XYZ Affair: Difference between revisions

add requested cites |

add cites on French |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

The '''XYZ Affair''' is a diplomatic episode that soured relations between [[France]] and the [[United States]]; it took place from March of [[1797]] to [[1800]].<ref> Miller, (1960), pp 210-227</ref> |

The '''XYZ Affair''' is a diplomatic episode that soured relations between [[France]] and the [[United States]]; it took place from March of [[1797]] to [[1800]].<ref> Miller, (1960), pp 210-227</ref> |

||

Three French agents, publicly referred to as X, Y, and Z, but later revealed as [[Baron Jean-Conrad Hottinguer|Jean Conrad Hottinguer]], Pierre Bellamy and Lucien Hauteval, demanded major concessions from the United States as a condition for continuing bilateral peace [[negotiation]]s. The concessions demanded by the French included 50,000 [[pounds sterling]], a $12 million loan from the [[United States]], a $250,000 personal bribe to [[Minister of Foreign Affairs (France)|French foreign minister]] [[Charles Maurice de Talleyrand]], and a formal apology for comments made by [[President of the United States|U.S. President]] [[John Adams]].<ref> T. M. Iiams, ''Peacemaking from Vergennes to Napoleon: French Foreign Relations in the Revolutionary Era, 1774-1814'' (1979)</ref> |

Three French agents, publicly referred to as X, Y, and Z, but later revealed as [[Baron Jean-Conrad Hottinguer|Jean Conrad Hottinguer]], Pierre Bellamy and Lucien Hauteval, demanded major concessions from the United States as a condition for continuing bilateral peace [[negotiation]]s. The concessions demanded by the French included 50,000 [[pounds sterling]], a $12 million loan from the [[United States]], a $250,000 personal bribe to [[Minister of Foreign Affairs (France)|French foreign minister]] [[Charles Maurice de Talleyrand]], and a formal apology for comments made by [[President of the United States|U.S. President]] [[John Adams]].<ref> T. M. Iiams, ''Peacemaking from Vergennes to Napoleon: French Foreign Relations in the Revolutionary Era, 1774-1814'' (1979); A. Duff Cooper, ''Talleyrand'' (1932); E. Wilson Lyon, "The Directory and the United States," ''American Historical Review,'' Vol. 43, No. 3 (Apr., 1938), pp. 514-532 [http://www.jstor.org/stable/1865613 in JSTOR]</ref> |

||

The demand came during a meeting in |

The demand came during a meeting in Paris between the French agents and a three member American commission consisting of [[Charles Cotesworth Pinckney]], [[John Marshall]], and [[Elbridge Gerry]]. Several weeks prior to the meeting with X, Y, and Z, the American commission had met with French foreign minister Talleyrand to discuss French retaliation to the [[Jay Treaty]], which they perceived as evidence of an [[Anglo-American relations|Anglo-American]] alliance. The French seized nearly 300 American ships bound for British ports in the Atlantic, Mediterranean, and Caribbean seas.<ref> Stinchcombe (1980)</ref> |

||

Adams decided on sending Pinckney as part of the commission as [[Franco-U.S. relations]] had recently worsened by [[Talleyrand]]'s rejection of Pinckney as America's minister to France. The French continued to seize American ships, and the [[Federalist Party (United States)| |

Adams decided on sending Pinckney as part of the commission as [[Franco-U.S. relations]] had recently worsened by [[Talleyrand]]'s rejection of Pinckney as America's minister to France. The French continued to seize American ships, and the [[Federalist Party (United States)|Federalist Party]], incited by [[Alexander Hamilton]] advocated going to war. Congress authorized the buildup of an army<ref>Elkins and McKitrick, (1993) pp 665-9</ref> |

||

The American delegates found these demands unacceptable and answered "Not a sixpence", but in the inflated rhetoric of the day the response became the infinitely more memorable: "Millions for defense, sir, but not one cent for tribute!" |

The American delegates found these demands unacceptable and answered "Not a sixpence", but in the inflated rhetoric of the day the response became the infinitely more memorable: "Millions for defense, sir, but not one cent for tribute!"<ref> Stinchcombe (1980)</ref> |

||

The U.S. offered France many of the same provisions found in the [[Jay Treaty]] with Britain, but France reacted by deporting Marshall and Pinckney back to the United States, refusing any proposal that would involve these two delegates. Gerry remained in France, thinking he could prevent a declaration of war, but did not officially negotiate any further.<ref> Smith (1986)</ref> |

The U.S. offered France many of the same provisions found in the [[Jay Treaty]] with Britain, but France reacted by deporting Marshall and Pinckney back to the United States, refusing any proposal that would involve these two delegates. Gerry remained in France, thinking he could prevent a declaration of war, but did not officially negotiate any further.<ref> Smith (1986)</ref> |

||

Revision as of 08:53, 31 December 2009

The XYZ Affair is a diplomatic episode that soured relations between France and the United States; it took place from March of 1797 to 1800.[1]

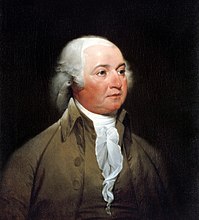

Three French agents, publicly referred to as X, Y, and Z, but later revealed as Jean Conrad Hottinguer, Pierre Bellamy and Lucien Hauteval, demanded major concessions from the United States as a condition for continuing bilateral peace negotiations. The concessions demanded by the French included 50,000 pounds sterling, a $12 million loan from the United States, a $250,000 personal bribe to French foreign minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand, and a formal apology for comments made by U.S. President John Adams.[2]

The demand came during a meeting in Paris between the French agents and a three member American commission consisting of Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, John Marshall, and Elbridge Gerry. Several weeks prior to the meeting with X, Y, and Z, the American commission had met with French foreign minister Talleyrand to discuss French retaliation to the Jay Treaty, which they perceived as evidence of an Anglo-American alliance. The French seized nearly 300 American ships bound for British ports in the Atlantic, Mediterranean, and Caribbean seas.[3]

Adams decided on sending Pinckney as part of the commission as Franco-U.S. relations had recently worsened by Talleyrand's rejection of Pinckney as America's minister to France. The French continued to seize American ships, and the Federalist Party, incited by Alexander Hamilton advocated going to war. Congress authorized the buildup of an army[4]

The American delegates found these demands unacceptable and answered "Not a sixpence", but in the inflated rhetoric of the day the response became the infinitely more memorable: "Millions for defense, sir, but not one cent for tribute!"[5]

The U.S. offered France many of the same provisions found in the Jay Treaty with Britain, but France reacted by deporting Marshall and Pinckney back to the United States, refusing any proposal that would involve these two delegates. Gerry remained in France, thinking he could prevent a declaration of war, but did not officially negotiate any further.[6]

President Adams released the report of the affair resulting in a wave of passionate anti-French sentiment across the U.S.[7] A formal declaration of war was narrowly, and only temporarily, avoided by Adams' diplomacy; specifically by appointing new diplomats including William Murray to handle the growing conflict.

Regardless of the lack of a formal declaration of war, continued French raids against American merchantmen led to the abrogation of the Franco-American Alliance in the Quasi-War (July 7, 1798-1800). Adams again sent negotiators on January 18, 1799, which eventually negotiated an end to hostilities through the Treaty of Mortefontaine. During negotiations with France, the U.S. began to build up its navy, a move long supported by Adams and Marshall, to defend against both the French and the British. In addition, in a speech delivered on July 16, 1797, Adams championed the formulation of a navy and army while emphasizing the importance of renewing treaties with Prussia and Sweden.[8]

References

- ^ Miller, (1960), pp 210-227

- ^ T. M. Iiams, Peacemaking from Vergennes to Napoleon: French Foreign Relations in the Revolutionary Era, 1774-1814 (1979); A. Duff Cooper, Talleyrand (1932); E. Wilson Lyon, "The Directory and the United States," American Historical Review, Vol. 43, No. 3 (Apr., 1938), pp. 514-532 in JSTOR

- ^ Stinchcombe (1980)

- ^ Elkins and McKitrick, (1993) pp 665-9

- ^ Stinchcombe (1980)

- ^ Smith (1986)

- ^ Ray (1983)

- ^ Ferling (1992)

Further reading

- Brown, Ralph A. The Presidency of John Adams. (1988).

- Elkins, Stanley M. and Eric McKitrick, The Age of Federalism. (1993)

- Ferling, John. John Adams: A Life. (1992)

- Hale, Matthew Rainbow. "'Many Who Wandered in Darkness': the Contest over American National Identity, 1795-1798." Early American Studies 2003 1(1): 127-175. Issn: 1543-4273

- Miller, John C. The Federalist Era: 1789-1801 (1960), pp 210-227

- Ray, Thomas M. "'Not One Cent for Tribute': The Public Addresses and American Popular Reaction to the XYZ Affair, 1798-1799." Journal of the Early Republic (1983) 3(4): 389-412. in Jstor

- Jean Edward Smith, John Marshall: Definer Of A Nation, New York: Henry, Holt & Company, 1996.

- Stinchcombe, William. The XYZ Affair. Greenwood, 1980. 167 pp.

- Stinchcombe, William. "The Diplomacy of the WXYZ Affair," in William and Mary Quarterly, 34:590-617 (October 1977); in JSTOR; note the "W".