Jeremy Deller

Jeremy Deller | |

|---|---|

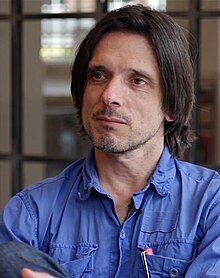

Deller in 2015 | |

| Born | 30 March 1966 London, England, UK |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | University of Sussex |

| Known for | Conceptual art, 'Social Surrealism' |

| Notable work | Acid Brass, Battle of Orgreave, Sacrilege |

| Movement | Post-YBAs |

| Awards | Turner Prize Albert Medal (2010) |

| Website | www |

Jeremy Deller (born 30 March 1966)[1] is an English conceptual, video and installation artist. Much of Deller's work is collaborative; it has a strong political aspect, in the subjects dealt with and also the devaluation of artistic ego through the involvement of other people in the creative process. He won the Turner Prize in 2004 and represented Great Britain at the Venice Biennale in 2013.[2][3]

Early life and education

[edit]Jeremy Deller was born in London and educated at St John's and St Clement's Primary School and Dulwich College before studying for his BA History of Art at Courtauld Institute of Art (University of London); he achieved his MA in Art History at the University of Sussex under David Alan Mellor.[4]

Work

[edit]

Deller traces his broad interests in art and culture, in part, to childhood visits to museums like the Horniman Museum, in South London. After meeting Andy Warhol in 1986, Deller spent two weeks at The Factory in New York. He began making artworks in the early 1990s, often showing them outside of conventional galleries. In 1993, while his parents were on holiday (he was 27, still living at home),[5] he secretly used the family home for an exhibition titled Open Bedroom.[6]

In 1997, Deller embarked on Acid Brass, a musical collaboration with the Williams Fairey Brass Band from Stockport. The project was based on fusing the music of a traditional brass band with acid house and Detroit techno.

Much of Deller's work is collaborative. His work has a strong political aspect, in the subjects dealt with and also the devaluation of artistic ego through the involvement of other people in the creative process. Folk Archive is a tour of "people's art" and has been exhibited throughout the UK including at Barbican Centre and most recently (2013) at The Public, West Bromwich, outside of the contemporary art institution. Much of his work is ephemeral in nature and avoids commodification.

Deller staged The Battle of Orgreave in 2001, bringing together almost 1,000 people in a public re-enactment of a violent confrontation from the 1984 Miners' Strike.[6][7] The re-enactment was filmed by director Mike Figgis for Artangel Media and Channel 4.[8] The Battle of Orgreave was ranked second in The Guardian's Best Art of the 21st Century list, with critic Hettie Judah calling it a "monument of sorts, the performance was at once participatory ritual, spectacle, living archive and a space to mourn".[9] In 2004, for the opening of Manifesta 5, the roving European Biennial of Contemporary art, Deller organised a Social Parade through the streets of the city of Donostia-San Sebastian, drafting in cadres of local alternative societies and support groups to participate.[10]

In 2005/6, he was involved in a touring exhibit of contemporary British folk art, in collaboration with Alan Kane. In late 2006, he instigated The Bat House Project, an architectural competition open to the public for a bat house on the outskirts of London.

The following year, 'Our Hobby is Depeche Mode', a documentary co-directed with Nick Abrahams about Depeche Mode fans around the world was premiered at the London Film Festival, and followed by festival screenings around the world.

In 2009, Deller created Procession,[11] a free and uniquely Mancunian parade through the centre of Manchester along Deansgate, a co-commission by Manchester International Festival and Cornerhouse. Procession worked with diverse groups of people drawn from the 10 boroughs of Greater Manchester and took place on Sunday 5 July at 1400 hrs.

Commissioned in 2009 as part of The Three M Project (a group composed of the New Museum, New York; the Hammer Museum, LA; and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, to exhibit and commission new works of art), Deller created It Is What It Is'.[12] The project was designed to foster public discussion by having guest experts engage museum visitors in a free-form, unscripted dialogue about issues concerning Iraq.[13]

In 2015 the exhibition The Infinitely Variable Ideal of the Popular was presented at MUAC in Mexico City, curated by Ferran Barenblit, Amanda de la Garza and Cuauhtémoc Medina. The exhibition traveled to Fundación Proa in Buenos Aires[14] and Alhóndiga in Bilbao.[15]

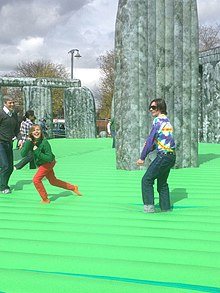

Sacrilege, a 1:1 bouncy replica of Stonehenge created for the 2012 Olympic Games was toured around the UK and eventually to Móstoles, Community of Madrid, in 2015. Charlotte Higgins, of The Guardian, noted that a megalithic bouncy by artist Jim Ricks had toured Ireland a few years previously, and wrote: "Why, after several millennia of human creativity, have two inflatable megalithic monuments come along at once?"[16] Despite claims of plagiarism, the two works were shown together in Belfast in the summer of 2012.[17][16]

On 1 July 2016, his We're Here Because We're Here, commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Battle of the Somme, took place in public spaces across the United Kingdom.[18] On 29 June 2017, his event "What Is The City But The People?" opened the Manchester International Festival.

In 2019 the Jewish Museum London commissioned Deller to create a short film of antisemitic footage showing contemporary media, politicians, and propagandists making antisemitic statements for its special exhibit Jews, Money, Myth.[19] Douglas Murray called the film's use of clips of U.S. President Donald Trump criticizing 'elites' for draining power from America "an unfair overclaim."[20]

Deller produced the documentary Everybody in The Place: An Incomplete History of Britain 1984–1992[21] which covered acid house and rave culture, and political turmoil in Britain in the 1980s and early-1990s, first shown by BBC Four on 2 August 2019.[22]

Later the same year, Deller was forced to admit that his design for the memorial to the Peterloo Massacre, intended to provide a podium for speakers and a monument to equality campaigners, had completely failed to make any provision for wheelchair users, despite corporate artwork prominently featuring wheelchair users and even though access had been raised during the consultation process. Protests by disabled groups led to a last minute redesign and Deller describing himself as "chastened".[23][24]

In June 2024, Deller brought Acid Brass to the streets of Melbourne, as part of the 2024 RISING: festival, with local brass bands including Merri-bek City Band, Glenferrie Brass, Victorian State Youth Brass Band, Dandenong Band, and Western Brass. [25]

Other roles

[edit]In 2007, Deller was appointed a Trustee of the Tate Gallery.[26][27] Between 2012 and 2013, he served on the board of trustees of the Foundling Museum.[28]

In December 2020 Deller was part of the winning team from the Courtauld Institute of Art in Christmas University Challenge.[29]

Awards and recognition

[edit]Deller was the winner of the Turner Prize in 2004.[2] His show at Tate Britain included documentation on Battle of Orgreave and an installation Memory Bucket (2003), a documentary about Crawford, Texas—the hometown of George W. Bush—and the siege in nearby Waco.

In 2010, he was awarded the Albert Medal of the Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures & Commerce (RSA) for 'creating art that encourages public responses and creativity'.[30]

The Battle of Orgreave ranked second in The Guardian's list of the best art of the 21st century.[31]

Political views

[edit]On 1 October 2010, in an open letter to the British Government's culture secretary Jeremy Hunt, co-signed by 28 former Turner prize nominees, and 18 winners, Deller opposed any future cuts in public funding for the arts. In the letter the co-signatories described the arts in Britain as a "remarkable and fertile landscape of culture and creativity".[32]

In August 2014, Deller was one of 200 public figures who were signatories to a letter to The Guardian opposing Scottish independence in the run-up to September's referendum on that issue.[33]

During the 2017 general election campaign he created a poster bearing the words "Strong and stable my arse", referring to Theresa May's election slogan, copies of which were publicly posted around London.[34]

Exhibitions

[edit]

Solo exhibitions

[edit]- Unconvention, Centre for Visual Arts, Cardiff, 1999

- After the Goldrush, Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco, 2002

- Folk Archive: contemporary popular art from the UK with Alan Kane, Centre Pompidou, Paris and Barbican Art Gallery, London, 2005

- Jeremy Deller, Kunstverein, Munich, 2005

- From One Revolution to Another, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2008

- It Is What It Is: Conversations About Iraq, Creative Time and New Museum, New York, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, and Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, 2009

- Procession, Cornerhouse, Manchester, 2009

- Joy in People, a retrospective, Hayward Gallery, London, February–May 2012.[35]

- Art is Magic, a retrospective, Rennes Museum of Fine Arts, Rennes; La Criée contemporary art center; Frac Bretagne Fonds régional d'art contemporain, France, 2023[36]

Other exhibitions

[edit]- EASTinternational, selected by Marian Goodman and Giuseppe Penone, 1995

- EASTinternational, 2006 with Dirk Snauwaert[37]

Deller was selected to represent Great Britain at the Venice Biennale in 2013.[3]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ "Jeremy DELLER - Personal Appointments (free information from Companies House)". find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk.

- ^ a b Jeremy Deller wins 2004 Turner prize The Guardian, 6 December 2004.

- ^ a b "Jeremy Deller shows a 'wistfully aggressive' Britain at Venice Biennale". the Guardian. 28 May 2013.

- ^ Chris Arnot, "David Alan Mellor: Image Maker", The Guardian, 1 March 2005. Accessed 22 October 2010.

- ^ Charlotte Higgins (6 December 2011), Jeremy Deller, Turner prizewinner, to have Hayward Gallery retrospective The Guardian.

- ^ a b Jeremy Deller: Joy in People, 22 February – 13 May 2012 Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine Hayward Gallery, London.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (18 June 2001). "Missiles fly, truncheons swing, police chase miners as cars burn. It's all very exciting. But why is it art?". The Guardian.

- ^ "The Battle of Orgreave". Artangel.org.uk. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ Searle, Adrian; Jones, Jonathan; O'Hagan, Sean; Judah, Hettie (17 September 2019). "The best art of the 21st century". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ "Frieze Magazine | Archive | MANIFESTA 5 European Biennial of Contemporary Art". Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- ^ Hickling, Alfred (5 July 2009). "Procession: Cornerhouse, Manchester". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ "It Is What It Is: Conversations About Iraq, A Project by Jeremy Deller" (PDF). Press Release. The New Museum and Creative Time for the Three M Project. 19 December 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ Laura Hoptman; Amy Mackie; Nato Thompson. "Project Description". The New Museum and Creative Time for the Three M Project. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ "Jeremy Deller - Exhibitions - Fundación Proa". proa.org. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ Bilbao, Azkuna Zentroa-Alhóndiga (22 June 2016), 2016-06-21 Jeremy Deller-10, retrieved 9 November 2022

- ^ a b Higgins, Charlotte (2 May 2012). "Glaswegian shoes come off for bouncy Stonehenge". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ Murphy, Liz (18 May 2012). "Karla, Jeremy and Margaret (my Mum)". A-N Magazine. #90, June 2012: 30 – via Issuu.

- ^ Higgins, Charlotte (1 July 2016). "#Wearehere: Somme tribute revealed as Jeremy Deller work". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ Neyeri, Farah (20 March 2019). "Get Updates Advertisement A Museum Tackles Myths About Jews and Money". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ Murray, Douglas (6 April 2019). "Is now a good time to talk about Jews and money?". The Spectator. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ IMDB https://www.imdb.com/title/tt10370776/

- ^ Mugs, Joe. ”Jeremy Deller on raving: 'Stormzy and Dave give me hope'”. The Guardian, 9 August 2019

- ^ "Peterloo memorial rethink amid disability access anger". BBC News. 14 March 2019.

- ^ "Protests force council climbdown over inaccessible Peterloo memorial". Disability News Service. 11 July 2019.

- ^ https://2024.rising.melbourne/program/acid-brass, Retrieved 2024-06-15.

- ^ "Jeremy Deller Appointed Tate Trustee", Tate, 10 January 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2008.

- ^ Sarah Thornton (2 November 2009). Seven Days in the Art World. New York. ISBN 9780393337129. OCLC 489232834.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Martin Bailey (30 September 2013), Art collection at stake in row between museum and charity Archived 3 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine The Art Newspaper.

- ^ "University Challenge - Christmas 2020: 3. Courtauld v Goldsmiths" – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "RSA Medals". RSA. Archived from the original on 5 January 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ Searle, Adrian; Jones, Jonathan; O’Hagan, Sean; Judah, Hettie (17 September 2019). "The best art of the 21st century". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ Peter Walker, "Turner prize winners lead protest against arts cutbacks," The Guardian, 1 October 2010.

- ^ "Celebrities' open letter to Scotland – full text and list of signatories". theguardian. 7 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ Brown, Mark (22 May 2017). "Jeremy Deller behind 'strong and stable my arse' posters in London". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ^ Brazil, Kevin. "Review of Joy in People". The Oxonian Review. Archived from the original on 9 June 2012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Exporama à Rennes. Art is magic, une rétrospective de Jeremy Deller cet été". Ouest France. 9 May 2023.

- ^ "David Barrett, Art Monthly, Issue 299, Sep 2006". Archived from the original on 23 October 2007.

External links

[edit]- Jeremy Deller – official site

- Bat House Project – main site

- Jeremy Deller, Turner Prize 2004, at Tate Gallery

- Watch The Battle of Orgreave, FourDocs, at Channel 4