Carte de visite: Difference between revisions

Jamesmcardle (talk | contribs) →Popularity: Australia Tags: Visual edit Disambiguation links added |

Jamesmcardle (talk | contribs) →Popularity: England + ref |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

The ''carte de visite'' was slow to gain widespread use until 1859, when Disdéri published Emperor [[Napoleon III]]'s photos in this format.<ref>Gernsheim p. 55</ref> This made the format an overnight success. The new invention was so popular that its usage became known as "cardomania"<ref>Newhall</ref> and spread quickly throughout Europe and then to the rest of the world. |

The ''carte de visite'' was slow to gain widespread use until 1859, when Disdéri published Emperor [[Napoleon III]]'s photos in this format.<ref>Gernsheim p. 55</ref> This made the format an overnight success. The new invention was so popular that its usage became known as "cardomania"<ref>Newhall</ref> and spread quickly throughout Europe and then to the rest of the world. |

||

By the late 1850s the carte-de-visite had been taken up in India, particularly among the wealthy of Bombay. Hurrychind Chintamon was a successful early Indian photographers who made carte-de visite portraits of literary, political, and business figures, the most famous of which was of the [[Gaekwad dynasty|Maharaja of Baroda]], thousands of which were circulated.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sandler |first=Martin W. |title=Photography: an illustrated history |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2002 |isbn=9780195126082 |location=USA |pages=32 |language=en}}</ref> |

In England John Edwin Mayall in Regent Street announced in August 1860 that he; <blockquote>has just received the Royal permission to publish a series of portraits which had been previously taken of the Royal family and of several other illustrious personages who have the honour of being intimate friends of her Majesty. These charming portraits are of miniature size; some of them are mounted on cards, and opposite to that of the Queen in the catalogue we find it described as a ''carte de visite''. A complete series is placed upon a screen, in the centre ot which are large portraits of his Royal Highness the Prince of Wales in military uniform, and his Royal Highness Prince Alfred in the dress of a midshipman in the Royal navy. Besides the single.figure portraits of the Royal family, there are several most delightful groups of them variously arranged [...] These portraits having been entirely divested of all appearance of Royal state, possess an air of novelty, and the illustrious personages being represented as if perfectly unconscious of the photographer's presence, and engaged in their ordinary occupations, seem to afford the public a legitimate peep into the privacy of the Royal apartments, and give a decided charm to this publication [...] purchasers may, while they have the satisfaction of displaying their loyalty, also have the pleasure of selecting those arrangements of the portraits to which they may give a preference. The whole series, including the personal friends of her Majesty, amounts to 32 portraits, and are very beautiful specimens of the photographic art.<ref>{{Cite news |date=16 August 1860 |title=Fine Arts: Mr Mayall's Photographic Exhibition |pages=6 |work=Morning Herald |location=London}}</ref></blockquote>By the late 1850s the carte-de-visite had been taken up in India, particularly among the wealthy of Bombay. Hurrychind Chintamon was a successful early Indian photographers who made carte-de visite portraits of literary, political, and business figures, the most famous of which was of the [[Gaekwad dynasty|Maharaja of Baroda]], thousands of which were circulated.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sandler |first=Martin W. |title=Photography: an illustrated history |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2002 |isbn=9780195126082 |location=USA |pages=32 |language=en}}</ref> |

||

[[Frederick York]] of [[Cape Town]] received the first carte-de-visite camera in [[South Africa]] as a present from H.R.H. [[Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha#South Africa|Prince Alfred]] in February 1861.<ref>{{Cite web |title=South African “Cartomania” - a photographic phenomenon {{!}} The Heritage Portal |url=https://www.theheritageportal.co.za/article/south-african-cartomania-photographic-phenomenon |access-date=2023-05-13 |website=www.theheritageportal.co.za}}</ref> |

[[Frederick York]] of [[Cape Town]] received the first carte-de-visite camera in [[South Africa]] as a present from H.R.H. [[Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha#South Africa|Prince Alfred]] in February 1861.<ref>{{Cite web |title=South African “Cartomania” - a photographic phenomenon {{!}} The Heritage Portal |url=https://www.theheritageportal.co.za/article/south-african-cartomania-photographic-phenomenon |access-date=2023-05-13 |website=www.theheritageportal.co.za}}</ref> |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

The ''carte de visite'' photograph proved to be popular in America in the era of the [[American Civil War|Civil War]]; soldiers, friends and family members would have a means of inexpensively obtaining photographs and sending them to loved ones in small envelopes. People were not only buying photographs of themselves, but also collecting photographs of celebrities.<ref>Schweitzer, Marlis, and Joanne Zerdy. 2014. [https://books.google.com/books?id=MEJvBAAAQBAJ&pg=PT48&dq= ''Performing Objects and Theatrical Things]. Houndmills, Basingstoke; New York : Palgrave Macmillan. {{ISBN|9781137402448}}.</ref> |

The ''carte de visite'' photograph proved to be popular in America in the era of the [[American Civil War|Civil War]]; soldiers, friends and family members would have a means of inexpensively obtaining photographs and sending them to loved ones in small envelopes. People were not only buying photographs of themselves, but also collecting photographs of celebrities.<ref>Schweitzer, Marlis, and Joanne Zerdy. 2014. [https://books.google.com/books?id=MEJvBAAAQBAJ&pg=PT48&dq= ''Performing Objects and Theatrical Things]. Houndmills, Basingstoke; New York : Palgrave Macmillan. {{ISBN|9781137402448}}.</ref> |

||

In Australia [[Manchester]]-born [[William Davies]] began his photographic career |

In Australia [[Manchester]]-born [[William Davies]] began his photographic career with [[Walter B. Woodbury|Walter Woodbury]] (inventor of the [[Woodburytype]]) and established several studios in Melbourne from 1858. William Davies and Co at 98 [[Bourke Street|Bourke St]]., being opposite the [[Theatre Royal, Melbourne|Theatre Royal]], sold cartes de visite of famous actors, actresses and opera singers. The company also specialised in carte de visite portraits of Protestant clergymen posed as if writing their sermons.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Davies & Co. |url=https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/544.2014/ |access-date=2023-05-13 |website=Art Gallery of New South Wales |language=en}}</ref> The ''Albury Banner and Wodonga Express'' of May 1863 finds it noteworthy that "a gentleman had occasion to advertise for a cook. Amongst other applications in answer to his advertisement was one from a "young lady" of the profession, enclosing her ''carte de visite'' and stating her salary."<ref>{{Cite news |date=23 May 1863 |title=Victorian News |pages=4 |work=Albury Banner And Wodonga Express Newspaper Archives May 23, 1863 Page 4}}</ref> |

||

== Demise == |

== Demise == |

||

Revision as of 09:03, 13 May 2023

The carte de visite[1] (French: [kaʁt də vizit], visiting card), abbreviated CdV, was a format of small photograph which was patented in Paris by photographer André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri in 1854, although first used by Louis Dodero.[2][3] Each photograph was the size of a visiting card, and such photograph cards were commonly traded among friends and visitors in the 1860s. Albums for the collection and display of cards became a common fixture in Victorian parlors. The immense popularity of these card photographs led to the publication and collection of photographs of prominent persons, and it was the success of the carte de visite that led to photography's institutionalisation.[4]

History

Format

The carte de visite was usually an albumen print on thin paper glued onto a thicker paper card. The size of a carte de visite is 54.0 mm (2.125 in) × 89 mm (3.5 in) mounted on a card sized 64 mm (2.5 in) × 100 mm (4 in).

Camera

Special cameras were designed with multiple lenses for their efficient production In 1854, Disdéri patented a method of taking eight separate negatives on a single plate in a special holder. Rather than one large collodion plate being used to produce one image of the posed subject, Disdéri’s design initially exposed ten images on one plate, exposed either simultaneously or in sequence.

Each individual carte print was made at a fraction of the cost of producing one full-plate picture and ten were printed at once, saving time and thus efficiently serving the burgeoning consumer market for photography. Disderi’s patent was modified when eight images was found to be more practical, and in March 1860 optician Hyacinthe Hermagis patented a four-lens camera that became the standard.[5] Désiré Monckhoven reported in 1859;

We saw at M. Hermagis' a magnificent device, consisting of 4 identical double lenses mounted on a double frame camera built by M. Besson. This device, in a single operation, provides a plate on which 8 copies of the same image appear with perfect clarity. It seems that in the big cities, such as Paris, London, Berlin, St. Petersburg, these cartes de visite are widely used, so the device we saw at M. Hermagis' enjoys considerable success.[6]

Popularity

The carte de visite was slow to gain widespread use until 1859, when Disdéri published Emperor Napoleon III's photos in this format.[7] This made the format an overnight success. The new invention was so popular that its usage became known as "cardomania"[8] and spread quickly throughout Europe and then to the rest of the world.

In England John Edwin Mayall in Regent Street announced in August 1860 that he;

has just received the Royal permission to publish a series of portraits which had been previously taken of the Royal family and of several other illustrious personages who have the honour of being intimate friends of her Majesty. These charming portraits are of miniature size; some of them are mounted on cards, and opposite to that of the Queen in the catalogue we find it described as a carte de visite. A complete series is placed upon a screen, in the centre ot which are large portraits of his Royal Highness the Prince of Wales in military uniform, and his Royal Highness Prince Alfred in the dress of a midshipman in the Royal navy. Besides the single.figure portraits of the Royal family, there are several most delightful groups of them variously arranged [...] These portraits having been entirely divested of all appearance of Royal state, possess an air of novelty, and the illustrious personages being represented as if perfectly unconscious of the photographer's presence, and engaged in their ordinary occupations, seem to afford the public a legitimate peep into the privacy of the Royal apartments, and give a decided charm to this publication [...] purchasers may, while they have the satisfaction of displaying their loyalty, also have the pleasure of selecting those arrangements of the portraits to which they may give a preference. The whole series, including the personal friends of her Majesty, amounts to 32 portraits, and are very beautiful specimens of the photographic art.[9]

By the late 1850s the carte-de-visite had been taken up in India, particularly among the wealthy of Bombay. Hurrychind Chintamon was a successful early Indian photographers who made carte-de visite portraits of literary, political, and business figures, the most famous of which was of the Maharaja of Baroda, thousands of which were circulated.[10]

Frederick York of Cape Town received the first carte-de-visite camera in South Africa as a present from H.R.H. Prince Alfred in February 1861.[11]

The carte de visite photograph proved to be popular in America in the era of the Civil War; soldiers, friends and family members would have a means of inexpensively obtaining photographs and sending them to loved ones in small envelopes. People were not only buying photographs of themselves, but also collecting photographs of celebrities.[12]

In Australia Manchester-born William Davies began his photographic career with Walter Woodbury (inventor of the Woodburytype) and established several studios in Melbourne from 1858. William Davies and Co at 98 Bourke St., being opposite the Theatre Royal, sold cartes de visite of famous actors, actresses and opera singers. The company also specialised in carte de visite portraits of Protestant clergymen posed as if writing their sermons.[13] The Albury Banner and Wodonga Express of May 1863 finds it noteworthy that "a gentleman had occasion to advertise for a cook. Amongst other applications in answer to his advertisement was one from a "young lady" of the profession, enclosing her carte de visite and stating her salary."[14]

Demise

By the early 1870s, cartes de visite began to be supplanted by "cabinet cards", which were also usually albumen prints, but larger, and mounted on cardboard backs measuring 110 mm (4.5 in) by 170 mm (6.5 in). Nevertheless, while larger framed prints became available at photography studios, the two smaller formats were the main trade of professional portrait photographers between 1888, when George Eastman introduced the mass produced and pre-loaded Kodak which industrialised the processing and printing of amateurs' photographs,[15] and 1900, when the Brownie camera simplified the technology and so reduced the cost of the medium that snapshot photography became a mass phenomenon.

Gallery of cartes de visite

-

One of the first cartes de visite of Queen Victoria taken by photographer John Jabez Edwin Mayall

-

Tewodros II of Ethiopia in the 1860s.

-

Hector Berlioz, c.1864

-

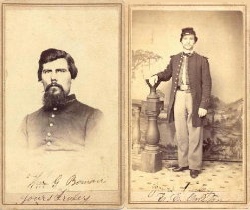

Two photographs taken during the American Civil War. Each soldier shown here served with the 77th Illinois Volunteer Infantry.

-

A later cabinet card of a similar image of Sojourner Truth.

-

One of only two known photographs of Mary Seacole, taken by Maull & Company in London, c.1873.

-

Sim D. Kehoe, who brought Indian-club exercising to the United States from England.

-

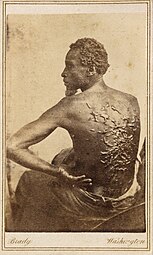

Gordon, an enslaved man, reproduced by Mathew Brady.

-

Wilson Chinn, a branded slave from Louisiana--Also exhibiting instruments of torture used to punish slaves

-

A chair presented by Kinman to Abraham Lincoln. Kinman sold CdVs in the U.S. Capitol.

-

Fridtjof Nansen, Arctic explorer and scientist 1886.

-

An early cat macro by British portrait photographer Harry Pointer, c.1870s.

-

Camille Silvy's portrait of William Fane De Salis, London, 1861.

-

A. Kerpen. Beard 8 feet long, 11 years' growth

-

Rev. Christopher Newman Hall, British clergyman c.1860

-

Elizabeth Thompson, military painter c.1875

See also

References

- ^ Also spelled carte-de-visite or erroneously referred to as carte de ville.

- ^ Welling

- ^ Leggat

- ^ Batchen, Geoffrey; Gitelman, Lisa (2019). "Afterword: Media History and History of Photography in Parallel Lines". In Leonardi, Nicoletta; Natale, Simone (eds.). Photography and other media in the nineteenth century (1st ed.). Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press. p. 197. ISBN 9780271079165. OCLC 1097575379.

- ^ Plunkett, John (2013-12-16). "Carte-de-visite". In Hannavy, John (ed.). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. Routledge. pp. 276–277. ISBN 978-0-203-94178-2.

- ^ van Monckhoven, Desirée (1859). Répertoire général de photographie pratique et théorique contenant les procédés sur plaque, sur papier, sur collodion sec et humide, sur albumine etc (in French) (3rd, avec atlas composé de dix planches ed.). Paris: A. Gaudin et frère. p. 596. OCLC 476794826.

- ^ Gernsheim p. 55

- ^ Newhall

- ^ "Fine Arts: Mr Mayall's Photographic Exhibition". Morning Herald. London. 16 August 1860. p. 6.

- ^ Sandler, Martin W. (2002). Photography: an illustrated history. USA: Oxford University Press. p. 32. ISBN 9780195126082.

- ^ "South African "Cartomania" - a photographic phenomenon | The Heritage Portal". www.theheritageportal.co.za. Retrieved 2023-05-13.

- ^ Schweitzer, Marlis, and Joanne Zerdy. 2014. Performing Objects and Theatrical Things. Houndmills, Basingstoke; New York : Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137402448.

- ^ "Davies & Co". Art Gallery of New South Wales. Retrieved 2023-05-13.

- ^ "Victorian News". Albury Banner And Wodonga Express Newspaper Archives May 23, 1863 Page 4. 23 May 1863. p. 4.

- ^ Riches, Harriet (2015). "Picture Taking and Picture Making: Gender Difference and the Historiography of Photography". In Sheehan, Tanya (ed.). Photography, history, difference. Interfaces, studies in visual culture. Hanover, New Hampshire: Dartmouth College Press,. p. 131. ISBN 9781611686463. OCLC 880122479.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

Bibliography

- Gernsheim, Helmut (1986). A Concise History of Photography. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-25128-8. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- Dr. Robert Leggat MA M.Ed Ph.D. FRPS FRSA

- Newhall, Beaumont. The history of photograph (1964)

- Silkenat, David (August 8, 2014). ""A Typical Negro": Gordon, Peter, Vincent Coyler, and the Story Behind Slavery's Most Famous Photograph" (PDF). American Nineteenth Century History. 15 (2): 169–186. doi:10.1080/14664658.2014.939807. hdl:20.500.11820/7a95a81e-909c-4e8f-ace6-82a4098c304a. S2CID 143820019.

- Welling, William. Photography in America (1978 & 1987)

External links

- Portraits of Scientists: Increase Lapham's Cartes-de-visite Collection Collected by pioneering Wisconsin antiquarian Increase A. Lapham between 1862–75, this album of carte-de-visite photographic portraits depicts many notable 19th-century scientists from America and Europe. Available on Wisconsin Historical Images, the Wisconsin Historical Society's online image database.

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections – 19th Century Actors Photographs Cartes-de-visite studio portraits of entertainers, actors, singers, comedians and theater managers who were involved with or performed on the American stage in the mid-to-late 19th century.

- William Emerson Strong Photograph Album -- Duke University Libraries Digital Collections 200 cartes de visite depicting officers in the Confederate Army and Navy, officials in the Confederate government, famous Confederate wives, and other notable figures of the Confederacy. Also included are 64 photographs attributed to Mathew Brady.

- Southern Cartes de Visite Collection, A.S. Williams III American Collection, Division of Special Collections, University of Alabama Libraries. Over 3300 digitized cartes de visite, the majority of them from southern studios.

- The Carte de Visite file at the New-York Historical Society

- Cartes de Visite of California photographers at Beinecke Library via flickr