Vivre sa vie: Difference between revisions

Moving deprecated amg_id and imdb_id from {{Infobox Film}} to External links per request |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

''Vivre sa vie'' was released shortly after ''[[Cahiers du cinéma]]'' (the film magazine for which Godard occasionally wrote) published an issue devoted to [[Bertolt Brecht]] and his theory of '[[epic theatre]]'. Godard may have been influenced by it, as ''Vivre sa vie'' uses several [[Distancing effect|alienation effects]]: twelve [[intertitle]]s appear before the film's 'chapters' explaining what will happen next; [[jump cut]]s disrupt the editing flow; characters are shot from behind when they are talking; they are strongly backlit; they talk directly to the camera; the statistical results derived from official questionnaires are given in a [[voice-over]]; and so on. |

''Vivre sa vie'' was released shortly after ''[[Cahiers du cinéma]]'' (the film magazine for which Godard occasionally wrote) published an issue devoted to [[Bertolt Brecht]] and his theory of '[[epic theatre]]'. Godard may have been influenced by it, as ''Vivre sa vie'' uses several [[Distancing effect|alienation effects]]: twelve [[intertitle]]s appear before the film's 'chapters' explaining what will happen next; [[jump cut]]s disrupt the editing flow; characters are shot from behind when they are talking; they are strongly backlit; they talk directly to the camera; the statistical results derived from official questionnaires are given in a [[voice-over]]; and so on. |

||

The film also draws from the writings of [[Montaigne]], [[Baudelaire]], [[Émile Zola|Zola]] and [[Edgar Allan Poe]], to the cinema of [[Robert Bresson]], [[Jean Renoir]] and [[Carl Dreyer]].{{Fact|date=April 2008}} Nana gets into an earnest discussion with a philosopher (played by [[Brice Parain]], Godard's former philosophy tutor), about the limits of speech and written language. In the next scene, as if to illustrate this point, the sound track ceases and the images are overlaid by Godard's personal narration. This formal playfulness is typical of the way in which the director was working with sound and vision during this period.{{Fact|date=April 2008}} |

The film also draws from the writings of [[Montaigne]], [[Baudelaire]], [[Émile Zola|Zola]] and [[Edgar Allan Poe]], to the cinema of [[Robert Bresson]], [[Jean Renoir]] and [[Carl Dreyer]].{{Fact|date=April 2008}} And Jean Douchet, the French critic, has written that Godard's film ' would have been impossible without [[Street of Shame]], [[Kenji Mizoguchi]]'s last and most sublime film.' <ref> Jean Douchet ' French New Wave' ISBN 1-56466-057-5 </ref> Nana gets into an earnest discussion with a philosopher (played by [[Brice Parain]], Godard's former philosophy tutor), about the limits of speech and written language. In the next scene, as if to illustrate this point, the sound track ceases and the images are overlaid by Godard's personal narration. This formal playfulness is typical of the way in which the director was working with sound and vision during this period.{{Fact|date=April 2008}} |

||

[[Image:Vivre1-filmog.jpg|thumb|300px|left|[[Anna Karina]] and [[Sady Rebbot]] in ''Vivre sa vie'']] |

[[Image:Vivre1-filmog.jpg|thumb|300px|left|[[Anna Karina]] and [[Sady Rebbot]] in ''Vivre sa vie'']] |

||

Revision as of 12:46, 28 April 2009

| Vivre sa vie | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Jean-Luc Godard |

| Written by | Jean-Luc Godard Marcel Sacotte |

| Produced by | Pierre Braunberger |

| Starring | Anna Karina Sady Rebbot André S. Labarthe Guylaine Schlumberger Gérard Hoffman |

| Edited by | Jean-Luc Godard Agnès Guillemot |

| Distributed by | Panthéon Distribution |

Release date | 1962 |

Running time | 85 min. |

| Language | French |

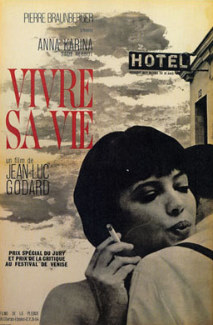

Vivre sa Vie: Film en Douze Tableaux ("To Live Her Life: A Film in Twelve Scenes") is a 1962 film directed by Jean-Luc Godard. It was released in the U.S. as My Life to Live and in the UK as It's My Life.

The film stars Anna Karina, Godard's then wife, as Nana, a young Parisian woman who abandons her marriage and a child in order to pursue a career as an actress. Faced with financial troubles she drifts into prostitution. Nana believes she makes this choice of her own free will, but the film emphasizes the social structure that forces the poor into such situations, and builds to a tragic conclusion.

Style

In Vivre sa vie, Godard borrowed the aesthetics of the cinéma vérité approach to documentary film-making that was then becoming fashionable. However, this film differed from other films of the French New Wave by being photographed with a heavy Mitchell camera, as opposed to the light weight cameras used for earlier films.[citation needed] The cinematographer was Raoul Coutard, a frequent collaborator of Godard.

Influences

This section possibly contains original research. (April 2008) |

One of the film's original sources is a study of contemporary prostitution, Où en est la prostitution by Marcel Sacotte, an examining magistrate.

Vivre sa vie was released shortly after Cahiers du cinéma (the film magazine for which Godard occasionally wrote) published an issue devoted to Bertolt Brecht and his theory of 'epic theatre'. Godard may have been influenced by it, as Vivre sa vie uses several alienation effects: twelve intertitles appear before the film's 'chapters' explaining what will happen next; jump cuts disrupt the editing flow; characters are shot from behind when they are talking; they are strongly backlit; they talk directly to the camera; the statistical results derived from official questionnaires are given in a voice-over; and so on.

The film also draws from the writings of Montaigne, Baudelaire, Zola and Edgar Allan Poe, to the cinema of Robert Bresson, Jean Renoir and Carl Dreyer.[citation needed] And Jean Douchet, the French critic, has written that Godard's film ' would have been impossible without Street of Shame, Kenji Mizoguchi's last and most sublime film.' [1] Nana gets into an earnest discussion with a philosopher (played by Brice Parain, Godard's former philosophy tutor), about the limits of speech and written language. In the next scene, as if to illustrate this point, the sound track ceases and the images are overlaid by Godard's personal narration. This formal playfulness is typical of the way in which the director was working with sound and vision during this period.[citation needed]

The film depicts the consumerist culture of Godard's Paris; a shiny new world of cinemas, coffee bars, neon-lit pool halls, pop records, photographs, wall posters, pin-ups, pinball machines, juke boxes, foreign cars, the latest hairstyles, typewriters, advertising, gangsters and Americana. It also features allusions to popular culture; for example, the scene where a melancholy young man walks into a cafe, puts on a juke box disc, and then sits down to listen. The unnamed actor is in fact the well known singer-songwriter Jean Ferrat, who is performing his own hit tune "Ma Môme" on the track that he has just selected. Nana's bobbed haircut replicates that made famous by Louise Brooks in the 1928 film Pandora's Box, where the doomed heroine also falls into a life of prostitution and violent death. In one sequence we are shown a queue outside a Paris cinema waiting to see Jules et Jim, the new wave film directed by François Truffaut, at the time both a close friend and sometime rival of Godard.

Responses

Susan Sontag, author and cultural critic, has described Godard's achievement in Vivre sa Vie as "a perfect film" and "one of the most extraordinary, beautiful, and original works of art that I know of."[2]

The twelve tableaux

The divisions of this film are displayed as intertitles on the screen. These are:

- Tableau one: A bistro - Nana wants to leave Paul - Pinball

- Tableau two: The record shop - 2000 francs - Nana lives her life

- Tableau three: The concierge - The passion of Joan of Arc - a journalist

- Tableau four: The police - Nana is questioned

- Tableau five: The outer boulevards - the first man - the hotel room

- Tableau six: Yvette - a café in the suburbs - Raoul - machine gun fire

- Tableau seven: The letter - Raoul again - the Champs Élysées

- Tableau eight: Afternoons - money - wash-basins - pleasure - hotels

- Tableau nine: A young man - Nana wonders if she's happy

- Tableau ten: The sidewalk - a man - there's no gaiety in happiness

- Tableau eleven: Place de Chatelet - the stranger - Nana the unwitting philosopher

- Tableau twelve: The young man again - the oval portrait - Raoul sells Nana

References

Further reading

- Colin MacCabe (2004) Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at Seventy, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 0-374-16378-2.