Nam tiến

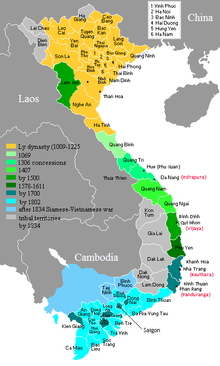

Nam tiến (Vietnamese: [nam tǐən]; chữ Hán: 南進; lit. "southward advance" or "march to the south") is a historiographical concept[a][2] that describes the historic southward expansion of the territory of Vietnamese dynasties' dominions and ethnic Kinh people from the 11th to the 19th centuries.[3][4][5] The concept of Nam tiến has differing interpretations, with some equating it to Viet colonialism of the south and to a series of wars and conflicts between several Vietnamese dynasties[b] and Champa Kingdoms, which resulted in the annexation and Vietnamization of the former Cham states as well as indigenous territories.[c] The nam tiến became one of the dominant themes of the narrative that Vietnamese nationalists created in the 20th century, alongside an emphasis on non-Chinese origin and Vietnamese homogeneity.[6]: 7 Within Vietnamese nationalism and Greater Vietnam ideology, it served as a romanticized conceptualization of the Vietnamese identity, especially in South Vietnam and modern Vietnam.[7]

The Viet domain was gradually expanded from its original heartland in the Red River Delta into southern territories, which were controlled by the Champa kingdoms. In a span of some 700 years, the Viet domain tripled the area of its territory and more or less acquired the elongated shape of modern-day Vietnam.[8] Beginning in the 20th century, modern Vietnamese historiography, under the auspices of nationalism and racialism,[9][10] coined the term Nam tiến for what they believed to be a gradual, inevitable southern expansion of Vietnamese domains. According to the 20th-century Vietnamese scholars who constructed the Nam tiến as a continuous historical phenomenon, the 11th to the 14th centuries saw battle gains and losses as frontier territory changed hands between the Viet and the Chams during the early Cham–Viet wars. In the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries, following the Fourth Chinese domination of Vietnam (1407–1427), the Vietnamese defeated the less centralized state of Champa and seized its capital in the 1471 Cham–Vietnamese War. From the 17th to the 19th centuries, Vietnamese settlers penetrated the Mekong Delta. The Nguyễn lords of Huế wrested the southernmost territory from Cambodia by diplomacy and by force, which completed the "March to the South".

History

[edit]11th to 14th centuries (Lý and Trần dynasties)

[edit]Records suggest that there was an attack on the Champa kingdom and its capital, Vijaya, from Vietnam in 1069 (under the reign of Lý Thánh Tông) to punish Champa for armed raids in Vietnam. Cham King Rudravarman III was defeated and captured. He offered Champa's three northern provinces to Vietnam (now Quảng Bình and northern partQuảng Trị Provinces).[11]: 62, 186 [12]

In 1377, the Cham capital was unsuccessfully besieged by a Vietnamese army during the Battle of Vijaya.[13]

15th to 19th centuries (Later Lê dynasty to the Nguyễn lords)

[edit]The native inhabitants of the Central Highlands are the Degar (Montagnard) people but otherwise are mostly Katuic, Bahnaric, and Chamic-speaking peoples. The Vietnamese from the Dai Viet conquered and annexed the area during their southward expansion.

Major Champa–Vietnam Wars were fought again in the 15th century during the Lê dynasty, which eventually led to the defeat of Vijaya and to the demise of Champa in 1471.[14] The citadel of Vijaya was besieged for one month in 1403 until the Vietnamese troops had to withdraw because of a shortage of food.[14] The final attack came in early 1471, after almost 70 years without a major military confrontation between Champa and Vietnam. It is interpreted to have been a reaction to Champa asking Chinese Ming dynasty for reinforcements to attack Vietnam.[15]

Cham provinces were seized by the Vietnamese Nguyễn lords.[16] Provinces and districts that had been originally controlled by Cambodia were taken by Vo Vuong.[17][18]

Cambodia was constantly invaded by the Nguyễn lords. Around a thousand Vietnamese settlers were slaughtered in 1667 in Cambodia by a combined Chinese-Cambodian force. Vietnamese settlers started to inhabit the Mekong Delta, which was previously inhabited by the Khmer. That caused the Vietnamese to be subjected to Cambodian retaliation.[19] The Cambodians told Catholic European envoys that the Vietnamese persecution of Catholics justified retaliatory attacks to be launched against the Vietnamese colonists.[20]

19th century (Nguyễn dynasty)

[edit]

Vietnamese Emperor Minh Mang enacted the final conquest of the Champa Kingdom by a series of Cham–Vietnamese Wars. In 1832, the Emperor annexed Champa while the Vietnamese coercively fed lizard and pig meat to Cham Muslims and cow meat to Cham Hindus, against their will, to punish them and to assimilate them to Vietnamese culture.[21] The Cham Muslim leader Katip Suma, who was educated in Kelantan, came back to Champa and led the dissatisfied Champa Muslims to declare a jihad revolt against Vietnamese rulers, but he was promptly defeated.[22][23][24][25]

Minh Mang sinicized ethnic minorities such as Cambodians, claimed the legacy of Confucianism and China's Han dynasty for Vietnam, and used the term Han people 漢人 (Hán nhân) to refer to the Vietnamese.[26] Minh Mang declared, "We must hope that their barbarian habits will be subconsciously dissipated, and that they will daily become more infected by Han [Sino-Vietnamese] customs."[27] The policies were directed at the Khmer and the hill tribes.[28] The Nguyen lord Nguyen Phuc Chu had referred to Vietnamese as "Han people" in 1712 to differentiate them from Chams.[29] The Nguyễn lords established đồn điền, state-owned agribusiness, after 1790. Emperor Gia Long (Nguyễn Phúc Ánh), in differentiating between Khmer and Vietnamese, said, "Hán di hữu hạn [ 漢|夷|有限 ]" meaning "the Vietnamese and the barbarians must have clear borders."[30] His successor, Minh Mang, implemented an acculturation integration policy directed at minority non-Vietnamese peoples.[31] Phrases like Thanh nhân (清人, Qing people) or Đường nhân (唐人, Tang people) were used to refer to ethnic Chinese by the Vietnamese, who called themselves as Hán dân (漢民) and Hán nhân (漢人) in Vietnam in the 1800s, under the Nguyễn dynasty.[32]

Historicity

[edit]Analysis and periodization

[edit]Michael Vickery articulates that Nam tiến was not steady, and its stages show that there was no continuing policy of southward expansion. Each territorial push was a move or reaction against a particular historical event. A famous historian of pre-colonial Vietnam, Keith W. Taylor, totally opposes and rejects the idea of Nam tiến, as he provides alternate explanations.[33] Momorki Shirō, a historian from Osaka University, has criticized the Nam tiến as a "Kinh-centric historical view." Rather than an authentic continuous historical phenomenon, it is a colonial and postcolonial nationalist historiographic construction.[34]

Scholarly consensus does agree that Vietnamese southward expansions that have been conceptualized into the modern-day Nam Tiến did not start until at least the early 15th century AD. Numerous wars were fought between Champa and Đại Việt before the 1400s, but they happened indecisively, and there were territorial exchanges on both sides. Some scholars put the starting date of Nam Tiến to 1471, precisely when the word Nam tiến itself began to be used. Therefore, the starting date of the 11th century should be rejected.[35]

Nam Tiến in South Vietnam/Republic of Vietnam (RVN)

[edit]At the onset of the 20th century, nationalism swept across the globe. In Asia, nationalists and advocates of the nation-state must have been joyful in crafting homogenous nationalities like "Chinese," "Cambodian," "Vietnamese," etc., which in common assumptions are as almost synonymous with the predominant ethnic group. The Nam tiến emerged at that time. In the postcolonial Republic of Vietnam, Vietnamese (Kinh) intellectuals began the selective remembering of history to construct sources of national pride for the newly formed Vietnamese nation. They probably found or inherited the idea from Hung Giang's article La Formation du pays d’Annam, published in July 1928. In that first nationalist narrative praising the Nam tiến, Lord Nguyễn Hoàng allegedly "urged his people to keep moving southward," coined as Nam tiến.[34]

Early French scholarships in the late 19th century shaped Indianized kingdoms like Angkor and Champa, which had been declined mainly from Vietnamese expansionism, and mimicked them as the main villains who emerged at the end of the tale. Thereby, the French hypedly acted as "rescuers" of "lost civilizations" and prevent their heritage from being completely "swallowed up" by the Vietnamese by colonization and assimilation. After 1954, scholars in North and South Vietnam held varying reactions to French Cham studies. One side from Hanoi promoted the "multi-ethnic history" and "solidarity between peoples against invaders and feudal rulers" to fit its Marxist historiography and so little attention was paid to Champa itself. The other side celebrated the ethnohistory, virtually at odds with the Hanoi historiography. Frankly, Vietnamese nationalist writers in post-colonial Vietnam who were mesmerized by the French hyped interpretation of the Vietnamese conquest of Champa, began using it as evidence for "ancient Vietnamese greatness."[36]

The most famous apostle of the Nam tiến in RVN in Saigon, Việt sử: Xứ Đàng Trong 1558–1777: Cuộc Nam tiến của dân tộc Việt Nam, an essay of Vietnamese Nam Tiến ‘Southward March’, by the historian Phan Khoang (1906–1971), synthesizing a 'very real' concept of Nam tiến at its title, also the most detailed book about the Nam Tiến.[37] In the book, the author offers a quite strong Vietnamese-centric biased view and stereotyping negative sentiments toward the "conquered people." The book's main discourse is about the presumed "march" (piecing unrelated and distant events together) of the Vietnamese along the coast from the Red River Delta, traditionally said to be begun in the 11th century, until they reached the end tail of the Mekong Delta in 18th century.[1] The essay concerning Champa begins by treating it as a single unified kingdom, like framework of early French scholars, and tracing the kingdom's genesis to the Indianized Linyi (Lâm Ấp). Little attention was paid to the civilizational aspects of the Cham, Khmer, and indigenous groups. They were considered by earlier colonial-era works indiscriminately as the same "Indianized origins."[1] Those colonial scholars had introduced blatant Eurocentric-framed concepts like 'Sinic or Indic civilization spheres,' denying and downplaying the achievements of indigenous non-nation peoples of Southeast Asia. Ironically, they are still widely in practice today.[38]

During early colonial Indochina, French ethnographers used the Vietnamese collective pejorative for indigenous peoples of the Central Highlands, Mois,[36] a word carrying extremely negative connotations, imposed it on the peoples, and embraced both European and Viet colonialism in the Highlands.

Phan Khoang discusses in his essay wars between Champa and Đại Việt caused by assured "Cham aggression" by claiming that "the inferiority and aggressiveness of the Cham were the ultimate reasons leading to their fall." He convinces that the Cham were "a weaker nation" had to give ground for "the stronger nation" of the Vietnamese.[39] Furthermore, Phan explains the demise of the final Cham kingdom in 1832 had originated from the Tây Sơn rebellion and shows little pity for the fate of the Cham people in the aftermath. Nevertheless, in the end, Phan Khoang highlights "the fierce and vitality of the Vietnamese nation" that wiped out Champa and gave a grateful sense of nationalistic pride. However, he notes that those events should be left open, rather than defended, defamed, or covered.[40]

One popular author of Nam Tiến exponent in the RVN was Phạm Văn Sơn (1915–1978). In the Nam tiến section of the 1959 edition of his national history Việt sử tân biên, Phạm Văn Sơn pushed triumphalist Darwinist nuances for Nam Tiến.[40] Arguing that the Cham had mounted numerous border incursions against the "homogeneousic Vietnamese Jiaozhi and Annan" ruled by Chinese dynasties before the 10th century, he attempted to justify Vietnamese invasions of Champa in that century as retribution. As 'Vietnam' "gained independence from China," it began to move southward constantly and unstoppable because the Cham, Khmer, and indigenous peoples, according to him, were "lacking capacity and advancement to develop, and remained primitive."[40]

Another popular book on Nam Tien in the RVN was Dohamide and Dorohime's Dân tộc Chàm lược sử (1965), the first modern history of the Cham people.[41] The brother-historians of Cham Sunni background constructed the Nam tiến as a "process of invasion and occupation on the part of the Vietnamese." They postulated that from the 11th century onward, "Cham history was henceforth merely the retreat of 'Indian' civilization in the face of 'Chinese' civilization." They consider the conflict between Champa and Dai Viet to be due to Champa's "need to expand to the North, which was much more fertile."[42]

The core idea of Nam tiến is the superiority of the Vietnamese (Kinh) people, culturally and racially, over the "conquered people" (Khmer, Cham, and other Austroasiatic, Austronesian, Kra-Dai, and Hmong-Mien speaking peoples). In such a popular narrative, "the fertile productive fields and wealth of the South had been brought by the civilizing force of the Viet people upon the uncivilized" is comparable with the "Vietnamese man's burdens." Non-Vietnamese peoples are depicted as backward and alien, as opposed to the cultured, perfect, innovative Viet society. Thus, since non-Viet groups have been portrayed as stagnant backward and unable to resist, and the Viet were demonstrated as superior, the Nam Tiến is thought of as a steady and irreversible "marching" process. RVN intellectuals quite publicly acknowledged the unpleasant history of the nation's past and allowed reversals to be published freely and expressed. Overall, Vietnamese victories and the conquest of the South were proudly appreciated by the RVN intellectuals.[43]

Nam Tiến in North Vietnam/Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) and Post-1975 Vietnam/Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV)

[edit]In the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), perceptions of Nam Tiến were at first unsympathetic. In the three-volume Lịch sử chế độ phong kiến Việt Nam (LSCĐPK, History of the Feudal System of Vietnam), published in 1959–1960, DRV historians likely employed Marxist and Confucian doctrines and Vietnamese subjectivism to judge past between Champa and Đại Việt.[44] The wars of 980, the 1380s, the 1430s, and the 1440s were labeled as "self-defense" and "righteous" (chính nghĩa), and wars that brought territorial acquisitions to Đại Việt were called "aggression" (xâm lược) or "invasions" (xâm lăng), otherwise "wrongful" one (phi nghĩa).[44] The book condemns all Vietnamese rulers after 1471. The Nam Tiến is remembered as a colonization process involving "murderous warfare and land-grabbing by the Nguyễn feudalists targeting two weakened neighbors." It paradoxically admitted that the Cham people had eventually become a part of the "Great Vietnamese nation" and that "Cham history deserves to be taught."[45]

After the fall of Saigon, most Nam Tiến writers went overseas. Within the new Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), communist authors produced a revised version of history according to their views that suppresses the discourse of Nam Tiến. Reasons behind the suppression of Nam Tiến after 1975 were not because its racist negativism and ethnonationalism, but its contradiction of the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP) agenda.[46] Since the 20th century, as Vietnam was put on the thermotic ideological frontline of the Cold War between the world superpowers, Vietnamese nationalists and Marxists usually bolstered the perception about the Vietnamese as the oppressed people under the tyranny of foreign powers, "China",[d] French colonialism and American imperialism, not the antithetical position that the Vietnamese also have been spiteful colonizers and victimizers themselves.[46][50] Consequently, the history version portrays the image of an oppressed but proudly, stubborn, determined Vietnamese nation who thrashed off the yokes of foreign imperialism, has been becoming the rallying point of Vietnamese nationalism, goes completely conflicted with the inconsistent reality of Vietnamese colonialism presented in the Nam Tiến.[51][52]

Studying or remembering Viet colonialism and nationalism against marginalized and indigenous peoples eventually damaged the Vietnamese Revolution and the party's reputation with leftist thinkers outside Vietnam. Furthermore, it provoked indigenous nationalism against the party and Vietnam. Building the impression of ethnic and religious harmony under socialism was also important.

The Nam tiến theory and the former South Vietnamese intellectual works were targets of Vietnamese Marxist critique and suppression for the sake of peace and the protection of good reputations. Criticism against the predominant Kinh also mitigated. Unlike the 1959 LSCĐPK, the Vietnamese and the assumed homogenous Vietnam were gradually recast and corrected as the ultimate victims, not the victimizers. Therefore, post-1960 Hanoi authors' writings saw significant shifts. Especially the 1971 DRV official history Lịch Sử Việt Nam, the Viet conquest of the South was misinterpreted into just simply groundless semi-pseudohistory 'migration of Viet people,' exclusively claimed that the migrants peacefully coexisted with the original inhabitants or settled on wildlands that had long been magically abandoned or uninhabited,[53][54][55] without even an indistinct mention about the reality of wars and the resistance of the Cham and the indigenous peoples.[45][52] Ethnic tensions between the Vietnamese with the Cham and the Khmer peoples and the suffering of conquered people become mere disputes between "feudal" rulers.[56] For a while, it has been the mainstream thesis of Vietnam's "territorial evolution." After that 1971 publication, Champa and non-Kinh cultures were disenfranchised by being pulled out of the historiography and barely mentioned very briefly as merely insignificant outsiders.[45]

In recent works in the context of Đổi Mới, SRV authors have reinserted several ideas of the Nam tiến to depict Champa, such as "aggressiveness" and "Cham provocations" while tending to portray Vietnamese southern advance as progressive.[57][58] The Nguyễn, the last Vietnamese dynasty, which had long been slammed by Marxist scholars, are seemingly rehabilitated in the Vietnamese historiography.[59] The recent reappearance of the Nam tiến in Vietnamese academic works is considered highly significant.[59] It suggests that state historians are no longer sensitively dictating RVN intellectual writings and those from international scholarship, or it may be from SRV historians' reaction to geopolitical change, particularly by growing irredentist sentiments in neighboring Cambodia.[60]

Reception

[edit]The nam tiến has been described by historians Nhung Tuyet Tran and Anthony Reid as one of the dominant themes of the narrative that Vietnamese nationalists created in the 20th century, alongside an emphasis on non-Chinese origin and Vietnamese homogeneity.[6]: 7

Vietcentric Nam tiến thinking has had a great impact on Vietnam. Although SRV scholars have done a great amount of research on non-Viet cultures, they are not willing to analogize those cultures with the formation of Vietnam or to recognize the multicultural origins of the country.[61] National museums in Vietnam contain no mention of non-Kinh cultures such as the Cham, Khmer, or Austronesians in the timeline of the making of Vietnam.[62] Kinh history is said to have begun with profound[clarification needed] Văn Lang kingdoms under the Hùng kings, which are often identified with the Dong Son culture, are exhibited and occupy almost the entire disproportionate chronology. Overall, the Kinh are indisputable protagonists in the history of Vietnam, whereas the role of other ethnic groups is downplayed.[63] Non-Kinh "ethnic minority" artifacts are displayed as aesthetic objects in separated rooms, not about history and heritage, with little care, likely tourism magnets.[64] They are intentionally placed in peripheral, outsider roles, and are not included in Vietnamese mainstream historiography although they made enormous contributions or had a direct historical impact on Vietnam and Southeast Asia as a whole.[65][62] Claire Sutherland, a lecturer at Northumbria University, summarizes the way in which Vietnamese nationalism constructs an illusion of Vietnam's homogeneity as follows: "Official histories characterised Vietnam as a single, fixed bloc, with a common language, territory, economy and culture."[66] Sutherland notes regarding Vietnamese museums, "Non-Kinh cultures, both ancient and modern, are given a peripheral role, but are not deemed to form a part of the core, nation-building narrative. Creating an impression of Vietnam as a monolithic bloc is thus preferred to charting its gradual territorial expansion, with all the different regional histories that this would entail."[62] Modern Vietnamese nationalism insists on the maintenance of Vietnam's homogeneous notion by inventing and persisting the "core ethnic group" hegemony in the formation of the country, while other cultures like the Cham are marginalized or excluded. The "Vietnam" seen through mainstream representations is extremely generalized with broadly political buzzwords and rhetorical constructs, which lead to fallacies. It also ignores the fact that Vietnam as well as the whole of Southeast Asia are among the most ethnolinguistically diverse places on Earth.[citation needed]

Historian C. Goscha argues that the north-south Nam tiến narrative is very ethnocentric. It downplays the importance of non-Kinh peoples, who constituted the majority of Vietnam's population until the late 20th century. Indigenous peoples had inhabited large areas of Vietnam independently for thousands of years before the Vietnamese government described them as ethnic minorities in the 20th century.[67] They have their own history and stories, interactions with the Vietnamese, and perspectives, which should not be neglected. Both contributed to each other a lot in making up Vietnam as well as part of the global culture. Indeed, "until recently there was no single S-like Vietnam running from north to south."[46] Goscha argues that balancing between Vietnamese centrality and non-Vietnamese centrality is important, and something-centrism[clarification needed] should be avoided.[68]

Legacy

[edit]French colonial rule to late 20th century

[edit]During the French colonial era, ethnic strife between Cambodia and Vietnam was somewhat pacified as both were parts of French Indochina. However, intergroup relations deteriorated even further, as the Cambodians viewed the Vietnamese as being a privileged group, who were allowed to migrate into Cambodia. All postcolonial Cambodian regimes, including the governments of Lon Nol and of the Khmer Rouge, relied on anti-Vietnamese rhetoric to win popular support.[69]

In South Vietnam, intellectuals treated and consolidated the Nam tiến as an established factual history, obviously with approaches for nationalistic purposes. They saw the Nam tiến and its consequences as matters of national pride and explained a Vietnamese-dominated Vietnam with racial and cultural nationalistic viewpoints.[37] After 1975, Hanoi scholars, on the other hand, emphasized the multiethnic solidarity and peaceful interrelating coexistence of Viet-Cham, Viet-Khmer, and non-Viet and so favored a reconstruction of a multi-ethnic history but tended to skip the discourse on Vietnamization of Champa and other indigenous peoples otherwise. They also limited the use of Nam tiến.[70]

After 1975, some French academics sought to revive the importance of Champa itself as a historical independent polity and non-Vietnamese indigenous history that deserves to have its own rights and tractions in the history of Vietnam, rather than being scraped aside, becoming peripherical in the Vietnamese version of history, and therefore clashing with Viet-centric historiography. After the đổi mới, the narrative of Nam tiến has seen a renewal in Vietnam and has been popularised in recent years.[59]

Nowadays

[edit]Nowadays it is widely acknowledged that the Vietnamese were originally natives of north Vietnam and south China, who then expanded southwards, and that lands to the south are native lands of Chams and Khmers.[citation needed] Many Cambodians, including politician Sam Rainsy, hold the irredentist belief that the Cambodian lands currently belonging to Vietnam should be returned to Cambodia.[71]

Whilst relations between Chams, Khmers and Vietnamese are cordial and respectful, with a long and complicated history with each other,[citation needed] relations with the government centralised in Hanoi are still sensitive.[72] Human Rights Watch has criticised the government of Vietnam for its rights abuses of the ethnic Khmer in Mekong Delta, such as the imprisonment or house arrest of Khmer Krom Buddhist monks peacefully expressing their religious or political views, restrictions on Khmer-language publications, banning and confiscation of Khmer Krom human rights advocacy materials, harassment or arrest of people disseminating such materials, as well as harassment, intimidation, and imposition of criminal penalties on individuals of Khmer Krom human rights advocacy groups in contact with international organizations.[73]

Genetic analysis

[edit]Nam Tiến is considered by some as the definitive event in which Vietnam became a firmly Southeast Asian nation upon annexing territories formerly belonging to the Champa and part of Cambodia. All Vietnamese carry Southeast Asian haplotypes. The dramatic population decrease experienced by the Cham 700 years ago fits well with the southwards expansion from the Vietnamese original heartland in the Red River Delta. Autosomal SNPs consistently point to important historical gene flow within mainland Southeast Asia, and add support to a major admixture event occurring between "Chinese" and a southern Asian ancestral composite (mainly represented by the Malay). This admixture event occurred approximately eight centuries ago, again coinciding with the Nam tiến.[74]

See also

[edit]- History of the Cham–Vietnamese wars

- Champa

- Chey Chettha II

- Khmer Empire

- Tonkin and Cochinchina

- Cambodian–Vietnamese War of the 1970s and 1980s

- Ostsiedlung

- Chuang Guandong

Notes

[edit]- ^ The concept was first formulated during the 20th century, then in both North (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam).[1]

- ^ Particularly the Dai Viet Kingdom during the Le dynasty (1428–1788) and the succeeding Nguyen kingdom (1558–1945)

- ^ Scholar Anne-Valérie Schweyer doubts that Nam tiến constitutes a historical process. She describes the term as "an ideological creation of the end of the 20th century", which therefore makes no sense in the polyethnic spaces of ancient and modern times.

- ^ The Reinventions of China and Vietnam by 20th century nationalism traditionally assume the myth that there are unbreakable continuities of "nation-states" of China and Vietnam that have been lasting for "thousands of years" and they are "long-time enemies," "country version of David and Goliath."[47][48] However, this concept is complicated by early 21st century economic history where China remains the biggest trader of Vietnam and the largest trading nation in 2013. Nevertheless, a David and Goliath perception between Vietnam and China remains.[49]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Lockhart 2011, p. 11.

- ^ Reid, Anthony (2015). A History of Southeast Asia: Critical Crossroads. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-11851-300-2.

- ^ Nguyen, Duy Lap (2019). The unimagined community: Imperialism and culture in South Vietnam. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-1-52614-398-3.

- ^ Anne-Valérie Schweyer (2019). "The Chams in Vietnam: a great unknown civilization". French Academic Network of Asian Studies. Archived from the original on July 2, 2022. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ Rahman, Smita A.; Gordy, Katherine A.; Deylami, Shirin S. (2022). Globalizing Political Theory. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9781000788884.

- ^ a b Tran, Nhung Tuyet; Reid, Anthony, eds. (2006). Viet Nam: Borderless Histories. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299217730.

- ^ Pelley, Patricia M. (2002). Postcolonial Vietnam: New Histories of the National Past. Duke University Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-822-32966-4.

- ^ Nguyen The Anh, "Le Nam tien dans les textes Vietnamiens", in P. B. Lafont, Les frontieres du Vietnam, Harmattan edition, Paris 1989

- ^ Reid, Anthony; Tran, Nhung Tuyet (2006). Viet Nam: Borderless Histories. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-316-44504-4.

- ^ Marr, David G. (2013). Vietnam: State, War, and Revolution (1945–1946). Philip E. Lilienthal book. Vol. 6 of From Indochina to Vietnam: Revolution and War in a Global Perspective (illustrated ed.). University of California Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0520274150. ISSN 2691-0403.

- ^ Maspero, G., 2002, The Champa Kingdom, Bangkok: White Lotus Co., Ltd., ISBN 9747534991

- ^ Nguyen 2009, p. 65.

- ^ Spencer C. Tucker (December 23, 2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 308. ISBN 9781851096725. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- ^ a b Nguyen 2009, p. 68.

- ^ Nguyen 2009, p. 69.

- ^ Elijah Coleman Bridgman; Samuel Wells Willaims (1847). The Chinese Repository. proprietors. pp. 584–.

- ^ George Coedes (May 15, 2015). The Making of South East Asia (RLE Modern East and South East Asia). Taylor & Francis. pp. 175–. ISBN 978-1-317-45094-8.

- ^ G. Coedes; George Cœdès (1966). The Making of South East Asia. University of California Press. pp. 213–. ISBN 978-0-520-05061-7.

- ^ Ben Kiernan (2008). Blood and Soil: Modern Genocide 1500-2000. Melbourne Univ. Publishing. pp. 158–. ISBN 978-0-522-85477-0.

- ^ Ben Kiernan (2008). Blood and Soil: Modern Genocide 1500-2000. Melbourne Univ. Publishing. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-0-522-85477-0.

- ^ Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. pp. 141–. ISBN 978-0-87727-138-3.

- ^ Jean-François Hubert (May 8, 2012). The Art of Champa. Parkstone International. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-1-78042-964-9.

- ^ "The Raja Praong Ritual: A Memory of the Sea in Cham- Malay Relations". Cham Unesco. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- ^ (Extracted from Truong Van Mon, “The Raja Praong Ritual: a Memory of the sea in Cham- Malay Relations”, in Memory And Knowledge Of The Sea In South Asia, Institute of Ocean and Earth Sciences, University of Malaya, Monograph Series 3, pp, 97-111. International Seminar on Maritime Culture and Geopolitics & Workshop on Bajau Laut Music and Dance”, Institute of Ocean and Earth Sciences and the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Malaya, 23-24/2008)

- ^ Dharma, Po. "The Uprisings of Katip Sumat and Ja Thak Wa (1833-1835)". Cham Today. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- ^ Norman G. Owen (2005). The Emergence Of Modern Southeast Asia: A New History. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 115–. ISBN 978-0-8248-2890-5.

- ^ A. Dirk Moses (January 1, 2008). Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History. Berghahn Books. pp. 209–. ISBN 978-1-84545-452-4. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Randall Peerenboom; Carole J. Petersen; Albert H.Y. Chen (September 27, 2006). Human Rights in Asia: A Comparative Legal Study of Twelve Asian Jurisdictions, France and the USA. Routledge. pp. 474–. ISBN 978-1-134-23881-1.

- ^ "Vietnam-Champa Relations and the Malay-Islam Regional Network in the 17th–19th Centuries". kyotoreview.cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp. Archived from the original on June 17, 2004. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-87727-138-3.

- ^ Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. pp. 136–. ISBN 978-0-87727-138-3.

- ^ Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. pp. 137–. ISBN 978-0-87727-138-3.

- ^ Taylor, K. W. (1998). "Surface Orientations in Vietnam: Beyond Histories of Nation and Region". Journal of Asian Studies. 57 (4): 949–978. doi:10.2307/2659300. JSTOR 2659300. S2CID 162579849 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Goscha 2016, p. 512.

- ^ Notes:

- Momorki, Shiro (2011), ""Mandala Campa" Seen from Chinese Sources", in Lockhart, Bruce; Trần, Kỳ Phương (eds.), The Cham of Vietnam: History, Society and Art, Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 120–137, ISBN 978-9-971-69459-3,

Despite the popular view of Đại Việt's steady and irreversible southward expansion (Nam tiến), this process was only realized after the fifteenth century...

- Whitmore, John K. (2011), "The Last Great King of Classical Southeast Asia: Che Bong Nga and Fourteenth Century Champa", in Lockhart, Bruce; Trần, Kỳ Phương (eds.), The Cham of Vietnam: History, Society and Art, Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 168–203,

The myth of a thousand-year Vietnamese Nam Tiến (Southern Push) assumes a constant and continuous movement from the North into Nagara Champa. Instead, we need to see the outer zones of each mandala being contested by both Champa and Đại Việt, at least until the Vietnamese were able to crush Vijaya in 1471..

- Vickery, Michael (2011), "Champa Revised", in Lockhart, Bruce; Trần, Kỳ Phương (eds.), The Cham of Vietnam: History, Society and Art, Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 363–420,

Thereafter the conflicts between the two parties were mostly between equals, and in the last quarter of the fourteenth century (1360–90) the Cham very nearly conquered all of Vietnam. Only after the failure of that adventure was Đại Việt clearly dominant; thus the term Nam tiến, if accurate at all, may only be applied from the beginning of the fifteenth century. Indeed, a new generation of scholars of Vietnam rejects entirely the concept of Nam tiến as a linear process." – p. 407: "...Only from the beginning of the fifteenth century is the traditional conception of a continuous push southward (Nam tiến) by the Vietnamese at all accurate.

- Vickery, Michael (2011), ""1620", A Cautionary Tale", in Hall, Kenneth R.; Aung-Thwin, Michael Arthur (eds.), New Perspectives on the History and Historiography of Southeast Asia: Continuing Explorations, Taylor & Francis, pp. 157–166, ISBN 978-1-13681-964-3

- Momorki, Shiro (2011), ""Mandala Campa" Seen from Chinese Sources", in Lockhart, Bruce; Trần, Kỳ Phương (eds.), The Cham of Vietnam: History, Society and Art, Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 120–137, ISBN 978-9-971-69459-3,

- ^ a b Lockhart 2011, p. 33.

- ^ a b Lockhart 2011, p. 36.

- ^ Lockhart 2011, p. 32.

- ^ Lockhart 2011, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Lockhart 2011, p. 13.

- ^ Lockhart 2011, p. 14.

- ^ Lockhart 2011, p. 15.

- ^ Lockhart 2011, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b Lockhart 2011, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Lockhart 2011, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Goscha 2016, p. 405.

- ^ Hayton, Bill (2020). The Invention of China. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-30023-482-4.

- ^ Churchman, Catherine (2016). The People Between the Rivers: The Rise and Fall of a Bronze Drum Culture, 200–750 CE. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-442-25861-7.

- ^ "David and Goliath: Vietnam confronts China over South China Sea energy riches - on Line Opinion - 16/6/2011".

- ^ Sutherland 2018, p. 11.

- ^ Lockhart 2011, p. 21.

- ^ a b Sutherland 2018, p. 149.

- ^ Lockhart 2011, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Nakamura & Sutherland 2019, p. 57.

- ^ Sutherland 2018, p. 167.

- ^ Lockhart 2011, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Lockhart 2011, p. 18.

- ^ Nakamura & Sutherland 2019, p. 52.

- ^ a b c Lockhart 2011, p. 39.

- ^ Lockhart 2011, p. 40.

- ^ Nakamura & Sutherland 2019, p. 55.

- ^ a b c Sutherland 2018, p. 126.

- ^ Sutherland 2018, p. 125.

- ^ Nakamura & Sutherland 2019, p. 53.

- ^ Nakamura & Sutherland 2019, p. 54.

- ^ Sutherland 2018, p. 47.

- ^ Goscha 2016, p. xxiv.

- ^ Goscha 2016, p. 406.

- ^ Greer, Tanner (January 5, 2017). "Cambodia Wants China as Its Neighborhood Bully". Foreign Policy.

- ^ Lockhart 2011, p. 37.

- ^ Hutt, David. "The Truth About Anti-Vietnam Sentiment in Cambodia". thediplomat.com. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ "The Cham: Descendants of Ancient Rulers of South China Sea Watch Maritime Dispute From Sidelines". Science. June 18, 2014. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ "On the Margins: Rights Abuses of Ethnic Khmer in Vietnam's Mekong Delta". Human Rights Watch. January 21, 2009. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Pischedda, S.; Barral-Arca, R.; Gómez-Carballa, A.; Pardo-Seco, J.; Catelli, M. L.; Álvarez-Iglesias, V.; Cárdenas, J. M.; Nguyen, N. D.; Ha, H. H.; Le, A. T.; Martinón-Torres, F. (October 3, 2017). "Phylogeographic and genome-wide investigations of Vietnam ethnic groups reveal signatures of complex historical demographic movements". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 12630. Bibcode:2017NatSR...712630P. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-12813-6. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5626762. PMID 28974757.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Bibliography

[edit]- Goscha, Christopher (2016). The Penguin history of Modern Vietnam. London, UK: Penguin Books, Limited. ISBN 978-0-14194-665-8.

- Lockhart, Bruce (2011), "Colonial and Post-Colonial Constructions of "Champa"", in Lockhart, Bruce; Trần, Kỳ Phương (eds.), The Cham of Vietnam: History, Society and Art, Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 1–54, ISBN 978-9-971-69459-3

- Nakamura, Rie; Sutherland, Claire (2019). "Shifting the Nationalist Narrative? Representing Cham and Champa in Vietnam's Museums and Heritage Sites". Museum & Society. 17 (1): 52–65. doi:10.29311/mas.v17i1.2819. S2CID 126594205 – via Northumbria University.

- Nguyen, Dinh Dau (2009), "The Vietnamese Southward Expansion, as Viewed Through the Histories", in Hardy, Andrew David; Cucarzi, Mauro; Zolese, Patrizia (eds.), Champa and the Archaeology of Mỹ Sơn (Vietnam), Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-9-9716-9451-7

- Sutherland, Claire (2018). Soldered States: Nation-building in Germany and Vietnam. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-1-52613-527-8.

- Vickery, Michael (2009), "A short history of Champa", in Hardy, Andrew David; Cucarzi, Mauro; Zolese, Patrizia (eds.), Champa and the Archaeology of Mỹ Sơn (Vietnam), Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 45–61, ISBN 978-9-9716-9451-7