Caesarea Philippi: Difference between revisions

Removed cat |

|||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

====Herod and Philip (20 BC – AD 34)==== |

====Herod and Philip (20 BC – AD 34)==== |

||

On the death of [[Zenodorus son of Lysanias|Zenodorus]] in 20 BC, the Panion, which included '''Paneas''', was annexed to the Kingdom of [[Herod the Great]].<ref>{{harvp|Wilson|2004|p=9}}</ref> He erected here a temple of "white marble" in honour of his patron. In the year 3 BC, [[Herod Philip II|Philip II]] (also known as Philip the Tetrarch) founded a city at Paneas. It became the administrative capital of Philip's large [[tetrarchy]] of [[Batanaea]] which encompassed the Golan and the [[Hauran]]. [[Flavius Josephus]] refers to the city as '''Caesarea Paneas''' in [[Antiquities of the Jews]]; the New Testament as '''Caesarea Philippi''' (to distinguish it from [[Caesarea Maritima]] on the [[Mediterranean]] coast).<ref>Matthew. 16:13</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Flavius|loc=''Antiquities of the Jews'' Book XVIII chapter II para 1 (p. 402)}}</ref> In 14 AD, Philip II named it Caesarea in honour of [[Roman Empire|Roman]] Emperor [[Augustus]], and "made improvements" to the city. His image was placed on a coin issued in 29/30 AD (to commemorate the founding of the city), this was considered as idolatrous by Jews but was following in the [[Edom|Idumean]] tradition of Zenodorus.<ref>{{harvp|Wilson|2004|pp=20–22}}</ref> |

On the death of [[Zenodorus son of Lysanias|Zenodorus]] in 20 BC, the Panion, which included '''Paneas''', was annexed to the Kingdom of [[Herod the Great]].<ref>{{harvp|Wilson|2004|p=9}}</ref> He erected here a temple of "white marble" in honour of his patron. In the year 3 BC, [[Herod Philip II|Philip II]] (also known as Philip the Tetrarch) founded a city at Paneas. It became the administrative capital of Philip's large [[tetrarchy]] of [[Batanaea]] which encompassed the Golan and the [[Hauran]]. [[Flavius Josephus]] refers to the city as '''Caesarea Paneas''' in [[Antiquities of the Jews]]; the New Testament as '''Caesarea Philippi''' (to distinguish it from [[Caesarea Maritima]] on the [[Mediterranean]] coast).<ref>Matthew. 16:13</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Flavius|loc=''Antiquities of the Jews'' Book XVIII chapter II para 1 (p. 402)}}</ref> In 14 AD, Philip II named it Caesarea in honour of [[Roman Empire|Roman]] Emperor [[Augustus]], and "made improvements" to the city. His image was placed on a coin issued in 29/30 AD (to commemorate the founding of the city), this was considered as idolatrous by Jews but was following in the [[Edom|Idumean]] tradition of Zenodorus.<ref>{{harvp|Wilson|2004|pp=20–22}}</ref>According to Josephus (War 3: 512-13), Philip tried to determine the source of the Jordan by throwing chaff in the nearby volcanic Lake Ram, which then appeared in Banyas. <ref>[http://www.jewishmag.co.il/34mag/banyas/banyas.htm The Banyas]</ref> |

||

====Province of Syria (AD 34–61)==== |

====Province of Syria (AD 34–61)==== |

||

Revision as of 09:32, 26 October 2021

| |

| Alternative name | Neronias |

|---|---|

| Location | Golan Heights |

| Coordinates | 33°14′46″N 35°41′36″E / 33.246111°N 35.693333°E |

| Type | settlement |

| History | |

| Cultures | Hellenistic, Roman |

Caesarea Philippi (/ˌsɛsəˈriːə fɪˈlɪpaɪ/; Latin: Caesarea Philippi, literally "Philip's Caesarea"; Ancient Greek: Καισαρεία Φιλίππεια Kaisareía Philíppeia) was an ancient Roman city located at the southwestern base of Mount Hermon. It was adjacent to a spring, grotto, and related shrines dedicated to the Greek god Pan. Now nearly uninhabited, Caesarea is an archaeological site in the Golan Heights. Caesarea was called Paneas /pəˈniːəs/ (Πανειάς Pāneiás), later Caesarea Paneas, from the Hellenistic period after its association with the god Pan, a name that mutated to Banias /ˈbɑːnjəs/, the name by which the site is known today. (This article deals with the history of Banias between the Hellenistic and early Islamic periods) For a short period, the city was also known as Neronias /nəˈroʊniəs/ (Νερωνιάς Nerōniás); the surrounding region was known as the Panion /pəˈnaɪən/ (Πάνειον Pā́neion).

Caesarea Philippi is mentioned by name in the Gospels of Matthew[1] and Mark.[2] The city may appear in the Old Testament under the name Baal Gad (literally "Master Luck", the name of a god of fortune who may later have been identified with Pan); Baal Gad is described as being "in the Valley of Lebanon below Mount Hermon."[3] Philostorgius, Theodoret, Benjamin of Tudela, and Samuel ben Samson all incorrectly identified Caesarea Philippi with Laish (i.e. Tel Dan).[4] Eusebius of Caesarea, however, accurately placed Laish in the vicinity of Paneas, but at the fourth mile on the route to Tyre.[5]

History

Hellenistic Paneas

Alexander the Great's conquests started a process of Hellenisation in Egypt and Syria that continued for 1,000 years. Paneas was first settled in the Hellenistic period. The Ptolemaic kings, in the 3rd century BC, built a cult centre.

Panias is a spring, today known as Banias, named for Pan, the Greek god of desolate places. It lies close to the "way of the sea" mentioned by Isaiah,[6] along which many armies of Antiquity marched. In the distant past a giant spring gushed from a cave in the limestone bedrock, tumbling down the valley to flow into the Hula marshes. Currently it is the source of the stream Nahal Senir. The Jordan River previously rose from the malaria-infested Hula marshes, but it now rises from this spring and two others at the base of Mount Hermon. The flow of the spring has decreased greatly in modern times.[7] The water no longer gushes from the cave, but only seeps from the bedrock below it.

Paneas was an ancient place of great sanctity and, when Hellenised religious influences were overlaid on the region, the cult of its local numen gave place to the worship of Pan, to whom the cave was dedicated and from which the copious spring rose, feeding the Huela marshes and ultimately supplying the Jordan River.[8] The pre-Hellenic deities that have been associated with the site are Ba'al-gad or Ba'al-hermon.[9]

The Battle of Panium is mentioned in extant sections of Greek historian Polybius's history of "The Rise of the Roman Empire". The battle of Panium occurred in 198 BC between the Macedonian armies of Ptolemaic Egypt and the Seleucid Greeks of Coele-Syria, led by Antiochus III.[10][11][12] Antiochus's victory cemented Seleucid control over Phoenicia, Galilee, Samaria, and Judea until the Maccabean Revolt. The Hellenised Sellucids built a pagan temple dedicated to Pan, creator of panic in the enemy, at Paneas.[13]

Roman period

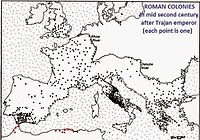

During the Roman period, the city was first part of local client kingdoms including the Herodian, then after the death of Philip the Tetrarch it was administered directly by Rome as part of Phoenicia Prima and Syria Palaestina, and finally, after AD 218, the Gaulanitis (Golan), whose capital it was, was included together with Peraea in Palaestina Secunda. The ancient kingdom of Bashan was incorporated into the province of Batanea.[14]

Herod and Philip (20 BC – AD 34)

On the death of Zenodorus in 20 BC, the Panion, which included Paneas, was annexed to the Kingdom of Herod the Great.[15] He erected here a temple of "white marble" in honour of his patron. In the year 3 BC, Philip II (also known as Philip the Tetrarch) founded a city at Paneas. It became the administrative capital of Philip's large tetrarchy of Batanaea which encompassed the Golan and the Hauran. Flavius Josephus refers to the city as Caesarea Paneas in Antiquities of the Jews; the New Testament as Caesarea Philippi (to distinguish it from Caesarea Maritima on the Mediterranean coast).[16][17] In 14 AD, Philip II named it Caesarea in honour of Roman Emperor Augustus, and "made improvements" to the city. His image was placed on a coin issued in 29/30 AD (to commemorate the founding of the city), this was considered as idolatrous by Jews but was following in the Idumean tradition of Zenodorus.[18]According to Josephus (War 3: 512-13), Philip tried to determine the source of the Jordan by throwing chaff in the nearby volcanic Lake Ram, which then appeared in Banyas. [19]

Province of Syria (AD 34–61)

On the death of Philip II in AD 34, the tetrarchy was incorporated into the province of Syria with the city given the autonomy to administer its own revenues.[20]

Neronias (AD 61–68)

In 61 AD, King Agrippa II renamed the administrative capital Neronias in honour of Roman Emperor Nero: "Neronias Irenopolis" was the full name.[21] But this name held only until 68 AD when Nero committed suicide.[22] Agrippa also carried out urban improvements[23] It is possible that Neronias received "colonial status" by Nero, who created some colonies[24]

During the First Jewish–Roman War, Vespasian rested his troops at Caesarea Philippi in July 67 AD, holding games over a period of 20 days before advancing on Tiberias to crush the Jewish resistance in Galilee.[25]

Gospel association

In the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus is said to have approached the area near the city, but without entering the city itself. Jesus, while in this area, asked his closest disciples who they thought he was. Accounts of their answers, including the Confession of Peter, are found in the Synoptic Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Here Saint Peter made his confession of Jesus as the Messiah and the "Son of the living God", and Christ in turn gave a charge to Peter. The apostles Peter, James and John were eyewitnesses to the Transfiguration of Christ, which happened "in a high place nearby" and is recorded in Matthew (17:1-7), Mark (9:2-8) and Luke (9:28-36).[26]

According to the Christian ecclesiastical tradition, a woman from Paneas, who had been bleeding for 12 years, was miraculously cured by Jesus.[27]

Byzantine period

On attaining the position of Emperor of the Roman Empire in 361 AD Julian the Apostate instigated a religious reformation of the Roman state, as part of a programme intended to restore the lost grandeur and strength of the Roman state.[28] He supported the restoration of Hellenic paganism as the state religion.[29] In Paneas this was achieved by replacing the Christian symbols. Sozomen describes the events surrounding the replacement of a statue of Christ (which was also seen and reported by Eusebius):-

Having heard that at Caesarea Philippi, otherwise called Panease Paneades,[dubious ] a city of Phoenicia, there was a celebrated statue of Christ, which had been erected by a woman whom the Lord had cured of a flow of blood. Julian commanded it to be taken down, and a statue of himself erected in its place; but a violent fire from the heaven fell upon it, and broke off the parts contiguous to the breast; the head and neck were thrown prostrate, and it was transfixed to the ground with the face downwards at the point where the fracture of the bust was; and it has stood in that fashion from that day until now, full of the rust of the lightning."[30]

Early Islamic period

In 635, Paneas gained favourable terms of surrender from the Muslim army of Khalid ibn al-Walid, after the defeat of Heraclius's army. In 636 AD, a newly formed Byzantine army advanced on Palestine, using Paneas as a staging post, on the way to confront the Muslim army at Yarmuk.[31]

The depopulation of Paneas after the Muslim conquest was rapid, as the traditional markets of Paneas disappeared (only 14 of the 173 Byzantine sites in the area show signs of habitation from this period). The Hellenised city fell into decline. The council of al-Jabiyah established the administration of the new territory of the Umar Caliphate, and Paneas remained the principal city of the district of al-Djawlan (the Golan) within Jund Dimashq, jund meaning "military province" and Dimashq being the Arabic name of Damascus, due to its strategic military importance on the border with Filistin (Palestine).[32]

Around 780, the nun Hugeburc visited Caesarea and reported that the town had a church and a "great many Christians".[33]

Bishopric (Byzantine period until present)

Caesarea Philippi became the seat of a bishop at an early date: local tradition has it that the first bishop was the Erastus mentioned in Saint Paul's Letter to the Romans (Romans 16:23). What is historically verifiable is that the see's bishop Philocalus was at the First Council of Nicaea (325), that Martyrius was burned to death under Julian the Apostate, that Baratus was at the First Council of Constantinople in 381. Flavian, (420) Bishop of Caesarea Philippi[34][35][36][37] and Olympius at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD. In addition there is mention of a Bishop Anastasius of the same see, who became Patriarch of Jerusalem in the 7th century.

In the time of the Crusades, Caesarea Philippi became a Latin Church Suffragan diocese, under the Metropolitan See of Tyre, and the names of two of its bishops, Adam and John, are known.[38][39][40][41] No longer a residential bishopric, Caesarea Philippi is today listed by the Roman Catholic Church as a titular see.[42] It is also one of the sees to which the Antiochian patriarchate of the Orthodox Church has appointed a titular bishop.

Archaeology

Today Caesarea Philippi is a site of archeological importance, and lies within the Hermon Stream Nature Reserve.[43] The ruins are extensive and have been thoroughly excavated. Within the city area the remains of Agrippa's palace, the cardo, a bath-house and a Byzantine-period synagogue.[44]

A Byzantine church dated circa 400 CE was discovered on top of a Roman-era temple to Pan, adapted to fit the needs of Christian worshippers. It is thought to have been built to commemorate Jesus’s interactions with Peter. [45]

See also

- List of places associated with Jesus

- Roman Palestine

- Caesarea Maritima (modern Caesarea), in Israel

- Caesarea Mazaca (modern Kayseri) in Turkey

- Baniyas in northwestern Syria

References

- ^ Matthew 16:13–20

- ^ Mark 8:27–30

- ^ Joshua 11:17, 12:7, and 13:5.

- ^ Provan, Long & Longman 2003, pp. 181–183; Wilson (2004), p. 150; de Saulcy & de Warren (1854), pp. 417–418

- ^ de Saulcy & de Warren (1854), p. 418

- ^ Isaiah 9:1

- ^ Wilson (2004), p. 2

- ^ Kent (2007), pp. 47–48

- ^ Bromiley (1995), p. 569

- ^ Perseus Digital Library. TUFTS University Polybius Book 16 para 18

- ^ Perseus Digital Library. TUFTS University Polybius Book 16 para 19

- ^ Perseus Digital Library. TUFTS University Polybius Book 16 para 20

- ^ Chambers Dictionary of Etymology: The Origins and Development of Over 25,000 English Words Edited By Robert K. Barnhart, Sol Steinmetz (1999) Chambers Harrap Publishers L, ISBN 0-550-14230-4, p 752

- ^ "The Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal". google.com.

- ^ Wilson (2004), p. 9

- ^ Matthew. 16:13

- ^ Flavius, Antiquities of the Jews Book XVIII chapter II para 1 (p. 402)

- ^ Wilson (2004), pp. 20–22

- ^ The Banyas

- ^ Wilson (2004), p. 23

- ^ Neronias Irenopolis

- ^ Madden, Frederic William (1864) History of Jewish Coinage, and of Money in the Old and New Testament B. Quaritch, p 114

- ^ "As for Panium itself, its natural beauty had been improved by the royal liberality of Agrippa, and adorned at his expenses" (Flavius, War of the Jews, Book III, chapter X, para 7 (p. 584)).

- ^ Caesarea Philippi under Nero was called "Neronias" (in Spanish)

- ^ Emil Schürer, Fergus Millar, Géza Vermès (1973) The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ (175 BC-AD 135) Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 0-567-02242-0 p 494

- ^ Matthew 17:1-7, Mark 9:2-8; Luke 9:28-36

- ^ Luke; 8:43; Mark 5:23; Matthew 9:20

- ^ Norwich (1988), pp. 88–92

- ^ Brown (1971), p. 93

- ^ Wilson (2004), p. 99

- ^ Wilson (2004), p. 114

- ^ Wilson (2004), pp. 115–116

- ^ Wilson (2004), pp. 118–119

- ^ Richard Price, Michael Gaddis, The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon, Volume 1 (Liverpool University press, 2005)p301.

- ^ Karl Joseph von Hefele, A History of the Councils of the Church: To the close of the Council of Nicea, A.D. 325 (T. & T. Clark, 1871)p35.

- ^ Letters 1–50 (The Fathers of the Church, Volume 76) (CUA Press, 1 Apr. 2007)p70.

- ^ Karl Joseph von Hefele, A History of the Councils of the Church: To the close of the Council of Nicea, A.D. 325 (T. & T. Clark, 1871) p35.

- ^ Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae, Leipzig 1931, p. 434

- ^ Michel Lequien, Oriens christianus in quatuor Patriarchatus digestus, Paris 1740, Vol. II, coll. 831-832

- ^ Konrad Eubel, Hierarchia Catholica Medii Aevi, vol. 1, p. 387; vol. 5, p. 305; vol. 6, p. 326

- ^ Raymond Janin, v. Césarée de Philippe, in Dictionnaire d'Histoire et de Géographie ecclésiastiques, vol. XII, Paris 1953, coll. 209-211

- ^ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 867

- ^ Hermon Stream (Banias) Nature Reserve Archived 2014-10-18 at the Wayback Machine at INPA website

- ^ article at biblewalks.com

- ^ Rare early Christian church built atop Temple to Pan found in northern Israel

Bibliography

- Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (1995). International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: A–D. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0-8028-3781-6.

- Brown, Peter (1971). The World of Late Antiquity. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-95803-5.

- de Saulcy, Louis Félicien Joseph Caignart; de Warren, Édouard (1854). Narrative of a Journey Round the Dead Sea, and in the Bible Lands; in 1850 and 1851. Including an Account of the Discovery of the Sites of Sodom and Gomorrah. Parry and M'Millan.

- Flavius, Josephus. The works of Flavius Josephus: in three volumes; with illustrations by Josephus Flavius. Vol. 1. Translated by Whiston, William. London & New York: George Routledge & Sons. pp. 402584.

- Kent, Charles Foster (2007) [1912]. Biblical Geography and History. Read Books. ISBN 1-4067-5473-0.

- Norwich, John Julius (1988). Byzantium; the Early Centuries. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-011447-5.

- Provan, Iain William; Long, V. Philips; Longman, Tremper (2003). A Biblical History of Israel. London: Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 181–183. ISBN 0-664-22090-8.

- Wilson, John Francis (2004). Caesarea Philippi: Banias, the Lost City of Pan. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 1-85043-440-9.

Further reading

- al-Athīr, ʻIzz al-Dīn Ibn (translated 2006). The Chronicle of Ibn Al-Athīr for the Crusading Period from Al-Kāmil Fīʼl-taʼrīkh: The Years AH 491-541/1097-1146, the Coming of the Franks And the Muslim Response Translated by Donald Sidney Richards, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 0-7546-4078-7

- Fitzmyer, Joseph A. (1991). A Christological Catechism: New Testament Answers. Paulist Press, ISBN 0-8091-3253-2

- Gregorian, Vartan (2003). Islam: A Mosaic, Not a Monolith. Brookings Institution Press, ISBN 0-8157-3283-X

- Hindley, Geoffrey (2004). The Crusades: Islam and Christianity in the Struggle for World Supremacy. Carroll & Graf Publishers, ISBN 0-7867-1344-5

- Josephus Flavius (1984). Betty Radice; E. Mary Smallwood (eds.). The Jewish War. Translated by G. A. Williamson (Revised ed.). Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044420-3.

- Murphy-O'Connor, Jerome (2008). The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700. Oxford University Press US, ISBN 0-19-923666-6

- Polybius (1979). The Rise of the Roman Empire. Translated by Ian Scott-Kilvert; Introduction by Frank William Walbank. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044362-2.

- Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades, c. 1071—-c. 1291. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-62566-1

- Salibi, Kamal Suleiman (1977). Syria Under Islam: Empire on Trial, 634-1097. Caravan Books, ISBN 0-88206-013-9

External links

- Hermon Stream (Banias) Nature Reserve , aka Banias National Park, at the Israel Nature and Parks Authority homepage. Accessed Oct 2021.

- article at jewishmagazine.co.il (retrieved 14.10.2014)

- Hellenistic sites in Syria

- Archaeological sites in Quneitra Governorate

- Classical sites on the Golan Heights

- Coele-Syria

- Crusade places

- Former populated places on the Golan Heights

- Holy cities

- Medieval sites on the Golan Heights

- New Testament cities

- Pan cult sites

- Populated places of the Byzantine Empire

- Ptolemaic Kingdom

- Roman sites in Syria

- Seleucid Empire

- Catholic titular sees in Asia