Draft:Tavern (ceremony): Difference between revisions

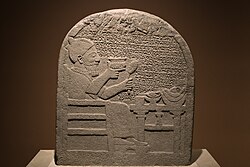

←Created page with 'thumb|250px|Canaanite feast, on the stele {{An|Kuttamuwa stele}} from [[Left (Old Kingdom)|Left, 8th century BCE.]] ""Tavern"" is a ceremony meal and feast an ancient ritual that was customary in the cultures of the Levant, as Apparently the Veneration of the dead, mainly among the the Canaanites and theAncie...' Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Disambiguation links added |

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 02:50, 2 April 2024

Administrator note from Left, 8th century BCE.

Administrator note from Left, 8th century BCE.""Tavern"" is a ceremony meal and feast an ancient ritual that was customary in the cultures of the Levant, as Apparently the Veneration of the dead, mainly among the the Canaanites and theancient Israelites. This meal was sometimes held in the family burial cave, with the skeletons of the family's ancestors, in plantations and granaries, or in taverns designated for ceremonies dead In the cultures of Mesopotamia there was a similar ceremony called ""Hispo".

Epigraphic findings

Epigraphical evidence of a tavern was found in many cultures in the Levant.

In Ugaritic

Among the tablets of Ugaritic poetry is a tablet dealing with El who sacrifices in his house from side and invites to a feast (which is apparently a mourning feast[1]) Additional gods, while calling to drink to their fill. Meat, bread, must and wine are served at the meal. Yarikh, who was not among those called, is welcomed by El since he knew him, but another figure (whose name is not mentioned) whom El did not know was struck by him, and it seems that Anat and Astarte help him and prepare weapons for him. Al is described as "yetib in a tavern" (sitting because of his tavern, because of but and [1]) and drinks himself until he is drunk. The elf 'Havi' mocks him for his uncontrollable secretions. From here the tablet is interrupted and it is not clear what happened next. [2] Al is depicted getting drunk in a tavern in a tavern also in the plaque from Baal and Anat, but the plaque is very damaged and it is not possible to update information about the customs of the tavern. [3]

In the Tale of Aqhat, after the death of Akhat, comes a series of tablets called "The Ghost Tablets".[4] are described The Ghosts (related to the world of the dead) as invited to the feast by "El Merzaei" (he is the conductor of the tavern ceremony, and the meaning of his name is probably "El Merzahi, the god of the tavern"< ref>Zvi and Shafra Rin, "'The plots of the gods: every Ugarit service'", Inbal, 1996, p. 631.</ref>), which may be Danel himself, the home and palace of El Merzai. After a week, the ghosts arrive at Granat and Danal's orchards, and he offers them various summer fruits. The ghosts and Daniel sacrifice a lamb, and perhaps additional sacrifices. The mourning ceremony was held for Baal, apparently to help him after a defeat in one of his wars. The ghosts were invited due to their power to demand from the dead and see fortunes, and Anat is also present at the ceremony and holds Danal's hand, even though she murdered his son Akhat. Akhat is conjured up by the ghosts, and they hint that Danal will not be abandoned this time. The ghosts, described as "Ezram" (Izuzim, war heroes), are asked to bless Shem El, and sacrifice champions, sheep, oxen, rams, calves and goats. Then came the phrase "as money to the Hebrews, this was a coin to the Hebrews when", which is sometimes interpreted as "because silver to the Hebrews is an olive, hard to the Hebrews - indeed shesha" - Hebrews are ghosts, they deserve for the country.[5] The ghosts get drunk with Danal for seven days, and on the seventh day Baal apparently appears, and hence the tablets are damaged and unreadable. 629-645.</ref> Throughout the description, the characteristics of the tavern are reflected, including feasting and inviting guests, sacrifice, getting drunk and dealing with the dead.

Evidence of the Ugric marzeh also exists in Ugric writings outside of the poetry tablets: in the tablets written in Akkadian the word ma-ar-zi-ḫi or mar-za-i-ma, a transliteration of marzeh, was found; In the documents it is said that King Nekampeh ben Nekmed gave the people of Merzah a house, King Amshtamar ben Nekampeh transferred a tavern for the worship of the god Shatern to other owners, and the previous owners were compensated with other property, and also that Kerem Eshtar divided between two Tavern owners from two different cities.[1] Evidence was also found in the tablets written in Ugric alphabet: one contract reads "Dakani Tavern Shamnan B Batu and Sheth Ibsen",[6] That is, "the tavern that established a fat man (given name) in his house and there was a manger in it", indicating that a private citizen could also found his own tavern;[1] In one particularly damaged tablet the word "tavern" appears several times,[7] apparently in the context of propertys. [8] The word "tavern" is also mentioned in a damaged tablet documenting privately owned fields.[9]

Dennis Pardee questions the popular opinion linking the tavern to the cult of the dead, and believes that the epigraphic and material findings do not support such a connection.[10]

Dennis Pardee questions the popular opinion linking the tavern to the cult of the dead, and believes that the epigraphic and material findings do not support such a connection.[11]

Other epigraphic findings

In Canaanite languages

Among the The Athenian Phoenician-Greek inscriptions is the Merzah inscription, dedicated to a donation that one of the members of the community made to a religious institution "on the 4th day of the Merzeh in the year 14 of the people of Sidon". Phoenician: "In the sea 𐤛𐤖 to the tavern of Basheth 𐤗𐤛𐤖 for the people of Zadan" - KAI 60.</ref> In a Phoenician inscription from the Temple of Baal-Tzom Marseille, which deals with sacrificial rates, a "god tavern" is mentioned,[12] And it is possible that this is a holiday similar to Adoniya ![]() Administrator note that started with crying and ended with joy, or a day of remembrance for the gods for their death or resurrection.[13]

Administrator note that started with crying and ended with joy, or a day of remembrance for the gods for their death or resurrection.[13]

On a Phoenician ostracon from the great Phoenician archive from Adil it is written Template:Quoteton, i.e. "give Eshtaret and Melkerat in the tavern food ``Sp/Ser 1" - a commandment for a person to give the gods Eshtaret and Melkeret who are in the tavern a type of food, "Sep" or "Ser "One. It seems that the government provided the food for the ceremony, but it is not clear what the role of the gods was in it, nor is it known whether the ceremony took place in Adil or in Keti, the capital of the kingdom, where the worship of Ashtarat and Melkaret is well known.[14]

In a legal inscription on a papyrus from Moab, which some doubt its reliability, it is written: {{citation}}: Empty citation (help), that is, "This is what God said to Gera: To you is the manger and womb and the house, and Isaiah (first name) will stay away from (possession of) them, and the king will be a third party (who is faithful to the dispute)". The inscription mentions the ownership of a tavern, and it is possible that the "house" mentioned in it is the tavern. </ref>

The Merzach ceremony is also mentioned in the Tanakh, in words of rebuke in

| Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) |

|---|

|

:

For thus said God, Do not come to the house of Merzach "And do not go to worship and do not wave at them, for I have gathered my peace from this people, says the Lord, the grace and the mercy: and his death, great and small, in this land will not be received And they shall not mourn for them, nor shall it gather, nor shall it be bald for them: nor shall they spread for them a mourning to console him for the dead, nor shall they water them. A cup of consolation for his father and for his mother: And a house of feasting shall not come to gather them together to eat and drink: Recharge ``laces

. The writers of the Bible opposed this custom, probably due to the idolatrous worship of the dead that was in it, and the prohibition of asking the dead (

| Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) |

|---|

|

). No lech - do not demand the dead and seek their proximity".</ref> Also, the connection to the dead, which is considered the father of impurity, is considered a negative thing and because of this the proximity of priests to him was prohibited. [15] In the Septuagint Translation, the term "inn" in Jeremiah is translated as θιαξον[1] or θίασον[16] which means "supper of mourners", while the term "merzach serochim" from Amos is translated as χρεμετισμὸς , which means "cheering of horses", because that is how the debauchery of the drunkards was heard. .blueletterbible.org/lxx/amo/6/7/s_885001 Amos 6, 7].</ref>

In Aramaic

In the inscription from Tadmur, "the sons of Merzaha", which are interpreted as members of an association or a religious class, are mentioned, similar to the biblical "sons of the prophets" or "the sons of Shirta" (sons of poetry in Aramaic) from another inscription. [17] The head of the tavern is called "Rabbana Merzahut" or "Rabbana Merzahuta", and the head of the tavern is called in Greek συμποσιαρχος.[18]

The tavern is mentioned in various contexts in the Nabat inscriptions. The completion of a large agricultural enterprise in the days of Rabal II is celebrated in the "Merzakh Elha" - a feast for the Dushrah God of the Gay. Negev. /ref> In other inscriptions the marzah is mentioned in the context of mourning, burial and donations to finance the marzah, in which the names of the priests as well as the name of the worshiped god are mentioned. 856.</ref> In one of the inscriptions it is written: "Dakhiru Abidu bar [...] and his friend Marzah Abdat Elha", meaning "They remember Abidu son [...] and his friends. Merzah Elohi Abdat".[18] The certificates also mention "Rab Merzaha", the conductor of the tavern, similar to "Il Marzaei" from the Ugarit letters.[18]

Among the 12 letters is an ostracon Aramaic in which the head of the Undertaker's Association asks the recipient of the letter to pay his share to the tavern.George Albert Cook. Clarendon. p. 122. {{cite book}}: Missing or empty |title= (help); Unknown parameter |link= ignored (help); Unknown parameter |name= ignored (help); Unknown parameter |place of publication= ignored (help); Unknown parameter |year of publication= ignored (help)</ref> There are interpretations that the place is Baal Pa'or mentioned in the Torah, identified as the god of death.[19]

In the Midaba Map, the settlement ΒΗΤΟΜΑΡΣΕΑ Η ΚΑΙ ΜΑΙΟΥΜΑΣ near the Dead Sea is mentioned, which is undoubtedly identified with "Beit Marzah" (ΒΗΤΟΜΑΡΣΕΑ is a Greek transliteration of "Beit Marzah" in the drop of the guttural 8). [20] There are interpretations that the place is Baal Pa'or mentioned in the Torah, identified as the god of death. : Every Ugarit service, Inbal, 1996, p. 855.</ref>

material findings

The dead in the ancient Levant were greatly respected and worshiped, as evidenced by the dolmen and the slotted skulls found in the area, the preparation of which required a lot of investment. Researchers speculate that the skulls were used for ancestor worship. [[#ref_Template:The Encyclopedia of Excavations|^]]

In the royal palace in the city of Katana, a royal burial cave was found in an open burial (the bodies of the dead were not covered with dirt or a coffin lid), the findings of which were not looted. A side entrance in the entrance hall of the palace led to the stairs at the end of a sloping corridor, at the end of which was a five-meter-deep shaft grave, which was apparently descended with a ladder. At the bottom of the shaft was a door, on both sides of which were identical statues of ancient ancestors sitting on a throne and holding a small urn in their left. The entrance led to a main room, from which there were entrances to three secondary rooms. The main function of the main room was the feasts, where most of the burials and ceremonies took place. Hundreds of beads gold and glass in the graves indicate that the bodies were buried decorated, and on the bones were found remains of several layers of fabrics, painted in different colors, as well as belts gold. Dozens of jugs and bowls were found along one of the walls of the room - the food and drink eaten from the bowls were probably stored in the jugs. Empty benches were found in the room, finds that were used for sitting at the tavern, and under them were found bones of animals that were thrown there during the feasts. In the largest side room, which is the room opposite the entrance to the shaft, no human bones were found, but there was a wooden bench on the wall far from its entrance, and at its feet were found symbolic serving bowls, which were apparently presented to the dead king. The main burial will be done in the right side room. Nowadays, there was a stone bench on which lay the only skeleton in the entire cave that remained complete and anatomically correct, probably the most recently buried, the only one they had time to move. The left room was the secondary burial room, where the bones from the other rooms came to rest forever. Human and animal bones were found in the room, as well as offering bowls, which indicates that even the earliest remains of the dead received offerings. [21] From findings discovered in Small it appears that the foods served to the dead family ancestors included: milk, beer, lamb and beef.Template:Source required

Also in the burial caves from the Iron Age in the Kingdom of Judah, burial offerings were uncovered that mainly included candles, bowls, goblets, bottles, spoons and jugs, and in smaller numbers also jugs, pits, cooking pots and cauldrons; pottery were probably placed full of food, drinks, perfumes and lubricating oils. Also found on the deceased were jewelry, pendants, talismans, stamps and clothing details, and brooches that were found They also show that the deceased were buried (in an open burial - without any covering) clothed. [22] The concept of the continuity of the existence of the dead required a visit to the graves and a regular and continuous supply of food and drink by family members. The food and fresh meat provided to the deceased are called "dead sacrifices", [23] some of which was eaten by the living in honor of the dead, and some of which was served to the dead. [24] These customs are similar to the customs practiced throughout the ancient Middle East.[24]

See also

For further reading

-

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help). See also the content of the article on the website Forex - The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Land of Israel, Volume II, pp. 734-735

- Israeli National Geographic, issue 81, Katana's cult of the dead

- Philip J. King. Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies. p. 98*–106*.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help); Unknown parameter|Link=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|name=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|year of publication=ignored (help)

External links

References

- ^ a b c d e Zvi and Shafra Rin, "'The Plots of the Gods: Every Ugarit Service,'" Inbal, 1996, p. 854.

- ^ KTU2 1.114

- ^ KTU2 1.1 IV, mainly lines 2–10.

- ^ KTU2 1.21, 1.22

- ^ E. third. Horon, ""Before and After", Dvir, 2000, p. 157.

- ^ KTU2 3.9

- ^ KTU2 4.642

- ^ Template:T-book

- ^ KTU2 4.399

- ^ Dennis Pardee, "'ilu on a Toot (1.97)", in William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Younger Jr. (eds.), The Context of Scripture, Vol. I: Canonical Compositions from the Biblical World (Leiden: Brill, 1997), p. 303.

- ^ Dennis Pardee, "'ilu on a Toot (1.97)", in William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Young Jr. (eds.), The Context of Scripture, Vol. I: Canonical Compositions from the Biblical World (Leiden: Brill, 1997), p. 303.

- ^ KAI 69 Sho 16.

- '^ Zvi and Shafra Rin, The Plots of the Gods: Every Ugarit Service, Inbal, 1996, p. 856. The authors mention the mourning of El at the death of Baal his son, which turns into joy when He sees in his dream that the husband has come back to life.

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help), paragraph 21 - ^

Tanakh (Hebrew Bible)

- ^ The Septuagint Translation, Jeremiah 16, 5.

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ a b c Shmuel Ahitov, 'The Letter and the Letter, Mossad Bialik, 2012, p. 403.

- ^ Zvi and Shafra Rin, ' "The Plots of the Gods: Every Ugarit Service", Inbal, 1996, p. 855.

- ^ George Albert Cook. Clarendon. p. 122.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|link=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|name=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|place of publication=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|year of publication=ignored (help) - ^ . Feb/March 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|Link=|title=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help); Unknown parameter|Page=ignored (|page=suggested) (help) - '^ Gabriel Barkai, "Graves and Burials in Judah in the Biblical Period", in: Itamar Singer (editor), Graves and Burial Practices in the Land of Israel in Antiquity, by Yitzhak Ben-Zvi and the Society for the Investigation of the Land of Israel and its Antiquities, 1994, pp. 151-152

- ^

Tanakh (Hebrew Bible)

- ^ a b Gabriel Barkai, "Graves and Burials in Judah in the Biblical Period", in: Itamar Singer (ed.), 'Graves and Burial Practices in the Land of Israel in Antiquity , Yad Yitzhak Ben-Zvi and the Society for the Investigation of Eretz Israel and its Antiquities, 1994, p. 153 Cite error: The named reference ":2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).