History of the anti-nuclear movement: Difference between revisions

cat |

ref |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

{{Anti-nuclear movement}} |

{{Anti-nuclear movement}} |

||

The application of [[nuclear technology]], both as a source of energy and as an instrument of war, has been controversial.<ref name=contr>Robert Benford. [http://www.jstor.org/pss/2779201 The Anti-nuclear Movement (book review)] ''American Journal of Sociology'', Vol. 89, No. 6, (May 1984), pp. 1456-1458.</ref><ref name=eleven/><ref>[[Jim Falk]] (1982). ''Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power'', Oxford University Press.</ref> |

The application of [[nuclear technology]], both as a source of energy and as an instrument of war, has been controversial.<ref name=contr>Robert Benford. [http://www.jstor.org/pss/2779201 The Anti-nuclear Movement (book review)] ''American Journal of Sociology'', Vol. 89, No. 6, (May 1984), pp. 1456-1458.</ref><ref>James J. MacKenzie. [http://www.jstor.org/pss/2823429?cookieSet=1 Review of The Nuclear Power Controversy] by [[Arthur W. Murphy]] ''The Quarterly Review of Biology'', Vol. 52, No. 4 (Dec., 1977), pp. 467-468.</ref><ref name=eleven/><ref>[[Jim Falk]] (1982). ''Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power'', Oxford University Press.</ref> |

||

Scientists and diplomats have debated [[nuclear weapons]] policy since before the [[atomic bombing]] of [[Hiroshima]] in 1945.<ref>Jerry Brown and Rinaldo Brutoco (1997). ''Profiles in Power: The Anti-nuclear Movement and the Dawn of the Solar Age'', Twayne Publishers, pp. 191-192.</ref> The public became concerned about [[nuclear weapons testing]] from about 1954, following extensive nuclear testing in the [[Pacific Ocean|Pacific]]. From 1963 the [[Partial Test Ban Treaty]] prohibited atmospheric nuclear testing.<ref>Wolfgang Rudig (1990). ''Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy'', Longman, p. 54-55.</ref> |

Scientists and diplomats have debated [[nuclear weapons]] policy since before the [[atomic bombing]] of [[Hiroshima]] in 1945.<ref>Jerry Brown and Rinaldo Brutoco (1997). ''Profiles in Power: The Anti-nuclear Movement and the Dawn of the Solar Age'', Twayne Publishers, pp. 191-192.</ref> The public became concerned about [[nuclear weapons testing]] from about 1954, following extensive nuclear testing in the [[Pacific Ocean|Pacific]]. From 1963 the [[Partial Test Ban Treaty]] prohibited atmospheric nuclear testing.<ref>Wolfgang Rudig (1990). ''Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy'', Longman, p. 54-55.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 19:31, 14 February 2010

The application of nuclear technology, both as a source of energy and as an instrument of war, has been controversial.[1][2][3][4]

Scientists and diplomats have debated nuclear weapons policy since before the atomic bombing of Hiroshima in 1945.[5] The public became concerned about nuclear weapons testing from about 1954, following extensive nuclear testing in the Pacific. From 1963 the Partial Test Ban Treaty prohibited atmospheric nuclear testing.[6]

Some local opposition to nuclear power emerged in the early 1960s,[7] and in the late 1960s some members of the scientific community began to express their concerns.[8] In the early 1970s, there were large protests about a proposed nuclear power plant in Wyhl, Germany. The project was cancelled in 1975 and anti-nuclear success at Wyhl inspired opposition to nuclear power in other parts of Europe and North America.[9][10]

Nuclear power became an issue of major public protest in the 1970s.[11] In some countries, the nuclear power conflict "reached an intensity unprecedented in the history of technology controversies".[12]

Early years

In 1945 in the New Mexico desert, American scientists conducted “Trinity,” the first nuclear weapons test, marking the beginning of the atomic age.[13] Even before the Trinity test, national leaders debated the impact of nuclear weapons on domestic and foreign policy. Also involved in the debate about nuclear weapons policy was the scientific community, through professional associations such as the Federation of Atomic Scientists and the Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs.[14]

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the end of World War II quickly followed the Trinity test, and the Little Boy device was detonated over the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945. Exploding with a yield equivalent to 12,500 tonnes of TNT, the blast and thermal wave of the bomb destroyed nearly 50,000 buildings and killed approximately 75,000 people.[15] Subsequently, the world’s nuclear weapons stockpiles grew.[13]

Operation Crossroads was a series of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific Ocean in the summer of 1946. Its purpose was to test the effect of nuclear weapons on naval ships. Pressure to cancel Operation Crossroads came from scientists and diplomats. Manhattan Project scientists argued that further nuclear testing was unnecessary and environmentally dangerous. A Los Alamos study warned "the water near a recent surface explosion will be a witch's brew" of radioactivity. To prepare the atoll for the nuclear tests, Bikini's native residents were evicted from their homes and resettled on smaller, uninhabited islands where they were unable to sustain themselves.[16]

Radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing was first drawn to public attention in 1954 when a Hydrogen bomb test in the Pacific contaminated the crew of the Japanese fishing boat Lucky Dragon.[17] One of the fishermen died in Japan seven months later. The incident caused widespread concern around the world and "provided a decisive impetus for the emergence of the anti-nuclear weapons movement in many countries".[17] The anti-nuclear weapons movement grew rapidly because for many people the atomic bomb "encapsulated the very worst direction in which society was moving".[18]

Peace movements emerged in Japan and in 1954 they converged to form a unified "Japanese Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs". Japanese opposition to the Pacific nuclear weapons tests was widespread, and "an estimated 35 million signatures were collected on petitions calling for bans on nuclear weapons".[18]

In the United Kingdom, the first Aldermaston March organised by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament took place at Easter 1958, when several thousand people marched for four days from Trafalgar Square, London, to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment close to Aldermaston in Berkshire, England, to demonstrate their opposition to nuclear weapons.[19][20] The Aldermaston marches continued into the late 1960s when tens of thousands of people took part in the four-day marches.[18]

In 1959, a letter in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists was the start of a successful campaign to stop the Atomic Energy Commission dumping radioactive waste in the sea 19 kilometres from Boston.[21] In 1962, Linus Pauling won the Nobel Peace Prize for his work to stop the atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons, and the "Ban the Bomb" movement spread.[14]

The Partial Test Ban Treaty prohibited atmospheric nuclear testing after 1963. Radioactive fallout ceased to be an issue and the anti-nuclear weapons movement went into decline for some years.[17][22]

After the Partial Test Ban Treaty

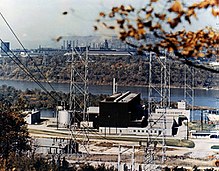

In the United States, the first commercially viable nuclear power plant was to be built at Bodega Bay, north of San Francisco, but the proposal was controversial and conflict with local citizens began in 1958.[7] The proposed plant site was close to the San Andreas Fault and close to the region's environmentally sensitive fishing and dairy industries. The Sierra Club became actively involved.[24] The conflict ended in 1964, with the forced abandonment of plans for the power plant. Historian Thomas Wellock traces the birth of the anti-nuclear movement to the controversy over Bodega Bay.[7] Attempts to build a nuclear power plant in Malibu were similar to those at Bodega Bay and were also abandoned.[7]

In 1966, Larry Bogart founded the Citizens Energy Council, a coalition of environmental groups that published the newsletters "Radiation Perils," "Watch on the A.E.C." and "Nuclear Opponents". These publications argued that "nuclear power plants were too complex, too expensive and so inherently unsafe they would one day prove to be a financial disaster and a health hazard".[25][26]

The emergence of the anti-nuclear power movement was "closely associated with the the general rise in environmental consciousness which had started to materialize in the USA in the 1960s and quickly spread to other Western industrialized countries".[27] Some nuclear experts began to voice dissenting views about nuclear power in 1969, and this was a necessary precondition for broad public concern about nuclear power to emerge.[27] These scientists included Ernest Sternglass from Pittsburg, Henry Kendall from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Nobel laureate George Wald and radiation specialist Rosalie Bertell. These members of the scientific community "by expressing their concern over nuclear power, played a crucial role in demystifying the issue for other citizens", and nuclear power became an issue of major public protest in the 1970s.[28][27]

In 1971, 15,000 people demonstrated against French plans to locate the first light-water reactor power plant in Bugey. This was the first of a series of mass protests organized at nearly every planned nuclear site in France.[29]

Also in 1971, the town of Wyhl, in Germany, was a proposed site for a nuclear power station. In the years that followed, public opposition steadily mounted, and there were large protests. Television coverage of police dragging away farmers and their wives helped to turn nuclear power into a major issue. In 1975, an administrative court withdrew the construction licence for the plant,[30][31][32] but the Wyhl occupation generated ongoing debate. This initially centred on the state government's handling of the affair and associated police behaviour, but interest in nuclear issues was also stimulated. The Wyhl experience encouraged the formation of citizen action groups near other planned nuclear sites.[30] Many other anti-nuclear groups formed elsewhere, in support of these local struggles, and some existing citizen action groups widened their aims to include the nuclear issue.[30] Anti-nuclear success at Wyhl also inspired nuclear opposition in the rest of Europe and North America.[31]

In 1972, the anti-nuclear weapons movement maintained a presence in the Pacific, largely in response to French nuclear testing there. Activists, including David McTaggart from Greenpeace, defied the French government by sailing small vessels into the test zone and interrupting the testing program.[33][34] In Australia, thousands joined protest marches in Adelaide, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Sydney. Scientists issued statements demanding an end to the tests; unions refused to load French ships, service French planes, or carry French mail; and consumers boycotted French products. In Fiji, activists formed an Against Testing on Mururoa organization.[34]

In Spain, in response to a surge in nuclear power plant proposals in the 1960s, a strong anti-nuclear movement emerged in 1973, which ultimately impeded the realisation of most of the projects.[35]

In 1974, organic farmer Sam Lovejoy took a crowbar to the weather-monitoring tower which had been erected at the Montague Nuclear Power Plant site. Lovejoy felled the tower and then took himself to the local police station, where he took full responsibility for the action. Lovejoy's action galvanized local public opinion against the plant.[36][37] The Montague project was canceled in 1980,[38] after $29 million was spent on the project.[36]

By the mid-1970s anti-nuclear activism had moved beyond local protests and politics to gain a wider appeal and influence. Although it lacked a single co-ordinating organization, and did not have uniform goals, the movement's efforts gained a great deal of attention.[3] Jim Falk has suggested that popular opposition to nuclear power quickly grew into an effective anti-nuclear power movement in the 1970s.[39] In some countries, the nuclear power conflict "reached an intensity unprecedented in the history of technology controversies".[40]

See also

References

- ^ Robert Benford. The Anti-nuclear Movement (book review) American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 89, No. 6, (May 1984), pp. 1456-1458.

- ^ James J. MacKenzie. Review of The Nuclear Power Controversy by Arthur W. Murphy The Quarterly Review of Biology, Vol. 52, No. 4 (Dec., 1977), pp. 467-468.

- ^ a b Walker, J. Samuel (2004). Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective (Berkeley: University of California Press), pp. 10-11.

- ^ Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press.

- ^ Jerry Brown and Rinaldo Brutoco (1997). Profiles in Power: The Anti-nuclear Movement and the Dawn of the Solar Age, Twayne Publishers, pp. 191-192.

- ^ Wolfgang Rudig (1990). Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy, Longman, p. 54-55.

- ^ a b c d Paula Garb. Review of Critical Masses, Journal of Political Ecology, Vol 6, 1999.

- ^ Wolfgang Rudig (1990). Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy, Longman, p. 52.

- ^ Stephen Mills and Roger Williams (1986). Public Acceptance of New Technologies Routledge, pp. 375-376.

- ^ Robert Gottlieb (2005). Forcing the Spring: The Transformation of the American Environmental Movement, Revised Edition, Island Press, USA, p. 237.

- ^ Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press, pp. 95-96.

- ^ Herbert P. Kitschelt. Political Opportunity and Political Protest: Anti-Nuclear Movements in Four Democracies British Journal of Political Science, Vol. 16, No. 1, 1986, p. 57.

- ^ a b Mary Palevsky, Robert Futrell, and Andrew Kirk. Recollections of Nevada's Nuclear Past UNLV FUSION, 2005, p. 20.

- ^ a b Jerry Brown and Rinaldo Brutoco (1997). Profiles in Power: The Anti-nuclear Movement and the Dawn of the Solar Age, Twayne Publishers, pp. 191-192.

- ^ Emsley, John (2001). "Uranium". Nature's Building Blocks: An A to Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 478. ISBN 0198503407.

- ^ Niedenthal, Jack (2008), A Short History of the People of Bikini Atoll, retrieved 2009-12-05

- ^ a b c Wolfgang Rudig (1990). Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy, Longman, p. 54-55.

- ^ a b c Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press, pp. 96-97.

- ^ A brief history of CND

- ^ "Early defections in march to Aldermaston". Guardian Unlimited. 1958-04-05.

- ^ Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press, p. 93.

- ^ Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press, p. 98.

- ^ Herbert P. Kitschelt. Political Opportunity and Political Protest: Anti-Nuclear Movements in Four Democracies British Journal of Political Science, Vol. 16, No. 1, 1986, p. 71.

- ^ Thomas Raymond Wellock (1998). Critical Masses: Opposition to Nuclear Power in California, 1958-1978, The University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 27-28.

- ^ Keith Schneider. Larry Bogart, an Influential Critic Of Nuclear Power, Is Dead at 77 The New York Times, August 20, 1991.

- ^ Anna Gyorgy (1980). No Nukes: Everyone's Guide to Nuclear Power South End Press, ISBN 0896080064, p. 383.

- ^ a b c Wolfgang Rudig (1990). Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy, Longman, p. 52.

- ^ Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press, p. 95.

- ^ Dorothy Nelkin and Michael Pollak (1982). The Atom Besieged: Antinuclear Movements in France and Germany, ASIN: B0011LXE0A, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Stephen Mills and Roger Williams (1986). Public Acceptance of New Technologies Routledge, pp. 375-376.

- ^ a b Robert Gottlieb (2005). Forcing the Spring: The Transformation of the American Environmental Movement, Revised Edition, Island Press, USA, p. 237.

- ^ Nuclear Power in Germany: A Chronology

- ^ Paul Lewis. David McTaggart, a Builder of Greenpeace, Dies at 69 The New York Times, March 24, 2001.

- ^ a b Lawrence S. Wittner. Nuclear Disarmament Activism in Asia and the Pacific, 1971-1996 The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 25-5-09, June 22, 2009.

- ^ Lutz Mez, Mycle Schneider and Steve Thomas (Eds.) (2009). International Perspectives of Energy Policy and the Role of Nuclear Power, Multi-Science Publishing Co. Ltd, p. 371.

- ^ a b Utilites Drop Nuclear Power Plant Plans Ocala Star-Banner, January 4, 1981.

- ^ Anna Gyorgy (1980). No Nukes: Everyone's Guide to Nuclear Power South End Press, ISBN 0896080064, pp. 393-394.

- ^ Northeast Utilites System. Some of the Major Events in NU's History Since the 1966 Affiliation

- ^ Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press, p. 96.

- ^ Herbert P. Kitschelt. Political Opportunity and Political Protest: Anti-Nuclear Movements in Four Democracies British Journal of Political Science, Vol. 16, No. 1, 1986, p. 57.