Seongjeosimni

성저십리 | |

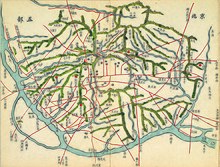

Gyeongjo-obu-do (1861), this map shows Seongjeosimni was included in five administrative divisions of Hanseong, in late period of Joseon dynasty | |

| Alternative name | Seongjeo Shibri |

|---|---|

| Location | Seoul, South Korea |

| Type | Urban periphery |

| Part of | Hanseongbu (Korean: 한성부) |

| History | |

| Founded | 1394[1]: 94–95 |

| Periods | Joseon |

| Seongjeosimni | |

| Hangul | 성저십리 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 城底十里 |

| Revised Romanization | Seongjeosimni |

| McCune–Reischauer | Sŏngjŏshimni |

Seongjeosimni (Korean: 성저십리; Hanja: 城底十里, or sometimes romanized as Seongjeo Shibri[2]) was the peripheral area of Joseon's capital city, Hanseongbu (한성부), literally meaning areas 10 Ri (Korean mile) around the Fortress Wall of Seoul. Though this area was outside of the Fortress Wall, clearly it was an suburb area within city limits of the Hanseongbu. While it was mainly a residential area, some of its components took important role in Joseon's governmental functions, including diplomacy and defense.

History, boundary and function[edit]

Joseon[edit]

Seongjeosimni was part of the Joseon's new capital city Hanseong from the very beginning. While specific demarcations of administrative divisions were changed inside of it, outer boundary of the Seongjeosimni was almost never changed during the entire age of Joseon. Historical records in Joseon, including the Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty, describes boundary of the Seongjeosimni as following; north to the Deoksucheon (덕수천), south to the Noryang (노량), east to the Songyewon (송계원), and west to the Yanghwajin (양화진). These records show that specific area of Seongjeosimni was not exactly 10 Ri from the Fortress Wall, but around 10 Ri, since there was no modernized technology of cartography to measure distance in straight line.[1]: 95–98

In early period of Joseon, one of the Seongjeosimni's main function was tree farm to provide wooden materials for the national government. To achieve this policy, new settlements and deforestation were strictly prohibited in Seongjeosimni. Instead, government-led granaries to store tax payed by grains, diplomatic missions and military post for defense of the capital city filled this sparsely populated area. As there was not a notifiable group of population, national government of Joseon in early period did not have much attention on local governance of the Seongjeosimni. So, although residents in the Seongjeosimni were clearly under jurisdiction of the Hanseong, sometimes, the national government overlooked other authorities governing the adjacent local regions outside of Hanseong city to mobilize the residents in Seongjeosimni.[1]: 100–118

However, as Hanseong city's downtown region inside the Fortress Wall became overly crowded in late 15th century, the national government tried to redevelop the Seongjeosimni as residential area. This new approach was also supported by growth of agriculture and commerce in Joseon's middle period, resulting prosperity of the Seongjeosimni as suburb of the Hanseong city's downtown area in late period of the Joseon dynasty. For example, in the reign of the King Sejong, number of households in Seongjeosimni was 1,779 while households inside the Fortress wall was 17,015. Then in year 1789 when was reign of the King Jeongjo number of former expanded to 21,835 while the latter hit only 22,094. This huge economic and social growth of Seongjeosimni had drawn interest of national government around late 18th century.[3]: 124 So from 1751 to 1788, national government of Joseon realigned administrative divisions of Hanseong, to clarify that local governance of Seongjeosimni belongs strictly to the Hanseong city.[1]: 124–130

Korean Empire and Colonial Korea[edit]

During short reign of the Korean Empire, the national government tried to industrialize itself. Some of these efforts were put into Seongjeosimni area especially around Seodaemun, such as improving roads for logistics.[4]: 306–309 However, when the Japanese Empire took colonial power over Korea, Japanese-led government in Joseon's primary concern was protecting interests of Japanese in Korea. Japanese residents in colonial Joseon were mainly concentrated around southside inside of the Fortress Wall, an area named by Koreans as 'Namchon' (남촌; lit. Southern village), and another area populated by Japanese was Yongsan.[4]: 316–327 Following this geographic status, in 1914, Japanese Government-General changed name of colonial Joseon's capital from 'Hanseong' to 'Keijō', and reduced its city limit to areas a lot close to the Fortress Wall and Yongsan. Yet since this sudden shrink of Keijō(Seoul)'s city limit was unrealistic as the city was growing faster than any before, Government-General had to expand city limit of Keijō. This policy change in 1936 put most of Seongjeosimni's major area back into Keijō's city limit.[5]: 106–108

Heritages and notable places[edit]

History of the Seongjeosimni can still be found in contemporary Seoul, as many of nowaday Seoul's administrative divisions have their etymological origin from that of the Seongjeosimni. This etymologic cases include Yeonhui-dong of Seodaemun District and Yongsan District.

The most prosperous region among the Seongjeosimni in late Joseon period was a place called Seogyo (서교; 西郊), corresponding to contemporary Jongno District's Gyonam-dong, Muak-dong and Seodaemun District's Cheonyeon-dong and Hyeonjeo-dong. It was primarily designed as place for Joseon's international relations, since Seogyo was essential node along the passage connecting capital city of China and Korea. For example, at the heart of this place, a famous building named Mohwagwan (모화관; 慕華館) and its symbolic gate Yeongeunmun existed. It was mainly a state guest house for welcoming the chinese diplomats, but also was an event hall for various important state ceremonies. Another important facility was Gyeonggigamyeong (경기감영), a government agency for local governance of Gyeonggi-do and defense of the capital city, Hanseong. These facilities later encouraged Seogyo region's international and commercial development.[3]: 115–119

See also[edit]

Notes and References[edit]

- ^ a b c d 김, 경록; 유, 승희; 김, 경태; 이, 현진; 정, 은주; 최, 진아; 이, 민우; 진, 윤정 (2019-06-03). 조선시대 다스림으로 본 성저십리 (서울역사중점연구 5) [Seongjeosimni in governance of Joseon (Studies on special topics of Seoul History, Vol. 5.)] (in Korean). Seoul: Seoul Historiography Institute. ISBN 9791160710670.

- ^ Shin, Ye-Kyeong (2013-11-04). "Axes of urban growth: urbanization and railway stations in Seoul, 1900–1945". Planning Perspectives. 28 (4): 628–639. doi:10.1080/02665433.2013.828446.

- ^ a b Lee, Wang-moo (2016). "View from the map of Hansungwonmangdo to description of landscape and change in westside of Seoul in the end of the 19th century". Jangseogak (in Korean). 36: 104–123. doi:10.25024/jsg.2016..36.104. Retrieved 2024-02-20.

- ^ a b 김, 백영; 서, 현주; 정, 태헌; 김, 제정; 김, 종근; 염, 복규; 소, 현숙; 김, 정인 (2015-12-20). 서울2천년사 제26권 경성부 도시행정과 사회 [two thousand years of Seoul's history, Vol. 26., City management and society of Keijō-fu] (in Korean). Seoul: Seoul Historiography Institute. ISBN 9788994033891.

- ^ Jung, Yeo-jin; Han, Dong-soo (May 2021). "The Expansion of Administrative Districts in Gyeongseong and the Perception of the Suburbs - An Analysis of the a featured articles on the suburban areas in the newspaper, 1920~1930s -". Journal of the Korean Institute of Culture Architecture (in Korean). 74: 103–114. Retrieved 2024-02-25.