Irish Catholic Martyrs

| Irish Catholic Martyrs | |

|---|---|

Irish Catholic Martyrs formally recognized | |

| Born | Ireland |

| Died | between 1537 (Venerable John Travers) – 1 July 1681 (Saint Oliver Plunkett), Ireland, England, Wales |

| Martyred by | Monarchy of England |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 3 were beatified on 15 December 1929 by Pope Pius XI 1 was beatified on 22 November 1987 by Pope John Paul II 18 were beatified on 27 September 1992 by Pope John Paul II |

| Canonized | 1 (Oliver Plunkett) was canonized on 12 October 1975 by Pope Paul VI |

| Feast | 20 June, various for individual martyrs |

Irish Catholic Martyrs (Irish: Mairtírigh Chaitliceacha na hÉireann) were 24 Irish men and women who have been beatified or canonized for both a life of heroic virtue and for dying for their Catholic faith between King Henry VIII and Catholic Emancipation in 1829. The canonization of Oliver Plunkett, who had been executed in London, as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales in 1975 raised considerable public interest in other Irishmen and Irishwomen who had similarly died for their Catholic faith in the 16th and 17th centuries. On 22 September 1992 Pope John Paul II beatified an additional 17 martyrs and assigned June 20, the anniversary of the 1584 martyrdom of Archbishop Dermot O'Hurley, as their feast day.[1] Many other causes for Roman Catholic Sainthood, however, remain under investigation.

History[edit]

The persecution of Catholics in Ireland in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries came in waves, caused by a reaction to particular incidents or circumstances, with intervals of comparative respite in between.[2] During the religious persecution of the Catholic Church in Ireland that began under Henry VIII and ended only with Catholic Emancipation in 1829, the Irish people, according to Marcus Tanner, clung to the Mass, "crossed themselves when they passed Protestant ministers on the road, had to be dragged into Protestant churches and put cotton wool in their ears rather than listen to Protestant sermons."[3]

According to historian and folklorist Seumas MacManus, "Throughout these dreadful centuries, too, the hunted priest -- who in his youth had been smuggled to the Continent of Europe to receive his training -- tended the flame of faith. He lurked like a thief among the hills. On Sundays and Feast Days he celebrated Mass at a rock, on a remote mountainside, while the congregation knelt on the heather of the hillside, under the open heavens. While he said Mass, faithful sentries watched from all the nearby hilltops, to give timely warning of the approaching priest-hunter and his guard of British soldiers. But sometimes the troops came on them unawares, and the Mass Rock was bespattered with his blood, -- and men, women, and children caught in the crime of worshipping God among the rocks, were frequently slaughtered on the mountainside."[4]

Henry VIII[edit]

Religious persecution of Catholics in Ireland began under King Henry VIII (then Lord of Ireland) after his excommunication in 1533. In the process, the King and Thomas Cromwell continued Cardinal Wolsey's policies of centralizing government power in Ireland and seeking to completely destroy the political and military independence of both the Old English nobility, the Irish clans, and the Gaelic nobility of Ireland. This, in addition to the King's religious policy, ultimately triggered Old English aristocrat Silken Thomas, 10th and last Earl of Kildare, to launch a 1534-1535 military uprising against the rule of the House of Tudor in Ireland.[5]

The Irish Parliament adopted the Acts of Supremacy, which declared the Irish Church subservient to the State.[6] In response, Irish bishops, priests, and laity who continued to pray for the pope during Mass were tortured and killed.[7] The Treasons Act 1534 defined even unspoken mental allegiance to the Holy See as high treason. Many were imprisoned on this basis. Alleged traitors who were brought to trial, like all other British subjects tried for the same offence prior to the Treason Act 1695, were forbidden the services of a defence counsel and forced to act as their own attorneys.[8]

According to D.P. Conyngham, "Though the faithful underwent fearful persecutions toward the latter part of the reign of Henry, few publicly suffered martyrdom. Numbers of the monks and religious were killed at their expulsion from their houses, but the King's adhesion to many articles of Catholicity made it too hazardous for his agents in Ireland to resort to the stake or the gibbet. In fact, Henry burned at the same stake Lutherans, for denying the Real Presence, with Catholics, for denying his supremacy."[9]

On c.30 July 1535, Venerable Fr. John Travers, a graduate of Oxford University and the Chancellor of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, was executed in Dublin for writing a volume denouncing the Act of Supremacy. As this had not yet been made into a crime in Ireland, Fr. Travers was instead tried at the summer assizes for high treason and involvement in the recent rebellion of Silken Thomas. According to historian R. Dudley Edwards, Fr. Travers had acted only in non-combatant roles as a peace negotiator and had even offered himself as a hostage to the King's forces. Fr. Travers also had no political or financial dependency, familial links, or nationalist feelings of loyalty towards the Earls of Kildare and his involvement in the uprising was motivated only by a desire to defend the independence of the Catholic Church in Ireland from being lost to control by the State. Following his inevitable conviction, Fr. Travers was burned at the stake in the Common then known as, "Oxmantown Green", part of which has since become Smithfield Market on the city's Northside.[10][11]

According to Philip O'Sullivan Beare, "[John Travers] wrote something against the English heresy, in which he maintained the jurisdiction and authority of the Pope. Being arraigned for this before the King's court, and questioned by the judge on the matter, he fearlessly replied - 'With these fingers', said he, holding out the thumb, index, and middle fingers, of his right hand, 'those were written by me, and for this deed in so good and holy a cause I neither am nor will be sorry.' There upon being condemned to death, amongst other punishments inflicted, that glorious hand was cut off by the executioner and thrown into the fire and burnt, except the three sacred fingers by which he had effected those writings, and which the flames, however piled on and stirred up, could not consume."[12]

In 1536, Venerable Fr. Charles Reynolds (Irish: Cathal Mac Raghnaill), the Hiberno-Norse Archdeacon of Kells, was posthumously attained for high treason in the Attainder of the Earl of Kildare Act 1536 for successfully urging Pope Paul III to excommunicate King Henry VIII over his divorce, his uncanonical remarriage, and the Caesaropapism of his religious policy.[13]

When the Suppression of the Monasteries was extended to Ireland as well, the Annals of the Four Masters reports for the year 1540, "The English in every place throughout Ireland where they established their power, persecuted and banished the nine religious orders, and particularly they destroyed the monastery of Monaghan, and beheaded the guardian and a number of friars."[14] A 1935 article by historian L.P. Murray identifies the martyred erenagh of Monaghan Monastery as Fr. Patrick Brady and adds that he was beheaded alongside 16 fellow Franciscan Friars.[15]

Elizabeth I[edit]

Even though she continued the plantation of Ireland with English settlers, the persecution of Catholics ceased after the accession of the Catholic Queen Mary, but after Mary's death in November 1558, her sister Queen Elizabeth I arranged for Parliament to pass the Act of Supremacy of 1559, which re-established the control by the State over the Church within her dominions and criminalized religious dissent as high treason. While reviving Thomas Cranmer's prayerbook, the Queen ordered the Elizabethan religious settlement to favour High Church Anglicanism, which preserved many traditionally Catholic ceremonies. Meanwhile, the Acts of Supremacy and Uniformity (1559), the Prayer Book of 1559, and the Thirty-Nine Articles (1563) mixed the doctrines of Protestantism and Caesaropapism.[16]

In 1563 the Earl of Essex issued a proclamation, by which all Roman Catholic priests, secular and regular, were forbidden to officiate, or even to reside in Dublin or in The Pale. Fines and penalties were strictly enforced for Recusancy from the Anglican Sunday service; before long, torture and death were inflicted. Priests and religious were, as might be expected, the first victims. They were hunted into the Mass rocks in mountains and caves; and the parish churches and few monastic chapels which had escaped the rapacity of King Henry VIII were also destroyed.[17]

From the early years of her reign, pressure was put on all her subjects to conform to the "Established Church" of the realm or be considered guilty of high treason. Prosecutions for Recusancy and refusals to take the Oath of Supremacy, the issuing of torture warrants, and the use of priest hunters escalated rapidly. It ultimately resulted in Pope Pius V's 1570 papal bull Regnans in Excelsis, which, "released [Elizabeth I's] subjects from their allegiance to her".[2]

In Ireland the First Desmond Rebellion was launched in 1569, at almost the same time as the Northern Rebellion in England. The Wexford Martyrs were found guilty of high treason for aiding in the escape of James Eustace, 3rd Viscount Baltinglass and refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy and declare Elizabeth I of England to be the Supreme Head of the Church of England and Ireland.

The ongoing religious persecution also became highly significant as the primary cause of the Nine Years War, which formally began when Red Hugh O'Donnell expelled English High Sheriff of Donegal Humphrey Willis, but not before Red Hugh alluded to the recent torture and executions of Archbishop Dermot O'Hurley and Bishop Patrick O'Hely. According to Philip O'Sullivan Beare, "Being surrounded there [Willis] surrendered to Roe by whom he was dismissed in safety with an injunction to remember his words, that the Queen and her officers were dealing unjustly with the Irish; that the Catholic religion was contaminated by impiety; that holy bishops and priests were inhumanely and barbarously tortured; that Catholic noblemen were cruelly imprisoned and ruined; that wrong was deemed right; that he himself had been treacherously and perfidiously kidnapped; and that for these reasons he would neither give tribute or allegiance to the English."[18]

Beatified Martyrs include:

- Patrick O'Hely (Irish: Pádraig Ó hÉilí), Franciscan Bishop of Mayo, executed at Kilmallock 13 August 1579

- Conn O'Rourke (Irish: Conn Ó Ruairc), Franciscan Friar, executed at Kilmallock, 13 August 1579

- 5 Wexford Martyrs, hanged, drawn and quartered in Wexford, 5 July 1581

- Margaret Ball, former Lady Mayoress of Dublin, died 1584 inside Dublin Castle[19]

- Dermot O'Hurley (Irish: Diarmaid Ó hUrthuile), Archbishop of Cashel, hanged outside the walls of Dublin, 20 June 1584

- Muiris Mac Ionrachtaigh (Maurice MacKenraghty), executed at Clonmel, during the Second Desmond Rebellion, 30 April 1585

- Dominic Collins, Jesuit lay brother hanged at Youghal, County Cork, 31 October 1602[20]

Servants of God include:

- Edmund Daniel, SJ, 25 October 1572 in Cork

- Teige O'Daly, OFM, about March 1578 in Limerick

- Donal O'Neylan, OFM, 28 March 1580 in Youghal, Cork

- Gelasius Ó Cuileanáin (born 1554), Cistercian Abbot of Boyle, 21 November 1580 in Dublin

- Eoin O'Mulkern, OPraem, 21 November 1580 in Dublin

- David, John Sutton and Robert Scurlock, laymen, 13 November 1581 in Dublin

- Maurice, Thomas, and Christopher Eustace, laymen, 13 November 1581 in Dublin

- William Wogan and Robert Fitzgerald, laymen, 13 November 1581 in Dublin

- Felim O'Hara, OFM, 1 May 1582 in Moyne, Cork

- Walter Eustace, layman, 14 June 1583 in Dublin

- Richard Creagh (Irish: Risteard Craobhach) (born 1523), Archbishop of Armagh, December 1586 as a prisoner of conscience in the Tower of London, England

King James I[edit]

Beatified Martyrs include:

- Concobhar Ó Duibheannaigh (Conor O'Devany), Franciscan Bishop of Down & Connor, Dublin City, 11 February 1612

- Patrick O'Loughran, priest from County Tyrone and former spiritual director to Aodh Mór Ó Néill, Dublin, 11 February 1612

- Francis Taylor, former Lord Mayor of Dublin, 1621

Servants of God include:

- Brian O'Carolan, priest, 24 March 1606 near Trim, County Meath

- John Burke, layman, 20 December 1606 in Limerick

- Donough MacCready, priest, before 5 August 1608 in Coleraine, County Londonderry

King Charles I[edit]

According to historian D.P. Conyngham, "Ireland was torn by contending factions, and was oppressed by two belligerents during the reign of Charles. The Catholics took up arms in defense of themselves, their religion, and their King. Charles, with the proverbial fickleness of the Stuarts, when pressed by the Puritans, persecuted the Irish, while he encouraged them when he hoped their loyalty and devotion would be the means of establishing his royal prerogative. It is ever thus with Ireland... For eight years Ireland was the theatre of the most desolating war and implacable persecution."[21]

Beatified Martyrs of the era include:

- Fr. Peter O'Higgins, Dominican Order, hanged outside the walls of Dublin at St Stephen's Green, on 24 March 1642[22][23][24]

Servants of God include:

- George Halley (born 1622), OCD, 15 August 1642 in Siddan, County Meath

The Commonwealth and Protectorate of England[edit]

On 24 October 1644, the Puritan-controlled Rump Parliament in London, seeking to retaliate for acts of sectarian violence like the Portadown massacre during the recent 1641 uprising, resolved, "that no quarter shall be given to any Irishman, or to any papist born in Ireland." Upon landing with the New Model Army at Dublin, Oliver Cromwell issued orders that no mercy was to be shown to the Irish, whom he said were to be treated like the Canaanites during the time of the Old Testament prophet Joshua.[25]

According to historian D.P. Conyngham, "It is impossible to estimate the number of Catholics slain the ten years from 1642 to 1652. Three Bishops and more than 300 priests were put to death for their faith. Thousands of men, women, and children were sold as slaves for the West Indies; Sir W. Petty mentions that 6,000 boys and women were thus sold. A letter written in 1656, quoted by Lingard, puts the number at 60,000; as late as 1666 there were 12,000 Irish slaves scattered among the West Indian islands. Forty thousand Irish fled to the Continent, and 20,000 took shelter in the Hebrides or other Scottish islands. In 1641, the population of Ireland was 1,466,000, of whom 1,240,000 were Catholics. In 1659 the population was reduced to 500,091, so that very nearly 1,000,000 must have perished or been driven into exile in the space of eighteen years. In comparison with the population of both periods, this was even worse than the famine extermination of our own days."[26]

After taking the island in 1653, the New Model Army turned Inishbofin, County Galway, into a prison camp for Roman Catholic priests arrested while exercising their religious ministry covertly in other parts of Ireland. The last priests held there were finally released following the Stuart Restoration in 1662.[27]

Officially Beatified Martyrs of the era include:

- Fr. Theobald Stapleton, (Irish: Teabóid Gálldubh), slain during the Sack of Cashel, 15 September 1647.[28]

- Bishop Terence O'Brien of Emly, Dominican Order, hanged at Gallows Green by order of New Model Army General Henry Ireton following the Siege of Limerick, 31 October 1651

- John Kearney, Franciscan Order, hanged at Clonmel, County Tipperary, 21 March 1653[29][30]

- Fr. William Tirry (Irish: Liam Tuiridh), Augustinian Order, hanged at Clonmel, County Tipperary, 12 May 1654

Servants of God include:

Sack of Cashel[edit]

Martyred by the Protestant and Parliamentarian soldiers under the command of the Lord President of Munster, Murchadh na dTóiteán, during the Sack of Cashel

- Edward Stapleton, priest, 13 September 1647,

- Thomas Morissey, priest, 13 September 1647 Sack of Cashel, County Tipperary

- Richard Barry, OP, 13 September 1647, Sack of Cashel, County Tipperary

- Richard Butler and James Saul, OFM, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- William Boyton, SJ, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- Elizabeth Kearney (mother of Blessed John Kearney) and Margaret (surname unrecorded), laywomen, on 13 September 1647

Cromwellian conquest of Ireland[edit]

- Laurence and Bernard O'Ferrall, OP, between February–March 1649 in Longford

- John Bathe, SJ and Thomas Bathe, priest, 11 September 1649, following the Siege of Drogheda, County Louth

- Peter Taafe, OSA,11 September 1649, following the Siege of Drogheda, County Louth

- Dominic Dillon and Richard Oveton, OP, 11 September 1649, following the Siege of Drogheda, County Louth

- Conor MacCarthy, priest, 5 June 1653 in Killarney, County Kerry

- Francis O'Sullivan, OFM, 23 June 1653, Scariff Island, County Kerry

- Thaddeus Moriarty, OP, 15 October 1653 in Killarney, County Kerry

- Donal Breen and James Murphy, priests, 14 April 1655 in Wexford

- Luke Bergin, OP, 14 April 1655 in Wexford

- John Tobin (born 1620), OFMCap, 6 March 1656 in Waterford

Charles II[edit]

During the Stuart Restoration, the Crown's treatment of Catholics was more lenient than usual, owing to the sympathy of the king, until the Popish Plot, a conspiracy theory concocted by Titus Oates and Lord Shaftesbury, who claimed that a plot existed to assassinate the King and massacre all the Protestants of the British Isles. Between 1678 and 1681, the attention of the public was riveted upon a series of anti-Catholic show trials that resulted in 22 executions at Tyburn.

As persecution of Catholics heated up in reaction to the Titus Oates plot, a priest with the Hiberno-Norse surname of Father Mac Aidghalle was murdered while saying the Tridentine Mass at Cloch na hAltorach; a Mass rock that still stands atop Slieve Gullion. The perpetrators were a band of redcoats under the command of a priest hunter named Turner. Local Rapparee leader Count Redmond O'Hanlon is said in local oral tradition to have avenged the murdered priest and in so doing to have sealed his own fate.[31]

Irish victims of the Titus Oates witch hunt included:

- Peter Talbot, Archbishop of Dublin (died imprisoned in Dublin Castle, November 1680)

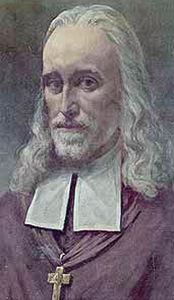

- Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh, executed at Tyburn 1 July 1681

Age of the Whig oligarchy[edit]

Despite their exposure and public disgrace in 1681, the anti-Catholic witch hunt masterminded by Titus Oates and Lord Shaftesbury laid the foundation for the second overthrow of the House of Stuart in 1688, the creation of the anti-Catholic Whig political party, and, despite the best efforts of those who fought in the Jacobite risings, to decades of the British Empire being governed as a Whig single party state.

As the Whig-controlled Parliament of Ireland passed the Penal Laws, which progressively criminalized Roman Catholicism and stripped away from its adherents all rights under the law,[32] a miracle connected to the ongoing religious persecution in Ireland took place, according to Diocesan and municipal records, at Győr in the Kingdom of Hungary.

During the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, a painting of Mary, Comforter of the Afflicted had been removed by Bishop Walter Lynch from Clonfert Cathedral to protect the image from desecration by the New Model Army. Bishop Lynch had kept the image hidden while held in the prison camp at Inishbofin, and, before his death in Hungarian exile, had willed the image to the Cathedral (Hungarian: Mennyekbe Fölvett Boldogságos Szűz Mária székesegyház) of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Győr. On St Patrick's Day 1697, the "Irish Madonna" (Hungarian: Ír Madonna), as she had come to be called, was seen many witnesses to weep tears of blood. The wall and even the canvas behind the image were closely examined and found to be dry. Signed statements remain and bear the signatures of many non-Catholic eyewitnesses, including local Lutheran and Calvinist ministers, the Orthodox Jewish Chief Rabbi of Győr, and Count Siegebert Heister, the Captain General of the town's military garrison.[33] A copy of the image was presented in 2003 to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Clonfert by Bishop Pápai Janos of Győr and now hangs inside St Brendan's Cathedral in Loughrea, County Galway.[34]

A 1709 Penal Act demanded that Catholic priests take the Oath of Abjuration, and recognise the Protestant Queen Anne as Supreme Head of the Church within all her dominions and declare that Catholic doctrine regarding Transubstantiation to be "base and idolatrous".[35]

Priests who refused to take the oath abjuring the Catholic faith were arrested and executed. This activity, along with the compulsory deportation of other priests who did not conform, was a documented attempt to cause the Catholic clergy to die out in Ireland within a generation. Priests had to register with the local magistrates to be allowed to preach, and most did so. Bishops were not permitted to register.[36]

In 1713, the Irish House of Commons declared that "prosecution and informing against Papists was an honourable service", which revived the Elizabethan era profession of priest hunting.[37] The reward rates for capture varied from £50–100 for a bishop, to £10–20 for the capture of an unregistered priest: substantial amounts of money at the time.[36]

Irish nationalist John Mitchel, a Presbyterian from County Londonderry, later wrote, "I know the spots, within my own part of Ireland, where venerable archbishops hid themselves, as it were, in a hole of the rock... Imagine a priest ordained at Seville or Salamanca, a gentleman of a high old name, a man of eloquence and genius, who has sustained disputations in the college halls on a question of literature or theology, and carried off prizes and crowns -- see him on the quays of Brest, bargaining with some skipper to work his passage... And he knows, too, that the end of it all, for him, may be a row of sugar canes to hoe under the blazing sun of Barbados. Yet he pushes eagerly to meet his fate; for he carries in his hands a sacred deposit, bears in his heart a holy message, and he must tell it or die. See him, at last, springing ashore, and hurrying on to seek his Bishop in some cave, or under some hedge -- but going with caution by reason of the priest catcher and the blood-hounds."[38]

- James Dowdall (born 1626), OFMCap, 20 February 1710 in London, England

- Fr. Nicholas Sheehy, Diocesan priest, hanged at Clonmel, County Tipperary, 15 March 1766

First French Republic[edit]

- Fr. Martin Glynn (1729-1794), Roman Catholic priest from Inishbofin, County Galway, last Rector of the Irish College in Bordeaux, and martyr for remaining in the First French Republic and secretly continuing his priestly ministry in nonviolent resistance to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and during the Reign of Terror, guillotined at Bordeaux, 20 July 1794

Canonized Martyrs[edit]

12 October 1975 by Pope Paul VI.

- Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh, 1 July 1681 at Tyburn, London; beatified 1920

The 5 Irish Martyrs of England and Wales[edit]

15 December 1929 by Pope Pius XI.

- John Carey (alias Terence Carey) and Patrick Salmon, laymen, 4 July 1594 at Dorchester, England

- John Cornelius (Irish: Seán Conchobhar Ó Mathghamhna), Jesuit priest, 4 July 1594 at Dorchester, England

- John Roche, layman, 30 August 1588 at Tyburn, England

22 November 1987 by Pope John Paul II.

- Charles Mahoney (alias Meehan), Franciscan, 21 August 1679, Ruthin, Wales

The 17 Blessed Irish Martyrs[edit]

27 September 1992 by Pope John Paul II.

- Patrick O'Hely (Irish: Pádraig Ó hÉilí), Franciscan Bishop of Mayo, betrayed to Lord President of Munster Sir William Drury by the Rebel Earl and Countess of Desmond and executed at Kilmallock 13 August 1579

- Conn O'Rourke (Irish: Conn Ó Ruairc), Franciscan Friar, betrayed to the priest hunters by the Rebel Earl and Countess of Desmond and executed at Kilmallock, 13 August 1579

- Wexford Martyrs, 5 July 1581: Matthew Lambert, Robert Myler, Edward Cheevers, Patrick Cavanagh (Irish: Pádraigh Caomhánach), John O'Lahy, and one other unknown individual

- Margaret Ball, former Lady Mayoress of Dublin, died 1584, as a prisoner of conscience inside Dublin Castle[19]

- Dermot O'Hurley (Irish: Diarmaid Ó hUrthuile), Archbishop of Cashel, sentenced to death by military tribunal and hanged at Lower Baggot Street, then outside the walls of Dublin, 20 June 1584

- Muiris Mac Ionrachtaigh (Maurice MacKenraghty), military chaplain to the Rebel Earl of Desmond, executed at Clonmel, during the Second Desmond Rebellion, 30 April 1585

- Dominic Collins, Jesuit lay brother captured by the Tudor Army following the Siege of Dunboy and executed without trial at Youghal, County Cork, 31 October 1602[20]

- Concobhar Ó Duibheannaigh (Conor O'Devany), Franciscan Bishop of Down & Connor, 11 February 1612

- Patrick O'Loughran, priest from County Tyrone and former spiritual director to Aodh Mór Ó Néill, 11 February 1612

- Francis Taylor, former Lord Mayor of Dublin, died as a prisoner of conscience inside Dublin Castle, 1621

- Peter O'Higgins OP, Prior of the Dominican monastery of Naas, hanged under orders from Sir Charles Coote, despite O'Higgins' well-documented and successful efforts to protect Protestant civilians from sectarian violence and ethnic cleansing during the Irish rebellion of 1641, at St Stephen's Green, then outside the walls of Dublin, on 24 March 1642[22][39][40]

- Theobald Stapleton, (Irish: Teabóid Gálldubh), Roman Catholic priest and one of the creators of modern Irish language orthography. During the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, Fr. Stapleton sought sanctuary inside St. Patrick's Cathedral upon the Rock of Cashel and was slain, alongside six other priests, by the Parliamentary Army of Lord Inchiquin (Irish: Murchadh na dTóiteán) during the Sack of Cashel, 15 September 1647. Fr. Stapleton is said to have blessed his attackers with holy water moments before his death.[28]

- Terence O'Brien OP, Dominican Order, Bishop of Emly, captured following the Siege of Limerick, court martialed, sentenced to death, and hanged by New Model Army General Henry Ireton.[41] Gallows Green, Limerick City, 31 October 1651

- John Kearney, Franciscan Prior of Cashel, hanged at Clonmel, officially for high treason, but in reality for covertly continuing his priestly ministry throughout the valley of the River Suir in nonviolent resistance to the Commonwealth of England's recent decree banishing of all Catholic priests, 21 March 1653[29][30]

- William Tirry (Irish: Liam Tuiridh), Augustinian Friar from St. Austin's Abbey in Cork City, captured by the priest hunters at Fethard, County Tipperary and executed by hanging, officially for high treason against The Protectorate and Commonwealth of England, but in reality for remaining in Ireland and continuing his priestly ministry in nonviolent resistance of the regime's decree of banishment for all priests, at Clonmel, County Tipperary, 12 May 1654

The 42 Martyred Irish Servants of God[edit]

A group of 42 Irish martyrs have been selected for canonisation. This group is composed mostly of priests, both secular and religious as well as several lay men and two lay women. These martyrs have not yet been beatified.

- Edmund Daniel, SJ, 25 October 1572 in Cork

- Teige O'Daly, OFM, about March 1578 in Limerick

- Donal O'Neylan, OFM, 28 March 1580 in Youghal, Cork

- Gelasius Ó Cuileanáin (born 1554), Cistercian Abbot of Boyle, 21 November 1580 in Dublin

- Eoin O'Mulkern, OPraem, 21 November 1580 in Dublin

- David, John Sutton and Robert Scurlock, laymen, 13 November 1581 in Dublin

- Maurice, Thomas, and Christopher Eustace, laymen, 13 November 1581 in Dublin

- William Wogan and Robert Fitzgerald, laymen, 13 November 1581 in Dublin

- Felim O'Hara, OFM, 1 May 1582 in Moyne, Cork

- Walter Eustace, layman, 14 June 1583 in Dublin

- Richard Creagh (Irish: Risteard Craobhach) (born 1523), Archbishop of Armagh, December 1586 as a prisoner of conscience in the Tower of London, England

- Brian O'Carolan, priest, 24 March 1606 near Trim, Meath

- John Burke, layman, 20 December 1606 in Limerick

- Donough MacCready, priest, before 5 August 1608 in Coleraine, Northern Ireland

- George Halley (born 1622), OCD, 15 August 1642 in Siddan, Meath

- Theobald and Edward Stapleton, priests, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- Thomas Morissey, priest, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- Richard Barry, OP, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- Richard Butler and James Saul, OFM, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- William Boyton, SJ, 13 September 1647 in Cashel, Tipperary

- Elizabeth Kearney (mother of Blessed John Kearney) and Margaret (surname unrecorded), laywomen, martyred by the Protestant soldiers under the command of the Lord President of Munster, Murchadh na dTóiteán, during the Sack of Cashel on 13 September 1647

- John Bathe, SJ and Thomas Bathe, priest, 11 September 1649 in Drogheda, Louth

- Peter Taafe, OSA,11 September 1649 in Drogheda, Louth

- Dominic Dillon and Richard Oveton, OP, 11 September 1649 in Drogheda, Louth

- Laurence and Bernard O'Ferrall, OP, between February–March 1649 in Longford

- Conor MacCarthy, priest, 5 June 1653 in Killarney, Kerry

- Francis O'Sullivan, OFM, 23 June 1653 on Scarrrif Island, Kerry

- Thaddeus Moriarty, OP, 15 October 1653 in Killarney, Kerry

- Donal Breen and James Murphy, priests, 14 April 1655 in Wexford

- Luke Bergin, OP, 14 April 1655 in Wexford

Investigations[edit]

Irish martyrs suffered over several reigns. There was a long delay in starting the investigations into the causes of the Irish martrys for fear of reprisals. Further complicating the investigation is that the records of these martyrs were destroyed, or not compiled, due to the danger of keeping such evidence. Details of their endurance in most cases have been lost.[6] The first general catalog is that of Father John Houling, SJ, compiled in Portugal between 1588 and 1599. It is styled a very brief abstract of certain persons whom it commemorates as sufferers for the Faith under Elizabeth.[7]

After Catholic Emancipation in 1829, the cause for Oliver Plunkett was re-visited. As a result, a series of publications on the whole period of persecutions was made. The first to complete the process was Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh, canonized in 1975 by Pope Paul VI.[6] Plunkett was certainly targeted by the administration and unfairly tried.

Biographies[edit]

John Kearney, OFM[edit]

John Kearney (1619-1653) was born in Cashel, County Tipperary and joined the Franciscans at the Kilkenny friary. After his novitiate, he went to Leuven in Belgium and was ordained in Brussels in 1642. Returned to Ireland, he taught in Cashel and Waterford, and was much admired for his preaching. In 1650 he became erenagh of Carrick-on-Suir, County Tipperary. During the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, he was arrested by the New Model Army while continuing to exercise an illegal and underground priestly ministry throughout the valley of the River Suir and executed by hanging at Clonmel, County Tipperary on 21 March 1653. He lies buried in the chapter hall of the suppressed friary of Cashel.[29][30]

Legacy[edit]

Various churches have been dedicated to the martyrs, including:

- Church of the Irish Martyrs, Ballyraine, Letterkenny[19]

- Church of the Irish Martyrs, Ballycane, Naas[42]

- Church of the Irish Martyrs, Cromwell, Otago, New Zealand.

- Church of the Irish Martyrs, Mallee Border Parish, Lameroo, South Australia, Australia

- Chapel of the Irish Martyrs, Pontificio Collegio Irlandese, Pontifical Irish College, Rome, Italy.

See also[edit]

- English Reformation

- List of Catholic martyrs of the English Reformation

- Charles Reynolds (Irish: Cathal Mac Raghnaill) (c. 1496 – 1535), envoy of Silken Thomas to the Holy See who secured a Papal promise to excommunicate Henry VIII over the Act of Supremacy.

References[edit]

- ^ CREAZIONE DI VENTUNO NUOVI BEATI: OMELIA DI GIOVANNI PAOLO II, Piazza San Pietro - Domenica, 27 settembre 1992.

- ^ a b Barry, Patrick, "The Penal Laws", L'Osservatore Romano, p.8, 30 November 1987

- ^ Marcus Tanner (2004), The Last of the Celts, Yale University Press. Pages 227-228.

- ^ Seamus MacManus (1921), The Story of the Irish Race, Barnes & Noble. pp. 462-463.

- ^ R. Dudley Edwards (December 1934), "Venerable John Travers and the Rebellion of Silken Thomas", Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, pp. 687-699.

- ^ a b c "The Irish Martyrs", Irish Jesuits, sacredspace.ie; accessed 16 December 2015.

- ^ a b "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Irish Confessors and Martyrs".

- ^ Hale's History of Pleas of the Crown (1800 ed.) vol. 1, chapter XXIX (from Google Books).

- ^ D.P. Conyngham, Lives of the Irish Martyrs, P.J. Kenedy & Sons, New York. Page 26.

- ^ "Martyrs of England and Wales" New Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9 (1967), p. 322.

- ^ R. Dudley Edwards (December 1934), "Venerable John Travers and the Rebellion of Silken Thomas", Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, pp. 687-699.

- ^ Philip O'Sullivan Beare (1903), Chapters Towards a History of Ireland Under Elizabeth, pages 2-3.

- ^ "Martyrs of England and Wales" New Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9 (1967), p. 322.

- ^ D.P. Conyngham, Lives of the Irish Martyrs, P.J. Kenedy & Sons, New York. Pages 26-27.

- ^ L.P. Murray (1935), "The Franciscan Monasteries after the Dissolution", Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society, Vol. 8, No. 3 (1935), pp. 275-282.

- ^ "The Reign of Elizabeth I" Archived 2017-05-09 at the Wayback Machine by J.P. Sommerville, University of Wisconsin.

- ^ Cusack, Margaret Anne, An Illustrated History of Ireland, libraryireland.com; accessed 11 July 2015.

- ^ Philip O'Sullivan Beare (1903), Chapters Towards a History of Ireland Under Elizabeth, page 68.

- ^ a b c ""The Irish Martyrs", The Church of the Irish Martyrs, Ballyraine". Archived from the original on 2013-09-24. Retrieved 2013-04-13.

- ^ a b "Archives".

- ^ D.P. Conyngham, Lives of the Irish Martyrs, P.J. Kenedy & Sons, New York. Page 137.

- ^ a b "Peter O'Higgins OP". Newbridge College.

- ^ Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin. Pages 148–156.

- ^ Clavin, Terry (October 2009). "Higgins, Peter". In McGuire, James; Quinn, James (eds.). Dictionary of Irish Biography (online ed.). Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ D.P. Conyngham, Lives of the Irish Martyrs, P.J. Kenedy & Sons, New York. Page 138.

- ^ D.P. Conyngham, Lives of the Irish Martyrs, P.J. Kenedy & Sons, New York. Page 138.

- ^ Nugent, Tony (2013). Were You at the Rock? The History of Mass Rocks in Ireland. Liffey Press. Pages 51-52, 148.

- ^ a b "Stapleton, Theobald ('Teabóid Gálldubh') | Dictionary of Irish Biography". www.dib.ie. Retrieved 2022-05-20.

- ^ a b c "Franciscan Saints & Blessed". Archived from the original on 2014-02-04.

- ^ a b c Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin. Pages 165–175.

- ^ Tony Nugent (2013), Were You at the Rock? The History of Mass Rocks in Ireland, pages 80–81.

- ^ Seamus MacManus (1921), The Story of the Irish Race, Barnes & Noble. pp. 454-469.

- ^ Erika Papp Faber (2005), Our Mother's Tears: Ten Weeping Madonnas in Historic Hungary, Academy of the Immaculate. New Bedford, Massachusetts. pp. 44-55, 88-89.

- ^ Hungarian bishop to present 'Irish Madonna' by Patsy McGarry, The Irish Times, Friday October 10, 2003.

- ^ D. P. Conyngham, Lives of the Irish Martyrs, P.J. Kennedy & Sons, New York City. Page 240-241.

- ^ a b MacManus, Seumas (1921). The Story of the Irish Race: A Popular History of Ireland. New York: The Irish Publishing Co.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Tony Nugent (2013), Were You at the Rock? The History of Mass Rocks in Ireland, The Liffey Press. Page 48.

- ^ Seamus MacManus (1921), The Story of the Irish Race, Barnes & Noble. p. 463.

- ^ Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin. Pages 148–156.

- ^ Clavin, Terry (October 2009). "Higgins, Peter". In McGuire, James; Quinn, James (eds.). Dictionary of Irish Biography (online ed.). Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ Terence Albert O'Brien. The Catholic Encyclopedia] Retrieved 28 September 2007.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Naas Parish website". Archived from the original on 2007-11-23. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

Sources[edit]

- Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin.

- New Catholic Dictionary: Irish Martyrs

- O'Reilly, Myles (1880). Lives of the Irish Martyrs and Confessors. New York: James Sheehy. OCLC 173466082.