Logan (novel)

Title page of the first edition, volume 1 | |

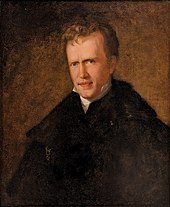

| Author | John Neal |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Gothic, historical |

| Set in | Colony of Virginia |

| Publisher | H. C. Carey & I. Lea |

Publication date | 1822 |

| Pages | 658 (first edition) |

| OCLC | 12207199 |

| LC Class | PZ3 .N2521 |

Logan, a Family History is a Gothic novel of historical fiction by American writer John Neal. Published anonymously in Baltimore in 1822, the book is loosely inspired by the true story of Mingo leader Logan the Orator, while weaving a highly fictionalized story of interactions between Anglo-American colonists and Indigenous peoples on the western frontier of colonial Virginia. Set just before the Revolutionary War, it depicts the genocide of Native Americans as the heart of the American story and follows a long cast of characters connected to each other in a complex web of overlapping love interests, family relations, rape, and (sometimes incestuous) sexual activity.

Logan was Neal's second novel, but his first notable success, attracting generally favorable reviews in both the US and UK. He wrote the story over a six-to-eight-week stretch at a time when he was producing more novels and juggling more responsibilities than any other period of his life. Likely a commercial failure for the publisher, who refused to work with Neal in the future, the book nevertheless saw three printings in the UK. Scholars criticize the story's profound excessiveness and incoherence, but praise its pioneering and successful experimentation with psychological horror, verisimilitude, sexual guilt in male characters, impacts of intergenerational violence, and documentation of interracial relationships and intersections between sex and violence on the American frontier.

These experimentations influenced later American writers and foreshadowed fiction by Nathaniel Hawthorne, Walt Whitman, Robert Montgomery Bird, and Edgar Allan Poe. The novel is considered important by scholars studying the roles of Gothic literature and Indigenous identities in fashioning an American national identity. It advanced the American literary nationalist goal of developing a new native literature by experimenting with natural diction, distinctly American characters, regional American colloquialism, and fiercely independent rhetoric. It is considered unique amongst contemporary fiction for the preponderance of sexually explicit content and gratuitous violence.

Plot[edit]

The story begins in the colony of Virginia in 1774. Mingo chief Logan enters the chamber of the governor of Virginia and overpowers him. The governor is saved by Harold, a young man of mixed English and Indigenous descent who lives among the Mingo. Harold impregnates the half-asleep governor's wife Elvira, who is infatuated with Logan and finds Harold similarly attractive.

The Virginia Governor's Council meets with Native Americans; Logan demands a treaty and decries the Yellow Creek massacre by white frontiersmen from Virginia. Suspicious of Logan's Indigenous identity, Mohawks realize he is actually an English aristocrat from Salisbury named George Clarence. They follow and attack him in the woods. Logan escapes, seriously injured.

The governor learns about Harold's sexual relationship with Elvira and banishes him to the woods. There he meets Logan and the two realize they are both in love with a Mingo woman named Loena. They threaten each other, then realize Logan is Harold's father. Logan dies after securing a promise from Harold that he will lead the Mingos to "pursue the whites to extermination, day and night, forever and ever".[1]

Harold arranges a funeral for Logan, though his body has disappeared. The funeral is attacked by Native Americans, who injure both Harold and Elvira. They reveal romantic feelings for each other, though Elvira is unconsciously attracted to Harold as a surrogate for her attraction to Logan. Harold decides to leave Virginia, but stays for Elvira. He visits her at night and the two have sex, leaving Harold racked with remorse, and running to Loena for consolation.

Harold leads the Mingo into battle against a combined force of Mohawks and British colonists. He is reunited with Loena and convinces her to join him on a trip to Europe to prepare himself for leadership of the Mingo tribe. They start by traveling to Quebec City, where Loena remains, parting with Harold on poor terms after she learns about his relationship with Elvira.

While sailing to Europe, Harold is haunted by his own thoughts of Loena and meets a child named Leopold, who grows attached to him. Harold also meets an intellectual genius named Oscar, who has long conversations with Harold, opining on capital punishment, religious freedom, American slavery, moral double standards, ancient societies, and Shakespeare. Harold witnesses him leaping overboard in a crazed fit over a former lover. Harold then learns that Elvira is on board, that Leopold is her son, and his as well. Harold was originally traveling to France, but decides to accompany her and Leopold to England, where he discovers his familial connections to British nobility.

Harold learns that his father left behind children in England and moved to North America to live a double life as Logan. Harold meets his sister Caroline and learns that Oscar was his brother and Loena is his sister. Oscar, Harold learns, was crazed by the belief that he murdered Elvira, who was once his lover. Leopold dies. Harold confesses to Elvira that he loves another woman and she confesses to him that she has loved him for his resemblance to Oscar.

Harold champions the cause of Native Americans before the British Parliament before he and Elvira return to North America. Just before they are married, Harold leaves Elvira for Loena, but learns that Loena is in love with Oscar, who did not die, but was rescued after jumping ship in the Atlantic. On a moonlit night, all four visit the spot where Harold met Logan and where the latter died. Harold is shot by a figure in the distance, who turns out to be Logan, who is still alive, but delirious. Upon learning that he has killed his son, Logan cries out, then is killed by Oscar, his other son. Loena kisses Harold's corpse and dies. Elvira confesses to Oscar her sexual history with Harold and Oscar goes mad, then dies. The narrator ends by asking English readers to "acknowledge us, as we are, the strongest (though boastful and arrogant) progeny of yourselves ... when your nation was a colossus".[2]

Themes[edit]

American Indians and US nationhood[edit]

John Neal wrote Logan as white American authors were beginning to look toward American Indians as a dominant source of inspiration.[3] Scholars have pointed to the way Logan can be understood as portraying Indians as the originators of American nationhood, with white Americans as the inheritors of that legacy.[4] Harold calling for America's Indigenous nations to unify against British colonization seemingly parallels calls by Anglo-Americans for revolution just a few years after the novel takes place.[5] The historical Logan was an Indigenous leader of the Mingo people, but the Logan of Logan is revealed to be an English aristocrat assuming an Indigenous identity, suggesting that such an identity can be assumed by one's will.[6] Once assumed, Indigenous identity can be used to differentiate white Americans from the British in a manner similar to that used by instigators of the Boston Tea Party or the Improved Order of Red Men.[7] This would place Patriot colonists as inheritors of Indigenous territory for the making of the new American nation.[8]

Scholars see Neal's blurring of racial boundaries in family relationships as a testament to humanity's commonality.[9] This interpretation is reinforced by the characters' habit of confusing identities: Elvira mistakes Harold for Oscar, Harold mistakes Elvira for Leona, and Harold and Oscar are fashioned as character doubles.[10] It was common in nineteenth-century literature to portray American Indians as vanishing to make way for a new American national identity. This novel's uncommonly excessive and incoherent narrative could be Neal's way of indicating the contradiction inherent in this portrayal.[4] In this view, Neal's national identity of the new United States is neither Indigenous nor white, but both.[11] Writing interracial relationships and sexual fantasies into a novel in 1822 was taboo, and this pioneering effort foreshadowed future works by Nathaniel Hawthorne and other American authors.[12]

Harold being of mixed ancestry, exploring both his Indigenous identity in America and his English roots overseas, may also be a tool for Neal to question the emerging concept of manifest destiny and to paint the US as a multinational, cosmopolitan nation with permeable boundaries.[13] Acknowledging the contradictory reality of racial separation in the US may be Neal's reason for ending the novel with disaster and death for all major characters: "a place of broken hearts, and shattered intellects", as he states in the novel.[14] The novel's Gothic depiction of the genocide of Native Americans as central to the American story[15] can be seen as an indictment of American imperialism.[16] Logan's lack of coherence and cohesiveness may reflect Neal's disdain for institutional structures generally and his belief that the US, like all nations, has a finite lifespan.[17] Alternatively, it may be that Neal meant for this mass death scene at the novel's conclusion to symbolize the American Revolution's function of renewing various colonial-era allegiances into a single American nation.[18]

Sexual guilt[edit]

When he was temporarily living with the family of his business partner in 1818, Neal snuck into the bedroom of that business partner's sister, and into her bed. She cried out and Neal returned to his room before her family came to her assistance. This event, alternately described by scholars as either a failed seduction or an attempted rape, was fictionalized in different forms in all of Neal's four novels published between 1822 and 1823.[19] The theme of sexual guilt running through all four novels is seen as Neal processing this personal trauma.[20] In Logan, this materialized as the dream-like and questionably-consensual sex scene between Harold and Elvira,[21] leaving the protagonist shrouded in intense sexual guilt, which he considers ending with suicide, but then channels into a war he leads against the Mohawk and British colonists.[22] This is one of multiple instances of male protagonists in Neal's novels committing sexual crimes and dealing with consequences that scholars Benjamin Lease and Hans-Joachim Lang claim "reflect a sophisticated awareness on Neal's part of male chauvinism in a male-dominated world".[23] The preponderance of complicated sexual activity and love triangles between related characters can also be interpreted as supporting the theme of American national disunity.[24] This explicitly sexual content, sometimes interracial, and exhibiting both men and women as sexually motivated, is unique for the period[25] and likely influenced Hawthorne's focus on sexual guilt in his fiction.[19]

Style[edit]

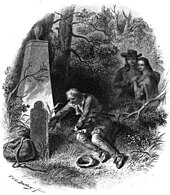

"Their blades met. Harold was the more wary, the more lightning-like, but the stranger was bolder, and stronger. Both were resolute as death. Several wounds were given, and received. Harold's sword broke to the hilt. He threw himself upon the stranger and bore him to the earth, wrenched his sword from him, and twice, in his blindness and wrath attempted, in vain, to pass it through and through his heart, as they grappled together. But twice the Englishman caught the sharp blade in his hands, and twice Harold withdrew it, by main force, through his clenched fingers, slowly severing sinew, and tendon, and flesh, and grating on the bones, as it passed. Harold gasped—the Englishman held him by the throat—the blood gushed from his ears and nostrils—once more!—he has succeeded! The blood has started through the pores of the brave fellow before him! His arteries are burst—He is dead—dead!—nailed to the earth, and Harold is sitting by him, blinded and sick.

A half hour has passed. The horse stamps, impatiently, by the corse [sic]. Why stands Harold thus, gazing upon the red ruin before him, with such deadly hatred?"

Example of gratuitous violence[26]

Like many of Neal's novels, Logan exhibits stylistic choices meant to advance American literary nationalism: natural diction, distinctly American characters, regional American colloquialism, and rhetoric of independence.[27] This is made explicit in the preface: "I hate prefaces. I hate dedications. Enough ... to say, that here is an American story".[28] This rejection of the preface's customary purpose can be read as a rejection of British literary convention that Neal sought in order to form a distinctly American literature.[29] Possibly to point out the absurdity of American novelists employing British Gothic conventions, he included those conventions only while the story had moved to England in the second volume.[30]

Logan represents Neal's effort to Americanize the Gothic style, otherwise associated with British literature, by rejecting British conventions and developing new ones based on America's history of racial persecution. In a nation bereft of ancient architecture, Neal uses natural landmarks as witnesses to colonial violence.[31] Neal was inspired by the "haunted elm" in Charles Brockden Brown's novel Edgar Huntly (1799) as a Gothic American natural landmark. Logan advanced the device by using a haunted tree visited by Harold that has stood witness to violence since long before recorded or oral histories, but most recently, that which has been committed by Anglo-American colonizers against Native Americans.[32] These Gothic devices foreshadowed future works by American authors: intermingling romance and violence in American border regions in Nick of the Woods (1837) by Robert Montgomery Bird; impacts of crimes by the father on the life of the son in multiple works by Hawthorne; and maniacal psychology in multiple works by Walt Whitman and Edgar Allan Poe, particularly Poe's The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym.[33]

Scholar Theresa A. Goddu refers to the novel as "Neal's wildest gothic experiment",[15] which relies heavily on gratuitous and incessant descriptions of violence:[34] scalping, murder, hatred, rape, and incest. This was unique for the period[25] and was matched neither by Brown, Neal's inspiration in this regard, or by Poe, his best-known immediate successor.[35] The novel's conclusion, according to scholar Lillie Deming Loshe, is "an epidemic of death and insanity".[36] This brand of Gothicism also relies on loose structure and unrestrained emotional intensity to the point of incoherence.[37] Neal avoided dialogue tags "said he" and "said she" whenever possible to heighten the sense of immediacy in characters' actions.[38] His repetitive statements at moments of emotional intensity are what scholar Jonathan Elmer refers to as "spastic iteration",[39] as in: "Yes, I saw him ... alone, alone! All, all alone!" and "Not dead!—no, no, not dead!—not dead!"[40] Neal used dashes of variable lengths, varying types of ellipses, and abundant parentheses, italics, and exclamations to excite and exhaust the reader.[41] Scholars have referred to these techniques as resulting in "off-putting disjointedness",[42] "melancholic Byronism",[39] and a "hyperkinetic and sometimes hyperbolic sense of energy".[43] In his 877-page study of American literature from the Revolutionary War through 1940, scholar Alexander Cowie found that only Bird's The Hawks of Hawk Hollow (1835) could compare with Logan's level of incoherence.[44] Neal himself warned readers: "It should be taken, as people take opium. A grain may exhilarate—more may stupify—much will be death."[45]

Background[edit]

Stylistically, Logan bears the influence of Wieland (1798) and Edgar Huntly (1799) by Charles Brockden Brown,[46] whom Neal saw as his literary father and one of only two American authors beside himself who by 1825 had successfully contributed toward developing a distinctively American literature.[47] However, Neal drew the novel's core concept from "Logan's Lament",[48] a speech delivered after the conclusion of Lord Dunmore's War by an American Indian figure referred to variably as Logan or Ta-gah-jute.[49] The speech was first published in 1775, but made famous by Notes on the State of Virginia by Thomas Jefferson in 1787. It was commonly known by Neal's childhood, but his attention may have been directed to it by the epic poem Logan, an Indian Tale (1821) by Samuel Webber (1797–1880).[50] Neal likely believed the speech to be genuine when he wrote the novel, though in 1826 he called its provenance into question, referring to it in The London Magazine as "altogether a humbug".[51]

Neal wrote Logan in Baltimore during the busiest part of his life between the bankruptcy of his dry goods business in 1816 and his departure for England in 1823.[52] He spent between six and eight weeks writing it, finishing on November 17, 1821.[53] By March 1822 he had written three more novels,[54] which he considered "a complete series; a course of experiment" in declamation (Logan), narrative (Seventy-Six), epistolary (Randolph), and colloquialism (Errata).[55] This was the most productive period of Neal's life as a novelist,[56] shortly after he passed the bar and began practicing law in 1820.[57] Whereas Keep Cool (1817) was his first serious attempt at producing literature, Logan was published after Neal had gained a considerable reputation as an author and critic,[58] and had worked for years on refining his theory of poetry to the point that he came to see the novel as the highest form of literature, able to communicate a poetic prose superior to formal poetry.[59]

Between the two novels, Neal labored for years reading law and supporting himself with other literary ventures: the epic poem Battle of Niagara (1818), the index to the first twelve volumes of Niles' Weekly Register (1818), the play Otho (1819), and the nonfiction History of the American Revolution (1819),[60] as well as serving as the editor and daily columnist for the daily newspaper Federal Republican and Baltimore Telegraph for about half of 1819.[61] Neal also actively advocated many reform issues at the time and used his novels to express his opinions.[62] In Logan, he supported the rights of American Indians and condemned debtors' prisons, slavery, and capital punishment.[63] His depiction of public executions in the novel may have factored into the national movement to remove them to private settings.[64] He also attacked lotteries in the novel, depicting them as mechanisms for robbing the poor.[65]

Neal published the novel anonymously, but hinted at his authorship in Blackwood's Magazine in 1825, saying he could neither "acknowledge or deny" the claim.[66] In his 1830 anonymously-published novel Authorship, the protagonist refers to Logan as the product of Carter Holmes, the pen name he used for Blackwood's.[67] Neal's anonymously-published novel Seventy-Six is credited to "the author of Logan".[68] When Logan was republished in 1840, it was credited to "the author of Seventy-Six".[69]

Publication history[edit]

In 1821, Neal approached well-known Philadelphia-based publishers Carey and Lea with the manuscript of Logan.[58] They delayed publication for months because of printing issues and their own reservations concerning the novel's profanity, "wildness", and "incoherence", which they claimed made the story "not well calculated for the novel readers of our day".[70] The first edition was released in two volumes in April 1822.[58] Published five years after Keep Cool, Logan was Neal's second novel, but his first of notable success.[71] It was pirated in London three times: under the original title by A. K. Newman and Company in 1823 and as Logan, the Mingo Chief. A Family History by J. Cunningham in 1840 and 1845.[72] It was Neal's first novel published outside the US and the only one ever published abroad more than once.[58] Despite the considerable influence it had on successive generations of American writers, Logan was never republished in the US.[73] Carey and Lea refused to publish anything else by Neal, likely because of the novel's poor sales.[74] Neal nevertheless enjoyed encouragement enough to continue his career as a novelist.[63]

Reception[edit]

Period critique[edit]

Logan received generally favorable criticism in both the US and UK, though British reviews were more often mixed in praising it as the work of a genius while criticizing it as erratic.[75] Philadelphia journalist Stephen Simpson issued ecstatic praise: "In all the productions of the human understanding, that we have ever heard of ... we remember nothing, we know of nothing, we can conceive of nothing equal to this romance."[76] Comparing to Neal's chief rival, James Fenimore Cooper,[77] Simpson expresses "astonishment that the still life of the Pioneers, should be read and applauded in the same age that produced Logan!"[76] A British journalist in The Literary Gazette made a similar comparison to Cooper, noting that Logan and Neal's subsequent novels Seventy-Six and Brother Jonathan are "three of about as extraordinary works as ever appeared—full of faults, but still full of power; if we except these, there is no rival near Mr. Cooper's throne."[78] The British Literary Chronicle and Weekly Review praised Neal's lifelike depiction of Indigenous dialogue and claimed that Logan "possesses considerable interest, and the work will be no discredit to the shelves of a modern circulating library".[79] The British Magazine of Foreign Literature claimed that the novel failed because of its rejection of established British literary conventions:[80]

It would be difficult, indeed, to guess what end he purposed to accomplish by his singular work. It could not be to amuse his readers, because it is intelligible; if he wished to frighten them he has failed of his end, for he only makes them laugh ... We laugh not with him, but at him. His style is the most singular that can be imagined—it is like the raving of a bedlamite. There are words in it, but no sense ... We have taken some pains to inquire who the author may be, but without success;—it is, perhaps, as well that we are in ignorance of his name; the knowledge must be painful, as we have no doubt that the poor gentleman is at this time suffering the wholesome restraint of a straw cell and a strait waistcoat. If he is not, there is no justice in America.[81]

Neal's self-criticism acknowledges the novel's fatal excesses.[82] The preface to Seventy-Six (1823) bemoans Logan's "rambling incoherency, passion, and extravagance" and expresses Neal's hope (writing anonymously) that he showed improvement with that novel.[83] His next (also anonymously-published) novel after that, Randolph (1823), includes this criticism of Logan from the protagonist: "Nobody can read it through, deliberately, as novels are to be read. You are fagged and fretted to death, long and long before you foresee the termination."[84] Two years after that, he wrote under an English pen name in the Scottish Blackwood's Magazine: "Logan is full of power–eloquence–poetry–instinct ... Yet so crowded—so incoherent— ... so outrageously overdone, that no-body can read it through. Parts are without parallel for passionate beauty;—power of language: deep tenderness, poetry—yet every page ... is rank with corruption—the terrible corruption of genius."[85] Writing under his own name in his autobiography almost a half century later, he called Logan "a wild, passionate, extravagant affair with some ... of the most eloquent and fervid writing I was ever guilty of, either in prose or poetry".[86]

Modern views[edit]

The majority of modern scholars agree that Logan is too incoherent to enjoy.[82] Cowie found the novel confusing for all of Neal's attempts at exuding high energy and emotion.[87] Biographer Irving T. Richards felt similarly about the novel's excessive Gothic features[88] and added that he considered the characters unrealistic: "They are swept by emotional waves over which they have no control and for which they are not accountable."[89] Scholar Fritz Fleischmann feels the novel is "oversized and excessive" and full of "lacerating thoughts [that] pass by the reader, often without much rhyme or reason."[90] Biographer Benjamin Lease dubs it "an incoherent failure" of "high pitched absurdity" with "scarcely a plot".[91] Authors of the Literary History of the United States claimed Neal must have been too busy with his law studies and other simultaneous literary pursuits to be original: "He snatched high-minded villains from Godwin and low-minded heroes from Byron, then sent them roaring and murdering through the hackneyed routines of cheap melodramas".[92] Literary historian Fred Lewis Pattee, who collected a series of Neal's literary criticism for publication in 1937, remarked on Neal's rapidity in drafting novels like Logan: "Two-volume novels thrown off in a month! Hard to believe—until one reads the novels."[93]

Scholars Edward Carlson and David J. Carlson nevertheless claim Logan to be one of Neal's four best novels.[43] Richards felt that its plot structure showed a clear improvement over Neal's first novel, Keep Cool,[94] with better use of characters, tone, structure, and suspense.[95] Cowie felt that there was particular strength in the novel's psychological horror that foreshadowed later works by Poe.[87] Arthur Hobson Quinn felt similarly, pointing to the fact that the publishers were challenged to prove that the novel was not a copy of the celebrated William Godwin, because Godwin's novel The Pirate was published just months prior.[96] Goddu went further to say that those Gothic elements surpassed anything by either Poe or Brown.[97] Also comparing to Neal's peers, scholar Philip F. Gura called the novel "remarkable" for documenting the historic reality of interracial relationships that contemporaries like Cooper avoided.[98] Fleischmann praised Logan's verisimilitude: "Spurning the adornments of past literary styles, it succeeds by spontaneity ..., by recreating the tumble of emotions present in real life."[99]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Neal 1822a, p. 110.

- ^ Neal 1822b, p. 340.

- ^ Goddu 1997, p. 57.

- ^ a b Goddu 1997, p. 63.

- ^ Pethers 2012, p. 9.

- ^ Nelson 1998, pp. 92–94.

- ^ Nelson 1998, p. 101.

- ^ Nelson 1998, pp. 88, 90.

- ^ Goddu 1997, pp. 60, 65.

- ^ Goddu 1997, p. 65.

- ^ Elmer 2006–2007, p. 167.

- ^ Gura 2013, pp. 43, 46.

- ^ Richter 2003, p. 246; Watts 2012, pp. 212–213; Goddu 1997, p. 66.

- ^ Richter 2003, p. 247, quoting Logan.

- ^ a b Goddu 1997, p. 53.

- ^ Welch 2021, p. 486.

- ^ Elmer 2006–2007, pp. 160–163.

- ^ Pethers 2012, p. 10.

- ^ a b Fleischmann 1983, p. 246.

- ^ Fleischmann 2012, p. 252.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 91.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 249.

- ^ Lease & Lang 1978, p. xvii.

- ^ Goddu 1997, p. 67.

- ^ a b Gura 2013, p. 44.

- ^ Neal 1822a, p. 216.

- ^ Pethers 2012, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Pethers 2012, p. 8, quoting Logan's preface.

- ^ Merlob 2012, p. 102.

- ^ Welch 2021, pp. 471–472.

- ^ Welch 2021, p. 484; Goddu 1997, pp. 53–55.

- ^ Sivils 2012, pp. 42–45.

- ^ Lease 1972, pp. 90–91; Sears 1978, p. 43.

- ^ Sivils 2012, p. 42; Goddu 1997, p. 64.

- ^ Goddu 1997, pp. 60, 72.

- ^ Loshe 1958, p. 93.

- ^ Goddu 1997, p. 59.

- ^ Martin 1959, p. 470.

- ^ a b Elmer 2006–2007, p. 154.

- ^ Elmer 2006–2007, p. 167, quoting Logan.

- ^ Goddu 1997, pp. 62, 66.

- ^ Welch 2021, p. 483.

- ^ a b Watts & Carlson 2012b, p. xxv.

- ^ Cowie 1948, p. 251.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 44, quoting Neal.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 90; Fleischmann 1983, p. 251; Sivils 2012, pp. 42–45.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, pp. 5–8.

- ^ Goddu 1997, p. 61.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 329–330; Goddu 1997, p. 60.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 327.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 329n4, quoting Neal.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 147.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 322–323.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 22.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 56, quoting Neal.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 34.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 90n1, 196–197.

- ^ a b c d Richards 1933, p. 323.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 39.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 40.

- ^ Sears 1978, pp. 146–147; Gallant 2012, p. 1.

- ^ Martin 1959, pp. 457–458.

- ^ a b Cowie 1948, p. 166.

- ^ Jackson 1907, p. 521.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 105.

- ^ Elmer 2012, p. 150, quoting Neal.

- ^ Richter 2012, p. 79.

- ^ Neal 1971, Title page.

- ^ Neal 1840, Title page.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 40, quoting letters from the publishers to Neal.

- ^ Nelson 1998, p. 90.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 323; Sears 1978, p. 133n14.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 44.

- ^ Goddu 1997, p. 175n12.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 324–325; Sears 1978, pp. 40, 44; Lease & Lang 1978, p. xiv.

- ^ a b Lease 1972, p. 41, quoting Stephen Simpson.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 39.

- ^ Cairns 1922, p. 150, quoting The Literary Gazette.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 325.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 324–325.

- ^ Cairns 1922, p. 208, quoting Magazine of Foreign Literature.

- ^ a b Goddu 1997, p. 62.

- ^ Goddu 1997, p. 61, quoting Seventy-Six.

- ^ Goddu 1997, pp. 174–175n11, quoting Randolph.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 44, quoting Blackwood's Magazine.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 40, quoting Neal's autobiography.

- ^ a b Cowie 1948, p. 168.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 347.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 340.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 251.

- ^ Lease 1972, pp. 86, 90, 106.

- ^ Spiller et al. 1963, p. 291.

- ^ Pattee 1937, p. 5.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 334–335.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 325–326.

- ^ Quinn 1964, p. 48.

- ^ Goddu 1997, p. 60.

- ^ Gura 2013, p. 43.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 242.

Sources[edit]

- Cairns, William B. (1922). British Criticisms of American Writings 1815–1833: A Contribution to the Study of Anglo-American Literary Relationships. University of Wisconsin Studies in Language and Literature Number 14. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin. OCLC 1833885.

- Cowie, Alexander (1948). The Rise of the American Novel. New York City, New York: American Book Company. OCLC 268679.

- DiMercurio, Catherine C., ed. (2018). Nineteenth-Century Literature Criticism: Criticism of the Works of Novelists, Philosophers, and Other Creative Writers Who Died between 1800 and 1899, from the First Published Critical Appraisals to Current Evaluations. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Gale, A Cengage Company. ISBN 9781410378514.

- Elmer, Jonathan (Fall 2006 – Spring 2007). "Melancholy, Race, and Sovereign Exemption in Early American Fiction". Novel: A Forum on Fiction. 40 (1/2): 151–170. doi:10.1215/ddnov.040010151. JSTOR 40267688.

- Elmer, Jonathan (2012). "John Neal and John Dunn Hunter". John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. pp. 145–157. In Watts & Carlson (2012a).

- Fleischmann, Fritz (1983). A Right View of the Subject: Feminism in the Works of Charles Brockden Brown and John Neal. Erlangen, Germany: Verlag Palm & Enke Erlangen. ISBN 9783789601477.

- Fleischmann, Fritz (2012). "Chapter 12: "A Right Manly Man" in 1843: John Neal on Women's Rights and the Problem of Male Feminism". John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. pp. 247–270. In Watts & Carlson (2012a).

- Gallant, Cliff (July 13, 2012). "The Churlish and Brilliant John Neal". The Portland Daily Sun. Portland, Maine. pp. 1, 5.

- Goddu, Theresa A. (1997). Gothic America: Narrative, History, and Nation. New York City, New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231108171.

- Gura, Philip F. (2013). Truth's Ragged Edge: The Rise of the American Novel. New York City, New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 9780809094455.

- Jackson, Charles E. (July 1907). "Maine Charitable Mechanic Association". Pine Tree Magazine. Vol. 7, no. 6. Portland, Maine: Sale Publishing Co. pp. 515–523.

- Lease, Benjamin (1972). That Wild Fellow John Neal and the American Literary Revolution. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226469690.

- Lease, Benjamin; Lang, Hans-Joachim, eds. (1978). The Genius of John Neal: Selections from His Writings. Las Vegas, Nevada: Peter Lang. ISBN 9783261023827.

- Loshe, Lillie Deming (1958) [1907]. The Early American Novel 1789–1830. New York City, New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co. OCLC 269646.

- Merlob, Maya (2012). "Celebrated Rubbish: John Neal and the Commercialization of Early American Romanticism". John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. pp. 99–122. In Watts & Carlson (2012a).

- Martin, Harold C. (December 1959). "The Colloquial Tradition in the Novel: John Neal". The New England Quarterly. 32 (4): 455–475. doi:10.2307/362501. JSTOR 362501.

- Neal, John (1822a). Logan, a Family History. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: H. C. Carey & I. Lea. OCLC 12207199.

- Neal, John (1822b). Logan, a Family History. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: H. C. Carey & I. Lea. OCLC 12207199.

- Neal, John (1840). Logan, the Mingo Chief. A Family History. London, England: J. Cunningham. OCLC 11243702.

- Neal, John (1971). Seventy-Six. Bainbridge, New York: York Mail–Print, Inc. OCLC 40318310. Facsimile reproduction of 1823 Baltimore edition, two volumes in one.

- Nelson, Dana D. (1998). National Manhood: Capitalist Citizenship and the Imagined Fraternity of White Men. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822321491.

- Pattee, Fred Lewis, ed. (1937). American Writers: A Series of Papers Contributed to Blackwood's Magazine (1824–1825). Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. OCLC 464953146.

- Pethers, Matthew (2012). "'I Must Resemble Nobody': John Neal, Genre, and the Making of American Literary Nationalism". John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. pp. 1–38. In Watts & Carlson (2012a).

- Quinn, Arthur Hobson (1964) [1936]. American Fiction: An Historical and Critical Survey (Students' ed.). New York City, New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc. OCLC 610879015.

- Richards, Irving T. (1933). The Life and Works of John Neal (PhD). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University. OCLC 7588473.

- Richter, Jörg Thomas (2003) [Originally published in Colonial Encounters: Essays in Early American History and Culture. Heidelberg, Germany: Universitätsverlag Winter. pp. 157–172]. "Exemplary American: Logan, the Mingo Chief, in Jefferson, Neal, and Doddridge". Nineteenth-Century Literature Criticism: Criticism of the Works of Novelists, Philosophers, and Other Creative Writers Who Died between 1800 and 1899, from the First Published Critical Appraisals to Current Evaluations. pp. 241–249. In DiMercurio (2018).

- Richter, Jörg Thomas (2012). "Notes on Poetic Push-Pin and the Writing of Life in John Neal's Authorship". John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. pp. 75–97. In Watts & Carlson (2012a).

- Sears, Donald A. (1978). John Neal. Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 9780805772302.

- Sivils, Matthew Wynn (2012). "Chapter 2: "The Herbage of Death": Haunted Environments in John Neal and James Fenimore Cooper". John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. pp. 39–56. In Watts & Carlson (2012a).

- Spiller, Robert E.; Thorp, Willard; Johnson, Thomas H.; Canby, Henry Seidel; Ludwig, Richard M., eds. (1963). The Literary History of the United States: History (3rd ed.). London, England: The Macmillan Company. OCLC 269181.

- Watts, Edward (2012). "He Could Not Believe that Butchering Red Men Was Serving Our Maker: 'David Whicher' and the Indian Hater Tradition". John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. pp. 209–226. In Watts & Carlson (2012a).

- Watts, Edward; Carlson, David J., eds. (2012a). John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. Lewisburg, Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press. ISBN 9781611484205.

- Watts, Edward; Carlson, David J. (2012b). "Introduction". John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. pp. xi–xxxiv. In Watts & Carlson (2012a).

- Welch, Ellen Bufford (2021). "Literary Nationalism and the Renunciation of the British Gothic Tradition in the Novels of John Neal". Early American Literature. 56 (2): 471–497. doi:10.1353/eal.2021.0039. S2CID 243142175.

External links[edit]

- Logan, a Family History 1822 Philadelphia edition at the Internet Archive

- Logan, a Family History 1822 Philadelphia edition available at Hathitrust

- Logan, a Family History 1823 London edition available at Google Books in four volumes: volume 1, volume 2, volume 3, volume 4

- Logan, the Mingo Chief. A Family History 1840 London edition available at Hathitrust