Morphine: Difference between revisions

Thegoodson (talk | contribs) |

Thegoodson (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 205: | Line 205: | ||

The withdrawal symptoms associated with morphine addiction are usually experienced shortly before the time of the next scheduled dose, sometimes within as early as a few hours (usually between 6-12 hours) after the last administration. Early symptoms include strong drug craving, watery eyes, insomnia, diarrhea, runny nose, yawning, dysphoria, and sweating. Restlessness, irritability, loss of appetite, body aches, severe abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, tremors, and even stronger and more intense drug craving appear as the syndrome progresses. Severe depression and vomiting are very common. The heart rate and blood pressure are elevated. Chills or cold flashes with goose bumps ("cold turkey") alternating with flushing (hot flashes), kicking movements of the legs ("kicking the habit") and excessive sweating are also characteristic symptoms.<ref>http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/People/injury/research/job185drugs/morphine.htm</ref> Severe pains in the bones and muscles of the back and extremities occur, as do muscle spasms. At any point during this process, a suitable narcotic can be administered that will dramatically reverse the withdrawal symptoms. Major withdrawal symptoms peak between 48 and 96 hours after the last dose and subside after about 8 to 12 days. Sudden withdrawal by heavily dependent users who are in poor health is occasionally fatal, although morphine withdrawal is considered less dangerous than alcohol or barbiturate withdrawal.<ref>http://www.usdoj.gov/dea/concern/narcotics.html</ref> |

The withdrawal symptoms associated with morphine addiction are usually experienced shortly before the time of the next scheduled dose, sometimes within as early as a few hours (usually between 6-12 hours) after the last administration. Early symptoms include strong drug craving, watery eyes, insomnia, diarrhea, runny nose, yawning, dysphoria, and sweating. Restlessness, irritability, loss of appetite, body aches, severe abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, tremors, and even stronger and more intense drug craving appear as the syndrome progresses. Severe depression and vomiting are very common. The heart rate and blood pressure are elevated. Chills or cold flashes with goose bumps ("cold turkey") alternating with flushing (hot flashes), kicking movements of the legs ("kicking the habit") and excessive sweating are also characteristic symptoms.<ref>http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/People/injury/research/job185drugs/morphine.htm</ref> Severe pains in the bones and muscles of the back and extremities occur, as do muscle spasms. At any point during this process, a suitable narcotic can be administered that will dramatically reverse the withdrawal symptoms. Major withdrawal symptoms peak between 48 and 96 hours after the last dose and subside after about 8 to 12 days. Sudden withdrawal by heavily dependent users who are in poor health is occasionally fatal, although morphine withdrawal is considered less dangerous than alcohol or barbiturate withdrawal.<ref>http://www.usdoj.gov/dea/concern/narcotics.html</ref> |

||

The psychological dependence associated with morphine [[addiction]] is complex and protracted. Long after the physical need for morphine has passed, the addict will usually continue to think and talk about the use of morphine (or other drugs) and feel strange or overwhelmed coping with daily activities without being under the influence of morphine. Psychological withdrawal from morphine is a very long and painful process. Addicts often suffer severe depression, anxiety, insomnia, mood swings, amnesia (forgetfulness), low self-esteem, confusion, paranoia, and other psychological disorders. The psychological dependence on morphine can, and usually does last a lifetime.<ref>O'Neal, Maryadele J. Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals. Merck. October 18, 2006.</ref> There is a high probability that relapse will occur after morphine withdrawal when neither the physical environment nor the behavioral motivators that contributed to the abuse have been altered. Testimony to morphine's addictive and reinforcing nature is its relapse rate. Abusers of morphine (and heroin), have the highest relapse rates among all drug users, including abusers of other [[opioids]], [[cocaine]], and [[methamphetamine]].[http://www.usdoj.gov/dea/concern/narcotics.html] |

The psychological dependence associated with morphine [[addiction]] is complex and protracted. Long after the physical need for morphine has passed, the addict will usually continue to think and talk about the use of morphine (or other drugs) and feel strange or overwhelmed coping with daily activities without being under the influence of morphine. Psychological withdrawal from morphine is a very long and painful process.<ref>http://opioids.com/morphine/depression.html</ref> Addicts often suffer severe depression, anxiety, insomnia, mood swings, amnesia (forgetfulness), low self-esteem, confusion, paranoia, and other psychological disorders. The psychological dependence on morphine can, and usually does last a lifetime.<ref>O'Neal, Maryadele J. Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals. Merck. October 18, 2006.</ref> There is a high probability that relapse will occur after morphine withdrawal when neither the physical environment nor the behavioral motivators that contributed to the abuse have been altered. Testimony to morphine's addictive and reinforcing nature is its relapse rate. Abusers of morphine (and heroin), have the highest relapse rates among all drug users, including abusers of other [[opioids]], [[cocaine]], and [[methamphetamine]].[http://www.usdoj.gov/dea/concern/narcotics.html] Other complications that may arise from long term morphine abuse, that is not seen with other narcotic analgesics, is neurotoxicity and brain damage. It is not fully understood yet exactly how morphine may cause neurotoxicity, but a metabolite of morphine may be responsible.<ref>Alterations in Blood-Brain Barrier Function by Morphine and Methamphetamine: H. S. Sharma, and S. F. Ali</ref> |

||

===Hepatitis C and morphine withdrawal=== |

===Hepatitis C and morphine withdrawal=== |

||

Revision as of 01:40, 24 July 2007

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Extremely High |

| Routes of administration | smoked/inhaled, insufflated, Oral, SC, IM, IV |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~15% |

| Protein binding | 30–40% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic 90% |

| Elimination half-life | 2–3 hours |

| Excretion | Renal 90%, biliary 10% |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.291 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H19NO3 |

| Molar mass | 285.4 g·mol−1 |

Indicated for:

Recreational uses: Other uses: |

Contraindications:

|

| Side effects:

Atypical sensations:

Eye:

Skin:

|

Morphine (INN) (IPA: [ˈmɔ(ɹ)fin]) is a highly potent opiate analgesic drug and is the principal active agent in opium and the prototypical opiate. Like other opiates, e.g. diacetylmorphine (heroin), morphine acts directly on the central nervous system (CNS) to relieve pain, and at synapses of the nucleus accumbens in particular. Studies done on the efficacy of various opioids have indicated that, in the management of severe pain, no other narcotic analgesic is more effective or superior to morphine. Morphine is highly addictive when compared to other substances, and tolerance and physical and psychological dependences develop very rapidly.

Patients on morphine sometimes report insomnia, visual hallucinations and nightmares;[1] if these occur then reduction in dosage or switch to an alternative opioid analgesic should be considered.

The word "morphine" is derived from Morpheus, the god of dreams in Greek mythology. He is the son of Hypnos, god of sleep.

Medical uses

Morphine is used legally:

- as an analgesic in hospital settings to relieve

- pain in myocardial Infarction

- pain after surgery

- pain associated with trauma

- in the relief of severe chronic pain, e.g.

- cancer pain

- pain from kidney stones

- severe back pain

- as an adjunct to general anesthesia

- in epidural anesthesia or intrathecal analgesia

- for palliative care (i.e. to alleviate pain without curing the underlying reason for it, usually because the latter is found impossible)

- as an antitussive for severe cough

- in nebulised form, for treatment of dyspnea, although the evidence for efficacy is slim[1]. Evidence is better for other routes [2].

- as an antidiarrheal in chronic conditions (e.g., for diarrhea associated with AIDS), although loperamide (a non-absorbed opioid acting only on the gut) is the most commonly used opioid for diarrhea.

Contraindications

- acute respiratory depression

- acute pancreatitis (this may be a result of morphine use as well) because morphine may cause spasm of the sphincter of Oddi and worsen the pain

- renal failure (due to accumulation of the metabolite morphine-6-glucuronide)

- chemical toxicity (potentially lethal in low tolerance subjects)

- raised intracranial pressure, including head injury (exacerbation due pCO2 increases from respiratory depression)

Pharmacology

Morphine is the prototype narcotic drug and is the gold standard against which all other opioids are tested. It interacts predominantly with the µ-opioid receptor. These µ-binding sites are discretely distributed in the human brain, with high densities in the posterior amygdala, hypothalamus, thalamus, nucleus caudatus, putamen, and certain cortical areas. They are also found on the terminal axons of primary afferents within laminae I and II (substantia gelatinosa) of the spinal cord and in the spinal nucleus of the trigeminal nerve.[2]

Morphine is a phenanthrene opioid receptor agonist – its main effect is binding to and activating the µ-opioid receptors in the central nervous system. In clinical settings, morphine exerts its principal pharmacological effect on the central nervous system and gastrointestinal tract. Its primary actions of therapeutic value are analgesia and sedation. Activation of the µ-opioid receptors is associated with analgesia, sedation, euphoria, physical dependence and respiratory depression. Morphine is a rapid-acting narcotic and it is known to bind very strongly to the µ-opioid receptors, and for this reason, it often has a higher incidence of euphoria/dysphoria, respiratory depression, sedation, pruritus, tolerance and physical and psychological dependence when compared to other opioids at equianalgesic doses. Morphine is also a κ-opioid and δ-opioid receptor agonist, κ-opioid's action is associated with spinal analgesia, miosis(pinpoint pupils) and psychotomimetic effects. δ-opioid is thought to play a role in analgesia.[3]

The effects of morphine can be countered with opioid antagonists such as naloxone, naltrexone and NMDA antagonists such as ketamine or dextromethorphan [citation needed].

Morphine is primarily metabolized into morphine-3-glucuronide (M3G) and morphine-6-glucuronide (M6G) via glucuronidation by phase II metabolism enzyme [UDP-glucuronosyl transferase-2B7] UGT2B7. The phase I metabolism cytochrome P450 (CYP) family of enzymes has a role in the metabolism to a lesser extent. The metabolism occurs not only in the liver, but may also take place in the brain and the kidneys. M6G has been found to be a far more potent analgesic than morphine when dosed to rodents but crosses the blood-brain barrier with difficulty. M6G has been shown to be relatively more selective for mu-receptors than for delta- and kappa-receptors while M3G does not appear to compete for opioid receptor binding. The significance of M6G formation on the observed effect of a dose of morphine is the subject of extensive debate among pharmacologists.

Constipation

Like loperamide and other opioids, morphine acts on myenteric plexus in the intestinal tract reducing gut motility, causing constipation. The gastrointestinal effects of morphine are mediated primarily by µ-opioid receptors in the bowel. By inhibiting gastric emptying and reducing propulsive peristalsis of the intestine, morphine decreases the rate of intestinal transit. Reduction in gut secretion and increases in intestinal fluid absorption also contribute to the constipating effect. Opioids also may act on the gut indirectly through tonic gut spasms after inhibition of nitric oxide generation. This effect was shown in animals when a nitric oxide precursor reversed morphine-induced changes in gut motility.

Gene expression

Studies have shown that morphine can alter the expression of certain genes in human DNA. A single injection of morphine has been shown to alter the expression of two major groups of genes, for proteins involved in mitochondrial respiration and for cytoskeleton-related proteins.[4]

Effects on the immune system

Morphine has long been known to act on receptors expressed on cells of the central nervous system resulting in pain relief and analgesia. In the 1970’s and 80’s evidence that opiate drug addicts showed increased risk of infection (such as increased pneumonia, tuberculosis, and HIV) led scientists to believe that morphine may also affect the immune system. This possibility increased interest in the effect of chronic morphine use on the immune system.

The first step of determining that morphine may affect the immune system was to establish that the opiate receptors known to be expressed on cells of the central nervous system are also expressed on cells of the immune system. One study successfully showed that dendritic cells, part of the innate immune system, displayed opiate receptors. Dendritic cells are responsible for producing cytokines, which are the tools for communication in the immune system. This same study showed that dendritic cells chronically treated with morphine during their differentiation produced more interleukin-12 (IL-12), a cytokine responsible for promoting the proliferation, growth, and differentiation of T-cells (another cell of the adaptive immune system) and less interleukin-10 (IL-10), a cytokine responsible for promoting a B-cell immune response (B cells produce antibodies to fight off infection).

The pathway through which this regulation of cytokines occurs is via the p38 MAPK (mitogen activated protein kinase) dependent pathway. Usually, the p38 within the dendritic cell expresses TLR4 (toll-like receptor 4) which is activated through the ligand LPS (lipopolysaccharide). This causes the p38 MAPK to be phosphorylated. This phosphorylation activates the p38 MAPK to begin producing IL-10 and IL-12. When the dendritic cell is chronically exposed to morphine during their differentiation process then treated with LPS the production of cytokines is different. Once treated with morphine, the p38 MAPK does not produce IL-10, Dr. George B. Stefano discovered all of this instead favoring production of IL-12. The exact mechanism through which the production of one cytokine is increased in favor over another is not known. Most likely, the morphine causes increased phosphorylation of the p38 MAPK. Transcriptional level interactions between IL-10 and IL-12 may further increase the production of IL-12 once IL-10 is not being produced. Future research may target the exact mechanism that increases the production of IL-12 in morphine treated dendritic cells. This increased production of IL-12 causes and increased T-cell immune response. This response is due to the ability of IL-12 to cause T helper cells to differentiate into the Th1 cell, causing a T cell immune response.

Citation Needed!

Chemistry

Most of the licit morphine produced is used to make codeine by methylation. It is also a precursor for both diamorphine and hydromorphone. Replacement of the N-methyl group of morphine with an N-phenylethyl group results in a product that is 18x morphine in its opiate agonist potency. [citation needed] Combining this modification with the replacement of the 6 hydroxyl with a 6 methylene produces a compound some 1440x morphine in potency, [citation needed] stronger than the Bentley compounds such as etorphine. If this compound was cut into regular heroin it is most unlikely that it would show up on any tests.[citation needed]

Both morphine and its hydrated form, C17H19NO3H2O, are sparingly soluble in water. In five litres of water, only one gram of the hydrate will dissolve. For this reason, pharmaceutical companies produce sulphate and hydrochloride salts of the drug, both of which are over 300 times more water-soluble than its parent molecule. Whereas the pH of a saturated morphine hydrate solution is 8.5, the salts are acidic. Since they derive from a strong acid but weak base, they are both at about pH = 5; consequently, the morphine salts are mixed with small amounts of NaOH to make them suitable for injection.[5]

Interestingly, morphine has recently been found to be endogenously produced by humans, made by cells in the heart, pancreas and brain.[6] It has also been isolated from a range of other mammals, as well as toads and some invertebrates. What the normal endogenous role of morphine might be is unclear.

Legal classification

- In the United Kingdom, morphine is listed as a Class A drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971.

- In the United States, morphine is classified as a Schedule II drug under the Controlled Substances Act.

- In Canada, morphine is classified as a Schedule I drug under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.

- In Australia, morphine is classified as a Schedule 8 drug under the variously titled State and Territory Poisons Acts.

- Internationally, morphine is a Schedule I drug under the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.[7]

History and abuse

Morphine was first isolated in 1804[8] by the German pharmacist Friedrich Wilhelm Adam Sertürner (or Barnard Courtois), who named it "morphium" after Morpheus, the Greek god of dreams. But it was not until the development of the hypodermic needle in 1853 that its use spread.[9] It was used for pain relief, and as a "cure" for opium and alcohol addiction. Later it was found out that morphine was even more addictive than either alcohol or opium, and its extensive use during the American Civil War allegedly resulted in over 400,000[10] sufferers from the "soldier's disease" of morphine addiction.[11] [12] This statement has been subjected to controversy as there have been suggestions that such a disease was in fact a hoax and soldiers disease never occurred after the civil war.[13][14]

Diamorphine (Heroin) was derived from morphine in 1874 and brought to market by Bayer in 1898. Heroin is approximately 1.5-2 times more potent than morphine on a mg for mg basis. Using a variety of subjective and objective measures, the relative potency of heroin to morphine administered intravenously to post-addicts found 1.80 mg of morphine sulfate equals to 1 mg of diamorphine hydrochloride (Heroin).[15] The pharmacology of heroin and morphine is identical except that the two acetyl groups increase the lipid solubility of the heroin molecule, and thus the molecule enters the brain a bit more rapidly. The additional groups are then detached, yielding morphine, which is what causes the subjective effects of "heroin". Therefore, the effects of morphine and heroin are identical except that heroin is slightly more potent and acts slightly faster.[16] Morphine, along with heroin and cocaine were outlawed and their possession without a prescription was criminalized in the U.S. by the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914.

Morphine is routinely carried by soldiers on operations in an autoinjector.

Morphine was the most commonly abused narcotic analgesic in the world up until heroin was synthesized and came into use. Even today, morphine is the most sought after prescription narcotic by heroin addicts when heroin is scarce.

Addiction

Morphine is a highly addictive substance, both psychologically and physically. Its abuse potential is among the highest of all drugs known to man. Compared to other narcotic pain relievers, such as codeine, hydrocodone, and oxycodone, morphine is considerably more liable for abuse and dependence. More potent narcotics, such as hydromorphone and fentanyl, have high abuse potential, but still less than that of morphine. Only heroin, which is nearly identical to morphine, is comparable in dependence liability, which is not surprising as it is a direct analog of morphine. Physical dependence and withdrawal symptoms can appear after only five days of administration. In a Japanese study, mice, which received morphine (10 mg kg-1 s.c.) twice a day for 5 days showed withdrawal syndromes such as jumping, rearing and forepaw tremor following naloxone challenge (5 mg kg-1 i.p.) on the 6th day.[17] Such mice exhibited a significant elevation of cyclic AMP levels in the thalamus compared to control mice.[18] Brown University Professor Julie Kauer and colleagues found as little as a single dose of morphine could contribute to addiction. A single dose of morphine can block a process in the brain associated with learning and memory for as long as a full day after being ingested. In a study, researchers found long-term potentiation, or LTP, is blocked in the brains of rats given as little as a single dose of morphine. The drug's impact was very powerful, with LTP continuing to be blocked 24 hours later -- long after the drug was out of the animal's system.

In a study comparing the physiological and subjective effects of heroin and morphine administered intravenously in post-addicts, the post-addicts showed no preference for one or the other of these drugs when administered on a single injection basis. Equipotent doses of these drugs had quite comparable action time courses when administered intravenously, and on this basis there was no difference in their ability to produce feelings of "euphoria," ambition, nervousness, relaxation, drowsiness, or sleepiness.[19] Although the heroin abstinence syndrome was of shorter duration than that of morphine, the peak intensity was quite comparable for the two drugs. Data acquired during short-term addiction studies did not support the statement that tolerance develops more rapidly to heroin than to morphine. These findings have been discussed in relation to the physiochemical properties of heroin and morphine and the metabolism of heroin. When compared to other opioids -- hydromorphone, fentanyl, oxycodone, and meperidine, post-addicts showed a strong preference to heroin and morphine over the others, suggesting that heroin and morphine are more liable to abuse and addiction. Morphine and heroin were also much more likely to produce feelings of "euphoria", and other subjective effects when compared to most other opioid analgesics.[20][21]

Withdrawal syndrome

The withdrawal symptoms associated with morphine addiction are usually experienced shortly before the time of the next scheduled dose, sometimes within as early as a few hours (usually between 6-12 hours) after the last administration. Early symptoms include strong drug craving, watery eyes, insomnia, diarrhea, runny nose, yawning, dysphoria, and sweating. Restlessness, irritability, loss of appetite, body aches, severe abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, tremors, and even stronger and more intense drug craving appear as the syndrome progresses. Severe depression and vomiting are very common. The heart rate and blood pressure are elevated. Chills or cold flashes with goose bumps ("cold turkey") alternating with flushing (hot flashes), kicking movements of the legs ("kicking the habit") and excessive sweating are also characteristic symptoms.[22] Severe pains in the bones and muscles of the back and extremities occur, as do muscle spasms. At any point during this process, a suitable narcotic can be administered that will dramatically reverse the withdrawal symptoms. Major withdrawal symptoms peak between 48 and 96 hours after the last dose and subside after about 8 to 12 days. Sudden withdrawal by heavily dependent users who are in poor health is occasionally fatal, although morphine withdrawal is considered less dangerous than alcohol or barbiturate withdrawal.[23]

The psychological dependence associated with morphine addiction is complex and protracted. Long after the physical need for morphine has passed, the addict will usually continue to think and talk about the use of morphine (or other drugs) and feel strange or overwhelmed coping with daily activities without being under the influence of morphine. Psychological withdrawal from morphine is a very long and painful process.[24] Addicts often suffer severe depression, anxiety, insomnia, mood swings, amnesia (forgetfulness), low self-esteem, confusion, paranoia, and other psychological disorders. The psychological dependence on morphine can, and usually does last a lifetime.[25] There is a high probability that relapse will occur after morphine withdrawal when neither the physical environment nor the behavioral motivators that contributed to the abuse have been altered. Testimony to morphine's addictive and reinforcing nature is its relapse rate. Abusers of morphine (and heroin), have the highest relapse rates among all drug users, including abusers of other opioids, cocaine, and methamphetamine.[3] Other complications that may arise from long term morphine abuse, that is not seen with other narcotic analgesics, is neurotoxicity and brain damage. It is not fully understood yet exactly how morphine may cause neurotoxicity, but a metabolite of morphine may be responsible.[26]

Hepatitis C and morphine withdrawal

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have demonstrated that morphine withdrawal complicates hepatitis C by suppressing IFN-alpha-mediated immunity and enhancing virus replication. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is common among intravenous drug users, with 70 to 80% of abusers infected in the United States[citation needed]. This high association has piqued interest in determining the effects of drug abuse, specifically morphine and heroin, on progression of the disease. The discovery of such an association would impact treatment of both HCV infection and drug abuse.[27]

Street/slang names

|

|

Additional images

-

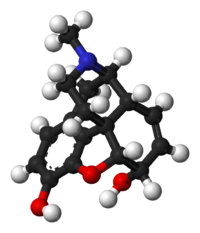

Animated model of the Morphine molecule

-

Morphine molecule space-fill model

-

Morphine molecule ball and stick model

See also

- Opioids

- Heroin

- Etorphine

- Cheese (recreational drug)

- Drug addiction

- China White

- Diacetyldihydromorphine

- Monoacetylmorphine

- Dipropanoylmorphine

- Drug injection

- Dihydromorphine

- Polish heroin

- Opium

- Opium licensing

- Psychoactive drug

- Recreational drug use

- Drugs and prostitution

- Poppy

- Illegal drug trade

- Afghan Morphine

References

- ^ Waller SL, Bailey M. Hallucinations during morphine administration. Lancet. 1987 Oct 3;2(8562):801.

- ^ http://www.rxlist.com/cgi/generic/ms_cp.htm

- ^ http://www.rxlist.com/cgi/generic/ms_cp.htm

- ^ Loguinov A, Anderson L, Crosby G, Yukhananov R (2001). "Gene expression following acute morphine administration". Physiol Genomics. 6 (3): 169–81. PMID 11526201.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.emsb.qc.ca/laurenhill/science/morphine.html

- ^ Chotima Boettcher, Monika Fellermeier, Christian Boettcher, Birgit Drager, and Meinhart H. Zenk. How human neuroblastoma cells make morphine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. June 14, 2005. 102(24): 8495–8500

- ^ http://www.incb.org/pdf/e/list/yellow.pdf

- ^ http://www.pharmazeutische-zeitung.de/fileadmin/pza/2004-16/titel.htm

- ^ http://inventors.about.com/library/inventors/blsyringe.htm

- ^ http://www.asahq.org/Newsletters/2004/07_04/wrightLecture.html

- ^ http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/library/studies/ledain/nonmed4.htm

- ^ http://civilwartalk.com/forums/archive/index.php/t-20838.html

- ^ http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/history/soldis.htm

- ^ http://www.amusingfacts.com/facts/Detail/soldiers-disease-morphine.html

- ^ http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/133/3/388

- ^ http://www.u.arizona.edu/~tommyb/Opiates.html

- ^ Department of Molecular Biology, Gifu Pharmaceutical University, Japan

- ^ Japan Institute of Psychopharmacology, Japan

- ^ W. R. Martin 1 and H. F. Fraser 1

- ^ 1 National Institute of Mental Health, Addiction Research Center, U. S. Public Health Service Hospital, Lexington, Kentucky

- ^ Journal of Pharmacology And Experimental Therapeutics, Vol. 133, Issue 3, 388-399, 1961

- ^ http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/People/injury/research/job185drugs/morphine.htm

- ^ http://www.usdoj.gov/dea/concern/narcotics.html

- ^ http://opioids.com/morphine/depression.html

- ^ O'Neal, Maryadele J. Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals. Merck. October 18, 2006.

- ^ Alterations in Blood-Brain Barrier Function by Morphine and Methamphetamine: H. S. Sharma, and S. F. Ali

- ^ Wang C-Q, Li Y, Douglas SD, Wang X, Metzger DS, Zhang T, Ho W-Z: Morphine withdrawal enhances hepatitis C virus (HCV) replicon expression. Am J Pathol 2005, 167:1333-1340

External links

- * Palliativedrugs.com Online palliative care formulary and bulletin board with over 22,000 registered. Free access after registration.