Reign of Juan Carlos I

| |

| Reign of Juan Carlos I November 22, 1975 – June 19, 2014 | |

| Seat | Bourbon |

|---|---|

|

| |

The reign of Juan Carlos I of Spain began on November 22, 1975, when the then Prince of Spain Juan Carlos de Borbón swore to the Fundamental Laws of the Kingdom before the Francoist Cortes after the death of dictator Franco, who had designated him as successor in 1969. It ended on June 19, 2014, when he abdicated in favor of his son Felipe de Borbón y Grecia, who swore to the Constitution of 1978 and was proclaimed king by the Cortes Generales with the name of Felipe VI.

Overview[edit]

The transition to democracy took place in the early years of his reign, making Spain no longer the only non-communist dictatorship left in Europe. The new king assumed the project of the reformist sector of Franco's political elite that, facing the conservatives, defended the need to introduce gradual changes in the fundamental laws so that the new Monarchy would be accepted in Europe as a whole.

This project was the one that his first government tried to implement, and it was presided by Carlos Arias Navarro, who had already headed the last government of General Franco. However, in view of the incapacity demonstrated by Arias Navarro, Juan Carlos appointed in July 1976 the Francoist "reformist" Adolfo Suárez as the new Head of Government to lead the process of transition to democracy without any "rupture" with the "previous regime". This is how the Political Reform Act came about, which was approved by the Francoist Cortes and revalidated in the referendum of December 1976. According to this new fundamental law, free elections to democratically elected Cortes were to be called.

Suarez's problem was to get the "controlled" transition process established in the Political Reform Act accepted by the democratic opposition, since the latter, in exchange for abandoning the "democratic rupture" and participating in the elections, demanded that Franco's institutions be dismantled and that all parties without exception ─ including the Communist Party of Spain ─ be legalized. Overcoming serious difficulties, President Suárez achieved these two objectives and the first free elections since 1936 could be held on June 15, 1977.

Union of the Democratic Centre (UCD), the party organized by President Suárez, won the elections, although not by absolute majority, and sought the consensus of the rest of the political forces ─ and especially of the other great winner, the PSOE ─ to create the new legal framework that was to replace the fundamental laws of the Franco regime, as well as to face the economic crisis, the reappearance of the "regional question" and the increase of terrorism by ETA. This led to the creation of the political transition to democracy model, which was based on the Amnesty Law of 1977 that included everything that had happened during the Franco dictatorship ─ thus constituting a so-called "pact of oblivion" ─[1][2] and in the approval of a Consensus Constitution in exchange for the leftist parties abandoning their claim to establish the Republic. On December 6, 1978, the referendum was held and the new democratic Constitution was approved.

Once the Constitution was endorsed, President Suárez called elections for March 1979, which were won by UCD but again without an absolute majority. During the following two years, the governing party suffered an acute process of internal decomposition that culminated with the resignation of Adolfo Suárez in January 1981. The following month an attempted coup d'état was staged by a sector of the army that sought to paralyze the democratic process and that only the decisive intervention of King Juan Carlos I managed to stop. After 23-F, the new UCD government presided by Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo managed to rule largely thanks to the support given by the PSOE and its leader Felipe González because the "self-destruction" of the UCD continued until October 1982, when new elections were held and were won overwhelmingly by the PSOE. Thus a party that had been one of the defeated parties in the civil war of 1936–1939 took power.

After 1982, the democratic system was consolidated and Spain experienced a long period of political stability in which there was alternation in government between the left and the right in a peaceful manner following the dictates of the elections (the PSOE governed between 1982 and 1996 and between 2004 and 2011; the People's Party, which emerged from the "refounding" in 1989 of the Alianza Popular, between 1996 and 2004 and between 2011 and 2014). It was decisive for the achievement of political stability that the positions of the two major parties on the most important issues were not antagonistic and that there were no major "social fractures", the latter thanks to the development of the Welfare state and "social protection" policies. Also during those years, Spain actively participated in the transformation of the European Community, which it joined in 1986, in the European Union and in the establishment of the common currency, the euro.

However, in the last six years of the reign, Spain suffered a very hard economic crisis that led to a political crisis, which also affected the Crown and which had not been resolved when Juan Carlos I announced on June 2, 2014, his decision to abdicate.

Transition (1975–1982)[edit]

In the first seven years of the reign of Juan Carlos I, the transition to democracy was completed, making Spain the only non-communist dictatorship left in Europe. The Spanish transition, of which the end is usually placed in the victory of the PSOE in the October 1982 elections, is part of the third "democratizing wave" of the 20th century, which began in Portugal in 1974 with the "Carnation Revolution" and ended with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.[3]

Proclamation of Juan Carlos I[edit]

In 1969, the dictator Francisco Franco designated Juan Carlos de Borbón as his successor "by title of king", by virtue of the Law of Succession to the Headship of the State of 1947. Juan Carlos held since then the title of Prince of Spain.[4]

After Franco's death in 1975, the Regency Council assumed interim power. Two days later, on November 22, 1975, Juan Carlos I was proclaimed king before the Francoist Cortes. After the speech Alejandro Rodríguez de Valcárcel, president of the Cortes, Juan Carlos I swore the Fundamental Laws of the Realm and then delivered a speech in which he avoided referencing Franco's triumph in the Spanish Civil War and in which, after expressing his "respect and gratitude" to Franco, he stated that he intended to reach "an effective consensus of national concord". In this way, he made it clear that he did not support the pure "immobilist continuism" advocated by the búnker ─ which defended the perpetuation of Francoism under the Monarchy established by Franco, following the model established in the Organic Law of the State of 1967─[5] but with a message to the Army to face the future with "serene tranquility" that hinted that the reform would be made from the regime's own institutions.[6][7] The most enthusiastic applause, however, was not for the new king but for General Franco's family present at the ceremony.[5] The anti-Franco opposition received the king's speech with coldness.[6]

The ratification of Carlos Arias Navarro as President of the Government caused an enormous disappointment,[8] barely mitigated by the appointment of Torcuato Fernández Miranda, former tutor to the prince, as the new President of the Cortes and of the Council of the Realm, key institutions in the framework left by the Franco dictatorship.[9] The disappointment was mitigated when the composition of the Government was known, in which the most prominent figures of Franco's "reformism" appeared, such as Manuel Fraga Iribarne, José María de Areilza and Antonio Garrigues y Díaz Cañabate. Other Francoist "reformists" from the Catholic (Alfonso Osorio) and Falangist "families" (the "blue reformists", Adolfo Suárez and Rodolfo Martin Villa) also participated in this government.[10] Actually, the members of the government were imposed on Arias Navarro by the king, and in the case of Suárez it had been a suggestion of Fernández Miranda.[11] This new government was often referred to for the press as the "Arias-Fraga-Areilza-Garrigues government".[12]

[edit]

Arias Navarro lacked a plan to reform the Franco regime[13][14] so his government adopted the one presented by Fraga Iribarne which consisted of achieving a "liberal" democracy that would be comparable to that of the rest of Western European countries through a gradual and controlled process from the power of gradual changes to the "fundamental laws" of Franco. That is why it was also known as "reform in continuity" and its support base would be what was then called "sociological Francoism".[15] With the democratic opposition it was not intended to negotiate or agree on any essential element of the process and from the elections would be excluded the "totalitarians", in reference to the communists.[15][16]

For its part, the PCE, then the main anti-Francoist opposition party, and the Junta Democrática, the political platform it had created in 1974, promoted a great mobilization against the "Francoist" Monarchy. There was agitation in the universities, demonstrations were held to the cry of "Freedom and Amnesty", violently dissolved by the police, and a wave of strikes was unleashed, much greater than the already very important ones of 1974 and 1975. The reasons for the strikes called by the illegal Workers' Commissions[14] were fundamentally economic ─ the seriousness of the "1973 oil crisis" was accentuated ─ but they also had political motivations since the demands for wage increases or improvements in working conditions were accompanied by others such as freedom of union, the recognition of the right to strike, freedom of assembly and association, when not directly demanding amnesty for political prisoners and exiles.[17]

The government's response was repression.[18] On March 3, 1976, the most serious incidents took place in Vitoria, which resulted in the death of five people by police gunfire. A general strike was immediately declared in the Basque Country and Navarre in solidarity with the victims, which had a huge following ─ also in other areas.[18] For much of the opposition, the "Vitoria massacre" showed the true face of the "Arias-Fraga reform" and demonstrations and strikes intensified, with subsequent clashes with the forces of law and order ─ in Basauri, near Bilbao, another worker died shortly afterwards.[19]

In spite of everything, the mobilizations did not have a sufficient following to overthrow the government, much less the "Francoist monarchy". It was thus becoming increasingly evident that the alternative of "democratic rupture" accompanied by "decisive national action" was not viable, so its main supporter, the Communist Party of Spain, decided in March 1976 to change strategy and adopt the alternative of "agreed democratic rupture" advocated by the moderate opposition and the PSOE ─ which had formed the Democratic Convergence Platform ─ although without abandoning the mobilization of citizens to exert continuous pressure on the government and force it to negotiate with the opposition.[20][21]

The change of strategy of the PCE, allowed the merger on March 26 of the two unitary organizations of the opposition, the Junta Democrática and the Plataforma de Convergencia Democrática, which led to the creation of Coordinación Democrática ─ popularly known as Platajunta. In its first manifesto, it rejected the "Arias-Fraga reform" and demanded an immediate political amnesty, full trade union freedom and a "rupture or democratic alternative through the opening of a constituent period". Thus, from the first scenario of rupture with popular uprising, the demand for the calling of general elections from which a constituent process could be derived.[22][23] Shortly after the Platajunta was formed the government tolerated the socialist trade union Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT) to hold inside the country its XXX Congress camouflaged under the term Jornadas de Estudio (Study Days), but at the same time the police arrested the leader of CC OO, Marcelino Camacho.[24]

Article featured in Newsweek magazine on April 25, 1976:The new Spanish leader [King Juan Carlos] is seriously concerned with right-wing resistance to political change. He believes the time for reform has come, but Prime Minister Carlos Arias Navarro, a holdover from the Franco days, has shown more stasis than mobility. The king is of the opinion that Arias is an unmitigated disaster, since he has become the standard-bearer of that group of Franco loyalists known as El Búnker. [...] Since he assumed the throne, the king has done his utmost to convince Arias, but has been met with a sixty-seven year old president whose reply is "Yes, Your Majesty" and does nothing, if not the opposite of what the king wants[...].

At the beginning of June 1976, the King visited the United States and in his speech before Congress, of whose exact content Arias Navarro was not aware, he ratified his commitment to provide Spain with a full democracy. Juan Carlos announced the Crown's will to "ensure the access to power of the different government alternatives, according to the freely expressed wishes of the Spanish people".[25] A month and a half earlier, Newsweek magazine had claimed that King Juan Carlos had told one of its journalists ─ which was never denied ─ that "Arias was an unmitigated disaster".[13] Around the same time Arias Navarro had made a statement on television in which he had made harsh attacks on the democratic opposition, while his relations with the king had deteriorated to the point that Arias had confessed to one of his closest collaborators: "It happens to me like with children; I can't stand him for more than ten minutes".[26]

After commenting to Areilza "this cannot go on, at the risk of losing everything ...",[26] Juan Carlos demanded Arias Navarro on July 1 to present his resignation, which he did immediately. A few days later, Torcuato Fernández Miranda succeeded in getting the Council of the Realm to include among the three aspirants for President of the Government the "king's candidate": Adolfo Suárez, a "blue reformist" who had not stood out too much until then.[26][27] Suárez's appointment caused enormous bewilderment and disappointment among the democratic opposition and diplomatic circles, as well as in newspaper editorial offices.[27] A political commentator that would end up becoming a minister under Suárez, wrote that his appointment had been an "immense mistake."[28][29]

The Suárez government (July 1976 – June 1977)[edit]

Adolfo Suárez formed a government of young Francoist "reformists", in which he did not include any prominent figures ─ Fraga and Areilza, refused to participate ─ but which did not lack political experience.[30][31][32] In his first statement, made before the TVE cameras, the new president presented his "reformist" project which contained important novelties of language and objectives and which caused a great impact on the majority of the population. He stated that his goal was to achieve "that the governments of the future be the result of the free will of the majority of Spaniards"[32] and, after expressing his conviction that sovereignty resided in the people, he announced that they would express themselves freely in a general election to be called for before June 30 of the following year. It was a matter of "elevating to the category of normal what at street level is simply normal."[33] Finally, Suárez announced that the "political reform" to be undertaken would be submitted to a referendum.[31]

The Political Reform Act bill, which was drafted jointly by the president of the Cortes, Torcuato Fernández Miranda, the vice-president of the government Alfonso Osorio and the Minister of Justice Landelino Lavilla, was very simple. A new Cortes was created, consisting of two chambers, the Congress of Deputies and the Senate, composed of 350 and 204 members respectively and elected by universal suffrage, except for the senators appointed by the king.[34] And at the same time, all the institutions established in the fundamental laws other than the Cortes were implicitly abolished, i.e. all the Francoist institutions without exception, so that the reform law actually liquidated what it was intended to reform.[35][36]

In addition, the new attitude of the government and especially that of its president changed the political climate, overcoming the tension that had been experienced during the government of Arias Navarro.[32] On July 31, the government approved the amnesty, one of the main demands of the anti-Francoist opposition, although "blood crimes" were excluded, so that many "Basque prisoners", alleged members of ETA, remained in jail.[35][14][30] This coupled with the fact that demonstrations in the Basque Country and Navarre were normally banned precisely because they included the request for amnesty for "Basque prisoners" and the claim for self-government which the authorities immediately linked to ETA activity ─ which continued with the attacks ─ would explain that there the climate of tension (and political radicalization) increased while in the rest of Spain it decreased.[35]

The obstacle that most worried the government to carry out the "political reform" was not what the democratic opposition could say, but rather the Army, that was considered the ultimate guarantor of "Franco's legacy". On September 8, Adolfo Suarez met with the military leadership to convince the high command of the need for reform. In that meeting they spoke of the limits that would never be crossed: neither the Monarchy nor the "unity of Spain" would be questioned; no responsibilities would be demanded for what happened during Franco's Dictatorship; no provisional government would be formed to open a constituent process; "revolutionary" parties would not be legalized ─ here the military included the Communist Party, their bête noire since the civil war. In short, the process leading to the elections would always be under the control of the government. Once the limits were clarified, the Army's misgivings were dispelled and Suárez got the go-ahead for the process he was about to undertake.[37][38]

The Political Reform Act bill began to be discussed in the Francoist Cortes on November 14, two days after a general strike called by the democratic opposition which had an appreciable following. Put to vote on November 18[39] the Suarez government obtained a resounding success when it was approved by 435 procuradores, while only 59 were opposed, 13 abstained and 24 did not vote. This was achieved with the invaluable collaboration of the president of the Cortes, Fernández Miranda: the Act was processed by the urgency procedure, which limited the debates and the final vote was not secret; the procurators who held high positions in the administration were warned that they ran the risk of losing them if they did not support the it; others were promised that they could renew their positions in the new Cortes that were to be elected by forming part of candidacies that the government was willing to support. This would explain why the Francoist Cortes had decided to "commit suicide" ─ to harakiri by their own decision, as some newspapers headlined the day after the vote.[40][41]

Once approved, the political reform referendum was convened for December 15. The government did not give any opportunity to the opposition to present its position ─ abstention ─ in the media it controlled, especially in the most influential one, the television ─ nor even in the radio ─ and deployed a formidable campaign in favor of the YES, so the result of the referendum did not bring any surprise: there was a high turnout, except in the Basque Country, and the YES won with 94.2% of the votes, while the NO, defended by the búnker, only got 2.6%.[35][42][43] The "Political reform", and implicitly the Monarchy and its government, were thus legitimized by the popular vote. From that moment on, the opposition's demand for the formation of a government of "broad democratic consensus" no longer made sense. It would be the Suárez government that would assume the task that the opposition had assigned to that government: to call general elections.[40][44]

During the last week of January 1977 the most delicate moment of the transition before the elections took place, as the Francoists in the búnker set out to stop the process of change by creating a climate of panic that would justify the intervention of the Army. The first provocation came in Madrid's Gran Vía, when a student, Arturo Ruiz, who was taking part in a pro-amnesty demonstration was killed by thugs of the extreme right-wing group Fuerza Nueva ─ in the demonstration protesting the crime a demonstrator, María Luz Nájera, was killed by a police smoke canister.[45] Two days later, the most serious event occurred: "ultras" gunmen burst into the office of some labor lawyers linked to the Comisiones Obreras and the Communist Party, located in Atocha street in Madrid, and put against the wall eight of them and a janitor, shooting then. Five members of the firm died on the spot and four others were seriously wounded.[46][47]

But the 1977 Atocha massacre did not achieve its objective of creating a climate evoking the civil war. On the contrary, it raised a wave of solidarity with the Communist Party, which gathered in the streets an orderly and silent crowd to attend the burial of the murdered communist militants. The Army, therefore, had no reason to intervene and not even the government decreed a state of emergency, as claimed by the extreme right.[48] And when it seemed that the crisis had been overcome the GRAPO reappeared, who like the extreme right also wanted to stop the process of political transition, and kidnapped the president of the Supreme Council of Military Justice, General Emilio Villaescusa Quilis ─ while they still held Antonio María de Oriol, president of the Council of State, hostage ─ and killed three policemen. But neither the Suárez government nor the Army fell for the provocation on this occasion either.[49]

The crisis of the "seven days of January" produced the opposite effect of those who intended to destabilize the system, since it accelerated the process of legalization of the political parties[50] and the dismantling of the Francoist institutions, without carrying out any kind of purge of their officials, who were transferred to other State bodies. On April 1, a decree established freedom of trade union[51] and shortly after, on Holy Saturday April 9, the Communist Party of Spain was legalized, which constituted the most risky decision taken by President Suárez in the whole transition.[45][52] The harshest reaction came from the Armed Forces. The Minister of the Navy, Admiral Gabriel Pita da Veiga, resigned and the government had to resort to a reserve admiral to fill his post, as none in active service wanted to replace him.

The Supreme Council of the Army expressed its compliance "in consideration of the national interests of superior order", although it did not refrain from expressing its contrary opinion. Some other high military commanders expressed their opinion that Suarez had "lied" to them in the meeting they had had with him on September 8 and that he had "betrayed" them. Thus, the legalization of the PCE became a "neuralgic point of the transition" because "it was the first major political decision taken in Spain since the civil war without the approval of the army and against its majority opinion".[49] The Communist Party in return had to accept the Monarchy as a form of government and the red and yellow flag,[53] and the Republican flags disappeared from its rallies.[54]

On May 13, the plane from Moscow landed in Madrid carrying on board the president of the PCE Dolores Ibárruri, the Pasionaria, who returned to Spain after a 38-year exile. The following day another exiled, Don Juan de Borbón, ceded his rights to the Spanish Crown to his son, King Juan Carlos I.[55] By the end May, Torcuato Fernández Miranda, "an important architect of the transition as president of the Cortes", presented his resignation from his post, which "seemed to indicate the beginning of a new political stage".[56]

Finally, on June 15, 1977, the general election took place without any incident and with a very high turnout, close to 80% of the census. The victory went to Unión de Centro Democrático, a coalition of moderate parties and "independents" led by Prime Minister Adolfo Suárez, although it failed to achieve an absolute majority in the Congress of Deputies ─ it obtained 34% of the votes and 165 seats: it was 11 seats short of an absolute majority.[57][58]

The second winner was the PSOE, which became the hegemonic party of the left, obtaining 29.3% of the votes and 118 deputies, ousting by a wide margin the PCE, which obtained 9.4% of the votes and remained with 20 deputies, even though it was the party that had borne the greatest weight in the anti-Francoist struggle. The Partido Socialista Popular of Enrique Tierno Galván was also ousted, obtaining only six deputies and 4% of the votes. The other big loser of the elections, together with the PCE, was the neofranquist Alianza Popular of Manuel Fraga who only obtained 8.3% of the votes and 16 deputies ─ 13 of whom had been ministers under Franco.[59] But the biggest setback was suffered by the Christian democracy of Joaquín Ruiz-Giménez and José María Gil Robles, the leader of the CEDA during the Second Republic, who did not obtain any deputies.[60][61] On the other hand, neither the extreme right nor the extreme left achieved parliamentary representation.[62]

After the elections, a party system called "imperfect bipartisanship" was drawn, where two large parties or coalitions (UCD and PSOE), which were located towards the political "center", had collected 63% of the votes and shared more than 80% of the seats (283 out of 350), and two other parties or coalitions were located, with much less support, at the extremes ─ AP on the right, PCE on the left. The exception to the imperfect bipartisanship was the Basque Country, where the PNV won 8 seats and the Euskadiko Ezkerra coalition 1, and Catalonia where the Pacte Democràtic per Catalunya led by Jordi Pujol won 11 and the Esquerra de Catalunya coalition 1.[60][63]

Adolfo Suárez's second government (1977–1979)[edit]

The measure that the newly elected deputies of the Cortes considered most urgent was to enact a total amnesty law that would free the prisoners who were still in jail for "politically motivated" crimes, including those "of blood". The left accepted that the law also covered people who had committed crimes during Franco's repression, which constituted a kind of "pact of oblivion" because, as the communist Marcelino Camacho, imprisoned during the dictatorship, said, "how could we reconcile those of us who had been killing each other, if we did not erase that past once and for all?".[64] However, despite the fact that the Amnesty Law released all the "Basque prisoners", ETA not only did not abandon "armed combat" but also increased the number of attacks ─ in 1978, it perpetrated 71 resulting in 85 deaths.[65]

An urgent issue that had to be addressed was the economic crisis that began in 1974. Minister of Economy Fuentes Quintana proposed the signing of a great "social pact" that would "compensate" the harsh adjustment measures that had to be taken through social improvements and some juridical-political reforms.[66][67] This led to the Moncloa Pacts signed on October 27, 1977,[68][69] which succeeded in stabilizing the economy and controlling inflation ─ from 26.4% in 1977 to 16.5 the following year ─[70] and social spending was increased in return ─ unemployment benefits, pensions, education and health spending ─ thanks to the tax reform implemented by Minister Francisco Fernández Ordóñez.[71]

Another pressing matter was the "regional question", since the demands for self-government on the part of Catalonia and the Basque Country did not admit any further delay. In the case of Catalonia, the restoration of the Statute of Autonomy approved by the Republic was demanded,[72] but Suárez opted to approve a decree-law of September 29, 1977, which "provisionally" restored the Generalitat although without reference to the 1932 Statute which allowed the return from exile of the "president" Josep Tarradellas.[71][73] For the Basque Country, the Basque General Council was constituted in December 1977 under the presidency of the socialist Ramón Rubial, but as in the case of Catalonia, the Statute of Autonomy approved by the Republic was not reestablished either.[73][74] The granting of a "pre-autonomy" regime to Catalonia and the Basque Country encouraged or "awakened" the "autonomist" movements in other regions, which the government channeled by proceeding to the constitution of pre-autonomy bodies in all those that claimed it.[65]

But the essential duty of the Cortes and the government was the elaboration of a Constitution. For this purpose, a Constitutional Affairs Commission was created in the Congress of Deputies, which in turn appointed a seven-member committee to present a preliminary draft. It was made up of three deputies from the UCD (Miguel Herrero y Rodríguez de Miñón, José Pedro Pérez Llorca and Gabriel Cisneros), one from the PSOE (Gregorio Peces Barba), one from the PCE-PSUC (Jordi Solé Tura), one from Alianza Popular (Manuel Fraga Iribarne), and one for the Basque and Catalan minorities (Miquel Roca).[75]

The rapporteurs set out to achieve a consensus text that would be acceptable to the major political forces so that when they alternated in government they would not have to change the Constitution.[76][77] While UCD gave in to the demands of the left for a broad text in which all fundamental rights and freedoms would be recognized, the PSOE and the PCE renounced the republican form of state in favor of the monarchy without the calling of a specific plebiscite on the subject, although they managed to make the powers of the Crown practically null and void.[78]

On the other hand, the state-level parties accepted the proposal of the Catalan nationalist, Miquel Roca, to introduce the term "nationalities" in the Constitution. One of the most critical moments, which almost broke the consensus, was the discussion of article 27 related to the "religious question", but finally a consensual wording was reached in which the "freedom of education" and the "freedom of creation of educational centers" were recognized ─ and therefore, the right of the Catholic Church to maintain its religious centers ─ but it was admitted that "teachers, parents and, if applicable, students will intervene in the control and management of all the centers supported by the Administration with public funds" ─ that is, not only the state centers, but also the private or religious centers subsidized by the State.[79] Other contentious issues were agreed upon by resorting to ambiguous wording of the articles, as occurred with abortion.[80]

The committee finished its work in April 1978 and the Constitutional Affairs Commission began to debate the preliminary draft on May 5. But the real negotiation was carried out outside the commission by Fernando Abril Martorell on behalf of the UCD and the government and the deputy secretary general of the PSOE Alfonso Guerra, who met privately to reach a consensus on the controversial issues, which allowed the rapid approval of the articles of the preliminary draft. The consensus was extended to Communists and Catalan nationalists but a part of Alianza Popular, which rejected among other things the incorporation of the term "nationalities", and the PNV, which demanded the recognition of the national sovereignty of the Basques, did not join it.[81][82]

Finally, on October 31, 1978, the Constitutional bill was voted in the Congress and in the Senate. In the Congress, 325 deputies voted in favor, 6 against (five deputies of AP and the deputy of Euskadiko Ezkerra), and 14 abstained (the 8 deputies of the PNV, plus 6 of AP and the mixed group).[83] In the Senate, 226 senators supported it and 5 voted against it. The Constitution thus obtained enormous parliamentary support.[76]

On December 6, 1978, the Constitution was submitted to referendum, being approved by 88% of the voters, and rejected by 8%, with a participation of 67.11% of the census. In the Basque Country, the abstentionist campaign promoted by the PNV was successful so that there the Constitution was approved by only 43.6% of the electoral roll.[84] It was also in the Basque Country where a higher percentage of negative votes was registered (23.5%). A different situation to that of Catalonia, where the level of participation was similar to that of the rest of Spain, and the positive votes exceeded 90%.[85]

Suarez's third government and the "23-F" (1979–1981)[edit]

Once the Constitution was approved, Adolfo Suárez dissolved the Cortes and called new elections.[86][87] The result did not satisfy either of the two major parties as things remained as they were in 1977. UCD won again but without reaching the absolute majority as it intended and the PSOE did not improve its results appreciably and remained in the opposition despite the fact that it had absorbed Tierno Galván's PSP. The same happened with AP, which ran under the name Democratic Coalition, and the PCE, which also failed to gain positions.[88][89][90]

A month after the general elections, the first municipal elections since the 2nd Republic took place, which this time resulted in the victory of the left, occupying the mayor's offices in most of the major cities thanks to the post-electoral pacts signed by the PSOE and the PCE. While the socialists Enrique Tierno Galván and Narcís Serra, occupied the mayoralties of Madrid and Barcelona, respectively, the communist Julio Anguita became the first communist mayor of a large Spanish city ─ Córdoba ─ of all its history.[91]

Failure to win the general election was a deep disappointment within the PSOE and opened the internal debate.[92] At the 28th PSOE Congress held in May 1979, the majority of delegates opposed the proposal of the leadership that to win the elections it was necessary to eliminate Marxism from the definition of the party. Then Secretary General Felipe González and the rest of the executive committee resigned.[92][93] However, at the Extraordinary Congress held in September 1979, Felipe González was acclaimed by the delegates and the Marxist definition of the party was removed.[94] This strengthened the leadership of Felipe González and culminated the process of "refounding" of the PSOE begun five years earlier at the Suresnes Congress.[95]

The most pressing issue the government had to address was the "autonomous" one, as both Catalans and Basques demanded the immediate processing of their respective statute projects, the Sau and the Guernica.[96] In the summer of 1979, Suárez negotiated the Basque Country Statute with the new president of the Basque General Council ─ the Basque nationalist Carlos Garaikoetxea ─ reaching an agreement that included the creation of an own police force and the reestablishment of the economic agreements. On October 25, it was submitted to a referendum in which 59.7% of the census participated, being approved by a very large majority.[97][98] The negotiation of the Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia, which obtained a similar level of self-government ─ although the system of agreements would not be implemented there ─ and similar institutions of its own, also culminated successfully. It was submitted to referendum on the same day as that of the Basque Country, being approved with an electoral participation similar to the Basque one.[97] Shortly thereafter, the first elections to the respective parliaments would be held, which gave victory to the PNV nationalists in the Basque Country (with Carlos Garaikoetxea as the new lehendakari) and to the Convergència nationalists in Catalonia (with Jordi Pujol as the new President of the Generalitat de Catalunya).[99][100][101]

The approval of the Basque and Catalan Statutes ─ and the discussion of the galician one ─ triggered the autonomic expectations of many regions so that the government, faced with the prospect of triggering a "carousel" of autonomic referendums, decided to "rationalize" the process.[102] The problem arose in Andalusia, where the first steps established by article 151 had already been taken to provide itself with a Statute with the same level of self-government as the Basque and Catalan ones, so the government was forced to call the autonomic referendum recommending at the same time the abstention of the voters. The referendum was held on February 28, 1980, and the result was that the autonomic initiative was approved by the absolute majority of the registered voters, which meant a disaster for the government and for the UCD.[99] The great beneficiary was the PSOE, which led the campaign in favor of the "YES" vote and from then on became the hegemonic political force in Andalusia.[103]

The setback suffered by the UCD in Andalusia was added to the defeat in the municipal and regional elections in Catalonia and the Basque Country. To this was added the worsening of the economic situation as a result of the "second oil crisis" of 1979 (the number of unemployed exceeded one million), the resurgence of ETA's actions which in 1979 and 1980 marked the peak of its activity (174 dead in attacks perpetrated by ETA in those two years, a good part of them military), the growing citizen "disenchantment", etc.[99][104] All this accentuated the political differences between the groups that made up UCD on various issues which opened a government crisis in mid-April 1980 that resulted in the formation of a new one whose "strong man" was the president's friend, Fernando Abril Martorell.[105][106][107] Felipe González then presented a motion of censure against Suárez, which although he did not succeed in getting it through made him the highest-rated political leader in the polls, unseating Adolfo Suárez for the first time,[105] and the PSOE became ahead of UCD in voting intentions.[107]

Suárez emerged very weakened from the Socialist motion of censure, which provoked a second crisis in his government in September 1980, which resulted in the departure of the former "strong man" Fernando Abril Martorell. However, the Christian-Democratic sector was not satisfied and started "a full-fledged rebellion".[108] The result was that on January 29, 1981, Adolfo Suárez made public on television his decision to resign from the presidency of the government and the party. He justified it with the enigmatic phrase: "I do not want the democratic system of coexistence to be, once again, a parenthesis in the life of Spain".[109][110] Two days later Suárez gathered the "barons" of UCD who agreed to propose Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo as candidate for the presidency of the government.[111][112][113]

The political crisis that the country was going through worsened when it was known that ETA had assassinated José María Ryan, industrial engineer of the Lemóniz Nuclear Power Plant who had been kidnapped a few days before, and coincided with the death by torture in the Carabanchel Penitentiary Hospital of the presumed etarra José Ignacio Arregui.[114] It also fueled the tension the signs of rejection that the kings received from representatives of Herri Batasuna when they visited the Casa De Juntas De Gernika together with the lehendakari Carlos Garaikoetxea.[115]

On February 22, Calvo Sotelo submitted his government program to the approval of the Congress of Deputies but did not reach the absolute majority, so the vote would have to be repeated the following day, and then a simple majority would be enough to obtain the investiture of the Chamber.[114] The afternoon of the 23rd, when the second vote was being taken, a group of armed civil guards under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Antonio Tejero burst into the Chamber of the Congress of Deputies.[116][117][118] At the same time, the Captain General of the 3rd Military Region, Jaime Milans del Bosch, declared a "state of war" in his demarcation to the cry of "Long live the King and long live Spain forever!", established a curfew, and ordered tanks to occupy the city of Valencia, seat of the captaincy general. Milans also contacted the rest of the Captain Generals so that they would second his initiative, alleging that he was waiting for the king's orders. Thus began a coup d'état that had been months in the making.[119]

The Crown, a symbol of permanence and unity of the Nation, shall not tolerate in any way actions or activities of individuals seeking to interrupt by force the democratic process determined by the Constitution approved by the Spanish people through a referendum. —Speech of King Juan Carlos I in the early morning of February 24.

When the King heard of what was happening, he ordered all the Captain Generals to remain at their posts and not to take the troops to the streets, and Milans del Bosch to order the tanks and soldiers occupying Valencia to return to their barracks.[120] Meanwhile, General Armada, another of the conspirators, tried to get the king to authorize him to appear on his behalf in the Congress of Deputies, but Juan Carlos I refused. In spite of this, Armada went to the Congress where he met with Tejero, to whom he explained his plan to form a concentration government presided by him and asked him to let him address the deputies. Tejero flatly refused because he wanted a purely military government.[120][121]

At one o'clock in the morning, the king, dressed as Captain General as supreme chief of the Armed Forces, addressed the country condemning the military coup and defending the democratic system. It was "the decisive moment to defeat the coup".[122] Two hours later, Milans del Bosch ordered the withdrawal of his troops and the next morning Tejero surrendered, releasing the government and the deputies. The coup of "23-F" had failed.[123] Shortly after, demonstrations in support of the Constitution and in defense of democracy were called, which were the largest of those held up to that time.[124]

The Calvo Sotelo government (1981–1982)[edit]

Although he rejected Felipe González's offer to form a broad-based parliamentary government,[125] Calvo Sotelo agreed with the PSOE on the two most urgent issues, the "military question" and the "regional question". Regarding the former, the Socialists agreed that only 32 of the more than 200 military personnel involved in the coup would be tried and only one civilian[126] ─ Tejero, Armada and Milans del Bosch were sentenced by the Supreme Court to the maximum penalty of thirty years in prison ─[127] and also supported the Law for the Defense of the Constitution aimed at preventing any new coup attempt.[128] Regarding the "regional question", UCD and PSOE agreed on the Organic Law for the Harmonization of the Autonomous Process (in Spanish, Ley Orgánica de Armonización del Proceso Autonómico or LOAPA) aimed at "reordering" the so-called "Regional state".[128][129][130]

The government did not find the support of the PSOE in the decision to apply for Spanish membership in NATO[131][132] and when it was approved in Congress on October 29, 1981, Felipe González promised that when he took power he would call a referendum on permanence.[133][134]

Calvo Sotelo did not manage to stop the internal crisis of UCD[135] ─ the "critical sector" led by Miguel Herrero y Rodríguez de Miñón and Oscar Alzaga approached Alianza Popular and the "social democratic sector" led by Francisco Fernández Ordóñez approached PSOE ─ which was aggravated by the defeat in the Galician elections of October 1981, in which the centrists were overtaken by Alianza Popular.[136] Calvo Sotelo then tried to recompose the unity of the party by personally assuming the presidency of the party and reshuffling his government, in which the "strong man" became the vice-president Rodolfo Martín Villa, but at the beginning of 1982, the "flight" of deputies to Alianza Popular began. In May, UCD suffered a new setback in the Andalusian autonomic elections, in which the PSOE obtained the absolute majority[137] and Alianza Popular again surpassed UCD in votes. Then Landelino Lavilla took over the presidency of the party but also failed to stop the "bleeding of splits". The Christian Democrats founded a new party, the Partido Demócrata Popular, and even Suárez left UCD to form his own, the Centro Democrático y Social.[138] Faced with this situation, a broken and disbanded party, Calvo Sotelo dissolved the Cortes in August 1982 and called general elections.[136][139]

In the elections of 1982, the PSOE won a resounding victory by obtaining an absolute majority in the Congress of Deputies (202 deputies) and in the Senate. The second most voted political force was the coalition formed by Alianza Popular and the Partido Demócrata Popular, which became with its 106 deputies the conservative alternative to the socialist power. The PCE (with 4 deputies) and UCD (with 12) were practically erased, as well as Suárez's Democratic and Social Center (which only obtained 2 deputies).[140][141]

With this result, described as an authentic "electoral earthquake", the party system underwent a radical change from the imperfect two-party system (UCD/PSOE) of 1977 and 1979 to a dominant party system (the PSOE).[142] The 1982 elections have been considered by most historians as the end of the political transition process initiated in 1975. Firstly, because of the high turnout, the highest ever recorded until then (79.8%), which reaffirmed the commitment of the citizens to the democratic system and showed that the "turn back" advocated by the involutionary sectors did not have the support of the people. Secondly, because for the first time the political alternation typical of democracies took place, thanks to the free exercise of the vote by the citizens. Thirdly, because a party that had nothing to do with Francoism was acceding to the government, since it was one of the defeated parties in the civil war.[140]

Gonzalez's socialist government (1982–1996)[edit]

After its victory in the October 1982 elections, the PSOE remained in power for almost fourteen years. It confirmed its absolute majority in the following two elections (1986 and 1989) and from 1993, although it lost it, it remained the most voted party and was able to continue governing thanks to the support of other groups. During this extended period, the consolidation of the Spanish democracy occurred, and Spain became a society fully comparable to that of its European neighbors.[143]

The socialist project[edit]

The political program developed by the governments presided by Felipe González was not a project of "socialist transformation" but of "modernization" of Spanish society to put it on a par with the rest of the "advanced" democratic societies.[144] The PSOE's electoral program was very ambitious as it aimed to consolidate democracy and face the economic crisis as well as to adapt the productive structures to a more efficient and competitive economy and to achieve a fairer and more egalitarian society with the universalization of health, education and pensions. This was synthesized in the slogan "Que España funcione" ("Let Spain work") thanks to a "gobierno que gobierna" ("government that governs").[145] However, the economic and political situation that Calvo Sotelo's government bequeathed to him was very complicated. Economic stagnation continued, with unemployment exceeding 16%, inflation not falling below 15% and a runaway budget deficit. ETA activity continued and the threat of a coup had not disappeared.[146][147]

The consolidation of the democratic system[edit]

The government of Felipe González understood that to consolidate the democratic regime in Spain it was necessary to put an end to its two main enemies: the "coup" and "terrorism". As for the former, a series of measures aimed at the "professionalization" of the Army and its subordination to civilian power were put in place with which the idea of an "autonomous" military power was completely discarded.[148] The government still had to face a last coup attempt in June 1985 which was dismantled by the intelligence services and that was not reported to the public until more than ten years later. Following this case, the coup attempts disappeared from Spanish political life.[147]

As for the anti-terrorist policy, the first socialist governments maintained the reinsertion of imprisoned separatists ─ many of them belonging to the ETA political-military faction ─ who condemned ETA's violence and dissociated themselves from it,[147] but in the face of under his mandate the "dirty war" against ETA led by the GAL was increased,[149] a "group initially made up of members of the State security forces and later swelled by some Spanish and foreign mercenaries linked to the former Political-Social Brigade of Francoism". Until 1987, the attacks of the GAL caused 28 fatalities, the vast majority of them in the so-called "French sanctuary".[150]

Simultaneously, the government tried a direct negotiation with the ETA leadership but the "Algiers talks" did not lead to any result; on the contrary, the group perpetrated some of the bloodiest attacks in its history: the Hipercor bombing, in Barcelona, and the Zaragoza barracks bombing. The government then sought to reach a great "anti-terrorist" pact that would also include democratic Basque nationalism, which was finally achieved with the signing of the Ajuria Enea Pact in January 1988.[151] A few months later, two policemen, José Amedo and Michel Domínguez were arrested, accused of being involved in the kidnapping of Segundo Marey among other crimes committed by the GAL, and with the aggravating circumstance that they had counted on the reserved funds of the Ministry of the Interior to carry out the attacks. The knowledge of this fact forced the Minister of the Interior José Barrionuevo to resign and he was replaced by José Luis Corcuera.[152]

The consolidation of the democratic system included the development of the rights and freedoms recognized in the Constitution of 1978. In the field of education, the Cortes passed the Organic Law for the Right to Education (in Spanish, Ley Orgánica reguladora del Derecho a la Educación or LODE), which, among other things, recognized and regulated the subsidies to be received by private educational centers, mostly religious, henceforth called "concerted" centers,[153][154] and the University Reform Act (in Spanish, Ley de Reforma Universitaria or LRU) which granted broad economic and academic autonomy to the Universities and established a system to achieve teacher stability.[155][156] The reform was accompanied by the creation of new universities and an increase in the number of scholarships, which resulted in an increase in university students whose number exceeded one million for the first time in 1990.[157]

The Cortes also passed the Habeas corpus law, the freedom of assembly law, the foreigners law and the Trade Union Freedom law.[158] The most controversial was the abortion law, passed in the spring of 1985, and which provoked the mobilization of Catholic sectors in defense of the "right to life". Alianza Popular appealed it before the Constitutional Court, but the latter ruled in favor of it.[159] Also controversial and the subject of an appeal before the Constitutional Court was the modification of the system of election of the members of the General Council of the Judiciary contained in the Organic Law of the Judiciary, but again the court ruled in favor of the law.[160][161]

As for the "regional issue", in addition to the approval of the few remaining autonomy statutes, an enormous decentralization of public spending took place, with the transfer to the autonomous communities of the powers determined by their respective statutes. By 1988, the average expenditure of the autonomous communities had already reached 20% of total public spending, and since then it has continued to increase. However, both the government of the Basque Country, presided since 1984 by "peneuvist" José Antonio Ardanza and that of Catalonia, presided since 1980 by the leader of CiU Jordi Pujol, continued to demand greater levels of self-government and opposed the "leveling" of all the autonomous communities, also accusing the government of curtailing their competences by resorting to organic laws.[162]

Foreign affairs (EEC and NATO)[edit]

The socialists proposed the full integration of Spain into Europe,[163] but when they took office the negotiations for the accession to the European Economic Community (EEC) were still blocked because of the "pause" in the enlargement imposed by the French president Giscard d'Estaing. However, the triumph in the presidential elections of the socialist François Mitterrand allowed rapid progress in the negotiations and so on June 12, 1985, the EEC accession treaty was signed and on January 1, 1986, Spain joined the EEC together with Portugal.[164][165]

After Spain's incorporation to the EEC, it was time to call the promised referendum on Spain's permanence in NATO. But Felipe González and his government ─ the Minister of Foreign Affairs Fernando Morán resigned when he disagreed ─ announced that they were going to defend Spain's remaining in NATO, under three mitigating conditions: the non-incorporation into the military structure, the prohibition to install, store or introduce nuclear weapons and the reduction of US military bases in Spain.[166][167] Faced with the PSOE's "turnaround", the banner of rejection of NATO was taken up by the Communist Party of Spain ─ now led by the Asturian Gerardo Iglesias who had replaced Santiago Carrillo ─ which formed a broad coalition of left-wing organizations and parties, from which United Left would emerge. Meanwhile, the "pro-Atlantist" Alianza Popular paradoxically opted for abstention, leaving the government alone.[168]

Against all expectations, Felipe González ─ who announced that he would resign if the "NO" vote won, which seems to have influenced many voters ─ finally managed to turn the polls around and the "YES" eventually prevailed in the referendum held on March 12, 1986, albeit by a narrow margin.[169] The result of the referendum, "the toughest test of his prolonged mandate",[170] strengthened Felipe González's leadership, both in his party and in the country as a whole, as could be seen in the general elections held that year, in which the PSOE again won an absolute majority. It was not unrelated to the fact that the economic crisis had been overcome and a phase of strong expansion had been entered, which would last until 1992.[171][172]

The social policies[edit]

Although its development began during the last stage of Franco's dictatorship and was developed during the transition under the UCD governments, the "Welfare state" comparable to that of the rest of the advanced European countries was completed during the socialist period. It was then that health care (the General Health Law was passed in 1986) and education (a new organization of the educational system was implemented in 1990 and compulsory education was extended to 16 years of age with the approval of the LOGSE) were extended to the whole population, and social spending on pensions and unemployment benefits, in addition to other social benefits, were considerably increased.[173]

This was possible because the Socialist governments increased the tax rate, which in 1993 was 49.7% of GDP, compared to 22.7% twenty years earlier,[158] taking advantage of the favorable economic situation of 1985–1992 when the Spanish economy overcame the crisis and grew above the European average.[173]

The economic policy and the split between PSOE and UGT[edit]

The Minister of Economy and Finance of the first socialist government Miguel Boyer and his successor from 1985 Carlos Solchaga applied a policy of adjustments and wage moderation to clean up the economy and reduce inflation. They managed to bring the rise in prices below 10% but at the cost of rising unemployment, which in 1985 exceeded 20% of the working population, a record figure,[174] although two other variables intervened in its growth: the entry into the workforce of the baby boom generation of the 1960s and the massive incorporation of women.[175] Also, the first socialist government reformed in 1984 the Workers Statute with the aim of "flexibilizing" the labor market which ended up causing a "precarization" of employment, by considerably increasing temporary contracts as opposed to permanent ones.[158]

In addition, it was also concerned with the "modernization" of productive structures, through an ambitious program of "industrial reconversion". Obsolete or ruinous companies were closed and credits were given to companies to introduce the necessary technological improvements to make them more competitive, among other measures. The most affected sectors were the steel and shipbuilding industries, especially the large public companies inherited from Franco's regime. Not coincidentally, it was in these sectors where the most important conflicts took place, with a proliferation of clashes between workers and the forces of public order, the most serious being those of Sagunto.[176] This program was accompanied by heavy investments in infrastructure ─ thanks mainly to the European funds that arrived after the entry into the EEC ─ which allowed Spain to equip itself with a network of highways and freeways and to start the construction of the first high-speed rail line between Madrid and Seville that started operations in 1992.[173]

The positive effects of the economic policy started to show after 1985, when the Spanish economy began a strong expansion that would last until 1992.[177] However, during those years there was also an increase in speculative capital movements led by people linked to the world of finance who were looking for easy enrichment.[178]

It was in this context that the UGT and the PSOE broke up for the first time in their history. The rift began when the government stopped applying the electoral program that in economic and social matters the PSOE had agreed with UGT and instead implemented a harsh economic policy of adjustments, "flexibilized" the labor market and began the "industrial reconversion", in addition to delaying the introduction of the forty-hour workweek.[179][180]

The first public confrontation occurred in 1985, on the occasion of the Pension Bill, not agreed by the government with the UGT, that increased from 10 to 15 the years of contribution necessary to be entitled to receive a pension and extended from two to eight years the contribution period for the calculation of the pension. The secretary general of UGT Nicolás Redondo, a socialist deputy in Congress, voted against the law and Felipe González stopped attending the May 1 demonstration.[181] The definitive rupture was staged before the television cameras on February 19, 1987, during the bitter debate between Nicolás Redondo and the then Minister of Economy and Finance Carlos Solchaga. A few months later Redondo left his seat in the Congress of Deputies, together with the also leader of UGT Antón Saracíbar.[182]

The rupture resulted in confrontation when the government presented its Youth Employment Plan which UGT and Comisiones Obreras rejected and which motivated the call for a general strike on December 14, 1988, under the slogan "Por el giro social" ("For the social turn").[183] The strike was a total success and the country was completely paralyzed.[184][185]

The socialist decline (1989–1996)[edit]

The Fourth Government (1989–1993)[edit]

Felipe González called general elections for October 1989, in which he again renewed his absolute majority but this time by only one seat.[186] The People's Party born from the "refoundation" of Alianza Popular carried out in the extraordinary Congress held in January of that same year, ran in the elections. As candidate for the presidency of the government, Manuel Fraga proposed José María Aznar, then president of the Junta of Castile and León. The "re-founded" PP won 25.6% of the votes and 107 seats, and in March 1990, during the 10th Congress, Aznar was elected president of the PP, while Manuel Fraga held the presidency of the Xunta de Galicia after winning the autonomous elections held in December 1989.[187]

The first of the scandals that gradually undermined confidence in the PSOE and its government was the "Guerra case", named after the brother of the vice-president of the government who was accused of illicit enrichment and influence peddling. At first Alfonso Guerra refused to resign[188] and the PSOE leadership supported him,[189] but finally Felipe González had no choice but to dismiss him in January 1991.[190] The departure of Alfonso Guerra's government deepened the internal division of the PSOE that had manifested itself in the 32nd Congress held in November 1990 and triggered a dull struggle between guerristas and renovadores that worsened with the outbreak in May 1991 of a new corruption scandal, the "Filesa case", which this time involved the whole party.[190][191] Judge Marino Barbero indicted 39 people, eight of whom would be sentenced in 1997 by the Supreme Court to sentences ranging from eleven years in prison to six months in prison.[192]

A third corruption case that splashed the PSOE was the "Ibercorp case", known in February 1992 and also uncovered by the newspaper El Mundo, and the one involving governor of the Bank of Spain Mariano Rubio which forced the former Minister of Economy and Finance Carlos Solchaga, who had appointed him, to resign as deputy.[192][193] The PSOE was so questioned that it "exhibited an almost total lack of credibility" when it filed the denunciation of a corruption case involving the Popular Party, the "Naseiro case", by the name of the "treasurer" of the PP Rosendo Naseiro.[194]

In the midst of this political climate, the two major events planned for 1992 ─ the 1992 Summer Olympics and the 1992 Seville Expo ─ were held, which provided "the opportunity to present Spain in the Columbus Quincentenary as a modern country, definitely away from the romantic stereotype (of charanga, tambourine, bandits and toreros)".[195] This new image of Spain was accompanied by the strengthening of its international role, such as the holding in Madrid of the Middle East Peace Conference and the active participation of Felipe González in the approval of the Maastricht Treaty which transformed the European Community into the new European Union. Likewise, the Spanish government sent three Navy units to support US-led allied military operations during the First Gulf War of 1990–1991.[196]

However, the two great events of 1992 and the resounding success of the anti-terrorist policy that led to the arrest of the three top leaders of ETA in the French town of Bidart, could not hide the fact that a strong economic recession had begun, which resulted in a brutal increase in unemployment that would reach an unprecedented figure of 3.5 million unemployed, representing 24% of the working population.[197] Also that same year, a general strike called by UGT and Comisiones Obreras occurred in protest against the government's "decretazo" cutting unemployment benefits.[198] The deteriorating economic situation and social climate, together with internal divisions within the PSOE, led Felipe González to bring forward the general elections to June 1993.[199][200]

The "legislature of tension" (1993–1996)[edit]

In the elections of June 1993, the PSOE won again and the People's Party of José María Aznar, who was convinced of his victory, was defeated.[199] The PSOE won 159 seats to 141 for the PP, while United Left, led by Julio Anguita won 18 deputies.[201][202] As the Socialists did not renew the absolute majority they had held since 1982 (17 seats short) Felipe González had to reach a parliamentary agreement with the Catalan and Basque nationalists to be invested again as president of the government.[202]

The most pressing task of the new government was to face the economic crisis. The Minister of Economy and Finance Pedro Solbes presented at the end of 1993 a package of Urgent Measures for the Promotion of Employment, which was responded by the UGT and CC OO unions with the call for a general strike for January 27, 1994, which was a great success.[203] In contrast, the Socialist government did obtain the backing of the unions and the rest of the political forces on the issue of pensions, the result of which was the so-called Toledo Pact of April 1995.[204] Another important field of government action was foreign policy, in which the Spanish participation in NATO's intervention in the Yugoslav War stood out, and which resulted in the appointment of the then Socialist Minister of Foreign Affairs Javier Solana as Secretary General of NATO.[205]

Yet, the main problem that the socialist government of Felipe González had to face was the appearance of new scandals, which resulted in a harsh confrontation with the opposition, both the People's Party and the United Left, so that the fourth socialist mandate would be known as the "legislature of tension."[206][207]

The one with the greatest popular and media impact was the "Roldán case", named after the then director of the Civil Guard, Luis Roldán, who was arrested accused of having amassed a fortune thanks to his position and who four months later, in April 1994, went on the run.[208] The former Interior Minister who appointed Roldán, José Luis Corcuera, had to resign as a deputy, as did the Interior Minister at the time, Antoni Asunción, for letting him escape.[193] Roldán was arrested a year later in Laos and sent back to Spain where he was tried and sentenced to 28 years in prison.[209]

It was in this context that the European Parliament elections of June 1994 occurred, in which the People's Party for the first time surpassed the PSOE in number of votes ─ it obtained 40% of the suffrages against 30% for the Socialists ─[210] which led them to demand the holding of general elections and to ask for the resignation of Felipe González.[207][211]

A month before the European elections, Judge Baltasar Garzón, who had been "number two" on the Socialist lists for Madrid, had left his seat in Parliament and the post of Government Delegation for the National Plan on Drugs, and had immediately reopened the GAL case. Shortly afterwards, several high-ranking officials of the socialist administration and the PSOE (Julián Sancristóbal, Rafael Vera and Ricardo García Damborenea) were arrested for their alleged participation in the kidnapping and frustrated murder of the French citizen Segundo Marey. As the former Minister of the Interior José Barrionuevo, a Socialist deputy, was also implicated, Garzón had to pass the "Marey case" to the Supreme court and Judge Eduardo Moner took charge of the investigation, who in January 1996 also charged Barrionuevo.[212][213]

A year before, another big scandal related to the "dirty war" against ETA had been uncovered. On that date the Civil Guard general Enrique Rodríguez Galindo was arrested for his alleged involvement in the "Lasa and Zabala case", the kidnapping and subsequent murder of José Antonio Lasa and José Ignacio Zabala, alleged members of ETA.[214][215] Shortly thereafter another new scandal broke out, known as the "CESID papers", which forced the resignation of the vice president of the Narcís Serra government and the Minister of Defense Julián García Vargas.[215][216]

Faced with the accumulation of scandals, the leader of CiU and president of the Generalitat de Catalunya, Jordi Pujol, withdrew the parliamentary support of the CiU deputies to the government, leaving the latter in a minority in the Cortes. The president of the government Felipe González had no choice but to call general elections for March 1996.[216][217] The People's Party won the elections ─ it obtained 156 deputies, 15 more than the PSOE ─ and thus achieved its goal of ousting the Socialists from power,[216] "after trying hard for more than a decade".[211]

Aznar's government of the people (1996–2004)[edit]

The People's Party (PP) held the government under the presidency of José María Aznar for eight years. During his first term (1996–2000), having failed to obtain an absolute majority, the PP had to rely on the support of the CiU Catalan nationalists to govern,[218] but in his second term (2000–2004) he had no need for pacts having obtained an absolute majority in the general election of March 2000.[219][220]

Socio-economic policy[edit]

The economic program implemented by the Popular Party set as immediate objectives to improve the efficiency and competitiveness of the economy with the liberalization of the markets of certain sectors[221][full citation needed] and with the complete privatization of public companies, such as Telefónica or Repsol; to reduce inflation through the control of public spending and the consequent reduction of the budget deficit ─ until reaching "deficit 0" ─ and the "wage moderation" to be agreed with the trade unions; and "making the labor market more "flexible", promoting the "social dialogue" to reduce severance payments and thus encourage permanent hiring ─ the agreement between the CEOE, UGT and CC OO and the government was actually signed in April 1997.[222][223][224] The ultimate purpose of these measures was to comply with the requirements imposed by the European Union in order to adopt the new common currency, the euro. And in this field the success was complete because the Spanish economy experienced strong growth, unemployment was reduced and inflation fell to historic lows, so that in May 1998, Spain could be part of the group of eleven European Union countries that adopted the euro, although it was not until January 1, 2002, that euro banknotes and coins physically began to circulate.[225][226][227]

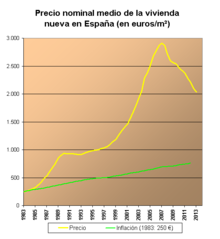

The other side of the strong economic growth of these years was the "property bubble" that it generated since the main economic "engine" was the construction of houses and the demand for them was due to the fact that many savers did not buy them to inhabit them but as an investment to sell them later at a higher price, thanks to the constant increase in their value. Also the acquisition of a home became one of the most pressing problems for many people, especially for young people.[228]

The favorable economic situation made it possible to make the maintenance of social spending (education, health, pensions) compatible with the reduction of the public deficit and with the reduction of direct taxes.[225][229] On the subject of pensions, the PP reaffirmed the validity of the so-called Toledo Pact and presented in the Cortes a bill ─ which was passed in 1999 ─ for the automatic revaluation of pensions, and the Social Security also managed to overcome the deficit it had in 1995 thanks to the spectacular increase in the number of affiliates.[222][230]

The Aznar government did not obtain the same support when it proposed the reform of the 1985 Foreigners' Law[231][232] and conversely, the events that took place in El Ejido in early 2000 ─ dozens of Moroccans were attacked by a large group of neighbors in response to the murder of a woman attributed to a mentally ill man of Maghrebi origin ─ highlighted the problem of xenophobia in relation to emigration in all its crudeness.[233]

Change in anti-terrorist policy and "peripheral" nationalisms[edit]

The PP government developed an anti-terrorist policy based on an idea that no democratic government had defended until then: that only police measures could put an end to ETA. Thus, the only possible "dialogue" with ETA was the handing over of weapons.[234][235]

The government reaped a resounding first success with the release in early July 1997 of José Ortega Lara, a prison officer and PP militant who had been held hostage by ETA for 532 days. But a few days later, on July 10, an event took place that would open a new stage in the history of the "Basque conflict". That day ETA kidnapped Miguel Ángel Blanco, a young PP councilman from the Biscayan town of Ermua, which provoked the largest social mobilization against terrorism in living memory. But after the deadline given for the prisoners of the organization to be transferred to prisons in the Basque Country, ETA assassinated Miguel Ángel Blanco, which increased even more the rejection of ETA and its "political arm", Herri Batasuna. The press began to use the term "spirit of Ermua" to explain that immense anti-terrorist social mobilization.[233][236]

In March 1998, the lehendakari José Antonio Ardanza announced a "Pacification Plan" in which, based on the Ajuria Enea Pact of 1988, he proposed that after achieving the cessation of ETA's violence, a dialogue should be opened between all the Basque political forces, the result of which should be accepted by the central government and the rest of the institutions of the State. Both the PP and the PSOE refused to participate in the proposed dialogue under those conditions, which meant "the demise of the Ajuria Enea Mesa, which would never reconvene again."[237]

After the failure of the "Ardanza Plan", the PNV, EA and HB ─ and also the United Left of the Basque Country ─ signed the Treaty of Estella on September 12, 1998, and four days later ETA announced the indefinite cessation of violence. Thus, 1999 was the first year since 1971 without any deaths from ETA attacks, although the street violence of the kale borroka did not disappear.[238][239]

During the truce, the PP government even made contacts with the ETA leadership but maintained the idea expressed by Interior Minister Jaime Mayor Oreja that it was a "trap truce", that is, that ETA had proclaimed the cessation of violence only to reorganize itself after the hard police blows it had received.[240][241][242] In November 1999, ETA announced the breaking of the truce due to the lack of progress in the Basque "process of national construction" and in January 2000 it perpetrated a new attack. Another of the "reasons" for ending the truce had been that neither the 1998 Basque Parliament elections nor the municipal and foral elections of June 1999 had resulted in an overwhelming victory of the parties supporting the "Lizarra Pact" against the "constitutionalist" parties.[243][244]

Throughout the year 2000, ETA committed several attacks against leaders and elected officials of the "constitutionalist" parties that had opposed the "Lizarra Pact" and the PP and the PSOE decided to sign an Antiterrorist Pact, which neither the PNV nor EA joined. This pact, together with the legal encirclement of Batasuna, and the increasing police effectiveness weakened ETA to such an extent that the number of attacks was reduced. However, the confrontation between "nationalists" and "constitutionalists" did not diminish as was evidenced in the Basque elections of May 2001 in which the "nationalist front" triumphed, and the "peneuvist" Juan José Ibarretxe assumed the presidency of the Basque government.[245]

As a result of the relative failure of the "constitutionalist front" in the Basque elections of May 2001, the PP government proposed the outlawing of Herri Batasuna ─ at that time integrated in the Euskal Herritarrok coalition ─ for which it agreed with the PSOE and CiU a new Law of Political Parties. Thus, after the attack perpetrated by ETA in Santa Pola in August 2002 ─ which caused the death of two people and which Batasuna did not condemn ─ the process of outlawing began, which was accompanied by the "suspension" of Batasuna's activities by order of Judge Garzón, having found evidence of its connection with ETA.[239] In early 2003, the Supreme Court declared Batasuna illegal as it was considered the "political arm" of ETA. Both the new Law of Political Parties and the process of illegalization of Batasuna were strongly contested by the Basque nationalist parties and, as an alternative, the lehendakari Juan José Ibarretxe proposed a "pacification plan" based on the holding of a referendum regulating "the free association of Euskadi to the plurinational Spanish State".[246]

By the end of 2003, the tension between the central government and the "peripheral" nationalisms moved to Catalonia as a result of the formation of a left-wing "tri-party" government after the Catalan elections of November 2003 consisting of the Socialists' Party of Catalonia (PSC), Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC, a pro-independence party that had experienced a meteoric rise), and Initiative for Catalonia Greens (a party associated with United Left) and presided by the socialist Pasqual Maragall. The "Tinell Pact" of the PSC-PSOE, IC and ERC (in which the "tri-party" program was agreed, expressly excluding any agreement with the PP) was harshly criticized by the Aznar government and by the new PP leader Mariano Rajoy ─ who at the end of August 2003 had been proposed by Aznar to replace him as candidate in the following year's elections.[247][248]

By the end of January 2004, a scandal broke out that shook the "tri-party" government. In its 24th edition, the newspaper "ABC" published that the leader of ERC, Josep Lluís Carod Rovira, conseller en cap of the Generalitat, had met in Perpignan with the top leadership of ETA to negotiate an exclusive truce for Catalonia. Carod left the government after acknowledging that the meeting with ETA had taken place, but affirming that he had not negotiated anything, least of all a truce restricted to Catalonia. However, a few days later ETA declared a truce "only for Catalonia with effect from January 1, 2004."[249]

Foreign policy shift[edit]

From the outset, the Aznar government was committed to greater Spanish involvement in international actions.[250][251] Thus, the need to seek a new model of Armed Forces that would make them more operational was raised, which, together with the spectacular growth of conscientious objector inclined the PP towards the formula of an exclusively professional army by putting an end to compulsory military service ─ thus abandoning the mixed model implemented by the Socialists.[252][253]