J. Howard Crocker

J. Howard Crocker | |

|---|---|

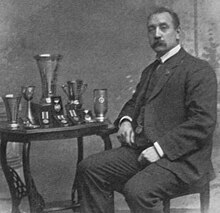

Crocker, c. 1908 | |

| Born | John Howard Crocker April 19, 1870 St. Stephen, New Brunswick, Canada |

| Died | November 27, 1959 (aged 89) Victoria, British Columbia, Canada |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | |

| Honours | LL.D. (Hon), M.P.Ed (Hon), Canadian Olympic Hall of Fame, New Brunswick Sports Hall of Fame |

John Howard Crocker (April 19, 1870 – November 27, 1959) was a Canadian educator and sports executive. He began teaching physical education at the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) in his hometown of St. Stephen, New Brunswick, then graduated from the International YMCA Training School, and introduced basketball to Nova Scotia at Amherst. He won the 1896 and 1897 Canadian pentathlon championships, then graduated from University of New Brunswick. After serving in Halifax, he was the physical education director for the Toronto Central YMCA, where he established the YMCA Athletic League. He introduced lifesaving courses to the curriculum by 1903, and was a charter member of the Ontario branch of the Royal Life Saving Society Canada in 1908. As the general secretary of the Brantford YMCA, he helped design and raise funds for a larger building to meet growing membership. He served the YMCA in China from 1911 to 1917, oversaw construction of a new building in Shanghai, and the city's first major sports stadium. He introduced volleyball to China in 1912, then helped establish the Far Eastern Championship Games in 1913. He later served as secretary of the Chinese Olympic Committee, and led a national physical education program with support of the Chinese government. Based in Winnipeg, he implemented YMCA programs despite World War I austerity measures. As secretary for physical education in Canada from 1921 to 1930, his physical education programs sought to produce a whole man, rather than an athlete. He retired from the YMCA after serving as president of the North American Physical Education Society from 1928 to 1930, remaining a lifetime advisor to the YMCA.

Crocker became involved in the Amateur Athletic Union of Canada (AAU of C) via his YMCA work, and was the Canadian representative on the International Basketball Rules Commission from 1905 to 1947. He was the manager of Canada at the 1908 Summer Olympics, the first organized national team for the Olympics. During his AAU of C tenure, he stood for amateur ideals, sought for youth to be educated to play sport for fun, and for athletes to represent Canada without financial gain. He updated the AAU of C constitution by replacing the board of governors with an elected executive committee, then served as president from 1932 to 1934. He led committees which evolved the definition of an amateur over time, allowing paid recreational sports directors and physical education directors. He also helped establish the Southwestern Ontario branch of the AAU of C, to give more cities a voice in organizing amateur sports. Crocker served as secretary of the Canadian Olympic Committee for 21 years, was chairman of selecting track and field athletes for Canada at the 1924 Summer Olympics, and was a boxing judge at the 1928 Summer Olympics. He sought for Canada to host international sporting events, and collaborated with Melville Marks Robinson to establish the British Empire Games in 1930. Crocker served on the British Empire Games Association of Canada for life, and managed Canada's track and field team at the 1938 British Empire Games. When the Canadian Olympic Association replaced the Canadian Olympic Committee by 1952, Crocker assisted in the transition and served as a lifetime advisor.

At the University of Western Ontario, Crocker was director of the physical education department from 1930 to 1947, where he established a Bachelor of Arts degree program in physical education, to produce teachers at secondary schools and instructors at recreational institutes. He was involved in student affairs and intramural sports, where he helped design a campus field house and raised funds for its construction. During his tenure, he kept the Western Mustangs football team operational during World War II with exhibition games versus the Ontario Rugby Football Union, and the university sponsored its first Canadian Interuniversity Athletics Union ice hockey team. In retirement, Crocker served as president of the Philatelic Society of London, Ontario, and was curator of the university's A. O. Jeffery Stamp Collection. For Crocker's work in China, he received an honorary Master of Physical Education degree from the International YMCA College in 1916. For his work in physical education, he received an honorary Doctor of Law degree from the University of Western Ontario in 1950. Other honours include becoming a lifetime governor of the Royal Life Saving Society Canada in 1938, and lifetime memberships from the YMCA and the Royal Philatelic Society of Canada in 1951. He was posthumously inducted into the builder categories of the Canadian Olympic Hall of Fame in 1960, and the New Brunswick Sports Hall of Fame in 2023.

Early life[edit]

John Howard Crocker was born in St. Stephen, New Brunswick, on April 19, 1870.[1][2] He was the eldest of five children to lumberman William Crocker and Mary Jane Dorcas, in a family of United Empire Loyalists residing in New Brunswick since 1810.[2] The family was a member of the Presbyterian Church in Canada.[3]

Crocker left school after eighth grade to help support the family, holding several jobs before working full-time in a drug store. At age 16, he began working in local logging camps.[2] His work in logging ended after falling into a river, when he caught a cold and then had rheumatic fever. While disabled for two years with a heart murmur and crutches, he completed secondary school while reading books and caring for bed-ridden persons.[4]

After schooling, Crocker apprenticed as a blacksmith and a machinist, and maintained industrial equipment for the Ganong candy company in St. Stephen.[5] As a blacksmith, Crocker learned to shoe horses, and attended local horse racing events. The physical work improved his strength, then he participated in lacrosse and football,[6] and served on the local volunteer fire department.[7]

When his father died in 1889, Crocker wanted to become a doctor.[8]

YMCA career[edit]

Education and early years[edit]

Crocker was introduced to the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) by his friend Lyman Archibald, who was general secretary of the YMCA in St. Stephen. Archibald helped Crocker build his physique by a routine including exercise and gymnastics, and competing at track and field events. As Crocker became proficient at the events, he helped demonstrate to other athletes.[9] He was elected to the physical education committee of the in 1891, and became chairman of the committee in 1892.[10] He organized annual Victoria Day track and field meets at the local horse racing track, and won most of the events himself.[8][11]

Crocker attended the International YMCA Training School in Springfield, Massachusetts, prior to beginning full-time YMCA work.[12] He was a student of James Naismith, the inventor of basketball.[13][14] In 1894, Crocker transferred to the YMCA in Amherst, Nova Scotia, as the secretary and physical education director.[1][15] In Amherst, he established a basketball program,[13][16] introducing basketball to Nova Scotia after the game appeared at the Montreal YMCA in 1892.[16]

Admitted to the University of New Brunswick in 1894, Crocker graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1898.[17][18] During this time, he participated in multiple events at the Maritime Athletic Association championships,[19] and competing in the pole vault using a homemade pole.[12]

Crocker won the 1896 and 1897 Canadian championship in the pentathlon, competing in the 100 metres sprint, mile run, high jump, pole vault, and hammer throw.[20][21] His personal best results in the pentathlon were a total score of 481 points; 10.5 seconds in the 100 metres sprint, 11 feet 2 inches (3.40 m) in the pole vault, 5 feet 2.5 inches (1.588 m) in the high jump, 21 feet 10.5 inches (6.668 m) in the long jump, 4 minutes 48 seconds in the mile run, and 2 minutes 2 seconds in the half-mile run.[22]

In 1898, Crocker began attending Dalhousie Medical School.[18] He played halfback on the Dalhousie Tigers men's soccer team, worked as a server at a local pub, and served as a physical education instructor at the YMCA in Halifax, Nova Scotia.[23][24] He directed summer boys' camps in Nova Scotia during 1898 and 1899, including a stay at Big Cove YMCA Camp.[25] He abandoned medical studies at Dalhousie in 1899, due to vision problems.[23][24]

Toronto Central physical education director[edit]

Late in 1899, Crocker accepted the full-time position of physical education director for the Toronto Central YMCA.[24][26][27] He instituted the practice of gymnasium uniforms, and a physical examination for participants to track their health and progress. He arranged for annual indoor athletics competitions between local YMCA branches, and oversaw recreational programs for baseball, basketball, fencing, gymnastics, lacrosse, rugby football, swimming and lifesaving, track and field, and wrestling.[28]

In 1901, Crocker established a YMCA Leaders' Club to physically and mentally challenge talented athletes. The framework for this program set the standards for what became the National YMCA Leaders' Corps. Among the 18 members of Crocker's inaugural Leaders' Club included Olympic racewalker Donald Linden.[29] Crocker later operated summer camps for the Leaders' Club on Lake Scugog and Lake Couchiching.[30] Crocker began conducting annual seminars for physical education directors in 1901, to raise the standards of instruction in Ontario. He directed classes in track and field, lifesaving, swimming, and gymnasium routines. By 1905, the courses were combined into YMCA summer camps operated by Crocker at Geneva Park on Lake Couchiching.[31]

In 1901, Crocker selected an all-Ontario basketball team to represent the province at the Sportsmen's Congress annual meeting in Chicago.[32] He promoted growth of basketball in Canadian newspapers, published expert notes on playing basketball, and stressed the need for clean play and skills practice.[33] In 1905, he represented the Toronto Central YMCA team in the newly formed senior division of the Canadian Basketball League.[34]

Crocker led efforts to establish the YMCA Athletic League in 1904, which organized and promoted sport between YMCA associations. He was named secretary-treasurer of the YMCA Athletic League in 1905, which affiliated with the YMCA Athletic League of the United States.[35] He subsequently wrote the Official handbook of the Athletic League of the Young Men's Christian Associations of Canada.[36]

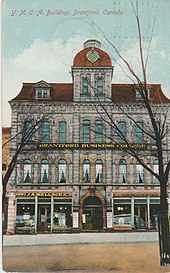

Brantford general secretary[edit]

Crocker began working as the general secretary of the Brantford YMCA in December 1908,[37][38] following a brief period in the real estate business.[39] Crocker oversaw renovations to the pool at Wycliffe Hall, then conducted swimming lessons for members and the public.[38][40] He also established first aid courses for the YMCA,[41] and instructed classes in basketball, calisthenics, and gymnastics.[40]

In team sports, Crocker coached basketball in YMCA intercity competitions,[42] in addition to refereeing some games.[43] He was a course clerk for athletics events,[44] and arranged the 1910 YMCA national athletics championships hosted in Brantford.[45] In 1910, he was elected president of the newly organized Brantford YMCA swimming club, to arrange water polo teams and games,[46] and was a judge for swimming competitions.[47]

The Brantford YMCA organized a junior ice hockey league including five teams for the 1908–09 season, with Crocker elected as vice-president.[48] For the 1909 season, he was elected president of the Brantford Junior Baseball League, which included a team from the YMCA and set an age limit of 19.[49][50]

In the annual racewalking event sponsored by the Brantford Expositor, Crocker fired the starting pistol, served a course judge, and was an expert on the Olympic rules for the event.[51][52] He was also involved in local sports as an on-field official for athletics events,[53] as a starter and timekeeper for bicycle races,[54] and the Brantford-to-Hamilton marathon race.[55]

Crocker regularly led bible study classes at the YMCA and local churches,[56] and was a guest speaker at churches, on the subject of brotherhood.[57] He conducted services at Sydenham Street Church in absence of its pastor,[58] and when the Reverend Maxwell was absent due to illness, Crocker filled in at the pulpit with an address on "The Vision of Jesus Christ".[59]

Membership in the Brantford YMCA grew from 100 people when Crocker began, to 800 by 1912. To replace the aging Wycliffe Hall opened in 1873, Crocker helped design a larger building, and led fundraising efforts for a new building completed in 1912.[38][60][61] The new facility included a gymnasium, swimming pool, bowling alley, billiard room, reading room, classrooms, and dormitories for 100 residents.[60]

During Crocker's tenure in Brantford, he declined the positions of secretary of the Montreal YMCA, and physical director of the Detroit YMCA and the Kansas City YMCA. When the International YMCA Committee requested that Brantford release Crocker that he could be reassigned to work in China, he initially declined due to work in progress on the new Brantford YMCA building.[22] In May 1911, directors of the Brantford YMCA agreed to release Crocker at the request of the International YMCA committee, who felt he was best suited for the YMCA mission in China. Crocker departed for his new position on June 27, 1911, after being given a banquet in his honour.[39]

China physical education and athletics[edit]

Crocker's travel to China included stops in Vancouver and San Francisco, then sailing via Hawaii and Japan, before his arrival on September 30, 1911.[62] He served as the foreign work secretary to promote physical education based in Shanghai, the headquarters of all YMCA work in China.[22][63] When he first arrived in China, the YMCA had facilities in large cities, but lacked a nationally co-ordinated effort.[38] He also organized the English-speaking population, and oversaw construction of a new building for the 1,200 YMCA members in Shanghai.[22][64] He also led efforts for construction of Shanghai's first major sports stadium.[20][21]

The beginning of Crocker's tenure in Shanghai coincided with the 1911 Revolution, in which rebels captured multiple cities in China but posed no danger to foreigners.[65][66] Crocker wrote that it was impossible to establish new operations due to the revolution, and that he was concerned for the physical and mental health of young men in China.[62]

Crocker initially taught physical education classes,[66] then oversaw first aid courses, and arranged an intercollegiate athletic meet.[67] In 1911, he arranged the first school for physical education directors in China. Later in the same year, he was named national secretary of physical education in China, when the YMCA erected new buildings in Canton, Fuzhou, Hankou, Beijing, and Tianjin.[68]

In 1912, the YMCA erected a new building and sporting field in Nanjing. Crocker aimed to construct separate buildings each for the English-speaking men, the Chinese boys, and national committee offices.[69] As of 1912, Crocker focused on conducting gymnasium classes, and introducing volleyball to schools and YMCA locations in China.[a]

International sports[edit]

Crocker aspired to send athletes to represent China at the 1912 Summer Olympics, but abandoned hopes due to the political changes following the 1911 Revolution.[69] He instead collaborated with Elwood Brown and from missionaries in China, Japan and the Philippines, to establish the Far Eastern Championship Games in 1913, becoming the secretary for the biannual international sporting event operating on a smaller scale than the Olympics.[71] Canadian missionary Reverend Gordon R. Jones, credited Crocker as the driving force behind establishment of the Far Eastern Games, due to visits to Japan, Hong Kong and the Philippines to organize the event.[72] Crocker used the "The Joy of Effort" as a logo, a work by Canadian educator and athlete R. Tait McKenzie.[73]

Crocker served as secretary of the Chinese Olympic Committee c. 1913 – c. 1916,[74] and was named manager of the Republic of China team at the 1915 Far Eastern Championship Games.[1][27] He was credited by the Brantford Expositor for building sport in China, such that the national team would have been well represented at the 1916 Summer Olympics had the event not been cancelled.[75]

Growth of physical education[edit]

The Far Eastern games raised national interest in sports, and led to support by the Chinese government for physical education training.[38] With the support of president Yuan Shikai, Crocker toured China to conduct training courses and establish a school for physical education instructors, and a teacher's training institute in Nanjing.[38][76] Crocker co-operated with the government's effort to organize student athletics at universities and colleges,[23] and felt that Yuan Shikai was "friendly to foreigners and courteous to the YMCA", while financially supporting the association's work.[77]

During October 1915, Crocker went on a city-wide speaking campaign at schools in Tianjin to promote physical education, and advocated for women to receive equal education. The support he received led to similar lectures in Baodingfu. The governor of Amoy asked Crocker to develop interest in athletics, where he spoke at all schools and colleges in the city, and arranged interschool athletics events. When he urged local businessmen for funding to construct playgrounds and employ an athletic director, money was pledged immediately. In Jiangsu, he and YMCA colleagues conducted courses to educate more physical education instructors. He published athletic literature in English and Chinese, including manuals for volleyball, indoor baseball, tennis, soccer, track and field; and manuals on how to set-up a sports governing body.[78]

Due to increasing demands for physical education, Crocker noted that the YMCA needed more general secretaries to manage training for the required teachers. Expansion plans into Tianjin and Canton were combined with construction of training schools for secretaries and physical education teachers.[77] He reported difficulty in finding men willing to go to China to teach. Crocker described his evolving YMCA role as an advisor to development, since native Chinese teachers and management had joined the YMCA.[79] He felt that the YMCA's future in China depended on securing and training men for the work, and Shanghai subsequently became the first training centre for physical education directors in China.[68]

Final years and return to Canada[edit]

Crocker returned to Canada in April 1916.[80] He took a leave of absence from his work to spend the summer in Canada, to study and accumulate resources for further of training physical education directors, and attend YMCA conferences in Chicago and Cleveland.[78] While in North America, he gave multiple lectures on YMCA work in China.[81] He began the return journey on September 14, 1916, by way of the Midwest United States where he hoped to recruit teachers for China.[79]

Crocker attended the 1917 Far Eastern Championship Games in Tokyo, as part of China's delegation.[82] Due to the situation in China during the Warlord Era, the International YMCA committee recalled Crocker to Canada in October 1917.[83] During his time in China, Crocker also promoted reforestation, and helped distribute tree seeds from Canada.[84][85] He summarized his tenure by writing, that the only progress in physical education in China had come via efforts of the YMCA.[68] In an interview in 1924, Crocker described establishment of the Far Eastern Games as "the great feat of his life".[86]

Central-West Canada general secretary[edit]

Upon returning to Canada, Crocker worked on special projects for the YMCA national council, and lectured about the effects of war in China.[87] He was a recurring speaker at YMCA conferences to support the World War I effort in Canada.[88] He appealed to the Canadian public to support programs, when the YMCA was depleted in numbers due to men serving in the war, and was an executive on the "Help Win the War Campaign" launched by the citizen's committee of the YMCA in Brandon, Manitoba.[89] He oversaw fundraising to support the war effort and Canadian troops, and received an endorsement for his work from Lieutenant General Richard Ernest William Turner.[90]

In October 1917, the YMCA of national council Canada restructured into four territorial committees due to growth in Western Canada. Crocker was offered the general secretary position of the Central-West division, which included Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Northwestern Ontario.[91][92] Crocker began work in the position on January 2, 1918, and established his office in Winnipeg.[93] He associated with the Winnipeg YMCA, where he served as acting secretary of the club c. 1917 – c. 1918.[94]

Frequently travelling Western Canada to interact with physical education directors, Crocker implemented YMCA programs despite austerity measures during World War I.[95] He lectured regularly on physical education at YMCA events,[96] and arranged volleyball competitions among YMCA branches in Manitoba, while coaching the team from the Winnipeg Central YMCA.[97]

As secretary of the YMCA's Red Triangle Fund to benefit education for boys, Crocker oversaw fundraising for missions around the world, including China and India.[98] During the Winnipeg general strike in 1919, he recruited neighbourhood boys and YMCA members to staff local firehouses around the clock.[99]

In 1919, Crocker announced plans for a summer campaign to improve living conditions on First Nations reserves.[100] He also sought for the YMCA to assist church missions for First Nations people in Manitoba and Saskatchewan.[101] At the 1920 annual general meeting of the Central-West division, Crocker forecast expansion into industrial and rural fields, and co-operation with other organizations and churches.[102] He collaborated with the Rotary Club to implement work programs for boys in Winnipeg,[103] and was a guest speaker at summer leadership courses for ministers and church members working for the YMCA.[104]

National secretary for physical education[edit]

Returning to Toronto in August 1921, Crocker accepted the position of national secretary for physical education. He supervised all YMCA physical education directors in Canada, travelling across the country for annual inspections.[105] He oversaw national standards for physical education programs, and was a liaison with university and college leagues, secondary school leagues, and other sports governing bodies.[106] He was responsible for training physical education directors at summer schools,[107] and lectured at training classes for mentors.[108] He advocated for Canada to follow the International YMCA model for developing leaders, and for increased attendance at leadership courses.[109]

Crocker was a recurring speaker at YMCA location across Canada, where he promoted physical education, and lectured on the history of the Olympic Games.[110] He spoke often on the history of Canada at the Summer Olympics, and advocated for Canada to send female athletes to international events.[111]

Crocker was a recurring referee at the Ontario YMCA volleyball championship tournament,[112] and at international YMCA tournaments hosted in Ontario.[113] When the Ontario Volleyball Association was established in 1928, Crocker represented the YMCA which included six cities.[114]

Physical education programs made by Crocker followed a "whole man" concept, rather than attempt to produce an athlete.[115] In 1921, he helped establish the Physical Directors' Society of the YMCA in Ontario, to co-ordinate a province-wide physical education program. As the national secretary, he reviewed all proposals submitted for discussion at YMCA general meetings.[116] He introduced sex education summer program to the Physical Directors' Society in 1925, stating that "our teaching should have both elements of truth and love".[117] He also urged for physical education directors to be aware of local laws on birth control.[117]

Representing Canada at the North American Physical Education Society, he was elected president in 1928, the first Canadian to hold the position. He oversaw reorganization of duties to better serve YMCA members, which included the use of laymen in physical education, physical examinations for overall health of participants, and revised teaching methods. He also sought for the society to keep up with changing demands of the world, while providing Christian values to members.[106] After three years of service, he retired as the society's president in May 1930.[63][106]

Retirement and later work[edit]

At age 60, Crocker retired from 36 years of full-time employment with the YMCA as of November 15, 1930, when reaching the compulsory retirement age.[38][63] In 1933, Crocker was named chairman of the athletic committee of the Boys' Work Board and the TUXIS program,[118] and remained in an advisory role on the national physical education board of the YMCA until his death.[38][115]

In 1947, Crocker renewed his affiliation with the Brantford YMCA, where he was a recurring guest speaker.[119] He was named to Brantford's advisory board,[38][120] and was a delegate to the annual meeting of the national council of the YMCA.[121][122]

Royal Life Saving Society Canada[edit]

In 1898, Crocker earned a Bronze Medallion from the Royal Life Saving Society UK. By 1903, he introduced lifesaving courses to the YMCA curriculum, and instructed classes in Toronto and other locations. He also authored articles on water safety and canoeing, published in YMCA bulletins and journals.[123][124] He continued to instruct classes when he worked in Brantford, when a visit to Brantford by Royal Life Saving Society UK founder William Henry increased demand for lifesaving courses.[38]

Crocker was a charter member of the Ontario branch of the Royal Life Saving Society Canada (RLSS), founded on December 10, 1908.[1][125] He was appointed honorary secretary-treasurer of the Ontario branch of the RLSS in 1909, then served as its vice-president in 1910 and 1911. He resumed affiliation with the RLSS Canada in 1917 after returning from China, then served as its vice-president from 1922 to 1933, and as president from 1934 to 1937.[125] He also acted as a liaison between the RLSS and the YMCA.[106]

In 1950, Crocker set forth on documenting the history of the RLSS, resulting in its founding members writing their memoirs.[126] He remained on the board of directors for the RLSS until his death.[38][126]

Amateur Athletic Union of Canada[edit]

Early years[edit]

In 1905, the YMCA Athletic League affiliated with the Canadian Amateur Athletic Union, an early organization which evolved into the Amateur Athletic Union of Canada (AAU of C).[127] From 1905 to 1947, Crocker was the Canadian representative on the International Basketball Rules Commission, which worked with the Amateur Athletic Union of the United States to update the original rules of basketball as made by James Naismith.[14][16]

In 1907, Crocker was named to the board of governors on the Canadian Amateur Athletic Union, as the representative for the YMCA Athletic League.[127] The union sought to expand its influence in Canada and pursued articles of alliance with the Maritime Provinces Amateur Athletic Association.[128]

1908 Summer Olympics[edit]

The Canadian Olympic Committee (COC) was established to select athletes for the 1908 Summer Olympics in London, when the Canadian Amateur Athletic Union and the Amateur Athletic Federation of Canada had unsettled differences. Crocker assisted the Canadian Amateur Athletic Union in arranging regional and national trials to select Olympic athletes.[129] He was subsequently appointed manager of the national team for Canada at the 1908 Summer Olympics, which was first national team organized despite that individuals had competed on behalf of Canada in prior Summer Olympics.[27][120][130]

In response to Tom Longboat's performance in the Olympic marathon, Crocker reported that Longboat was likely "doped", explaining his collapse and subsequent condition.[131] Crocker felt that Longboat had used some stimulant contrary to the rules, and that such an overdose caused the sudden collapse.[132]

At the Olympics, Canadian athletes won three gold, three silver, and ten bronze medals.[133][134] Crocker subsequently submitted the first official national team report to the COC.[36][135] The Tom Longboat situation was subsequently probed by the COC, with Crocker testifying.[131]

Amateur sport commissioner[edit]

Crocker became a Canadian Amateur Athletic Union commissioner in 1909, empowered to oversee registration of amateurs for the district including Brantford.[42][51] He was opposed to athletes participating in professional boxing and wrestling events, and stated that such athletes would be banned from amateur competition sanctioned by the Canada Amateur Athletic Union.[136] He also sought to prevent amateurs from inadvertently competing against professionals, and urged that no prize money be given for boys' races which would disqualify them as amateurs.[137]

In 1910, Crocker was a delegate at the meeting where the Canadian Amateur Athletic Union merged with the Amateur Athletic Federation of Canada to become the AAU of C.[138] He subsequently took leave from AAU of C duties while he was in China.[135]

1920s and the Olympic Games[edit]

After Crocker became the YMCA national secretary for physical education in 1921, he was named to the AAU of C board of governors while representing the YMCA Athletic League from 1921 to 1930.[106][135] He sat on the AAU of C gymnastics committee from 1923 to 1950, and served as the chief gymnastics referee for several years.[135] He was also appointed to the AAU of C special committee to discuss the relation of the physical education director with respect to amateurism, and to suggest rules for the reinstatement of former professionals as amateurs.[139][140]

While with the AAU of C, Crocker stood for amateur ideals and sought for youth to be educated to play sport for "the joy of participating for its own sake".[141][142] He advocated for the AAU of C to provide guidance to youth in sports, and for athletes to represent Canada for the joy of sport without financial gain.[143]

Canadian Olympic Committee becomes permanent[edit]

At the 1922 AAU of C general meeting, Crocker motioned to establish a standing COC, instead of forming a temporary committee prior to each Olympic Games. The permanent COC was to collaborate with provincial organizations to secure funding, chose athletes to represent Canada, and oversee travel and accommodations for the athletes. Patrick J. Mulqueen was elected president, while Crocker served as the secretary from 1922 to 1929, and again from 1933 to 1947.[144][b] Crocker was the honorary manager for each Canadian Olympic team until 1956.[1][27]

1924 Summer Olympics[edit]

In advance of the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris, Crocker was appointed chairman of the track and field sub-committee to select athletes, and named committee members to represent each province.[147][148] He visited track and field championships across Canada to scout Canada's next Olympic athletes.[107][149] He also served as a boxing judge in elimination rounds for the Canadian championships.[150]

Despite disagreements with the Canadian Amateur Swimming Association (CASA), Crocker stated that the AAU of C would pick the Olympic swimmers from CASA members invited to national trials. The disagreement came from the decision of the AAU of C to reduce the number of athletes and officials going to the Olympics due to travel expenses.[151]

When Crocker declined to be Chef de Mission for Canada at the 1924 Summer Olympics due to his commitments to YMCA, Patrick J. Mulqueen replaced him as manager of the Canadian delegation.[107][152] As secretary, Crocker compiled and edited the 72-page COC report, "Canada at the VIII Olympiad, France, 1924".[153]

1924 annual general meeting[edit]

At the 1924 AAU of C annual meeting in Winnipeg, president W. E. Findlay paid tribute to Crocker, Patrick J. Mulqueen, and treasurer Fred Marples, for their efforts in establishing the COC as a permanent body.[154] The AAU of C then passed a resolution to thank the COC for its work in preparing a national team for the 1924 Summer Olympics.[155][156] Crocker reflected that selection of the national team was made difficult when the Government of Canada threatened to withhold CA$10,000 in grant money, if an athlete was not included from the west coast of Canada.[156]

The AAU of C agreed on a new definition of an amateur, which allowed the reinstatement of an individual who unintentionally became professional and wanted to be amateur.[157] Other changes allowed the reinstatement of a physical education director as an amateur, five years after the cessation of teaching as a profession.[155]

1925 to 1928[edit]

In 1925, Crocker was named chairman and secretary of the women's athletics committee, which oversaw female activities within the AAU of C, and choosing of athletes for international competitions.[158]

Crocker sought for Canada to host an international sporting event such as the Olympics, and urged for work to be done as soon as possible. In addressing the Canadian Club of Toronto in 1926, Crocker stated that participation at the Olympic Games improved Canada's world status and "brotherly spirit" among nations.[159]

As chairman of the executive council of the COC in 1927, Crocker led investigations into amateur eligibility of players for the Olympics, which did not allow former professionals to be reinstated as amateurs. At issue were the New Westminster Salmonbellies, who won the Mann Cup as Canadian senior amateur lacrosse champions.[160]

Crocker represented the Ontario Volleyball Association at AAU of C meetings in the late 1920s.[114]

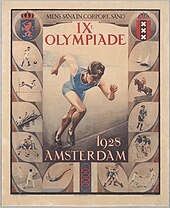

1928 Summer Olympics[edit]

The COC and Crocker asked athletic clubs across Canada to arrange competitions to celebrate the 60th anniversary of Canadian Confederation, using the events as trials for the national championships in Toronto in August 1927, and as a selection process of athletes for Canada at the 1928 Summer Olympics.[161] As the COC secretary, Crocker oversaw the second group of Canada athletes, travelling with them from Quebec City to the Olympics Amsterdam.[162]

While at the Olympics, Crocker served as a boxing judge.[163] He was appointed to the executive of the International Federation of Amateur Boxers to replace James Merrick of Toronto, the former COC president.[164] Crocker also represented Canada at the International Amateur Handball Federation, which had jurisdiction of international basketball games at the time.[135]

1929 annual general meeting[edit]

As chairman of the resolutions committee, Crocker presented a motion to allow amateurs to try out as a professional, but to return to amateur sport if no professional contract was signed.[165] He felt that an athlete's amateur status should remain intact without about signing a professional contract.[145] The motion was defeated despite support by ice hockey delegates, and a different resolution was passed which classified athletes as juniors until their 19th birthday.[165] The AAU of C subsequently allowed for amateurs and professionals to play one another only in exhibition games.[166]

Crocker sought to update the constitution and restructure the AAU of C, by replacing the board of governors with an elected executive committee. His motion was approved, leading to an executive committee including the president, secretary, treasurer, and one member appointed from each of the nine branches. Five members-at-large were appointed by the president, with the committee electing a vice-president.[165]

British Empire Games established[edit]

While planning for the 1928 Summer Olympics, Crocker spoke with journalist Melville Marks Robinson of The Hamilton Spectator, about hosting an international sporting event in Canada. Robinson proposed to host what became the British Empire Games in Hamilton, Ontario, in 1930. After approval of the event from the AAU of C, Crocker assisted in planning and preparations.[167][168]

Canadian athletes won 54 medals at the 1930 British Empire Games; including 20 gold, 15 silver, and 19 bronze.[169] The AAU of C subsequently established a permanent committee to select athletes for the British Empire Games, naming Edward Wentworth Beatty as chairman, and Melville Marks Robinson as secretary.[166] Crocker served on the British Empire Games Association of Canada from 1930 until his death, becoming its honorary vice-president.[167]

Vice-president[edit]

Crocker served as the AAU of C vice-president, and chairman of the track and field athletics committee from 1930 to 1932.[135][170] When hosting duties of the 1931 Canadian track and field championships were awarded to Vancouver, Crocker stated that it was contingent upon construction of a stadium at Hastings Park, and a $2,000-guarantee for the AAU of C. When no progress was made on a stadium, Crocker expected the event to be held instead in Hamilton, Ontario[171] As of the 1931 general meeting, the AAU of C reserved the right to choose the location for the Canadian track and field finals.[172]

The AAU of C created the non-competing amateur class in 1931, which included physical education directors, and club officials who trained or coached younger athletes. The AAU of C also adopted a motion by Crocker that professionals could be reinstated as amateurs after five years absence from competition, and that former professionals could become non-competing amateurs.[172] In 1932, Crocker announced that participants in the YMCA Athletic League were now required to have AAU of C registration cards, as part of his support of a universal registration card for all amateur participants.[173][174]

In December 1931, the AAU of C established formal relations with the Women's Amateur Athletic Federation of Canada. Crocker was one of two officials appointed to liaise with the federation, and to co-operate in selecting female athletes to represent Canada at the Olympic Games and British Empire Games.[172] In the same month, Crocker was chairman of the selection committee for the inaugural Norton H. Crowe Memorial Award, given by the AAU of C to the outstanding athlete-of-the-year. Canadian sprinter Percy Williams was the first recipient.[175] Crocker remained on the selection committee for life.[135]

Crocker helped select athletes for the 1932 Summer Olympics as a member of the COC,[176] and was faced with three athletic clubs in Ontario—London, Hamilton and Toronto—all wanting to hold their marathon race on the same day to qualify for the Olympics.[176] The Ontario branch of the AAU of C preferred the established date at the Monarch Athletic Club in Toronto, rather than in Hamilton or at a new club in London. Representatives from Southwestern Ontario felt that Toronto was being greedy, and resented the dominance of Toronto-based officials on the executive of the Ontario branch of the AAU of C.[177] Crocker opted to conduct the Olympic trials for the marathon in London,[177] but also selected for the national team, the two runners who finished first and second place in the Hamilton marathon.[176] Crocker then attend the 1932 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, as part of the Canadian delegation.[120]

President[edit]

First term[edit]

The 1932 AAU of C general meeting was hosted in Ottawa at the Château Laurier in December 1932,[178] where Crocker was elected president to succeed James I. Morkin of Winnipeg.[179][180] Crocker remained chairman of the resolutions committee,[181] and made a series of appointments to fill the standing committees for the AAU of C.[182]

Crocker chaired committees which evaluated the definition of an amateur with respect to paid recreational sports directors and physical education directors.[143] The AAU of C disallowed teachers giving part-time instruction from competing in amateur sports at the same time, but instead allowed the teachers to return to competing in amateur sports 15 days after the end of giving instructions. The change permitted a person whose primary employment was academic instruction, to give part-time physical education instruction without being classified as a professional.[181] The AAU of C declined a proposal to allow a professional in one sport to be an amateur in a different sport, and referred the matter to a special committee appointed by Crocker to explore impacts of the proposal on amateur eligibility for the Olympics and other international sporting associations.[179]

As president, Crocker enforced registration rules for amateurs. When the registration committee discovered that two active professionals were issued amateur registrations for hockey in Alberta, Crocker order the two players suspended or the Alberta branch of the AAU of C would be suspended.[183] He also expressed concerns about the amateur eligibility of teams in the Interprovincial Rugby Football Union (IRFU), stating that the league might be disqualified from the national playoffs.[184] He recommended to the Ontario and Quebec branches of the AAU of C, that no registration cards be issued to players in the IRFU, meaning that the league would operate as if it was unaffiliated.[185]

Second term[edit]

At the 1933 AAU of C general meeting held in the Fort Garry Hotel in Winnipeg, Crocker was re-elected president by acclamation.[186][187] In his opening remarks, Crocker stressed that sportsmanship should be the goal of all amateur athletes, and victory as secondary. He felt that the goals of the AAU of C were to protect youth recreation in Canada, and cautioned that the pursuit of gate receipts compromised amateurism. He sought for the committees of AAU of C branch to be truly representative of their districts, and to conduct business with confidence of the people.[188]

During Crocker's first term, the AAU of C questioned the amateur status of players in multiple sports due to the mingling of amateurs and professionals within the same sport. He sought to resolve this with a proposal to eliminate a clause in the constitution which gave executives the power to approve exhibition games between amateur and professional teams for charitable purposes.[189] Following actions taken by the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA), the AAU of C permitted amateurs to tryout with professional clubs without losing amateur status, proving that no professional contract was signed.[190][191]

Southwestern Ontario branch established[edit]

Crocker supported creation of the Southwestern Ontario branch of the AAU of C, and expanding the territory of the Ottawa branch, both of which were taken away from the Ontario branch.[177] The AAU of C executive approved establishment of the Southwestern Ontario branch, after a petition claiming that clubs in the area had no voice on the Ontario branch executive. Crocker named a committee to determine boundaries for the new branch, which expected to have a greater population than any other AAU of C branch.[192] He also sat on the organizing committee for the new branch, which sought a regular schedule of athletic meets for continual competitions.[193]

The Southwest Ontario branch was formally established at Brantford on January 6, 1934, with Crocker in attendance. The new branch adopted a constitution and by-laws aimed at growing sports, and supporting local clubs. The branch organized itself into eight zones; Brantford, Hamilton, Kitchener, London, Niagara Falls, Sarnia, Stratford, and Windsor.[194] At Crocker's suggestion, each zone elected a member to the executive committee of the branch.[195]

In opposition to the new branch, the Ontario Amateur Sports Federation was formed in January 1934, by representatives of ten provincial sports governing bodies, and sought to petition the AAU of C for one branch to control the whole province of Ontario.[196] Crocker asserted that the creation of new provincial sport body to be illegal.[177] In response to clubs ignoring the new branch and seeking approval from the Ontario branch, he declared that any sporting event staged without approval of the appropriate AAU of C branch, would result in a suspension.[197]

1934 general meeting[edit]

The Royal York Hotel in Toronto hosted the AAU of C general meeting in November 1934.[198] When Crocker was concerned that commercial interests in boxing and wrestling had petitioned the Government of Canada to take away control of these sports from the AAU of C, he then urged that the AAU of C petition the government for control of all amateur sport in Canada to prevent a rivalry. He felt that the future of amateur sports lay with youth, and recommended that AAU of C branches organize amateur sports for high school students in co-operation with secondary school associations.[199][200]

Past-president[edit]

Crocker declined a third term due to health concerns, and was succeeded by W. A. Fry as the AAU of C president.[146][198] Crocker remained a member of the AAU of C executive committee as the past-president from 1934 to 1936, and as a representative of the Southwestern Ontario branch from 1934 to 1956.[135] He focused his time in building up the new Southwestern Ontario branch, which faced financial difficulty and had less than 1,000 registrants as of 1934. He also felt that the AAU of C needed new people involved, and that it included "too many past presidents for the good of amateur sport".[198] In October 1935, he was elected an honorary vice-president of the Southwestern Ontario branch at its first annual meeting.[201]

1936 Winter and Summer Olympics[edit]

The COC planned to send 120 athletes to the 1936 Winter Olympics in Germany, but Crocker noted a lack of funds to pay travel expenses, except for the Canada men's national ice hockey team financed by the CAHA.[202] When Canada won the silver medal, it was the first Winter Olympics in which Canada did not win gold.[203] When the second-place finish was heavily scrutinized by media in Canada, Crocker felt that any dissatisfaction should be directed towards the CAHA, which "had asked to be allowed to run its own show", instead of the AAU of C being in charge.[204]

After the Olympics, the CAHA changed its definition of an amateur, without approval of the AAU of C. The change threatened to end the alliance between the two largest sports bodies in Canada at the time. Crocker felt that Canadian hockey had become professionalized, and that it would be best to arrange a professional section within the CAHA, similar to the structure of the Dominion Football Association.[205] He later urged for AAU of C branches to organize hockey within their territories, since he felt that the CAHA was no longer an amateur organization.[206]

Crocker denied reports that he resigned from the COC, after he had taken rest on doctor's orders and would not attend the 1936 Summer Olympics due to health. He also stated that the COC refused to accept his resignation, and he remained as secretary with a reduced workload.[207] In November 1936, the AAU of C discussed multiple resolutions for reorganizing the COC. After Crocker and Patrick J. Mulqueen motioned to dissolve the current COC, the AAU of C agreed to establish a special committee to prepare for the next Olympic Games, including the president, secretary, one representative from each AAU of C branch, and one representative from each allied sports governing body in Canada.[204]

1938 British Empire Games[edit]

Crocker served as chairman of the AAU of C boxing and wrestling committee from 1937 to 1951.[135] He was expected to be coach of the Canadian boxing and wrestling team for the 1938 British Empire Games, until E. J. Don Rowand was named,[208] and Crocker instead managed Canada's track and field team.[209] As president and secretary of the British Empire Games Association of Canada, Crocker was also the manager and treasurer of the national delegation to the event, and travelled with the Canadian contingent aboard MV Aorangi from Vancouver to Sydney, Australia.[210]

Canadian athletes won 13 gold, 16 silver, and 15 bronze medals at the games.[169] On the return trip, Crocker and the team sailed from Sydney to Vancouver aboard RMS Niagara.[209] Shortly after returning home, Crocker's brown leather club bag covered in steamship and hotel labels was stolen from his car. The bag which contained travel items from the British Empire Games, was recovered two days later.[211]

Later years[edit]

Crocker was an honorary vice-president of the Ontario Volleyball Association c. 1938,[212] and served as chairman of the AAU of C committee for resolutions from 1939 to 1955.[135]

In preparation for the 1948 Summer Olympics in London, Crocker served as treasurer of the COC.[135] He remained on the executive in 1948, when it was enlarged to have representation from all provinces in Canada. The Canadian Olympic Association replaced the COC by 1952, as a body independent of the AAU of C. Crocker assisted in the transition and served the Canadian Olympic Association in an advisory role until his death.[213]

Later in life Crocker compiled a history of amateur sporting organizations in Ontario.[214] His later contributions to the AAU of C included sitting on the awards committee from 1947 to 1951, chairman of the hall of fame nominating committee from 1947 to 1955, chairman of the historical committee from 1950 to 1959, and honorary vice-president from 1954 to 1959.[135]

University of Western Ontario[edit]

Crocker became director of the physical education department of the University of Western Ontario in November 1930.[215][216] His responsibilities included coaches of the intercollegiate sports teams for the Western Mustangs, arranging travel and accommodations to road games and tournaments, organizing intramural sports, and administration of the athletic department.[216]

Physical education courses were not yet offered when Crocker joined the university, and intramural programs used facilities at the London YMCA, the London Armoury, London Industrial School, and the London Club.[217] By 1932, he established intramural programs for cross country running, boxing, wrestling, and expanded the basketball and rugby programs.[23] In 1934, he convinced university administration to construct a field house on campus for physical education and intramural sports. Construction of the field house was delayed until 1948, due to the Great Depression in Canada and World War II. He also sought for increased funding for physical education, such that programs did not depend on gate receipts from intercollegiate sports.[218]

Crocker took interest in the individual student, and had an open-door policy at his office. He found jobs for students who could not afford their studies, including part-time work at the local YMCA. After becoming involved in student affairs, the university appointed him to the bursary committee and the cafeteria committee.[219] He sought better nutrition at the student cafeteria, and affordable healthy eating by buying food in bulk.[217]

During Crocker's tenure, the Western Mustangs men's ice hockey team won its first Canadian Interuniversity Athletics Union (CIAU) championship in the 1932–33 season.[220] When the London Arena was not available for the 1936–37 season, Crocker arranged to play home games in Brantford, and have practices an outdoor rink on campus.[221] To improve the quality of basketball at the university, Crocker arranged local high school basketball tournaments to scout and recruit players.[222]

Crocker felt that it was unfair to the students and faculty to lengthen the Western Mustangs football season beyond intercollegiate competition, and declared that the football team would not compete for the national championship in 1938, if it won the intercollegiate title.[223] Crocker went ahead with plans for the football team during World War II, despite that no decision had been made whether the CIAU would operate.[224] When intercollegiate football collapsed due to World War II, Crocker considered placing the football team in the Ontario Rugby Football Union, but it was impossible to agree on a schedule due to military requirements on the training of physically fit students.[225] Instead of being members of any football league, Crocker invited Ontario Rugby Football Union teams to play exhibition games at the university.[226]

In 1944, Crocker announced the formation of a Western Ontario branch of the Canadian Physical Education Association.[227] He arranged the annual meeting for the association, and served as honorary president.[228] During the 1944 annual meeting for the Canadian Physical Education Association, Crocker presided over the national radio broadcast of "Sports College of the Air".[229]

Crocker sought to establish a Bachelor of Arts degree in physical education, as a means to produce teachers at secondary schools and instructors at recreational institutes.[230] The university divided its physical education program in May 1946, resulting in one branch for team and individual athletics; and a separate branch for physical education, health, and intramurals, with Crocker as director of the latter branch.[231] Crocker then resurrected his plans to construct Thames Hall, a field house on the campus for physical education. He also hired Alex Dewar as an assistant, a former YMCA physical education who had a master's degree in physical education. They established a four-year Bachelor of Arts degree program which commenced in autumn 1947.[230]

Retirement and philately[edit]

Crocker retired as the physical education of University of Western Ontario on June 30, 1947. He remained a guest lecturer in classes on the history of physical education.[12][232] He also assisted with the design for Thames Hall, and fundraising for its construction, completed in 1949.[27][233]

In retirement, Crocker also served as president of the Philatelic Society of London, Ontario,[12] and visited the university twice per week as curator of the A. O. Jeffery Stamp Collection.[214][232] He became interested in stamp collecting while in China, and preferred sports themes including the Olympic Games, and Canadian and British Commonwealth of Nations stamps.[232][234]

In a 1956 interview, Crocker stated that while he "thoroughly enjoyed" his work with the university, his work with the YMCA was his "still his first love".[38]

Personal life[edit]

Crocker married Reeta Helen Stuart Clark of St. Stephen, on May 1, 1901.[3] They honeymooned with a canoe trip along the French River, before settling in Toronto,[235] then raising a son and a daughter.[236] The couple took frequent canoe trips along the French River, to Algonquin Provincial Park, and to the Toronto Islands.[237] Other recreational activities included camping, swimming, boating, and fishing.[4][123]

In Brantford, Crocker participated in curling and lawn bowling as a member of the Heather Club.[238] He served as secretary-treasurer of the club,[239] and was selected as skip of a curling rink.[240] In 1909, he assisted with fundraising to expand the tuberculosis hospital in Muskoka, by the sale of postage stamps in Brantford.[241] His wife was a pianist and a member of the women's auxiliary of the Brantford YMCA.[242]

Crocker and his family moved to China in 1911,[64][236] and lived within the Shanghai International Settlement,[62] where he became a commissioned lieutenant in the Shanghai Volunteer Corps in 1916.[91] While in China, his wife was active in the Shanghai social scene, took interest in the role of women, and lectured in favour of Montessori education for children.[72][243] The Crockers also welcomed locals into their home to encourage further education, and host discussions similar to Crocker's YMCA leadership camps in Canada.[243]

The Crockers moved from China to Winnipeg in 1917,[83] and became a member of the Rotary Club of Winnipeg.[244] When Crocker was stricken by the 1918 flu pandemic, his wife worked full-time to take care of him and the family.[99] He was a lifetime dog owner except his time in China. As a member of the Canadian Kennel Club, he bred and showed dogs while living in Winnipeg.[24]

Crocker and his wife returned to Toronto in 1921, where they lived until her death from pernicious anemia in 1930.[237] On a summer fishing trip in 1930, he visited Rainbow Country in Northern Ontario, where he purchased an island cottage near Whitefish Falls which he named "Sous Bois".[119] Crocker moved to London later in 1930, then returned to Brantford after his retirement from the University of Western Ontario in 1948.[38][214]

With his health failing later in life, Crocker was comforted being outdoors with nature.[4] While vacationing at his cottage in August 1948, Crocker had a coronary thrombosis, and was the first civilian patient to be airlifted via the Brantford Airport to the hospital.[245][246] In autumn 1953, Crocker's doctors suspected that he had a bone tumor, but no clear diagnosis was given. Having difficulty getting out of bed and unable to get long-term care locally, he moved to Sidney, British Columbia, to be cared for in a warmer climate. He recovered by 1954, but his eyesight worsened due to glaucoma and cataracts.[246]

Later in life, he travelled once per year to Ontario by train, to attended sporting events to feel the atmosphere despite not seeing the competitions well.[247] He declined to attend the 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne due to declining eyesight.[120] He became a member of his local white cane club, to speak with other blind persons. After surgery to remove a cataract in his left eye, Crocker suffered a fatal stroke.[248] He died on November 27, 1959, at the Royal Jubilee Hospital, and was interred in Royal Oak Burial Park in Victoria, British Columbia.[21]

Honours and legacy[edit]

Crocker received multiple honours from the YMCA during his lifetime. In 1916, the International YMCA College granted him an honorary Master of Physical Education degree, for a thesis and his lectures on work done in China, and for establishing the Far Eastern Championship Games.[12][23][81][249] In 1924, the International North American Physical Education Society made him a fellow in physical education for the YMCA in the United States and Canada.[106] On December 11, 1930, Crocker was the guest of honour at a retirement banquet held at the Toronto Central YMCA.[250] As a retirement gift, his colleagues bought him a new Dodge automobile, the first car he owned.[115] He received a life membership in the Brantford YMCA in March 1950,[251] and was made a life member of the YMCA of Canada during its centennial celebration in January 1951.[81][252] The YMCA subsequently gave the J. Howard Crocker Award, to the association with the top score in its annual physical education program audit.[253][254]

At the 1925 AAU of C general meeting, Joseph Thompson, the speaker of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario, presented Crocker with a silver tea service in recognition of his work on the COC in preparation for the 1924 Summer Olympic Games, including his thorough records and reporting.[255][256] In October 1934, he received the past-president's medal from the AAU of C.[257]

In 1930, the Royal Life Saving Society UK awarded Crocker the Distinguished Service Medal for his work in Ontario. He was made a life governor of the RLSS in 1938. In 1950, he received the bronze star for the Distinguished Service Medal, and the silver star in 1953.[258]

In 1948, Crocker was one of the inaugural five recipients of the R. Tait McKenzie Award; given by the Canadian Association for Health, Physical Education and Recreation, in recognition of his lifetime contributions to physical and health education.[259] In July 1959, he was named an honorary president of the Canadian Association for Health, Physical Education, and Recreation.[73]

Crocker was granted a lifetime membership in the University of Western Alumni Association in 1949.[260] At the 146th convocation of the University of Western Ontario in March 1950, he received honorary Doctor of Law degree and a portrait of himself panted by Claire Bice.[261] He received a life membership in the Royal Philatelic Society of Canada in 1951.[234][262]

After Crocker died, The Canadian Press remembered him as, "one of the greatest figures in Canadian amateur sports".[20] He was remembered by the Victoria Daily Times as, "one of the most illustrious figures in amateur sports in Canada".[21]

Crocker has received several posthumous honours. In recognition of his work in athletics, he was inducted into the builder category of the AAU of C Hall of Fame in 1960, which later became the Canadian Olympic Hall of Fame.[263][264] The International Centre for Olympic Studies at the University of Western Ontario annually hosts the John Howard Crocker Lecture, inaugurated in 1991.[27] The New Brunswick Sports Hall of Fame inducted Crocker into its builder category in 2023.[265]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The Fédération Internationale de Volleyball credits Crocker for introducing volleyball to China via the YMCA.[70] Crocker wrote in a letter than the introduction of volleyball to China occurred in 1912.[69]

- ^ Melville Marks Robinson served as secretary of the Canadian Olympic Committee from 1929[145] to 1933.[146]

Sources[edit]

- Keyes, Mary Eleanor (October 1964). John Howard Crocker LL. D., 1870–1959 (Thesis). London, Ontario: University of Western Ontario. OCLC 61578234.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e University of Western Ontario (1960). "J. Howard Crocker fonds". Archives Association of Ontario. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), pp. 13–14

- ^ a b Vital Statistics from Government Records (RS141), Fredericton, New Brunswick: Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, May 1, 1901

- ^ a b c Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 15

- ^ Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 16

- ^ Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 17

- ^ Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 27

- ^ a b Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 19

- ^ Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 25

- ^ Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 18

- ^ Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 26

- ^ a b c d e Byrnes, Bruce (April 11, 1947). "Athletic Director Leaving in June; Dewar Successor". UWO Gazette. London, Ontario. p. 1.; Byrnes, Bruce (April 11, 1947). "Athletic Director (Continued from Page 1)". UWO Gazette. London, Ontario. p. 3.

- ^ a b Daly, Brian I. (2013). Canada's Other Game: Basketball from Naismith to Nash. Toronto, Ontario: Dundurn Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 9781459706347.

- ^ a b "Cage Players Luncheon Guests Of Brantford 'Y'". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. April 13, 1953. p. 15. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 20

- ^ a b c Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 29

- ^ "Crocker, John Howard". The Register. Fredericton, New Brunswick: The Associated Alumni of the University of New Brunswick. 1924. p. 76.

- ^ a b "Personal Interest". The Halifax Herald. Halifax, Nova Scotia. June 6, 1898. p. 8. Archived from the original on March 23, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Connolly Got Three Medals". The Boston Globe. Boston, Massachusetts. September 12, 1897. p. 2. Archived from the original on March 24, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Sporting Great, Dr. Crocker Dies At Coast". Winnipeg Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. The Canadian Press. November 30, 1959. p. 47. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Top Athletic Star Dr. J. H. Crocker Dies". Victoria Daily Times. Victoria, British Columbia. November 28, 1959. p. 3. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Mr. Crocker Will Be Sent To China". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. May 18, 1911. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Western's Director of Physical Education". Bulletin of Alumni Association of University of Western Ontario Medical School. London, Ontario. January 1932. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 21

- ^ "Maritime Boys' Camp". The Halifax Herald. Halifax, Nova Scotia. July 10, 1899. p. 7. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 31

- ^ a b c d e f "John Howard Crocker Olympic Studies Lecture". University of Western Ontario. 2022. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- ^ Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), pp. 32–34

- ^ Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 35

- ^ Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 37

- ^ Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), pp. 40–41

- ^ "In the World of Sport". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. February 21, 1901. p. 8. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ Crocker, J. Howard (July 10, 1902). "Basketball: Expert Notes on Playing the Game". Durham Chronicle and Grey County Advertiser. Durham, Ontario. p. 7. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Basketball League Has Been Formed". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. November 9, 1905. p. 5. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), pp. 44–45

- ^ a b "Crocker, J. Howard (John Howard), 1870–1959". Toronto Public Library. 2022. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- ^ "Secretary of Y.M.C.A." Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. October 20, 1908. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 20, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Henderson, Jim (September 22, 1956). "Retire at 60? No, Sir! Dr. J. Howard Crocker Carved a Second Career". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. p. 18. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b "Farewelled". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. June 28, 1911. p. 2. Archived from the original on April 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), pp. 45–46

- ^ "Aid To Injured". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. January 21, 1909. p. 7. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b "Brantford Players Lost in Basketball at Hamilton by 39–12". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. January 19, 1909. p. 5. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Hamilton Juniors Defeated Brantford in Basketball Here Last Night". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. January 21, 1909. p. 2. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Y.M.C.A. Athletic Events Have Good Field Last Night". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. June 4, 1909. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Entries For Y.M.C.A. Sports". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. September 16, 1910. p. 2. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "City and Vicinity: Swimming Club". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. October 6, 1910. p. 6. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "City and Vicinity: To Act as Judges". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. February 24, 1909. p. 6. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Notes of Sport". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. December 22, 1908. p. 3. Archived from the original on April 20, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "A Junior League". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. April 13, 1909. p. 3. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "City News". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. May 4, 1909. p. 2. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b "Rules for Walking Race". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. April 16, 1910. p. 5. Archived from the original on April 20, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Ready For Walking Race". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. May 21, 1910. p. 11. Archived from the original on December 29, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2023.; "The Expositor Race for all Walkers". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. April 10, 1911. p. 5. Archived from the original on April 21, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Athletics". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. May 17, 1909. p. 3. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Bicycle Contest Attracted Much Interest in This City Last Evening". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. July 15, 1909. p. 3. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Athletics". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. April 19, 1910. p. 3. Archived from the original on April 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "City and Vicinity: Addressed Class". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. April 24, 1911. p. 6. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Church News". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. April 8, 1911. p. 8. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "City and Vicinity: At Sydenham". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. January 16, 1911. p. 6. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Sunday In Churches". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. January 17, 1910. p. 5. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b "From Small Beginnings, the Y.M.C.A. Has Become Vital Community Centre". Brantford Expositor Centennial Edition. Brantford, Ontario. October 11, 1952. p. 230. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Ex-Y Official Here, Canadian Sports Great Dr. John Crocker Dies". The Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. November 30, 1959. p. 2. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Mr. J. H. Crocker Tells Of Work at Shanghai". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. February 15, 1912. p. 7. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c National Council of Young Men's Christian Associations of Canada (November 1930). "Howard Crocker's Resignation". The News Bulletin. Toronto, Ontario. pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b "City and Vicinity: Left on Thursday". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. August 26, 1911. p. 6. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ Jones, Gordon R. (November 4, 1911). "Chinese Rebels Having Easy Time in Capturing Cities". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b "Letter from J. H. Crocker". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. November 30, 1911. p. 8. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "J. Howard Crocker Writes of China". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. December 26, 1911. p. 9. Archived from the original on April 20, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Y.M.C.A. Supremacy in Physical Education". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. January 19, 1918. p. 18. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Another Letter From J. H. Crocker". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. June 25, 1912. p. 10. Archived from the original on April 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "History – Volleyball". Fédération Internationale de Volleyball. 2022. Archived from the original on December 4, 2022. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- ^ Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 52

- ^ a b Jones, Gordon R. (October 29, 1914). "Disappearance of German Merchantmen a Sore Blow". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. p. 10. Archived from the original on April 21, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b Redmond, Gerald (July 11, 1978). "Van Vliet: right man for the job". Edmonton Journal. Edmonton, Alberta. p. 33. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "J. Howard Crocker". Brandon Weekly Sun. Brandon, Manitoba. January 30, 1913. p. 22. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.; "J. H. Crocker Is Home". The Acton Free Press. Acton, Ontario. November 30, 1916. p. 11. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Sporting Comment". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. July 25, 1914. p. 13. Archived from the original on April 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 57

- ^ a b "Athletic Awakening In China Is Helped By President Says J. H. Crocker". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. April 24, 1916. p. 7. Archived from the original on May 1, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b "Awakening of Chinese to Value of Athletics has Come". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. March 1, 1916. p. 5. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b "J. H. Crocker Returning to Work in China". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. September 12, 1916. p. 5. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "J. Howard Crocker on His Way Home". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. April 15, 1916. p. 18. Archived from the original on April 21, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 153

- ^ Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 56

- ^ a b Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 61

- ^ "J. H. Crocker, Empire Builder, Worker for Christ in China Tendered Banquet by Friends". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. April 25, 1916. p. 8. Archived from the original on April 30, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Canadian Tree Seeds for Chinese Soil". The Western Call. Vancouver, British Columbia. June 4, 1915. p. 1.

- ^ "Completing Thirtieth Year in Y.M.C.A. Physical Work". Winnipeg Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. September 24, 1924. p. 5.

- ^ "To Visit City". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. December 4, 1917. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 21, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Business Men Invited To Conference At Y". The Brandon Daily Sun. Brandon, Manitoba. November 16, 1917. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 24, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Citizens Committee Launch Campaign $15,000 for YMCA". The Brandon Daily Sun. Brandon, Manitoba. November 21, 1917. p. 2.

- ^ "Report Activities In Y.M.C.A. Work". Winnipeg Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. January 25, 1919. p. 34. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.; "General Turner Endorses Work of the Y.M.C.A." The Brandon Daily Sun. Brandon, Manitoba. May 6, 1919. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 24, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ a b Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), p. 62

- ^ "Reorganization of Y.M.C.A. Work". Winnipeg Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. October 10, 1917. p. 7. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "City and District". Winnipeg Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. January 2, 1918. p. 5.

- ^ "High Lights in the History of Winnipeg Y.M.C.A. and the Reason of its Present Indebtedness". Winnipeg Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. April 25, 1927. p. 5.

- ^ Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), pp. 62–63

- ^ "Y.M.C.A. Institute Opens Next Week". Winnipeg Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. February 7, 1920. p. 81. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Winnipeg Volley Ball Team Plays Here Saturday". The Brandon Daily Sun. Brandon, Manitoba. February 26, 1920. p. 14.

- ^ "The "Y" Asks Canada's Boys for $35,000". Manitoba Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. April 29, 1919. p. 5.

- ^ a b Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), pp. 64–65

- ^ "To Improve Conditions of Indians". Winnipeg Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. March 28, 1919. p. 7.

- ^ "Plan to Carry Y.M.C.A. Work to the Indians of the Prairie West". Brandon Daily Sun. Brandon, Manitoba. March 26, 1919. p. 3. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Central West Y.M.C.A. Meets". The Winnipeg Tribune. Winnipeg, Manitoba. February 13, 1920. p. 21.

- ^ "Active Committee of Rotarians Working to Help Winnipeg Boys". Winnipeg Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. May 1, 1920. p. 25.

- ^ "C. M. Copeland, First Secretary of Y.M.C.A. Here, Returning". Winnipeg Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. July 14, 1920. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 24, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), pp. 65–66

- ^ a b c d e f Keyes, Mary Eleanor (1964), pp. 67–68

- ^ a b c "Tommy Town Considered As One of Likely Candidates For Canada's Olympic Team". Brandon Daily Sun. Brandon, Manitoba. October 20, 1923. p. 4. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Mentors End Training Class". The Winnipeg Tribune. Winnipeg, Manitoba. March 6, 1926. p. 31.

- ^ "Y Leaders Banquet". Charlottetown Guardian. Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. October 1, 1925. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Development of Athletics". Cranbrook Herald. Cranbrook, British Columbia. February 24, 1927. p. 1.; "Development of Athletics (Continued from Page One)". Cranbrook Herald. Cranbrook, British Columbia. February 24, 1927. p. 3.

- ^ "Second Annual Sports Banquet at Y Last Night". Charlottetown Guardian. Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. March 28, 1924. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "London 'A' Team Put Brantford out of Provincial Volley Ball Tournament". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. March 17, 1923. p. 16. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Brantford Team in Volleyball Tourney". Brantford Expositor. Brantford, Ontario. April 6, 1925. p. 9. Archived from the original on May 2, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.