecies limited to islands.

Description

Javan tigers were very small compared to other subspecies of the Asian mainland, but larger in size than Bali tigers. Males weighed between 100 and 140 kg (220 and 310 lb) on average with a body length of 200 to 245 cm (6.56 to 8.04 ft). Females were smaller than males and weighed between 75 and 115 kg (165 and 254 lb) on average.

Their nose was long and narrow, occipital plane remarkably narrow and carnassials relatively long. They usually had long and thin stripes, which were slightly more numerous than of the Sumatran Tiger.[3]

The smaller body size of the Javan Tiger is attributed to Bergmann’s rule and the size of the available prey species in Java, which are smaller than the cervid and bovid species distributed on the Asian mainland. However, the diameter of their tracks are larger than of Bengal Tiger in Bangladesh, India and Nepal.[4]

Distribution and ecology

At the end of the 18th century tigers inhabited most of Java. Around 1850 the people living in the rural areas still considered them a plague. Until 1940 tigers had retreated to remote mountainous and forested areas. Around 1970 the only known tigers lived in the region of Mount Betiri, the highest mountain (1,192 metres (3,911 ft)) in Java's southeast, which hadn’t been settled due to the rugged and slopy terrain. In 1972 the 500 km2 area was gazetted as wildlife reserve. The last tigers were sighted there in 1976.[5][1]

Extirpation

At the beginning of the 20th century 28 million people lived on the island of Java. The annual production of rice was insufficient to adequately supply the growing human population, so that within 15 years 150% more land was cleared for cultivating rice. In 1938 natural forest covered 23% of the island. 1975 only 8% forest stand remained; the human population had increased to 85 million people.[4] In this human-dominated landscape the extirpation of the Javan Tiger was a process intensified by the conjunction of several circumstances and events:

- Tigers and their prey were poisoned in many places during the period when their habitat was rapidly being reduced;

- Natural forests were increasingly fragmented after World War II for plantations of teak, coffee and rubber, which was unsuitable habitat for wildlife;

- Rusa deer, the tiger's most important prey species, was lost to disease in several reserves and forests during the 1960s;

- During the period of civil unrest after 1965 armed groups retreated to reserves, where they killed the remaining tigers.[1]

Last efforts

Until the mid-1960s tigers survived in three protected areas, which had been established during the 1920-1930s: Ujung Kulon, Leuwen Sancang und Baluran. But following the period of civil unrest no tigers were sighted there any more. In 1971 an older female was shot in a plantation near Mount Betiri in the southeast of Java. Since then not a single cub has been recorded in this last known refuge of the big cats. The area was upgraded to a wildlife reserve in 1972, at which time a small guard force was established and four habitat management projects initiated. The reserve was severely disrupted by two large plantations in the major river valleys, occupying the most suitable habitat for the tiger and its prey. In 1976, tracks were found in the eastern part of the reserve, suggesting the presence of 3-5 tigers. Only a few banteng survived close to the plantations, but tracks of rusa deer, the preferred prey of the Javan tiger, were not sighted.[6]

It now seems likely that this subspecies was made extinct in the 1980s, as a result of hunting and habitat destruction, but the extinction of this subspecies became increasingly probable from the 1950s onwards, when it is thought that fewer than 25 tigers remained in the wild. The last specimen was sighted in 1972. A track count in 1979 concluded that three of the tigers were in existence. It is possible that a small population of tigers continues to exist on West Java, where there were unverified sightings in the 1990s.[7][8]

Continued reported sightings

Occasional reports still surface of a few tigers to be found in east Java where the forested areas account for almost thirty percent of the land surface. Meru Betiri National Park, the least accessible area of the island, is located here and considered the most likely area for any remaining Javan tigers. This park is now coming under threat from three gold mining companies after the discovery of 80,000 tons[vague] of gold deposit within the locality.

Despite the continuing claims of sightings it is far more likely that, even with full protection and in reserve areas, the Javan tiger was unable to be saved. The 'tigers' are quite likely to be leopards seen from a distance.

At the present time the World Conservation Monitoring Centre lists this subspecies as having an 'outstanding query over status' rather than 'extinct', and some agencies are carrying out experiments using infrared activated remote cameras in an effort to photograph any tigers. Authorities are even prepared to initiate the move of several thousand people should tiger protection require this.[citation needed]

But until concrete evidence can be produced (expert sightings, pug marks, photographic evidence, attacks on people and animals), the Javan tiger must be considered yet another tiger subspecies which is probably extinct.[9]

In November 2008, an unidentified body of a female mountain hiker was found in Mount Merbabu National Park, Central Java, allegedly died from tiger attack. Villagers who discovered the body have also claimed some tiger sightings in the vicinity. [10]

Another recent sighting occurred in Magetan Regency, East Java, in January 2009. Some villagers claimed to see a tigress with two cubs wandering near a village adjacent to Lawu Mountain. This news immediately triggered mass panic. A subsequent investigation by local authorities found several fresh tracks in the location. However, by that time, those animals were already gone. [11]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Seidensticker, J. (1987) Bearing Witness: Observations on the Extinction of Panthera tigris balica and Panthera tigris sondaica. In: Tilson, R. L., Seal, U.S. (eds.) Tigers of the World. Noyes Publications, New Jersey. book preview

- ^ Template:IUCN2008

- ^ Mazák, J.H., Groves, C.P. (2006) A taxonomic revision of the tigers (Panthera tigris). Mammalian Biology 71 (5): 268–287 download pdf

- ^ a b Seidensticker, J. (1986) Large Carnivores and the Consequences of Habitat Insularization: Ecology and Conservation of Tigers in Indonesia and Bangladesh. Pp 1-42 In: Miller, S.D., Everett, D.D. (eds.) Cats of the world: biology, conservation and management. National Wildlife Federation, Washington DC.

- ^ Treep, L. (1973) On the Tiger in Indonesia (with special reference to its status and conservation). Report no. 164, Department of Nature Conservation and Nature Management, Wageningen, The Netherlands.

- ^ Seidensticker, J., Suyono, I. (1980) The Javan Tiger and the Meri-Betiri Reserve, a plan for management. International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, Gland. 167pp.

- ^ Bambang M. 2002. In search of 'extinct' Javan tiger. The Jakarta Post (October 30).

- ^ Harimau jawa belum punah! (Indonesian Javan Tiger website)

- ^ Save The Tiger Fund - The Javan Tiger

- ^ http://www.detiknews.com/read/2008/11/17/191947/1038555/10/pendaki-wanita-tewas-di-gunung-merbabu-diduga-diterkam-harimau

- ^ http://www.jawapos.co.id/radar/index.php?act=detail&rid=60292