Shortening

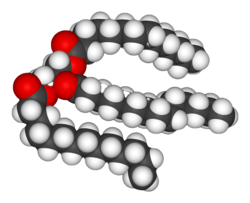

Shortening is any fat that is a solid at room temperature and is used to make crumbly pastry and other food products.

The idea of shortening dates back to at least the 18th century, well before the invention of modern, shelf-stable vegetable shortening.[1] In the earlier centuries, lard was the primary ingredient used to shorten dough.[2] The reason it is called shortening is that it makes the resulting food crumbly, or to behave as if it had short fibers. Solid fat prevents cross-linking between gluten molecules. This cross-linking would give dough elasticity, so it could be stretched into longer pieces.[2] In pastries such as cake, which should not be elastic, shortening is used to produce the desired texture.[1][2]

History and market

[edit]

Originally shortening was synonymous with lard, but with the invention of margarine from beef tallow by French chemist Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès in 1869, margarine also came to be included in the term. Since the invention of hydrogenated vegetable oil in the early 20th century, "shortening" has come almost exclusively to mean hydrogenated vegetable oil. Modern margarine is made mainly of refined seed oil and water, and may also contain milk. Vegetable shortening shares many properties with lard: both are semi-solid fats with a higher smoke point than butter and margarine. They contain less water and are thus less prone to splattering, making them safer for frying. Lard and shortening have a higher fat content compared to about 80% for butter and margarine. Cake margarines and shortenings tend to contain a few percent of monoglycerides whereas other margarines typically have less. Such "high ratio shortenings" blend better with hydrophilic ingredients such as starches and sugar.[3]

Hydrogenation of organic substances was first developed by the French chemist Paul Sabatier in 1897, and in 1901 the German chemist Wilhelm Normann developed the hydrogenation of fats, which he patented in 1902.[4] In 1907, a German chemist, Edwin Cuno Kayser, moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, the home town of soap manufacturer Procter & Gamble. He had worked for British soap manufacturer Joseph Crosfield and Sons and was well acquainted with Normann's process, as Crosfield and Sons owned the British rights to Normann's patent.[4] Soon after arriving, Kayser made a business deal with Procter & Gamble, and presented the company with two processes to hydrogenate cottonseed oil, with the intent of creating a raw material for soap.[4] Another inventor by the name of Wallace McCaw in Macon, Georgia also played a role in the invention of shortening. In 1905 McCaw patented a process in which he could turn inexpensive and commercially useless cottonseeds into imitation lard and soap.[5] Later in 1909, Procter & Gamble hired McCaw and purchased his patents along with the patents of other scientists working on partial hydrogenation which later helped in the development of "shortening".[6] Since the product looked like lard, Procter & Gamble instead began selling it as a vegetable fat for cooking purposes in June 1911, calling it "Crisco", a modification of the phrase "crystallized cottonseed oil".[4]

While similar to lard, vegetable shortening was much cheaper to produce. Shortening also required no refrigeration, which further lowered its costs and increased its appeal in a time when refrigerators were rare. Shortening was also more neutral in flavor than butter and lard which gave it a unique advantage when cooking.[7] With these advantages, plus an intensive advertisement campaign by Procter & Gamble, Crisco quickly gained popularity in American households.[4] The company targeted mothers by presenting shortening as a more economical and cleaner way of preparing meals. Procter & Gamble played into the neutral flavor of shortening as well as the high smoke point. As a result, they claimed that the natural flavors of the meal would shine through and be free of black particles and unruly smells common with other fats.[8] Procter & Gamble also advertised how economical it was to use shortening, often advertising cheap recipes incorporating shortening to appeal to frugal mothers.[9] As food production became increasingly industrialized and manufacturers sought low-cost raw materials, the use of vegetable shortening also became common in the food industry. In addition, vast US government-financed surpluses of cottonseed oil, corn oil, and soybeans also helped create a market in low-cost vegetable shortening.[10]

Crisco, owned by The J.M. Smucker Company since 2002, remains the best-known brand of shortening in the US, nowadays consisting of a blend of partially and fully hydrogenated soybean and palm oils.[11] In Ireland and the UK, Trex is a popular brand[citation needed], while in Australia, Copha is popular, made primarily from coconut oil.

Shortened dough

[edit]A short dough is one that is crumbly[2] or mealy. The opposite of a short dough is a "long" dough, one that stretches.[2]

Vegetable shortening (or butter, or other solid fats) can produce both types of dough; the difference is in technique. To produce a short dough, which is commonly used for tarts, the shortening is cut into the flour with a food processor, a pastry blender, a pair of table knives, fingers, or other utensil until the resulting mixture has a fine, cornmeal-like texture. For a long dough, the shortening is cut in only until the pea-sized crumbs are formed, or even larger lumps may be included. After cutting in the fat, the liquid (if any) is added and the dough is shaped for baking.

Neither short dough nor long flake dough are considered to be creamed or stirred batters.

Health concerns and reformulation

[edit]In the early 21st century, vegetable shortening became the subject of some health concerns due to its traditional formulation from partially hydrogenated vegetable oils that contain trans fat, a type not found in significant amounts in any naturally occurring food, that have been linked to a number of adverse health effects.[12][13][14][15][16] Consequently, a low trans fat variant of US brand Crisco was introduced in 2004. In January 2007, all Crisco products were reformulated to contain less than one gram of trans fat per serving, and the separately marketed trans-fat-free version introduced in 2004 was consequently discontinued.[17] In 2018, the FDA issued a ban on partially hydrogenated oils, forcing Procter & Gamble to reformulate their shortening.[18] As of October 2024 Crisco contains fully hydrogenated palm oil instead of partially hydrogenated vegetable oil in order to comply with FDA regulations.[19] However, fully hydrogenated oils are hard and waxy which has resulted in Crisco mixing their shortening with soybean oils as well as more palm oil.[19] As a result, the new Crisco formula which is heavily dependent upon palm oil is controversial due to the environmental impact of palm oil on rainforests as large areas of rainforest must be cleared.[20] In 2006, UK brand Cookeen was also reformulated to remove trans fats.[10]

Instead of using fully hydrogenated oils to replace partially hydrogenated oils in food, a possible alternative could be the use of plant sterols, as highlighted by the work of Prof J Ralph Blanchfield. His research in food science indicates that plant sterols could be used in products like shortening to lower the risk of coronary heart disease by inhibiting the absorption of cholesterol in the small intestine.[21]

| Type of fat | Total fat (g) | Saturated fat (g) | Monounsaturated fat (g) | Polyunsaturated fat (g) | Smoke point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butter[22] | 81 | 51 | 21 | 3 | 150 °C (302 °F)[23] |

| Canola oil[24] | 100 | 6–7 | 62–64 | 24–26 | 205 °C (401 °F)[25][26] |

| Coconut oil[27] | 99 | 83 | 6 | 2 | 177 °C (351 °F) |

| Corn oil[28] | 100 | 13–14 | 27–29 | 52–54 | 230 °C (446 °F)[23] |

| Lard[29] | 100 | 39 | 45 | 11 | 190 °C (374 °F)[23] |

| Peanut oil[30] | 100 | 16 | 57 | 20 | 225 °C (437 °F)[23] |

| Olive oil[31] | 100 | 13–19 | 59–74 | 6–16 | 190 °C (374 °F)[23] |

| Rice bran oil | 100 | 25 | 38 | 37 | 250 °C (482 °F)[32] |

| Soybean oil[33] | 100 | 15 | 22 | 57–58 | 257 °C (495 °F)[23] |

| Suet[34] | 94 | 52 | 32 | 3 | 200 °C (392 °F) |

| Ghee[35] | 99 | 62 | 29 | 4 | 204 °C (399 °F) |

| Sunflower oil[36] | 100 | 10 | 20 | 66 | 225 °C (437 °F)[23] |

| Sunflower oil (high oleic) | 100 | 12 | 84[25] | 4[25] | |

| Vegetable shortening [37] | 100 | 25 | 41 | 28 | 165 °C (329 °F)[23] |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Harper, Douglas. "shortening". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ a b c d e Moncel, Bethany (31 July 2020). "Learn About Each Variety of Shortening to Use in Baking". The Spruce Eats. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ Ian P. Freeman, "Margarines and Shortenings" Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2005, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim doi:10.1002/14356007.a16_145

- ^ a b c d e Jackson & List (2007). "Giants of the Past: The Battle Over Hydrogenation (1903–1920)", Inform 18.

- ^ "Annual report of the Commissioner of Patents for the year 1905". library.si.edu.

- ^ Massee, Jordon (4 February 2024). Accepted Fables. Indigo Custom. ISBN 9780976287551.

- ^ Oliver, Lynne. "Shortening and Cooking Oils".

- ^ "1919 Ad Crisco Woman Cooking Shortening Frying Lard - ORIGINAL ADVERTISING SEP4". Period Paper. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ Gressle, Lesley. "933 Crisco Vintage Ad, Advertising Art, Magazine Ad, 1930's Dinner, Advertisement, 1930's Recipes, Great for Framing". Etsy. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ a b The Guardian: Grease is the Word, Guardian Unlimited, 27 September 2006

- ^ "Products - Shortening - All-Vegetable Shortening - Crisco". Crisco.com. 30 September 2010. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- ^ Valenzuela A, Morgado N (1999). "Trans fatty acid isomers in human health and in the food industry". Biological Research. 32 (4): 273–87. doi:10.4067/s0716-97601999000400007. PMID 10983247.

- ^ Kummerow FA, Zhou Q, Mahfouz MM, Smiricky MR, Grieshop CM, Schaeffer DJ (April 2004). "Trans fatty acids in hydrogenated fat inhibited the synthesis of the polyunsaturated fatty acids in the phospholipid of arterial cells". Life Sciences. 74 (22): 2707–23. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2003.10.013. PMID 15043986.

- ^ Mojska H (2003). "Influence of trans fatty acids on infant and fetus development". Acta Microbiologica Polonica. 52 Suppl: 67–74. PMID 15058815.

- ^ Koletzko B, Decsi T (October 1997). "Metabolic aspects of trans fatty acids". Clinical Nutrition. 16 (5): 229–37. doi:10.1016/s0261-5614(97)80034-9. PMID 16844601.

- ^ Menaa F, Menaa A, Menaa B, Tréton J (June 2013). "Trans-fatty acids, dangerous bonds for health? A background review paper of their use, consumption, health implications and regulation in France". European Journal of Nutrition. 52 (4): 1289–302. doi:10.1007/s00394-012-0484-4. PMID 23269652. S2CID 206968361.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions: I can't find the Crisco green can anywhere". Crisco.com. Archived from the original on 18 February 2008.

- ^ "Final Determination Regarding Partially Hydrogenated Oils". Federal Register. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Nutritional Information". Crisco. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ "Palm Oil". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ "Phytosterol esters (Plant Sterol and Stanol Esters)". Institute of Food Science + Technology.

- ^ "Butter, salted". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. 1 April 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h The Culinary Institute of America (2011). The Professional Chef (9th ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-42135-2. OCLC 707248142.

- ^ "Oil, canola, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ a b c "Nutrient database, Release 25". United States Department of Agriculture.

- ^ Katragadda HR, Fullana A, Sidhu S, Carbonell-Barrachina ÁA (2010). "Emissions of volatile aldehydes from heated cooking oils". Food Chemistry. 120: 59. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.09.070.

- ^ "Oil, coconut, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Oil, corn, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Lard, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Peanut oil, proximates". FoodData Central, USDA Agricultural Research Service. 28 April 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ "Oil, olive, extra virgin, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Rice Bran Oil FAQ's". AlfaOne.ca. Archived from the original on 27 September 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ "Oil, soybean, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Beef, variety meats and by-products, suet, raw, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Nutrition data for Butter oil, anhydrous (ghee) per 100 gram reference amount"". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ "Sunflower oil, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Shortening, vegetable, nutrients". FoodData Central. USDA Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- William Shurtleff and Akiko Aoyagi, 2007. History of Soy Oil Shortening: A Special Report on The History of Soy Oil, Soybean Meal, & Modern Soy Protein Products, from the unpublished manuscript, History of Soybeans and Soy foods: 1100 B.C. to the 1980s. Lafayette, California (US): Soyinfo Center.