Smoking cessation

| Part of a series on |

| Smoking |

|---|

Smoking cessation, usually called quitting smoking or stopping smoking, is the process of discontinuing tobacco smoking.[1] Tobacco smoke contains nicotine, which is addictive and can cause dependence.[2][3] As a result, nicotine withdrawal often makes the process of quitting difficult.

Smoking is the leading cause of preventable death and a global public health concern.[4] Tobacco use leads most commonly to diseases affecting the heart and lungs, with smoking being a major risk factor for heart attacks,[5][6] strokes,[7] chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),[8] idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF),[9] emphysema,[8] and various types and subtypes of cancers[10] (particularly lung cancer, cancers of the oropharynx,[11] larynx,[11] and mouth,[11] esophageal and pancreatic cancer).[12] Smoking cessation significantly reduces the risk of dying from smoking-related diseases.[13][14] The risk of heart attack in a smoker decreases by 50% after one year of cessation. Similarly, the risk of lung cancer decreases by 50% in 10 years of cessation [15]

From 2001 to 2010, about 70% of smokers in the United States expressed a desire to quit smoking, and 50% reported having attempted to do so in the past year.[16] Many strategies can be used for smoking cessation, including abruptly quitting without assistance ("cold turkey"), cutting down then quitting, behavioral counseling, and medications such as bupropion, cytisine, nicotine replacement therapy, or varenicline. In recent years, especially in Canada and the United Kingdom, many smokers have switched to using electronic cigarettes to quit smoking tobacco.[16][17][18] However, a 2022 study found that 20% of smokers who tried to use e-cigarettes to quit smoking succeeded but 66% of them ended as dual users of cigarettes and vape products one year out.[19]

Most smokers who try to quit do so without assistance. However, only 3–6% of quit attempts without assistance are successful long-term.[20] Behavioral counseling and medications each increase the rate of successfully quitting smoking, and a combination of behavioral counseling with a medication such as bupropion is more effective than either intervention alone.[21] A meta-analysis from 2018, conducted on 61 randomized controlled trials, showed that among people who quit smoking with a cessation medication (and some behavioral help), approximately 20% were still nonsmokers a year later, as compared to 12% who did not take medication.[22]

In nicotine-dependent smokers, quitting smoking can lead to nicotine withdrawal symptoms such as nicotine cravings, anxiety, irritability, depression, and weight gain.[23]: 2298 Professional smoking cessation support methods generally attempt to address nicotine withdrawal symptoms to help the person break free of nicotine addiction.

Smoking cessation methods

Unassisted

It often takes several attempts, and potentially utilizing different approaches each time, before achieving long-term abstinence. Over 74.7% of smokers attempt to quit without any assistance,[24] otherwise known as "cold turkey", or with home remedies. Previous smokers make between an estimated 6 to 30 attempts before successfully quitting.[25] Identifying which approach or technique is eventually most successful is difficult. It has been estimated, for example, that only about 4% to 7% of people are able to quit smoking on any given attempt without medicines or other help.[2][26] The majority of quit attempts are still unassisted, though the trend seems to be shifting.[27] In the U.S., for example, the rate of unassisted quitting fell from 91.8% in 1986 to 52.1% during 2006 to 2009.[27] The most frequent unassisted methods were "cold turkey",[27] a term that has been used to mean either unassisted quitting or abrupt quitting and "gradually decreased number" of cigarettes, or "cigarette reduction".[3]

Cold turkey

"Cold turkey" is a colloquial term indicating abrupt withdrawal from an addictive drug. In this context, it indicates sudden and complete cessation of all nicotine use. In three studies, it was the quitting method cited by 76%,[28] 85%,[29] or 88%[30] of long-term successful quitters. In a large British study of ex-smokers in the 1980s, before the advent of pharmacotherapy, 53% of the ex-smokers said that it was "not at all difficult" to stop, 27% said it was "fairly difficult", and the remaining 20% found it very difficult.[31] Studies have found that two-thirds of recent quitters reported using the cold turkey method and found it helpful.[32]

Cutting down to quit

Gradual reduction involves slowly reducing one's daily intake of nicotine. This method can theoretically be accomplished through repeated changes to cigarettes with lower nicotine levels, by gradually reducing the number of cigarettes smoked daily, or by smoking only a fraction of a cigarette on each occasion. A 2009 systematic review by researchers at the University of Birmingham found that gradual nicotine replacement therapy could be effective in smoking cessation.[33][34] There is no significant difference in quit rates between smokers who quit by gradual reduction or abrupt cessation as measured by abstinence from smoking of at least six months from the quit day. The same review also looked at five pharmacological aids for reduction. When reducing the number of smoked cigarettes, it found some evidence that additional varenicline or fast-acting nicotine replacement therapy can positively affect quitting for six months or longer.[33]

Medications

The American Cancer Society notes that "Studies in medical journals have reported that about 25% of smokers who use medicines can stay smoke-free for over 6 months."[34] Single medications include:

- Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT): Five medications have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to deliver nicotine in a form that does not involve the risks of smoking: transdermal nicotine patches, nicotine gum, nicotine lozenges, nicotine inhalers, nicotine oral sprays, and nicotine nasal sprays.[35] High-quality evidence indicates that these forms of NRT improve the success rate of people who attempt to stop smoking.[36] NRTs are meant to be used for a short period of time and should be tapered down to a low dose before stopping. NRTs increase the chance of stopping smoking by 50 to 60% compared to placebo or to no treatment.[35] Some reported side effects are local slight irritation (inhalers and sprays) and non-ischemic chest pain (rare).[35][37] Others include mouth soreness and dyspepsia (gum), nausea or heartburn (lozenges), as well as sleep disturbances, insomnia, and a local skin reaction (patches).[37][38] A study found that 93% of over-the-counter NRT users relapse and return to smoking within six months.[39] There is weak evidence that adding mecamylamine to nicotine is more effective than nicotine alone.[40]

- Antidepressants: The antidepressant bupropion is considered a first-line medication for smoking cessation and has been shown in many studies to increase long-term success rates. Although bupropion increases the risk of getting adverse events, there is no clear evidence that the drug has more or less adverse effects when compared to a placebo. Nortriptyline produces significant rates of abstinence versus placebo.[41] Other antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and St. John's wort have not been consistently shown to be effective for smoking cessation.[41]

- Varenicline decreases the urge to smoke and reduces withdrawal symptoms and is therefore considered a first-line medication for smoking cessation.[42] The number of people stopping smoking with varenicline is higher than with bupropion or NRT.[43] Varenicline more than doubled the chances of quitting compared to placebo, and was also as effective as combining two types of NRT. 2 mg/day of varenicline has been found to lead to the highest abstinence rate (33.2%) of any single therapy, while 1 mg/day leads to an abstinence rate of 25.4%. A 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials concluded there is no evidence supporting a connection between varenicline and increased cardiovascular events.[44] Concerns arose that varenicline may cause neuropsychiatric side effects, including suicidal thoughts and behavior.[43] However, more recent studies indicate less serious neuropsychiatric side effects. For example, a 2016 study involving 8,144 patients treated at 140 centers in 16 countries "did not show a significant increase in neuropsychiatric adverse events attributable to varenicline or bupropion relative to nicotine patch or placebo".[45] No link between depressed moods, agitation or suicidal thinking in smokers taking varenicline to decrease the urge to smoke has been identified.[43] For people who have pre-existing mental health difficulties, varenicline may slightly increase the risk of experiencing these neuropsychiatric adverse events.[43]

- Clonidine may reduce withdrawal symptoms and "approximately doubles abstinence rates when compared to a placebo," but its side effects include dry mouth and sedation, and abruptly stopping the drug can cause high blood pressure and other side effects.[46][47]

- There is no good evidence anxiolytics are helpful.[48]

- Previously, rimonabant, which is a cannabinoid receptor type 1 antagonist, was used to help in quitting and moderate the expected weight gain.[49] But it is important to know that the manufacturers of rimonabant and taranabant stopped production in 2008 due to serious CNS side effects.[49]

The 2008 US Guideline specifies that three combinations of medications are effective:[46]: 118–120

- Long-term nicotine patch and ad libitum NRT gum or spray

- Nicotine patch and nicotine inhaler

- Nicotine patch and bupropion (the only combination that the US FDA has approved for smoking cessation)

A meta-analysis from 2018, conducted on 61 RCTs, showed that during their first year of trying to quit, approximately 80% of the participants in the studies who got drug assistance (bupropion, NRT, or varenicline) returned to smoking, while 20% continued to not smoke for the entire year (i.e.: remained sustained abstinent).[22] In comparison, 12% the people who got placebo kept from smoking for (at least) an entire year.[22] This makes the net benefit of the drug treatment to be 8% after the first 12 months.[22] In other words, out of 100 people who will take medication, approximately 8 of them would remain non-smoking after one year thanks to the treatment.[22] During one year, the benefit from using smoking cessation medications (Bupropion, NRT, or varenicline) decreases from 17% in 3 months, to 12% in 6 months to 8% in 12 months.[22]

Community interventions

Community interventions using "multiple channels to provide reinforcement, support and norms for not smoking" may have an effect on smoking cessation outcomes among adults.[50] Specific methods used in the community to encourage smoking cessation among adults include:

- Policies making workplaces[28] and public places smoke-free. It is estimated that "comprehensive clean indoor laws" can increase smoking cessation rates by 12%–38%.[51] In 2008, the New York State of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services banned smoking by patients, staff, and volunteers at 1,300 addiction treatment centers.[52]

- Voluntary rules making homes smoke-free, which are thought to promote smoking cessation.[28][53]

- Initiatives to educate the public regarding the health effects of second-hand smoke,[54] including the significant dangers of secondhand smoke infiltration for residents of multi-unit housing.[55]

- Increasing the price of tobacco products, for example by taxation. The US Task Force on Community Preventive Services found "strong scientific evidence" that this is effective in increasing tobacco use cessation [56]: 28–30 It is estimated that an increase in price of 10% will increase smoking cessation rates by 3–5%.[51]

- Mass media campaigns. There is evidence to suggest that when combined with other types of interventions, mass media campaigns may be of benefit.[56]: 30–32 [57]

- Weak evidence suggests that imposing institutional level smoking bans in hospitals and prisons may reduce smoking rates and second hand smoke exposure.[58]

- Researchers explored whether an opportunistic stop smoking intervention (advice, a vape starter pack and a referral to stop smoking services), was effective for people attending the emergency department. At 6 months, more people who received the intervention had quit smoking compared with people who received advice only.[59][60]

Pharmacist Interventions

Pharmacist-led interventions have proven to be effective in helping smoking cessation attempts. Many systematic reviews have looked at the importance of pharmacist involvement. In Malaysia, their study looked at how pharmacist intervention in patients' overall healthcare showed improvements in screening early stages of disease.[61] This allowed for earlier treatment starts in smoking-caused COPD. In addition, pharmacists in Malaysia could prescribe NRT products, and when they led a smoking cessation service, it was more successful than other smoking cessation trials in Malaysia.[61] It was also shown that pharmacist counselling and NRT products were more effective in smoking cessation than using NRT alone.

In pharmacist-led smoking cessation services in Ethiopia, the study found statistically and clinically significant benefits favouring pharmacist intervention.[62] They found that structured care, and regular visits, easy accessibility to pharmacists helped more people trying to quit than without. However, the study concluded that more research should be done in the area as they found an unknown risk of bias in the studies included[62]

Another systematic review analyzed pharmacist intervention in smoking cessation and alcohol and weight interventions.[63] They found that evidence suggests that the longer the duration of pharmacist-led intervention, the more influential the attempt at quitting was[63] In addition, they found that community pharmacists were beneficial in delivering public health information. Pharmacists have a great reach in the community to help with smoking cessation and have proven to help with lifestyle modifications and proper NRT use.[63]

Digital interventions

- Interactive web-based and stand-alone computer programs and online communities assist participants in quitting. For example, "quit meters" keep track of statistics such as how long a person has remained abstinent.[64] Computerised and interactive tailored interventions may be promising,[46]: 93–94 however, the evidence base for such interventions is weak.[65][66][67]

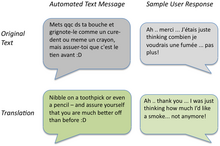

- A mobile phone-based intervention where automated, supportive text messages are sent alongside other forms of support helps more people quit smoking: "The current evidence supports a beneficial impact of mobile phone-based cessation interventions on six-month cessation outcomes."[68][69][70] A 2011 randomized trial of mobile phone-based smoking cessation support in the UK found that a Txt2Stop cessation program significantly improved cessation rates at six months.[71] A 2013 meta-analysis also noted "modest benefits" of mobile health interventions.[72]

- Interactive web-based programs combined with a Mobile phone: Two RCTs documented long-term treatment effects (abstinence rate: 20-22%) of such interventions.[73][74]

Psychosocial approaches

- The Great American Smokeout is an annual event that invites smokers to quit for one day, hoping they will be able to extend this forever.

- The World Health Organization's World No Tobacco Day is held on May 31 each year.

- Smoking-cessation support is often offered over the telephone quitlines[75][76] (e.g., the US toll-free number 1-800-QUIT-NOW), or in person. Three meta-analyses have concluded that telephone cessation support is effective when compared with minimal or no counselling or self-help and that telephone cessation support with medication is more effective than medication alone,[46]: 91–92 [56]: 40–42 and that intensive individual counselling is more effective than the brief personal counselling intervention.[77] A slight tendency towards better results for more intensive counselling was also observed in another meta-analysis. This analysis distinguished between reactive (smokers calling quitlines) and proactive (smokers receiving calls) interventions. For people who called the quitline themselves, additional calls helped to quit smoking for six months or longer. When proactively initiating contact with a smoker, telephone counselling increased the chances of smoking cessation by 2–4% compared with people who received no calls.[78] There is about 10% to 25% increase in the chance of smoking cessation success with more behavioral support provided in person or via telephone when used as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy.[79]

- Online social cessation networks attempt to emulate offline group cessation models using purpose built web applications. They are designed to promote online social support and encouragement for smokers when (usually automatically calculated) milestones are reached. Early studies have shown social cessation to be especially effective with smokers aged 19–29.[80]

- Group or individual psychological support can help people who want to quit. Recently, group therapy has been more helpful than self-help and some other individual intervention.[81] The psychological support form of counselling can be effective alone; combining it with medication is more effective, and the number of support sessions with medication correlates with effectiveness.[46]: 89–90, 101–103 [81][77] The counselling styles that have been effective in smoking cessation activities include motivational interviewing,[82][83][84] cognitive behavioral therapy[85] and acceptance and commitment therapy,[86] methods based on cognitive behavioral therapy.

- The Freedom From Smoking group clinic includes eight sessions and features a step-by-step plan for quitting smoking. Each session is designed to help smokers gain control over their behavior. The clinic format encourages participants to work on the process and problems of quitting both individually and as part of a group.[87]

- Multiple formats of psychosocial interventions increase quit rates: 10.8% for no intervention, 15.1% for one format, 18.5% for 2 formats, and 23.2% for three or four formats.[46]: 91

- The transtheoretical model, including "stages of change", has been used in tailoring smoking cessation methods to individuals,[88][89][90][91] however, there is some evidence to suggest that "stage-based self-help interventions (expert systems and/or tailored materials) and individual counselling are neither more nor less effective than their non-stage-based equivalents."[92]

How to set a quit date

Most smoking cessation resources such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)[93] and The Mayo Clinic[94] encourage smokers to create a quit plan, including setting a quit date, which helps them anticipate and plan for smoking challenges. A quit plan can improve a smoker's chance of a successful quit[95][96][97] as can setting Monday, as the quit date, given that research has shown that Monday more than any other day is when smokers are seeking information online to quit smoking[98] and calling state quitlines.[99] In Nepal, smokers are not selfish, a health campaign of two weeks is started on the occasion of Valentine day and Vasant panchami to motiviate individuals to quit smoking as a sacrifice for their loved ones and making it a meaningful decision of life. This campaign is taking public attention. [100]

Self-help

Self-help materials may produce a small increase in quit rates specially when there is no other supporting intervention form.[101] "The effect of self-help was weak", and the number of types of self-help did not produce higher abstinence rates.[46]: 89–91 Nevertheless, self-help modalities for smoking cessation include:

- In-person self-help groups such as Nicotine Anonymous,[102][103] or web-based cessation resources such as Smokefree.gov, which offers various types of assistance including self-help materials.[104]

- WebMD: a resource providing health information, tools for managing health, and support.[105]

- Self-help books such as Allen Carr's Easy Way to Stop Smoking.[106]

- Spirituality: In one survey of adult smokers, 88% reported a history of spiritual practice or belief, and of those more than three-quarters were of the opinion that using spiritual resources may help them quit smoking.[107]

- A review of mindfulness training as a treatment for addiction showed reduction in craving and smoking following training.[108]

- Physical activities help in the maintenance of smoking cessation even if there is no conclusive evidence of the most appropriate exercise intensity.[109]

Biochemical feedback

Various methods allow a smoker to see the impact of their tobacco use and the immediate effects of quitting. Using biochemical feedback methods can allow tobacco users to be identified and assessed, and monitoring throughout an effort to quit can increase motivation to quit.[110][111] Evidence-wise, little is known about the effects of using biomechanical tests to determine a person's risk related to smoking cessation.[112]

- Breath carbon monoxide (CO) monitoring: carbon monoxide is a significant component of cigarette smoke, and a breath carbon monoxide monitor can be used to detect current cigarette use. Carbon monoxide concentration in breath is directly correlated with the CO concentration in blood, known as percent carboxyhemoglobin. The value of demonstrating blood CO concentration to a smoker through a non-invasive breath sample is that it links the smoking habit with the physiological harm associated with smoking.[113] CO concentrations show a noticeable decrease within hours of quitting, which can encourage someone to work on quitting. Breath CO monitoring has been utilized in smoking cessation as a tool to provide patients with biomarker feedback, similar to how other diagnostic tools such as the stethoscope, the blood pressure cuff, and the cholesterol test have been used by treatment professionals in medicine.[110]

- Cotinine: Cotinine, a metabolite of nicotine, is present in smokers. Like carbon monoxide, a cotinine test can be a reliable biomarker to determine smoking status.[114] Cotinine levels can be tested through urine, saliva, blood, or hair samples. One of the main concerns of cotinine testing is the invasiveness of typical sampling methods.

While both measures offer high sensitivity and specificity, they differ in usage method and cost. For example, breath CO monitoring is non-invasive, while cotinine testing relies on bodily fluid. For instance, these two methods can be used alone or together when abstinence verification needs additional confirmation.[115]

Competitions and incentives

Financial or material incentives to entice people to quit smoking improve smoking cessation while the motivation is in place.[116] Competitions that require participants to deposit their own money, "betting" that they will succeed in quitting smoking, appear to be an effective incentive.[116] However, it is more difficult to recruit participants for this type of contest in head-to-head comparisons with other incentive models, such as giving participants NRT or placing them in a more typical rewards program.[117] Evidence shows that incentive programs may be effective for pregnant mothers who smoke.[116] As of 2019, there is an insufficient number of studies on "quit and win," and other competition-based interventions and results from the existing studies were inconclusive.[118]

Workplace incentives

A 2008 Cochrane review of smoking cessation activities in work-places concluded that "interventions directed towards individual smokers increase the likelihood of quitting smoking".[119] A 2010 systematic review determined that worksite incentives and competitions needed to be combined with additional interventions to produce significant increases in smoking cessation rates.[120]

Healthcare systems

Interventions delivered via healthcare providers and healthcare systems have been shown to improve smoking cessation among people who visit those services.

- A clinic screening system (e.g., computer prompts) to identify whether or not a person smokes doubled abstinence rates, from 3.1% to 6.4%.[46]: 78–79 Similarly, the Task Force on Community Preventive Services determined that provider reminders alone or with provider education effectively promote smoking cessation.[56]: 33–38

- A 2008 Guideline meta-analysis estimated that physician advice to quit smoking led to a quit rate of 10.2%, as opposed to a quit rate of 7.9% among patients who did not receive physician advice to quit smoking.[46]: 82–83 Even brief advice from physicians may have "a small effect on cessation rates",[121] and there is evidence that the physicians' probability of giving smoking cessation advice declines with the person who smokes age.[122] There is evidence that only 81% of smokers age 50 or greater received advice on quitting from their physicians in the preceding year.[123]

- For one-to-one or person-to-person counselling sessions, the duration of each session, the total contact time, and the number of sessions all correlated with the effectiveness of smoking cessation. For example, "Higher intensity" interventions (>10 minutes) produced a quit rate of 22.1% as opposed to 10.9% for "no contact" over 300 minutes of contact time made a quit rate of 25.5% as opposed to 11.0% for "no minutes" and more than 8 sessions produced a quit rate of 24.7% as opposed to 12.4% for 0–1 sessions.[46]: 83–86

- Both physicians and non-physicians increased abstinence rates compared with self-help or no clinicians.[46]: 87–88 For example, a Cochrane review of 58 studies found that nursing interventions increased the likelihood of quitting.[124] Another review found some positive effects when trained community pharmacists support patients in their smoking cessation trials.[125]

- Dental professionals also provide a key component in increasing tobacco abstinence rates in the community through counseling patients on the effects of tobacco on oral health in conjunction with an oral exam.[126]

- According to the 2008 Guideline, based on two studies the training of clinicians in smoking cessation methods may increase abstinence rates;[46]: 130 however, a Cochrane review found and measured that such training decreased smoking in patients.[127]

- Reducing or eliminating the costs of cessation therapies for smokers increased quit rates in three meta-analyses.[46]: 139–140 [56]: 38–40 [128]

- In one systematic review and meta-analysis, multi-component interventions increased quit rates in primary care settings.[129] "Multi-component" interventions were defined as those that combined two or more of the following strategies known as the "5 A's":[46]: 38–43

- Ask — Systematically identify all tobacco users at every visit

- Advise — Strongly urge all tobacco users to quit

Breath CO monitor displaying carbon monoxide concentration of an exhaled breath sample (in ppm) with its corresponding percent concentration of carboxyhemoglobin - Assess — Determine willingness to make a quit attempt

- Assist — Aid the patient in quitting (provide counselling-style support and medication)

- Arrange — Ensure follow-up contact

Substitutes for cigarettes

- Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is the general term for using products that contain nicotine but not tobacco to aid smoking cessation. These include nicotine lozenges, nicotine gum and inhalers, nicotine patches, and electronic cigarettes. In a review of 136 NRT-related Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group studies, substantial evidence supported NRT use in increasing the chances of successfully quitting smoking by 50 to 60% in comparison to placebo or a non-NRT control group.[130]

- Electronic cigarettes (ECs): There is high‐certainty evidence that ECs with nicotine increase quit rates compared to NRT and moderate‐certainty evidence that they increase quit rates compared to ECs without nicotine.[131][needs update] Little is known regarding the long-term harms related to vaping.[132] A 2016 UK Royal College of Physicians report supports using e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation tool.[133] A 2015 Public Health England report stated that "Smokers who have tried other methods of quitting without success could be encouraged to try e-cigarettes (EC) to stop smoking and stop smoking services should support smokers using EC to quit by offering them behavioural support."[134] However, since little is known about long term effects, other regulated options such as nicotine replacement therapy, varenicline or bupropion should be discussed primarily.

Alternative approaches

It is important to note that most of the alternative approaches below have minimal evidence to support their use, and their efficacy and safety should be discussed with a healthcare professional before starting.

- Acupuncture: Acupuncture has been explored as an adjunct treatment method for smoking cessation.[136] A 2014 Cochrane review was unable to make conclusions regarding acupuncture as the evidence is poor.[137] A 2008 guideline found no difference between acupuncture and placebo, found no scientific studies supporting laser therapy based on acupuncture principles but without the needles.[46]: 99

- Hypnosis: Hypnosis often involves the hypnotherapist suggesting the unpleasant outcomes of smoking to the patient.[138] Clinical trials studying hypnosis and hypnotherapy as a method for smoking cessation have been inconclusive.[46]: 100 [139][140][141] A Cochrane review was unable to find evidence of benefit of hypnosis in smoking cessation, and suggested if there is a beneficial effect, it is small at best.[139] However, a randomized trial published in 2008 found that hypnosis and nicotine patches "compares favorably" with standard behavioral counseling and nicotine patches in 12-month quit rates.[142]

- Herbal medicine: Many herbs have been studied as a method for smoking cessation, including lobelia and St John's wort.[143][144] The results are inconclusive, but St. Johns Wort shows few adverse events, but is a contraindication to many medications. Lobelia has been used to treat respiratory diseases like asthma and bronchitis, and has been used for smoking cessation because of chemical similarities to tobacco; lobelia is now listed in the FDA's Poisonous Plant Database.[145] Lobelia can still be found in many products sold for smoking cessation and should be used with caution. Herbal products should be discussed with healthcare professionals before use to confirm safety with other medications.

- Smokeless tobacco: There is little smoking in Sweden, which is reflected in the very low cancer rates for Swedish men. Use of snus (a form of steam-pasteurized, rather than heat-pasteurized, air-cured smokeless tobacco) is an observed cessation method for Swedish men and even recommended by some Swedish doctors.[146] However, the report by the Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (SCENIHR) concludes "STP (smokeless tobacco products) are addictive and their use is hazardous to health. Evidence on the effectiveness of STP as a smoking cessation aid is insufficient."[147] A recent national study on the use of alternative tobacco products, including snus, did not show that these products promote cessation.[148]

- Aversion therapy: It is a method of treatment works by pairing the pleasurable stimulus of smoking with other unpleasant stimuli. A Cochrane review reported that there is insufficient evidence of its efficacy.[149]

- Nicotine vaccines: Nicotine vaccines (e.g., NicVAX and TA-NIC) work by reducing the amount of nicotine reaching the brain; however, this method of therapy needs more investigations to establish its role and determine its side effects.[150]

- Technology and machine learning: Research studies using machine learning or artificial intelligence tools to provide feedback and communication with those who are trying to quit smoking are increasing, yet the findings are so far inconclusive.[151][152][153]

- Psilocybin has been being investigated as a potential smoking cessation aid for several years. In 2021, Johns Hopkins Medicine has been awarded a grant from the National Institutes of Health to explore the potential impacts of psilocybin and talk therapy on tobacco addiction.[154]

Special populations

Children and adolescents

Methods used with children and adolescents include:

- Motivational enhancement[155]

- Psychological support[155]

- Youth anti-tobacco activities, including participation in sports

- School-based curricula, like life-skills training

- School-based nurse counseling sessions[156]

- Access reduction to tobacco

- Anti-tobacco media[157][158]

- Family communication

Cochrane reviews, mainly of studies combining motivational enhancement and psychological support, concluded that "complex approaches" for smoking cessation among young people show promise.[155][159] The 2008 US Guideline recommends counselling-style support for adolescent smokers on the basis of a meta-analysis of seven studies.[46]: 159–161 Neither the Cochrane review nor the 2008 Guideline recommend medications for adolescents who smoke.

Pregnant women

Smoking during pregnancy can cause adverse health effects in both the woman and the fetus. The 2008 US Guideline determined that "person-to-person psychosocial interventions" (typically including "intensive counseling") increased abstinence rates in pregnant women who smoke to 13.3%, compared with 7.6% in usual care.[46]: 165–167 Mothers who smoke during pregnancy have a greater tendency towards premature births. Their babies are often underdeveloped, have smaller organs, and weigh much less than the average baby weight. In addition, these babies have weaker immune systems, making them more susceptible to many diseases such as middle ear inflammations and asthmatic bronchitis, as well as metabolic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension, all of which can bring significant morbidity.[160] Additionally, a study published by American Academy of Pediatrics shows that smoking during pregnancy increases the chance of sudden unexpected infant death ((SUID) or (SIDS)).[161] There is also an increased chance that the child will be a smoker in adulthood. A systematic review showed that psychosocial interventions help women quit smoking in late pregnancy and can reduce the incidence of low birth weight infants.[162]

It is a myth that a female smoker can cause harm to a fetus by quitting immediately upon discovering she is pregnant. This idea is not based on any medical study or fact.[163]

In a UK study that included 1140 pregnant women, e-cigarettes were found to be as effective as nicotine patches at helping pregnant women to quit smoking. The safety of the two products was also similar.[164][165] However, life style modification are the preferred method for pregnant women, and they should discuss smoking cessation techniques with a healthcare professional.

Schizophrenia

Studies across 20 countries show a strong association between patients with schizophrenia and smoking. People with schizophrenia are much more likely to smoke than those without the disease.[166] For example, in the United States, 80% or more of people with schizophrenia smoke, compared to 20% of the general population in 2006.[167]

Hospitalized smokers

Smokers who are hospitalised may be particularly motivated to quit.[46]: 149–150 A 2012 Cochrane review found that interventions beginning during a hospital stay and continuing for one month or more after discharge were effective in producing abstinence.[169]

Patients undergoing elective surgery may get benefits of preoperative smoking cessation interventions, when starting 4–8 weeks before surgery with weekly counseling for behavioral support and use of nicotine replacement therapy.[170] It is found to reduce the complications and the number of postoperative morbidity.[170]

Mood disorders

People with mood disorders or attention deficit hyperactivity disorders have a greater chance to begin smoking and a lower chance of quitting smoking.[171] A higher correlation with smoking has also been seen in people diagnosed with the major depressive disorder at any time throughout their lifetime compared to those without it. Success rates in quitting smoking were lower for those with a major depressive disorder diagnosis versus people without the diagnosis.[172] Exposure to cigarette smoke early on in life, during pregnancy, infancy, or adolescence, may negatively impact a child's neurodevelopment and increase the risk of developing anxiety disorders in the future.[171]

Homeless and poverty

Homelessness doubles the likelihood of an individual currently being a smoker. Homelessness is independent of other socioeconomic factors and behavioral health conditions. Homeless individuals have the same rates of desire to quit smoking. Still, they are less likely than the general population to attempt to stop successfully.[172][173]

In the United States, 60–80% of homeless adults are smokers. This is a considerably higher rate than the general adult population of 19%.[172] Many current smokers who are homeless report smoking as a means of coping with "all the pressure of being homeless."[172] The perception that homeless people smoking being "socially acceptable" can reinforce these trends.[172]

Americans under the poverty line have higher rates of smoking and lower rates of quitting than those over the poverty line.[173][174][175] While the homeless population is concerned about short-term effects of smoking, such as shortness of breath or recurrent bronchitis, they are not as concerned with long-term consequences.[174] The homeless population has unique barriers to quitting smoking, such as unstructured days, the stress of finding a job, and immediate survival needs that supersede the desire to quit smoking.[174]

These unique barriers can be combated through pharmacotherapy and behavioral counseling for high levels of nicotine dependence. The emphasis of immediate financial benefits to those who concern themselves with the short-term over the long-term, partnering with shelters to reduce the social acceptability of smoking in this population, and increased taxes on cigarettes and alternative tobacco products to further make the addiction more difficult to fund.[176]

Concurrent substance use disorders

Over three-quarters of people in treatment or recovery from substance misuse issues are current smokers.[177][178] Providing behavioural interventions (such as counseling and advice) and pharmacotherapy including nicotine replacement therapy (such as the use of patches or gum, varenicline, and/or bupropion) increase tobacco abstinence that is sustainable and also reduces the risk of returning to other substance use.[177][179][180][181]

Comparison of success rates

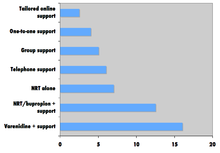

Comparison of success rates across interventions can be difficult because of different definitions of "success" across studies.[182] Robert West and Saul Shiffman, authorities in this field recognized by government health departments in a number of countries,[168]: 73, 76, 80 have concluded that, used together, "behavioral support" and "medication" can quadruple the chances that a quit attempt will be successful.

A 2008 systematic review in the European Journal of Cancer Prevention found that group behavioural therapy was the most effective intervention strategy for smoking cessation, followed by bupropion, intensive physician advice, nicotine replacement therapy, individual counselling, telephone counselling, nursing interventions, and tailored self-help interventions; the study did not discuss varenicline.[183]

Factors affecting success

Quitting can be harder for individuals with darkly pigmented skin than individuals with pale skin since nicotine has an affinity for melanin-containing tissues. Studies suggest this can cause the phenomenon of increased nicotine dependence and lower smoking cessation rate in darker-pigmented individuals.[185]

There is an important social component to smoking. The spread of smoking cessation from person to person contributes to the decrease in smoking among different populations or groups.[186] A 2008 study of a densely interconnected network of over 12,000 individuals found that smoking cessation by any given individual reduced the chances of others around them lighting up by the following amounts: a spouse by 67%, a sibling by 25%, a friend by 36%, and a coworker by 34%.[186] Nevertheless, a Cochrane review determined that interventions to increase social support for a smoker's cessation attempt did not improve long-term quit rates.[187]

Smokers trying to quit are faced with social influences that may persuade them to conform and continue smoking. Cravings are easier to detain when one's environment does not provoke the habit. Suppose a person who stopped smoking has close relationships with active smokers. In that case, they are often put into situations that make the urge to conform more tempting. However, in a small group with at least one other not smoking, the likelihood of conformity decreases. The social influence of smoking cigarettes has been proven to rely on simple variables. One researched variable depends on whether there is influence from a friend or non-friend.[188] The research shows that individuals are 77% more likely to conform to non-friends, while close friendships decrease conformity. Therefore, if an acquaintance offers a cigarette as a polite gesture, the person who has stopped smoking will be likelier to break his commitment than if a friend had suggested it. Recent research from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey of over 6,000 smokers found that smokers with fewer smoking friends were more likely to intend to quit and to succeed in their quit attempt.[188]

Expectations and attitude are significant factors. A self-perpetuating cycle occurs when a person feels bad for smoking yet smokes to alleviate feeling bad. Breaking that cycle can be a key in changing the sabotaging attitude.[189]

Smokers with major depressive disorder may be less successful at quitting smoking than non-depressed smokers.[46]: 81 [190]

Relapse (resuming smoking after quitting) has been related to psychological issues such as low self-efficacy,[191][192] or non-optimal coping responses;[193] however, psychological approaches to prevent relapse have not been proven to be successful.[194] In contrast, varenicline is suggested to have some effects and nicotine replacement therapy may help the unassisted abstainers.[194][195]

Side effects

| Craving for tobacco | 3 to 8 weeks[196] |

| Dizziness | Few days[196] |

| Insomnia | 1 to 2 weeks[196] |

| Headaches | 1 to 2 weeks[196] |

| Chest discomfort | 1 to 2 weeks[196] |

| Constipation | 1 to 2 weeks[196] |

| Irritability | 2 to 4 weeks[196] |

| Fatigue | 2 to 4 weeks[196] |

| Cough or nasal drip | Few weeks[196] |

| Lack of concentration | Few weeks[196] |

| Hunger | Up to several weeks[196] |

Withdrawal symptoms

The CDC recognizes seven common nicotine withdrawal symptoms that people often face when stopping smoking: "cravings to smoke, feeling irritated, grouchy, or upset, feeling jumpy and restless, having a hard time concentrating, having trouble sleeping, feeling hungry or gaining weight, or feeling anxious, sad or depressed."[197] Studies have shown that the use of pharmacotherapies, such as varenicline[198][199] can be useful in reducing withdrawal symptoms during the quitting process.

Weight gain

Giving up smoking is associated with an average weight gain of 4–5 kilograms (8.8–11.0 lb) after 12 months, most of which occurs within the first three months of quitting.[200]

The possible causes of the weight gain include:

- Smoking over-expresses the gene AZGP1 which stimulates lipolysis, so smoking cessation may decrease lipolysis.[201]

- Smoking suppresses appetite, which may be caused by nicotine's effect on central autonomic neurons (e.g., via regulation of melanin concentrating hormone neurons in the hypothalamus).[202] Smoking cessation will increase the persons appetite once again, especially as taste buds can return to its normal function.

- Heavy smokers are reported to burn 200 calories per day more than non-smokers eating the same diet.[203] Possible reasons for this phenomenon include nicotine's ability to increase energy metabolism or nicotine's effect on peripheral neurons.[202]

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services guideline suggests that sustained-release bupropion, nicotine gum, and nicotine lozenge be used "to delay weight gain after quitting."[204] There is not currently enough evidence to suggest one method of weight loss works better than others in preventing weight gain during the smoking cessation process.[205][206] It is helpful to reach for healthy snacks, such as celery and carrots, to aid in the increased appetite while also helping to limit weight gain. Regardless of post-cessation weight gain, there is a significant decrease in risk of cardiovascular disease in those who have quit smoking.[207] The risks of rebound weight gain is significantly less than the risks of continued smoking.

Mental health

Like other physically addictive drugs, nicotine addiction causes a down-regulation of the production of dopamine and other stimulatory neurotransmitters as the brain attempts to compensate for the artificial stimulation caused by smoking. Some studies from the 1990s found that when people stop smoking, depressive symptoms such as suicidal tendencies or actual depression may result,[190][208] although a recent international study comparing smokers who had stopped for 3 months with continuing smokers found that stopping smoking did not appear to increase anxiety or depression.[209] A 2021 review found that quitting smoking lessens anxiety and depression.[210]

A 2013 study by The British Journal of Psychiatry has found that smokers who successfully quit feel less anxious afterward, with the effect being greater among those who had mood and anxiety disorders than those who smoked for pleasure.[211]

Health benefits

Many of tobacco's detrimental health effects can be reduced or largely removed through smoking cessation. The health benefits over time of stopping smoking include:[213]

- Within 20 minutes after quitting, blood pressure and heart rate decrease

- Within a few days, carbon monoxide levels in the blood decrease to normal

- Within 48 hours, nerve endings and sense of smell and taste both start recovering

- Within 3 months, circulation and lung function improve

- Within 1 year, there are decreases in cough and shortness of breath

- Within 1–2 years, the risk of coronary heart disease is cut in half

- Within 5–10 years, the risk of stroke falls to the same as a non-smoker, and the risks of many cancers (mouth, throat, esophagus, bladder, cervix) decrease significantly

- Within 10 years, the risk of dying from lung cancer is cut in half, and the risks of larynx and pancreas cancers decrease

- Within 15 years, the risk of coronary heart disease drops to the level of a non-smoker; lowered risk for developing COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease)[213]

The British Doctors Study showed that those who stopped smoking before they reached 30 years old lived almost as long as those who never smoked.[212] Stopping in one's sixties can still add three years of healthy life.[212] Randomized U.S. and Canadian trials showed that a ten-week smoking cessation program decreased mortality from all causes over 14 years later.[214] A recent article on mortality in a cohort of 8,645 smokers who were followed up after 43 years determined that "current smoking and lifetime persistent smoking were associated with an increased risk of all-cause, CVD [cardiovascular disease], COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease], and any cancer, and lung cancer mortality."[215]

The significant increase in the risk of all-cause mortality that is present in people who smoke is decreased with long-term smoking cessation.[216] Smoking cessation can improve health status and quality of life at any age.[217] Evidence shows that cessation of smoking reduces risk of lung, laryngeal, oral cavity and pharynx, esophageal, pancreatic, bladder, stomach, colorectal, cervical, and kidney cancer, in addition to reducing the risk of acute myeloid leukemia.[217]

Another published study, "Smoking Cessation Reduces Postoperative Complications: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis," examined six randomized trials and 15 observational studies to examine preoperative smoking cessation's effects on postoperative complications. The findings were: 1) taken together, the studies demonstrated a decreased likelihood of postoperative complications in patients who ceased smoking before surgery; 2) overall, each week of cessation before surgery increased the magnitude of the effect by 19%. A significant positive effect was noted in trials where smoking cessation occurred at least four weeks before surgery; 3) For the six randomized trials, they demonstrated, on average, a relative risk reduction of 41% for postoperative complications.[218]

Cost-effectiveness

Cost-effectiveness analyses of smoking cessation activities have shown that they increase quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) at costs comparable with other types of interventions to treat and prevent disease.[46]: 134–137 Studies of the cost-effectiveness of smoking cessation include:

- In a 1997 U.S. analysis, the estimated cost per QALY varied by the type of cessation approach, ranging from group intensive counselling without nicotine replacement at $1108 per QALY to minimal counselling with nicotine gum at $4542 per QALY.[219]

- A study from Erasmus University Rotterdam limited to people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease found that the cost-effectiveness of minimal counselling, intensive counselling, and drug therapy were €16,900, €8,200, and €2,400 per QALY gained respectively.[220]

- Among National Health Service smoking cessation clients in Glasgow, pharmacy one-to-one counselling cost £2,600 per QALY gained and group support cost £4,800 per QALY gained.[221]

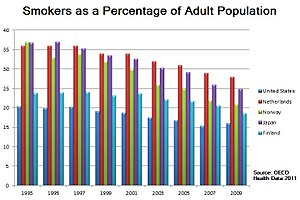

Statistical trends

The frequency of smoking cessation among smokers varies across countries. Smoking cessation increased in Spain between 1965 and 2000,[222] in Scotland between 1998 and 2007,[223] and in Italy after 2000.[224] In contrast, in the U.S. the cessation rate was "stable (or varied little)" between 1998 and 2008,[225] and in China smoking cessation rates declined between 1998 and 2003.[226]

Nevertheless, in a growing number of countries there are now more ex-smokers than smokers.[31] In the United States, 61.7% of adult smokers (55.0 million adults) who had ever smoked had quit by 2018, an increase from 51.7% in 2009.[227] As of 2020, the CDC reports that the number of adults who smoke in the U.S. has fallen to 30.8 million.[228]

See also

- Breath carbon monoxide monitor

- Bupropion

- Coerced abstinence

- Health effects of tobacco

- Health promotion

- Massachusetts Tobacco Cessation and Prevention Program

- Nicotine Anonymous

- Nicotine replacement therapy

- Smoking cessation programs in Canada

- Tobacco cessation clinics in India

- Tobacco control

- Tobacco Control (journal)

- Truth Initiative (formerly American Legacy Foundation)

- U.S. government and smoking cessation

- Vaping cessation

- Varenicline

- Youth Tobacco Cessation Collaborative

- World No Tobacco Day

Bibliography

- ^ "Take steps NOW to stop smoking". www.nhs.uk. London: National Health Service. 2022. Archived from the original on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ a b "How to Quit Smoking or Smokeless Tobacco". www.cancer.org. Atlanta, Georgia: American Cancer Society. 2022. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ a b Mooney ME, Johnson EO, Breslau N, Bierut LJ, Hatsukami DK (June 2011). Munafò M (ed.). "Cigarette smoking reduction and changes in nicotine dependence". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 13 (6). Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco: 426–430. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr019. LCCN 00244999. PMC 3103717. PMID 21367813. S2CID 29891495.

- ^ Kalkhoran S, Benowitz NL, Rigotti NA (August 2018). "Prevention and Treatment of Tobacco Use: JACC Health Promotion Series". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 72 (9). Elsevier for the American College of Cardiology: 1030–1045. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.036. PMC 6261256. PMID 30139432. S2CID 52077567.

- ^ Rodu B, Plurphanswat N (January 2021). "Mortality among male cigar and cigarette smokers in the USA" (PDF). Harm Reduction Journal. 18 (1). BioMed Central: 7. doi:10.1186/s12954-020-00446-4. LCCN 2004243422. PMC 7789747. PMID 33413424. S2CID 230800394. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Nonnemaker J, Rostron B, Hall P, MacMonegle A, Apelberg B (September 2014). Morabia A (ed.). "Mortality and economic costs from regular cigar use in the United States, 2010". American Journal of Public Health. 104 (9). American Public Health Association: e86–e91. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.301991. eISSN 1541-0048. PMC 4151956. PMID 25033140. S2CID 207276270.

- ^ Shah RS, Cole JW (July 2010). "Smoking and stroke: the more you smoke the more you stroke". Expert Review of Cardiovascular Therapy. 8 (7). Informa: 917–932. doi:10.1586/erc.10.56. PMC 2928253. PMID 20602553. S2CID 207215548.

- ^ a b Laniado-Laborín R (January 2009). "Smoking and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Parallel epidemics of the 21 century". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 6 (1). MDPI: 209–224. doi:10.3390/ijerph6010209. PMC 2672326. PMID 19440278. S2CID 19615031.

- ^ Oh CK, Murray LA, Molfino NA (February 2012). "Smoking and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis". Pulmonary Medicine. 2012. Hindawi Publishing Corporation: 808260. doi:10.1155/2012/808260. PMC 3289849. PMID 22448328. S2CID 14090263.

- ^ Shapiro JA, Jacobs EJ, Thun MJ (February 2000). Ganz PA N (ed.). "Cigar smoking in men and risk of death from tobacco-related cancers". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 92 (4). Oxford University Press: 333–337. doi:10.1093/jnci/92.4.333. eISSN 1460-2105. PMID 10675383. S2CID 7772405. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ a b c Anjum F, Zohaib J (4 December 2020). "Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma". Definitions (Updated ed.). Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. doi:10.32388/G6TG1L. PMID 33085415. S2CID 229252540. Bookshelf ID: NBK563268. Retrieved 7 February 2021 – via NCBI.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)[clarification needed] - ^ Chandrupatla SG, Tavares M, Natto ZS (July 2017). "Tobacco Use and Effects of Professional Advice on Smoking Cessation among Youth in India". Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 18 (7): 1861–1867. doi:10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.7.1861. PMC 5648391. PMID 28749122.

- ^ Temitayo Orisasami I, Ojo O (July 2016). "Evaluating the effectiveness of smoking cessation in the management of COPD". British Journal of Nursing. 25 (14): 786–791. doi:10.12968/bjon.2016.25.14.786. PMID 27467642.

- ^ "WHO Report on the global tobacco epidemic". World Health Organization. 2015. Archived from the original on July 8, 2015.

- ^ "Tobacco". www.who.int. Retrieved 2024-02-24.

- ^ a b "Vaping and quitting smoking". www.canada.ca. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 31 March 2022. Archived from the original on 8 May 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Using e-cigarettes to stop smoking". www.nhs.uk. London: National Health Service. 29 March 2022. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Wilson E, ed. (15 November 2019). "Long-term smokers who start vaping see health benefits within a month". New Scientist. London. ISSN 0262-4079. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Heiden BT, Baker TB, Smock N, Pham G, Chen J, Bierut LJ, et al. (2022). "Assessment of formal tobacco treatment and smoking cessation in dual users of cigarettes and e-cigarettes". Thorax. 78 (3): 267–273. doi:10.1136/thorax-2022-218680. PMC 9852353. PMID 35863765.

- ^ Rigotti NA (October 2012). "Strategies to help a smoker who is struggling to quit". JAMA. 308 (15): 1573–1580. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.13043. PMC 4562427. PMID 23073954.

- ^ Stead LF, Koilpillai P, Fanshawe TR, Lancaster T (March 2016). "Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (3): CD008286. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008286.pub3. PMC 10042551. PMID 27009521. S2CID 29033457.

- ^ a b c d e f Rosen LJ, Galili T, Kott J, Goodman M, Freedman LS (May 2018). "Diminishing benefit of smoking cessation medications during the first year: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Addiction. 113 (5). Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the Society for the Study of Addiction: 805–816. doi:10.1111/add.14134. PMC 5947828. PMID 29377409. S2CID 4764039.

- ^ Benowitz NL (June 2010). "Nicotine addiction". The New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (24): 2295–2303. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0809890. PMC 2928221. PMID 20554984.

- ^ Caraballo RS, Shafer PR, Patel D, Davis KC, McAfee TA (April 2017). "Quit Methods Used by US Adult Cigarette Smokers, 2014-2016". Preventing Chronic Disease. 14: E32. doi:10.5888/pcd14.160600. PMC 5392446. PMID 28409740.

- ^ Chaiton M, Diemert L, Cohen JE, Bondy SJ, Selby P, Philipneri A, et al. (June 2016). "Estimating the number of quit attempts it takes to quit smoking successfully in a longitudinal cohort of smokers". BMJ Open. 6 (6): e011045. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011045. PMC 4908897. PMID 27288378.

- ^ Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S (January 2004). "Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers". Addiction. 99 (1): 29–38. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x. PMID 14678060.

- ^ a b c Edwards SA, Bondy SJ, Callaghan RC, Mann RE (March 2014). "Prevalence of unassisted quit attempts in population-based studies: a systematic review of the literature". Addictive Behaviors. 39 (3): 512–519. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.036. PMID 24333037.

- ^ a b c Lee CW, Kahende J (August 2007). "Factors associated with successful smoking cessation in the United States, 2000". American Journal of Public Health. 97 (8): 1503–1509. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.083527. PMC 1931453. PMID 17600268.

- ^ Fiore MC, Novotny TE, Pierce JP, Giovino GA, Hatziandreu EJ, Newcomb PA, et al. (1990). "Methods used to quit smoking in the United States. Do cessation programs help?". JAMA. 263 (20): 2760–2765. doi:10.1001/jama.1990.03440200064024. PMID 2271019.

- ^ Doran CM, Valenti L, Robinson M, Britt H, Mattick RP (May 2006). "Smoking status of Australian general practice patients and their attempts to quit". Addictive Behaviors. 31 (5): 758–766. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.054. PMID 16137834.

- ^ a b Chapman S, MacKenzie R (February 2010). "The global research neglect of unassisted smoking cessation: causes and consequences". PLOS Medicine. 7 (2): e1000216. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000216. PMC 2817714. PMID 20161722.

- ^ Hung WT, Dunlop SM, Perez D, Cotter T (July 2011). "Use and perceived helpfulness of smoking cessation methods: results from a population survey of recent quitters". BMC Public Health. 11: 592. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-592. PMC 3160379. PMID 21791111.

- ^ a b Lindson N, Klemperer E, Hong B, Ordóñez-Mena JM, Aveyard P (September 2019). "Smoking reduction interventions for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (9): CD013183. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013183.pub2. PMC 6953262. PMID 31565800.

- ^ a b "Guide to quitting smoking. What do I need to know about quitting" (PDF). American Cancer Society. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-06-09. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ^ a b c Hartmann-Boyce J, Chepkin SC, Ye W, Bullen C, Lancaster T (May 2018). "Nicotine replacement therapy versus control for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5): CD000146. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub5. PMC 6353172. PMID 29852054.

- ^ Hartmann-Boyce J, Chepkin SC, Ye W, Bullen C, Lancaster T (May 2018). "Nicotine replacement therapy versus control for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5): CD000146. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub5. PMC 6353172. PMID 29852054.

- ^ a b Zhou HX (November 2008). "The debut of PMC Biophysics". PMC Biophysics. 1 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/1757-5036-1-1. PMC 2605105. PMID 19351423.

- ^ Henningfield JE, Fant RV, Buchhalter AR, Stitzer ML (2005). "Pharmacotherapy for nicotine dependence". CA. 55 (5): 281–99, quiz 322–3, 325. doi:10.3322/canjclin.55.5.281. PMID 16166074. S2CID 25668093.

- ^ Millstone K (2007-02-13). "Nixing the patch: Smokers quit cold turkey". Columbia.edu News Service. Archived from the original on 2018-12-25. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Lancaster T, Stead LF (2000). "Mecamylamine (a nicotine antagonist) for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1998 (2): CD001009. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001009. PMC 7271835. PMID 10796584.

- ^ a b Hajizadeh A, Howes S, Theodoulou A, Klemperer E, Hartmann-Boyce J, Livingstone-Banks J, et al. (2023-05-24). "Antidepressants for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (5): CD000031. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000031.pub6. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 10207863. PMID 37230961.

- ^ "Product monograph Champix" (PDF). Pfizer Canada. April 17, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-11-16.

- ^ a b c d Livingstone-Banks J, Fanshawe TR, Thomas KH, Theodoulou A, Hajizadeh A, Hartman L, et al. (2023-05-05). "Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (5): CD006103. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006103.pub8. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 10169257. PMID 37142273.

- ^ Sterling LH, Windle SB, Filion KB, Touma L, Eisenberg MJ (February 2016). "Varenicline and Adverse Cardiovascular Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". Journal of the American Heart Association. 5 (2): e002849. doi:10.1161/JAHA.115.002849. PMC 4802486. PMID 26903004.

- ^ Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, St Aubin L, McRae T, Lawrence D, et al. (June 2016). "Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial". Lancet. 387 (10037): 2507–2520. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)30272-0. PMID 27116918. S2CID 1611308.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB (2008). Clinical practice guideline: treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update (PDF). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. Archived from the original on 2016-03-27. Retrieved 2016-07-06.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Gourlay SG, Stead LF, Benowitz NL (2004). "Clonidine for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008 (3): CD000058. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000058.pub2. PMC 7038651. PMID 15266422.

- ^ Hughes JR, Stead LF, Lancaster T (2000). "Anxiolytics for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (4): CD002849. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002849. PMC 8407461. PMID 11034774.

- ^ a b Cahill K, Ussher MH (March 2011). "Cannabinoid type 1 receptor antagonists for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (3): CD005353. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005353.pub4. PMC 6486173. PMID 21412887.

- ^ Secker-Walker RH, Gnich W, Platt S, Lancaster T (2002). "Community interventions for reducing smoking among adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2002 (3): CD001745. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001745. PMC 6464950. PMID 12137631.

- ^ a b Lemmens V, Oenema A, Knut IK, Brug J (November 2008). "Effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions among adults: a systematic review of reviews" (PDF). European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 17 (6): 535–544. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282f75e48. PMID 18941375. S2CID 46131720. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-06.

- ^ "State-Mandated Tobacco Ban, Integration of Cessation Services, and Other Policies Reduce Smoking Among Patients and Staff at Substance Abuse Treatment Centers". Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2013-02-27. Retrieved 2013-05-13.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (May 2007). "State-specific prevalence of smoke-free home rules--United States, 1992-2003". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 56 (20): 501–504. PMID 17522588.

- ^ King BA, Dube SR, Homa DM (May 2013). "Smoke-free rules and secondhand smoke exposure in homes and vehicles among US adults, 2009-2010". Preventing Chronic Disease. 10: E79. doi:10.5888/pcd10.120218. PMC 3666976. PMID 23680508.

- ^ King BA, Babb SD, Tynan MA, Gerzoff RB (July 2013). "National and state estimates of secondhand smoke infiltration among U.S. multiunit housing residents". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 15 (7): 1316–1321. doi:10.1093/ntr/nts254. PMC 4571449. PMID 23248030.

- ^ a b c d e Hopkins DP, Briss PA, Ricard CJ, Husten CG, Carande-Kulis VG, Fielding JE, et al. (February 2001). "Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to reduce tobacco use and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 20 (2 Suppl): 16–66. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00297-X. PMID 11173215.

- ^ Bala MM, Strzeszynski L, Topor-Madry R (November 2017). "Mass media interventions for smoking cessation in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (11): CD004704. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004704.pub4. PMC 6486126. PMID 29159862.

- ^ Frazer K, McHugh J, Callinan JE, Kelleher C (May 2016). "Impact of institutional smoking bans on reducing harms and secondhand smoke exposure". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (5): CD011856. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011856.pub2. PMC 10164285. PMID 27230795.

- ^ Pope I, Clark LV, Clark A, Ward E, Belderson P, Stirling S, et al. (2024-05-01). "Cessation of Smoking Trial in the Emergency Department (COSTED): a multicentre randomised controlled trial". Emergency Medicine Journal. 41 (5): 276–282. doi:10.1136/emermed-2023-213824. ISSN 1472-0205. PMC 11041600. PMID 38531658.

- ^ "Stop smoking intervention in emergency departments helps people quit". NIHR Evidence. 15 October 2024.

- ^ a b Fai SC, Yen GK, Malik N (2016). "Quit rates at 6 months in a pharmacist-led smoking cessation service in Malaysia". Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada. 149 (5): 303–312. doi:10.1177/1715163516662894. ISSN 1715-1635. PMC 5032936. PMID 27708676.

- ^ a b Erku D, Hailemeskel B, Netere A, Belachew S (2019-01-09). "Pharmacist-led smoking cessation services in Ethiopia: Knowledge and skills gap analysis". Tobacco Induced Diseases. 17 (January): 01. doi:10.18332/tid/99573. ISSN 1617-9625. PMC 6751994. PMID 31582913.

- ^ a b c Brown TJ, Todd A, O'Malley C, Moore HJ, Husband AK, Bambra C, et al. (2016). "Community pharmacy-delivered interventions for public health priorities: a systematic review of interventions for alcohol reduction, smoking cessation and weight management, including meta-analysis for smoking cessation" (PDF). BMJ Open. 6 (2): e009828. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009828. ISSN 2044-6055. PMC 4780058. PMID 26928025.

- ^ Hendrick B. "Computer is an ally in quit-smoking fight". WebMD.

- ^ Myung SK, McDonnell DD, Kazinets G, Seo HG, Moskowitz JM (May 2009). "Effects of Web- and computer-based smoking cessation programs: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Archives of Internal Medicine. 169 (10): 929–937. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.109. PMID 19468084.

- ^ Taylor GM, Dalili MN, Semwal M, Civljak M, Sheikh A, Car J (September 2017). "Internet-based interventions for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (9): CD007078. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007078.pub5. PMC 6703145. PMID 28869775.

- ^ Hutton HE, Wilson LM, Apelberg BJ, Tang EA, Odelola O, Bass EB, et al. (April 2011). "A systematic review of randomized controlled trials: Web-based interventions for smoking cessation among adolescents, college students, and adults". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 13 (4): 227–238. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntq252. PMID 21350042.

- ^ Whittaker R, McRobbie H, Bullen C, Rodgers A, Gu Y (April 2016). "Mobile phone-based interventions for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (4): CD006611. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006611.pub4. PMC 6485940. PMID 27060875.

- ^ "Text messaging support helps smokers quit, but apps not yet shown to work". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 2020-02-12. doi:10.3310/signal-000876. S2CID 241974258.

- ^ "What is digital health technology and what can it do for me?". NIHR Evidence. 2022. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_53447. S2CID 252584020.

- ^ Free C, Knight R, Robertson S, Whittaker R, Edwards P, Zhou W, et al. (July 2011). "Smoking cessation support delivered via mobile phone text messaging (txt2stop): a single-blind, randomised trial". Lancet. 378 (9785): 49–55. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60701-0. PMC 3143315. PMID 21722952.

- ^ Free C, Phillips G, Watson L, Galli L, Felix L, Edwards P, et al. (2013). "The effectiveness of mobile-health technologies to improve health care service delivery processes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS Medicine. 10 (1): e1001363. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001363. PMC 3566926. PMID 23458994.

- ^ Brendryen H, Kraft P (March 2008). "Happy ending: a randomized controlled trial of a digital multi-media smoking cessation intervention". Addiction. 103 (3): 478–484, discussion 485–486. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02119.x. PMID 18269367. S2CID 4638860.

- ^ Brendryen H, Drozd F, Kraft P (November 2008). "A digital smoking cessation program delivered through internet and cell phone without nicotine replacement (happy ending): randomized controlled trial". Journal of Medical Internet Research. 10 (5): e51. doi:10.2196/jmir.1005. PMC 2630841. PMID 19087949.

- ^ Zhu SH, Anderson CM, Tedeschi GJ, Rosbrook B, Johnson CE, Byrd M, et al. (October 2002). "Evidence of real-world effectiveness of a telephone quitline for smokers". The New England Journal of Medicine. 347 (14): 1087–1093. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa020660. PMID 12362011.

- ^ Helgason AR, Tomson T, Lund KE, Galanti R, Ahnve S, Gilljam H (September 2004). "Factors related to abstinence in a telephone helpline for smoking cessation". European Journal of Public Health. 14 (3): 306–310. doi:10.1093/eurpub/14.3.306. PMID 15369039.

- ^ a b Lancaster T, Stead LF (March 2017). "Individual behavioural counselling for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (3): CD001292. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001292.pub3. PMC 6464359. PMID 28361496.

- ^ Matkin W, Ordóñez-Mena JM, Hartmann-Boyce J, et al. (Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group) (May 2019). "Telephone counselling for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (5): CD002850. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002850.pub4. PMC 6496404. PMID 31045250.

- ^ Hartmann-Boyce J, Hong B, Livingstone-Banks J, Wheat H, Fanshawe TR (June 2019). "Additional behavioural support as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (6): CD009670. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009670.pub4. PMC 6549450. PMID 31166007.

- ^ Baskerville NB, Azagba S, Norman C, McKeown K, Brown KS (March 2016). "Effect of a Digital Social Media Campaign on Young Adult Smoking Cessation". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 18 (3): 351–360. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntv119. PMID 26045252.

- ^ a b Stead LF, Carroll AJ, Lancaster T (March 2017). "Group behaviour therapy programmes for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (3): CD001007. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001007.pub3. PMC 6464070. PMID 28361497.

- ^ Lindson-Hawley N, Thompson TP, Begh R (March 2015). "Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD006936. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006936.pub3. PMID 25726920.

- ^ Hettema JE, Hendricks PS (December 2010). "Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation: a meta-analytic review". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 78 (6): 868–884. doi:10.1037/a0021498. PMID 21114344.

- ^ Heckman CJ, Egleston BL, Hofmann MT (October 2010). "Efficacy of motivational interviewing for smoking cessation: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Tobacco Control. 19 (5): 410–416. doi:10.1136/tc.2009.033175. PMC 2947553. PMID 20675688.

- ^ Perkins KA, Conklin CA, Levine MD (2008). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for smoking cessation: a practical guidebook to the most effective treatment. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-95463-1.

- ^ Ruiz FJ (2010). "A review of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) empirical evidence: Correlational, experimental psychopathology, component and outcome studies". International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. 10 (1): 125–162.

- ^ "About Freedom From Smoking". American Lung Association.

- ^ Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, DiClemente CC, Fava J (August 1988). "Measuring processes of change: applications to the cessation of smoking". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 56 (4): 520–528. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.56.4.520. PMID 3198809.

- ^ DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Fairhurst SK, Velicer WF, Velasquez MM, Rossi JS (April 1991). "The process of smoking cessation: an analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change" (PDF). Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 59 (2): 295–304. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.59.2.295. PMID 2030191. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS, Snow MG (January 1992). "Assessing outcome in smoking cessation studies". Psychological Bulletin. 111 (1): 23–41. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.23. PMID 1539088.

- ^ Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Velicer WF, Rossi JS (September 1993). "Standardized, individualized, interactive, and personalized self-help programs for smoking cessation" (PDF). Health Psychology. 12 (5): 399–405. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.12.5.399. PMID 8223364. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Cahill K, Lancaster T, Green N (November 2010). Cahill K (ed.). "Stage-based interventions for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD004492. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004492.pub4. PMID 21069681.

- ^ "Making a Quit Plan". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ "Preparing for Quit Day". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ Smit ES, Hoving C, Schelleman-Offermans K, West R, de Vries H (September 2014). "Predictors of successful and unsuccessful quit attempts among smokers motivated to quit". Addictive Behaviors. 39 (9): 1318–1324. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.04.017. PMID 24837754.

- ^ de Vries H, Eggers SM, Bolman C (April 2013). "The role of action planning and plan enactment for smoking cessation". BMC Public Health. 13: 393. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-393. PMC 3644281. PMID 23622256.

- ^ Bolman C, Eggers SM, van Osch L, Te Poel F, Candel M, de Vries H (Oct 2015). "Is Action Planning Helpful for Smoking Cessation? Assessing the Effects of Action Planning in a Web-Based Computer-Tailored Intervention". Substance Use & Misuse. 50 (10): 1249–1260. doi:10.3109/10826084.2014.977397. PMID 26440754. S2CID 20337590.

- ^ Ayers JW, Althouse BM, Johnson M, Cohen JE (January 2014). "Circaseptan (weekly) rhythms in smoking cessation considerations". JAMA Internal Medicine. 174 (1): 146–148. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11933. PMC 4670616. PMID 24166181.

- ^ Erbas B, Bui Q, Huggins R, Harper T, White V (February 2006). "Investigating the relation between placement of Quit antismoking advertisements and number of telephone calls to Quitline: a semiparametric modelling approach". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 60 (2): 180–182. doi:10.1136/jech.2005.038109. PMC 2566152. PMID 16415271.

- ^ "Dr Anil Om Murthi Archives". Enewspolar. Retrieved 2024-02-05.

- ^ Livingstone-Banks J, Ordóñez-Mena JM, Hartmann-Boyce J (January 2019). "Print-based self-help interventions for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD001118. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001118.pub4. PMC 7112723. PMID 30623970.

- ^ "Nicotine Anonymous offers help for those who desire to live free from nicotine". nicotine-anonymous.org.

- ^ Glasser I (February 2010). "Nicotine anonymous may benefit nicotine-dependent individuals". American Journal of Public Health. 100 (2): 196, author reply 196-196, author reply 197. doi:10.2105/ajph.2009.181545. PMC 2804638. PMID 20019295.

- ^ U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. "MySmokeFree: Your personalized quit experience". Smokefree.gov.

- ^ "Slideshow: 13 Best Quit-Smoking Tips Ever". WebMD.

- ^ Carr A (2004). The easy way to stop smoking. New York: Sterling. ISBN 978-1-4027-7163-7.

- ^ Gonzales D, Redtomahawk D, Pizacani B, Bjornson WG, Spradley J, Allen E, et al. (February 2007). "Support for spirituality in smoking cessation: results of pilot survey". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 9 (2): 299–303. doi:10.1080/14622200601078582. PMID 17365761.

- ^ Tang YY, Tang R, Posner MI (June 2016). "Mindfulness meditation improves emotion regulation and reduces drug abuse". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 163 (Suppl 1): S13–S18. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.041. PMID 27306725.

- ^ Ussher MH, Faulkner GE, Angus K, Hartmann-Boyce J, Taylor AH (October 2019). "Exercise interventions for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (10). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002295.pub6. PMC 6819982. PMID 31684691.