Gharial: Difference between revisions

BhagyaMani (talk | contribs) →Appearance: moved photos up |

BhagyaMani (talk | contribs) →Distribution: made a list for better overview of countries + river systems; + refs; moved 1 photo to beg. of paragr. |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

==Distribution== |

==Distribution== |

||

[[File:Gharial in Karanali.JPG|thumb|Group of gharials in the Karnali River of [[Bardia National Park]], [[Nepal]]]] |

|||

They live on the Northern Indian subcontinent in [[Bhutan]] (almost extinct), [[Bangladesh]] (close to extinction), India (present in small numbers and increasing), Myanmar (possibly extinct), Nepal (present and increasing), and Pakistan (possibly extinct). They are usually found in the river systems of [[Indus River|Indus]] (Pakistan) and the [[Brahmaputra]] (Bangladesh, Bhutan and North eastern India), the [[Ganges]] (Bangladesh, India and Nepal), and the [[Mahanadi river|Mahanadi]] (in the [[rainforest]] biome) (India), with small numbers in Kaladan and the [[Irrawaddy River]] in [[Myanmar]]. It is [[sympatric]], in respective areas, with the [[Mugger crocodile]] |

|||

They inhabit the river systems of the Northern Indian subcontinent: |

|||

(''Crocodylus palustris'') and the [[Saltwater Crocodile]] (''Crocodylus porosus''). |

|||

* in India small populations are present and increasing in the [[Ganges]] and the [[rainforest]] biome of [[Mahanadi river|Mahanadi]] <ref>Bustard, H.R. (1983) ''Movement of wild Gharial, Gavialis gangeticus (Gmelin) in the River Mahanadi, Orissa (India).'' British Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 6: 287-291</ref>; |

|||

There have been some small-scale projects to breed and release Gharials, for example in Nepal's [[Chitwan National Park]].[http://www.wwfint.org/about_wwf/where_we_work/asia_pacific/where/nepal/our_solutions/conservation_nepal/tal/area/species/gharial/index.cfm WWF info about gharials] |

|||

* in Nepal small populations are present and slowly recovering in tributaries of the Ganges, such as the Narayani-Rapti river system in [[Chitwan National Park]] and the Karnali-Babai river system in [[Bardia National Park]] <ref>Maskey, T.M., Percival, H.F. (1994) ''Status and Conservation of Gharial in Nepal.'' Presented at the 12th Working Meeting of the Crocodile Specialist Group, Thailand.</ref><ref>Priol, P. (2003) ''Gharial field study report.'' A report submitted to Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, Kathmandu, Nepal.</ref>; |

|||

* in the [[Brahmaputra]] of [[Bangladesh]] and North eastern India; |

|||

* in [[Myanmar]] few specimen survive in Kaladan and the [[Irrawaddy River]]. |

|||

They are possibly extinct in [[Pakistan]]'s [[Indus River]], and close to extinction in [[Bhutan]] and [[Bangladesh]]. They are [[sympatric]], in respective areas, with the [[Mugger crocodile]] (''Crocodylus palustris'') and the [[Saltwater Crocodile]] (''Crocodylus porosus''). <ref>Rao, R.J., Choudhury, B.C. (1990) ''Sympatric distribution of Gharial Gavialis gangeticus and Mugger Crocodylus palustris in India.'' Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, Vol. 89: 313-314</ref> |

|||

There have been some small-scale projects to breed and rehabilitate gharials, i.e. in Nepal's [[Chitwan National Park]]. |

|||

A good spot to see the gharial is the [[National Chambal Sanctuary]] in [[Uttar Pradesh]], or at the [[Honolulu Zoo]] on [[Oahu]]. |

|||

==Habitat== |

==Habitat== |

||

Revision as of 15:18, 17 March 2010

| Gharial | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Gavialis

|

| Species: | G. gangeticus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Gavialis gangeticus (Gmelin, 1789)

| |

| |

The gharial (Hindi : घऱियाल, Marathi : सुसर Susar) (Gavialis gangeticus), sometimes called the Indian gavial or gavial, is one of two surviving members of the family Gavialidae, a long-established group of crocodile-like reptiles with long, narrow jaws. It is a critically endangered species. The gharial is one of the longest of all living crocodilians.[1]

Ancestry

The fossil history of the Gavialoidea is quite well known, with the earliest examples diverging from the other crocodilians in the late Cretaceous. The most distinctive feature of the group is the very long, narrow snout, which is an adaptation to a diet of small fish. Although gharials have sacrificed the great mechanical strength of the robust skull and jaw that most crocodiles and alligators have, and in consequence cannot prey on large creatures, the reduced weight and water resistance of their lighter skull and very narrow jaw gives gharials the ability to catch rapidly moving fish, using a side-to-side snapping motion.

The earliest gharial may have been related to the modern types: some died out at the same time as the dinosaurs (at the end of the Cretaceous), others survived until the early Eocene. The modern forms appeared at much the same time, evolving in the estuaries and coastal waters of Africa, but crossing the Atlantic to reach South America as well. At their peak, the Gavialoidea were numerous and diverse; they occupied much of Asia and America up until the Pliocene. One species, Rhamphosuchus crassidens of India, is believed to have grown to an enormous 15 metres (~50 feet) or more.

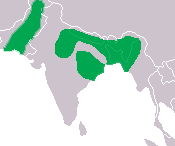

Distribution

They inhabit the river systems of the Northern Indian subcontinent:

- in India small populations are present and increasing in the Ganges and the rainforest biome of Mahanadi [2];

- in Nepal small populations are present and slowly recovering in tributaries of the Ganges, such as the Narayani-Rapti river system in Chitwan National Park and the Karnali-Babai river system in Bardia National Park [3][4];

- in the Brahmaputra of Bangladesh and North eastern India;

- in Myanmar few specimen survive in Kaladan and the Irrawaddy River.

They are possibly extinct in Pakistan's Indus River, and close to extinction in Bhutan and Bangladesh. They are sympatric, in respective areas, with the Mugger crocodile (Crocodylus palustris) and the Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus). [5]

There have been some small-scale projects to breed and rehabilitate gharials, i.e. in Nepal's Chitwan National Park.

Habitat

Riverine—most adapted to the calmer areas in the deep fast moving rivers. The physical attributes of the gharial do not make it very suited for moving about on land. In fact the only reasons the gharial leaves the water is either to bask in the sun or to nest on the sandbanks of the river.

Appearance

The species has a characteristic elongated, narrow snout, similar only to the closely related False gharial, (Tomistoma schlegelii). The snout shape varies with the age of the saurian. The snout becomes progressively thinner the older the gharial gets. The bulbous growth on the tip of the male's snout is called a 'ghara' (after the Indian word meaning 'pot'), present in mature individuals. The ghara is used to generate a resonant hum during vocalization. It acts as a visual lure for attracting females and it is also used to make bubbles which have been associated with the mating rituals of the species.

The elongated jaws are lined with many interlocking, razor-sharp teeth - an adaptation to the diet (predominantly fish in adults). This species is one of the largest of all crocodilian species, being the only crocodilian besides the Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) and nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) with multiple records of attaining a length of 6 m (20 feet) and a weight of 1000 kg (2200 lbs),[6] although a majority of gharials do not grow past 5 m (16.5 feet) and about 680 kg (1500 lb).[7] The three largest examples reported were a 6.5 m (21.5 ft) gharial killed in the Gogra River of Faizabad in August 1920; a 6.3 m (21 ft) individual shot in the Cheko River of Jalpaiguri in 1934; and a giant taped at 7 m (23 ft) which was shot in the Kosi River of northern Bihar in January 1924. [8] The average size of mature gharials is 3.6-4.5 m (12.2-15.5 ft)[9] about the same as for male Saltwater Crocodiles and Nile Crocodiles. The leg musculature of the gharial does not enable it to raise its body off the ground (on land) to achieve the high-walk gait—being able only to push its body forward across the ground ('belly-sliding'), although it can do this with some speed when required. However, when in water, the gharial is the most nimble and quick of all the crocodilians in the world. The tail seems overdeveloped and is laterally flattened, more so than other crocodilians, which enables it to achieve excellent aquatic locomotive abilities.

The gharial has 27 to 29 upper and 25 or 26 lower teeth on each side. These teeth are not received into interdental pits; the first, second, and third mandibular teeth fit into notches in the upper jaw. The front teeth are the largest. The gharial's snout is narrow and long, with a dilation at the end and its nasal bones are comparatively short and are widely separated from the pre-maxillaries. The nasal opening of a gharial is smaller than the supra-temporal fossae. The gharial's lower anterior margin of orbit (jugal) is raised and its mandibular symphysis is extremely long, extending to the 23rd or 24th tooth. A dorsal shield is formed from four longitudinal series of juxtaposed, keeled, and bony scutes. [10]

The length of the snout is 3.5 (in adults) to 5.5 times (in young) the breadth of the snout's base. Nuchal and dorsal scutes form a single continuous shield composed of 21 or 22 transverse series. Gharials have an outer row of soft, smooth, or feebly-keeled scutes in addition to the bony dorsal scutes. They also have two small post-occipital scutes.

The outer toes of a gharial are two-thirds webbed, while the middle toe is only one-third webbed. Gharials have a strong crest on the outer edge of the forearm, leg, and foot. Typically, adult gharials consist of a dark olive color tone while young ones are pale olive, with dark brown spots or cross-bands.[10]

Diet

Young gharials eat insects, larvae, and small frogs. Mature adults feed almost solely on fish, although some individuals have been known to scavenge dead animals. Their snout morphology is ideally suited for piscivory; their long, narrow snouts offer very little resistance to water in swiping motions to snap up fish in the water. Their numerous needle-like teeth are ideal for holding on to struggling, slippery fish. Gharials will often use their body to corral fish against the bank where they can be more easily snapped up.[11]

Danger to humans

The gharial is not a man-eater and is sensitive towards humans. Despite its immense size, its thin and fragile jaws make it physically incapable and impossible to consume a large animal, especially a human being. The myth that gharials eat humans may come partly from their similar appearance to Crocodiles and also since jewelry has been found in their stomachs. However, the gharial may have swallowed this jewelry while scavenging corpses or as gastroliths used to aid digestion or buoyancy management.

Breeding

The mating season is during November through December and well into January. The nesting and laying of eggs takes place in the dry season of March, April, and May. This is because during the dry season the rivers shrink a bit and the sandy river banks are available for nesting. Between 30 and 50 eggs are deposited into the hole that the female digs up before it is covered over carefully. After about 90 days, the juveniles emerge, although there is no record of the female assisting the juveniles into the water after they hatch (probably because their jaws are not suited for carrying the young due to the needle like teeth). However, the mother does protect the young in the water for a few days until they learn to fend for themselves.

Conservation

In the 1970s the gharial came to the brink of extinction and even now remains on the critically endangered list. The conservation efforts of the environmentalists in cooperation with several governments has led to some reduction in the threat of extinction. Some hope lies with the conservation and management programs in place as of 2004. Full protection was granted in the 1970s in the hope of reducing poaching losses, although these measures were slow to be implemented at first. Now there are 9 protected areas for this species in India which are linked to both captive breeding and 'ranching' operations where eggs collected from the wild are raised in captivity (to reduce mortality due to natural predators) and then released back into the wild (the first being released in 1981). More than 3000 animals have been released through these programs, and the wild population in India is estimated at around 1500 animals—with perhaps between one and two hundred animals in the remainder of its range. The release of captive gharials has not met with the success that was expected. Recently more than 100 gharials died in India in the Chambal River from an unknown cause with gout-like symptoms. This recent death toll is expected to have decreased the number of breeding pairs to less than 400. Tests of the carcasses conducted at the IVRI suggest the possibility of poisoning by metal pollutants.

Recently this species has moved from Endangered to Critically Endangered on the 2007 Red List of endangered species of animals and plants issued by the World Conservation Union, and qualifies for protection under the CITES (Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species) Appendix II.[12][13]

Taxonomy

The gharial and its extinct relatives are grouped together by taxonomists in several different ways:

- If the three surviving groups of crocodilians are regarded as separate families, then the gharial becomes one of two members of the Gavialidae, which is related to the families Crocodylidae (crocodiles) and Alligatoridae (alligators and caymans).

- Alternatively, the three groups are all classed together as the family Crocodylidae, but belong to the subfamilies Gavialinae, Crocodylinae, and Alligatorinae.

- Finally, palaentologists tend to speak of the broad lineage of gharial-like creatures over time using the term Gavialoidea.

Janke et al. (2005), using molecular genetic evidence, found the gharial and the false gharial (Tomistoma) to be close relatives, and placed them together in the same family.

Common names include: Indian gharial, Indian gavial, Fish-eating crocodile, Gavial del Ganges, Gavial du Gange, Long-nosed crocodile, Bahsoolia, Chimpta, Lamthora, Mecho Kumhir, Naka, Nakar, Shormon, Thantia, Thondre, Garial.

Classification

- Order Crocodilia

- Superfamily Gavialoidea

- Genus †Eothoracosaurus

- Genus †Thoracosaurus

- Genus †Eosuchus

- Genus †Argochampsa

- Family Gavialidae

- Subfamily Gavialinae

- Genus Gavialis

- Gavialis gangeticus - modern gharial

- †Gavialis curvirostris

- †Gavialis breviceps

- †Gavialis bengawanicus

- †Gavialis lewisi

- Genus Gavialis

- Subfamily Tomistominae

- Genus Tomistoma

- Tomistoma schlegelii, false gharial or Malayan gharial

- †Tomistoma lusitanica

- †Tomistoma cairense

- Genus †Eogavialis

- †Eogavialis africanus

- †Eogavialis andrewsi

- Genus †Kentisuchus

- Genus †Gavialosuchus

- Genus †Paratomistoma

- Genus †Thecachampsa

- Genus †Rhamphosuchus

- Genus †Toyotamaphimeia

- Genus Tomistoma

- Subfamily †Gryposuchinae

- Genus †Aktiogavialis

- Genus †Gryposuchus

- Genus †Ikanogavialis

- Genus †Siquisiquesuchus

- Genus †Piscogavialis

- Genus †Hesperogavialis

- Subfamily Gavialinae

- Superfamily Gavialoidea

Appearances in popular culture

- In the PlayStation 2 video game, Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater, one of the more noted animals that Naked Snake can consume for his survival is the Indian Gavial. It replenishes significant amounts of stamina, while causing Snake to express utmost satisfaction. A crocodile cap is also an obtainable item that can be used to scare away unsuspecting enemy soldiers. The Indian Gavials in the game are generally not too dangerous on land, inflicting only minor damage by striking the game's protagonist with their tails. However, if Naked Snake is attacked by one while in the water, it kills him instantly. Furthermore, nearby Gavials are provoked to attack Snake if he wears the croc cap in the water.

- The Ravnica: City of Guilds expansion of the Magic: The Gathering trading card game features a "Crocodile" creature called Grayscaled Gharial,[14] and the Shards of Alara expansion includes the creature Algae Gharial.[15]

- In Esperanto, the verb gaviali ("to gharial") means to speak Esperanto in a situation where another language would be more appropriate.

References

- ^ "Crocodilian species - Gharial". Flmnh.ufl.edu. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- ^ Bustard, H.R. (1983) Movement of wild Gharial, Gavialis gangeticus (Gmelin) in the River Mahanadi, Orissa (India). British Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 6: 287-291

- ^ Maskey, T.M., Percival, H.F. (1994) Status and Conservation of Gharial in Nepal. Presented at the 12th Working Meeting of the Crocodile Specialist Group, Thailand.

- ^ Priol, P. (2003) Gharial field study report. A report submitted to Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, Kathmandu, Nepal.

- ^ Rao, R.J., Choudhury, B.C. (1990) Sympatric distribution of Gharial Gavialis gangeticus and Mugger Crocodylus palustris in India. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, Vol. 89: 313-314

- ^ <http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/reptiles/gavial.html>

- ^ "San Diego Zoo's Animal Bytes: Alligator & Crocodile". Sandiegozoo.org. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- ^ Wood, The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Sterling Pub Co Inc (1983), ISBN 978-0851122359

- ^ Gavialis gangeticus. "Gavials (Gharials), Gavial (Gharial) Pictures, Gavial (Gharial) Facts - National Geographic". Animals.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- ^ a b Boulenger, G. A. 1890. Fauna of British India. Reptilia and Batrachia.

- ^ Piper, Ross (2007), Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals, Greenwood Press.

- ^ "Choudhury, B.C., Singh, L.A.K., Rao, R.J., Basu, D., Sharma, R.K., Hussain, S.A., Andrews, H.V., Whitaker, N., Whitaker, R., Lenin, J., Maskey, T., Cadi, A., Rashid, S.M.A., Choudhury, A.A., Dahal, B., Win Ko Ko, U., Thorbjarnarson, J & Ross, J.P. 2007. Gavialis gangeticus. In: IUCN 2007. 2007 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. <www.iucnredlist.org>>".

- ^ “At 200, gharials now on critically-endangered list” by Neelam Raaj , TNN, The Times of India, 13 Sep 2007

- ^ http://www.hraj.cz/ravnica/karty/grayscaled_gharial.jpg

- ^ "Algae Gharial (Shards of Alara) - Gatherer - Magic: The Gathering". Gatherer.wizards.com. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

Bibliography

- Template:IUCN2006 Listed as Endangered (EN C2a, E v2.3)

- Janke A, Gullberg A, Hughes S, Aggarwal RK, Arnason U. (2005). "Mitogenomic analyses place the gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) on the crocodile tree and provide pre-K/T divergence times for most crocodilians." J Mol Evol. 61(5):620-6.