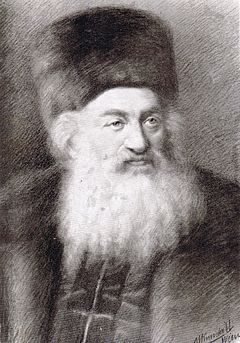

Shimon Sofer

Shimon Sofer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 18, 1820 (13 Tevet 5581 Anno Mundi) |

| Died | March 26, 1883 (aged 62) (17 Adar II 5643 Anno Mundi) |

| Resting place | Kraków, Poland |

| Other names | Rabbi Simon Schreiber, the Michtav Sofer |

| Occupation | Chief Rabbi |

| Spouse | Miriam Sternberg |

| Children | Akiva, Yisrael David Simcha (Bunim), Yoel, Shlomo Aleksandri, Asher, Raizel (Kornitzer), Shulamit (Roth) |

| Parent(s) | Moshe and Sarel Sofer (Schreiber) |

| Relatives | Avraham Shmuel Binyamin Sofer (brother) |

Shimon Sofer (German: Simon Schreiber; 1820–1883) was a prominent Austrian Orthodox Jewish rabbi in the 19th century. He was Chief Rabbi of Kraków, Poland after serving as Chief Rabbi of Mattersdorf. He was the second son of Rabbi Moshe Sofer (Chassam Sofer) of Pressburg.

As president of the Orthodox Jewish party Machzikei HaDas, Sofer was a member of the Polenklub at the Reichsrat under the Austria-Hungary monarch Franz Joseph I. He was elected as Deputy of the Kolomyia's election district of Galicia.

He became the foremost leader of the Orthodox Jews of Galicia in religious as well as in worldly matters.[1] As a Halakhist and Talmudist he authored commentary and responsa in a work known today as Michtav Sofer.[2]

Early life

[edit]Rabbi Shimon Sofer was born 13 Tevet 5581 (December 18, (1820)[citation needed] in the city of Pressburg, Kingdom of Hungary (now Bratislava, Slovakia), where his father, Rabbi Moses Schreiber (1762-1839), was serving as chief rabbi. His mother, Sarah-Sorele Schreiber (1790–1832), was the daughter of Rabbi Akiva Eger, the rabbi of Poznań, and the sister of Rabbi Abraham Moses Kalischer (1788–1812), the rabbi of Piła. She had ten other children beside him, and he lost her when he was eleven years old. He was named Shimon after his ancestor, the author of Yalkut Shimoni.

Shimon was recognized as a child prodigy at a very early age. His father would seat him on his lap whilst delivering his weekly Chumash shiur at the Pressburg Yeshiva, where he expounded on Rashi and Ramban commentaries.

At the age of 9, he was fluent in the works of the Shlah HaKadosh and the Baal HaAkeida. He displayed great interest in Jewish Poetry, a talent which is noticeable in his later Torah works. His favorite piyyut was Ya Ribon of Rabbi Israel ben Moses Najara, a Shabbat song which his father would not sing.

His father would affectionately call him Shimon Chassida (the pious), and at the age of 13, at his Bar Mitzva, ordained him with the Ashkenazi title “Chaver”.

Shimon matured quickly and at the age of 17[3][4] he married Miriam Sternberg, a daughter of philanthropist Rabbi Dov Ber Sternberg (Reb Ber Sighet) of Carei (also known as Nagykároly).

After his marriage, he moved back to Pressburg, and upon instruction from his father, started learning Kaballa with Pressburg Dayan Rabbi Natan Binyamin Lieber (1805–1880) (Yiddish: נטע וואלף סג"ל)[3] author of Sheeris Natan Binyamin.

Shimon was a mere 19 years old when his father died. His brother Avraham Shmuel Binyamin, 6 years his elder, was appointed as Chief Rabbi of Pressburg.

Avraham Shmuel Binyamin and Shimon continued to edit and publish their father's Torah commentary and Halakhic rulings, a project placed upon them by their father during his lifetime. During this time they completed the first volume of Chassam Sofer Responsa on Yoreh De'ah (שו"ת חת"ס חיו"ד).

Rabbinical positions

[edit]Circa 1841 (5602), he moved to Nagykaroly, to be with his father-in-law.

Circa 1843 (5603) he became rabbi of Mattersdorf, a position his father filled some 40 years earlier. There he founded a yeshiva and became involved in communal and national matters. He remained steadfast in his father's way of refusing to accept any reform or change to traditional orthodox Judaism.

Circa 1849 (5610) he was offered a Chief Rabbinical position in Yarmat, which for an unknown reason, he turned down.

Circa 1851 (5612), the Jewish community in Nikolsberg invited Sofer to accept the Chief Rabbinical position of their city. Rabbi Shimon again turned down this offer reasoning that he could not possibly stand in the position of previous "Torah giants" (such as the Mahara”l, Tosefes Yom Tov, Rabbi Shmuel Shmelke Horowitz and Rabbi Mordechai Benet who had served there as Chief Rabbi).

Circa 1855 (5616), the Jewish Community of Pápa offered him to serve as Chief Rabbi of their city, an offer he refused. He reasoned that this community had removed their bima from the center of their Synagogue and moved the Chazzan's position to the face the congregation from a high stage. This, in his opinion was an unacceptable change to tradition and against halakha. Although the community promised to relocate the bima and amud in accordance to tradition, Rabbi Shimon still refused. In a letter written to his brother-in-law and sister Rabbi Shlomo & Gitel Spitzer, he explained that he and his wife planned on moving to Jerusalem in the Land of Israel and a five-year contract with this community would restrict him on this plan.

Circa 1857 (5618), the Jewish Community of Kraków offered Sofer the position of Chief Rabbi, an offer that Sofer took seriously but deliberated for some time.

Circa 1859 (5620) Rabbi Sofer accepted this position and moved to Kraków. Amongst those who convinced him to accept this post was Rabbi Chaim Halberstam, Rebbe of Sanz. His position of Chief Rabbi of Mattersdorf was filled by his nephew Rabbi Shmuel Ehrenfeld (1835–1883) author of Chassan Sofer.

In Kraków

[edit]Kraków was the home to a thriving Orthodox Jewish Community. Jewish presence there has been recorded as early as the 12th century. Since the 16th century many "Torah giants" served there as Chief Rabbi, such as the Rem”a, Ba”ch, Tosfos Yom Tov and the Maginei Shlomo.[5]

During Rabbi Sofer's rabbinate, Jews in Kraków numbered between 15,000 and 20,000 adults over the age of 15. In one of his letters written in 1879, Sofer states that there were over 80 minyanim in Kraków alone.[6][7]

At this time, the Haskalah movement had made an impression on the general Jewish Population of the Austria-Hungarian empire with many Jews assimilating or rejecting the traditional orthodox approach to Judaism.

The Jews enjoyed freedom and rights under the rule of the Emperor Franz Joseph I who sympathized with them. Franz Joseph had even made a visit to Jerusalem in 1869 where he was welcomed warmly by the Orthodox Jewish community and leaders. He had donated the dome on the Tiferes Yisrael Synagogue in Jerusalem.[8]

The Hasidim and the Austrian-Hungarian rabbis of the Sofer Dynasty made a joint effort to strengthen traditional Orthodox Judaism and opposed the Reform both socially and politically.

A major challenge for the traditional Orthodox Jews was opposing the Shomer Israel Society, a strong and influential reform group. Shomer Israel supported assimilation of Jews with the general population and sought legislation forcing Yeshiva's to study philosophy and secular studies, something which the Orthodox staunchly opposed. In 1880, Rabbi Shimon Sofer founded a Hebrew-Yiddish weekly newspaper named מחזיקי הדת (Machzikei Hadas or Maḥaziḳe ha-Dat; Zeitung fur das Wahre Orthodoxische Judentum), published in Lemberg,[1] to counter the Izraelit tabloid issued by Shomer Israel.

In 1878 (5638), Rabbi Sofer and the Rebbe of Belz, Rabbi Yehoshua Rokeach, founded a political party naming it Machzikei Hadas. This party was supported by all the traditional orthodox communities of Galicia. Galician Jewry numbered some 800,000 persons at this time. The organization received recognition from the Austrian Kultusministerium (Ministry of Culture). It could be considered the first attempt of the Orthodox Jews in Europe to unite for political action in order to foster its beliefs in the sphere of Jewish social life.

In 1878, Machzikei Hadas aligned itself with the Polish Club Polenklub and presented Rabbi Sofer as its candidate for the electorate of the Galician districts of Kolomyia, Sniatyn and Buchach which had large Jewish electorates.[9] In 1879,[1][9] Sofer was elected and earned a seat at the Reichsrat (Austrian Parliament). Though Sofer was a talented orator and pretty fluent in the German language, the official language at the Reichsrat was Polish. It has been recorded that probably due to this Sofer did not speak at any assembly[9] rather used his political influence off stage.

Joseph Margoshes (1866–1955), a writer for the New York Yiddish daily Morgen Journal,[10] describes Sofer in his memoir A World Apart:

The Krakow Rabbi was an unusually attractive person with a handsome face and rosy cheeks. He carried himself like a true aristocrat and did not like to get excited.[9]

Although presiding over the Machzikei Hadas brought Sofer and the Orthodox Community honor and satisfaction, he endured much disrespect and personal insults from the Shomer Israel Society and newspapers such as the Izraelit and HaIvri whose editorials carried personal insults to him and his colleagues.[9]

Rabbi Sofer and Franz Joseph I

[edit]

Emperor of Austria; Apostolic King of Hungary; King of Bohemia; King of Croatia; King of Galicia and Lodomeria; Grand Duke of Kraków

In 1880 (כ"ה אלול תר"ם), The Emperor of the Austria-Hungarian Empire Franz Joseph I made a 3-day visit to Kraków. Amongst the general population who greeted the Emperor at the train station, was the Orthodox Jewish community headed by Rabbi Shimon Sofer and his son-in-law, Rabbi Akiva Kornitzer.

In a letter written the next morning (יום ה' ה' דסליחות תר"ם) to his son and daughter-in-law, Rabbi Shlomo and Hinda Sofer, he writes with great awe of his encounter with the emperor:

The Jewish delegation awaited the emperor in a line under chuppa canopies with the leaders holding Torah scrolls adored with gold and silver accessories. His Excellency Franz Joseph sat in a carriage together with Prince Albrecht. Upon passing the Jewish delegation, he acknowledged the Torah scrolls by rising and bowing down at their sight. The Emperor continued to his lodging prepared by Potocki (probably; Alfred Józef Potocki). Rabbi Sofer and twelve delegates of the Jewish community formally welcomed the Emperor at the lodging. Rabbi Sofer requested the emperor's permission to don his hat in order to bless the Emperor, which was granted cordially. Rabbi Sofer made the traditional blessing (שנתן מכבודו) to which the Emperor answered "Amen". Sofer described the welcoming as "splendid", writing that he was invited to the "ball" that evening but was not planning on attending.

The Machzikei HaDas newspaper of 19 September 1880 carried a front-page report heralding the Emperor's visit to Kraków and Lwóv, comparing him to an "Angel sent by God". Articles bestowed Franz Joseph with titles such as "our father, our king, the almighty, righteous and merciful". The report describes the joy and happiness of the Jewish community and the respect they and Rabbi Sofer received from the Emperor, an unprecedented event in Diaspora Jewish history.[11]

On 10 May 1881, Rabbi Sofer sent a parchment scroll to the Emperor Franz Joseph on the occasion of the wedding of his son Rudolf. The scroll, containing blessings and good wishes, was decorated with pure gold. It was written on behalf of the Orthodox Jewish community in Galicia and signed by Rabbi Sofer (signed; Simon Schreiber). It was received with gratitude.[12]

One line of the Lamentation Eulogy which was authored after Rabbi Shimon's death by his son Rabbi Yisrael David Simcha (Bunim) Sofer and printed in Machzikei Hadas newspaper reads: שמח מלכו עמו ובאות נתכבד (Happy was the King with him, and with an award was dignified). In a footnote he explains this passage:

In the outbreak of the war between “Österreich“ and “Ashkenaz“ (Austro-Prussian War) in the year [5]626 (1866), many hundreds of wounded were sent to the city of Kraków for treatment. My honorable father and teacher of blessed memory made great effort to supervise over them with an eye of compassion, to fulfill their needs and to fund their cure. In return for his faithful work, His Excellency The Kaiser (Emperor Franz Joseph I) decorated him an Honorary Medal as an everlasting sign of appreciation.[13]

Death of his brother Avraham Shmuel Binyamin

[edit]Rabbi Shimon was not informed of the death of his brother Avraham Shmuel Binyamin on December 31, 1871 and did not take part in his burial. Rabbi Azriel Hildesheimer, who took part and recorded a memoir of the burial, mentions that the Kraków community withheld three telegrams sent by the Pressburg community and family from reaching him. Hildersheimer writes that the Kraków community feared that the Pressburg community would appoint him as their Chief Rabbi.[14]

In a condolence letter written to his brother's family two weeks after the passing, Rabbi Shimon apologizes for not responding to the telegrams sent. He wrote that his family and community withheld the news from him and that the death of his brother came to his knowledge by chance. He discovered the news upon seeing his son-in-law reading the laws of Avelut.[14]

Death of Rabbi Shimon

[edit]On Purim 1883 (5643), Rabbi Sofer celebrated with his congregation as usual, festivities continued into the late hours of the night.

On the eve of 17 Adar II, 1883 (5643), he started to feel unwell. The next morning doctors examined him and prescribed medicine. He prayed with Tallit and Tefillin until 10:00am.[citation needed] Therefater he sent for his son-in-law, Rabbi Akiva Kornitzer, and said to him,

Understand, my son, that for many years my eyes and heart have been constantly turned toward the Holy Land. However, for fear that I be accused for neglecting the tasks that I was responsible for, I never said anything. And now, the time has come to visit the Holy Land.

These were his last words before he died.

His son-in-law, Rabbi Akiva Kornitzer succeeded him as Chief Rabbi of Kraków.[15]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "SCHREIBER, SIMON". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "SCHREIBER, SIMON". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

Jewish Encyclopedia bibliography:

S. Schreiber, Ḥut ha-Meshullash, p. 66b;

Friedberg, Luḥot Zikkaron, p. 37, at Google Books. - ^ Joseph, Marie (31 January 2013). מכתב סופר. Jerusalem. ISBN 9781448183036. OCLC 233311895. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b His nephew, S. Schreiber. חוט המשולש (in Hebrew). Retrieved 2013-11-11.

- ^ מליצי אש (in Hebrew). Retrieved 2013-11-11.

- ^ "Rabbis of Krakow". Kehilalinks.jewishgen.org. Retrieved 2012-01-25.

- ^ "Jewish Population in Krakow". Ics.uci.edu. 2001-03-29. Retrieved 2012-01-25.

- ^ "משפחה - דרשת רבי שמעון סופר בקרקא". Kipa.co.il. 2002-12-25. Retrieved 2012-01-25.

- ^ "Synagogues of the World - Jerusalem". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2012-01-25.

- ^ a b c d e Joseph Margoshes (2008). "7". A World Apart: A Memoir of Jewish Life in Nineteenth Century Galicia. Brighton, MA: Academic Studies Press. ISBN 978-1-934843-10-9. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- ^ A World Apart: A Memoir of Jewish Life in Nineteenth Century Galicia at Google Books

- ^ "מחזיקי הדת Vol. 3 No. 2". Lemberg: Hebrewbooks.org. 19 September 1880. p. 1. Retrieved 2012-01-25.

- ^ Igrot Michtav Sofer 2006

- ^ Yisrael David Simcha (Bunim) Sofer. "Beilage zu Machzike Hadas Nr. 3" (in Hebrew). Hebrewbooks.org. p. 2. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

- ^ a b מ. א. ז. קינסטליכער; יצחק ישעיה ווייס, eds. (c. 1989). "צפונות No. 6". Hebrewbooks.org. p. 64. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

- ^ Yisrael David Simcha (Bunim) Sofer. "Beilage zu Machzike Hadas Nr. 3" (in Hebrew). p. 3. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

External links

[edit]- 1820 births

- 1883 deaths

- 19th-century Polish rabbis

- Austrian Orthodox rabbis

- Austrian newspaper people

- Rabbis from Austria-Hungary

- Chief rabbis of cities

- 19th-century newspaper founders

- Rabbis from Bratislava

- 19th-century Austrian journalists

- Austrian male journalists

- 19th-century Austrian male writers

- Rabbis from Kraków