1947 Rawalpindi massacres

| 1947 Rawalpindi massacres | |||

|---|---|---|---|

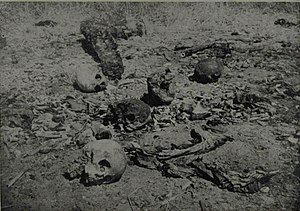

Skeletal remains of people burned to death at Thamali during the Rawalpindi massacres | |||

| Date | March 1947 | ||

| Location | Rawalpindi Division, Punjab, British India | ||

| Caused by | Muslim mobs | ||

| Goals | |||

| Methods | |||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 2,000 – 7,000 | ||

The 1947 Rawalpindi massacres (also 1947 Rawalpindi riots) refer to widespread violence, massacres, and rapes of Hindus and Sikhs by Muslim mobs in the Rawalpindi Division of the Punjab Province of British India in March 1947. The violence preceded the partition of India and was instigated and perpetrated by the Muslim League National Guards—the militant wing of the Muslim League—as well as local cadres and politicians of the League, demobilised Muslim soldiers, local officials and policemen.[1][2] It followed the fall of a coalition government of the Punjab Unionists, Indian National Congress and Akali Dal, achieved through a six-week campaign by the Muslim League. The riots left between 2,000 and 7,000 Sikhs and Hindus dead, and set off their mass exodus from Rawalpindi Division.[3][4] 80,000 Sikhs and Hindus were estimated to have left the Division by the end of April.[5] The incidents were the first instance of partition-related violence in Punjab to show clear manifestations of ethnic cleansing,[6][7] and marked the beginning of systematic violence against women that accompanied the partition, seeing rampant sexual violence, rape, and forced conversions, with many women committing mass suicides along with their children, and many killed by their male relatives, for fear of abduction and rape.[8][9] The events are sometimes referred to as the Rape of Rawalpindi.[a]

Background[edit]

In the 1946 Punjab provincial election, the Muslim League (ML) won 75 of the 86 Muslim seats in the province and emerged as the biggest party, but failed to win any non-Muslim ones and fell short of the magic figure in the 175 seat assembly.[b] The Muslim zamindar-led secular Unionist Party, which had won 18 seats, of whom 10 were Muslim, formed a coalition government with the Indian National Congress, which was the second biggest winner after the ML, winning 51 seats, and the Shiromani Akali Dal, which had won 20 seats, all from Sikh constituencies.[c] The Unionist leader Khizar Hayat Tiwana was elected the premier.[14]

After withdrawing from the Cabinet Mission plan in July 1946, Muslim League leader Muhammad Ali Jinnah called for “Direct Action” in August. The calls for direct action were followed by large-scale rioting and violence in Calcutta, which gradually spread elsewhere during the following months.[15][d] In December 1946, rioting was reported from the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) after a Muslim League campaign to oust the Congress government in that province.[17] The neighbouring Rawalpindi Division received thousands of Hindu and Sikh refugees who had been driven out from the Hazara district of NWFP.[18][19] In January 1947, Tiwana banned the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and the Muslim League National Guard, which prompted large “direct action” demonstrations by the Muslim League throughout the province that later turned violent.[20][21] The Muslim League campaign worsened communal tensions in the province, which had already been raised after previous year's election campaign.[22] On 20 February 1947, British Prime Minister Clement Attlee announced that the British will leave India by June 1948.

Events[edit]

On 2 March 1947, Khizar Hayat Tiwana resigned as premier in light of the Muslim League agitations and campaign against his ministry, and the official announcement of the imminent end of British rule.[16][17] Although anticipated, a Muslim League-led coalition could not form due to the League's inability to assuage the fears of non-Muslim legislators, who had become increasingly hostile to the League and the demand for Pakistan.[23][e] Akali Dal leader Master Tara Singh notoriously made a public spectacle of his disapproval of the Pakistan demand outside the Punjab Assembly on 3 March.[24][25] Communal clashes erupted in Lahore and Amritsar on 4 March after Hindus and Sikhs began demonstrations against the Pakistan demand. On 5 March, which marked the Hindu festival of Holi, armed Muslim mobs started attacking Hindus and Sikhs in several cities of West Punjab, including the cantonment town of Rawalpindi and Multan, killing close to 200 in the latter with the casualties being mostly Hindu.[26][27] Several villages in the Multan District were attacked after dark, and many Hindus were killed and their properties looted or destroyed.[28] With no government in sight, Governor Evan Jenkins imposed governor's rule in Punjab.[29]

The rioting soon spread from the towns to the rural areas of Rawalpindi Division in northern Punjab. Faced with resistance from the Sikhs and Hindus in the divisional headquarters of Rawalpindi, Muslim mobs banded together and turned to the countryside.[30][17][31][f] The mobs went on a rampage, engaging in arson, looting, massacres and rape, one village after the other in the districts of Rawalpindi, Jhelum and Cambellpur (present-day Attock). Sikhs were the primary targets, but Hindus were also attacked. In one incident, on 7 March, a train was raided by a mob at Taxila, which killed 22 Hindu and Sikh passengers.[33] Houses in the Sikh and Hindu quarters of the village of Kahuta were torched with their occupants present inside, while women were abducted to be raped.[34]

The village of Thoha Khalsa was the site of a much-publicised massacre. An armed Muslim mob laid siege to the village, asking the Sikh residents to convert to Islam. Sikh men killed female members of their families to prevent their abduction and rape, before being killed themselves by the attackers. More than 90 Sikh women and children committed mass suicide after jumping into a well to avoid rape.[35][5][36][37] The death toll at the village is estimated to be around 300. A similar massacre, mass suicide and looting also took place at the village of Choa Khalsa, where around 150 Sikhs—and a smaller number of Hindus—were killed,[37] and in the Sikh village of Dhamali.[38]

In Bewal village, a house where villagers had taken refuge was besieged and villagers were asked to surrender their arms and convert to Islam. One group of the villagers took up the offer and were subsequently converted, while the remaining were periodically attacked. The house was set on fire, following which the villagers shifted to a Gurdwara where they were attacked and massacred. One survivor claimed that out of a total of 500 Hindu and Sikh villagers, only 76 had survived, of whom nearly half had been abducted.[39] Similar attacks happened at the villages of Mughal and Bassali.[40] Kallar, Dubheran, Jhika Gali and Kuri were also attacked.[41][42] Some of the survivors had been left disfigured and mutilated, breasts of many women who had been raped were cut-off.[43] Villages in the Gujar Khan and Cambellpur districts were decimated, dead bodies of children were found hanging from trees and girls as young as eleven had been gang-raped.[42] The All India Congress Committee, in its report on the violence, described the strategy of the attacks as follows:[44][undue weight? ]

First of all minorities were disarmed with the help of local police and by giving assurances by oaths on holy Quran of peaceful intentions. After this had been done, the helpless and unarmed minorities were attacked. On their resistance having collapsed, lock breakers and looters came into action with their transport corps of mules, donkeys and camels. Then came the ‘Mujahadins’ with tins of petrol and kerosene oil and set fire to the looted shops and houses. Then there were maulvis with barbers to convert people who somehow or other escaped slaughter and rape. The barbers shaved the hair and beards and circumcised the victims. Maulvis recited kalamas and performed forcible marriage ceremonies. After this came the looters, including women and children.

Similar accounts of the attacks are recounted in first information reports (FIRs) given to the police by survivors.[45]

The attacks were premeditated, and rumours were spread through mosques to instigate Muslim villagers.[46][47] The attackers are said to have received weapons and funds from outside, and were partly funded by the Muslim League.[48] They were armed with guns, rifles, axes, swords, spears, sticks, and in two cases with hand grenades.[49] Houses of those driven out were razed and subsequently flattened up to prevent them from returning and rebuilding.[50][51] Muslim houses were sometimes marked by their occupants to allow the attackers to distinguish them from houses of non-Muslims.[28] The ancestral home of Tara Singh was also reduced to ashes. The mobs continued their campaign of loot and mass murder without hindrance.[50] Muslim policemen aided and abetted the violence at many places throughout West Punjab, and at times responded inordinately late to appeals for help.[52][g] There is evidence of involvement of Muslim League cadres and local politicians in the attacks,[54] but little evidence directly implicating the top leadership of the Muslim League—including Jinnah.[46] However, no leaders of the Muslim League, national or provincial, offered any condemnation of the massacres.[55][h]

Aftermath and Impact[edit]

The violence ceased by the middle of March.[i] At many places, attacks ended after the army moved in to rescue survivors. Many villages had their entire population wiped out while others had few survivors.[56] The official death toll for non-Muslims killed in the Rawalpindi district alone stood at 2,263,[j] however, this number was considered inaccurate due to "the widespread nature of disturbances" and a collapse of "normal administrative machinery".[57] The number was based on registered police cases and did not include such cases "where whole families were wiped out and no claims were made".[57] A contemporary Shiromani Gurudwara Prabandhak Committee report put the number of dead at over 7,000.[58] Later scholars have given estimates ranging between 4,000 and 8,000 dead in the rural areas of Rawalpindi.[59][60]

Many women were abducted during the violence. 70 were abducted from the Doberan village, 40 from Harial, 30 from Tainch, 95 from Rajar and 105 from Bamali. A further 500 were abducted from Kahuta and between 400 and 500 were abducted from Rawalpindi. Abducted women were often sold multiple times and raped by their captors.[61]

The massacres triggered a mass-migration of Sikhs and Hindus from the Rawalpindi Division to central and eastern Punjab, Sikh-ruled princely states, Jammu and Kashmir, Delhi and the United Provinces. The descriptions of atrocities faced by these refugees provoked feelings of revenge, especially among the Sikhs.[62][63][64] The massacres had a deep impact on the Sikhs and Hindus of the Punjab, who planned to avenge them later by unleashing similar violence on the Muslims of the eastern portions of the province, to make way for the settlement of the refugees who had been driven out from the west.[5][65][66][67] The Sikhs, in particular, felt especially humiliated as parts of the Muslim press taunted them after the massacres.[68] The absence of condemnation of the massacres by leaders of the Muslim League widened the growing rift between the League and the Sikhs.[69] The riots also lead to the Congress and Sikh leaders of the Punjab demanding its partition.[70] On 8 March, the Congress Working Committee passed a resolution to partition the Punjab.[71][72]

Survivors identified attackers by their names, occupations and home villages in FIRs after the massacres.[73] Despite identification by fact-finding committees, few of the perpetrators were ever brought to justice, partly because of communal polarisation of the legal system.[63] The British administration threatened penalties for the worst cases of official negligence, however, these threats carried little weight owing to impending British withdrawal from the region.[74] Statements by the Muslim League were seen to be of more consequence; one prominent politician of the League offered protection for perpetrators and threatened action against such officials who maintained law and order, in the Attock district.[74] This established a precedent of impunity for officials and policemen acting in a biased manner.[63] Such failures to prosecute the perpetrators are seen to have enabled the later violence in Punjab, closer to the partition.[75]

Legacy[edit]

The events have produced some of the most unforgettable images of the partition violence.[5] Those who died in the violence, especially those who killed themselves or were killed by their families to prevent anticipated conversion, rapes, abductions or forced marriages—which were seen as violative of community honour—were valorised for their sacrifice and continue to be seen as martyrs in the Sikh community.[76][k][l]

Cultural depictions[edit]

Images of the aftermath of the massacres were compiled by politician Prabodh Chandra and published in a booklet titled Rape of Rawalpindi in 1947, soon after the massacres. The circulation of this booklet was stopped by the government fearing retaliation against Muslims in East Punjab.[58][m] The events, in particular the massacre and mass suicide at Thoha Khalsa, were depicted in the 1988 television film Tamas, directed by Govind Nihalani. The film was based on Bhisham Sahni's Hindi novel of the same name.[79][n] An incident similar to the Thoha Khalsa mass suicide is also depicted in the 2003 film Khamosh Pani.[81] A Punjabi novel based on the events called Khoon de Sohille written by Nanak Singh was published in 1948. It was translated into English as Hymns in Blood (2022).[82] Other works based on the violence include Kartar Singh Duggal’s 1951 Punjabi novel Nahun te maas (translated into English as Twice Born Twice Dead in 1979) and Shauna Singh Baldwin’s 1999 English novel What the Body Remembers.[83]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The earliest use of this term comes from an eponymous 1947 booklet containing images from the massacres, compiled and published soon after the massacres.[10][11]

- ^ Bertrand Glancy, the governor of the province at the time, estimated that the League had the support of only 80 members overall.[12]

- ^ The coalition ministry claimed to have the support of 94 members in total.[13]

- ^ The Punjab province is said to have remained unaffected by such violence due to the coalition government in place.[16]

- ^ Much of this increased hostility is blamed on the League’s communal election campaign and later agitations in Punjab.[23]

- ^ Some mobs had also come from neighbouring Hazara.[32]

- ^ Muslims comprised close to 75% of the police force in the Punjab province as a whole.[53]

- ^ Political Scientist Ishtiaq Ahmed notes that Jinnah had issued strong condemnations for killings of Muslims in Bihar a few months earlier, but never did so for the Rawalpindi massacres.[54]

- ^ Attacks continued till 13 March, while at some places they continued till 15 March.

- ^ This figure was mentioned in a note by the Home Secretary to Punjab Government in July 1947. The number of Muslim deaths stood at 38 according to it.[57]

- ^ An early example of this was when an April 1947 report in The Statesman compared the Thoha Khalsa mass suicide with the Rajput tradition of jauhar (self-immolation by women and children to avoid rape or enslavement by invaders in the face of defeat in a war).[77]

- ^ Many of those who remember the victims as martyrs are themselves survivors of the massacres, or descendants of survivors.

- ^ Historian Yasmin Khan states that the booklet contained one-sided and inflammatory commentary.[78]

- ^ Sahni had visited Thoha Khalsa in the aftermath of the massacres.[80]

References[edit]

- ^ Ahmed 2011, p. 685.

- ^ Hajari 2015, p. 108.

- ^ Ahmed 2011, pp. 221, 374.

- ^ Butalia 2000, p. 183.

- ^ a b c d Pandey 2001, p. 24.

- ^ Talbot 2019, p. 10.

- ^ Talbot & Singh 2009, p. 67.

- ^ Major 1995, p. 59.

- ^ Butalia 2013, p. 73.

- ^ Chandra, Prabodh Rape of Rawalpindi (1947)

- ^ Ahmed 2011, p. 221.

- ^ Ahmed 2022, p. 113.

- ^ Talbot 2013, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Talbot 2013, p. 148.

- ^ Brass 2003, p. 76.

- ^ a b Talbot & Singh 2009, p. 178.

- ^ a b c Pandey 2001, p. 23.

- ^ Hajari 2015, p. 88.

- ^ Ahmed 2022, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Ahmed 2019, p. 52.

- ^ Hajari 2015, pp. 97–99.

- ^ Talbot & Singh 2009, pp. 74–75.

- ^ a b Talbot 2013, p. 161.

- ^ Hajari 2015, pp. 103-104: "A crowd of Leaguers had gathered outside [the Punjab Assembly] to heckle the Hindu and Sikh politicians, shouting “Quaid-i-Azam Zindabad!” and “Pakistan Zindabad!” Tara Singh whipped his kirpan out of his scabbard and waved it above his head. “Pakistan Murdabad!” he roared. Death to Pakistan!".

- ^ Khan 2017, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Ahmed 2011, p. 207.

- ^ Hajari 2015, p. 104.

- ^ a b Chatterjee, Chanda (1998). "Muslim League Direct Action and Popular Reaction in the Punjab: The Multan and Rawalpindi Riots, March 1947". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 59: 834–43. JSTOR 44147056. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ Ahmed 2019, p. 53.

- ^ Ahmed 2019, p. 23.

- ^ Ahmed 2011, pp. 239–240.

- ^ Ahmed 2011, p. 212.

- ^ Ahmed 2022, p. 219.

- ^ Ahmed 2011, p. 223.

- ^ Butalia 2013, p. 45.

- ^ Hajari 2015, p. 111.

- ^ a b Singh, Ajmer. "The March Massacre in Pothohar". The Tribune. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ Ahmed 2022, pp. 223–231.

- ^ Pandey 2002, p. 173.

- ^ Pandey 2002, pp. 172, 175.

- ^ Pandey 2002, p. 177.

- ^ a b Talbot 2009, p. 47.

- ^ Ahmed 2011, p. 238.

- ^ Talbot & Singh 2009, p. 85.

- ^ Pandey 2002, p. 172.

- ^ a b Hajari 2015, p. 108

- ^ Khosla 1989, p.107: "On March 6 meetings were held in the village mosques and the Muslims were told that the Jumma Masjid at Rawalpindi had been razed to the ground by Hindus and Sikhs and that the city streets were littered with Muslim corpses. The audience was exhorted to avenge these wrongs.".

- ^ Abid, Abdul Majeed (29 December 2014). "The forgotten massacre". The Nation. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Pandey 2002, p. 171.

- ^ a b Hajari 2015, p. 109

- ^ Ahmed 2022, p. 240.

- ^ Talbot & Singh 2009, p. 87.

- ^ Talbot & Singh 2009, p. 86.

- ^ a b Ahmed 2022, p. 685.

- ^ Ahmed 2022, p. 220.

- ^ Butalia 2013, p. 198.

- ^ a b c Khosla 1989, p. 112.

- ^ a b Ahmed 2022, p. 221.

- ^ Butalia 2000, p.183: "Here [in Sikh villages around Rawalpindi], during an 8 day period from 6 March to 13 March much of the Sikh population was killed (estimates suggest 4–5,000 dead), houses were decimated, gurudwaras destroyed..

- ^ Talbot 2019, p.4: "The attacks on largely defenceless minority populations have earcned the violence the title of the Rawalpindi Massacres. Outlying villages in the Rawalpindi district witnessed shocking violence against Sikh inhabitants. Around seven thousand to eight thousand people were estimated to have died.".

- ^ Butalia 2000, p. 187.

- ^ Ahmed 2019, p. 54.

- ^ a b c Talbot 2019, p. 5.

- ^ Chattha, Ilyas (2011), Partition and Locality: Violence, Migration and Development in Gujranwala and Sialkot, 1947–1961, Karachi: Oxford University Press, p. 161, ISBN 978-0-19-906172-3

- ^ Brass 2003, p. 88.

- ^ Hajari 2015, p. 157.

- ^ Ahmed 2022, pp. 65, 693.

- ^ Pandey 2001, p. 25.

- ^ Ahmed 2022, pp. 2, 220.

- ^ Talbot & Singh 2009, p. 138.

- ^ Butalia 2013, p. 91.

- ^ Ahmed 2022, p. 90.

- ^ Pandey 2002, pp. 174–175.

- ^ a b Talbot 2009, p. 48.

- ^ Talbot 2009, p. 52.

- ^ Butalia 2000, p. 189.

- ^ Butalia 2000, p. 190.

- ^ Khan 2017, p. 138.

- ^ Saint 2020, pp. 99–105.

- ^ Sahni, Bhisham; Singh, Pankaj K. (1995). "Making Connections". Indian Literature. 38 (3 (167)): 89–97. JSTOR 23335872. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Sharma, Manoj (2009). "Portrayal of Partition in Hindi cinema". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 70: 1155–60. JSTOR 44147759. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ Dutt, Nirupama (31 July 2022). "Hymns in Blood at Chakri village on River Soan". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ Saint 2020, pp. 151–155.

Bibliography[edit]

- Ahmed, Ishtiaq (2011), The Punjab Bloodied, Partitioned and Cleansed: Unravelling the 1947 Tragedy through Secret British Reports and First-Person Accounts, Rupa/OUP Pakistan, ISBN 978-93-5520-578-0, ISBN 978-0-19-906470-0

- Ahmed, Ishtiaq (2022), The Punjab: Bloodied, Partitioned and Cleansed, New Delhi: Rupa Publications, ISBN 978-93-5520-578-0

- Ahmed, Ishtiaq (2019), "The 1947 Partition of Punjab", in Ranjan, Amit (ed.), Partition of India: Postcolonial Legacies, Routledge, pp. 43–60, ISBN 978-1-138-08003-4

- Ahmed, Ishtiaq (2018), "The 1947 Partition of Punjab", in Ranjan, Amit (ed.), Partition of India: Postcolonial Legacies, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-138-08003-4

- Brass, Paul (2003), "The partition of India and retributive genocide in the Punjab,1946–47: means, methods, and purposes", Journal of Genocide Research, vol. 5, pp. 71–101, doi:10.1080/14623520305657, S2CID 14023723

- Butalia, Urvashi (1998). The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-027171-3.

- Butalia, Urvashi (2013), The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-140-27171-3

- Butalia, Urvashi (2000), "Community, State and Gender: Some Reflections on the Partition of India", in Hasan, Mushirul (ed.), Inventing Boundaries: Gender, Politics and the Partition of India, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, p. 183, ISBN 019-565103-0

- Hajari, Nisid (2015), Midnight's Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India's Partition, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 978-0-547-66924-3

- Khan, Yasmin (2007), The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-12078-3

- Khan, Yasmin (2017). The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-23032-1.

- Khosla, Gopal Das (1989), Stern Reckoning: A Survey of the Events leading up to and following the Partition of India, Delhi: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195624175, OCLC 22415680

- Major, Andrew (1995), "Abduction of women during the partition of the Punjab", South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 18 (1), doi:10.1080/00856409508723244

- Pandey, Gyanendra (2001), Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521807593

- Pandey, Gyanendra (2002). "The Long Life of Rumor". Alternatives: Global, Local, Political. 27 (2): 165–91. doi:10.1177/030437540202700203. JSTOR 40645044. S2CID 142067944. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- Saint, Tarun K. (2020) [2010], Witnessing Partition: Memory, History, Fiction (2nd ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-367-21036-6

- Talbot, Ian; Singh, Gurharpal (2009), The Partition of India, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-67256-6

- Talbot, Ian (2009). "Indo-Pak massacres". In Forsythe, David P. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Human Rights. Vol. 1. OUP USA. pp. 45–53. ISBN 978-0-19-533402-9.

- Talbot, Ian (2013) [1996], Khizr Tiwana, the Punjab Unionist Party and the Partition of India, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-700-70427-9

- Talbot, Ian (2019), "The 1947 Partition violence: Characteristics and interpretations", in Mohanram, Radhika; Raychaudhuri, Anindya (eds.), Partitions and Their Afterlives: Violence, Memories, Living, Rowman & Littlefield International, ISBN 9781783488407