Mary Jobe Akeley

Mary Jobe Akeley | |

|---|---|

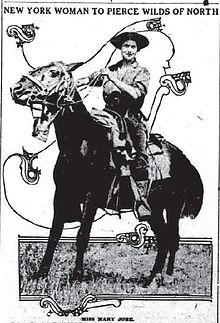

Mary Lenore Jobe around 1913, on horseback, depicting her as she traveled during many expeditions of British Columbia, Canada. From the Washington Herald. | |

| Born | Mary Lenore Jobe January 29, 1878 Harrison County, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | January 19, 1966 (aged 87) Mystic, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Burial place | Patterson Union Cemetery, Deersville, Ohio, U.S. |

| Education |

|

| Spouse | |

Mary Jobe Akeley (January 29, 1878 – January 19, 1966) was an American explorer, author, mountaineer, and photographer. She undertook expeditions in the Canadian Rockies and in the Belgian Congo. She worked at the American Museum of Natural History creating exhibits featuring taxidermy animals in realistic natural settings.[1][2] Akeley worked on behalf of conservation efforts, including her advocating for the creation of game preserves.[2][3] She founded Camp Mystic, an outdoor camp for girls.[4]

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

Akeley was born Mary Lenore Jobe on January 29, 1878, in Tappan, Harrison County, Ohio; the town was submerged below Tappan Lake in 1938.[5] (Although several printed sources, including her death certificate, give Akeley's birth year as 1888, the 1880 census and records at the Bryn Mawr College Archives confirm the 1878 date.[6]) Both of her parents were of English descent; her father was a veteran of the American Civil War.[6] Jobe attended Scio College from 1893 to 1897, graduating with a bachelor's degree, after which she taught at the elementary and high school level in Uhrichsville, Ohio. She went on to study at Bryn Mawr College from 1901 to 1903, while teaching at Temple University (1902–1903).[6] She taught history and civics at the normal school in Cortland, New York from 1903 to 1906, and then taught history at the Normal College of the City of New York (now Hunter College) from 1906 to 1916.[3][7] She earned a master's degree in History and English from Columbia University in 1909.[2][3][8]

During her time at Bryn Mawr, Jobe had her first opportunity to join a scientific expedition, joining a botanical expedition to the Selkirk Mountains in British Columbia. It was the first of many expeditions to the mountains of British Columbia.[8]

Mountaineering[edit]

Jobe was an accomplished mountain climber and was a member of the Alpine Club of Canada (ACC)[9] and the American Alpine Club.[1][2] From 1905 to 1918 she made ten expeditions to the Canadian Rockies. In 1913, she left her teaching job at Hunter to undertake an ethnographic expedition to study and photograph the Gitksan and Carrier Indians living between the Skeena River and the Peace River.[9]: 87 [10] Jobe concluded the summer of 1913 by meeting up with the annual camp of the ACC. There she heard of a distant mountain northwest of Mount Robson that had been glimpsed by members Samuel Prescott Fay and Donald 'Curly' Philips.[9]: 88 In 1914, she returned to the Canadian Rockies in search of the mountain, hiring Philips as her guide. At the time, Jobe called their destination "Big Ice Mountain", but in her later reports she referred to the peak as Mount Kitchi (from a Cree word meaning "mighty"[9]: 89 ); the mountain was officially named Mount Sir Alexander in 1916.[8][9][11] Joining Jobe and Philips on the expedition were Margaret Springate and Philips's assistant (and brother-in-law), Bert Wilkins.[8]

From their starting point near Mount Robson, the trip to and from Mount Sir Alexander took six weeks on foot and on horseback, during which time they saw very little evidence of prior human activity along the route. They reached the base of the peak on August 21, 1914, and reached their highest point on the mountain on August 25, stopping at about 8,000 feet (2,400 m) above sea level, well short of the summit, which Jobe estimated to be between 11,000 feet (3,400 m) and 12,000 feet (3,700 m). She took about 400 photographs on the trip. Upon her return, the New York Times hailed her as "the first white person and probably the first human being" to explore the remote mountain.[11] The Times article overstated some of Jobe's accomplishments on the expedition, and she wrote a letter to the editor a few days later to correct the errors.[12] Jobe reported on the expedition in both scholarly and popular publications after her return home.[13][14][15] In 1915, she took a commission from the Canadian government to explore and map the Fraser River in British Columbia and the Mount Sir Alexander glaciers.[16] She was joined by fellow ACC member Caroline Hinman; they again hired Curly Philips as a guide, as well as several of his staff as cooks and porters. Jobe and Philips became romantically involved during that summer.[9]: 96 The expedition made another attempt to climb Mount Sir Alexander, and came within about 30 metres (98 ft) of the summit.[9]: 98

In honor of Jobe's work in the Rockies, the Geographic Board of Canada renamed one of the south-eastern peaks of Mount Sir Alexander as Mount Jobe (2,271 metres (7,451 ft)) in 1925.[3][9]: 106 [17]

Camp Mystic[edit]

In 1914, Jobe purchased 45 acres near Mystic, Connecticut, and in 1916 she founded there the Mystic Camp for girls aged eight to eighteen.[16] Campers typically numbered "over 80 or more" at any one time,[18]: 1 and were mainly from wealthy and influential families. Campers included Hawai'ian princesses Abigail Kapiolani Kawānanakoa and Lydia Liliuokalani Kawānanakoa, as well as the daughters of artist Howard Chandler Christy, radio sportscaster Grantland Rice, cookbook author Ida Bailey Allen, and publisher Bernarr Macfadden.[18]: 2 Advertisements for the camp appeared in popular magazines such as Vogue and St. Nicholas.[18]: 2 [19]: 5 A 1916 advertisement in Scribner's Magazine promised campers experience with backcountry camping, boating, swimming, horseback riding, dancing, music, drama, and field athletics.[20] Jobe owned a 30-meter (98 ft) boat that she used to take campers to Mystic Island (now called Ram Island (Connecticut)) in Fishers Island Sound.[9]: 101 In 1921, Jobe purchased the southern half of Mystic Island, and later bought the rest of the island.[18]: 5 In addition to giving girls first-hand experience with the outdoors, the camp was visited by famous explorers and naturalists of the day such as Vilhjalmur Stefansson, Herbert Spinden, George Cherrie, and Martin and Osa Johnson.[6][18]: 7 [19] The fee for campers in 1923 was $375.[19]: 5

In a brochure for the camp, Jobe wrote that "girls find health, happiness and their highest development out-of-doors, where they leave behind them the artificialities of towns and cities for the joyous realities of the wooded hills and seashore."[8]: 298 Another stated that "girls of today have a right to freedom, health, and happiness."[19]: 5 Although she did not describe herself as a feminist or suffragist, she has been so identified by others, and she declared herself to be "very much in sympathy with the [suffrage] movement."[19]: 4

The camp closed in 1930 due to the Great Depression.[21] She remained the camp's director throughout its existence.[19]: 5

Marriage and African expeditions[edit]

In 1920, fellow explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson introduced Jobe to naturalist and taxidermist Carl Akeley. Akeley was married to Delia Akeley at the time, but Mary and Carl began an affair. Delia and Carl concluded a bitter divorce in 1923, and Jobe married Akeley on October 28, 1924, at All Souls Episcopal Church in New York City.[7][8][16][22] He was deeply involved with a project to collect specimens for a new Africa exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History, and she wrote later that he expected Mary to abandon her own work and devote her time to his African project. Although she described this as "startling," she largely complied.[19]: 6 In 1926, she accompanied him on his fifth expedition in Africa (and her first) to collect specimens. On the trip, known as the Akeley-Eastman-Pomeroy Expedition, he became sick on Mount Mikeno of the Belgian Congo and died of a fever.[2][20][23] She completed the expedition, mapping parts of the Belgian Congo as well as Kenya and Tanzania, and collecting plant specimens, taking hundreds of photographs.[3] Upon her return to the United States, the museum named her to be her husband's successor as the Special Adviser to the development of their African Hall, a role she held until 1938.[8] In that role, she lectured, wrote, and raised funds for the hall.[19]: 8 The hall was renamed in Carl Akeley's honor in 1936.[3][22] (Upon her death, the New York Times incorrectly stated that the hall was named after Mary.)[2][22]

Part of the purpose of the 1926 expedition was to map the area around the new Belgian game preserve Parc National Albert. Following the end of the expedition, Akeley collaborated with Belgian zoologist Jean Marie Derscheid to complete a report on the park. She was awarded the Cross of the Knight, Order of the Crown by the Belgian king for her efforts. From 1929 to 1936, Akeley also served as the American secretary for an international committee organized to preserve the Park.[16]

Akeley returned to Africa in 1935 to Transvaal Province, Southern Rhodesia, and Portuguese East Africa, as well as Kruger National Park in South Africa. There she photographed Zulu people and Swazi people.[3] She returned again in 1947 at the behest of the Belgian crown to inspect the wildlife reserves in the Congo, and to film endangered species.[3]

Photography[edit]

Akeley began her photographic work in the Canadian Rockies on a 1909 expedition led by Herschel C. Parker for the Canadian Topographical Survey.[19]: 1 The results of her early work are preserved on hand-colored lantern slides she used when lecturing about her expeditions.[10] Her ethnographic work records people and their customs, including ceremonial objects.[10] Her work in Africa focused on wildlife, as well as on their environment.[8]: 298 [10] On the 1926 trip to the Congo, her husband Carl was in the process of developing a gorilla scene for the American Museum of Natural History. Carl died before completing the research for the exhibit, so Mary used his reference photos to identify the particular spot he was trying to re-create, taking hundreds of photos of the scene, both of individual plant species and the larger scene. She also collected specimens of the plants.[22]: 112 She also took a side-trip to Lake Hannington in Kenya to photograph flamingos.[16] Her photos were used in the Akeley African Hall of the American Museum of Natural History.[6]

Over 2000 of Akeley's lantern slides survive.[10] Her photographic output is preserved at the American Museum of Natural History and the Mystic River Historical Society.[8][10] Biographer Dawn-Starr Crowther describes Akeley's photography as representing an important period for women, revealing Akeley to be "resolving for herself the dilemma of many women who were struggling to shake off the tenets of Victorianism and find meaningful ways through which to express themselves."[10] She describes Akeley's photographic style as "straight-forward... direct and powerful," as well as "stable and balanced," documenting the people and places she encountered on her expedition.[19]: 14

Authorship and public life[edit]

Akeley spoke frequently about her work. In 1912, she is reported to have given over 40 lectures about her early expeditions.[19]: 3 Following her return from Africa in 1927 and throughout much of the rest of her life, Akeley worked for conservation causes, lectured extensively, and appeared on the radio. She dined at the White House with first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who noted Akeley's conservation and education work in Roosevelt's daily syndicated newspaper column, "My Day".[7]: 5–6 [24]

Akeley was the author of seven books, some of them posthumously co-authored with her husband by making use of materials he had written before his death. The first book, Carl Akeley's Africa (1929), was Mary's account of the expedition that cost Carl Akeley his life, documenting the animals and native peoples encountered on the expedition to the Congo. The following year, she published Adventures in the African Jungle (1930), with Carl listed as a co-author, in keeping a plan they had made while both were still alive. Chapters are signed either by Mary or Carl; Mary assembled Carl's chapters from his field notes and from stories related by his friends. Her chapters include her accounts of experiences from their journey to the Congo, both before and after his death on the expedition.[25] Lions, Gorillas, and their Neighbors (1932) also lists Carl as a co-author and also covers their expedition, using the story to convey a message of conservation, noting the decline in large animal populations over the previous 30 years. A review in the Times of London of the book tells a thrilling tale of the hunt, but emphasizes that their purpose was scientific, not thrill-seeking. The reviewer writes, "they show how greater and more lasting pleasure [can] be had by restrained and intelligent hunt than by indiscriminate killing... the big game of Africa is presented as something of real value to the human race."[26]

In The Wilderness Lives Again, Akeley recounts her late husband's work as a taxidermist, including his expeditions in Africa. A review in The New York Times calls particular attention to the story of development of the gorilla exhibit for the American Museum of Natural History, describing both the taxidermy process and the moving effect of the life-like exhibit.[27]

Congo Eden (1950) was published following Akeley's final trip to Africa in 1947, and relates the story of that journey.[28] Historian Jeannette Eileen Jones identifies the "Eden" of the book's title as part of Carl and Mary Akeley's campaign to challenge the public perception of Africa as "hellish" or "dark."[29]

Death[edit]

Akeley's health declined toward the end of her life, with Akeley suffering from hip problems and arthritis. She was in and out of hospitals and nursing homes from 1959 to 1966.[19]: 12 Akeley lived her last years at the former site of Camp Mystic, decorated with souvenirs of her African adventures, retaining an independent spirit despite illness and a "failing mind."[19]: 12 She died of a stroke in 1966 at the Mary Elizabeth Convalescent Home in Mystic, Connecticut[3][9]: 106 [18]: 11 [22] Although she had expressed a wish to be cremated and buried next to her late husband on Mt. Mikeno, she was buried in Deersville, Ohio near where she was born, in the same cemetery as her parents.[22]: 112 Following her death, the former camp became the Peace Sanctuary under the stewardships of the Mary L. Jobe Akeley Trust & Peace Sanctuary. It is now maintained by the Denison Pequotsepos Nature Center.[30]

Akeley left an extensive record of her work. Her papers are held in the Mary L. Jobe Akeley Collection at the Mystic River Historical Society,[16] the American Museum of Natural History,[31] and at Connecticut College.[4]

Books[edit]

- Carl Akeley's Africa; the account of the Akeley-Eastman-Pomeroy African Hall Expedition of the American Museum of Natural History (1929)[32]

- Adventures in the African Jungle (1930)[33]

- Lions, Gorillas, and their Neighbors (1932)[34]

- The Swan Song of Old Africa (1932)[35]

- The Restless Jungle (1936)[36]

- The Wilderness Lives Again (1940)[37]

- Rumble of a Distant Drum: a True Story of the African Hinterland (1946)[38]

- Congo Eden (1950)[39]

Awards and honors[edit]

- Knight of the Order of the Crown by King Albert of Belgium for work in the Congo[1][16][20]

- Mount Jobe in the Canadian Rockies named in her honor by the Canadian government[2]

- Honorary Doctorate from Mt. Union College in 1930[10]

- Inducted into the Ohio Women's Hall of Fame in 1979[40]

- Inducted into the Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame, 1994[41]

Memberships[edit]

- Royal Geographic Society, Fellow, 1915[9]: 106

- American Alpine Club[2]

- Alpine Club of Canada[2]

- French Alpine Club[2]

- Society of Women Explorers[2]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Hall, Henry S. (1967). "Mary Jobe Akeley". American Alpine Journal: 452.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "MARY J. AKELEY, AN EXPLORER, 80; Author and African Wildlife Expert for Museum Dies". The New York Times. 1966-07-22. p. 31. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Duncan, Joyce (2002). "Mary Lenore Jobe Akeley (1878–1966)". Ahead of their time : a biographical dictionary of risk-taking women. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0313316609. OCLC 47283091.

- ^ a b "Mary Jobe Akeley Papers". collections.conncoll.edu. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- ^ "Akeley, Mary Jobe (1878–1966)". encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- ^ a b c d e McCay, Mary (1980). "Akeley, Mary Lee Jobe". In Sicherman, Barbara; Green, Carol Hurd (eds.). Notable American women : the modern period : a biographical dictionary. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 8–10. ISBN 978-0674627321. OCLC 6487187.

- ^ a b c Erving E., Beauregard (2000). "Mary Jobe Akeley: Bicontinental Explorer". Notables of Harrison County, Ohio. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press. pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-0773478411. OCLC 42823740.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gilmartin, Patricia (November 1990). "Mary Jobe Akeley's Explorations in the Canadian Rockies". The Geographical Journal. 156 (3): 297–303. doi:10.2307/635530. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 635530.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Smith, Cyndi (1989). "Mary Jobe Akeley". Off the beaten track: Women adventurers and mountaineers in western Canada. Jasper, Alta.: Coyote Books. pp. 80–106. ISBN 978-0969245728. OCLC 24009607.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Crowther, Dawn-Starr (1995). "Akeley, Mary L. Jobe (1878-1966)". North American women artists of the twentieth century : a biographical dictionary. Heller, Jules., Heller, Nancy G. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0824060497. OCLC 31865530.

- ^ a b "Miss Jobe Climbs a Lost Mountain; New York Teacher Back from Exploring Trip in the Canadian Rockies. Face Peril and Hardship Woman Companion and Two Guides Scale Dizzy Heights and Run Short of Food". The New York Times. 1914-09-13. p. 12. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- ^ Jobe, Mary L. (1914-09-17). "Did Not Include an Attempt to Ascend Mt. Robson". The New York Times. p. 8. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- ^ Jobe, Mary L. (1915). "MT. Kitchi: A New Peak in the Canadian Rockies". Bulletin of the American Geographical Society. 47 (7): 481–497. doi:10.2307/201432. ISSN 0190-5929. JSTOR 201432.

- ^ Jobe, Mary L. (1915). "The expedition to 'Mt Kitchi': a new peak in the Canadian Rockies". Canadian Alpine Journal. 6: 188–200.

- ^ Jobe, Mary L. (2015). "My quest in the Canadian Rockies: locating a new ice-peak". Harper's Magazine. 130: 813–825.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gale, Robert L. (1999). "AKELEY, Mary Leonore Jobe". American national biography. Vol. 1. Garraty, John A. (John Arthur), Carnes, Mark C. (Mark Christopher), American Council of Learned Societies. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 204–205. ISBN 978-0195206357. OCLC 39182280.

- ^ "Mount Jobe". cdnrockiesdatabases.ca. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- ^ a b c d e f Kimball, Carol W. (February 1978). "Camp Mystic in the Good Old Summertime". Historical Footnotes: Bulletin of the Stonington Historical Society. 15 (2): 1–11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Crowther, Dawn-Starr (1989). Mary L. Jobe Akeley. History of Photography Monograph Series. Tempe, AZ: School of Art at Arizona State University. OCLC 19829373.

- ^ a b c Sommer, Carol (2015-09-12). "Legacy of Mystic's Mary Jobe Akeley has global reach". The Day. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- ^ "Mystic Explorer Mary L. Jobe, A Life Well Lived". Groton, CT Patch. 2011-03-04. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- ^ a b c d e f Preston, Douglas J. (1986). "In Deepest Africa". Dinosaurs in the attic : an excursion into the American Museum of Natural History. New York: Ballantine Books. pp. 96–115. ISBN 978-0345347329. OCLC 17346909.

- ^ "Obituary: Mrs. Mary Jobe Akeley". The Geographical Journal. 132 (4): 597–598. December 1966. JSTOR 1792629.

- ^ Roosevelt, Eleanor (1938-04-14). "My Day". The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Digital Edition. The George Washington University. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- ^ "The Africa of Mr. and Mrs. Carl Akeley". New York Times Book Review. 1931-02-01. p. BR 13. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- ^ "African Big Game". The Times. No. 46580. 1933-10-20. p. 18.

- ^ Thompson, Ralph (1940-09-10). "Books of the Times". The New York Times. p. 21. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- ^ "Mrs. Mary Akeley". The Times. No. 56691. 1966-07-23. p. 15.

- ^ Jones, Jeannette Eileen (2000). ""In Brightest Africa": Naturalistic Constructions of Africa in the American Museum of Natural History, 1910-1936". In Mengara, Daniel M (ed.). Images of Africa: stereotypes & realities. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press. pp. 195–208. ISBN 9780865439061. OCLC 931288078.

- ^ "The Peace Sanctuary • The Mystic Wave". The Mystic Wave. 2013-11-07. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- ^ Akeley, Mary L. Jobe; Akeley, Carl Ethan. Mary Jobe Akeley papers. American Museum of Natural History, American Museum of Natural History.

- ^ Akeley, Mary L. Jobe (1929). Carl Akeley's Africa; the account of the Akeley-Eastman-Pomeroy African Hall Expedition of the American Museum of Natural History. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co. OCLC 415066.

- ^ Akeley, Carl Ethan; Akeley, Mary L. Jobe (1930). Adventures in the African jungle. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co. OCLC 1052709244.

- ^ Akeley, Carl Ethan; Akeley, Mary L. Jobe (1932). Lions, gorillas and their neighbors. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co. OCLC 1306847.

- ^ Akeley, Mary L. Jobe (1932). The Swan Song of Old Africa. New York: Am. Mus. of Nat. Hist. OCLC 31833730.

- ^ Akeley, Mary L. Jobe (1936). Restless jungle. New York: R.M. McBride & Co. OCLC 1097564.

- ^ Akeley, Mary L. Jobe (1946). The wilderness lives again: Carl Akeley and the great adventure. New York: Dodd, Mead. OCLC 1097636.

- ^ Akeley, Mary L. Jobe (1946). Rumble of a distant drum; a true story of the African hinterland. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co. OCLC 1621128.

- ^ Akeley, Mary Lee Jobe (1950). Congo Eden.: a comprehensive portrayal of the historical background and the scientific aspects of the Great Game sanctuaries of the Belgian Congo with the story of six months pilgrimage throughout that most primitive region in the heart of the African : continent. New York: Dodd, Mead. OCLC 186810598.

- ^ "Mary Jobe Akeley". Ohio Women's Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24.

- ^ "Mary Jobe Akeley". Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

External links[edit]

- Peace Sanctuary at the site of Akeley's former home and camp

- Mary Jobe Akeley at Find a Grave