Anti-nuclear movement: Difference between revisions

→Roots of the movement: expanding |

|||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

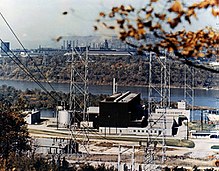

[[Image: Shippingport Reactor.jpg|thumb|The [[Shippingport Atomic Power Station]] was the first full-scale PWR nuclear power plant in the United States. The reactor went online December 2, 1957, and was in operation until October, 1982.]] |

[[Image: Shippingport Reactor.jpg|thumb|The [[Shippingport Atomic Power Station]] was the first full-scale PWR nuclear power plant in the United States. The reactor went online December 2, 1957, and was in operation until October, 1982.]] |

||

{{See also|Debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki}} |

{{See also|Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki|Debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki}} |

||

The application of [[nuclear technology]], both as a source of energy and as an instrument of war, has been controversial.<ref name=contr>Robert Benford. [http://www.jstor.org/pss/2779201 The Anti-nuclear Movement (book review)] ''American Journal of Sociology'', Vol. 89, No. 6, (May 1984), pp. 1456-1458.</ref><ref name=eleven/><ref>[[Jim Falk]] (1982). ''Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power'', Oxford University Press.</ref> |

The application of [[nuclear technology]], both as a source of energy and as an instrument of war, has been controversial.<ref name=contr>Robert Benford. [http://www.jstor.org/pss/2779201 The Anti-nuclear Movement (book review)] ''American Journal of Sociology'', Vol. 89, No. 6, (May 1984), pp. 1456-1458.</ref><ref name=eleven/><ref>[[Jim Falk]] (1982). ''Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power'', Oxford University Press.</ref> |

||

In 1945 in the [[New Mexico]] desert, American scientists conducted “[[Trinity (nuclear test)|Trinity]],” the first [[nuclear weapons test]], marking the beginning of the [[atomic age]].<ref name=pal/> Even before the Trinity test, national leaders debated the impact of nuclear weapons on domestic and foreign policy. |

In 1945 in the [[New Mexico]] desert, American scientists conducted “[[Trinity (nuclear test)|Trinity]],” the first [[nuclear weapons test]], marking the beginning of the [[atomic age]].<ref name=pal/> Even before the Trinity test, national leaders debated the impact of nuclear weapons on domestic and foreign policy. Also involved in the debate about nuclear weapons policy was the scientific community, through professional associations such as the [[Federation of Atomic Scientists]] and the [[Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs]].<ref name=brow/> |

||

The [[atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki]] and the end of World War II quickly followed the Trinity test, and the [[Little Boy]] device was detonated over the [[Japan]]ese city of [[Hiroshima]] on 6 August 1945. Exploding with a yield equivalent to 12,500 tonnes of [[Trinitrotoluene|TNT]], the blast and thermal wave of the bomb destroyed nearly 50,000 buildings and killed approximately 75,000 people.<ref>{{Cite book |year=2001 |chapter=Uranium |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=j-Xu07p3cKwC&printsec=frontcover |title=Nature's Building Blocks: An A to Z Guide to the Elements |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |location=[[Oxford]] |isbn=0198503407 |authorlink=John Emsley |first=John |last=Emsley |pages=478 }}</ref> The world’s nuclear weapons stockpiles grew.<ref name=pal>Mary Palevsky, Robert Futrell, and Andrew Kirk. [http://research.unlv.edu/innovation/issues/summer2005/pdf/nuclearpast.pdf Recollections of Nevada's Nuclear Past] ''UNLV FUSION'', 2005, p. 20.</ref> |

|||

Radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing was first drawn to public attention in 1954 when a Hydrogen bomb test in the Pacific contaminated the crew of the Japanese fishing boat ''[[Lucky Dragon]]''.<ref name=rudig2/> One of the fishermen died in Japan seven months later. The incident caused widespread concern around the world and "provided a decisive impetus for the emergence of the anti-nuclear weapons movement in many countries".<ref name=rudig2>Wolfgang Rudig (1990). ''Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy'', Longman, p. 54-55.</ref> The anti-nuclear weapons movement grew rapidly because for many people the atomic bomb "encapsulated the very worst direction in which society was moving".<ref name=falkj>Jim Falk (1982). ''Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power'', Oxford University Press, pp. 96-97.</ref> |

Radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing was first drawn to public attention in 1954 when a Hydrogen bomb test in the Pacific contaminated the crew of the Japanese fishing boat ''[[Lucky Dragon]]''.<ref name=rudig2/> One of the fishermen died in Japan seven months later. The incident caused widespread concern around the world and "provided a decisive impetus for the emergence of the anti-nuclear weapons movement in many countries".<ref name=rudig2>Wolfgang Rudig (1990). ''Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy'', Longman, p. 54-55.</ref> The anti-nuclear weapons movement grew rapidly because for many people the atomic bomb "encapsulated the very worst direction in which society was moving".<ref name=falkj>Jim Falk (1982). ''Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power'', Oxford University Press, pp. 96-97.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 06:33, 8 February 2010

The anti-nuclear movement is a social movement that opposes the use of various nuclear technologies. Many direct action groups, environmental groups, and professional organisations have identified themselves with the movement at the local, national, and international level. Major anti-nuclear groups include Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace, International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, and the Nuclear Information and Resource Service. The initial objective of the anti-nuclear movement was nuclear disarmament. Later the focus began to shift to other issues, mainly opposition to the use of nuclear power.

There have been many large anti-nuclear demonstrations and protests. A protest against nuclear power occurred in July 1977 in Bilbao, Spain, with up to 200,000 people in attendance. Following the Three Mile Island accident in 1979, an anti-nuclear protest was held in New York City, involving 200,000 people. In 1981, Germany's largest anti-nuclear power demonstration took place to protest against the Brokdorf Nuclear Power Plant west of Hamburg; some 100,000 people came face to face with 10,000 police officers. The largest anti-nuclear protest was a 1983 nuclear weapons protest in West Berlin which had about 600,000 participants. In May 1986, following the Chernobyl disaster, an estimated 150,000 to 200,000 people marched in Rome to protest against the Italian nuclear program.

For many years after the 1986 Chernobyl disaster nuclear power was off the policy agenda in most countries, and the anti-nuclear power movement seemed to have won its case. Some anti-nuclear groups disbanded. More recently, however, following public relations activities by the nuclear industry, and concerns about climate change, nuclear power issues have come back into energy policy discussions in some countries. Anti-nuclear activity has increased correspondingly and most countries in the world have no nuclear power stations and no plans to develop nuclear power.

History and issues

Roots of the movement

The application of nuclear technology, both as a source of energy and as an instrument of war, has been controversial.[1][2][3]

In 1945 in the New Mexico desert, American scientists conducted “Trinity,” the first nuclear weapons test, marking the beginning of the atomic age.[4] Even before the Trinity test, national leaders debated the impact of nuclear weapons on domestic and foreign policy. Also involved in the debate about nuclear weapons policy was the scientific community, through professional associations such as the Federation of Atomic Scientists and the Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs.[5]

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the end of World War II quickly followed the Trinity test, and the Little Boy device was detonated over the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945. Exploding with a yield equivalent to 12,500 tonnes of TNT, the blast and thermal wave of the bomb destroyed nearly 50,000 buildings and killed approximately 75,000 people.[6] The world’s nuclear weapons stockpiles grew.[4]

Radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing was first drawn to public attention in 1954 when a Hydrogen bomb test in the Pacific contaminated the crew of the Japanese fishing boat Lucky Dragon.[7] One of the fishermen died in Japan seven months later. The incident caused widespread concern around the world and "provided a decisive impetus for the emergence of the anti-nuclear weapons movement in many countries".[7] The anti-nuclear weapons movement grew rapidly because for many people the atomic bomb "encapsulated the very worst direction in which society was moving".[8]

Peace movements emerged in Japan and in 1954 they converged to form a unified "Japanese Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs". Japanese opposition to the Pacific nuclear weapons tests was widespread, and "an estimated 35 million signatures were collected on petitions calling for bans on nuclear weapons".[8]

In the United Kingdom, the first Aldermaston March organised by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament took place at Easter 1958, when several thousand people marched for four days from Trafalgar Square, London, to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment close to Aldermaston in Berkshire, England, to demonstrate their opposition to nuclear weapons.[9][10] The Aldermaston marches continued into the late 1960s when tens of thousands of people took part in the four-day marches.[8]

In 1959, a letter in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists was the start of a successful campaign to stop the Atomic Energy Commission dumping radioactive waste in the sea 19 kilometres from Boston.[11] In 1962, Linus Pauling won the Nobel Peace Prize for his work to stop the atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons, and the "Ban the Bomb" movement spread.[5]

The Partial Test Ban Treaty prohibited atmospheric nuclear testing after 1963. Radioactive fallout ceased to be an issue and the anti-nuclear weapons movement went into decline for some years.[7][12]

In the United States, the first commercially viable nuclear power plant was to be built at Bodega Bay, north of San Francisco, but the proposal was controversial and conflict with local citizens began in 1958.[13] The proposed plant site was close to the San Andreas Fault and close to the region's environmentally sensitive fishing and dairy industries. The Sierra Club became actively involved.[14] The conflict ended in 1964, with the forced abandonment of plans for the power plant. Historian Thomas Wellock traces the birth of the anti-nuclear movement to the controversy over Bodega Bay.[13] Attempts to build a nuclear power plant in Malibu were similar to those at Bodega Bay and were also abandoned.[13]

In 1966, Larry Bogart founded the Citizens Energy Council, a coalition of environmental groups that published the newsletters "Radiation Perils," "Watch on the A.E.C." and "Nuclear Opponents". These publications argued that "nuclear power plants were too complex, too expensive and so inherently unsafe they would one day prove to be a financial disaster and a health hazard".[15][16]

The emergence of the anti-nuclear power movement was "closely associated with the the general rise in environmental consciousness which had started to materialize in the USA in the 1960s and quickly spread to other Western industrialized countries".[17] Some nuclear experts began to voice dissenting views about nuclear power in 1969, and this was a necessary precondition for broad public concern about nuclear power to emerge.[17] These scientists included Ernest Sternglass from Pittsburg, Henry Kendall from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Nobel laureate George Wald and radiation specialist Rosalie Bertell. These members of the scientific community "by expressing their concern over nuclear power, played a crucial role in demystifying the issue for other citizens", and nuclear power became an issue of major public protest in the 1970s.[18][17]

In 1971, 15,000 people demonstrated against French plans to locate the first light-water reactor power plant in Bugey. This was the first of a series of mass protests organized at nearly every planned nuclear site in France.[19]

Also in 1971, the town of Wyhl, in Germany, was a proposed site for a nuclear power station. In the years that followed, public opposition steadily mounted, and there were large protests. Television coverage of police dragging away farmers and their wives helped to turn nuclear power into a major issue. In 1975, an administrative court withdrew the construction licence for the plant,[20][21][22] but the Wyhl occupation generated ongoing debate. This initially centred on the state government's handling of the affair and associated police behaviour, but interest in nuclear issues was also stimulated. The Wyhl experience encouraged the formation of citizen action groups near other planned nuclear sites.[20] Many other anti-nuclear groups formed elsewhere, in support of these local struggles, and some existing citizen action groups widened their aims to include the nuclear issue.[20] Anti-nuclear success at Wyhl also inspired nuclear opposition in the rest of Europe and North America.[21]

In 1972, the anti-nuclear weapons movement maintained a presence in the Pacific, largely in response to French nuclear testing there. Activists, including David McTaggart from Greenpeace, defied the French government by sailing small vessels into the test zone and interrupting the testing program.[23][24] In Australia, thousands joined protest marches in Adelaide, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Sydney. Scientists issued statements demanding an end to the tests; unions refused to load French ships, service French planes, or carry French mail; and consumers boycotted French products. In Fiji, activists formed an Against Testing on Mururoa organization.[24]

In Spain, in response to a surge in nuclear power plant proposals in the 1960s, a strong anti-nuclear movement emerged in 1973, which ultimately impeded the realisation of most of the projects.[25]

By the mid-1970s anti-nuclear activism had moved beyond local protests and politics to gain a wider appeal and influence. Although it lacked a single co-ordinating organization, and did not have uniform goals, the movement's efforts gained a great deal of attention.[2] Jim Falk has suggested that popular opposition to nuclear power quickly grew into an effective anti-nuclear power movement in the 1970s.[26]

Anti-nuclear concerns

Anti-nuclear groups believe that nuclear power poses multiple threats to people and the environment. These include health risks and environmental damage from uranium mining, processing and transport, the risk of nuclear weapons proliferation, the unsolved problem of nuclear waste, and the possibility of further serious accidents.[27][28] Anti-nuclear critics see nuclear power as a dangerous, expensive way to boil water to generate electricity.[29]

Opponents of nuclear energy make connections between the international export and development of nuclear power technologies and the proliferation of nuclear weapons. The facilities and expertise to produce nuclear power can be readily adapted to produce nuclear weapons.[30][31] Greenpeace suggests that nuclear power and nuclear weapons have grown up like Siamese twins. Since international controls on nuclear proliferation began, Israel, India, Pakistan and North Korea have all obtained nuclear weapons, demonstrating the link with nuclear power programs.[27]

Nuclear power plants are very expensive.[30][32] Making reliable cost estimates is difficult, and estimates for new reactors in the USA range from $5 billion to $10 billion per unit. Building nuclear plants is seen to be "a risky business", according to several notable credit rating agencies and investment analysts.[32]

Because nuclear power has always been a technology which requires and employs specialists, some individuals view it as an elitist technology.[33] Nuclear power is centralised energy, in both a physical and political sense. It allows a small number of scientific, political and economic elites to make key decisions about energy.[30]

Nuclear power plants are some of the most sophisticated and complex energy systems ever designed.[34][35][36] Any complex system, no matter how well it is designed and engineered, cannot be deemed failure-proof. This is especially true if people are required to operate controls that dictate how the system functions.[37] Stephanie Cooke has reported that:

The reactors themselves were enormously complex machines with an incalculable number of things that could go wrong. When that happened at Three Mile Island in 1979, another fault line in the nuclear world was exposed. One malfunction led to another, and then to a series of others, until the core of the reactor itself began to melt, and even the world's most highly trained nuclear engineers did not know how to respond. The accident revealed serious deficiencies in a system that was meant to protect public health and safety.[38]

Nuclear accidents are often cited by anti-nuclear groups as evidence of the inherent danger of nuclear power.[30] The worst nuclear accident in history is the Chernobyl disaster. Other serious nuclear and radiation accidents include the Mayak disaster, Soviet submarine K-431 accident, Soviet submarine K-19 accident, Chalk River accidents, Windscale fire, Costa Rica radiotherapy accident, Zaragoza radiotherapy accident, Goiania accident, Church Rock Uranium Mill Spill and the SL-1 accident.[39][40]

Greenpeace contends that the risks from operating nuclear reactors are increasing and the likelihood of an accident is now higher than ever:

Most of the world’s reactors are more than 20 years old and therefore more prone to age related failures. Many utilities are attempting to extend their life from the 40 years or so they were originally designed for to around 60 years, posing new risks.[27]

New so-called passively safe reactors have many safety systems replaced by ‘natural’ processes, such as gravity fed emergency cooling water and air cooling. This can make them more vulnerable to terrorist attack.[27]

Especially since the September 11 attacks, people have become concerned that terrorists or criminals could bomb a nuclear plant and release radioactive material. Building more plants would create more targets to protect.[32][30]

There is an "international consensus on the advisability of storing nuclear waste in deep underground repositories",[41] but no country in the world has yet opened such a site.[41][42][43][44][45] The demise of the proposed Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository in Nevada leaves the USA with no plan for the long-term storage of spent nuclear fuel.[32]

Since 2000 the nuclear industry has undertaken an international media and lobbying campaign to promote nuclear power as a solution to the enhanced greenhouse effect and climate change. Nuclear power, the industry claims, emits no or negligible amounts of carbon dioxide. Anti-nuclear groups respond by saying that only reactor operation is free of carbon dioxide emissions. All other stages of the nuclear fuel chain – mining, milling, fuel fabrication, enrichment, reactor construction, decommissioning and waste management – use fossil fuels and hence emit carbon dioxide.[46][47] At the same time, global warming puts nuclear plants at risk, with some reactors being shut down "due to summer heat waves and droughts that impact their cooling systems".[48]

Some anti-nuclear groups also oppose research into nuclear fusion power.[49]

Nuclear-free alternatives

Anti-nuclear groups generally claim that reliance on nuclear energy can be reduced by adopting energy conservation and energy efficiency measures. Energy efficiency can reduce the consumption of energy while providing the same level of energy "services".[27]

Anti-nuclear groups also favour the use of renewable energy, such as wind power, solar power, geothermal energy and biofuel.[50] According to the International Energy Agency, renewable energy technologies are essential contributors to the energy supply portfolio, as they contribute to world energy security, reduce dependency on fossil fuels, and provide opportunities for mitigating greenhouse gases.[51] Fossil fuels are being replaced by clean, climate-stabilizing, non-depletable sources of energy:

...the transition from coal, oil, and gas to wind, solar, and geothermal energy is well under way. In the old economy, energy was produced by burning something — oil, coal, or natural gas — leading to the carbon emissions that have come to define our economy. The new energy economy harnesses the energy in wind, the energy coming from the sun, and heat from within the earth itself.[52]

Greenpeace advocates reduction of fossil fuels by 50% by 2050 as well as phasing out nuclear energy, contending that innovative technologies can increase energy efficiency, and suggests that by 2050 the majority of electricity will be generated from renewable sources.[50] The International Energy Agency estimates that nearly 50% of global electricity supplies will need to come from renewable energy sources in order to halve carbon dioxide emissions by 2050 and minimise significant, irreversible climate change impacts.[53]

Anti-nuclear organisations

The anti-nuclear movement is a social movement which operates at the local, national, and international level. Various types of groups have identified themselves with the movement:[54]

- direct action groups, such as the Clamshell Alliance and Shad Alliance;

- environmental groups, such as Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace;

- consumer protection groups, such as Ralph Nader's Critical Mass;

- professional organisations,[55] such as Union of Concerned Scientists and International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War; and

- political parties such as European Free Alliance.

Anti-nuclear power organisations have emerged in every country that has had a nuclear power programme. Protest movements against nuclear power first emerged in the USA, at the local level, and spread quickly to Europe and the rest of the world. National nuclear campaigns emerged in the late 1970s. Fuelled by the Three Mile Island accident and the Chernobyl disaster, the anti-nuclear power movement mobilised political and economic forces which for some years made nuclear power untenable in many countries.[56]

Some of these anti-nuclear power organisations are reported to have developed considerable expertise on nuclear power and energy issues.[57] In 1992, the chairman of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission said that "his agency had been pushed in the right direction on safety issues because of the pleas and protests of nuclear watchdog groups".[58]

International organisations

- Friends of the Earth

- Greenpeace

- International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons

- International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War

- Nuclear Information and Resource Service

- Ploughshares Fund

- World Union for Protection of Life

National and local

- Anti-nuclear movement in Africa

- Anti-nuclear movement in Australia

- Anti-nuclear movement in Austria

- Anti-nuclear movement in Canada

- Anti-nuclear movement in the European Union

- Anti-nuclear movement in Japan

- Anti-nuclear movement in Kazakhstan

- Anti-nuclear movement in New Zealand

- Anti-nuclear movement in the Philippines

- Anti-nuclear movement in Russia

- Anti-nuclear movement in Spain

- Anti-nuclear movement in Switzerland

Symbols

-

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament symbol, designed in 1958. It later became a universal peace symbol used in many different versions worldwide.[59]

-

The "Smiling Sun" icon of the anti-nuclear movement which came from the Danish anti-nuclear movement.[60][failed verification]

-

Another high profile anti-nuclear symbol, which is a variation on the international radiation symbol.

-

Anti-nuclear poster from the 1970s American movement.

Activities

Large protests

In 1971, 15,000 people demonstrated against French plans to locate the first light-water reactor power plant in Bugey. This was the first of a series of mass protests organized at nearly every planned nuclear site in France until the massive demonstration at the Superphénix breeder reactor in Creys-Malvillein in 1977 culminated in violence.[19]

On July 14, 1977, in Bilbao, Spain, 150,000 to 200,000 people protested against the Lemoniz Nuclear Power Plant. This has been called the "biggest ever anti-nuclear demonstration".[61]

In the Philippines, a focal point for protests in the late 1970s and 1980s was the proposed Bataan Nuclear Power Plant, which was built but never operated.[62] The project was criticised for being a potential threat to public health, especially since the plant was located in an earthquake zone.[62]

In 1981, Germany's largest anti-nuclear power demonstration took place to protest against the construction of the Brokdorf Nuclear Power Plant on the North Sea coast west of Hamburg. Some 100,000 people came face to face with 10,000 police officers. Twenty-one policemen were injured by demonstrators armed with gasoline bombs, sticks, stones and high-powered slingshots.[63][64][65]

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the revival of the nuclear arms race, accompanied by "glib talk of nuclear war", triggered a new wave of protests about nuclear weapons. Older organizations such as the Federation of Atomic Scientists revived, and newer organizations appeared, including the Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign and Physicians for Social Responsibility.[66] Beginning in 1982, an annual series of Christian peace vigils called the "Lenten Desert Experience" were held over a period of several weeks at a time, at the entrance to the Nevada Test Site in the USA. This led to a faith-based aspect of the nuclear disarmament movement and the formation of the anti-nuclear Nevada Desert Experience group.[67] The largest anti-nuclear protest was most likely a 1983 nuclear weapons protest in West Berlin which had about 600,000 participants.[68] In the UK, on 1 April 1983, about 70,000 people linked arms to form a human chain between three nuclear weapons centres in Berkshire. The anti-nuclear demonstration stretched for 14 miles along the Kennet Valley.[69]

On Palm Sunday 1982, an estimated 100,000 Australians participated in anti-nuclear rallies in the nation's largest cities. Growing year by year, the rallies drew 350,000 participants in 1985.[24] The movement focused on halting Australia's uranium mining and exports, abolishing nuclear weapons, removing foreign military bases from Australia's soil, and creating a nuclear-free Pacific.[24]

In May 1986, following the Chernobyl disaster, clashes between anti-nuclear protesters and West German police became common. More than 400 people were injured in mid-May at the site of a nuclear-waste reprocessing plant being built near Wackersdorf. Police "used water cannons and dropped tear-gas grenades from helicopters to subdue protesters armed with slingshots, crowbars and Molotov cocktails".[70] Also in May 1986, an estimated 150,000 to 200,000 people marched in Rome to protest against the Italian nuclear program, and 50,000 marched in Milan.[71] Hundreds of people walked from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C. in 1986 in what is referred to as the Great Peace March for Global Nuclear Disarmament. The march took nine months to traverse 3,700 miles (6,000 km), advancing approximately fifteen miles per day.[72]

The anti-nuclear organisation "Nevada Semipalatinsk" was formed in 1989 and was one of the first major anti-nuclear groups in the former Soviet Union. It attracted thousands of people to its protests and campaigns which eventually led to the closure of the nuclear test site at Semipalatinsk, in north-east Kazakhstan, in 1991. The Soviet Union conducted over 400 nuclear weapons tests at the Semipalatinsk Test Site between 1949 and 1989.[73] The United Nations believes that one million people were exposed to radiation and babies are still being born with genetic abnormalities in towns and villages around Semipalatinsk.[74][75][76]

The largest anti-nuclear petition was against nuclear weapons and had 32 million signatures.[77]

Protests in the United States

The American public were concerned about the release of radioactive gas from the Three Mile Island accident in 1979 and many mass demonstrations took place across the country in the following months. The largest one was held in New York City in September 1979 and involved two hundred thousand people; speeches were given by Jane Fonda and Ralph Nader.[78][79][80]

On May 2, 1977, 1,414 Clamshell Alliance protesters were arrested at Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant.[81][82] The protesters who were arrested were charged with criminal trespass and asked to post bail ranging from $100 to $500. They refused and were then held in five national guard armories for 12 days. The Seabrook conflict, and role of New Hampshire Governor Meldrim Thomson, received much national media coverage.[83]

Other notable anti-nuclear protests in the United States have included:

- June 1978: some 12,000 people attended a protest at Seabrook.[82]

- August 1978: almost 500 Abalone Alliance protesters were arrested at Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant.[84]

- April 8, 1979: 30,000 people marched in San Francisco to support shutting down the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant.[85]

- April 28, 1979: 15,000 people demonstrated against the Rocky Flats Nuclear Processing Plant in Colorado, making the link between nuclear power and nuclear weaponry.[86][87]

- May 1979: An estimated 65,000 people, including the Governor of California, attended a march and rally against nuclear power in Washington, D.C.[85][79]

- June 2, 1979: about 500 people were arrested for protesting about construction of the Black Fox Nuclear Power Plant in Oklahoma.[82][88]

- June 3, 1979: following the Three Mile Island accident, some 15,000 people attended a rally organized by the Shad Alliance and about 600 were arrested at Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant in New York.[89]

- June 30, 1979: about 40,000 people attended a protest rally at Diablo Canyon.[90]

- June 22, 1980: about 15,000 people attended a protest near San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station in California.[82]

- 1997: Over 2,000 people turned out for a demonstration at the Nevada Test Site and 700 were arrested.[91]

- May 1, 2005: 40,000 anti-nuclear/anti-war protesters march past the UN in New York, 60 years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[92][93]

Anti-nuclear protests preceded the shutdown of the Shoreham, Yankee Rowe, Millstone I, Rancho Seco, Maine Yankee, and about a dozen other nuclear power plants.[94]

Other events

A few injuries have occurred during anti-nuclear protests:

- On 10 July 1985, the flagship of Greenpeace, Rainbow Warrior, was sunk by French agents in New Zealand waters, and a Greenpeace photographer was killed. The ship was involved in protests against nuclear weapons testing at Mururoa Atoll. The French Government initially denied any involvement with the sinking but eventually admitted its guilt in October 1985. Two French agents pleaded guilty to charges of manslaughter and the French Government paid $7 million in damages.[95]

- In 1990, two pylons holding high voltage power lines connecting the French and Italian grid were blown up by Italian eco-terrorists, and the attack is believed to have been directly in opposition against the Superphénix.[96]

- In 2004, a 23 year old activist who had tied himself to train tracks in front of a shipment of reprocessed nuclear waste was run over by the wheels of the train. The event happened in Avricourt, France and the fuel (totaling 12 containers) was from a German plant, on its way to be reprocessed.[97]

- On July 21, 2007, a Russian antinuclear activist was killed in a protest outside a future Uranium enrichment site. The victim was sleeping in a peace camp, which was part of the protest when it was attacked by unidentified raiders who beat activists who were sleeping, injuring eight and killing one. The protest group was self identified as anarchist and the assailants were suspected to be right wing.[98]

Recent developments

For many years after the 1986 Chernobyl disaster nuclear power was off the policy agenda in most countries, and the anti-nuclear power movement seemed to have won its case.[99][100] Some anti-nuclear groups disbanded.[100] More recently, however, following intense public relations activities by the nuclear industry, and concerns about climate change, nuclear power issues have come back into energy policy discussions in some countries.[99] Anti-nuclear activity has increased correspondingly.

In January 2004, up to 15,000 anti-nuclear protesters marched in Paris against a new generation of nuclear reactors, the European Pressurised Water Reactor (EPWR).[101]

On May 1, 2005, 40,000 anti-nuclear/anti-war protesters marched past the United Nations in New York, 60 years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[102][103] This was the largest anti-nuclear rally in the U.S. for several decades.[104] In Britain, there were many protests about the government's proposal to replace the aging Trident weapons system with a newer model. The largest protest had 100,000 participants and, according to polls, 59 percent of the public opposed the move.[104]

On March 17, 2007 simultaneous protests, organised by Sortir du nucléaire, were staged in five French towns to protest construction of EPR plants; Rennes, Lyon, Toulouse, Lille, and Strasbourg.[105][106]

During a weekend in October 2008, some 15,000 people disrupted the transport of radioactive nuclear waste from France to a dump in Germany. This was one of the largest such protests in many years and, according to Der Spiegel, it signals a revival of the anti-nuclear movement in Germany.[107][108][109] In 2009, the coalition of green parties in the European parliament, who are unanimous in their anti-nuclear position, increased their presence in the parliament from 5.5% to 7.1% (52 seats).[110]

In October 2008 in the United Kingdom, more than 30 people were arrested during one of the largest anti-nuclear protests at the Atomic Weapons Establishment at Aldermaston for 10 years. The demonstration marked the start of the UN World Disarmament Week and involved about 400 people.[111]

In 2008 and 2009, there have been protests about, and criticism of, several new nuclear reactor proposals in the United States.[112][113][114] There have also been some objections to license renewals for existing nuclear plants.[115][116]

A convoy of 350 farm tractors and 50,000 protesters took part in an anti-nuclear rally in Berlin on September 5, 2009. The marchers demanded that Germany close all nuclear plants by 2020 and close the Gorleben radioactive dump.[117][118] Gorleben is the focus of the anti-nuclear movement in Germany, which has tried to derail train transports of waste and to destroy or block the approach roads to the site. Two above-ground storage units house 3,500 containers of radioactive sludge and thousands of tonnes of spent fuel rods.[119]

Impact

Impact on popular culture

Beginning in the 1960s, anti-nuclear ideas received coverage in the popular media with novels such as Fail-Safe and feature films such as Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), The China Syndrome (1979), Silkwood (1983), and The Rainbow Warrior (1992).

Dr. Strangelove explored "what might happen within the Pentagon ... if some maniac Air Force general should suddenly order a nuclear attack on the Soviet Union". One reviewer called the movie "one of the cleverest and most incisive satiric thrusts at the awkwardness and folly of the military that has ever been on the screen".[120]

The China Syndrome has been described as a "gripping 1979 drama about the dangers of nuclear power" which had an extra impact when the real-life accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant occurred several weeks after the film opened. Jane Fonda plays a TV reporter who witnesses a near-meltdown (the "China syndrome" of the title) at a local nuclear plant, which was averted by a quick-thinking engineer, played by Jack Lemmon. The plot suggests that corporate greed and cost-cutting "have led to potentially deadly faults in the plant's construction".[121]

Silkwood was inspired by the true-life story of Karen Silkwood, who died in a suspicious car accident while investigating alleged wrongdoing at the Kerr-McGee plutonium plant where she worked.[1]

Musicians United for Safe Energy (MUSE) was a musical group founded in 1979 by Jackson Browne, Graham Nash, Bonnie Raitt, and John Hall, following the Three Mile Island nuclear accident. The group organized a series of five No Nukes concerts held at Madison Square Garden in New York City in September 1979. On September 23, 1979, almost 200,000 people attended a large anti-nuclear rally staged by MUSE on the then-empty north end of the Battery Park City landfill in New York.[122] The album No Nukes, and a film, also titled No Nukes, were both released in 1980 to document the performances.

In 2007, Bonnie Raitt, Graham Nash, and Jackson Browne, as part of the No Nukes group, recorded a music video of the Buffalo Springfield song "For What It's Worth".[123][124]

Impact on policy

Historian Lawrence S. Wittner has argued that anti-nuclear sentiment and activism led directly to government policy shifts about nuclear weapons. Public opinion influenced policymakers by limiting their options and also by forcing them to follow certain policies over others. Wittner credits public pressure and anti-nuclear activism with "Truman’s decision to explore the Baruch Plan, Eisenhower’s efforts towards a nuclear test ban and the 1958 testing moratorium, and Kennedy’s signing of the Partial Test Ban Treaty".[125]

In terms of nuclear power, Forbes magazine, in the September 1975 issue, reported that "the anti-nuclear coalition has been remarkably successful ... [and] has certainly slowed the expansion of nuclear power."[2] California has banned the approval of new nuclear reactors since the late 1970s because of concerns over waste disposal,[126] and some other U.S. states have a moratorium on construction of nuclear power plants.[127] A total of 63 nuclear units were canceled in the USA between 1975 and 1980.[128]

The proliferation of nuclear weapons became a presidential priority issue for the Carter Administration in the late 1970s.[129] To deal with proliferation problems, President Carter promoted stronger international control over nuclear technology, including nuclear reactor technology. Although a strong supporter of nuclear power generally, Carter turned against the breeder reactor lest the plutonium it produced be diverted into nuclear weapons.[129]

For many years after the 1986 Chernobyl disaster nuclear power was off the policy agenda in most countries. In recent years, intense public relations activities by the nuclear industry, increasing evidence of climate change and failures to address it, have brought nuclear power issues back to the forefront of policy discussion in the nuclear renaissance countries.[99][47] But some countries are not prepared to expand nuclear power and are still divesting themselves of their nuclear legacy.[99]

Under the New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act 1987, all territorial sea and land of New Zealand is declared a nuclear free zone. Nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed ships are prohibited from entering the country's territorial waters. Dumping of foreign radioactive waste and development of nuclear weapons in the country is outlawed.[130] Despite common misconception, this act does not make nuclear power plants illegal.[131] A 2008 survey shows that 19 % of New Zealanders favour nuclear power as the best energy source, while 77% prefer wind power as the best energy source.[132]

In Italy the use of nuclear power was barred by a referendum in 1987.[133] Recently, however, Italy has agreed to export nuclear technology[134] and now intends to restart its civil nuclear power program.[135]

Touted as a victory by the Alliance '90/The Greens political party, which positions itself as anti-nuclear, Germany set a date of 2020 for the permanent shutdown of the last nuclear power plant in the Nuclear Exit Law, although recently there have been discussions about extending this date or repealing the law.[135][136]

Ireland has no plans to change its non-nuclear stance and pursue nuclear power in the future.[137]

In the United States, the Navajo Nation forbids uranium mining and processing in its land.[138]

In the United States, a 2007 University of Maryland survey showed that 73 percent of the public surveyed favours the elimination of all nuclear weapons, 64 percent support removing all nuclear weapons from high alert, and 59 percent support reducing U.S. and Russian nuclear stockpiles to 400 weapons each. Given the unpopularity of nuclear weapons, U.S. politicians have been wary of supporting new nuclear programs. Republican-dominated congresses "have defeated the Bush administration's plan to build so-called 'bunker-busters' and 'mini-nukes'."[104]

As of 2010, Australia has no nuclear power stations and the current Rudd Labor government is opposed to nuclear power for Australia.[139] Australia also has no nuclear weapons.

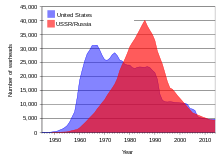

Thirty-one countries operate nuclear power plants.[140] Nine nations possess nuclear weapons:[141]

Today, some 26,000 nuclear weapons remain in the arsenals of the nine nuclear powers, with thousands on hair-trigger alert. Although U.S., Russian, and British nuclear arsenals are shrinking in size, those in the four Asian nuclear nations—China, India, Pakistan, and North Korea—are growing, in large part because of tensions among them. This Asian arms race also has possibilities of bringing Japan into the nuclear club.[24]

During Barack Obama's successful U.S. presidential election campaign, he advocated the abolition of nuclear weapons. Since his election he has reiterated this goal in several major policy addresses.[24]

Public opinion surveys on nuclear issues

In 2005, the International Atomic Energy Agency presented the results of a series of public opinion surveys in the Global Public Opinion on Nuclear Issues report.[142] Majorities of respondents in 14 of the 18 countries surveyed believe that the risk of terrorist acts involving radioactive materials and nuclear facilities is high, because of insufficient protection. While majorities of citizens generally support the continued use of existing nuclear power reactors, most people do not favour the building of new nuclear plants, and some people feel that all nuclear power plants should be closed down.[142] Stressing the climate change benefits of nuclear energy positively influences some people to be more supportive of expanding the role of nuclear power in the world, but there is still a general reluctance to support the building of more nuclear power plants.[142]

In the United States, the Nuclear Energy Institute has run polls since the 1980s. A poll in conducted March 30 to April 1, 2007 chose solar as the most likely largest source for electricity in the US in 15 years (27% of those polled) followed by nuclear, 24% and coal, 14%. Those who were favourable of nuclear being used dropped to 63% from a historic high of 70% in 2005 and 68% in September, 2006.[143]

A CBS News/New York Times poll in 2007 showed that a majority of Americans would not like to have a nuclear plant built in their community, although an increasing percentage would like to see more nuclear power.[144]

The two fuel sources that attracted the highest levels of support in the 2007 MIT Energy Survey are solar power and wind power. Outright majorities would choose to “increase a lot” use of these two fuels, and better than three out of four Americans would like to increase these fuels in the U. S. energy portfolio. Fourteen per cent of respondents would like to see nuclear power "increase a lot".[145]

A poll in the European Union for Feb-Mar 2005 showed 37% in favour of nuclear energy and 55% opposed, leaving 8% undecided.[146] The same agency ran another poll in Oct-Nov 2006 that showed 14% favoured building new nuclear plants, 34% favoured maintaining the same number, and 39% favoured reducing the number of operating plants, leaving 13% undecided. This poll showed that the approval of nuclear power rose with the education level of respondents.[147]

A September 2007 survey conducted by the Center for International and Security Studies at the University of Maryland showed that:

63 percent of Russians favor eliminating all nuclear weapons, 59 percent support removing all nuclear weapons from high alert, and 53 percent support cutting the Russian and U.S. nuclear arsenals to 400 nuclear weapons each. In the United States, 73 percent of the public favors eliminating all nuclear weapons, 64 percent support removing all nuclear weapons from high alert, and 59 percent support reducing Russian and U.S. nuclear arsenals to 400 weapons each. Eighty percent of Russians and Americans want their countries to participate in the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty.[104]

Criticism of the anti-nuclear movement

Some environmentalists criticise the anti-nuclear movement for under-stating the environmental costs of fossil fuels and non-nuclear alternatives, and overstating the environmental costs of nuclear energy.[148][149]

Of the numerous nuclear experts who have offered their expertise in addressing controversies, Bernard Cohen, Professor Emeritus of Physics at the University of Pittsburgh, is likely the most frequently cited. In his extensive writings he examines the safety issues in detail. He is best known for comparing nuclear safety to the relative safety of a wide range of other phenomena.[150][151]

Anti-nuclear activists are sometimes accused of representing the risks of nuclear power in an unfair way. The War Against the Atom (Basic Books, 1982) Samuel MacCracken of Boston University argued that in 1982, 50,000 deaths per year could be attributed directly to non-nuclear power plants, if fuel production and transportation, as well as pollution, were taken into account. He argued that if non-nuclear plants were judged by the same standards as nuclear ones, each US non-nuclear power plant could be held responsible for about 100 deaths per year. [152]

The Nuclear Energy Institute[153] (NEI) is the main lobby group for companies doing nuclear work in the USA, while most countries that employ nuclear energy have a national industry group. The World Nuclear Association is the only global trade body. In seeking to counteract the arguments of nuclear opponents, it points to independent studies that quantify the costs and benefits of nuclear energy and compares them to the costs and benefits of alternatives. NEI sponsors studies of its own, but it also references studies performed for the World Health Organisation,[154] for the International Energy Agency,[155] and by university researchers.[156]

Critics of the anti-nuclear movement point to independent studies that show that the capital resources required for renewable energy sources are higher than those required for nuclear power.[155]

Some environmentalists, including former opponents of nuclear energy, criticise the movement on the basis of the claim that nuclear energy is necessary for reducing carbon dioxide emissions. These individuals include James Lovelock,[148] originator of the Gaia hypothesis, Patrick Moore[149], and Stewart Brand, creator of the Whole Earth Catalog.[157][158] Lovelock goes further to refute claims about the danger of nuclear energy and its waste products.[159] In a January 2008 interview, Moore said that "It wasn't until after I'd left Greenpeace and the climate change issue started coming to the forefront that I started rethinking energy policy in general and realised that I had been incorrect in my analysis of nuclear as being some kind of evil plot."[160]

Some anti-nuclear organisations have acknowledged that their positions are subject to review.[161] However, concern for global warming has not changed the views of many other anti-nuclear organisations toward nuclear energy:

While some environmentalists, in the interests of reducing the CO2 emissions associated with burning carbon-based fuels, have switched from anti- to pro-nuclear power in recent years, it is clear that many — if not most — of the militant environmentalist organizations remain adamantly opposed to the expansion of nuclear power. Many even propose decommissioning and dismantling the existing nuclear power electrical plants.[162]

See also

- Doomsday Clock

- Environmental movement

- John Gofman

- Gregory Minor

- List of articles about Three Mile Island

- List of Chernobyl-related articles

- List of nuclear whistleblowers

- List of states with nuclear weapons

- Leuren Moret

- Nuclear safety

- Nuclear-Free Future Award

- Uranium

References

- ^ a b Robert Benford. The Anti-nuclear Movement (book review) American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 89, No. 6, (May 1984), pp. 1456-1458.

- ^ a b c Walker, J. Samuel (2004). Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective (Berkeley: University of California Press), pp. 10-11.

- ^ Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Mary Palevsky, Robert Futrell, and Andrew Kirk. Recollections of Nevada's Nuclear Past UNLV FUSION, 2005, p. 20.

- ^ a b Jerry Brown and Rinaldo Brutoco (1997). Profiles in Power: The Anti-nuclear Movement and the Dawn of the Solar Age, Twayne Publishers, pp. 191-192.

- ^ Emsley, John (2001). "Uranium". Nature's Building Blocks: An A to Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 478. ISBN 0198503407.

- ^ a b c Wolfgang Rudig (1990). Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy, Longman, p. 54-55.

- ^ a b c Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press, pp. 96-97.

- ^ A brief history of CND

- ^ "Early defections in march to Aldermaston". Guardian Unlimited. 1958-04-05.

- ^ Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press, p. 93.

- ^ Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press, p. 98.

- ^ a b c Paula Garb. Review of Critical Masses, Journal of Political Ecology, Vol 6, 1999.

- ^ Thomas Raymond Wellock (1998). Critical Masses: Opposition to Nuclear Power in California, 1958-1978, The University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 27-28.

- ^ Keith Schneider. Larry Bogart, an Influential Critic Of Nuclear Power, Is Dead at 77 The New York Times, August 20, 1991.

- ^ Anna Gyorgy (1980). No Nukes: Everyone's Guide to Nuclear Power South End Press, ISBN 0896080064, p. 383.

- ^ a b c Wolfgang Rudig (1990). Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy, Longman, p. 52.

- ^ Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press, p. 95.

- ^ a b Dorothy Nelkin and Michael Pollak (1982). The Atom Besieged: Antinuclear Movements in France and Germany, ASIN: B0011LXE0A, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Stephen Mills and Roger Williams (1986). Public Acceptance of New Technologies Routledge, pp. 375-376.

- ^ a b Robert Gottlieb (2005). Forcing the Spring: The Transformation of the American Environmental Movement, Revised Edition, Island Press, USA, p. 237.

- ^ Nuclear Power in Germany: A Chronology

- ^ Paul Lewis. David McTaggart, a Builder of Greenpeace, Dies at 69 The New York Times, March 24, 2001.

- ^ a b c d e f Lawrence S. Wittner. Nuclear Disarmament Activism in Asia and the Pacific, 1971-1996 The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 25-5-09, June 22, 2009.

- ^ Lutz Mez, Mycle Schneider and Steve Thomas (Eds.) (2009). International Perspectives of Energy Policy and the Role of Nuclear Power, Multi-Science Publishing Co. Ltd, p. 371.

- ^ Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d e Greenpeace International and European Renewable Energy Council (January 2007). Energy Revolution: A Sustainable World Energy Outlook, p. 7. Cite error: The named reference "gierec" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Giugni, Marco (2004). Social Protest and Policy Change: Ecology, Antinuclear, and Peace Movements.

- ^ Helen Caldicott (2006). Nuclear power is not the answer to global warming or anything else, Melbourne University Press, ISBN 0 522 85251 3, p. xvii

- ^ a b c d e Brian Martin. Opposing nuclear power: past and present, Social Alternatives, Vol. 26, No. 2, Second Quarter 2007, pp. 43-47.

- ^ Terry Macalister. New generation of nuclear power stations 'risk terrorist anarchy', The Guardian, 16 March 2009.

- ^ a b c d Bill Theobald. Alexander vision for new nuclear plants faces many obstacles Jacksonsun.com, January 15, 2010.

- ^ Peter Stoett. Toward Renewed Legitimacy? Nuclear Power, Global Warming, and Security p. 110.

- ^ Jan Willem Storm van Leeuwen (2008). Nuclear power – the energy balance

- ^ Wolfgang Rudig (1990). Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy, Longman, p. 53 & p. 61.

- ^ Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press, p. 90.

- ^ Clyde W. Burleson. Nuclear Afternoon

- ^ Stephanie Cooke (2009). In Mortal Hands: A Cautionary History of the Nuclear Age, Black Inc., p. 280.

- ^ Newtan, Samuel Upton (2007). Nuclear War 1 and Other Major Nuclear Disasters of the 20th Century, AuthorHouse.

- ^ The Worst Nuclear Disasters

- ^ a b Al Gore (2009). Our Choice: A Plan to Solve the Climate Crisis, Bloomsbury, pp. 165-166.

- ^ Motevalli, Golnar (Jan 22, 2008). ""Nuclear power rebirth revives waste debate"". Reuters. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ^

""A Nuclear Power Renaissance?"". Scientific American. April 28, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^

von Hippel, Frank N. (April 2008). "Nuclear Fuel Recycling: More Trouble Than It's Worth". Scientific American. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ James Kanter. Is the Nuclear Renaissance Fizzling? Green Inc., May 29, 2009.

- ^ Mark Diesendorf (2007). Greenhouse Solutions with Sustainable Energy, University of New South Wales Press, p. 252.

- ^ a b Mark Diesendorf. Is nuclear energy a possible solution to global warming?

- ^ Nuclear power protested from Copenhagen to Washington

- ^ "Nuclear fusion reactor project in France: an expensive and senseless nuclear stupidity". Greenpeace International. 2005-06-28. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

- ^ a b Greenpeace International and European Renewable Energy Council (January 2007). Energy Revolution: A Sustainable World Energy Outlook

- ^ International Energy Agency (2007). Renewables in global energy supply: An IEA facts sheet (PDF) OECD, 34 pages.

- ^ Lester R. Brown. Plan B 4.0: Mobilizing to Save Civilization, Earth Policy Institute, 2009, p. 135.

- ^ International Energy Agency. IEA urges governments to adopt effective policies based on key design principles to accelerate the exploitation of the large potential for renewable energy 29 September 2008.

- ^ William A. Gamson and Andre Modigliani. Media Coverage and Public Opinion on Nuclear Power, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 95, No. 1, July 1989, p. 7.

- ^ Fox Butterfield. Professional Groups Flocking to Antinuclear Drive, The New York Times, March 27, 1982.

- ^ Wolfgang Rudig (1990). Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy, Longman, p. 1.

- ^ Lutz Mez, Mycle Schneider and Steve Thomas (Eds.) (2009). International Perspectives of Energy Policy and the Role of Nuclear Power, Multi-Science Publishing Co. Ltd, p. 279.

- ^ Matthew L. Wald. Nuclear Agency's Chief Praises Watchdog Groups, The New York Times, June 23, 1992.

- ^ World's best-known protest symbol turns 50, BBC News, 20 March 2008.

- ^ WISE has badges and stickers in 35 languages. WISE.

- ^ Wolfgang Rudig (1990). Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy, Longman, p. 138.

- ^ a b Yok-shiu F. Lee and Alvin Y. So (1999). Asia's Environmental Movements: Comparative Perspectives M.E. Sharpe, pp. 160-161.

- ^ West Germans Clash at Site of A-Plant New York Times, March 1, 1981 p. 17.

- ^ Nuclear Power in Germany: A Chronology

- ^ Violence Mars West German Protest New York Times, March 1, 1981 p. 17

- ^ Lawrence S. Wittner. Disarmament movement lessons from yesteryear Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 27 July 2009.

- ^ Ken Butigan (2003). Pilgrimage through a burning world: spiritual practice and nonviolent protest at the Nevada Test Site SUNY Press, chapters 2 and 3.

- ^ Blogs for Bush: The White House Of The Blogosphere: Edwards Calls Israel a Threat

- ^ Paul Brown, Shyama Perera and Martin Wainwright. Protest by CND stretches 14 miles The Guardian, 2 April 1983.

- ^ John Greenwald. Energy and Now, the Political Fallout, TIME, June 2, 1986.

- ^ Marco Giugni (2004). Social protest and policy change p. 55.

- ^ Hundreds of Marchers Hit Washington in Finale of Nationwide Peace March Gainsville Sun, November 16, 1986.

- ^ "Semipalatinsk: 60 years later (collection of articles)". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. September 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher=|publisher=(help) - ^ World: Asia-Pacific: Kazakh anti-nuclear movement celebrates tenth anniversary BBC News, February 28, 1999.

- ^ Matthew Chance. Inside the nuclear underworld: Deformity and fear CNN.com, August 31, 2007.

- ^ Protests Stop Devastating Nuclear Tests: The Nevada-Semipalatinsk Anti-Nuclear Movement in Kazakhstan

- ^ ZNet |Activism | The Power of Protest

- ^ Interest Group Politics In America p. 149.

- ^ a b Social Protest and Policy Change p. 45.

- ^ Herman, Robin (September 24, 1979). "Nearly 200,000 Rally to Protest Nuclear Energy". New York Times. p. B1.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Michael Kenney. Tracking the protest movements that had roots in New England The Boston Globe, December 30, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Williams, Eesha. Wikipedia distorts nuclear history Rutland Herald, May 1, 2008.

- ^ William A. Gamson and Andre Modigliani. Media Coverage and Public Opinion on Nuclear Power, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 95, No. 1, July 1989, p. 17.

- ^ Social Protest and Policy Change p. 44.

- ^ a b Amplifying Public Opinion: The Policy Impact of the U.S. Environmental Movement p. 7.

- ^ Nonviolent Social Movements p. 295.

- ^ Headline: Rocky Flats Nuclear Plant / Protest

- ^ Anti-Nuclear Demonstrations

- ^ Shoreham Action Is One of Largest Held Worldwide; 15,000 Protest L.I. Atom Plant; 600 Seized 600 Arrested on L.I. as 15,000 Protest at Nuclear Plant Nuclear Supporter on Hand Governor Stresses Safety Thousands Protest Worldwide New York Times, June 4, 1979.

- ^ Gottlieb, Robert (2005). Forcing the Spring: The Transformation of the American Environmental Movement, Revised Edition, Island Press, USA, p. 240.

- ^ Discourse analysis by Brian Paltridge p. 188.

- ^ Lance Murdoch. Pictures: New York MayDay anti-nuke/war march IndyMedia, 2 may 2005.

- ^ Anti-Nuke Protests in New York Fox News, May 2, 2005.

- ^ Williams, Estha. Nuke Fight Nears Decisive Moment Valley Advocate, August 28, 2008.

- ^ Newtan, Samuel Upton (2007). Nuclear War 1 and Other Major Nuclear Disasters of the 20th Century, AuthorHouse, p. 96.

- ^ WISE Paris. The threat of nuclear terrorism:from analysis to precautionary measures. 10 December 2001.

- ^ Indymedia UK. Activist Killed in Anti-nuke Protest.

- ^ Energy Daily. Russian Anti-Nuclear Activist Killed In Attack. July 21, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Research and Markets: International Perspectives on Energy Policy and the Role of Nuclear Power Reuters, May 6, 2009.

- ^ a b Roy McLeod (1995). "Resistance to Nuclear Technology: Optimists, Opportunists and Opposition in Australian Nuclear History" in Martin Bauer (ed) Resistance to New Technology, Cambridge University Press, pp. 175-177.

- ^ Thousands march in Paris anti-nuclear protest ABC News, January 18, 2004.

- ^ Lance Murdoch. Pictures: New York MayDay anti-nuke/war march IndyMedia, 2 may 2005.

- ^ Anti-Nuke Protests in New York Fox News, May 2, 2005.

- ^ a b c d Lawrence S. Wittner. A rebirth of the anti-nuclear weapons movement? Portents of an anti-nuclear upsurge Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 7 December 2007.

- ^ "French protests over EPR". Nuclear Engineering International. 2007-04-03.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "France hit by anti-nuclear protests". Evening Echo. 2007-04-03.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ The Renaissance of the Anti-Nuclear Movement Spiegel Online, 11/10/2008.

- ^ Anti-Nuclear Protest Reawakens: Nuclear Waste Reaches German Storage Site Amid Fierce Protests Spiegel Online, 11/11/2008.

- ^ Simon Sturdee. Police break up German nuclear protest The Age, November 11, 2008.

- ^ Green boost in European elections may trigger nuclear fight, Nature, 9 June 2009.

- ^ More than 30 arrests at Aldermaston anti-nuclear protest The Guardian, 28 October 2008.

- ^ Protest against nuclear reactor Chicago Tribune, October 16, 2008.

- ^ Southeast Climate Convergence occupies nuclear facility Indymedia UK, August 8, 2008.

- ^ Anti-Nuclear Renaissance: A Powerful but Partial and Tentative Victory Over Atomic Energy

- ^ Maryann Spoto. [http://www.nj.com/news/ledger/jersey/index.ssf?/base/news-14/1243915641194930.xml&coll=1 Nuclear license renewal sparks protest Star-Ledger, June 02, 2009.

- ^ Anti-nuclear protesters reach capitol Rutland Herald, January 14, 2010.

- ^ Eric Kirschbaum. Anti-nuclear rally enlivens German campaign Reuters, September 5, 2009.

- ^ 50,000 join anti-nuclear power march in Berlin The Local, September 5, 2009.

- ^ Roger Boyes. German nuclear programme threatened by old mine housing waste The Times, January 22, 2010.

- ^ Bosley Crowther. Movie Review: Dr. Strangelove (1964) The New York Times, January 31, 1964.

- ^ The China Syndrome (1979) The New York Times.

- ^ Herman, Robin (September 24, 1979). "Nearly 200,000 Rally to Protest Nuclear Energy". New York Times. p. B1.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ “For What It’s Worth,” No Nukes Reunite After Thirty Years

- ^ Musicians Act to Stop New Atomic Reactors

- ^ Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Confronting the Bomb: A Short History of the World Nuclear Disarmament Movement

- ^ Jim Doyle. Nuclear power industry sees opening for revival San Francisco Chronicle, March 9, 2009.

- ^ Minnesota House says no to new nuclear power plants StarTribune.com, April 30, 2009.

- ^ Rebecca A. McNerney (1998). The Changing Structure of the Electric Power Industry p. 110.

- ^ a b William A. Gamson and Andre Modigliani. Media Coverage and Public Opinion on Nuclear Power, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 95, No. 1, July 1989, p. 15.

- ^ New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act

- ^ "Nuclear Energy Prospects in New Zealand". World Nuclear Association. 2009-04. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Nuclear power backed by 19%.

- ^ Italy

- ^ Italy joins GNEP

- ^ a b The Radioactive Energy Plan

- ^ German Parties Set to Clash Over Nuclear Power

- ^ Electricity Regulation Act, 1999

- ^ Navajo Nation outlaws uranium mining

- ^ Support for N-power falls The Australian, 30 December 2006.

- ^ Mycle Schneider, Steve Thomas, Antony Froggatt, Doug Koplow (August 2009). The World Nuclear Industry Status Report, German Federal Ministry of Environment, Nature Conservation and Reactor Safety, p. 6.

- ^ Ralph Summy. Confronting the Bomb (book review), Social Alternatives, Vol. 28, No. 3, 2009, p. 64.

- ^ a b c International Atomic Energy Agency (2005). Global Public Opinion on Nuclear Issues and the IAEA: Final Report from 18 Countries p. 6.

- ^ Survey Reveals Gap in Public’s Awareness

- ^ Energy

- ^ Stephen Ansolabehere. Public Attitudes Toward America’s Energy Options Report of the 2007 MIT Energy Survey, Center for Energy and Environmental Policy research, March 2007, p. 3.

- ^ EurActiv.com - Majority of Europeans oppose nuclear power | EU - European Information on EU Priorities & Opinion

- ^ http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_271_en.pdf

- ^ a b James Lovelock: Nuclear power is the only green solution

- ^ a b Going Nuclear

- ^ Bernard Cohen

- ^ The Nuclear Energy Option

- ^ Samuel MacCracken, The War Against the Atom, 1982, Basic Books, pp. 60-61

- ^ Nuclear Energy Institute website

- ^ Fourth Ministerial Conference on Environment and Health: Budapest, Hungary, 23–25 June 2004

- ^ a b Executive Summary

- ^ Ari Rabl and Mona. Dreicer, Health and Environmental Impacts of Energy Systems. International Journal of Global Energy Issues, vol.18(2/3/4), 113-150 (2002)

- ^ Environmental Heresies

- ^ An Early Environmentalist, Embracing New ‘Heresies’

- ^ James Lovelock

- ^ [1]

- ^ Some rethinking nuke opposition USA Today

- ^ William F. Jasper. NGO Demonstrators: No to Coal, No to Oil, No to Nuclear New American, 16 December 2009.

Bibliography

- Brown, Jerry and Rinaldo Brutoco (1997). Profiles in Power: The Anti-nuclear Movement and the Dawn of the Solar Age, Twayne Publishers.

- Clarfield, Gerald H. and William M. Wiecek (1984). Nuclear America: Military and Civilian Nuclear Power in the United States 1940-1980, Harper & Row.

- Cooke, Stephanie (2009). In Mortal Hands: A Cautionary History of the Nuclear Age, Black Inc.

- Cragin, Susan (2007). Nuclear Nebraska: The Remarkable Story of the Little County That Couldn’t Be Bought, AMACOM.

- Dickerson, Carrie B. and Patricia Lemon (1995). Black Fox: Aunt Carrie's War Against the Black Fox Nuclear Power Plant, Council Oak Publishing Company, ISBN 1571780092

- Diesendorf, Mark (2009). Climate Action: A Campaign Manual for Greenhouse Solutions, University of New South Wales Press.

- Diesendorf, Mark (2007). Greenhouse Solutions with Sustainable Energy, University of New South Wales Press.

- Elliott, David (2007). Nuclear or Not? Does Nuclear Power Have a Place in a Sustainable Energy Future?, Palgrave.

- Falk, Jim (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press.

- Fradkin, Philip L. (2004). Fallout: An American Nuclear Tragedy, University of Arizona Press.

- Giugni, Marco (2004). Social Protest and Policy Change: Ecology, Antinuclear, and Peace Movements in Comparative Perspective, Rowman and Littlefield.

- Jasper, James M. (1997). The Art of Moral Protest: Culture, Biography, and Creativity in Social Movements, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0226394816

- Lovins, Amory B. (1977). Soft Energy Paths: Towards a Durable Peace, Friends of the Earth International, ISBN 0-06-090653-7

- Lovins, Amory (2008). The Nuclear Illusion, Rocky Mountain Institute.

- Lovins, Amory B. and John H. Price (1975). Non-Nuclear Futures: The Case for an Ethical Energy Strategy, Ballinger Publishing Company, 1975, ISBN 0884106020

- Lowe, Ian (2007). Reaction Time: Climate Change and the Nuclear Option, Quarterly Essay.

- McCafferty, David P. (1991). The Politics of Nuclear Power: A History of the Shoreham Power Plant, Kluwer.

- Natti, Susanna and Bonnie Acker (1979). No Nukes: Everyone's Guide to Nuclear Power, South End Press.

- Newtan, Samuel Upton (2007). Nuclear War 1 and Other Major Nuclear Disasters of the 20th Century, AuthorHouse.

- Ondaatje, Elizabeth H. (c1988). Trends in Antinuclear Protests in the United States, 1984-1987, Rand Corporation.

- Parkinson, Alan (2007). Maralinga: Australia’s Nuclear Waste Cover-up, ABC Books.

- Pernick, Ron and Clint Wilder (2007). The Clean Tech Revolution: The Next Big Growth and Investment Opportunity, Collins, ISBN 978-0060896232

- Peterson, Christian (2003). Ronald Reagan and Antinuclear Movements in the United States and Western Europe, 1981-1987, Edwin Mellen Press.

- Polletta, Francesca (2002). Freedom Is an Endless Meeting: Democracy in American Social Movements, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0226674495

- Price, Jerome (1982). The Antinuclear Movement, Twayne Publishers.

- Rudig, Wolfgang (1990). Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy, Longman.

- Schneider, Mycle, Steve Thomas, Antony Froggatt, Doug Koplow (August 2009). The World Nuclear Industry Status Report, German Federal Ministry of Environment, Nature Conservation and Reactor Safety.

- Smith, Jennifer (Editor), (2002). The Antinuclear Movement, Cengage Gale.

- Surbrug, Robert (2009). Beyond Vietnam: The Politics of Protest in Massachusetts, 1974-1990, University of Massachusetts Press.

- Walker, J. Samuel (2004). Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective, University of California Press.

- Wellock, Thomas R. (1998). Critical Masses: Opposition to Nuclear Power in California, 1958-1978, The University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 0299158500

- Wills, John (2006). Conservation Fallout: Nuclear Protest at Diablo Canyon, University of Nevada Press.

- Wittner, Lawrence S. (2009). Confronting the Bomb: A Short History of the World Nuclear Disarmament Movement, Stanford University Press.

![The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament symbol, designed in 1958. It later became a universal peace symbol used in many different versions worldwide.[59]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4f/Peace_symbol.svg/120px-Peace_symbol.svg.png)