Triple E-class container ship

Triple E-class container ship Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Builders | Daewoo Shipbuilding |

| Operators | Maersk |

| Preceded by | E class |

| Planned | 31 |

| Building | 0 |

| Completed | 31 |

| Active | 31 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Container ship |

| Tonnage | 196,000 DWT |

| Displacement | 55,000 tonnes (empty)[1] |

| Length | 399.2 m (1,309 ft 9 in) |

| Beam | 58.6 m (192 ft 3 in) |

| Draft | 16 m (52 ft 6 in) |

| Decks | 4 |

| Propulsion | Twin MAN 8S80ME-C9 engines, 29,680 kilowatts (39,800 hp) each at 73 RPM |

| Speed | Design cruise: 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) Max: 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph) |

| Capacity | 18,270 TEU |

| Notes | Cost $185 million[1] |

| General characteristics (2nd generation) | |

| Type | Container ship |

| Tonnage | 210,019 DWT |

| Length | 399.2 m (1,309 ft 9 in) |

| Beam | 58.6 m (192 ft 3 in) |

| Draft | 17 m (55 ft 9 in) |

| Propulsion | Twin MAN engines, 31,000 kilowatts (42,000 hp) each |

| Capacity | 20,568 TEU |

The Triple E class is a family of very large container ships with a capacity of more than 18,000 TEUs, which are owned and operated by Maersk Line.

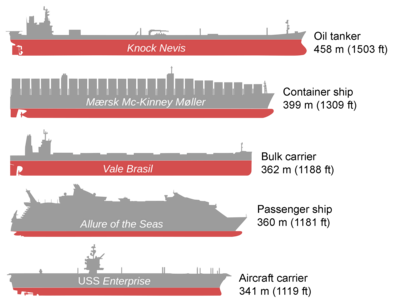

With a length of 399.2 m (1,309 ft 9 in), when they were built they were the largest container ships in the world, but were subsequently surpassed by larger ones such as CSCL Globe.[2][3]

In February and June 2011, Maersk Line awarded Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering two US$1.9 billion contracts ($3.8bn total) to build twenty ships of this class.

The name "Triple E" is derived from the class's three design principles: "Economy of scale, Energy efficiency, and Environmental impact improvement".

The ships are 399.2 metres (1,309 ft 9 in) long and 59 metres (193 ft 7 in) wide. While only 3 metres (9 ft 10 in) longer and 4 metres (13 ft 1 in) wider than the Mærsk E class, the Triple E ships are able to carry 2,500 more containers. With a beam of 59 metres, they are too wide to traverse the Panama Canal, but can easily transit the Suez Canal.

One of the class's main design features is its dual 29.68-megawatt (39,800 hp), eight-cylinder, ultra-long stroke two-stroke diesel engines, driving two propellers at a design speed of 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph). This class is by design slower than its predecessors, using a strategy known as slow steaming expected to lower fuel consumption by 37% and carbon dioxide emissions per container by 50%. The Triple E design helped Maersk win a "Most Sustainable Ship Operator of the Year" award in July 2011.

Maersk plans to use the ships to service routes between Europe and Asia, projecting that Chinese exports will continue to grow. European-Asian trade represents the company's largest market; thus it already has 100 ships serving the route.

Orders and history

[edit]In February 2011 Maersk announced orders for a new "Triple E" family of container ships with a capacity of 18,000 TEU, with an emphasis on lower fuel consumption.[4] They were built by Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering (DSME) in South Korea; the initial order, for ten ships, was valued at US$1.9 billion (2 trillion Korean Won);[5] Maersk had options to buy a further twenty ships.[6] In June 2011 Maersk announced that 10 more ships had been ordered for $1.9bn,[7] but an option for a third group of ten ships would not be exercised.[8] Payment of the ship is "tail-heavy": 40% while the ship is being built, and the remaining 60% paid on delivery.[9] Deliveries were scheduled to begin in 2013.[10] Maersk negotiated a two-year warranty, whereas the standard is one year.[1]

Prior to 2010, many Maersk container ships had been built at Maersk's Odense Steel Shipyard in Denmark, but Asian builders had become more competitively priced.[11] Maersk had approached several different builders in Asia, having ruled out European shipbuilders on grounds of cost, and Chinese on technological grounds.[12][13] DSME builds three Triple-Es at a time, and it takes little more than a year to produce a ship.[1]

Investment in more efficient ships helped Maersk win the "Sustainable Ship Operator of the Year" award from Petromedia Group's on-line publication sustainableshipping.com in July 2011.[14]

In 2015, Maersk ordered an additional series of eleven 20,568 TEU second-generation Triple E-class ships, due to be delivered from 2017 onwards. The first ship is the Madrid Maersk. She went on her maiden voyage to Antwerp.[15]

Ships

[edit]| Maersk Triple E class | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Ship name | Yard number | IMO number | Delivered | Status | Ref. |

| 1 | Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller | 4250 | 9619907 | 2 July 2013 | In service | [16] |

| 2 | Majestic Mærsk | 4251 | 9619919 | 2 August 2013 | In service | [17] |

| 3 | Mary Mærsk | 4252 | 9619921 | 30 August 2013 | In service | [18] |

| 4 | Marie Mærsk | 4253 | 9619933 | 18 October 2013 | In service | [19] |

| 5 | Madison Mærsk | 4254 | 9619945 | 6 January 2014 | In service | [20] |

| 6 | Magleby Mærsk | 4255 | 9619957 | 10 February 2014 | In service | [21] |

| 7 | Maribo Mærsk | 4256 | 9619969 | 7 April 2014 | In service | [22] |

| 8 | Marstal Mærsk | 4257 | 9619971 | 20 May 2014 | In service | [23] |

| 9 | Matz Mærsk | 4258 | 9619983 | 10 June 2014 | In service | [24] |

| 10 | Mayview Mærsk | 4259 | 9619995 | 25 July 2014 | In service | [25] |

| 11 | Merete Mærsk | 4262 | 9632064 | 22 August 2014 | In service | [26] |

| 12 | Mogens Mærsk | 4263 | 9632090 | 17 September 2014 | In service | [27] |

| 13 | Morten Mærsk | 4264 | 9632105 | 10 November 2014 | In service | [28] |

| 14 | Munkebo Mærsk | 4265 | 9632117 | 18 December 2014 | In service | [29] |

| 15 | Maren Mærsk | 4266 | 9632129 | 29 December 2014 | In service | [30] |

| 16 | Margrethe Mærsk | 4267 | 9632131 | 13 April 2015 | In service | [31] |

| 17 | Marchen Mærsk | 4268 | 9632143 | 27 May 2015 | In service | [32] |

| 18 | Mette Mærsk | 4269 | 9632155 | 6 May 2015 | In service | [33] |

| 19 | Marit Mærsk | 4270 | 9632167 | 5 June 2015 | In service | [34] |

| 20 | Mathilde Mærsk | 4271 | 9632179 | 30 June 2015 | In service | [35] |

| Maersk Triple E class (2nd Generation) | ||||||

| 21 | Madrid Mærsk | 4302 | 9778791 | 7 April 2017 | In service | [36] |

| 22 | Munich Mærsk | 4303 | 9778806 | 15 June 2017 | In service | [37] |

| 23 | Moscow Mærsk | 4304 | 9778818 | 14 July 2017 | In service | [38] |

| 24 | Milan Mærsk | 4305 | 9778820 | 13 September 2017 | In service | [39] |

| 25 | Monaco Mærsk | 4306 | 9778832 | 30 October 2017 | In service | [40] |

| 26 | Marseille Mærsk | 4307 | 9778844 | 4 January 2018 | In service | [41] |

| 27 | Manchester Mærsk | 4308 | 9780445 | 8 January 2018 | In service | [42] |

| 28 | Murcia Mærsk | 4309 | 9780457 | 28 February 2018 | In service | [43] |

| 29 | Manila Mærsk | 4310 | 9780469 | 29 March 2018 | In service | [44] |

| 30 | Mumbai Mærsk | 4311 | 9780471 | 3 May 2018 | In service | [45] |

| 31 | Maastricht Mærsk | 4312 | 9780483 | 10 January 2019 | In service | [46] |

| Source: Equasis,[47] grosstonnage[48] | ||||||

-

Section of a Triple E-class ship, under construction

-

Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller, passing through the Suez Canal

-

Manila Maersk inbound Hamburg, Germany in June 2018

-

Monaco Maersk of the 2nd generation (2018 in Hamburg)

Design

[edit]

Specifications

[edit]- Capacity: 18,270 TEU[49][50]

- Length: 399.2 metres

- Draft: 14.5 metres

- Beam: 59 metres

- Height: 73 metres

- Optimum speed: 19 knots (35 km/h)

- Top speed: 25 knots (46 km/h)[51]

- Deadweight: 165,000 tonnes

- In the first 10 vessels engines are twin MAN 8S80ME-C9.2 engines, 8-cylinders, 800 mm bore, 3450 mm stroke, rated at 29.7 MW @ 73 rpm each, with fuel consumption of 168 g/kWh[52] (80 m3 (21,200 US gal) per day)[53]

- Propellers: Twin propellers, with 4 blades, 9.8 m in diameter[54]

Propulsion

[edit]Unlike conventional single-engined container ships, the new class of ships has a twin-skeg design: it has twin diesel engines, each driving a separate propeller. Usually, a single engine is more efficient,[12] but using two propellers allows a better distribution of pressure, which increases the propeller efficiency more than the disadvantage of using two engines.[55]

The engines have waste heat recovery (WHR) systems; these are also used in 20 other Mærsk vessels including the eight E-class ships. The name "Triple E class" refers to three design principles: "Economies of scale, energy efficiency, and environmental impact improvement".[49]

The twin-skeg principle also means that the engines can be lower and further back, allowing more room for cargo. Maersk requires ultra-long stroke two-stroke engines running at 80 rpm (versus 90 rpm in the E class);[56] but this requires more propeller area for the same effect, and such a combination is only possible with two propellers due to the shallow water depth of the desired route.[13][54]

A slower speed of 19 knots is designed, compared to the 23–26 knots of similar ships.[13] The top speed would be 25 knots, but steaming at 20 knots would reduce fuel consumption by 37%, and at 17.5 knots fuel consumption would be halved.[51] These slower speeds would add 2–6 days to journey times.[57]

The various environmental features are expected to cost $30 million per ship, of which the WHR is to cost $10 million.[12] Carbon dioxide emissions, per container, are expected to be 50% lower than emissions by typical ships on the Asia-Europe route[58] and 20% lower than Emma Maersk.[59] These are the most efficient container ships per TEU in the world. A cradle-to-cradle design principle was used to improve scrapping when the ships end their life.[60]

The Madrid Maersk and subsequent ships in the series use electric motor-generator sets to improve operation.[61]

Dimensions and layout

[edit]

The ships were the longest in the world.[62][63] They have since been surpassed by other container ships, like the MV Barzan, exactly 400 m (1,312 ft) long. The Triple E series and its competitors often leapfrog each other for capacity as the types are updated with new ships larger than their sisters. For a while, Madrid Maersk with 20,568 TEU had the world's largest capacity until superseded by the 21,413 TEU OOCL Hong Kong.[64]

The hull is more 'boxy' with a U cross-section compared to the V-shape of Maersk's E class; this allows more containers to be stored at lower levels so, while the Triple E class is only 3 m (9.8 ft) wider and 4 m (13 ft) longer, it can carry 2,500 (16%) more containers. The Triple E class can carry 23 rows of containers compared to 22 of the E class, which makes better use of the reach of current terminal cranes.[12]

The deckhouse is relatively further forward, whilst the engines are to the rear; similar to CMA CGM's Explorer class of containerships, also built by Daewoo.[65] The forward deckhouse allows containers to be stacked higher in front of the bridge, further increasing capacity while maintaining forward visibility sufficient to comply with SOLAS regulation V/22.

The Triple E-class vessels are operated by a crew of 13, while the even larger Globe class requires 31 on board.[citation needed]

When the class was ordered, no port in the Americas could handle ships of their size.[66] However, the following suitable ports include Shanghai, Ningbo, Xiamen, Qingdao, Yantian, Hong Kong, Tanjung Pelepas, Singapore, and Colombo in Asia, and Rotterdam, Gothenburg, Wilhelmshaven,[67] Bremerhaven, Southampton, London Gateway, Le Havre, Felixstowe, Gdańsk, Antwerp, and Algeciras in Europe. The ships will be too large for the New Panamax-sized locks on the Panama Canal,[66] and their main route is expected to be Asia-Europe (through the Suez Canal).[68] The draft of the Triple E class is 14.5 metres (48 ft), less than the SuezMax requirement of 55.9 ft (17.0 m) at 59 m (194 ft) beam.[69] Handling equipment at ports was the main constraint on size, rather than the dimensions of canals or straits.[12] The container port handling speed can be 29 moves per hour in Tanger-Med,[70] or 37 in Rotterdam (215 per ship).[71] Anchor and mooring winch systems are being supplied by TTS Marine.[72]

Market

[edit]Maersk Line planned to use the ships on routes between Europe and Asia.[63] In 2008, there was a reduction in demand for container transport caused by economic recessions in many countries. This left shipping lines in financial difficulties in 2009, with surplus capacity in their ships. Some ships were laid up or scrapped. However fortunately, there was a sudden resurgence of demand for container transport in 2010; Maersk Line posted its largest ever profit,[73] and orders for new ships increased, leading to fresh concerns about future overcapacity.[74] The market was still characterized by overcapacity and decreasing prices for new ships in 2013. China Shipping Container Lines ordered five ships with a capacity of 18,400 TEU[75] from Hyundai Heavy Industries,[76] topping the Triple E class, with delivery from late 2014.[75] United Arab Shipping Company has ordered (also from Hyundai) five slightly larger ships and five ships larger than the Maersk E class.[76] Several other larger ships have been ordered by the industry.[77]

Slow steaming, as used by the Triple E class, is one way of maximizing capacity and reducing fuel consumption. The order for many big ships is a gamble on Maersk's part that Chinese exports will continue to grow.[63] Lack of market growth in the second half of 2012 caused Maersk to postpone a decision on how to use the Triple E class. Five Triple E-class vessels were to be delivered in 2013, with an impact sometime in 2014 with eight or nine Triple E-class vessels operating.[78] Maersk already uses approximately 100 ships on the Asia-Europe route, which is their most important.[57] SeaIntel expects about 46 ships with more than 10,000 TEU each to be delivered worldwide in 2013.[79] The construction of newer, larger ships has influenced development plans at ports such as London Gateway and JadeWeserPort in Wilhelmshaven (Germany),[80] and Algeciras and Tanjung had bigger cranes installed. The maximum number of TEUs carried in one trip was 18,024 in January 2015, in Algeciras, Spain.[81]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Bennett, Drake. "Manufacturing Holy Ship", Bloomberg Businessweek. 5 September 2013. Accessed: 22 September 2013.

- ^ "MSC Zoe takes bow in triple-first". Lloyds List. 3 August 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ "MSC Oscar becomes the world's largest boxship". Lloyds List. 11 December 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ "NORDIC ROUNDUP: Maersk Orders 10 Container Carriers". Wall Street Journal (subscription required). 22 February 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ "Daewoo says to win 2 trln won order from Maersk". Reuters. 20 February 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ Vidal, John (21 February 2011). "Maersk claims new 'mega containers' could cut shipping emissions". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ "Maersk Line contracts additional 10 Triple-E vessels". Baird Maritime. 27 June 2011. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Maersk expects to limit Triple-E fleet to 20 vessels". Lloyd's List. 27 June 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ Pay on delivery Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine Dagbladet Børsen, 22 February 2011. Accessed: 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Maersk Orders Up to 30 of Biggest Container Ships on Trade". Business Week. 22 February 2011. Archived from the original on February 23, 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Daewoo wins $2bn Maersk order, talks on $2bn". Daily Times. 19 February 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Maersk orders 10 green mega-boxships Archived 2011-02-27 at the Wayback Machine The Motorship, 21 February 2011. Accessed: 22 February 2011.

- ^ a b c New Mærsk Triple-E ships worlds largest and most efficient; waste heat recovery and ultra long stroke engines contribute to up to 50% reduction in CO2/container moved Dispatch Control, 21 February 2011. Accessed: 22 February 2011.

- ^ "Maersk Line gewinnt Preis als Nachhaltiger Schiffsbetreiber des Jahres". Fruchtportal.de. 31 July 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ "Maersk Line orders 11 ultra-large container vessels". Lloyds List. 2 June 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ "Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller (13232687)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Majestic Mærsk (13232688)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Mary Mærsk (13232689)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Marie Mærsk (13232690)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Madison Mærsk (14232691)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Magleby Mærsk (14232692)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Maribo Mærsk (14232695)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Marstal Mærsk (14232696)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Matz Mærsk (14232697)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Mayview Mærsk (14232698)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Merete Mærsk (14236506)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Mogens Mærsk (14236507)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Morten Mærsk (14236508)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Munkebo Mærsk (14236509)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Maren Mærsk (14236510)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Margrethe Mærsk (15236511)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Marchen Mærsk (15236512)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Mette Mærsk (15236513)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Marit Mærsk (15236514)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Mathilde Mærsk (15236515)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Madrid Mærsk (17265397)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Munich Mærsk (17265398)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Moscow Mærsk (17265399)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Milan Mærsk (17265400)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Monaco Mærsk (17265401)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Marseille Mærsk (18265402)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Manchester Mærsk (18265403)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Murcia Mærsk (18265404)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- ^ "Manila Mærsk (18265405)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- ^ "Mumbai Mærsk (18265406)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ^ "Maastricht Mærsk (19265407)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2019-04-28.

- ^ Equasis.org

- ^ grosstonnage.com

- ^ a b "Maersk orders largest, most efficient ships ever". Maersk. 21 February 2011. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Largest container ship will be 16% larger and 20% less CO2and 35% more fuel efficient". Next Big Future. 21 February 2011. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ a b "Maersk Orders 10 Triple-E Class 18,000TEU Container Ships". Maritime Propulsion. 22 February 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Maersk Line receives record boxship MAERSK MC-KINNEY MOLLER (18,270 teu)". linervision. 2 July 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ "World's Biggest Ship: The $185M Maersk Triple-E" (Video) Bloomberg Businessweek. 5 September 2013. Accessed: 22 September 2013.

- ^ a b "Maersk orders ten 18,000 TEU Triple-E containerships". Marinelog. 21 February 2011. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ Maersk megaship with two propellers Archived 2011-02-23 at the Wayback Machine (in Danish) Ing.dk, 21 February 2011. Accessed: 22 February 2011.

- ^ "Changes of course in boxship power". The Motorship. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ^ a b "Maersk mega ships too big for US". Copenhagen Post. 22 February 2011. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Corporate Responsibility and Sustainability News: Huge Maersk Triple-E Ships Get "E" for Effort, and Expense". Environmental News Network. 23 February 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Mærsk revolutionerer containermarkedet". Dagbladet Børsen. 21 February 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Here it comes Archived 2013-11-22 at the Wayback Machine" page 18, Maersk Post June 2013. Accessed: 22 September 2013.

- ^ "GE's Fuel-Efficient Marine Technology Powers the World's Largest Container Vessels by Maersk - Humans At Sea". 5 October 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ REVIEW OF MARITIME TRANSPORT 2011 p37, UNCTAD 2011. Accessed: 7 May 2012.

- ^ a b c "The Danish Armada". The Economist. February 21, 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ "Madrid Maersk Snatches Record from MOL Triumph". Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ "Ship of the Day: CMA CGM CHRISTOPHE COLOMB – Characteristics and pictures of a new ship entering Rotterdam every day". 15 July 2010. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ a b Frank Pope. "Bigger, cleaner, slower – the new giants of the seas" Mirror&Archive The Times, February 22, 2011. Accessed: 6 December 2013.

- ^ "Second Maersk Line's Triple-E-Class Vessel to Call at EUROGATE in Wilhelmshaven (Germany)". World Maritime News. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ^ "Maersk ordert 18.000-TEU-Frachter". Thb.info. 22 February 2011. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Suez Canal Authority – Rules of Navigation, table No. 4" (PDF). Suez Canal Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-04. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ "Maersk’s Triple E Ship Calls at Morocco’s Tanger-Med Port" Journal of Commerce, 9 September 2013. Accessed: 22 September 2013. Archived on 29 October 2013.

- ^ "Maasvlakte I retrofits cranes" APM Terminals

- ^ "Winch order for mega-boxships". The Motorship. Archived from the original on 5 June 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "Maersk posts best profit ever". Finance News. 2011. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Container Shipping Overview", Container Shipping Overview, China Shipping Report, Business Monitor International, 2011, pp. 7–26

- ^ a b "Vessel ordering mania – why? Archived 2014-12-19 at the Wayback Machine" Container Insight Weekly, 30 June 2013. Accessed: 1 September 2013.

- ^ a b "UASC places US$1.4B boxship contract Archived 2014-02-21 at the Wayback Machine" World Cargo News, 30 August 2013. Accessed: 1 September 2013.

- ^ Stensvold, Tore (10 April 2015). "Samsung setter ny rekord for containerskip - igjen" [Samsung sets new record - again]. Teknisk Ukeblad. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ^ KRISTIANSEN, Tomas (11 March 2013). "Søren Skou: Vi regner først med Triple-E effekt i 2014". ShippingWatch. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ KRISTIANSEN, Tomas (25 February 2013). "SeaIntel: 46 nye kæmpe containerskibe indsættes i 2013". ShippingWatch. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ "UK: DP World to Spend USD 2.5 Billion on London Deepwater Gateway". Dredging Today. 27 July 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ "[1]"

External links

[edit]- Making Waves: Maersk's website dedicated to the new family of ships

- Rendering of the Triple-E class

- Kremer, William. "How much bigger can container ships get?", BBC News, BBC. 19 February 2013.