Opioid use disorder

| Opioid use disorder | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Opioid addiction,[1] problematic opioid use,[1] opioid abuse,[2] opioid dependence[3] |

| |

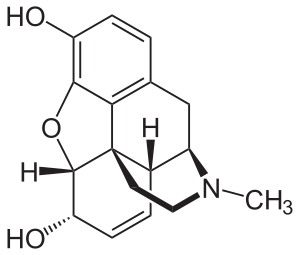

| Molecular structure of morphine | |

| Specialty | Addiction medicine, psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Strong desire to use opioids, increased tolerance to opioids, failure to meet obligations, trouble with reducing use, withdrawal syndrome with discontinuation[4][5] |

| Complications | Opioid overdose, hepatitis C, marriage problems, unemployment, poverty[4][5] |

| Duration | Long term[6] |

| Causes | Opioids[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on criteria in the DSM-5[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Alcoholism |

| Treatment | Opioid replacement therapy, behavioral therapy, twelve-step programs, take home naloxone[7][8][9] |

| Medication | Buprenorphine, methadone, naltrexone[7][10] |

| Frequency | 16 million[11] |

| Deaths | 120,000[11] |

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a substance use disorder characterized by cravings for opioids, continued use despite physical and/or psychological deterioration, increased tolerance with use, and withdrawal symptoms after discontinuing opioids. Opioid withdrawal symptoms include nausea, muscle aches, diarrhea, trouble sleeping, agitation, and a low mood.[12] Addiction and dependence are important components of opioid use disorder.[13]

Risk factors include a history of opioid misuse, current opioid misuse, young age, socioeconomic status, race, untreated psychiatric disorders, and environments that promote misuse (social, family, professional, etc.).[14][15] Complications may include opioid overdose, suicide, HIV/AIDS, hepatitis C, and problems meeting social or professional responsibilities.[16][17] Diagnosis may be based on criteria by the American Psychiatric Association in the DSM-5.[17]

Opioids include substances such as heroin, morphine, fentanyl, codeine, dihydrocodeine, oxycodone, and hydrocodone.[5][6] A useful standard for the relative strength of different opioids is morphine milligram equivalents (MME).[18] It is recommended for clinicians to refer to daily MMEs when prescribing opioids to decrease the risk of misuse and adverse effects.[19] Long-term opioid use occurs in about 4% of people following their use for trauma or surgery-related pain.[20] In the United States, most heroin users begin by using prescription opioids that may also be bought illegally.[21][22]

People with opioid use disorder are often treated with opioid replacement therapy using methadone or buprenorphine.[23] Such treatment reduces the risk of death.[23] Additionally, they may benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy, other forms of support from mental health professionals such as individual or group therapy, twelve-step programs, and other peer support programs.[24] The medication naltrexone may also be useful to prevent relapse.[10][8] Naloxone is useful for treating an opioid overdose and giving those at risk naloxone to take home is beneficial.[25]

This disorder is much more prevalent than first realized.[26] In 2020, the CDC estimated that nearly 3 million people in the U.S. were living with OUD and more than 65,000 people died by opioid overdose, of whom more than 15,000 overdosed on heroin.[27][28] In 2022, the U.S. reported 81,806 deaths caused by opioid-related overdoses. Canada reported 32,632 opioid-related deaths between January 2016 and June 2022.[29][30]

History

[edit]

Historical misuse

[edit]Opiate misuse has been recorded at least since 300 BC. Greek mythology describes Nepenthe ("free from sorrow") and its use by the hero of the Odyssey. Opioids have been used in the Near East for centuries. The purification and isolation of opiates occurred in the early 19th century.[31] In the early 2000s, buprenorphine was one of the first opioid dependence drugs approved in the U.S. to combat opioid abuse, after decades of research led to the development of drugs to fight opioid use disorder.[32]

Historical treatment

[edit]Levacetylmethadol (LAAM) was formerly used to treat opioid dependence. In 2003, its manufacturer discontinued production. There are no available generic versions. LAAM produced long-lasting effects, which allowed the person receiving treatment to visit a clinic only three times per week, as opposed to daily as with methadone.[33] In 2001, LAAM was removed from the European market due to reports of life-threatening ventricular rhythm disorders.[34] In 2003, Roxane Laboratories, Inc. discontinued it in the U.S.[35]

Diagnosis

[edit]The DSM-5 guidelines for the diagnosis of opioid use disorder require that the individual has a significant impairment or distress related to opioid uses.[4] To make the diagnosis two or more of 11 criteria must be present in a given year:[4]

- More opioids are taken than intended

- The individual is unable to decrease the number of opioids used

- Large amounts of time are spent trying to obtain opioids, use opioids, or recover from taking them

- The individual has cravings for opioids

- Difficulty fulfilling professional duties at work or school

- Continued use of opioids leading to social and interpersonal consequences

- Decreased social or recreational activities

- Using opioids despite being in physically dangerous settings

- Continued use despite opioids worsening physical or psychological health (i.e. depression, constipation)

- Tolerance

- Withdrawal

The severity can be classified as mild, moderate, or severe based on the number of criteria present.[6] The tolerance and withdrawal criteria are not considered to be met for individuals taking opioids solely under appropriate medical supervision.[4] Addiction and dependence are components of a substance use disorder; addiction is the more severe form.[36]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Opioid intoxication

[edit]Signs and symptoms of opioid intoxication include:[5][37]

- Decreased perception of pain

- Euphoria

- Confusion

- Desire to sleep

- Nausea

- Constipation

- Miosis (pupil constriction)

- Bradycardia (slow heart rate)

- Hypotension (low blood pressure)

- Hypokinesis (slowed movement)

- Head nodding

- Slurred speech

- Hypothermia (low body temperature)

Opioid overdose

[edit]

Signs and symptoms of opioid overdose include, but are not limited to:[39]

- Pin-point pupils may occur. Patient presenting with dilated pupils may still be experiencing an opioid overdose.

- Decreased heart rate

- Decreased body temperature

- Decreased breathing

- Altered level of consciousness. People may be unresponsive or unconscious.

- Pulmonary edema (fluid accumulation in the lungs)

- Shock

- Death

Withdrawal

[edit]Opioid withdrawal can occur with a sudden decrease in, or cessation of, opioids after prolonged use.[40][41][42] Onset of withdrawal depends on the half-life of the opioid that was used last.[43] With heroin this typically occurs five hours after use; with methadone, it may take two days.[43] The length of time that major symptoms occur also depends on the opioid used.[43] For heroin withdrawal, symptoms are typically greatest at two to four days and can last up to two weeks.[44][43] Less significant symptoms may remain for an even longer period, in which case the withdrawal is known as post-acute-withdrawal syndrome.[43]

- Agitation[4]

- Anxiety[4]

- Muscle pains[4]

- Increased tearing[4]

- Trouble sleeping[4]

- Runny nose[4]

- Sweating[4]

- Yawning[4]

- Goose bumps[4]

- Dilated pupils[4]

- Diarrhea[4]

- Fast heart rate[43]

- High blood pressure[43]

- Abdominal cramps[43]

- Shakiness[43]

- Cravings[43]

- Sneezing[43]

- Bone pain

- Increased body temperature

- Hyperalgesia

- Ptosis (drooping eyelids)

- Teeth chattering

- Emotional pain

- Stress

- Weakness

- Malaise

- Alexithymia

- Dysphoria

Treatment of withdrawal may include methadone and buprenorphine. Medications for nausea or diarrhea may also be used.[41]

Cause

[edit]Opioid use disorder can develop as a result of self-medication.[45] Scoring systems have been derived to assess the likelihood of opiate addiction in chronic pain patients.[46] Healthcare practitioners have long been aware that despite the effective use of opioids for managing pain, empirical evidence supporting long-term opioid use is minimal.[47][48][49][50][51] Many studies of patients with chronic pain have failed to show any sustained improvement in their pain or ability to function with long-term opioid use.[48][52][53][54][51]

A 2024 literature review suggests that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are significantly associated with opioid use disorder later in life. ACEs include witnessing violence, experiencing abuse and neglect, and growing up with a family member with a mental health or substance abuse problem.[55]

Mechanism

[edit]Addiction

[edit]Addiction is a brain disorder characterized by compulsive drug use despite adverse consequences.[36][56][57][58] Addiction involves the overstimulation of the brain's mesocorticolimbic reward circuit (reward system), essential for motivating behaviors linked to survival and reproductive fitness, like seeking food and sex.[59] This reward system encourages associative learning and goal-directed behavior. In addiction, substances overactivate this circuit, causing compulsive behavior due to changes in brain synapses.[60]

In the brain's mesolimbic region, Nucleus Accumbens (NAc) accepts releases of dopamine triggered by the neurotransmitters. The brain reward circuitry is rooted in these networks, interacting between the mesolimbic and prefrontal cortex; these systems link motivation, anti-stress, incentive salience, and wellbeing.[61]

The incentive-sensitization theory differentiates between "wanting" (driven by dopamine in the reward circuit) and "liking" (related to brain pleasure centers).[62] This explains the addictive potential of non-pleasurable substances and the persistence of opioid addiction despite tolerance to their euphoric effects. Addiction surpasses mere avoidance of withdrawal, involving cues and stress that reactivate reward-driven behaviors.[59] This is thought to be an important reason detoxification alone is unsuccessful 90% of the time.[63][64][65]

Overexpression of the gene transcription factor ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens plays a crucial role in the development of an addiction to opioids and other addictive drugs by sensitizing drug reward and amplifying compulsive drug-seeking behavior.[56][66][67][68] Like other addictive drugs, overuse of opioids leads to increased ΔFosB expression in the nucleus accumbens.[66][67][68][69] Opioids affect dopamine neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens via the disinhibition of dopaminergic pathways as a result of inhibiting the GABA-based projections to the ventral tegmental area (VTA) from the rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg), which negatively modulate dopamine neurotransmission.[70][71] In other words, opioids inhibit the projections from the RMTg to the VTA, which in turn disinhibits the dopaminergic pathways that project from the VTA to the nucleus accumbens and elsewhere in the brain.[70][71]

The differences in the genetic regions encoding the dopamine receptors for each individual may help to elucidate part of the risk for opioid addiction and general substance abuse.[10] Studies of the D2 Dopamine Receptor, in particular, have shown some promising results. One specific SNP is at the TaqI RFLP (rs1800497). In a study of 530 Han Chinese heroin-addicted individuals from a Methadone Maintenance Treatment Program, those with the specific genetic variation showed higher mean heroin consumption by around double those without the SNP.[72] This study helps to show the contribution of dopamine receptors to substance addiction and more specifically to opioid abuse.[72]

Neuroimaging has shown functional and structural alterations in the brain.[73] Chronic intake of opioids such as heroin may cause long-term effects in the orbitofrontal area (OFC), which is essential for regulating reward-related behaviors, emotional responses, and anxiety.[74] Moreover, neuroimaging and neuropsychological studies demonstrate dysregulation of circuits associated with emotion, stress and high impulsivity.[75]

Dependence

[edit]Opioid dependence can occur as physical dependence, psychological dependence, or both.[76] Drug dependence is an adaptive state associated with a withdrawal syndrome upon cessation of repeated exposure to a stimulus (e.g., drug intake).[56][57][58] Dependence is a component of a substance use disorder.[36][77] Opioid dependence can manifest as physical dependence, psychological dependence, or both.[76][57][77]

Increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) signaling in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) has been shown to mediate opioid-induced withdrawal symptoms via downregulation of insulin receptor substrate 2 (IRS2), protein kinase B (AKT), and mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2).[56][78] As a result of downregulated signaling through these proteins, opiates cause VTA neuronal hyperexcitability and shrinkage (specifically, the size of the neuronal soma is reduced).[56] It has been shown that when an opiate-naive person begins using opiates in concentrations that induce euphoria, BDNF signaling increases in the VTA.[79]

Upregulation of the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) signal transduction pathway by cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), a gene transcription factor, in the nucleus accumbens is a common mechanism of psychological dependence among several classes of drugs of abuse.[76][56] Upregulation of the same pathway in the locus coeruleus is also a mechanism responsible for certain aspects of opioid-induced physical dependence.[76][56]

A scale was developed to compare the harm and dependence liability of 20 drugs.[80] The scale uses a rating of zero to three to rate physical dependence, psychological dependence, and pleasure to create a mean score for dependence.[80] Selected results can be seen in the chart below. Heroin and morphine both scored highest, at 3.0.[80]

| Drug | Mean | Pleasure | Psychological dependence | Physical dependence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heroin/Morphine | 3.00 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Cocaine | 2.39 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 1.3 |

| Alcohol | 1.93 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.6 |

| Benzodiazepines | 1.83 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.8 |

| Tobacco | 2.21 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 1.8 |

Opioid receptors

[edit]A genetic basis for the efficacy of opioids in the treatment of pain has been demonstrated for several specific variations, but the evidence for clinical differences in opioid effects is not clear.[11] There is an estimated 50% genetic contribution to opioid use disorder.[11][81] The pharmacogenomics of the opioid receptors and their endogenous ligands have been the subject of intensive activity in association studies. These studies test broadly for a number of phenotypes, including opioid dependence, cocaine dependence, alcohol dependence, methamphetamine dependence/psychosis, response to naltrexone treatment, personality traits, and others. Major and minor variants have been reported for every receptor and ligand coding gene in both coding sequences, as well as regulatory regions.[81] Research on endogenous opioid receptors has focused around OPRM1 gene, which encodes the μ-opioid receptor, and the OPRK1 and OPRD1 genes, which encode the κ and δ receptors, respectively.[81] Newer approaches shift away from analysis of specific genes and regions, and are based on an unbiased screen of genes across the entire genome, which have no apparent relationship to the phenotype in question. These GWAS studies yield a number of implicated genes, although many of them code for seemingly unrelated proteins in processes such as cell adhesion, transcriptional regulation, cell structure determination, and RNA, DNA, and protein handling/modifying.[82]

118A>G variant

[edit]While over 100 variants have been identified for the opioid mu-receptor, the most studied mu-receptor variant is the non-synonymous 118A>G variant, which results in functional changes to the receptor, including lower binding site availability, reduced mRNA levels, altered signal transduction, and increased affinity for beta-endorphin. In theory, all these functional changes would reduce the impact of exogenous opioids, requiring a higher dose to achieve the same therapeutic effect. This points to a potential for greater addictive capacity in individuals who require higher dosages to achieve pain control. But evidence linking the 118A>G variant to opioid dependence is mixed, with associations shown in a number of study groups, but negative results in other groups.[83] One explanation for the mixed results is the possibility of other variants that are in linkage disequilibrium with the 118A>G variant and thus contribute to different haplotype patterns more specifically associated with opioid dependence.[83]

Non-opioid receptor genes

[edit]While opioid receptors have been the most widely studied, a number of other genes have been implicated in OUD. Higher numbers of (CA) repeats flanking the preproenkephalin gene, PENK, have been associated with opiate dependence.[84] There have been mixed results for the MCR2 gene, encoding melanocortin receptor type 2, implicating both protection and risk to heroin addiction.[84] A number of enzymes in the cytochrome P450 family may also play a role in dependence and overdose due to variance in breakdown of opioids and their receptors. There are also multiple potential complications with combining opioids with antidepressants and antiepileptic drugs (both common drugs for chronic pain patients) because of their effects on inducing CYP enzymes.[85] Genotyping of CYP2D6 in particular may play a role in helping patients with individualized treatment for OUD and other drug addictions.[85]

Prevention

[edit]The CDC gives prescribers specific recommendations for starting opioids, clinically appropriate use, and assessing risks associated with opioid therapy.[86] Improving opioid prescribing guidelines and practices can help reduce unnecessary exposure to opioids, which in turn lowers the risk of developing OUD (opioid use disorder). Healthcare providers should strictly follow evidence-based guidelines, such as the CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain, to ensure safe and appropriate use.[87] Another way to prevent OUD is educating the public about the risks of prescription opioids and illegal substances like fentanyl. Awareness campaigns, community outreach programs, and school-based education initiatives can help people make informed decisions about opioid use and recognize the signs of addiction early on.[88]

Large U.S. retail pharmacy chains are implementing protocols, guidelines, and initiatives to take back unused opioids, providing naloxone kits, and being vigilant about suspicious prescriptions.[89][90][91] Insurance programs can help limit opioid use by setting quantity limits on prescriptions or requiring prior authorizations for certain medications.[92] Many U.S. officials and government leaders have become involved in implementing preventative measures to decrease opioid usage in the United States.[93] Targeted education of medical providers and government officials can lead to provisions affecting opioid distribution by healthcare providers.[10]

A 2024 literature review found a strong association between ACEs and opioid abuse later in life, suggesting that a high ACE score should be considered a risk factor for opioid abuse. Screening ACEs before prescribing or implementing interventions involving opioids can mitigate the potential for misuse.[55]

Opioid overdose

[edit]Naloxone is used for the emergency treatment of an overdose.[94] It can be given by many routes (e.g., intramuscular (IM), intravenous (IV), subcutaneous, intranasal, and inhalation) and acts quickly by displacing opioids from opioid receptors and preventing the activation of these receptors.[91] Naloxone kits are recommended for laypersons who may witness an opioid overdose, for people with large prescriptions for opioids, those in substance use treatment programs, and those recently released from incarceration.[95] Since this is a life-saving medication, many areas of the U.S. have implemented standing orders for law enforcement to carry and give naloxone as needed.[96][97] In addition, naloxone can be used to challenge a person's opioid abstinence status before starting a medication such as naltrexone, which is used in the management of opioid addiction.[98]

Good Samaritan laws typically protect bystanders who administer naloxone. In the U.S., at least 40 states have Good Samaritan laws to encourage bystanders to take action without fear of prosecution.[99] As of 2019, 48 states give pharmacists the authority to distribute naloxone without an individual prescription.[100]

Homicide, suicide, accidents and liver disease are also opioid-related causes of death for those with OUD.[101][102] Many of these causes of death are unnoticed due to the often limited information on death certificates.[101][103]

Mitigation

[edit]The "CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain-United States, 2022" provides recommendations related to opioid misuse, OUD, and opioid overdoses.[18] It reports a lack of clinical evidence that "abuse-deterrent" opioids (e.g., OxyContin), as labeled by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, are effective for OUD risk mitigation.[18][104] CDC guidance suggests the prescription of immediate-release opioids instead of opioids that have a long duration (long-acting) or opioids that are released over time (extended release).[18] Other recommendations include prescribing the lowest opioid dose that successfully addresses the pain in opioid-naïve patients and collaborating with patients who already take opioid therapy to maximize the effect of non-opioid analgesics.[18]

While receiving opioid therapy, patients should be periodically evaluated for opioid-related complications and clinicians should review state prescription drug monitoring program systems.[18] The latter should be assessed to reduce the risk of overdoses in patients due to their opioid dose or medication combinations.[18] For patients receiving opioid therapy in whom the risks outweigh the benefits, clinicians and patients should develop a treatment plan to decrease their opioid dose incrementally.[18]

Compartmental models are mathematical frameworks used to assess and describe complex topics such as the opioid crisis. Applied compartmental models are used in public health to assess the effectiveness of interventions in opioid use disorder. Most overdoses in 2020 were due to synthetic opioids, highlighting a need to incorporate synthetic opioid data in the models.[105]

For more specific mitigation strategies regarding opioid overdoses, see opioid overdose § Prevention.

Management

[edit]Opioid use disorders typically require long-term treatment and care with the goal of reducing the person's risks and improving their long-term physical and psychological condition.[106]

First-line management involves the use of opioid replacement therapies, particularly methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone. Withdrawal management alone is strongly discouraged, because of its association with elevated risks of HIV and hepatitis C transmission, high rates of overdose deaths, and nearly universal relapse.[107][108] This approach is seen as ineffective without plans for transition to long-term evidence-based addiction treatment, such as opioid agonist treatment.[63] Though treatment reduces mortality rates, the first four weeks after treatment begins and the four weeks after treatment ceases are the riskiest times for drug-related deaths.[7] These periods of increased vulnerability are significant because many of those in treatment leave programs during these periods.[7] There is evidence that people with opioid use disorder who are dependent on pharmaceutical opioids may require a different management approach from those who take heroin.[109]

Medication

[edit]Opioid replacement therapy (ORT), also known as opioid substitution therapy (OST) or Medications for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD), involves replacing an opioid, such as heroin.[110][111] Commonly used drugs for ORT are methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone (Suboxone), which are taken under medical supervision.[111] Buprenorphine/naloxone is usually preferred over methadone because of its safety profile, which is considered significantly better, primarily with regard to its risk of overdose[112] and effects on the heart (QTc prolongation).[113][114]

Buprenorphine/naloxone, methadone, and naltrexone are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for medication-assisted treatment (MAT).[115] In the U.S., the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) certifies opioid treatment programs (OTPs), where methadone can be dispensed at methadone clinics.[116] As of 2023, the Waiver Elimination (MAT Act), also known as the "Omnibus Bill", removed the federal requirement for medical providers to obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine, in an attempt to increase access to OUD treatment.[117]

The driving principle behind ORT is the patient's reclamation of a self-directed life.[118] ORT facilitates this process by reducing symptoms of drug withdrawal and drug cravings.[111][118] In some countries (not the U.S. or Australia),[111] regulations enforce a limited time for people on ORT programs that conclude when a stable economic and psychosocial situation is achieved. (People with HIV/AIDS or hepatitis C are usually excluded from this requirement.) In practice, 40–65% of patients maintain abstinence from additional opioids while receiving opioid replacement therapy and 70–95% can reduce their use significantly.[111] Medical (improper diluents, non-sterile injecting equipment), psychosocial (mental health, relationships), and legal (arrest and imprisonment) issues that can arise from the use of illegal opioids are concurrently eliminated or reduced.[111] Clonidine or lofexidine can help treat the symptoms of withdrawal.[119]

The period when initiating methadone and the time immediately after discontinuing treatment with both drugs are periods of particularly increased mortality risk, which should be dealt with by both public health and clinical strategies.[7] ORT has proved to be the most effective treatment for improving the health and living condition of people experiencing illegal opiate use or dependence, including mortality reduction[111][120][7] and overall societal costs, such as the economic loss from drug-related crime and healthcare expenditure.[111] A review of UK hospital policies found that local guidelines delayed access to substitute opioids, for instance by requiring lab tests to demonstrate recent use or input from specialist drug teams before prescribing. Delays to access can increase people's risk of discharging themselves early against medical advice.[121][122] ORT is endorsed by the World Health Organization, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and UNAIDS as effective at reducing injection, lowering risk for HIV/AIDS, and promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy.[7]

Buprenorphine and methadone work by reducing opioid cravings, easing withdrawal symptoms, and blocking the euphoric effects of opioids via cross-tolerance,[123] and in the case of buprenorphine, a high-affinity partial opioid agonist, also due to opioid receptor saturation.[124]

Buprenorphine and buprenorphine/naloxone

[edit]Buprenorphine can be administered either as a standalone product or in combination with the opioid antagonist naloxone. This inclusion is strategic: it deters misuse by preventing the crushing and injecting of the medication, encouraging instead the prescribed sublingual (under the tongue) route.[111] Buprenorphine/naloxone formulations are available as tablets and films;[125] these formulations operate efficiently when taken sublingually. In this form, buprenorphine's bioavailability remains robust (35–55%), while naloxone's is significantly reduced (~10%).[126]

Buprenorphine's role as a partial opioid receptor agonist sets it apart from full agonists like methadone. Its unique pharmacological profile makes it less likely to cause respiratory depression, thanks to its "ceiling effect".[127][128] While the risk of misuse or overdose is higher with buprenorphine alone compared to the buprenorphine/naloxone combination or methadone, its usage is linked to a decrease in mortality.[129][7] Approved in the U.S. for opioid dependence treatment in 2002,[130] buprenorphine has since expanded in form, with the FDA approving a month-long injectable version in 2017.[131]

When initiating buprenorphine/naloxone therapy, several critical factors must be considered. These include the severity of withdrawal symptoms, the time elapsed since the last opioid use, and the type of opioid involved (long-acting vs. short-acting).[132] A standard induction method involves waiting until the patient exhibits moderate withdrawal symptoms, as measured by a Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale, achieving a score of around 12. Alternatively, "microdosing" commences with a small dose immediately, regardless of withdrawal symptoms, offering a more flexible approach to treatment initiation.[133] "Macrodosing" starts with a larger dose of Suboxone, a different induction strategy with its own set of considerations.[134]

Methadone

[edit]Methadone is a commonly used full-opioid agonist in the treatment of opioid use disorder. It is effective in relieving withdrawal symptoms and cravings in people with opioid addiction, and can also be used in pain control in certain situations.[129] While methadone is a widely prescribed form of OAT, it often requires more frequent clinical visits compared to buprenorphine/naloxone, which also has a better safety profile and lower risk of respiratory depression and overdose.[135]

Important considerations when initiating methadone include the patient's opioid tolerance, the time since last opioid use, the type of opioid used (long-acting vs. short-acting), and the risk of methadone toxicity.[136] Methadone comes in different forms: tablet, oral solution, or an injection.[129]

One of methadone's benefits is that it can last up to 56 hours in the body, so if a patient misses a daily dose, they will not typically struggle with withdrawal symptoms.[129] Other advantages of methadone include reduction in infectious disease related to injection drug use, and reduced mortality. Methadone has a number of potential side effects, including slowed breathing, nausea, vomiting, restlessness, and headache.[137]

Naltrexone

[edit]Naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist used for the treatment of opioid addiction.[138][139] It is not as widely used as buprenorphine or methadone for OUD due to low rates of patient acceptance, non-adherence due to daily dosing, and difficulty achieving abstinence from opioids before beginning treatment. Additionally, dosing naltrexone after recent opioid use can lead to precipitated withdrawal. Conversely, naltrexone antagonism at the opioid receptor can be overcome with higher doses of opioids.[140] Naltrexone monthly IM injections received FDA approval in 2010 for the treatment of opioid dependence in abstinent opioid users.[138][141]

Other opioids

[edit]Evidence of effects of heroin maintenance compared to methadone are unclear as of 2010.[142] A Cochrane review found some evidence in opioid users who had not improved with other treatments.[143] In Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, long-term injecting drug users who do not benefit from methadone and other medication options may be treated with injectable heroin that is administered under the supervision of medical staff.[144] Other countries where it is available include Spain, Denmark, Belgium, Canada, and Luxembourg.[145] Dihydrocodeine in both extended-release and immediate-release form is also sometimes used for maintenance treatment as an alternative to methadone or buprenorphine in some European countries.[146] Dihydrocodeine is an opioid agonist.[147] It may be used as a second-line treatment.[148] A 2020 systematic review found low-quality evidence that dihydrocodeine may be no more effective than other routinely used medication interventions in reducing illicit opiate use.[149]An extended-release morphine confers a possible reduction of opioid use and with fewer depressive symptoms but overall more adverse effects compared to other forms of long-acting opioids. Retention in treatment was not found to be significantly different.[150] It is used in Switzerland and more recently in Canada.[151]

In pregnancy

[edit]Pregnant women with opioid use disorder can also receive treatment with methadone, naltrexone, or buprenorphine.[152] Buprenorphine appears to be associated with more favorable outcomes compared to methadone for treating opioid use disorder (OUD) in pregnancy. Studies show that buprenorphine is linked to lower risks of preterm birth, greater birth weight, and larger head circumference without increased harm.[153] Compared to methadone, it consistently results in improved birth weight and gestational age, though these findings should be interpreted with caution due to potential biases.[154] Buprenorphine use also correlates with a lower risk of adverse neonatal outcomes, with similar risks of adverse maternal outcomes as methadone.[155] Infants born to buprenorphine-treated mothers generally have higher birth weights, fewer withdrawal symptoms, and a lower likelihood of premature birth.[155] Additionally, these infants often require less treatment for neonatal abstinence syndrome and have mothers who are more likely to start treatment earlier in pregnancy, leading to longer gestations and larger infants.[156]

Behavioral therapy

[edit]Paralleling the variety of medical treatments, there are many forms of psychotherapy and community support for treating OUD. The primary evidence-based psychotherapies include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy (MET), contingency management (CM), and twelve-step programs. Community-based support such as support groups (e.g., Narcotics Anonymous) and therapeutic housing for those with OUD is also an important aspect of healing.[157][158]

Cognitive behavioral therapy

[edit]Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a form of psychosocial intervention that systematically evaluates thoughts, feelings, and behaviors about a problem and works to develop coping strategies to work through those problems.[159] This intervention has demonstrated success in many psychiatric conditions (e.g., depression) and substance use disorders (e.g., tobacco).[160] But the use of CBT alone for OUD has declined due to lack of efficacy, and many rely on medication therapy or medication therapy with CBT, since both were found to be more efficacious than CBT alone.[98] CBT has been shown to be more successful in relapse prevention than treatment of ongoing drug use.[157] It is particularly known for its durability.[161]

Motivational Enhancement Therapy

[edit]Motivational enhancement therapy (MET) is the manualized form of motivational interviewing (MI). MI leverages one's intrinsic motivation to recover through education, formulation of relapse prevention strategies, reward for adherence to treatment guidelines, and positive thinking to keep motivation high—which are based on a person's socioeconomic status, gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and readiness to recover.[98][162][163] Like CBT, MET alone has not shown convincing efficacy for OUD. There is stronger support for combining it with other therapies.[161]

Contingency Management Therapy

[edit]Contingency Management Therapy (CMT) employs similar principles as operant behavioral conditioning, such as using incentives to reach certain goals (e.g., verified abstinence, usually in the form of urine drug testing).[157] This form of psychotherapy has the strongest, most robust empirical support for treating drug addiction.[157][161][164] Outpatient clients are shown to have improved medication compliance, retention, and abstinence when using voucher-based incentives.[157][161] One way this is implemented is to offer take-home privileges for methadone programs. Despite its effectiveness during treatment, effects tend to wane once terminated. Additionally, the cost barrier limits its application in the clinical community.[157]

Twelve-step programs

[edit]While medical treatment may help with the initial symptoms of opioid withdrawal, once the first stages of withdrawal are through, a method for long-term preventative care is attendance at 12-step groups such as Narcotics Anonymous (NA).[165] NA's 12-step process is based on the 12-step facilitation of Alcoholic Anonymous (AA) and centers on peer support, self-help, and spiritual connectedness. Some evidence also supports the use of these programs for adolescents.[166] Multiple studies have shown increased abstinence for those in NA compared to those who are not.[11][167][168][169] Members report a median abstinence length of 5 years.[169]

Novel experimental treatments

[edit]Though medications and behavioral treatments are effective forms for treating OUD, relapse remains a common problem. The medical community has looked to novel technologies and traditional alternative medicines for new ways to approach the issues of continued cravings and impaired executive functioning. While consensus on their efficacy has not been reached, a number of reviews have shown promising results for the use of non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) for reducing cravings in OUD.[170][171] These results are consistent with the use of NIBS for reducing cravings of other substances. Additionally, investigations into the anecdotal evidence of psychedelics like ibogaine have also shown the possibility of decreased cravings and withdrawal symptoms.[172] Ibogaine is illegal in the U.S. but is unregulated in Mexico, Costa Rica, and New Zealand, where many clinics use it for addiction treatment.[173] Research has shown a minor mortality risk due to its cardiotoxic and neurotoxic effects.[172]

In 2024 the FDA approved the NET (NeuroElectric Therapy) device, which reduces withdrawal symptoms by neurostimulation. Used for three to five days of continuous treatment, NET delivers alternating current via surface electrodes placed trans-cranially at the base of the skull on each side of the head.[174][175]

Treatment challenges

[edit]The stigma surrounding addiction can heavily influence opioid addicts not to seek help. Many people view addiction as a moral failing rather than a medical condition, which can lead to feelings of shame and isolation. This stigma can also affect family members, making it difficult for them to support their loved ones effectively.[176]

According to position papers on the treatment of opioid dependence published by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the World Health Organization, care providers should not treat opioid use disorder as the result of a weak moral character or will but as a medical condition.[177][178][179] Some evidence suggests the possibility that opioid use disorders occur due to genetic or other chemical mechanisms that may be difficult to identify or change, such as dysregulation of brain circuitry involving reward and volition. But the exact mechanisms involved are unclear, leading to debate over the influence of biology and free will.[180][181]

Accessing appropriate treatment is often a significant barrier. Factors include:[182]

- Availability of services: In many areas, especially rural regions, there is a lack of treatment facilities or qualified healthcare providers who specialize in opioid use disorder.

- Insurance coverage: People without insurance or those whose plans do not cover substance use disorder treatment may struggle to find affordable care.

- Transportation: For many, getting to treatment facilities can be challenging due to a lack of transportation options.

- Public stigma: Many communities may advocate against establishing treatment programs in their area due to stigma and perceptions of individuals with substance use disorders.

The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA) passed in 2016, with the aim to remove treatment barriers by allocating federal funds to increase accessibility to Medication Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) treatment in rural areas. Telehealth could be a beneficial treatment alternative, especially to people in rural areas with limited access to MOUD treatment.[183]

The variety of treatment modalities available for OUD—such as medication-assisted treatment (MAT), counseling, and residential programs—can be overwhelming. Patients may have difficulty understanding which option best suits them, leading to confusion and potential disengagement from the treatment process. Withdrawal symptoms can be severe and uncomfortable, leading many people to relapse before they complete detoxification or engage fully in recovery programs. The fear of withdrawal often prevents people from seeking help altogether.[184]

Epidemiology

[edit]

Globally, the number of people with opioid dependence increased from 10.4 million in 1990 to 15.5 million in 2010.[7] In 2016, the numbers rose to 27 million people who experienced this disorder.[186] Opioid use disorders resulted in 122,000 deaths worldwide in 2015,[187] up from 18,000 deaths in 1990.[188] Deaths from all causes rose from 47.5 million in 1990 to 55.8 million in 2013.[188][187]

United States

[edit]

The current epidemic of opioid abuse is the most lethal drug epidemic in American history.[22] The crisis can be distinguished by waves of opioid overdose deaths as described by the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention.[189] The first wave began in the 1990s, related to the rise in prescriptions of natural opioids (such as codeine and morphine), semisynthetic opioids (oxycodone, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, and oxymorphone), and synthetic opioids like methadone.[190][189] In the U.S., "the age-adjusted drug poisoning death rate involving opioid analgesics increased from 1.4 to 5.4 deaths per 100,000 population between 1999 and 2010.[191] The second wave dates to around 2010 with the rapid increase in opioid overdoses due to heroin.[190] By this time, there were already four times as many deaths by overdose than in 1999.[191] The age-adjusted drug poisoning death rate involving heroin doubled from 0.7 to 1.4 deaths per 100,000 people between 1999 and 2011 and then continued to increase to 4.1 in 2015.[192] The third wave of overdose deaths began in 2013, related to synthetic opioids, particularly illicitly produced fentanyl.[190] While the illicit fentanyl market has continuously changed, the drug is generally sold as an adulterant in heroin. Research suggests that the rapid increase of fentanyl into the illicit opioid market has been largely supply-side-driven and dates to 2006. Decreasing heroin purity, competition from increased access to prescription medications, and dissemination of "The Siegfried Method" (a relatively simple and cost-effective method of fentanyl production) were major factors in street suppliers' inclusion of fentanyl in their products.[193][194] The current, fourth wave, which began in 2016, has been characterized by polysubstance overdose due to synthetic opioids like fentanyl mixed with stimulants such as methamphetamine or cocaine.[195][196] In 2010, around 0.5% of opioid-related deaths were attributed to mixture with stimulants. This figure increased more than 50-fold by 2021, when about a third of opioid-related deaths, or 34,000, involved stimulant use.[196]

In 2017, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced a public health emergency due to an increase in the misuse of opioids.[197] The administration introduced a strategic framework called the Five-Point Opioid Strategy, which includes providing access recovery services, increasing the availability of reversing agents for overdose, funding opioid misuse and pain research, changing treatments of people managing pain, and updating public health reports related to combating opioid drug misuse.[197][198]

Studies done in the U.S. from 2010 to 2019 revealed that about 86.6% of people in the U.S. who could have benefited from opioid use disorder treatment were not receiving it. Over the past decade, the uptake of medications for opioid use disorder has increased, but there are still many regions with a prevalence of opioid use disorder and lack of medical support.[199]

The U.S. epidemic in the 2000s is related to a number of factors.[200] Rates of opioid use and dependency vary by age, sex, race, and socioeconomic status.[200] With respect to race, the discrepancy in deaths is thought to be due to an interplay between physician prescribing and lack of access to healthcare and certain prescription drugs.[200] Men are at higher risk for opioid use and dependency than women,[201][202] and men also account for more opioid overdoses than women, although this gap is closing.[201] Women are more likely to be prescribed pain relievers, be given higher doses, use them for longer durations, and become dependent upon them faster.[203]

Deaths due to opioid use also tend to skew at older ages than deaths from use of other illicit drugs.[202][204][205] This does not reflect opioid use as a whole, which includes younger people. Overdoses from opioids are highest among people between the ages of 40 and 50,[205] in contrast to heroin overdoses, which are highest among people between the ages of 20 and 30.[204] 21- to 35-year-olds represent 77% of people who enter treatment for opioid use disorder,[206] but the average age of first-time use of prescription painkillers was 21.2 years in 2013.[207] Among the middle class, means of acquiring funds include elder financial abuse and international dealers noticing a lack of enforcement in their transaction scams throughout the Caribbean.[208]

Since 2018, with the federal government's passing of the SUPPORT (Substance Use-Disorder Prevention That Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act) Act, federal restrictions on methadone use for patients receiving Medicare have been lifted.[209] Since March 2020, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, buprenorphine may be dispensed via telemedicine in the U.S.[210][211]

In October 2021, New York Governor Kathy Hochul signed legislation to combat the opioid crisis. This included establishing a program for the use of medication-assisted substance use disorder treatment for incarcerated individuals in state and local correctional facilities, decriminalizing the possession and sale of hypodermic needles and syringes, establishing an online directory for distributors of opioid antagonists, and expanding the number of eligible crimes committed by individuals with a substance use disorder that may be considered for diversion to a substance use treatment program.[212] Until these laws were signed, incarcerated New Yorkers did not reliably have access to medication-assisted treatment and syringe possession was still a class A misdemeanor despite New York authorizing and funding syringe exchange and access programs.[213] This legislation acknowledges the ways New York State laws have contributed to opioid deaths: in 2020 more than 5112 people died from overdoses in New York State, with 2192 deaths in New York City.[214]

As of 2023, the Waiver Elimination (MAT Act), as part of Section 1262 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 (or "Omnibus Bill"), removed the federal requirement for medical providers to obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine, in an attempt to increase access to OUD treatment.[117] Before this bill, practitioners were required to receive a Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA) waiver, also known as "x-waiver", before prescribing buprenorphine. There is also now no longer any limit to the number of patients to whom a provider may prescribe buprenorphine for OUD.[117]

- Charts of deaths involving specific opioids and classes of opioids - US National Institute on Drug Abuse

-

U.S. yearly deaths from all opioid drugs. Included in this number are opioid analgesics, along with heroin and illicit synthetic opioids.[215]

-

U.S. yearly deaths by drug category[215]

-

U.S. yearly opioid overdose deaths involving prescription opioids. Non-methadone synthetics is a category dominated by illegally acquired fentanyl, and has been excluded.[216]

-

U.S. yearly opioid overdose deaths involving heroin[216]

-

U.S. yearly opioid overdose deaths involving psychostimulants (primarily methamphetamine)[216]

Canada

[edit]Canada recorded 32,632 opioid-related deaths between January 2016 and June 2022. The marked increase in opioid toxicity deaths is largely attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic.[217]

Effects of COVID-19 on opioid overdose and telehealth treatment

[edit]Epidemiological research has shown that the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the opioid crisis.[194][218][219] The overarching trend of opioid overdose data has shown a plateau in deaths around 2017–18, with a sudden and acute rise in 2019 primarily attributed to synthetic opioids like fentanyl.[216] In 2020, there were 93,400 drug overdoses in the U.S. with >73% (approximately 69,000) due to opioid overdose.[220] One JAMA review by Gomes et al. showed that estimated years of life loss (YLL) due to opioid toxicity in the U.S. increased by 276%. This increase was particularly felt by those ages 15 to 19, whose YLL increased nearly threefold. Younger male adults had the largest effect size.[219] Other reviews of U.S. and Canadian opioid data coinciding with the onset of COVID-19 suggested significant increases in opioid-related emergency medicine utilization, increased positivity for opioids, and surprisingly no to decreased change in naloxone dispensation.[221]

Telehealth played a large role in OUD treatment access, and legislation on telehealth continues to evolve. A study of Medicare beneficiaries with new-onset OUD showed that those who received telehealth services had a 33% lower risk of death by overdose.[222] Minority groups such as Black and Hispanic Americans have also been shown to benefit from the increased access due to telehealth programs introduced during the pandemic, despite increasing disparity gaps in other OUD-related outcomes.[223] The DEA and HHS have extended telemedicine flexibility in regard to prescribing controlled substances such as buprenorphine for OUD through 31 December 2024.[224]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "FDA approves first buprenorphine implant for treatment of opioid dependence". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 26 May 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "3 Patient Assessment". Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). 2004.

- ^ a b "Commonly Used Terms". www.cdc.gov. 29 August 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q American Psychiatric Association (2013), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.), Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing, pp. 540–546, ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8

- ^ a b c d Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration (30 September 2014). "Substance Use Disorders".

- ^ a b c "Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy". ACOG. August 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, Indave BI, Degenhardt L, Wiessing L, et al. (April 2017). "Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies". BMJ. 357: j1550. doi:10.1136/bmj.j1550. PMC 5421454. PMID 28446428.

- ^ a b "Treatment for Substance Use Disorders". Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. October 2014.

- ^ McDonald R, Strang J (July 2016). "Are take-home naloxone programmes effective? Systematic review utilizing application of the Bradford Hill criteria". Addiction. 111 (7): 1177–1187. doi:10.1111/add.13326. PMC 5071734. PMID 27028542.

- ^ a b c d Sharma B, Bruner A, Barnett G, Fishman M (July 2016). "Opioid Use Disorders". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 25 (3): 473–487. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2016.03.002. PMC 4920977. PMID 27338968.

- ^ a b c d e Dydyk AM, Jain NK, Gupta M (2022). "Opioid Use Disorder". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31985959. NCBI NBK553166. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration (30 September 2014). "Substance Use Disorders".

- ^ Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT (January 2016). "Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction". The New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (4): 363–371. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1511480. PMC 6135257. PMID 26816013.

Addiction: A term used to indicate the most severe, chronic stage of substance-use disorder, in which there is a substantial loss of self-control, as indicated by compulsive drug taking despite the desire to stop taking the drug. In the DSM-5, the term addiction is synonymous with the classification of severe substance-use disorder.

- ^ Webster LR (November 2017). "Risk Factors for Opioid-Use Disorder and Overdose". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 125 (5): 1741–1748. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000002496. PMID 29049118. S2CID 19635834.

- ^ Santoro TN, Santoro JD (December 2018). "Racial Bias in the US Opioid Epidemic: A Review of the History of Systemic Bias and Implications for Care". Cureus. 10 (12): e3733. doi:10.7759/cureus.3733. PMC 6384031. PMID 30800543.

- ^ Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration (30 September 2014). "Substance Use Disorders".

- ^ a b American Psychiatric Association (2013), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.), Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing, pp. 540–546, ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R (November 2022). "CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain - United States, 2022". MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 71 (3): 1–95. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1. PMC 9639433. PMID 36327391.

- ^ "A Prescriber's Guide to Medicare Prescription Drug (Part D) Opioid Policies" (PDF).

- ^ Mohamadi A, Chan JJ, Lian J, Wright CL, Marin AM, Rodriguez EK, et al. (August 2018). "Risk Factors and Pooled Rate of Prolonged Opioid Use Following Trauma or Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-(Regression) Analysis". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 100 (15): 1332–1340. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.01239. PMID 30063596. S2CID 51891341.

- ^ "Prescription opioid use is a risk factor for heroin use". National Institute on Drug Abuse. October 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ a b Hughes E (2 May 2018). "The Pain Hustlers". New York Times. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Trends in the Use of Methadone, Buprenorphine, and Extended-release Naltrexone at Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities: 2003–2015 (Update)". www.samhsa.gov. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ Donovan DM, Ingalsbe MH, Benbow J, Daley DC (2013). "12-step interventions and mutual support programs for substance use disorders: an overview". Social Work in Public Health. 28 (3–4): 313–332. doi:10.1080/19371918.2013.774663. PMC 3753023. PMID 23731422.

- ^ "Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs Providing Naloxone to Laypersons — United States, 2014". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. Arlington, VA : American Psychiatric Association. 2013. ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1.

- ^ CDC (30 August 2022). "Disease of the Week – Opioid Use Disorder". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ "Data Brief 294. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2016" (PDF). CDC. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ Malden DE, Hong V, Lewin BJ, Ackerson BK, Lipsitch M, Lewnard JA, et al. (24 June 2022). "Hospitalization and Emergency Department Encounters for COVID-19 After Paxlovid Treatment — California, December 2021–May 2022". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 71 (25): 830–833. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7125e2. ISSN 0149-2195. PMID 35737591.

- ^ Statistics Canada (2023). "Exploring the intersectionality of characteristics among those who experienced opioid overdoses: A cluster analysis". Health Reports. 34 (3). Government of Canada: 3–14. doi:10.25318/82-003-X202300300001-ENG. PMID 36921072.

- ^ Kosten TR, Haile CN. Opioid-Related Disorders. In: Kasper D, Fauci A, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J, Loscalzo J. eds. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 19e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2014. http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=1130§ionid=79757372 Accessed 9 March 2017.

- ^ Heidbreder C, Fudala PJ, Greenwald MK (2023). "History of the discovery, development, and FDA-approval of buprenorphine medications for the treatment of opioid use disorder". Drug and Alcohol Dependence Reports. 6. doi:10.1016/j.dadr.2023.100133. PMC 10040330. PMID 36994370.

- ^ James W. Kalat, Biological Psychology. Cengage Learning. Page 81.

- ^ EMEA 19 April 2001 EMEA Public Statement on the Recommendation to Suspend the Marketing Authorisation for Orlaam (Levacetylmethadol) in the European Union Archived 4 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Orlaam (levomethadyl acetate hydrochloride)". FDA Safety Alerts. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 20 August 2013. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017.

- ^ a b c Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT (January 2016). "Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction". The New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (4): 363–371. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1511480. PMC 6135257. PMID 26816013.

Addiction: A term used to indicate the most severe, chronic stage of substance-use disorder, in which there is a substantial loss of self-control, as indicated by compulsive drug taking despite the desire to stop taking the drug. In the DSM-5, the term addiction is synonymous with the classification of severe substance-use disorder.

- ^ Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (2006). "[Table], Figure 4-4: Signs and Symptoms of Opioid Intoxication and Withdrawal". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ Fentanyl. Image 4 of 17. US DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration). See archive with caption: "photo illustration of 2 milligrams of fentanyl, a lethal dose in most people".

- ^ Kosten TR, Haile CN. Opioid-Related Disorders. In: Kasper D, Fauci A, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J, Loscalzo J. eds. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 19e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2014. http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=1130§ionid=79757372 Accessed 9 March 2017.

- ^ Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5 (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. 2013. pp. 547–549. ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1.

- ^ a b Shah M, Huecker MR (2019). Opioid Withdrawal. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30252268. NCBI NBK526012. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ Pergolizzi JV, Raffa RB, Rosenblatt MH (October 2020). "Opioid withdrawal symptoms, a consequence of chronic opioid use and opioid use disorder: Current understanding and approaches to management". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 45 (5): 892–903. doi:10.1111/jcpt.13114. PMID 31986228.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ries RK, Miller SC, Fiellin DA (2009). Principles of Addiction Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 593–594. ISBN 978-0-7817-7477-2.

- ^ Rahimi-Movaghar A, Gholami J, Amato L, Hoseinie L, Yousefi-Nooraie R, Amin-Esmaeili M (June 2018). "Pharmacological therapies for management of opium withdrawal". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (6): CD007522. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007522.pub2. PMC 6513031. PMID 29929212.

- ^ Chen KW, Banducci AN, Guller L, Macatee RJ, Lavelle A, Daughters SB, et al. (November 2011). "An examination of psychiatric comorbidities as a function of gender and substance type within an inpatient substance use treatment program". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 118 (2–3): 92–99. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.003. PMC 3188332. PMID 21514751.

- ^ Webster LR, Webster RM (2005). "Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the Opioid Risk Tool". Pain Medicine. 6 (6): 432–442. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.00072.x. PMID 16336480.

- ^ Papaleontiou M, Henderson CR, Turner BJ, Moore AA, Olkhovskaya Y, Amanfo L, et al. (July 2010). "Outcomes associated with opioid use in the treatment of chronic noncancer pain in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 58 (7): 1353–1369. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02920.x. PMC 3114446. PMID 20533971.

- ^ a b Noble M, Tregear SJ, Treadwell JR, Schoelles K (February 2008). "Long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and safety". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 35 (2): 214–228. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.03.015. PMID 18178367.

- ^ Martell BA, O'Connor PG, Kerns RD, Becker WC, Morales KH, Kosten TR, et al. (January 2007). "Systematic review: opioid treatment for chronic back pain: prevalence, efficacy, and association with addiction". Annals of Internal Medicine. 146 (2): 116–127. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-146-2-200701160-00006. PMID 17227935. S2CID 28969290.

- ^ Kalso E, Edwards JE, Moore AR, McQuay HJ (December 2004). "Opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: systematic review of efficacy and safety". Pain. 112 (3): 372–380. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.019. PMID 15561393. S2CID 25807828.

- ^ a b Goesling J, DeJonckheere M, Pierce J, Williams DA, Brummett CM, Hassett AL, et al. (May 2019). "Opioid cessation and chronic pain: perspectives of former opioid users". Pain. 160 (5): 1131–1145. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001493. PMC 8442035. PMID 30889052.

- ^ Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, Jensen AC, DeRonne B, Goldsmith ES, et al. (March 2018). "Effect of Opioid vs Nonopioid Medications on Pain-Related Function in Patients With Chronic Back Pain or Hip or Knee Osteoarthritis Pain: The SPACE Randomized Clinical Trial". JAMA. 319 (9): 872–882. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0899. PMC 5885909. PMID 29509867.

- ^ Eriksen J, Sjøgren P, Bruera E, Ekholm O, Rasmussen NK (November 2006). "Critical issues on opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: an epidemiological study". Pain. 125 (1–2): 172–179. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.06.009. PMID 16842922. S2CID 24858908.

- ^ Chaparro LE, Furlan AD, Deshpande A, Mailis-Gagnon A, Atlas S, Turk DC (April 2014). "Opioids compared with placebo or other treatments for chronic low back pain: an update of the Cochrane Review". Spine. 39 (7): 556–563. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000249. PMID 24480962. S2CID 25356400.

- ^ a b Regmi S, Kedia SK, Ahuja NA, Lee G, Entwistle C, Dillon PJ (July 2024). "Association Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Opioid Use-Related Behaviors: A Systematic Review". Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 25 (3): 2046–2064. doi:10.1177/15248380231205821. ISSN 1524-8380. PMID 37920999.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nestler EJ (December 2013). "Cellular basis of memory for addiction". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 15 (4): 431–443. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.4/enestler. PMC 3898681. PMID 24459410.

Despite the importance of numerous psychosocial factors, at its core, drug addiction involves a biological process.

- ^ a b c Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 364–375. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

- ^ a b "Glossary of Terms". Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Department of Neuroscience. Archived from the original on 10 May 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ a b Schultz W (July 2015). "Neuronal Reward and Decision Signals: From Theories to Data". Physiological Reviews. 95 (3): 853–951. doi:10.1152/physrev.00023.2014. PMC 4491543. PMID 26109341.

- ^ Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (13 March 2019). "The Biology of Addiction". YouTube.

- ^ Gold MS, Baron D, Bowirrat A, Blum K (15 September 2020). "Neurological correlates of brain reward circuitry linked to opioid use disorder (OUD): Do homo sapiens acquire or have a reward deficiency syndrome?". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 418 (117137). doi:10.1016/j.jns.2020.117137. PMC 7490287. PMID 32957037.

- ^ Robinson TE, Berridge KC (October 2008). "Review. The incentive sensitization theory of addiction: some current issues". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 363 (1507): 3137–3146. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0093. PMC 2607325. PMID 18640920.

- ^ a b "Opioid Use Disorder".

- ^ "Medically Supervised Withdrawal (Detoxification) from Opioids". pcssnow.org. 11 June 2021.

- ^ Weiss RD, Potter JS, Fiellin DA, Byrne M, Connery HS, Dickinson W, et al. (December 2011). "Adjunctive counseling during brief and extended buprenorphine-naloxone treatment for prescription opioid dependence: a 2-phase randomized controlled trial". Archives of General Psychiatry. 68 (12): 1238–1246. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.121. PMC 3470422. PMID 22065255.

- ^ a b Robison AJ, Nestler EJ (October 2011). "Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 12 (11): 623–637. doi:10.1038/nrn3111. PMC 3272277. PMID 21989194.

- ^ a b Olsen CM (December 2011). "Natural rewards, neuroplasticity, and non-drug addictions". Neuropharmacology. 61 (7): 1109–1122. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.010. PMC 3139704. PMID 21459101.

- ^ a b Ruffle JK (November 2014). "Molecular neurobiology of addiction: what's all the (Δ)FosB about?". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 40 (6): 428–437. doi:10.3109/00952990.2014.933840. PMID 25083822. S2CID 19157711.

- ^ Blum K, Werner T, Carnes S, Carnes P, Bowirrat A, Giordano J, et al. (2012). "Sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll: hypothesizing common mesolimbic activation as a function of reward gene polymorphisms". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 44 (1): 38–55. doi:10.1080/02791072.2012.662112. PMC 4040958. PMID 22641964.

- ^ a b Bourdy R, Barrot M (November 2012). "A new control center for dopaminergic systems: pulling the VTA by the tail". Trends in Neurosciences. 35 (11): 681–690. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2012.06.007. PMID 22824232. S2CID 43434322.

- ^ a b "Morphine addiction – Homo sapiens (human)". KEGG. Kanehisa Laboratories. 18 June 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ^ a b Mistry CJ, Bawor M, Desai D, Marsh DC, Samaan Z (May 2014). "Genetics of Opioid Dependence: A Review of the Genetic Contribution to Opioid Dependence". Current Psychiatry Reviews. 10 (2): 156–167. doi:10.2174/1573400510666140320000928. PMC 4155832. PMID 25242908.

- ^ Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND (October 2011). "Dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex in addiction: neuroimaging findings and clinical implications". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 12 (11): 652–669. doi:10.1038/nrn3119. PMC 3462342. PMID 22011681.

- ^ Schoenbaum G, Shaham Y (February 2008). "The role of orbitofrontal cortex in drug addiction: a review of preclinical studies". Biological Psychiatry. 63 (3): 256–262. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.003. PMC 2246020. PMID 17719014.

- ^ Ieong HF, Yuan Z (1 January 2017). "Resting-State Neuroimaging and Neuropsychological Findings in Opioid Use Disorder during Abstinence: A Review". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 11: 169. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2017.00169. PMC 5382168. PMID 28428748.

- ^ a b c d Nestler EJ (August 2016). "Reflections on: "A general role for adaptations in G-Proteins and the cyclic AMP system in mediating the chronic actions of morphine and cocaine on neuronal function"". Brain Research. 1645: 71–74. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2015.12.039. PMC 4927417. PMID 26740398.

Specifically, opiates in several CNS regions including NAc, and cocaine more selectively in NAc induce expression of certain adenylyl cyclase isoforms and PKA subunits via the transcription factor, CREB, and these transcriptional adaptations serve a homeostatic function to oppose drug action. In certain brain regions, such as locus coeruleus, these adaptations mediate aspects of physical opiate dependence and withdrawal, whereas in NAc they mediate reward tolerance and dependence that drives increased drug self-administration.

- ^ a b "Opioid Use Disorder: Diagnostic Criteria". Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (PDF). American Psychiatric Association. pp. 1–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ Vargas-Perez H, Ting-A Kee R, Walton CH, Hansen DM, Razavi R, Clarke L, et al. (June 2009). "Ventral tegmental area BDNF induces an opiate-dependent-like reward state in naive rats". Science. 324 (5935): 1732–1734. Bibcode:2009Sci...324.1732V. doi:10.1126/science.1168501. PMC 2913611. PMID 19478142.

- ^ Laviolette SR, van der Kooy D (March 2001). "GABA(A) receptors in the ventral tegmental area control bidirectional reward signalling between dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic neural motivational systems". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 13 (5): 1009–1015. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9568.2001.01458.x. PMID 11264674. S2CID 46694281.

- ^ a b c Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C (March 2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831. S2CID 5903121.

- ^ a b c Dick DM, Agrawal A (2008). "The genetics of alcohol and other drug dependence". Alcohol Research & Health. 31 (2): 111–118. PMC 3860452. PMID 23584813.

- ^ Hall FS, Drgonova J, Jain S, Uhl GR (December 2013). "Implications of genome wide association studies for addiction: are our a priori assumptions all wrong?". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 140 (3): 267–279. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.07.006. PMC 3797854. PMID 23872493.

- ^ a b Bruehl S, Apkarian AV, Ballantyne JC, Berger A, Borsook D, Chen WG, et al. (February 2013). "Personalized medicine and opioid analgesic prescribing for chronic pain: opportunities and challenges". The Journal of Pain. 14 (2): 103–113. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2012.10.016. PMC 3564046. PMID 23374939.

- ^ a b Khokhar JY, Ferguson CS, Zhu AZ, Tyndale RF (2010). "Pharmacogenetics of drug dependence: role of gene variations in susceptibility and treatment". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 50: 39–61. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105826. PMID 20055697. S2CID 2158248.

- ^ a b Solhaug V, Molden E (October 2017). "Individual variability in clinical effect and tolerability of opioid analgesics - Importance of drug interactions and pharmacogenetics". Scandinavian Journal of Pain. 17: 193–200. doi:10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.09.009. PMID 29054049.

- ^ "CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain | Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center". www.cdc.gov. 31 August 2018. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ^ Wakeman S, Larochelle M, Ameli O (2020). "Comparative Effectiveness of Different Treatment Pathways for Opioid Use Disorder". JAMA Network Open. 3 (2): e1920622. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622. PMC 11143463. PMID 32022884. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ McCarty D, Priest KC, Korthuis PT (1 April 2018). "Treatment and Prevention of Opioid Use Disorder: Challenges and Opportunities". Annual Review of Public Health. 39 (1): 525–541. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013526. ISSN 0163-7525. PMC 5880741. PMID 29272165.

- ^ "Our Commitment to Fight Opioid Abuse | CVS Health". CVS Health. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ^ "Combat opioid abuse | Walgreens". Walgreens. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ^ a b "Naloxone for Treatment of Opioid Overdose" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ "Prevent Opioid Use Disorder | Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center". www.cdc.gov. 31 August 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ McCarty D, Priest KC, Korthuis PT (April 2018). "Treatment and Prevention of Opioid Use Disorder: Challenges and Opportunities". Annual Review of Public Health. 39 (1): 525–541. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013526. PMC 5880741. PMID 29272165.

- ^ "Naloxone". Human Metabolome Database – Version 4.0. 23 October 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^ "Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs Providing Naloxone to Laypersons — United States, 2014". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ Childs R (July 2015). "Law enforcement and naloxone utilization in the United States" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition. pp. 1–24. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^ "Case studies: Standing orders". NaloxoneInfo.org. Open Society Foundations. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Schuckit MA (July 2016). "Treatment of Opioid-Use Disorders". The New England Journal of Medicine. 375 (4): 357–368. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1604339. PMID 27464203.

- ^ Christie C, Baker C, Cooper R, Kennedy CP, Madras B, Bondi FA. The president's commission on combating drug addiction and the opioid crisis. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, November 2017;1.

- ^ "Naloxone Opioid Overdose Reversal Medication". CVS Health. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ a b Morin KA, Vojtesek F, Acharya S, Dabous JR, Marsh DC (October 2021). "Evidence of Increased Age and Sex Standardized Death Rates Among Individuals Who Accessed Opioid Agonist Treatment Before the Era of Synthetic Opioids in Ontario, Canada". Cureus. 13 (10): e19051. doi:10.7759/cureus.19051. PMC 8608679. PMID 34853762.

- ^ Hser YI, Hoffman V, Grella CE, Anglin MD (May 2001). "A 33-year follow-up of narcotics addicts". Archives of General Psychiatry. 58 (5): 503–508. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.503. PMID 11343531.

- ^ Horon IL, Singal P, Fowler DR, Sharfstein JM (June 2018). "Standard Death Certificates Versus Enhanced Surveillance to Identify Heroin Overdose-Related Deaths". American Journal of Public Health. 108 (6): 777–781. doi:10.2105/ajph.2018.304385. PMC 5944879. PMID 29672148.

- ^ "Abuse-Deterrent Opioid Analgesics". Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2 March 2021.

- ^ Spence C, Kurz ME, Sharkey TC, Miller BL (23 June 2024). "Scoping Literature Review of Disease Modeling of the Opioid Crisis". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs: 1–14. doi:10.1080/02791072.2024.2367617. ISSN 0279-1072. PMID 38909286.

- ^ "Treatment of opioid dependence". WHO. 2004. Archived from the original on 14 June 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2016.[needs update]

- ^ Amato L, Davoli M, Minozzi S, Ferroni E, Ali R, Ferri M (February 2013). "Methadone at tapered doses for the management of opioid withdrawal". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (2): CD003409. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003409.pub4. PMC 7017622. PMID 23450540.

- ^ MacArthur GJ, van Velzen E, Palmateer N, Kimber J, Pharris A, Hope V, et al. (January 2014). "Interventions to prevent HIV and Hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: a review of reviews to assess evidence of effectiveness". The International Journal on Drug Policy. 25 (1): 34–52. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.07.001. PMID 23973009.

- ^ Nielsen S, Tse WC, Larance B, et al. (Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group) (September 2022). "Opioid agonist treatment for people who are dependent on pharmaceutical opioids". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (9): CD011117. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011117.pub3. PMC 9443668. PMID 36063082.

- ^ "Opioid substitution therapy or treatment (OST)". Migration and Home Affairs. European Commission. 14 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Richard P. Mattick et al.: National Evaluation of Pharmacotherapies for Opioid Dependence (NEPOD): Report of Results and Recommendation

- ^ Whelan PJ, Remski K (January 2012). "Buprenorphine vs methadone treatment: A review of evidence in both developed and developing worlds". Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice. 3 (1): 45–50. doi:10.4103/0976-3147.91934. PMC 3271614. PMID 22346191.

- ^ Martin JA, Campbell A, Killip T, Kotz M, Krantz MJ, Kreek MJ, et al. (October 2011). "QT interval screening in methadone maintenance treatment: report of a SAMHSA expert panel". Journal of Addictive Diseases. 30 (4): 283–306. doi:10.1080/10550887.2011.610710. PMC 4078896. PMID 22026519.

- ^ https://www.bccsu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/BC-OUD-Treatment-Guideline_2023-Update.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "MAT Medications, Counseling, and Related Conditions". www.samhsa.gov. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ "Methadone". www.samhsa.gov. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ a b c "Waiver Elimination (MAT Act)". 10 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT)". www.samhsa.gov. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ Gowing L, Farrell M, Ali R, White JM (May 2016). "Alpha₂-adrenergic agonists for the management of opioid withdrawal". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (5): CD002024. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002024.pub5. PMC 7081129. PMID 27140827.

- ^ Michels II, Stöver H, Gerlach R (February 2007). "Substitution treatment for opioid addicts in Germany". Harm Reduction Journal. 4 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-4-5. PMC 1797169. PMID 17270059.

- ^ "Many hospital policies create barriers to good management of opioid withdrawal". NIHR Evidence. 16 November 2022. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_54639. S2CID 253608569.

- ^ Harris M, Holland A, Lewer D, Brown M, Eastwood N, Sutton G, et al. (April 2022). "Barriers to management of opioid withdrawal in hospitals in England: a document analysis of hospital policies on the management of substance dependence". BMC Medicine. 20 (1): 151. doi:10.1186/s12916-022-02351-y. PMC 9007696. PMID 35418095.