Biphobia

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| LGBTQ topics |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Bisexuality topics |

|---|

| Sexual identities |

| Studies |

| Attitudes, slang and discrimination |

| Community and literature |

| Lists |

| See also |

|

|

Biphobia is aversion toward bisexuality or people who are identified or perceived as being bisexual. Similarly to homophobia, it refers to hatred and prejudice specifically against those identified or perceived as being in the bisexual community. It can take the form of denial that bisexuality is a genuine sexual orientation, or of negative stereotypes about people who are bisexual (such as the beliefs that they are promiscuous or dishonest). Other forms of biphobia include bisexual erasure.[1] Biphobia may also avert towards other sexualities attracted to multiple genders such as pansexuality or polysexuality, as the idea of being attracted to multiple genders is generally the cause of stigma towards bisexuality.

The hatred of bisexual women and femmes, being a form of prejudice at the intersection of biphobia and misogyny, is referred to as bimisogyny[2][3][4][5] or less commonly bisexism.[6][7] This is a gendered form of biphobia that accounts for intersectionality in discussions on bigotry.

Etymology and usage

[edit]Biphobia is a blend word patterned on the term homophobia. It derives from the Latin prefix bi-(meaning "two, double") and the root -phobia (from the Greek: φόβος, phóbos, "fear") found in homophobia. Along with transphobia and homophobia, it is one of a family of terms used to describe intolerance and discrimination against LGBTQ people. The adjectival form biphobic describes things or qualities related to biphobia, and the less-common noun biphobe is a label for people thought to harbor biphobia.[8]

The term biphobia was first[9][10] introduced in 1992 by researcher Kathleen Bennett to mean "prejudice against bisexuality"[11] and "the denigration of bisexuality as a life-choice."[11] It has subsequently been defined as "any portrayal or discourse denigrating or criticizing men or women on the sole ground of their belonging to this [bisexual] socio-sexual identity, or refusing them the right to claim it."[12]

Biphobia need not be a phobia as defined in clinical psychology (i.e., an anxiety disorder). Its meaning and use typically parallel those of xenophobia.

Forms

[edit]Denial and erasure

[edit]Biphobia can lead people to deny that bisexuality is real, asserting that people who identify as bisexual are not genuinely bisexual, or that the phenomenon is far less common than they claim. One form of this denial is based on the heterosexist view that heterosexuality is the only true or natural sexual orientation. Thus anything that deviates from that is instead either a psychological pathology or an example of anti-social behavior.

Another form of denial stems from binary views of sexuality: that people are assumed monosexual, i.e. homosexual (gay/lesbian) or heterosexual (straight). Throughout the 1980s, modern research on sexuality was dominated by the idea that heterosexuality and homosexuality were the only legitimate orientations, dismissing bisexuality as "secondary homosexuality".[13] In that model, bisexuals are presumed to be either closeted lesbian/gay people wishing to appear heterosexual,[14] or individuals (of "either" orientation) experimenting with sexuality outside of their "normal" interest.[15] Maxims such as "people are either gay, straight, or lying" embody this dichotomous view of sexual orientation.[16]

Some people accept the theoretical existence of bisexuality but define it narrowly, as being only the equal sexual attraction towards both men and women.[16] Thus the many bisexual individuals with unequal attractions are instead categorized as either homosexual or heterosexual. Others acknowledge the existence of bisexuality in women, but deny that men can be bisexual.[17]

Some denial asserts that bisexual behavior or identity is merely a social trend – as exemplified by "bisexual chic" or gender bending – and not an intrinsic personality trait.[18] Same-gender sexual activity is dismissed as merely a substitute for sex with members of the opposite sex, or as a more accessible source of sexual gratification. Situational homosexuality in sex-segregated environments is presented as an example of this behavior.[19]

Biphobia is common from the heterosexual community, but is frequently exhibited by gay and lesbian people as well,[20] usually with the notion that bisexuals are able to escape oppression from heterosexuals by conforming to social expectations of opposite-gender sex and romance. This leaves some that identify as bisexual to be perceived as "not enough of either" or "not real".[21] An Australian study conducted by Roffee and Waling in 2016 established that bisexual people faced microaggressions, bullying, and other anti-social behaviors from people within the lesbian and gay community.[22]

Bisexual erasure (also referred to as bisexual invisibility) is a phenomenon that tends to omit, falsify, or re-explain evidence of bisexuality in history, academia, the news media, and other primary sources,[23][24] sometimes to the point of denying that bisexuality exists.[25][26]

Kenji Yoshino (2000) writes that there are three concepts that cause invisibility within bisexuality: "The three invisibilities can be seen as nested within each other; the first affects straights, gays, and bisexuals; the second affects only gays and bisexuals; and the third affects only bisexuals."[1] Forms of social standards and expectations, religion, and integrating the same-sex attraction aspect of bisexuality with homosexuality contribute to invisibility.[1]

Allegations that bisexual men are homophobic

[edit]One cause of biphobia in the gay male community is that there is an identity political tradition to assume that acceptance of male homosexuality is linked to the belief that men's sexuality is specialized. This causes many members of the gay male community to assume that the very idea that men can be bisexual is homophobic to gay men. A number of bisexual men feel that such attitudes force them to keep their bisexuality in the closet and that it is even more oppressive than traditional heteronormativity. These men argue that the gay male community has something to learn about respect for the individual from the lesbian community, in which there is not a strong tradition to assume links between notions about the origins of sexual preferences and the acceptance thereof. These views are also supported by some gay men who do not like anal sex (sides, as opposed to both tops and bottoms) and report that they feel bullied by other gay men's assumption that their dislike for anal sex is "homophobic" and want more respect for the individuality in which a gay man who does not hate himself may simply not like anal sex and instead prefer other sex acts such as mutual fellatio and mutual male masturbation.[27][28]

Claims of bisexuals adapting to heteronormativity

[edit]Some forms of prejudice against bisexuals are claims that bisexuality is an attempt in persecuted homosexuals to adapt to heteronormative societies by adopting a bisexual identity. Such claims are criticized by bisexuals and researchers studying the situation of bisexuals for falsely assuming that same-sex relationships would somehow escape persecution in heteronormative cultures by simply identifying as bisexual instead of homosexual. These researchers cite that all countries with laws against sex between people of the same sex give the same punishment regardless of what sexual orientation the people found guilty identify as, that any countries where same-sex marriage is illegal never allow marriages between people of the same sex no matter if they identify as bisexual instead of homosexual, and that laws against "gay" male blood donors invariably prohibit any man who had sex with other men from donating blood no matter if he identifies as homosexual or as bisexual. The conclusion made by these researchers is that since there is no societal benefit in identifying as bisexual instead of identifying as homosexual, the claim that bisexuals are homosexuals trying to adapt to a heteronormative society is simply false and biphobic and causes bisexuals to suffer a two-way discrimination from both LGBTQ society and heteronormative society that is worse than the one-way discrimination from heteronormative society that is faced by homosexuals. It is also argued that such two-way discrimination causes many bisexuals to hide their bisexuality to an even greater extent than homosexuals hide their sexuality, leading to underestimations of the prevalence of bisexuality especially in men for whom such assumptions of "really being completely gay" are the most rampant.[29][30]

In the book Bi: Notes for a Bisexual Revolution,[31] Shiri Eisner (2013) mentions Miguel Obradors-Campos' argument that bisexual individuals endure stigma by heterosexuals as well as gay and lesbian individuals. Eisner (2013) also writes, "some forms of biphobic stigma frequently observed in gay and lesbian communities: that bisexuals are privileged, that bisexuals will ultimately choose heterosexual relationships and lifestyles, that bisexual women are reinforcing patriarchy, that bisexuality is not a political identity, that bisexual women carry HIV to lesbian communities, and so on."[31]

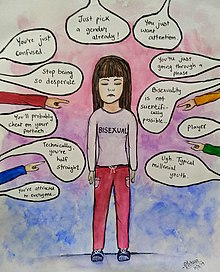

Negative stereotypes

[edit]Many stereotypes about people who identify as bisexual stem from denial or bisexual erasure. Because their orientation is not recognized as valid, they are stereotyped as confused, indecisive, insecure, experimenting, or "just going through a phase".[32]

The association of bisexuality with promiscuity stems from a variety of negative stereotypes targeting bisexuals as mentally or socially unstable people for whom sexual relations only with men, only with women, or only with one person at a time is not enough. These stereotypes may result from cultural assumptions that "men and women are so different that desire for one is an entirely different beast from desire for the other" ("a defining feature of heterosexism"), and that "verbalizing a sexual desire inevitably leads to attempts to satisfy that desire."[33]

As a result, bisexuals may bear a social stigma from accusations of cheating on or betraying their partners, leading a double life, being "on the down-low", and spreading sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV/AIDS. This presumed behavior is further generalized as dishonesty, secrecy, and deception. Bisexuals can be characterized as being "slutty", "easy", indiscriminate, and nymphomaniacs. Furthermore, they are strongly associated with polyamory, swinging, and polygamy,[34] the last being an established heterosexual tradition sanctioned by some religions and legal in several countries. This is despite the fact that bisexual people are as capable of monogamy or serial monogamy as homosexuals or heterosexuals.[35]

Tensions with pansexuals

[edit]Bisexuals frequently struggle with myths and misconceptions about the definition of bisexuality, such as the idea that bisexuality conforms to the gender binary (thereby excluding attraction to nonbinary individuals), or excludes attraction to trans people in general. This sometimes creates tension between bisexuals and pansexuals, as pansexuals often see themselves as being more inclusive to a wider array of genders.[36] A 2022 study by the Journal of Bisexuality suggested that the majority of women who identify as pansexual or queer defined bisexuality as limited to attraction to cisgender men and women and critiqued bisexuality as reinforcing the traditional gender binary. However, bisexual women defined bisexuality as attraction to two or more, or "similar or dissimilar" genders, described bisexuality as inclusive of attractions to all genders, and reported negative psychological outcomes as a result of the debate around bisexual gender inclusivity.[37]

A 2017 study published in the Journal of Bisexuality found that when bisexuals and pansexuals described gender and defined bisexuality, "there were no differences in how pansexual and bisexual people ... discussed sex or gender", and that the findings "do not support the stereotype that bisexual people endorse a binary view of gender while pansexual people do not."[38]

Effects

[edit]The mental and sexual health effects of biphobia on bisexual people are numerous. One study showed that bisexuals are often trapped in between the binaries of heterosexuality and homosexuality, creating a form of invalidation around their sexual identity. This often leads to recognized indicators of mental health issues such as low self-esteem and self-worth. These indicators and pressures to "choose" a sexual identity can, in many cases, lead to depression as they may feel they live in a culture that does not recognize their existence.[39]

While doing research on women at high-risk of HIV infection, one study, from the Journal of Bisexuality, concluded that bisexual women in the high-risk cohort studied were more likely to engage in various high risk behaviors and were at a higher risk of contracting HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.[40] These behaviors have been attributed to the unlikeliness of bisexuals discussing their sexuality and proper protection with health professionals for fear of judgement or discrimination, causing them to become undereducated on the issue(s).[41] In the book, Bi: Notes for a Bisexual Revolution,[31] Shiri Eisner (2013) discusses the suicidality statistics amongst bisexual identifying individuals as compared to heterosexuals, gays, and lesbians. Eisner (2013) referred to a Canadian study that found bisexual women had higher rates of suicidality as compared to heterosexual and lesbian women; the study also found that bisexual men also had increased rates of suicidality as compared to heterosexual and gay men[31]

Bisexual-identified people may face disparities in harsher degrees than their gay and lesbian peers. In the U.S. in particular, for example, they may face:

- Lower success rates for refugee applications; may also be the case in Canada and Australia[42]

- Higher levels of intimate partner violence[43]

- Higher likelihood of youth risk behavior amongst high school students[44]

- Higher likelihood of anxiety and mood disorders amongst bisexual women and men who report having sex with both sexes[45]

- Higher likelihood of living on less than $30,000 a year[46]

- Lower levels of reporting feeling "very accepted" in the workplace[46]

- Lower likelihood of being out to the important people in their lives[46]

- "Bisexuals report higher rates of hypertension, poor or fair physical health, smoking, and risky drinking than heterosexuals or lesbians/gays"[31]

- "Bisexual women in relationships with monosexual partners have an increased rate of domestic violence compared to women in other demographic categories"[31]

- "Many, if not most, bisexual people do not come out to their healthcare providers. This means they are getting incomplete information (for example, about safer sex practices)"[31]

- "Bisexual women were more likely to be current smokers and acute drinkers"[31]

- Higher risk of self harm, and suicidal ideation or attempts.[47]

- Feeling shame or discomfort with their sexual orientation or not feeling ready to be "out" to loved ones.

Intersectional perspectives

[edit]Intersections with feminism

[edit]Feminist positions on bisexuality range greatly, from acceptance of bisexuality as a feminist issue to rejection of bisexuality as a reactionary and anti-feminist backlash to lesbian feminism.[48]

A bisexual woman filed a lawsuit against the lesbian feminist magazine Common Lives/Lesbian Lives, alleging discrimination against bisexuals when her submission was not published.[49]

A widely studied example of lesbian-bisexual conflict within feminism was the Northampton Pride March during the years between 1989 and 1993, where many feminists involved debated over whether bisexuals should be included and whether or not bisexuality was compatible with feminism. Common lesbian-feminist critiques leveled at bisexuality were that bisexuality was anti-feminist, that bisexuality was a form of false consciousness, and that bisexual women who pursue relationships with men were "deluded and desperate". However, tensions between bisexual feminists and lesbian feminists have eased since the 1990s, as bisexual women have become more accepted within the feminist community.[50]

Nevertheless, some lesbian feminists such as Julie Bindel are still critical of bisexuality. Bindel has described female bisexuality as a "fashionable trend" being promoted due to "sexual hedonism" and broached the question of whether bisexuality even exists.[51] She has also made tongue-in-cheek comparisons of bisexuals to cat fanciers and devil worshippers.[52]

Lesbian feminist Sheila Jeffreys writes in The Lesbian Heresy (1993) that while many feminists are comfortable working alongside gay men, they are uncomfortable interacting with bisexual men. Jeffreys states that while gay men are unlikely to sexually harass women, bisexual men are just as likely to be bothersome to women as heterosexual men.[53]

Donna Haraway was the inspiration and genesis for cyberfeminism with her 1985 essay "A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century" which was reprinted in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (1991). Haraway's essay states that the cyborg "has no truck with bisexuality, pre-oedipal symbiosis, unalienated labor, or other seductions to organic wholeness through a final appropriation of all powers of the parts into a higher unity."[54]

The lipstick lesbian flag was introduced in 2010 by Natalie McCray, but has not been widely adopted;[55] some lesbians are against it because McCray's blog had biphobic (and racist and transphobic) comments, and because it does not include butch lesbians.[56]

Intersections with gender

[edit]Men

[edit]Studies indicate that preferences against dating bisexual men are stronger than against bisexual women, even amongst bisexual women.[57]

Intersections with race

[edit]While the general bisexual population as a whole faces biphobia, this oppression is also aggravated by other factors such as race. In a study conducted by Grady L. Garner Jr. titled Managing Heterosexism and Biphobia: A Revealing Black Bisexual Male Perspective, the author interviews 14 self-identified black bisexual men to examine how they cope with heterosexism and biphobia in order to formulate coping strategies. Data from the interviews revealed that 33% of the participants reported heterosexism and biphobia experiences, while 67% did not. He explains that the internalization of negative sociocultural messages, reactions, and attitudes can be incredibly distressing as bisexual black males attempted to translate or transform these negative experiences into positive bisexual identity sustaining ones.[58]

See also

[edit]- Media portrayals of bisexuality

- Bisexuality in the United States

- Bisexual community

- Heteronormativity

- History of bisexuality

- International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia (biphobia was added to the name of the day in 2015)

- List of phobias

- Victimization of bisexual women

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Yoshino, Kenji (2000). "The Epistemic Contract of Bisexual Erasure". Stanford Law Review. 52 (2): 353–461. doi:10.2307/1229482. JSTOR 1229482. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ Festival, Leeds LGBT+ Literature (2021-09-23). "Bimisogyny and What it Means". mysite. Retrieved 2022-12-28.

- ^ Pallotta-Chiarolli, Maria (2016-03-08). Women in Relationships with Bisexual Men: Bi Men By Women. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7391-3459-7.

- ^ Flood, Michael; Howson, Richard (2015-06-18). Engaging Men in Building Gender Equality. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-7895-1.

- ^ McAllum, Mary-Anne (2014-01-01). ""Bisexuality Is Just Semantics…": Young Bisexual Women's Experiences in New Zealand Secondary Schools". Journal of Bisexuality. 14 (1): 75–93. doi:10.1080/15299716.2014.872467. ISSN 1529-9716. S2CID 144498576.

- ^ Weiss, Jillian T. (2004-01-15). "GL vs. BT: The Archaeology of Biphobia and Transphobia within the U.S. Gay and Lesbian Community". Journal of Bisexuality. Rochester, NY. SSRN 1649428.

- ^ Sung, Mi Ra (2014-12-01). "Stress and Resilience: The Negative and Positive Aspects of Being an Asian American Lesbian or Bisexual Woman". Doctoral Dissertations.

- ^ Eliason, MJ (1997). "The prevalence and nature of biphobia in heterosexual undergraduate students". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 26 (3): 317–26. doi:10.1023/A:1024527032040. PMID 9146816. S2CID 30800831.

- ^ Monro, Surya (2015). Bisexuality: Identities, Politics, and Theories. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 23. ISBN 9781137007308.

- ^ Greenesmith, Heron (April 25, 2018). "We Know Biphobia Is Harmful. But Do We Know What's Behind It?". Rewire.News. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ a b Weise, Elizabeth Reba (1992). Closer to Home: Bisexuality and Feminism. Seattle: Seal Press. pp. 207. ISBN 1-878067-17-6.

- ^ Welzer-Lang, Daniel (October 11, 2008). "Speaking Out Loud About Bisexuality: Biphobia in the Gay and Lesbian Community". Journal of Bisexuality. 8 (1–2): 82. doi:10.1080/15299710802142259. S2CID 144416441.

- ^ Managing Heterosexism and Biphobia: A Revealing Black Bisexual Male Perspective. 2008-01-01. ISBN 9780549622482.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Michael Musto, April 7, 2009. Ever Meet a Real Bisexual? Archived April 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, The Village Voice

- ^ Yoshino, Kenji (January 2000). "The Epistemic Contract of Bisexual Erasure" (PDF). Stanford Law Review. 52 (2). Stanford Law School: 353–461. doi:10.2307/1229482. JSTOR 1229482.

- ^ a b Dworkin, SH (2001). "Treating the bisexual client". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 57 (5): 671–80. doi:10.1002/jclp.1036. PMID 11304706.

- ^ "Do Bisexual Men Really Exist?". Retrieved 2017-02-12.

- ^ Ka'ahumanu, Lani; Yaeger, Rob. "Biphobia". LGBT Resource Center UC San Diego. UC San Diego. Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- ^ "Situational Homosexuality". American Psychological Association. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ Matsick, Jes L.; Rubin, Jennifer D (June 2018). "Bisexual prejudice among lesbian and gay people: Examining the roles of gender and perceived sexual orientation". Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 5 (2): 143–155. doi:10.1037/sgd0000283.

- ^ Fahs, Breanne (2009-11-13). "Compulsory Bisexuality?: The Challenges of Modern Sexual Fluidity". Journal of Bisexuality. 9 (3–4): 431–449. doi:10.1080/15299710903316661. ISSN 1529-9716.

- ^ Roffee, James A.; Waling, Andrea (2016-10-10). "Rethinking microaggressions and anti-social behaviour against LGBTIQ+ youth". Safer Communities. 15 (4): 190–201. doi:10.1108/SC-02-2016-0004. S2CID 151493252.

- ^ Word Of The Gay: BisexualErasure May 16, 2008 "Queers United"

- ^ The B Word Archived 2021-06-19 at Wikiwix Suresha, Ron. "The B Word," Options (Rhode Island), November 2004

- ^ Hutchins, Loraine (2005). "Sexual Prejudice: The erasure of bisexuals in academia and the media". American Sexuality. Vol. 3, no. 4. National Sexuality Resource Center. Archived from the original on 2007-12-16.

- ^ Hutchins, Loraine. "Sexual Prejudice—The erasure of bisexuals in academia and the media". American Sexuality Magazine. San Francisco, CA: National Sexuality Resource Center, San Francisco State University. Archived from the original on 2007-12-16. Retrieved 2007-07-19.

- ^ Bi Men: Coming Out Every Which Way, Ron Jackson Suresha, Pete Chvany – 2013

- ^ Social Work Practice with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People, Gerald P. Mallon—2017

- ^ Fritz Klein, Karen Yescavage, Jonathan Alexander (2012) "Bisexuality and Transgenderism: InterSEXions of the Others"

- ^ Abbie E. Goldberg (2016) "The SAGE Encyclopedia of LGBTQ Studies"

- ^ a b c d e f g h Eisner, Shiri (2013). Bi: Notes for a Bisexual Revolution (English ed.). Seal Press. p. 345. ISBN 978-1580054751. Archived from the original on April 15, 2023. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ "It's Just A Phase" Is Just A Phrase, The Bisexual Index

- ^ "Bisexuals and the Slut Myth", presented at the 9th International Conference on Bisexuality

- ^ "GLAAD: Cultural Interest Media". Archived from the original on April 19, 2006.

- ^ "Are Bisexuals Really Less Monogamous Than Everyone Else?". Psychology Today. Retrieved 2017-02-12.

- ^ Dodd, S. J. (2021-07-19). The Routledge International Handbook of Social Work and Sexualities. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-40861-4.

- ^ Cipriano, Allison E.; Nguyen, Daniel; Holland, Kathryn J. (2022-10-02). ""Bisexuality Isn't Exclusionary": A Qualitative Examination of Bisexual Definitions and Gender Inclusivity Concerns among Plurisexual Women". Journal of Bisexuality. 22 (4): 557–579. doi:10.1080/15299716.2022.2060892. ISSN 1529-9716.

- ^ Flanders, Corey E. (January–March 2017). "Defining Bisexuality: Young Bisexual and Pansexual People's Voices". Journal of Bisexuality. 17 (1): 39–57. doi:10.1080/15299716.2016.1227016. S2CID 151944900.

- ^ Dodge, Brian; Schnarrs, Phillip W.; Reece, Michael; Martinez, Omar; Goncalves, Gabriel; Malebranche, David; Van Der Pol, Barbara; Nix, Ryan; Fortenberry, J. Dennis (2012-01-01). "Individual and Social Factors Related to Mental Health Concerns among Bisexual Men in the Midwestern United States". Journal of Bisexuality. 12 (2): 223–245. doi:10.1080/15299716.2012.674862. ISSN 1529-9716. PMC 3383005. PMID 22745591.

- ^ Gonzales, V; Washienko, K M; Krone, M R; Chapman, L I; Arredondo, E M; Huckeba, H J; Downer, A (1999). "Sexual and drug-use risk factors for HIV and STDs: a comparison of women with and without bisexual experiences". American Journal of Public Health. 89 (12): 1841–1846. doi:10.2105/ajph.89.12.1841. PMC 1509027. PMID 10589313.

- ^ Makadon MD, Harvey J; Ard MD, MPH, Kevin L (2012-07-09). "Improving the Health Care of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender People: Understanding and Eliminating Health Disparities" (PDF). Fenway Institute. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-08-20. Retrieved 2015-10-09.

- ^ Rehaag, Sean (2009). "Bisexuals need not apply: a comparative appraisal of refugee law and policy in Canada, the United States, and Australia". The International Journal of Human Rights. 13 (2–3): 415–436. doi:10.1080/13642980902758226. hdl:10315/8022. S2CID 55379531.

- ^ Mikel L. Walters, Jieru Chen, and Matthew J. Breiding, "The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Findings on Victimization by Sexual Orientation" (Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 2013).

- ^ Kann, Laura; Olsen, Emily O'Malley; McManus, Tim; Harris, William A.; Shanklin, Shari L.; Flint, Katherine H.; Queen, Barbara; Lowry, Richard; Chyen, David; Whittle, Lisa; Thornton, Jemekia; Lim, Connie; Yamakawa, Yoshimi; Brener, Nancy; Zaza, Stephanie (2016). "Sexual Identity, Sex of Sexual Contacts, and Health-Related Behaviors Among Students in Grades 9–12 — United States and Selected Sites, 2015". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 65 (9): 1–202. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6509a1. PMID 27513843.

- ^ Bostwick, Wendy B.; Boyd, Carol J.; Hughes, Tonda L.; McCabe, Sean Esteban (2010). "Dimensions of Sexual Orientation and the Prevalence of Mood and Anxiety Disorders in the United States". American Journal of Public Health. 100 (3): 468–475. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942. PMC 2820045. PMID 19696380.

- ^ a b c "A Survey of LGBT Americans: The LGBT Population and Its Sub-Groups" (Pew Research Center, June 13, 2013).

- ^ "Bisexuals and Health Risks". National LGBT Cancer Network. 11 July 2018. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022.

- ^ Wilkinson, Sue (1996). "Bisexuality as Backlash". In Harne, Lynne (ed.). All the Rage: Reasserting Radical Lesbian Feminism. Elaine Miller. New York City: Teacher's College Press. pp. 75–89. ISBN 978-0-807-76285-1. OCLC 35202923.

- ^ "Common Lives/Lesbian Lives Records, Iowa Women's Archives, University of Iowa Libraries, Iowa City, Iowa". Archived from the original on August 21, 2015.

- ^ Gerstner, David A. (2006). Routledge International Encyclopedia of Queer Culture. United Kingdom: Routledge. pp. 82–3. ISBN 978-0-415-30651-5. Retrieved October 3, 2012.

- ^ Bindel, Julie (June 12, 2012). "Where's the Politics in Sex?". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ^ Bindel, Julie (November 8, 2008). "It's not me. It's you". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ^ Jeffreys, Sheila (1993). The Lesbian Heresy. Melbourne, Australia: Spinifex Press Pty Ltf. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-875559-17-6. Retrieved October 4, 2012.

- ^ "Donna Haraway – A Cyborg Manifesto". Egs.edu. Archived from the original on 2013-09-22. Retrieved 2015-09-15.

- ^ Bendix, Trish (September 8, 2015). "Why don't lesbians have a pride flag of our own?". AfterEllen. Archived from the original on September 9, 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- ^ Brabaw, Kasandra. "A Complete Guide To All The LGBTQ+ Flags & What They Mean". www.refinery29.com.

- ^ Ess, Mackenzie; Burke, Sara E.; LaFrance, Marianne (2023-07-03). "Gendered Anti-Bisexual Bias: Heterosexual, Bisexual, and Gay/Lesbian People's Willingness to Date Sexual Orientation Ingroup and Outgroup Members". Journal of Homosexuality. 70 (8): 1461–1478. doi:10.1080/00918369.2022.2030618. ISSN 1540-3602. PMID 35112988.

- ^ Garner, Grady L. (2011-09-02). Managing Heterosexism and Biphobia: A Revealing Black Bisexual Male Perspective. ISBN 9781243513434.

Further reading

[edit]- Garber, Marjorie (1995). Bisexuality and the Eroticism of Everyday Life, pp. 20–21, 28, 39.

- Fraser, M., Identity Without Selfhood: Simone de Beauvoir and Bisexuality, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press 1999. p. 124–140.

- Rankin, Sam; Morton, James; Bell, Matthew (May 2015). "Complicated? Bisexual people's experiences of and ideas for improving services" (PDF). Equality Network.

- The fencesitters? Suspicions still haunt the bi/homo divide – article in Xtra, Gay & Lesbian news site, 2006