New York Dolls (album)

| New York Dolls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | July 27, 1973 | |||

| Recorded | April 1973 | |||

| Studio | The Record Plant (New York) | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 42:44 | |||

| Label | Mercury | |||

| Producer | Todd Rundgren | |||

| New York Dolls chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from New York Dolls | ||||

| ||||

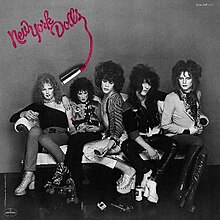

New York Dolls is the debut album by the American hard rock band New York Dolls. It was released on July 27, 1973, by Mercury Records. In the years leading up to the album, the Dolls had developed a local fanbase by playing regularly in lower Manhattan after forming in 1971. However, most music producers and record companies were reluctant to work with them because of their vulgarity and onstage fashion as well as homophobia in New York; the group later appeared in exaggerated drag on the album cover for shock value.

After signing a contract with Mercury, the Dolls recorded their first album at The Record Plant in New York City with producer Todd Rundgren, who was known for his sophisticated pop tastes and held a lukewarm opinion of the band. Despite stories of conflicts during the recording sessions, lead singer David Johansen and guitarist Sylvain Sylvain later said Rundgren successfully captured how the band sounded live. The resulting music on the album – a mix of carefree rock and roll, influences from Brill Building pop, and campy sensibilities – explores themes of urban youth, teen alienation, adolescent romance, and authenticity, as rendered in Johansen's colloquial and ambiguous lyrics.

New York Dolls was met with widespread critical acclaim but sold poorly and polarized listeners. The band proved difficult to market outside their native New York and developed a reputation for rock-star excesses while touring the United States in support of the album. Despite its commercial failure, New York Dolls was an influential precursor to the 1970s punk rock movement as the group's crude musicianship and youthful attitude on the album challenged the prevailing trend of musical sophistication in popular music, particularly progressive rock. Among the most acclaimed albums in history, it has since been named in various publications as one of the best debut records in rock music and one of the greatest albums of all time.

Background[edit]

In 1971, vocalist David Johansen formed the New York Dolls with guitarists Johnny Thunders and Rick Rivets, bassist Arthur Kane, and drummer Billy Murcia; Rivets was replaced by Sylvain Sylvain in 1972.[1] The band was meant to be a temporary project for the members, who were club-going youths that had gone to New York City with different career pursuits. As Sylvain recalled, "We just said 'Hey, maybe this will get us some chicks.' That seemed like a good enough reason." He and Murcia originally planned to work in the clothing business and opened a boutique on Lexington Avenue that was across the street from a toy repair shop called the New York Doll Hospital, which gave them the idea for their name.[2] The group soon began playing regularly in lower Manhattan and earned a cult following within a few months with their reckless style of rock music. Nonetheless, record companies were hesitant to sign them because of their onstage cross-dressing and blatant vulgarity.[1]

Clive Davis once told Lisa Robinson not to talk about New York Dolls uptown if she wanted to work in the music biz. They were petrified of the Dolls. They thought they were homosexual. It wasn't just homophobia; it was still illegal to be homosexual. People don't remember that it was the law. To say the Dolls, guys who wore makeup, were your friends was like saying you knew a criminal.

In October 1972, the group garnered the interest of critics when they opened for English rock band the Faces at the Empire Pool in Wembley.[4] However, on the New York Dolls' first tour of England that year, Murcia died after consuming a lethal combination of alcohol and methaqualone.[5] They enlisted Jerry Nolan as his replacement, while managers Marty Thau, Steve Leber, and David Krebs still struggled to find the band a record deal.[4]

After returning to New York, the Dolls played to capacity crowds at venues such as Max's Kansas City and the Mercer Arts Center in what Sylvain called a determined effort to "fake it until they could make it": "We had to make ourselves feel famous before we could actually become famous. We acted like we were already rock stars. Arthur even called his bass 'Excalibur' after King Arthur. It was crazy."[4] Their performance at the Mercer Arts Center was attended by journalist and Mercury Records publicity director Bud Scoppa, and Paul Nelson, an A&R executive for the label. Scoppa initially viewed them as an amusing but inferior version of the Rolling Stones: "I split after the first set. Paul stuck around for the second set, though, and after the show he called me and said, 'You should have stayed. I think they're really special.' Then, after that, I fell in love with them anyway."[6] In March 1973, the group signed a two-album deal with a US $25,000 advance from Mercury.[7] According to Sylvain, some of the members' parents had to sign for them because they were not old enough to sign themselves.[6]

Hiring of Todd Rundgren[edit]

For the New York Dolls' debut album, Mercury wanted to find a record producer who could make the most out of the group's sound and the hype they had received from critics and fans in New York.[6] At the band's first board meeting in Chicago, Johansen fell asleep in Mercury's conference room while record executives discussed potential producers. He awoke when they mentioned Todd Rundgren, a musician and producer who by 1972 had achieved unexpected rock stardom with his double album Something/Anything? and its hit singles "I Saw the Light" and "Hello It's Me".[8] Rundgren had socialized at venues such as Max's Kansas City and first saw the Dolls when his girlfriend at the time, model Bebe Buell, brought him there to see them play.[4]

Known for having refined pop tastes and technologically savvy productions, Rundgren had become increasingly interested in progressive rock sounds by the time he was enlisted to produce the New York Dolls' debut album.[9] Consequently, his initial impression of the group was that of a humorous live act who were technically competent only by the standards of other unsophisticated New York bands. "The Dolls weren't out to expand any musical horizons", said Rundgren, although he enjoyed Thunders' "attitude" and Johansen's charismatic antics onstage.[10] Johansen had thought of Rundgren as "an expert on second rate rock 'n' roll", but also said the band was "kind of persona non grata, at the time, with most producers. They were afraid of us, I don't know why, but Todd wasn't. We all liked him from Max's ... Todd was cool and he was a producer."[11] Sylvain, on the other hand, felt the decision to enlist him was based on availability, time, and money: "It wasn't a long list. Todd was in New York and seemed like he could handle the pace."[12] Upon being hired, Rundgren declared that "the only person who can produce a New York record is someone who lives in New York".[13]

Recording and production[edit]

Mercury booked the Dolls at The Record Plant in New York City for recording sessions in April 1973.[14] Rundgren was originally concerned that they had taken "the worst sounding studio in the city at that time" because it was the only one available to them with the short time given to record and release the album. He later said that expectations for the band and the festive atmosphere of the recording sessions proved to be more of a problem: "The Dolls were critics' darlings and the press had kind of adopted them. Plus, there were lots of extra people around, socializing, which made it hard to concentrate."[12] New York Dolls was recorded there in eight days on a budget of $17,000 (equivalent to $117,000 in 2023).[15] With a short amount of studio time and no concept in mind for the album, the band chose which songs to record based on how well they had been received at their live shows.[16] In Johansen's own words, "we went into a room and just recorded. It wasn't like these people who conceptualize things. It was just a document of what was going on at the time."[17]

In the studio, the New York Dolls dressed in their usual flashy clothes. Rundgren, who did not approve of their raucous sound, at one point yelled at them during the sessions to "get the glitter out of your asses and play".[18] Sylvain recalled Rundgren inviting Buell and their Chihuahua to the studio and putting the latter atop an expensive mixing console, while Johansen acknowledged that his recollections of the sessions have since been distorted by what he has read about them: "It was like the 1920s, with palm tree décor and stuff. Well, that's how I remember it, anyway."[12] He also said Rundgren directed the band from the control room with engineer Jack Douglas and hardly spoke to them while they recorded the album.[19] According to Scoppa, the group's carefree lifestyle probably conflicted with Rundgren's professional work ethic and schedule: "He doesn't put up with bullshit. I mean, [the band] rarely started their live sets before midnight, so who knows? Todd was very much in charge in the studio, however, and I got the impression that everybody was looking to him."[20]

I think [Todd] was actually quite taken that we obviously derived our talent from the streets. We may not have been professionally trained, but we could still write three minutes worth of magic. He probably played with other well-seasoned players who may have graduated from Juilliard or worked with the orchestra pit, but could they write a damn good fucking tune? Todd knew we were writing tunes for our generation.

— Sylvain Sylvain (2009)[19]

Although Sylvain said Rundgren was not an interfering producer, he occasionally involved himself to improve a take. Sylvain recalled moments when Rundgren went into the isolation booth with Nolan when he struggled keeping a beat and drummed out beats on a cowbell for him to use as a click track. During another session, he stopped a take and walked out of the control room to plug in Kane's bass cabinet.[19] Scoppa, who paid afternoon visits to the studio, overheard Rundgren say, "Yeah, that's all you needed. Okay, let's try it again!", and ultimately found the exchange funny and indicative of Rundgren's opinion of the band: "Todd was such a 'musician' while they were just getting by on attitude and energy. But as disdainful as he appeared to be at some points he got the job done really well."[19] Rundgren felt Johansen's wild singing often sounded screamed or drunken but also eloquent in the sense that Johansen demonstrated a "propensity to incorporate certain cultural references into the music", particularly on "Personality Crisis". While recording the song, Johansen walked back into the control room and asked Rundgren if his vocals sounded "ludicrous enough".[19]

Because the Dolls had little money, Sylvain and Thunders played the austerely designed and affordable Gibson Les Paul Junior guitars on the record. They jokingly referred to them as "automatic guitars" due to their limited sound shaping features. To amplify their guitars, they ran a Marshall Plexi standalone amplifier through the speaker cabinets of a Fender Dual Showman, and occasionally used a Fender Twin Reverb.[19]

Some songs were embellished with additional instruments, including Buddy Bowser's brassy saxophone on "Lonely Planet Boy".[20] Johansen sang into distorted guitar pickups for additional vocals and overdubbed them into the song. He also played an Asian gong for "Vietnamese Baby" and harmonica on "Pills". For "Personality Crisis", Sylvain originally played on The Record Plant's Yamaha grand piano before Rundgren added his own piano flourishes to both that song and "Private World".[21] Rundgren also contributed to the background vocals heard on "Trash" and played synthesizers on "Vietnamese Baby" and "Frankenstein (Orig.)", which Sylvain recalled: "I remember him getting those weird sounds from this beautiful old Moog synthesizer he brought in. He said it was a model that only he and the Beatles had."[21]

New York Dolls was mixed in less than half a day.[22] Rundgren felt the band seemed distracted and disinterested at that point, so he tried unsuccessfully to ban them from the mixing session.[21] For the final mix, he minimized the sound of Nolan's drumming.[18] In retrospect, Rundgren said the quality of the mix was poor because the band had hurried and questioned him while mixing the record: "It's too easy for it to become a free-for-all, with every musician only hearing their own part and not the whole. They all had other places to be, so rather than split, they rushed the thing and if that wasn't enough they took it to the crappy mastering lab that Mercury had put them in."[21] Thunders famously complained to a journalist that Rundgren "fucked up the mix" on New York Dolls, adding to stories that the two had clashed during the album's recording.[20] Both Johansen and Scoppa later said they did not see any conflict between the two and that Thunders' typically foolish behavior was misinterpreted.[20] Johansen later praised Rundgren for how he enhanced and equalized each instrument, giving listeners the impression that "[they're] in a room and there's a band playing", while Sylvain said his mix accurately captured how the band sounded live.[21]

Music and lyrics[edit]

New York Dolls features ten original songs and one cover – the 1963 Bo Diddley song "Pills".[22] Johansen describes the album as "a little jewel of urban folk art".[18] Rundgren, on the other hand, says the band's sensibilities were different from "the urban New York thing" because they had been raised outside Manhattan and drew on carefree rock and roll and Brill Building pop influences such as the Shangri-Las: "Their songs, as punky as they were, usually had a lot to do with the same old boy-girl thing but in a much more inebriated way."[6] Johansen quotes the lyric "when I say I'm in love, you'd best believe I'm in love L-U-V" from the Shangri-Las' "Give Him a Great Big Kiss" (1964) when opening "Looking for a Kiss", which tells a story of adolescent romantic desire hampered by peers who use drugs.[23] On "Subway Train", he uses lyrics from the American folk standard "Someone's in the Kitchen with Dinah".[24] In the opinion of critic Stephen Thomas Erlewine, the album's rowdy hard rock songs also revamp riffs from Chuck Berry and the Rolling Stones, resulting in music that sounds edgy and threatening in spite of the New York Dolls' wittingly kitsch and camp sensibilities.[25] "Personality Crisis" features raunchy dual guitars, boogie-woogie piano, and a histrionic pause, while "Trash" is a punky pop rock song with brassy singing.[26]

Several songs on New York Dolls function as what Robert Hilburn deems to be "colorful, if exaggerated, expressions of teen alienation".[27] According to Robert Christgau, because many of Manhattan's white youths at the time were wealthy and somewhat artsy, only ill-behaved young people from the outer boroughs like the band could "capture the oppressive excitement Manhattan holds for a half-formed human being".[28] "Private World", an escapist plea for stability, was co-written by Kane, who rarely contributed as a songwriter and felt overwhelmed as a young adult in the music business.[29] Sylvain jokingly says "Frankenstein (Orig.)" was titled with the parenthetical qualifier because rock musician Edgar Winter had released his song of the same name before the band could record their own: "Our song 'Frankenstein' was a big hit in our live show ... Now, his thing didn't sound at all like ours, but I'm sure he stole our title."[6] Johansen, the band's main lyricist, says "Frankenstein (Orig.)" is about "how kids come to Manhattan from all over, they're kind of like whipped dogs, they're very repressed. Their bodies and brains are disoriented from each other ... it's a love song."[30] In interpreting the song's titular monster, Frank Kogan writes that it serves as a personification for New York and its ethos, while Johansen asking listeners if they "could make it with Frankenstein" involves more than sexual slang:

Frankenstein wasn't just a creature to have sex with, he represented the whole funky New Yorkiness of New York, the ostentation and the terror, the dreams and the fear ... David was asking if you – if I – could make it with the monster of life, whether I could embrace life in all its pain and dreams and disaster.[31]

Although the Dolls exhibit tongue-in-cheek qualities, Gary Graff observes a streetwise realism in the album's songs.[32] In Christgau's opinion, Johansen's colloquial and morally superior lyrics are imbued with humor and a sense of human limits in songs whose fundamental theme is authenticity. This theme is explored in stories about lost youths, as on "Subway Train", or in a study of a specific subject, such as the "schizy imagemonger" on "Personality Crisis".[33] He argues that beneath the band's decadent and campy surface are lyrics about "the modern world ... one nuclear bomb could blow it all away. Pills and personality crises weren't evils – easy, necessary, or whatever. They were strategies and tropisms and positive pleasures".[34] According to journalist Steve Taylor, "Vietnamese Baby" deals with the impact of the Vietnam War at the time on everyday activities for people, whose fun is undermined by thoughts of collective guilt.[35]

On songs such as "Subway Train" and "Trash", Johansen uses ambiguity as a lyrical mode.[36] In Kogan's opinion, Johansen sings in an occasionally unintelligible manner and writes in a perplexing, fictional style that is lazy yet ingenious, as it provides his lyrics an abundance of "emotional meaning" and interpretation: "David never provides an objective framework, he's always jumping from voice to voice, so you're hearing a character addressing another character, or the narrator addressing the character, or the character or the narrator addressing us, all jammed up together so you're hearing bits of conversation and bits of subjective description in no kind of chronological order. But as someone says in 'Vietnamese Baby': 'Everything connects.'"[37] On "Trash", Johansen undercuts his vaguely pansexual beliefs with the possibility of going to "fairyland" if he takes a "lover's leap" with the song's subject.[34]

Marketing and sales[edit]

New York Dolls was released on July 27, 1973, in the United States and on October 19 in the United Kingdom.[38] Its controversial cover featured the band dressed in exaggerated drag, including high wigs, messy make-up, high heels, and garters.[22] The photo was used for shock value, and on the back of the album, the band is photographed in their usual stage wear.[39] To announce the album's release, Mercury published an advertisement slogan that read "Introducing The New York Dolls: A Band You're Gonna Like, Whether You Like It Or Not", while other ads called them "The Band You Love to Hate".[40] Two double A-sided, 7-inch singles were released – "Trash" / "Personality Crisis" in July and "Jet Boy" / "Vietnamese Baby" in November 1973 – neither of which charted.[41]

New York Dolls was commercially unsuccessful and only reached number 116 on the American Top LPs while in the UK it failed to chart altogether.[42] The record sold over 100,000 copies at the time and fell well short of expectations in the press.[43] According to Rolling Stone in 2003, it ended up selling fewer than 500,000 copies.[44] Music journalist Phil Strongman said its commercial failure could be attributed to the New York Dolls' divisive effect on listeners, including writers from the same magazine.[45] In a feature story on the band for Melody Maker prior to the album, Mark Plummer had dismissed their playing as the poorest he had ever seen, while the magazine's reporter Michael Watts viewed them as an encouraging albeit momentary presence in what he felt was a lifeless rock and roll scene at the time.[46] In Creem's readers poll, the album earned the band awards in the categories of "Best New Group of the Year" and "Worst New Group of the Year".[47]

After the album's release, the Dolls toured the US as a supporting act for English rock band Mott the Hoople. Reviews complimented their songwriting, Thunders and Sylvain's guitar interplay, and noted their campy fashion and the resemblance of Johansen and Thunders to Mick Jagger and Keith Richards. However, some critics panned them as an unserious group of amateurs who could not play or sing.[48] During their appearance on The Old Grey Whistle Test in the UK, the show's host Bob Harris dismissed their music as "mock rock" in his on-air comments.[49] They also developed a reputation for rock-star excesses, including drugs, groupies, trashed hotel rooms, and public disturbances, and according to Ben Edmonds of Creem, became "the most walked-out-on band in the history of show business".[50] Strongman wrote that the band and the album were difficult to market because of their kitschy style and how Murcia's death had exacerbated their association with hard drugs, which "wasn't altogether true in the early days".[51] They remained the most popular band in New York City, where their Halloween night concert at the Waldorf Astoria in 1973 drew hundreds of young fans and local television coverage.[52]

Critical reception and legacy[edit]

New York Dolls received widespread acclaim from contemporary reviewers.[53] In a rave review for NME, published in August 1973, Nick Kent said the band's raunchy style of rock and roll had been vividly recorded by Rundgren on an album that, besides Iggy and the Stooges' Raw Power (1973), serves as the only one "so far to fully define just exactly where 1970s rock should be coming from".[54] Trouser Press founder and editor Ira Robbins viewed New York Dolls as an innovative record, brilliantly chaotic, and well produced by Rundgren.[54] Ellen Willis, writing for The New Yorker, said it is by far 1973's most compelling hard rock album and that at least half of its songs are immediate classics, particularly "Personality Crisis" and "Trash", which she called "transcendent".[55] In Newsday, Christgau hailed the New York Dolls as "the best hard rock band in the country and maybe the world right now", writing that their "special genius" is combining the shrewd songwriting savvy of early-1960s pop with the anarchic sound of late-1960s heavy metal. He claimed that the record's frenzied approach, various emotions, and wild noise convey Manhattan's harsh, deviant thrill better than the Velvet Underground.[56]

In an overall positive review, Rolling Stone critic Tony Glover found the band's impressive live sound to be mostly preserved on the album. However, he was slightly critical of production flourishes and overdubs, feeling that they make some lyrics sound incomprehensible and some choruses too sonorous. Although he was surprised at how well Rundgren's production works with the group's raunchy sound on most of the songs, Glover ultimately asked whether or not "the record alone will impress as much as seeing them live (they're a highly watchable group)."[57] Years later, Christgau would also voice that the album is "in fact a little botched aurally", but still regarded it as a classic.[58]

Impact and reappraisal[edit]

Until the New York Dolls a hangover from the sixties had permeated the music scene. That album was where a new decade began, where a contemporary version of the essence of rock 'n' roll emerged to kick out the tired old men and clear the way for the New Order.

— Tony Parsons (1977)[59]

New York Dolls is often cited as one of the greatest debut albums in rock music, one of the genre's most popular cult records, and a foundational work for the late 1970s punk rock movement.[60] Chuck Eddy considers it one of the records crucial to rock's evolution.[61] The album was a pivotal influence on many of the rock and roll, punk, and glam rock groups that followed, including the Ramones, Kiss, the Sex Pistols, the Damned, and Guns N' Roses.[62] Chris Smith, in 101 Albums That Changed Popular Music (2009), says that the New York Dolls's pioneering punk aesthetic of amateurish musicianship on the album undermined the musical sophistication that developed in the preceding years of popular music and was perfected months earlier with Pink Floyd's The Dark Side of the Moon (1973).[63] Similarly, The Guardian publication "1000 albums to hear before you die" credits New York Dolls for serving as "an efficacious antidote to the excesses of prog rock".[64]

According to Sylvain, the album's influence on punk can be attributed to how Rundgren recorded Sylvain's guitar through the left speaker and Thunders' guitar on the right side, an orientation younger bands such as the Ramones and the Sex Pistols subsequently adopted.[21] Rundgren, on the other hand, was amused by how the record became considered a precursor to the punk movement: "The irony is that I wound up producing the seminal punk album, but I was never really thought of as a punk producer, and I never got called by punk acts. They probably thought I was too expensive for what they were going for. But the Dolls didn't really consider themselves punk."[54] It was English singer Morrissey's favorite album, and according to Paul Myers, the record "struck such a chord with [him] that he was not only moved to form his own influential group, The Smiths ... but would eventually convince the surviving Dolls to reunite [in 2004]".[65]

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Chicago Sun-Times | |

| Christgau's Record Guide | A+[28] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Los Angeles Times | |

| MusicHound Rock | 3.5/5[68] |

| The New Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Spin Alternative Record Guide | 10/10[72] |

According to The Mojo Collection (2007), New York Dolls ignited punk rock and could still inspire more movements because of the music's abundant attitude and passion, while Encyclopedia of Popular Music writer Colin Larkin deems it "a major landmark in rock history, oozing attitude, vitality and controversy from every note".[73] Writing for AllMusic, Erlewine – the website's senior editor – claims that New York Dolls is a more quintessential proto-punk album than any of the Stooges' releases because of how it "plunders history while celebrating it, creating a sleazy urban mythology along the way".[25] David Fricke considers it to be a more definitive glam rock album than David Bowie's Ziggy Stardust (1972) or anything by Marc Bolan because of how the band "captured both the glory and sorrow of glam, the high jinx and wasted youth, with electric photorealism".[70] In The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (2004), Joe Gross calls it an "absolutely essential" record and "epic sleaze, the sound of five young men shaping the big city in their own scuzzy image".[74]

Professional rankings[edit]

New York Dolls appears frequently on professional listings of the greatest albums. In 1978, it was voted 199th in Paul Gambaccini's book Rock Critics' Choice: The Top 200 Albums, which polled a number of leading music journalists and record collectors.[75] Christgau, one of the critics polled, ranked it as the 15th best album of the 1970s in The Village Voice the following year – 11 spots behind the Dolls' second album Too Much Too Soon (1974), although years later he would say the first album should be ranked ahead and was his favorite rock album.[76] New York Dolls was included in Neil Strauss's 1996 list of the 100 most influential alternative records, and the Spin Alternative Record Guide (1995) named it the 70th best alternative album.[77] In 2002, it was included on a list published by Q of the 100 best punk records, while Mojo named it both the 13th greatest punk album and the 49th greatest album of all time.[78] Rolling Stone placed the record at number 213 on its 500 greatest albums list in 2003 and "Personality Crisis" at number 271 on its 500 greatest songs list the following year.[79][nb 1] In 2007, Mojo polled a panel of prominent recording artists and songwriters for the magazine's "100 Records That Changed the World" publication, in which New York Dolls was voted the 39th most influential and inspirational record ever.[81] In 2013, it placed at number 355 on NME's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.[82]

Track listing[edit]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Personality Crisis" | David Johansen, Johnny Thunders | 3:41 |

| 2. | "Looking for a Kiss" | Johansen | 3:19 |

| 3. | "Vietnamese Baby" | Johansen | 3:38 |

| 4. | "Lonely Planet Boy" | Johansen | 4:09 |

| 5. | "Frankenstein (Orig.)" | Johansen, Sylvain Sylvain | 6:00 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Trash" | Johansen, Sylvain | 3:08 |

| 2. | "Bad Girl" | Johansen, Thunders | 3:04 |

| 3. | "Subway Train" | Johansen, Thunders | 4:21 |

| 4. | "Pills" | Bo Diddley | 2:48 |

| 5. | "Private World" | Johansen, Arthur Kane | 3:39 |

| 6. | "Jet Boy" | Johansen, Thunders | 4:41 |

Personnel[edit]

Credits are adapted from the album's liner notes.[83]

New York Dolls

- David Johansen – gong, harmonica, vocals

- Arthur "Killer" Kane – bass guitar

- Jerry Nolan – drums

- Sylvain Sylvain – piano, rhythm guitar, vocals

- Johnny Thunders – lead guitar, vocals

Additional personnel

- Buddy Bowser – saxophone

- Jack Douglas – engineering

- David Krebs – executive production

- Steve Leber – executive production

- Paul Nelson – executive production

- Dave O'Grady – makeup

- Todd Rundgren – additional piano, Moog synthesizer, production

- Ed Sprigg – engineer

- Alex Spyropoulos – piano

- Marty Thau – executive production

- Toshi – photography

Release history[edit]

Information is adapted from Nina Antonia's Too Much Too Soon: The New York Dolls (2006).[84]

| Year | Region | Format | Catalog | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | France | LP | 6 398 004 | |||

| Japan | RJ-5 103 | |||||

| Netherlands | 6 336 280 | |||||

| Spain | 6338270 | |||||

| United Kingdom | 6 338 270 | |||||

| United States | 8-track tape | MC-8-1-675 | ||||

| cassette | MCR-4-1-675 | |||||

| LP | SRM-1-675 | |||||

| 1977 | United Kingdom | double LP* | 6641631 | |||

| 1986 | cassette* | PRIDC 12 | ||||

| double LP* | PRID 12 | |||||

| 1987 | Japan | CD* | 33PD-422 | |||

| United States | CD | 832 752-2 | ||||

| 1989 | Japan | 23PD110 | ||||

| 1991 | PHCR-6043 | |||||

| (*) packaged with Too Much Too Soon. | ||||||

See also[edit]

- Lipstick Killers – The Mercer Street Sessions 1972

- List of rock albums

- Timeline of punk rock

- Todd Rundgren discography

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Erlewine (a) n.d.

- ^ Myers 2010, p. 83.

- ^ Blush 2016, p. 102.

- ^ a b c d Myers 2010, p. 84.

- ^ Erlewine (a) n.d.; Antonia 2006, p. 55.

- ^ a b c d e Myers 2010, p. 85.

- ^ Erlewine (a) n.d.; Hermes 2012, p. 18

- ^ Myers 2010, pp. 73, 79, 84–6.

- ^ Erlewine (a) n.d.; Myers 2010, pp. 84–5

- ^ Myers 2010, pp. 84–5.

- ^ Gimarc 2005, p. 7; Myers 2010, p. 86

- ^ a b c Myers 2010, p. 86.

- ^ Fletcher 2009, p. 318.

- ^ Myers 2010, p. 86; Anon. 2007c, p. 316

- ^ Antonia 2006, pp. 123, 134.

- ^ Gerstenzang 2013; Myers 2010, p. 85.

- ^ Gerstenzang 2013.

- ^ a b c Anon. 2007c, p. 316.

- ^ a b c d e f Myers 2010, p. 87.

- ^ a b c d Myers 2010, p. 88.

- ^ a b c d e f Myers 2010, p. 89.

- ^ a b c Gimarc 2005, p. 7.

- ^ Reynolds 2011, p. 245; Antonia 2006, p. 46

- ^ Antonia 2006, p. 55.

- ^ a b c Erlewine (b) n.d.

- ^ Christgau 1998, p. 195; Matsumoto 1994

- ^ a b Hilburn 1987.

- ^ a b Christgau 1981, p. 279.

- ^ Antonia 2006, pp. 81–2.

- ^ Christgau 1998, p. 194; Glover 1973

- ^ Kogan 2006, p. 114.

- ^ Graff 1996, p. 811.

- ^ Christgau 1998, pp. 197–8.

- ^ a b Christgau 1998, p. 198.

- ^ Taylor 2006, p. 163.

- ^ Christgau 1998, p. 197.

- ^ Kogan 2006, p. 116.

- ^ Antonia 2006, "Chapter 6: Little L.A. Women"; Gimarc 2005, p. 7.

- ^ Gimarc 2005, p. 8.

- ^ Myers 2010, p. 90; Smith 2009, p. 106

- ^ Strong 2002, p. 126.

- ^ Erlewine (a) n.d.; Strongman 2008, p. 44

- ^ Fletcher 2009, p. 319.

- ^ Anon. 2003a.

- ^ Strongman 2008, p. 44.

- ^ Strongman 2008, p. 45.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 106.

- ^ Pilchak 2005, p. 105.

- ^ Pilchak 2005, p. 106.

- ^ Pilchak 2005, p. 106; Pilchak 2005, pp. 105–6

- ^ Strongman 2008, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Fletcher 2009, p. 823.

- ^ Antonia 2006, p. 77.

- ^ a b c Myers 2010, p. 90.

- ^ Willis 1973, p. 234.

- ^ Christgau 1973.

- ^ Glover 1973.

- ^ Christgau 1990, p. 106.

- ^ Cagle 2013, p. 136.

- ^ Fletcher 2009, p. 319; Erlewine (a) n.d.; Anon. 2007c, p. 316.

- ^ Eddy 1997, p. 330.

- ^ Fletcher 2009, p. 319; Smith 2009, p. 106

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 104–5.

- ^ Anon. 2007a.

- ^ Robb 2010; Myers 2010, p. 83.

- ^ McLeese 1987, p. 52.

- ^ Larkin 2006, p. 176.

- ^ Wicks 1996.

- ^ Anon. 2002, p. 139.

- ^ a b Fricke 2000, p. 74.

- ^ Gross 2004, p. 583.

- ^ Weisbard & Marks 1995, p. 269.

- ^ Anon. 2007c, p. 316; Larkin 2006, p. 176.

- ^ Gross 2004, p. 584.

- ^ Cooper 1982, p. 148.

- ^ Christgau 1979; Christgau 2005; Christgau 2000.

- ^ Strauss 1996, pp. 3–8; Weisbard & Marks 1995, appendix.

- ^ Anon. 2002, p. 139; Anon. 2003b, p. 76; Anon. 1995, pp. 50–89

- ^ Anon. 2003a; Anon. 2004.

- ^ Anon. 2012; Anon. 2020.

- ^ Anon. 2007b.

- ^ Kaye 2013.

- ^ Anon. 1973.

- ^ Antonia 2006, pp. 214–17.

Bibliography[edit]

- Anon. (1973). New York Dolls (liner notes). New York Dolls. Mercury Records. SRM-1-675.

- Anon. (August 1995). "The 100 Greatest Albums Ever Made". Mojo. London.

- Anon. (May 2002). "100 Best Punk Albums". Q. London.

- Anon. (March 2003). "Top 50 Punk Albums". Mojo. London.

- Anon. (November 1, 2003). "213) New York Dolls". Rolling Stone. New York. Archived from the original on September 2, 2006. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- Anon. (December 9, 2004). "Personality Crisis". Rolling Stone. New York. Archived from the original on July 2, 2006. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- Anon. (November 21, 2007). "Artists beginning with N". The Guardian. 1000 albums to hear before you die. London. Archived from the original on November 25, 2013. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- Anon. (July 3, 2007). "BMI Songwriters Dominate Mojo's '100 Records That Changed The World'". Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI). Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- Anon. (2007). "New York Dolls". In Irvin, Jim; McLear, Colin (eds.). The Mojo Collection (4th ed.). Canongate Books. ISBN 978-1-84767-643-6.

- Anon. (May 31, 2012). "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- Anon. (September 22, 2020). "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- Antonia, Nina (2006). Too Much Too Soon: The New York Dolls (3rd ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 1-84449-984-7.

- Blush, Steven (2016). New York Rock: From the Rise of The Velvet Underground to the Fall of CBGB. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1250083616.

- Cagle, Van M. (2013). "Trudging Through the Glitter Trenches". In Waldrep, Shelton (ed.). The Seventies: The Age of Glitter in Popular Culture. Routledge. ISBN 978-1136690617.

- Christgau, Robert (1973). "New York Dolls Manuscript". Newsday. Melville. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- Christgau, Robert (December 17, 1979). "Decade Personal Best: '70s". The Village Voice. New York. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- Christgau, Robert (1981). "Consumer Guide '70s: N". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 0-89919-025-1. Retrieved March 8, 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- Christgau, Robert (1990). Christgau's Record Guide: The '80s. Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-679-73015-X.

- Christgau, Robert (1998). Grown Up All Wrong: 75 Great Rock and Pop Artists from Vaudeville to Techno. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-44318-7.

- Christgau, Robert (2000). "How to Use These Appendices". Christgau's Consumer Guide: Albums of the '90s. Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-24560-2. Retrieved February 24, 2021 – via robertchristgau.com.

- Christgau, Robert (October 2005). "New York Dolls: 'Too Much Too Soon'". Blender. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- Cooper, B. Lee (1982). Images of American Society in Popular Music: A Guide to Reflective Teaching. Taylor Trade Publications. ISBN 0-88229-514-4.

- Eddy, Chuck (1997). The Accidental Evolution of Rock'n'roll: A Misguided Tour Through Popular Music. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306807416.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (a) (n.d.). "New York Dolls : Biography". AllMusic. All Media Network. Archived from the original on September 10, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (b) (n.d.). "New York Dolls – New York Dolls". AllMusic. All Media Network. Archived from the original on March 26, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- Fletcher, Tony (2009). All Hopped Up and Ready to Go: Music from the Streets of New York 1927–77. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-33483-8.

- Fricke, David (April 27, 2000). "New York Dolls". Rolling Stone. New York.

- Gerstenzang, Peter (July 24, 2013). "Why Aren't the New York Dolls in the Rock Hall of Fame?". Esquire. New York. Archived from the original on April 17, 2016. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- Gimarc, George (2005). Punk Diary: The Ultimate Trainspotter's Guide To Underground Rock, 1970–1982. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 0-87930-848-6.

- Glover, Tony (September 13, 1973). "New York Dolls". Rolling Stone. New York. Archived from the original on April 14, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- Graff, Gary (1996). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Visible Ink Press. ISBN 0-7876-1037-2.

- Gross, Joe (2004). "New York Dolls". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Hermes, Will (2012). Love Goes to Buildings on Fire: Five Years in New York That Changed Music Forever. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-374-53354-0.

- Hilburn, Robert (November 17, 1987). "Compact Discs". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- Kaye, Ben (2013). "The Top 500 Albums of All Time, According to NME". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on August 15, 2015. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- Larkin, Colin (2006). Encyclopedia of Popular Music (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195313739.

- Kogan, Frank (2006). Real Punks Don't Wear Black: Music Writing. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0820327549.

- Matsumoto, Jon (September 29, 1994). "The New York Dolls". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- McLeese, Don (November 4, 1987). "Reissue of Dolls' debut is stiletto-sharp". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 3, 2014. (subscription required)

- Myers, Paul (2010). A Wizard, A True Star: Todd Rundgren in the Studio. Jawbone Press. ISBN 978-1-906002-33-6.

- Pilchak, Angela (2005). Contemporary Musicians: Profiles of the People in Music. Vol. 51. Gale. ISBN 1-4144-0554-5.

- Reynolds, Simon (2011). Retromania: Pop Culture's Addiction to Its Own Past. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-86547-994-4.

- Robb, John (2010). "Morrissey Reveals His Favourite LPs Of All Time". The Quietus. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- Smith, Chris (2009). 101 Albums That Changed Popular Music. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537371-4.

- Strauss, Neil (1996). "The 100 Most Influential Alternative Releases of All Time". In Schinder, Scott (ed.). Rolling Stone's Alt Rock-a-rama. Delta. ISBN 0385313608.

- Strong, Martin Charles (2002). The Great Rock Discography. The National Academies. ISBN 1-84195-312-1.

- Strongman, Phil (2008). Pretty Vacant: A History of UK Punk. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-752-4.

- Taylor, Steve (2006). The A to X of Alternative Music. Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-8217-1.

- Weisbard, Eric; Marks, Craig, eds. (1995). Spin Alternative Record Guide. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-75574-8.

- Wicks, Todd (1996). "New York Dolls". In Graff, Gary (ed.). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Visible Ink Press. ISBN 0787610372.

- Willis, Ellen (November 19, 1973). "Frankenstein at the Waldorf". The New Yorker.

Further reading[edit]

- Alexander, Phil (July 31, 2013). "New York Dolls: Jet Boy At 40". Mojo. London.

- Buskin, Richard (December 2009). "New York Dolls 'Personality Crisis'". Sound on Sound. Cambridge.

- Christgau, Robert (December 21, 1972). "Classy Dolls at the Mercer". Newsday. Melville.

- Christgau, Robert (February 1973). "In Love With the New York Dolls". Newsday. Melville.

- Mendelsohn, Jason; Klinger, Eric (August 23, 2013). "Counterbalance No. 138: 'New York Dolls'". PopMatters.

- Olliver, Alex (September 20, 2017). "The New York punk albums you need in your record collection". Louder.

- Phillips, Binky (September 25, 2013). "July 27, 1973: The 40th Anniversary of the Release of the Debut Album by The New York Dolls... Their Fan Club President Remembers". The Huffington Post.

External links[edit]

- New York Dolls at Discogs (list of releases)