History of U.S. foreign policy, 1861–1897

The history of U.S. foreign policy from 1861 to 1897 concerns the foreign policy of the United States during the presidential administrations of Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Johnson, Ulysses S. Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, Chester A. Arthur, Grover Cleveland, and Benjamin Harrison. The period began with the outbreak of the American Civil War 1861 and ended with the 1897 inauguration of William McKinley, whose administration commenced a new period of U.S. foreign policy.

During the Civil War, the Lincoln administration succeeded in ensuring that the European powers, including Great Britain and France, did not directly intervene on the side of the Confederacy. Nonetheless, the French defied the Monroe Doctrine and established the Mexican Empire as a puppet state. After the war, pressure from the Johnson administration helped to force the withdrawal of the French and the eventual collapse of the empire. Tensions with Britain escalated as a result of disputes emanating from the Civil War, but the 1871 Treaty of Washington helped restore friendly relations between Britain and the United States. In 1867, Secretary of State William Seward negotiated the Alaska Purchase, thereby acquiring Russian Alaska. The Grant administration negotiated a treaty to annex the Dominican Republic, but it failed to win ratification by the Senate.

Secretary of State James G. Blaine and President Harrison pursued an ambitious trade policy with Latin America, seeking to increase American prosperity and prevent British domination of the region. The U.S. became involved in a protracted dispute with[Germany and Britain over Samoa that ultimately ended with the establishment of a three-power protectorate. President Harrison sought to annex Hawaii during the final months of his tenure, but annexation was rejected during Cleveland's second presidency. After the Cuban War of Independence broke out in 1895, Cleveland announced that the U.S. would remain neutral in the conflict. Cleveland's decisions would later be reversed under President McKinley, leading to a new era of foreign policy during which the U.S. established an overseas empire.

Leadership[edit]

Lincoln administration, 1861–1865[edit]

Republican Abraham Lincoln won election in the 1860 presidential election. The first cabinet position he filled was that of Secretary of State. It was tradition for the president-elect to offer this, the most senior cabinet post, to the leading (best-known and most popular) person of his political party. William Seward was that man and in mid-December 1860, Vice President-elect Hamlin, acting on Lincoln's behalf, offered the position to him.[1] Seward had been deeply disappointed by his failure to win the 1860 Republican presidential nomination, but he agreed to serve as Lincoln's Secretary of State.[2] By the end of 1862, Seward had emerged as the dominant figure in Lincoln's cabinet, though his conservative policies on abolition and other issues annoyed many Republicans. Despite pressure from some congressional leaders to fire Seward, Lincoln retained his Secretary of State for the duration of his presidency.[3]

Seward succeeded in his main goal: to keep Britain and France from recognizing the Confederacy, which counted heavily on them to go to war to protect their supply of cotton. Confederate "King Cotton" diplomacy was a failure—Britain needed American food more than it needed Confederate cotton. Every nation was officially neutral throughout the war, and none formally recognized the Confederacy.

The major nations all recognized that the Confederacy had certain rights as an organized belligerent. A few nations did take advantage of the war. Spain recaptured its lost colony of the Dominican Republic. It lost it again in 1865.[4] More serious was the war by France, under Emperor Napoleon III, to install Maximilian I of Mexico as a puppet ruler, hoping to negate American influence. France, therefore, encouraged Britain to join in a policy of mediation, suggesting that both recognize the Confederacy.[5] Seward repeatedly warned that any recognition of the Confederacy was tantamount to a declaration of war. The British textile industry depended on cotton from the South, but it had stocks to keep the mills operating for a year and in any case, the industrialists and workers carried little weight in British politics. Knowing a war would cut off vital shipments of American food, wreak havoc on the British merchant fleet, and cause the immediate loss of Canada, Britain and its powerful Royal Navy refused to join France.[6]

Historians emphasize that Union diplomacy proved generally effective, with expert diplomats handling numerous crises. British leaders had some sympathy for the Confederacy, but were never willing to risk war with the Union. France was even more sympathetic to the Confederacy, but it was threatened by Prussia and would not make a move without full British cooperation. Confederate diplomats were inept, or as one historian put it, "Poorly chosen diplomats produce poor diplomacy."[7] Other countries played a minor role. Russia made a show of support of the Union, but its importance has often been exaggerated.

Johnson administration, 1865–1869[edit]

Andrew Johnson took office in 1865 after Abraham Lincoln was assassinated during the closing days of the Civil War.[8] On taking office, Johnson promised to continue the policies of his predecessor, and he initially kept Lincoln's cabinet in place. Secretary of State William Seward became one of the most influential members of Johnson's Cabinet, and Johnson allowed Seward to pursue an expansionary foreign policy.[9]

Grant administration, 1869–1877[edit]

Republican Ulysses S. Grant succeeded Johnson following his victory in the 1868 presidential election. Besides Grant himself, the main players in foreign affairs were Secretary of State Hamilton Fish and the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Charles Sumner.[10]

Hayes administration, 1877–1881[edit]

Rutherford Hayes succeeded Grant following his victory in the extremely close and controversial presidential election of 1876. In choosing the members of his cabinet, Hayes spurned Radical Republicans in favor of moderates, and also disregarded anyone whom he considered a potential presidential contender. He chose William M. Evarts, who had defended President Andrew Johnson against impeachment, as Secretary of State. George W. McCrary, who had helped establish the Electoral Commission of 1877, became Secretary of War.[11]

Garfield and Arthur administrations, 1881–1885[edit]

James A. Garfield, a Republican, succeeded Hayes in 1881 after winning the 1880 United States presidential election. James G. Blaine's delegates had provided much of the support for Garfield's nomination at the 1880 Republican National Convention, and the Maine senator received the place of honor: Secretary of State.[12] Blaine, a former protectionist, shared Garfield's opinion on the need to promote freer trade, especially within the Western Hemisphere.[13] Garfield and Blaine formulated several ambitious plans, but they ultimately came to nothing after Garfield was assassinated.[14] Arthur quickly came into conflict with Garfield's cabinet, most of whom represented opposing factions within the party,[15] and Blaine resigned in December 1881.[16] To replace Blaine, the president chose Frederick T. Frelinghuysen of New Jersey, a Stalwart recommended by former President Grant.[16]

First Cleveland administration, 1885–1889[edit]

Democrat Grover Cleveland became president in 1885 after defeating James G. Blaine in the 1884 presidential election. Cleveland faced the challenge of putting together the first Democratic cabinet since the 1850s, and none of the individuals that he appointed to his cabinet had served in the cabinet of another administration. Senator Thomas F. Bayard, Cleveland's strongest rival for the 1884 Democratic nomination, accepted the position of Secretary of State.[17] Cleveland was a committed non-interventionist who had campaigned in opposition to expansion and imperialism. He refused to promote the previous administration's Nicaragua canal treaty, and generally was less of an expansionist in foreign relations than his Republican predecessors.[18] He did, however, see the Monroe Doctrine as an important plank of foreign policy, and he sought to protect American hegemony in the Western Hemisphere.[19]

Harrison administration, 1889–1893[edit]

Republican Benjamin Harrison became president in 1889 after defeating Cleveland in the 1888 presidential election. Blaine and Secretary of State James G. Blaine found common ground on most major policy issues. Blaine played a major role in Harrison's administration,[20] though Harrison made most of the major policy decisions in foreign affairs.[21][22][23] Blaine served in the cabinet until 1892, when he resigned due to poor health and was replaced by John W. Foster.[20] Harrison appreciated the forces of nationalism and imperialism which were inevitably pulling the United States onward into playing a more important part in world affairs as it grew rapidly in financial and economic prowess.[24] The increasing importance of the United States in world affairs was reflected in the act of Congress in 1893 which raised the rank of the most important diplomatic representatives abroad from minister plenipotentiary to ambassador.[21][22][23]

Secretary of State Foster in 1892-1894 actively worked for the annexation of the independent Republic of Hawaii. Pro-American business interests had overthrown the Queen when she rejected constitutional limits on her powers. The new government realize that Hawaii was too small and militarily weak to survive in a world of aggressive imperialism, especially on the part of Japan. It was eager for American annexation.[25] Foster believed Hawaii was vital to American interests in the Pacific. He nearly succeeded, but when Cleveland took office in March 1893, he reversed policy and tried to put the Queen back in power.[26]

Second Cleveland administration, 1893–1897[edit]

Grover Cleveland regained the presidency in 1893 after defeating Harrison in the 1892 presidential election. In assembling his second cabinet, Cleveland avoided re-appointing the cabinet members of his first term. Walter Q. Gresham, a former Republican who had served in President Arthur's cabinet, became Secretary of State. Richard Olney of Massachusetts was initially appointed as Attorney General but succeeded Gresham as Secretary of State after the latter's death.[27]

Foreign policy during the Civil War[edit]

The U.S. and the CSA both recognized the potential importance of foreign powers in the Civil War, as a European intervention could greatly aid the Confederate cause, much as French intervention in the American Revolutionary War had helped the United States gain its independence.[28] At the start of the war, Russia was the lone great power to offer support to the Union, while the other European powers had varying degrees of sympathy for the Confederacy.[29] Nonetheless, all foreign nations were officially neutral throughout the Civil War, and none recognized the Confederacy, marking a major diplomatic achievement for Secretary Seward and the Lincoln Administration.

Although they remained out of the war, the European powers, especially France and Britain, factored into the American Civil War in various ways. European leaders saw the division of the United States as having the potential to eliminate, or at least greatly weaken, a growing rival. They looked for ways to exploit the inability of the U.S. to enforce the Monroe Doctrine. Spain invaded the Dominican Republic in 1861, while France established a puppet regime in Mexico.[30] However, many in Europe also hoped for a quick end to the civil war, for both humanitarian purposes and due to the economic disruption caused by the war.[31]

Lincoln's foreign policy was deficient in 1861 in terms of appealing to European public opinion. The European aristocracy (the dominant factor in every major country) was "absolutely gleeful in pronouncing the American debacle as proof that the entire experiment in popular government had failed." Diplomats had to explain that United States was not committed to the ending of slavery, and instead they repeated legalistic arguments about the unconstitutionality of secession. Confederate spokesmen, on the other hand, were much more successful by ignoring slavery and instead focusing on their struggle for liberty, their commitment to free trade, and the essential role of cotton in the European economy.[32] However, the Confederacy's hope that cotton exports would compel European interference did not come to fruition, as Britain found alternative sources of cotton and experienced economic growth in industries that did not rely on cotton.[33] Though the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation did not immediately end the possibility of European intervention, it rallied European public opinion to the Union by adding abolition as a Northern war goal. Any chance of a European intervention in the war ended with the Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, as European leaders came to believe that the Confederate cause was doomed.[34]

Britain[edit]

Elite opinion in Britain tended to favor the Confederacy, but public opinion tended to favor the United States. Large scale trade continued in both directions with the United States, with the Americans shipping grain to Britain while Britain exported manufactured items and munitions. British trade with the Confederacy was limited, with a trickle of cotton going to Britain and munitions slipped in by numerous small blockade runners.[35][36] The British textile industry depended on cotton from the South, but it had stocks to keep the mills operating for a year and in any case the industrialists and workers carried little weight in British politics.[37] With the announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862, the Civil War became a war against slavery that most British supported.[35]

A serious diplomatic dispute between the U.S. and Great Britain arose late in 1861. The Union Navy intercepted a British mail ship, the Trent, on the high seas and seized two Confederate envoys en route to Europe. The incident aroused public outrage in Britain; the government of Lord Palmerston protested vehemently, while the American public cheered. Lincoln ended the crisis, known as the Trent Affair, by releasing the two diplomats, who had been seized illegally.[38]

British financiers built and operated most of the blockade runners, spending hundreds of millions of pounds on them. They were staffed by sailors and officers on leave from the Royal Navy. When the U.S. Navy captured one of the fast blockade runners, it sold the ship and cargo as prize money for the American sailors, then released the crew. During the war, British blockade runners delivered the Confederacy 60% of its weapons, 1/3 of the lead for its bullets, 3/4 of ingredients for its powder, and most of the cloth for its uniforms;[36] such act lengthened the Civil War by two years and cost 400,000 more lives of soldiers and civilians on both sides.[39]

A British shipyard, John Laird and Sons, built two warships for the Confederacy, including the CSS Alabama, over vehement protests from the United States. The controversy would ultimately be resolved after the Civil War in the form of the Alabama Claims, in which the United States finally was given $15.5 million in arbitration by an international tribunal for damages caused by British-built warships.[40]

France[edit]

Emperor Napoleon III of France sought to re-establish a French empire in North America, with Mexico at the center of an empire that he hoped would eventually include a canal across Central America. In December 1861, France invaded Mexico. While the official justification was the collection of debts, France eventually established a puppet state under the rule of Maximilian I of Mexico. In October 1862, fearing that a re-unified United States would threaten his restored French empire, Napoleon III proposed an armistice and joint mediation of the American Civil War by France, Britain, and Russia. However, this proposal was declined by the other European powers, who feared alienating the North. Napoleon's bellicose stance towards Russia in the 1863 January Uprising divided the powers and greatly diminished any chance of a joint European intervention.[41] The United States refused to recognize Maximilian's government and threatened to drive France out of the country by force, but did not become directly involved in the conflict even as Mexican resistance to Maximilian's rule grew.[42]

Mexico[edit]

Once the Confederacy was defeated, President Johnson and General Grant sent General Phil Sheridan with 50,000 combat veterans to the Texas-Mexico border to emphasize the demand that France withdraw. Johnson provided arms to Juarez, and imposed a naval blockade. In response, Napoleon III informed the Johnson administration that all his troops would be brought home by November 1867. Maximilian was eventually captured and executed in June 1867.[43][44]

Throughout the 1870s, "lawless bands" often crossed the Mexican border on raids into Texas. Three months after taking office, President Hayes granted the Army the power to pursue bandits, even if it required crossing into Mexican territory. Porfirio Díaz, the Mexican president, protested the order and sent troops to the border. The situation calmed as Díaz and Hayes agreed to jointly pursue bandits and Hayes agreed not to allow Mexican revolutionaries to raise armies in the United States.[45] The violence along the border decreased, and in 1880 Hayes revoked the order allowing pursuit into Mexico.[46][47]

Foreign policy of Grant administration, 1869–1877[edit]

Grant was a man of peace, and almost wholly devoted to domestic affairs. There were no foreign-policy disasters, and no wars to engage in. Besides Grant himself, the main players in foreign affairs were Secretary of State Hamilton Fish and the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee Charles Sumner. Historians have high regard for the diplomatic professionalism, independence, and good judgment of Hamilton Fish. The main issues involved Britain, Canada, Santo Domingo, Cuba, and Spain. Worldwide, it was a peaceful era, with no major wars directly affecting the United States. In Europe, Otto von Bismarck was leading Prussia into a dominant position in the new united German Empire. After short, decisive wars with Denmark, Austria and France ended in 1871, Bismarck was the dominant figure in Europe and worked tirelessly and successfully to promote a peaceful continent until his removal in 1890.[48] Grant gave a high priority to protecting and improving the status of Blacks in the United States, and tried to annex the Caribbean country of Dominican Republican as a safety valve for them. Senator Sumner was even more firmly devoted to Black interests and opposed Grant's scheme. Sumner stopped the plan and Grant retaliated by destroying Sumner's power.[49]

Grant's foreign policy was generally successful, except for the attempt to annex Santo Domingo. The annexation of Santo Domingo was Grant's effort to create a haven for blacks in the South and was a first step to end slavery in Cuba and Brazil.[50][51] The dangers of a confrontation with Britain on the Alabama question were resolved peacefully, and to the monetary advantage of the United States. Issues regarding the Canadian boundary were easily settled. The achievements were the work of Secretary Hamilton Fish, who was a spokesman for caution and stability. A poll of historians has stated that Secretary Fish was one of the greatest Secretaries of States in United States history.[52] Fish served as Secretary of State for nearly the entire two terms.

Hamilton Fish (1808 – 1893) was a wealthy New Yorker of Dutch descent who served as Governor of New York (1849 to 1850), and United States Senator (1851 to 1857). Historians emphasize his judiciousness and efforts towards reform and diplomatic moderation.[53][54] Fish settled the controversial Alabama Claims with Britain through his development of the concept of international arbitration.[53] Fish kept the United States out of war with Spain over Cuban independence by coolly handling the volatile Virginius Incident.[53] In 1875, Fish initiated the process that would ultimately lead to Hawaiian statehood, by having negotiated a reciprocal trade treaty for the island nation's sugar production.[53] He also organized a peace conference and treaty in Washington D.C. between South American countries and Spain.[55] Fish worked with James Milton Turner, America's first African American consul, to settle the Liberian-Grebo war.[56] President Grant said he trusted Fish the most for political advice.[57]

Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic)[edit]

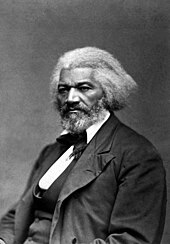

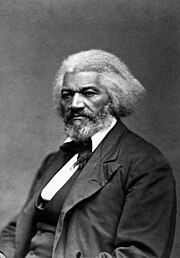

Brady-Handy 1865–1875

In 1869, Grant proposed to annex the independent Spanish-speaking black nation of the Dominican Republic, then known as Santo Domingo. Previously in 1868, President Andrew Johnson had proposed annexation but Congress refused. In July 1869 Grant sent Orville E. Babcock and Rufus Ingalls who negotiated a draft treaty with Dominican Republic president Buenaventura Báez for the annexation of Santo Domingo to the United States and the sale of Samaná Bay for $2 million. To keep the island nation and Báez secure in power, Grant ordered naval ships to secure the island from invasion and internal insurrection. Báez signed an annexation treaty on November 19, 1869. Secretary Fish drew up a final draft of the proposal and offered $1.5 million to the Dominican national debt, the annexation of Santo Domingo as an American state, the United States' acquisition of the rights for Samaná Bay for 50 years with an annual $150,000 rental, and guaranteed protection from foreign intervention. On January 10, 1870, the Santo Domingo treaty was submitted to the Senate for ratification. Despite his support of the annexation, Grant made the mistakes of not building support in Congress or the country at large.[58][59][60]

Not only did Grant believe that the island would be of strategic value to the Navy, particularly Samaná Bay, but also he sought to use it as a bargaining chip. By providing a safe haven for the freedmen, he believed that the exodus of black labor would force Southern whites to realize the necessity of such a significant workforce and accept their civil rights. Grant believed the island country would increase exports and lower the trade deficit. He hoped that U.S. ownership of the island would push Spain to abolish slavery in Cuba and Puerto Rico, and perhaps Brazil as well.[59] On March 15, 1870, the Foreign Relations Committee, headed by Sen. Charles Sumner, recommended against treaty passage. Sumner, the leading spokesman for African American civil rights, believed that annexation would be enormously expensive and involve the U.S. in an ongoing civil war, and would threaten the independence of Haiti and the West Indies, thereby blocking black political progress.[61] On May 31, 1870, Grant went before Congress and urged passage of the Dominican annexation treaty.[59] Strongly opposed to ratification, Sumner successfully led the opposition in the Senate. On June 30, 1870, the Santo Domingo annexation treaty failed to pass the Senate; 28 votes in favor of the treaty and 28 votes against.[62] Grant's own cabinet was divided over the Santo Domingo annexation attempt, and Bancroft Davis, assistant to Sec. Hamilton Fish, was secretly giving information to Sen. Sumner on state department negotiations.[63]

Warren 1879

Grant was determined to keep the Dominican Republic treaty in the public debate, mentioning Dominican Republic annexation in his December 1870 State of the Union Address. Grant was able to get Congress in January 1871 to create a special Commission to investigate the island.[64] Senator Sumner continued to vigorously oppose and speak out against annexation.[64] Grant appointed Frederick Douglass, an African American civil rights activist, as one of the Commissioners who voyaged to the Dominican Republic.[64] Returning to the United States after several months, the Commission in April 1871, issued a report that stated the Dominican people desired annexation and that the island would be beneficial to the United States.[64] To celebrate the Commissions return, Grant invited the Commissioners to the White House, except Frederick Douglass. African American leaders were upset and the issue of Douglass not being invited to the White House dinner was brought up during the 1872 presidential election by Horace Greeley.[65] Douglass, however, who was personally disappointed for not being invited to the White House, remained loyal to Grant and the Republican Party.[65] Although the Commission supported Grant's annexation attempt, there was not enough enthusiasm in Congress to vote on a second annexation treaty.[65]

Unable constitutionally to go directly after Sen. Sumner, Grant immediately removed Sumner's close and respected friend Ambassador, John Lothrop Motley.[66] With Grant's prodding in the Senate, Sumner was finally deposed from the Foreign Relations Committee. Grant reshaped his coalition, known as "New Radicals", working with enemies of Sumner such as Ben Butler of Massachusetts, Roscoe Conkling of New York, and Oliver P. Morton of Indiana, giving in to Fish's demands that Cuba rebels be rejected, and moving his Southern patronage from the radical blacks and carpetbaggers who were allied with Sumner to more moderate Republicans. This set the stage of the Liberal Republican revolt of 1872, when Sumner and his allies publicly denounced Grant and supported Horace Greeley and the Liberal Republicans.[67][68][69][70][59]

A Congressional investigation in June 1870 led by Senator Carl Schurz revealed that Babcock and Ingalls both had land interests in the Bay of Samaná that would increase in value if the Santo Domingo treaty were ratified.[citation needed] U.S. Navy ships, with Grant's authorization, had been sent to protect Báez from an invasion by a Dominican rebel, Gregorio Luperón, while the treaty negotiations were taking place. The investigation had initially been called to settle a dispute between an American businessman Davis Hatch against the United States government. Báez had imprisoned Hatch without trial for his opposition to the Báez government. Hatch had claimed that the United States had failed to protect him from imprisonment. The majority Congressional report dismissed Hatch's claim and exonerated both Babcock and Ingalls. The Hatch incident, however, kept certain Senators from being enthusiastic about ratifying the treaty.[71]

Cuban insurrection[edit]

The Cuban rebellion 1868–1878 against Spanish rule, called by historians the Ten Years' War, gained wide sympathy in the U.S. Juntas based in New York raised money, and smuggled men and munitions to Cuba, while energetically spreading propaganda in American newspapers. The Grant administration turned a blind eye to this violation of American neutrality.[72] In 1869, Grant was urged by popular opinion to support rebels in Cuba with military assistance and to give them U.S. diplomatic recognition. Fish, however, wanted stability and favored the Spanish government, without publicly challenging the popular anti-Spanish American viewpoint. They reassured European governments that the U.S. did not want to annex Cuba. Grant and Fish gave lip service to Cuban independence, called for an end to slavery in Cuba, and quietly opposed American military intervention. Fish, worked diligently against popular pressure, and was able to keep Grant from officially recognizing Cuban independence because it would have endangered negotiations with Britain over the Alabama Claims.[73] Minister to Spain Daniel Sickles failed to get Spain to agree to American mediation. Grant and Fish did not succumb to popular pressures. Grant's message to Congress urged strict neutrality not to officially recognize the Cuban revolt, which eventually petered out.[citation needed]

Treaty of Washington[edit]

Historians have credited the Treaty of Washington for implementing international arbitration to allow outside experts to settle disputes. Grant's able Secretary of State Hamilton Fish had orchestrated many of the events leading up to the treaty. Previously, Secretary of State William H. Seward during the Johnson administration first proposed an initial treaty concerning damages done to American merchants by three Confederate warships, CSS Florida, CSS Alabama, and CSS Shenandoah built in Britain. These damages were collectively known as the Alabama Claims. These ships had inflicted tremendous damage to U.S. shipping, as insurance rates soared and shippers switched to British ships. Washington wanted the British to pay heavy damages, perhaps including turning over Canada.[74] Later, the U.S. added the British blockade runners to the claims, stating that they were responsible for prolonging the war by two years by smuggling in weapons through the Union blockade to the Confederacy.[75][39]

In April 1869, the U.S. Senate overwhelmingly rejected a proposed treaty that paid too little and contained no admission of British guilt for prolonging the war. Senator Charles Sumner spoke up before Congress; publicly denounced Queen Victoria; demanded a huge reparation; and opened the possibility of Canada ceded to the United States as payment. The speech angered the British government, and talks had to be put off until matters cooled down. Negotiations for a new treaty began in January 1871 when Britain sent Sir John Rose to America to meet with Fish. A joint high commission was created on February 9, 1871, in Washington, consisting of representatives from both Britain and the United States. The commission created a treaty where an international Tribunal would settle the damage amounts; the British admitted regret, not fault, over the destructive actions of the Confederate war cruisers nor that charges of blockade running were included in the treaty. Grant approved and signed the treaty on May 8, 1871; the Senate ratified the Treaty of Washington on May 24, 1871.[76][77]

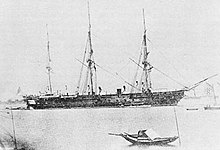

Active service (1862–1864)

The Tribunal met on neutral territory in Geneva, Switzerland. The panel of five international arbitrators included Charles Francis Adams, who was counseled by William M. Evarts, Caleb Cushing, and Morrison R. Waite. On August 25, 1872, the Tribunal awarded United States $15.5 million in gold; $1.9 million was awarded to Great Britain.[78] Historian Amos Elwood Corning noted that the Treaty of Washington and arbitration "bequeathed to the world a priceless legacy".[76] In addition to the $15.5 million arbitration award, the treaty resolved some disputes over borders and fishing rights.[79] On October 21, 1872, William I, Emperor of Germany, settled a boundary dispute in favor of the United States.[78]

Korean incident[edit]

A primary role of the United States Navy in the 19th century was to protect American commercial interests and open trade to Eastern markets, including Japan and China. Korea was a small independent country that excluded all foreign trade. Washington sought a treaty dealing with shipwrecked sailors after the crew of a stranded American commercial ship was executed. The long-term goal for the Grant Administration was to open Korea to Western markets in the same way Commodore Matthew Perry had opened Japan in 1854 by a Naval display of military force. On May 30, 1871, Rear Admiral John Rodgers with a fleet of five ships, part of the Asiatic Squadron, arrived at the mouth of the Salee River below Seoul. The fleet included the Colorado, one of the largest ships in the Navy with 47 guns, 47 officers, and a 571-man crew. While waiting for senior Korean officials to negotiate, Rogers sent ships out to make soundings of the Salee River for navigational purposes.[80][81]

The American fleet was fired upon by a Korean fort, but there was little damage. Rogers gave the Korean government ten days to apologize or begin talks, but the Royal Court kept silent. After ten days passed, on June 10, Rogers began a series of amphibious assaults that destroyed 5 Korean forts. These military engagements were known as the Battle of Ganghwa. Several hundred Korean soldiers and three Americans were killed. Korea still refused to negotiate, and the American fleet sailed away. The Koreans refer to this 1871 U.S. military action as Shinmiyangyo. Grant defended Rogers in his third annual message to Congress in December 1871. After a change in regimes in Seoul, in 1881, the U.S. negotiated a treaty – the first treaty between Korea and a Western nation.[80]

Alaska purchase[edit]

An expansionist, Secretary of State Seward sought opportunities to gain territory for the United States during Johnson's presidency. In 1867, he negotiated a treaty with Denmark to purchase the Danish West Indies for $7.5 million, but the Senate refused to ratify it.[82] Seward also proposed to acquire British Columbia as a trade-off against the Alabama Claims, but the British were uninterested in this proposal.[83][84]

By 1867, the Russian government saw its North American colony (today Alaska) as a financial liability, and feared eventually losing it if a war broke out with Britain. Russian minister Eduard de Stoeckl was instructed to sell Alaska to the United States, and did so deftly, convincing Seward to raise his initial offer from $5 million to $7.2 million.[85] This sum is the inflation-adjusted equivalent to $157 million in present-day terms.[86] On March 30, 1867, de Stoeckl and Seward signed the treaty, and President Johnson summoned the Senate into session and it approved the Alaska Purchase in 37–2 vote.[87] Although ridiculed in some quarters as "Seward's Folly," American public opinion was generally quite favorable in terms of the potential for economic benefits at a bargain price, maintaining the friendship of Russia. and blocking British expansion.[88]

Failed annexation of Dominican Republic[edit]

Brady-Handy 1865–1875

In 1869, Grant proposed to annex the independent Spanish-speaking black nation of the Dominican Republic, then known as Santo Domingo. Previously in 1868, President Andrew Johnson had proposed annexation but Congress refused. In July 1869 Grant sent Orville E. Babcock and Rufus Ingalls who negotiated a draft treaty with Dominican Republic President Buenaventura Báez. To keep the island nation and Báez secure in power, Grant ordered naval ships to secure the island from invasion and internal insurrection. Báez signed an annexation treaty on November 19, 1869. Secretary Fish drew up a final draft of the proposal and offered $1.5 million to the Dominican national debt, the annexation of Santo Domingo as an American state, the United States' acquisition of the rights for Samaná Bay for 50 years with an annual $150,000 rental, and guaranteed protection from foreign intervention. On January 10, 1870, the Santo Domingo treaty was submitted to the Senate for ratification. Despite his support of the annexation, Grant made the mistakes of not building support in Congress or the country at large. [58][89][60]

Not only did Grant believe that the island would be of strategic value to the Navy, but also he sought to use it as a domestic bargaining chip. By providing a safe haven for the freedmen, he believed that the threatened exodus of black labor would force Southern whites to realize the necessity of such a significant workforce and accept their civil rights. Furthermore, Grant believed the island country would increase exports and lower the trade deficit. He hoped that U.S. ownership of the island would push Spain to abolish slavery in Cuba and Puerto Rico. [89] On March 15, 1870, the Foreign Relations Committee, headed by Sen. Charles Sumner, recommended against treaty passage. Sumner, the leading spokesman for African American civil rights, believed that annexation would be enormously expensive and involve the U.S. in an ongoing civil war, and would threaten the independence of Haiti and the West Indies, thereby blocking black political progress.[61] On May 31, 1870, Grant went before Congress and urged passage of the Dominican annexation treaty.[59] Sumner successfully led the opposition in the Senate. On June 30, 1870, the Santo Domingo annexation treaty failed to pass the Senate; 28 votes in favor of the treaty and 28 votes against.[62] Grant's own cabinet was divided over the Santo Domingo annexation attempt, and Bancroft Davis, assistant to Sec. Hamilton Fish, was secretly giving information to Sumner on State Department negotiations.[63]

Warren 1879

Grant was determined to keep the Dominican Republic treaty in the public debate, mentioning annexation in his December 1870 State of the Union Address. Grant was able to get Congress in January 1871 to create a special Commission to investigate the island.[64] Senator Sumner continued to vigorously oppose annexation.[64] Grant appointed Frederick Douglass, an African American civil rights activist, as one of the Commissioners sent to the island.[64] The Commission in April 1871 issued a report that stated the Dominican people desired annexation and that the island would be beneficial to the United States.[64] Although the Commission supported Grant's annexation attempt, there was not enough enthusiasm in Congress to vote on a second annexation treaty.[65]

Unable constitutionally to go directly after Sen. Sumner, Grant immediately removed Sumner's close and respected friend Ambassador, John Lothrop Motley.[90] With Grant's prodding in the Senate, Sumner was finally deposed from the Foreign Relations Committee.[67][68][91][89]

A Congressional investigation in June 1870 led by Senator Carl Schurz revealed that Babcock and Ingalls both had land interests in the Bay of Samaná that would increase in value if the Santo Domingo treaty were ratified.[citation needed] U.S. Navy ships, with Grant's authorization, had been sent to protect Báez from an invasion by a Dominican rebel, Gregorio Luperón, while the treaty negotiations were taking place. The investigation had initially been called to settle a dispute between an American businessman Davis Hatch against the United States government. Báez had imprisoned Hatch without trial for his opposition to the Báez government. Hatch had claimed that the United States had failed to protect him from imprisonment. The majority Congressional report dismissed Hatch's claim and exonerated both Babcock and Ingalls. The Hatch incident, however, kept certain Senators from being enthusiastic about ratifying the treaty.[92]

Relations with Britain[edit]

Fenian raids[edit]

The Fenians, a secret Irish Catholic militant organization, recruited heavily among Civil War veterans in preparation to invade Canada. The group's goal was to force Britain to grant Ireland its independence. The Fenians counted thousands of members, but they had a confused command structure, competing factions, unfamiliar new weapons, and British agents in their ranks who alerted the Canadians. Their invasion forces were too small and had poor leadership. Several attempts were organized, but they were either canceled at the last minute or failed in a matter of hours. The largest raid took place on May 31-June 2, 1866, when about 1000 Fenians crossed the Niagara River. The Canadians were forewarned, and over 20,000 Canadian militia and British regulars turned out. A few men on each side were killed and the Fenians soon retreated home.[93] The Johnson administration at first quietly tolerated this violation of American neutrality, but, by 1867, dispatched the U.S. Army to prevent further Fenian raids. The Fenians organized a second attack on May 25, 1870, but it was broken up by the United States Marshal for Vermont. London realized that American tolerance for the Fenians showed the strong U.S. displeasure with the British record during the Civil War, and hastened to resolve the Alabama Claims issue. In the long run, the Fenians gave no help to independence movements in Ireland, but they did stimulate a new sense of Canadian nationalism.[94]

Treaty of Washington[edit]

Historians have credited the Treaty of Washington for implementing international arbitration to allow outside experts to settle disputes. Grant's able Secretary of State Hamilton Fish had orchestrated many of the events leading up to the treaty. Previously, Secretary of State William H. Seward during the Johnson administration first proposed an initial treaty concerning damages done to American merchants by three Confederate warships, CSS Florida, CSS Alabama, and CSS Shenandoah built in Britain. These damages were collectively known as the Alabama Claims. These ships had inflicted tremendous damage to U.S. shipping, as insurance rates soared and shippers switched to British ships. Washington wanted the British to pay heavy damages, perhaps including turning over Canada.[95]

Active service (1862–1864)

In April 1869, the U.S. Senate overwhelmingly rejected a proposed treaty which paid too little and contained no admission of British guilt for prolonging the war. Senator Charles Sumner spoke up before Congress; publicly denounced Queen Victoria; demanded a huge reparation; and opened the possibility of Canada ceded to the United States as payment. The speech angered the British government, and talks had to be put off until matters cooled down. Negotiations for a new treaty began in January 1871 when Britain sent Sir John Rose to America to meet with Fish. A joint high commission was created on February 9, 1871, in Washington, consisting of representatives from both Britain and the United States. The commission created a treaty where an international Tribunal would settle the damage amounts; the British admitted regret, not fault, over the destructive actions of the Confederate war cruisers. Grant approved and signed the treaty on May 8, 1871; the Senate ratified the Treaty of Washington on May 24, 1871.[76][77] The Tribunal met on neutral territory in Geneva, Switzerland. The panel of five international arbitrators included Charles Francis Adams, who was counseled by William M. Evarts, Caleb Cushing, and Morrison R. Waite. On August 25, 1872, the Tribunal awarded United States $15.5 million in gold; $1.9 million was awarded to Great Britain.[78] Historian Amos Elwood Corning noted that the Treaty of Washington and arbitration "bequeathed to the world a priceless legacy".[76] On October 21, 1872, William I, Emperor of Germany, settled a boundary dispute in favor of the United States.[78]

Aleutian Islands[edit]

The first problem Harrison faced arose from disputed fishing rights on the Alaskan coast. After Canada claimed fishing and sealing rights around many of the Aleutian Islands, the U.S. Navy seized several Canadian ships. In 1891, the administration began negotiations with the British that led to a compromise over fishing rights after international arbitration, with the British government paying compensation in 1898.[96]

Population flows to and from Canada[edit]

After 1850, the pace of industrialization and urbanization was much faster in the United States, drawing a wide range of immigrants from the North. By 1870, 1/6 of all the people born in Canada had moved to the United States, with the highest concentrations in New England, which was the destination of Francophone emigrants from Quebec and Anglophone emigrants from the Maritimes. It was common for people to move back and forth across the border, such as seasonal lumberjacks, entrepreneurs looking for larger markets, and families looking for jobs in the textile mills that paid much higher wages than in Canada.[97]

The southward migration slacked off after 1890, as Canadian industry began a growth spurt. By then, the American frontier was closing, and thousands of farmers looking for fresh land moved from the United States north into the Prairie Provinces. The net result of the flows were that in 1901 there were 128,000 American-born residents in Canada (3.5% of the Canadian population) and 1.18 million Canadian-born residents in the United States (1.6% of the U.S. population).[98]

Cuba and Spain[edit]

Ten Years' War[edit]

The Cuban rebellion 1868–1878 against Spanish rule, called by historians the Ten Years' War, gained wide sympathy in the U.S. Juntas based in New York raised money, and smuggled men and munitions to Cuba, while energetically spreading propaganda in American newspapers. The Grant administration turned a blind eye to this violation of American neutrality.[99] In 1869, Grant was urged by popular opinion to support rebels in Cuba with military assistance and to give them U.S. diplomatic recognition. Fish, however, wanted stability and favored the Spanish government, without publicly challenging the popular anti-Spanish American viewpoint. They reassured European governments that the U.S. did not want to annex Cuba. Grant and Fish gave lip service to Cuban independence, called for an end to slavery in Cuba, and quietly opposed American military intervention. Fish, worked diligently against popular pressure, and was able to keep Grant from officially recognizing Cuban independence because it would have endangered negotiations with Britain over the Alabama Claims.[100] Minister to Spain Daniel Sickles failed to get Spain to agree to American mediation. Grant and Fish did not succumb to popular pressures. Grant's message to Congress urged strict neutrality not to officially recognize the Cuban revolt, which eventually petered out.[citation needed]

Virginus incident[edit]

On October 31, 1873, a steamer Virginius, flying the American flag carrying war materials and men to aid the Cuban insurrection (in violation of American and Spanish law) was intercepted and taken to Cuba. After a hasty trial, the local Spanish officials executed 53 would-be insurgents, eight of whom were United States citizens; orders from Madrid to delay the executions arrived too late. War scares erupted in both the U.S. and Spain, heightened by the bellicose dispatches from the American minister in Madrid, retired general Daniel Sickles. Secretary of State Fish kept a cool demeanor in the crisis, and through investigation discovered there was a question over whether the Virginius ship had the right to bear the United States flag. The Spanish Republic's President Emilio Castelar expressed profound regret for the tragedy and was willing to make reparations through arbitration. Fish negotiated reparations with the Spanish minister Senor Poly y Bernabe. With Grant's approval, Spain was to surrender Virginius, pay an indemnity to the surviving families of the Americans executed, and salute the American flag; the episode ended quietly.[101]

Cuban War of Independence[edit]

The Cuban War of Independence began late in 1895 as Cuban rebels sought to break free from Spanish rule. The United States and Cuba enjoyed close trade relations, and humanitarian concerns led many Americans to demand intervention on the side of the rebels. Cleveland did not sympathize with the rebel cause and feared that an independent Cuba would ultimately fall to another European power. He issued a proclamation of neutrality in June 1895 and warned that he would stop any attempted intervention by American adventurers.[102]

Immigration from China[edit]

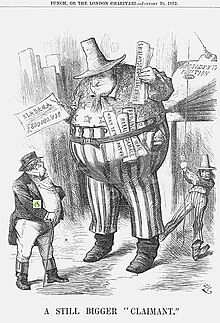

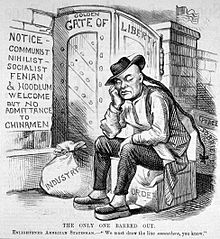

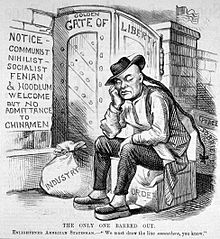

In 1868, the Senate ratified the Burlingame Treaty with China, allowing an unrestricted flow of Chinese immigrants into the country. As the economy soured after the Panic of 1873, Chinese immigrants were blamed for depressing workmen's wages.[103] During the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, anti-Chinese riots broke out in San Francisco, and a third party, the Workingman's Party, was formed with an emphasis on stopping Chinese immigration.[103] In response, Congress passed a measure, the "Fifteen Passenger Bill" in 1879, aimed at limiting the number of Chinese passengers permitted on vessels arriving at U.S. ports.[104] As the legislation would violate the terms of the Burlingame Treaty, President Hayes vetoed it,[105] drawing praise among eastern liberals but bitter denunciation in the West.[105] In the subsequent furor, Democrats in the House of Representatives attempted to impeach Hayes, but narrowly failed when Republicans prevented a quorum by refusing to vote.[106] After the veto, Assistant Secretary of State Frederick W. Seward and James Burrill Angell negotiated with the Chinese to reduce the number of Chinese immigrants.[106] The resulting accord, the Angell Treaty of 1880, allowed the U.S. to suspend Chinese immigration.[104][106]

When President Arthur took office, there were 250,000 Chinese immigrants in the United States, most of whom lived in California and worked as farmers or laborers.[107] Senator John F. Miller of California introduced another Chinese Exclusion Act that denied Chinese immigrants United States citizenship and banned their immigration for a twenty-year period.[108] Miller's bill passed the Senate and House by overwhelming margins, but Arthur vetoed the bill, as he believed that the twenty-year ban breached the Angell Treaty, which allowed only a "reasonable" suspension of immigration. Eastern newspapers praised the veto, but it was condemned in the Western states. Congress was unable to override the veto, but passed a new bill reducing the immigration ban to ten years. Although he still objected to this denial of citizenship to Chinese immigrants, Arthur acceded to the compromise measure, signing the Chinese Exclusion Act into law on May 6, 1882.[108] Secretary of State Bayard later negotiated an extension to the Chinese Exclusion Act, and Cleveland lobbied the Congress to pass the Scott Act, written by Congressman William Lawrence Scott, which prevented the return of Chinese immigrants who left the United States. The Scott Act easily passed both houses of Congress, and Cleveland signed it into law in October 1888.[109]

Peacemaking and arbitration[edit]

In 1878, following the Paraguayan War, President Hayes arbitrated a territorial dispute between Argentina and Paraguay.[110] Hayes awarded the disputed land in the Gran Chaco region to Paraguay, and the Paraguayans honored him by renaming a city (Villa Hayes) and a department as (Presidente Hayes) in his honor.[110]

Secretary of State Blaine sought to negotiate a peace in the War of the Pacific, then being fought by Bolivia, Chile, and Peru.[111] Blaine favored a resolution that would not result in Peru yielding any territory, but Chile, which by 1881 had occupied the Peruvian capital, Lima, rejected any settlement that restored the previous status quo.[112] In October 1883, the War of the Pacific was settled without American involvement, with the Treaty of Ancón.

When Britain and Venezuela disagreed over the boundary between Venezuela and the colony of British Guiana, President Cleveland and Secretary of State Olney protested.[113] The British initially rejected the U.S. demand for an arbitration of the boundary dispute and rejected the validity and relevance of the Monroe Doctrine.[114] Ultimately, British Prime Minister Lord Salisbury decided that dispute over the boundary with Venezuela was not worth antagonizing the United States, and the British assented to arbitration.[115] A tribunal convened in Paris in 1898 to decide the matter, and in 1899 awarded the bulk of the disputed territory to British Guiana.[116] Seeking to extend arbitration to all disputes between the two countries, the United States and Britain agreed to the Olney–Pauncefote Treaty in 1897, but the treaty fell three votes short of ratification in the Senate.[117]

Trade agreements[edit]

President Garfield and Secretary of State Blaine sought to increase trade with Latin America in order to increase American prosperity and prevent Great Britain from dominating the region.[13] Garfield authorized Blaine to call for a Pan-American conference in 1882 to mediate disputes among the Latin American nations and to serve as a forum for talks on increasing trade.[111] Though efforts to organize the conference ended after Garfield's death and Blaine's subsequent resignation, Arthur and Frelinghuysen continued Blaine's efforts to encourage trade among the nations of the Western Hemisphere. A treaty with Mexico providing for reciprocal tariff reductions was signed in 1882 and approved by the Senate in 1884,[118] but legislation required to bring the treaty into force failed in the House.[118] Similar efforts at reciprocal trade treaties with Santo Domingo and Spain's American colonies were defeated by February 1885, and an existing reciprocity treaty with the Kingdom of Hawaii was allowed to lapse.[119] The Frelinghuysen-Zavala Treaty, which would have allowed the United States to build a canal connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans via Nicaragua, was also defeated in the Senate.[120]

Blaine returned as Secretary of State under President Harrison in 1889, Blaine and Harrison pursued ambitious foreign policy that emphasized commercial reciprocity with other nations.[121] The First International Conference of American States met in Washington in 1889; Harrison set an aggressive agenda including customs and currency integration and named a bipartisan conference delegation led by John B. Henderson and Andrew Carnegie. Though the conference failed to achieve any diplomatic breakthrough, it did succeed in establishing an information center that became the Pan American Union.[122]

In response to the diplomatic bust, Harrison and Blaine pivoted diplomatically and initiated a crusade for tariff reciprocity with Latin American nations; the Harrison administration concluded eight reciprocity treaties among these countries.[123] The Harrison administration did not pursue reciprocity with Canada, as Harrison and Blaine believed that Canada was an integral part of the British economic bloc and could never be integrated into a trade system dominated by the U.S.[124] On another front, Harrison sent Frederick Douglass as ambassador to Haiti, but failed in his attempts to establish a naval base there.[125] There were a few minor trade squabbles with other countries, usually handled quietly by the diplomats.[126]

Military modernization and build-up[edit]

In the years following the Civil War, American naval power declined precipitously, shrinking from nearly 700 vessels to just 52, most of which were obsolete.[127] Garfield's Secretary of the Navy, William H. Hunt, had advocated reform of the Navy and his successor, William E. Chandler, appointed an advisory board to prepare a report on modernization.[128] Based on the suggestions in the report, Congress appropriated funds for the construction of three steel protected cruisers (Atlanta, Boston, and Chicago) and an armed dispatch-steamer (Dolphin), collectively known as the ABCD Ships or the Squadron of Evolution.[129] Congress also approved funds to rebuild four monitors (Puritan, Amphitrite, Monadnock, and Terror), which had lain uncompleted since 1877.[129] Arthur strongly supported these efforts, believing that a strengthened navy would not only increase the country's security but also enhance U.S. prestige.[130] The contracts to build the ABCD ships were all awarded to the low bidder, John Roach & Sons of Chester, Pennsylvania,[131] even though Roach once employed Secretary Chandler as a lobbyist.[131] Democrats turned against the "New Navy" projects and, when they won control of the 48th Congress, refused to appropriate funds for seven more steel warships.[131] Even without the additional ships, the state of the Navy improved when, after several construction delays, the last of the new ships entered service in 1889.[132]

Under President Cleveland, Secretary of the Navy Whitney promoted the modernization of the Navy, although no ships were constructed that could match the best European warships. Construction of four steel-hulled warships that had begun under the Arthur administration was delayed due to a corruption investigation and subsequent bankruptcy of their building yard, but these ships were completed in a timely manner once the investigation was over.[133] Sixteen additional steel-hulled warships were ordered by the end of 1888; these ships later proved vital in the Spanish–American War of 1898, and many served in World War I. These ships included the "second-class battleships" Maine and Texas, which were designed to match modern armored ships recently acquired by South American countries from Europe. Eleven protected cruisers (including Olympia), one armored cruiser, and one monitor were also ordered, along with the experimental cruiser Vesuvius.[134]

The second Cleveland administration was as committed to military modernization as the first, and ordered the first ships of a navy capable of offensive action. The adoption of the Krag–Jørgensen rifle, the U.S. Army's first bolt-action repeating rifle, was finalized.[135][136] In 1895–96 Secretary of the Navy Hilary A. Herbert, having recently adopted the aggressive naval strategy advocated by Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, successfully proposed ordering five battleships (the Kearsarge and Illinois classes) and sixteen torpedo boats.[137][138] Completion of these ships nearly doubled the Navy's battleships and created a new torpedo boat force, which previously had consisted of only two boats.[139]

Samoa[edit]

Cleveland's first term saw the start of the Samoan crisis between the U.S., Germany, and Great Britain.[140] Each of those nations had signed a treaty with Samoa under which they were allowed to engage in trade and maintain a naval base, but Cleveland feared that the Germans sought to annex Samoa after the Germans attempted to remove Malietoa Laupepa as the monarch of Samoa in favor of Tuiātua Tupua Tamasese Titimaea. The U.S. encouraged another claimant to the throne, Mata'afa Iosefo, to rebel against Malietoa, and in doing so Mata'afa's forces killed a contingent of German naval guards.[141]

By 1889, the United States, Great Britain and Germany were locked in an escalating dispute over control of the Samoan Islands in the Pacific.[142] Seeking to improve relations with Britain and the United States, German Chancellor Otto Von Bismarck convened a conference in Berlin to settle the matter. Delegates from the three countries agreed to the Treaty of Berlin, which established a three-power protectorate in Samoa. Historian George H. Ryden argues that Harrison played a key role in determining the status of this Pacific outpost by taking a firm stand on every aspect of Samoa conference negotiations; this included selection of the local ruler, refusal to allow an indemnity for Germany, as well as the establishment of the three-power protectorate, a first for the U.S.[143][144] A serious long-term result was an American distrust of Germany's foreign policy after Bismarck was forced out in 1890.[145][146]

Hawaii[edit]

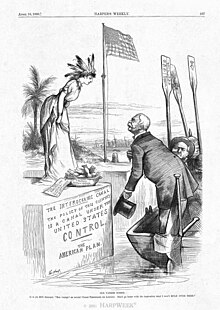

In December 1874, Grant held a state dinner at the White House for the King of Hawaii, Kalākaua, who was seeking the export of Hawaiian sugar duty-free to the United States. Grant and Fish were able to produce a successful free trade treaty in 1875 with the Hawaiian Kingdom, incorporating the Pacific islands' sugar industry into the United States' economy sphere.[147]

President Harrison sought to annex the kingdom, which held a strategic position in the Pacific Ocean,[148] and hosted a growing sugar business controlled by American settlers.[149][150][151] Following a coup d'état against Queen Liliuokalani, the new government of Hawaii led by Sanford Dole petitioned for annexation by the United States.[152] Harrison was interested in expanding American influence in Hawaii and in establishing a naval base at Pearl Harbor, but had not previously expressed an opinion on annexing the islands.[153] The United States consul in Hawaii recognized the new Hawaiian government on February 1, 1893, and forwarded their proposal of annexation to Washington. With just one month left before leaving office, the administration signed the annexation treaty on February 14 and submitted it to the Senate the next day.[152] The Senate failed to act, and President Cleveland withdrew the treaty shortly after taking office later that year.[154]

In the intervening four years, Honolulu businessmen of European and American ancestry had denounced Queen Liliuokalani as a tyrant who rejected constitutional government. In early 1893, they overthrew her, set up a republican government under Sanford B. Dole, and sought to join the United States.[155] The Harrison administration had quickly agreed with representatives of the new government on a treaty of annexation and submitted it to the Senate for approval.[155] Five days after taking office on March 9, 1893, Cleveland withdrew the treaty from the Senate. His biographer Alyn Brodsky argues it was a deeply personal opposition on Cleveland's part to what he saw as an immoral action against a little kingdom:

- Just as he stood up for the Samoan Islands against Germany because he opposed the conquest of a lesser state by a greater one, so did he stand up for the Hawaiian Islands against his own nation. He could have let the annexation of Hawaii move inexorably to its inevitable culmination. But he opted for confrontation, which he hated, as it was to him the only way a weak and defenseless people might retain their independence. It was not the idea of annexation that Grover Cleveland opposed, but the idea of annexation as a pretext for illicit territorial acquisition.[156]

Cleveland sent former Congressman James Henderson Blount to Hawai'i to investigate the conditions there. Blount, a leader in the white supremacy movement in Georgia, had long denounced imperialism. Some observers speculated he would support annexation on grounds of the inability of Asiatics to govern themselves. Instead, Blount proposed that the U.S. military restore the Queen by force and argued that the Hawaiian natives should be allowed to continue their "Asiatic ways."[157] Cleveland decided to restore the queen, but she refused to grant amnesty as a condition of her reinstatement, saying that she would either execute or banish the current government in Honolulu, and seize all of their properties. Dole's government refused to yield their position, and few Americans wanted to use armed force to overthrow a republican government in order to install an absolute monarch. In December 1893, Cleveland referred the issue to Congress; he encouraged the continuation of the American tradition of non-intervention. Dole had more support in Congress than the queen.[158] Republicans warned that a completely independent Hawaii could not long survive the scramble for colonies. Most observers thought Japan would soon take it over, and indeed the population of Hawaii was already over 20 percent Japanese. The Japanese advance was worrisome especially on the West Coast.[159] The Senate, under Democratic control but opposed to Cleveland, commissioned the Morgan Report, which contradicted Blount's findings and found the overthrow was a completely internal affair.[160] Cleveland dropped all talk of reinstating the queen, and went on to recognize and maintain diplomatic relations with the new Republic of Hawaii. In 1898, after Cleveland left office, the United States annexed Hawaii.[161]

Other crises and incidents, 1865–1897[edit]

Panamanian Canal[edit]

Hayes was perturbed over the plans of Ferdinand de Lesseps, the builder of the Suez Canal, to construct a canal across the Isthmus of Panama, which was then owned by Colombia. Concerned about a repetition of French adventurism in Mexico, Hayes interpreted the Monroe Doctrine firmly. In a message to Congress, Hayes explained his opinion on the canal: "The policy of this country is a canal under American control ... The United States cannot consent to the surrender of this control to any European power or any combination of European powers."[162]

Korean incident[edit]

A primary role of the United States Navy in the 19th century was to protect American commercial interests and open trade to Eastern markets, including Japan and China. Korea was a small independent country that excluded all foreign trade. Washington sought a treaty dealing with shipwrecked sailors after the crew of a stranded American commercial ship was executed. The long-term goal for the Grant Administration was to open Korea to Western markets in the same way Commodore Matthew Perry had opened Japan in 1854 by a Naval display of military force. On May 30, 1871, Rear Admiral John Rodgers with a fleet of five ships, part of the Asiatic Squadron, arrived at the mouth of the Salee River below Seoul. The fleet included the Colorado, one of the largest ships in the Navy with 47 guns, 47 officers, and a 571-man crew. While waiting for senior Korean officials to negotiate, Rogers sent ships out to make soundings of the Salee River for navigational purposes.[80][163][incomplete short citation][page needed]

The American fleet was fired upon by a Korean fort, but there was little damage. Rogers gave the Korean government ten days to apologize or begin talks, but the Royal Court kept silent. After ten days passed, on June 10, Rogers began a series of amphibious assaults that destroyed 5 Korean forts. These military engagements were known as the Battle of Ganghwa. Several hundred Korean soldiers and three Americans were killed. Korea still refused to negotiate, and the American fleet sailed away. The Koreans refer to this 1871 U.S. military action as Shinmiyangyo. Grant defended Rogers in his third annual message to Congress in December 1871. After a change in regimes in Seoul, in 1881, the U.S. negotiated a treaty – the first treaty between Korea and a Western nation.[80]

European embargo of U.S. pork[edit]

In response to vague reports of trichinosis that supposedly originated with American hogs, Germany and nine other European countries imposed a ban on importation of United States pork in the 1880s.[164] At issue was over 1.3 billion pounds of pork products in 1880 with a value of $100 million annually.[165][166] Harrison persuaded Congress to enact the Meat Inspection Act of 1890 to guarantee the quality of the export product, and ordered Agriculture Secretary Jeremiah McLain Rusk to threaten Germany with retaliation by initiating an embargo against Germany's popular beet sugar. That proved decisive, and in September 1891 Germany relented; other nations soon followed.[167][168]

Baltimore Crisis[edit]

In 1891, a new diplomatic crisis, known as the Baltimore Crisis, emerged in Chile. The American minister to Chile, Patrick Egan, granted asylum to Chileans who were seeking refuge during the 1891 Chilean Civil War. Egan, previously a militant Irish immigrant to the U.S., was motivated by a personal desire to thwart Great Britain's influence in Chile.[169] The crisis began in earnest when sailors from the USS Baltimore took shore leave in Valparaiso and a fight ensued, resulting in the deaths of two American sailors and the arrest of three dozen others.[170] The Baltimore's captain, Winfield Schley, based on the nature of the sailors' wounds, insisted the sailors had been bayonet-attacked by Chilean police without provocation. With Blaine incapacitated, Harrison drafted a demand for reparations.[171] The Chilean Minister of Foreign Affairs replied that Harrison's message was "erroneous or deliberately incorrect," and said that the Chilean government was treating the affair the same as any other criminal matter.[171]

Tensions increased to the brink of war – Harrison threatened to break off diplomatic relations unless the United States received a suitable apology, and said the situation required "grave and patriotic consideration". The president also remarked, "If the dignity as well as the prestige and influence of the United States are not to be wholly sacrificed, we must protect those who in foreign ports display the flag or wear the colors."[172] A recuperated Blaine made brief conciliatory overtures to the Chilean government which had no support in the administration; he then reversed course and joined the chorus for unconditional concessions and apology by the Chileans. The Chileans ultimately obliged, and war was averted. Theodore Roosevelt later applauded Harrison for his use of the "big stick" in the matter.[173][174]

References[edit]

- ^ Stahr (2012) pp. 214-217.

- ^ Paludan (1993), pp. 37–38

- ^ Paludan (1993), pp. 169–176

- ^ James W. Cortada, "Spain and the American Civil War: Relations at Mid-century, 1855–1868." Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 70.4 (1980): 1–121. in JSTOR

- ^ Lynn M. Case, and Warren E. Spencer, The United States and France: Civil War Diplomacy (1970)

- ^ Kinley J. Brauer, "British Mediation and the American Civil War: A Reconsideration," Journal of Southern History, (1972) 38#1 pp. 49–64 in JSTOR

- ^ Hubbard, Charles M. (1998). The Burden of Confederate Diplomacy. The University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 9781572330924.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Trefousse, pp. 197, 207–208.

- ^ The main scholarly history remains Allan Nevins, Hamilton Fish: The inner history of the Grant administration (two volumes 1937) 932 PP, winner of the Pulitzer Prize. the most recent scholarly survey is Charles W Calhoun, The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant (2017), pages 151-261, 329-61 426-32. The recent one volume biographies summarize the main topics.

- ^ Trefousse 2002, p. 87-88.

- ^ Peskin 1978, pp. 519–521.

- ^ a b Crapol 2000, pp. 62–64.

- ^ Doenecke 1981, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Karabell, pp. 68–71.

- ^ a b Howe, pp. 160–161; Reeves 1975, pp. 255–257.

- ^ Graff, 68-71

- ^ Nevins, 205; 404–405

- ^ Welch, 160

- ^ a b Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 88.

- ^ a b Allan Spetter, "Harrison and Blaine: Foreign Policy, 1889 1893." Indiana Magazine of History (1969) 65#3:214-27. online

- ^ a b A.T. Volwiler, "Harrison, Blaine, and American Foreign Policy, 1889-1893" Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 79#4 1938) pp. 637-648 online

- ^ a b Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 111.

- ^ Milton Plesur, "America Looking Outward: The Years From Hayes to Harrison." The Historian 22.3 (1960): 280-295. Online

- ^ William Michael Morgan, "The anti-Japanese origins of the Hawaiian Annexation treaty of 1897." Diplomatic History 6.1 (1982): 23-44.Online

- ^ Michael J. Devine, "John W. Foster and the Struggle for the Annexation of Hawaii." Pacific Historical Review 46.1 (1977): 29-50 online.

- ^ Graff, 113-114

- ^ Herring, pp. 226-227

- ^ Herring, pp. 228-229

- ^ Herring, pp. 224-229

- ^ Herring, pp. 240-241

- ^ Don H. Doyle, The Cause of All Nations: An International History of the American Civil War (2014) pp 8 (quote), 69-70

- ^ Herring, pp. 235-236

- ^ Herring, pp. 242-246

- ^ a b Howard Jones, Abraham Lincoln and a New Birth of Freedom: the Union and Slavery in the Diplomacy of the Civil War, (1999)

- ^ a b Gallien, Max; Weigand, Florian (December 21, 2021). The Routledge Handbook of Smuggling. Taylor & Francis. p. 321. ISBN 9-7810-0050-8772.

- ^ Kinley J. Brauer, "British Mediation and the American Civil War: A Reconsideration," Journal of Southern History, (1972) 38#1 pp. 49–64 in JSTOR

- ^ Stahr (2012) pp. 307-323.

- ^ a b David Keys (24 June 2014). "Historians reveal secrets of UK gun-running which lengthened the American civil war by two years". The Independent.

- ^ Frank J. Merli, The Alabama, British Neutrality, and the American Civil War. (2004)

- ^ Herring, pp. 225, 243-244

- ^ Herring, pp. 252-253

- ^ Castel, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Michele Cunningham, Mexico and the foreign policy of Napoleon III. (2001); see PhD version of the book online.

- ^ Barnard.

- ^ Hoogenboom, pp. 335–338.

- ^ Rachel St. John, Line in the sand: A history of the Western US-Mexico border (Princeton UP, 2012).

- ^ The main scholarly history remains Allan Nevins, Hamilton Fish: The inner history of the Grant administration (two volumes 1937, 932 pages), winner of the Pulitzer Prize. The most recent scholarly survey is Charles W Calhoun, The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant (2017), pp. 151–261, 329–361 426–432. The recent one-volume biographies summarize the main topics.

- ^ Robert C. Smith, "Presidential Responsiveness to Black Interests From Grant to Biden: The Power of the Vote, the Power of Protest." Presidential Studies Quarterly 52.3 (2022): 648-670 .

- ^ McFeely 2002, p. 337.

- ^ Brands 2012a, pp. 445–456

- ^ American Heritage (December 1981), The Ten Best Secretaries Of States, volume 33, issue 1,

- ^ a b c d American Heritage Editors (December, 1981), The Ten Best Secretaries Of State....

- ^ Fuller 1931, p. 398.

- ^ United States Department of State (December 4, 1871), Foreign relations of the United States, pp. 775–777.

- ^ Kremer 1991, pp. 82–87

- ^ Corning 1918, p. 58.

- ^ a b Smith 2001, pp. 499–502.

- ^ a b c d e Grant 1990, pp. 1145–1147.

- ^ a b Harold T. Pinkett, "Efforts to Annex Santo Domingo to the United States, 1866–1871." Journal of Negro History 26.1 (1941): 12–45. in JSTOR

- ^ a b David Donald, Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man (1970) p 442—43

- ^ a b Simon (1995), The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, p. xxi

- ^ a b McFeely 2002, p. 344.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Smith 2001, p. 505.

- ^ a b c d McFeely 2002, p. 277.

- ^ Chamberlain 1902, pp. 7, 8.

- ^ a b David Donald, Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man (1970) p 446—47

- ^ a b Smith 2001, pp. 503–505.

- ^ Nevins 1957, ch. 12.

- ^ McFeely 2002, pp. 343–345.

- ^ McFeely 2002, pp. 337–345.

- ^ Charles Campbell, The Transformation of American Foreign Relations (1976) pp. 53–59.

- ^ Corning 1918, pp. 49–54.

- ^ Hackett 1911, pp. 45–50.

- ^ "Alabama Claims, 1862-1872". GlobalSecurity.org.

- ^ a b c d Corning 1918, pp. 59–84

- ^ a b Grant 1990, p. 1146.

- ^ a b c d Grant 1990, p. 1148.

- ^ Nevins 1957, ch. 22–23.

- ^ a b c d Miller 1997, pp. 146–147

- ^ Chang 2003.

- ^ Halvdan Koht, "The Origin of Seward's Plan to Purchase the Danish West Indies." American Historical Review 50.4 (1945): 762-767. Online

- ^ David E. Shi, "Seward's Attempt to Annex British Columbia, 1865-1869." Pacific Historical Review 47.2 (1978): 217-238. online

- ^ David M. Pletcher (1998). The Diplomacy of Trade and Investment: American Economic Expansion in the Hemisphere, 1865–1900. University of Missouri Press. p. 160. ISBN 9780826211279.

- ^ Castel, p. 120.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Castel, pp. 120–122.

- ^ Richard E. Welch, "American public opinion and the purchase of Russian America." American Slavic and East European Review 17#4 (1958): 481-494 online

- ^ a b c Grant 1990, pp. 1145–47.

- ^ Chamberlain 1902, pp. 7, 8

- ^ McFeely 2002, pp. 343–45.

- ^ McFeely 2002, pp. 337–45.

- ^ Hereward Senior (1991). The Last Invasion of Canada: The Fenian Raids, 1866-1870. Dundurn. pp. 70–98. ISBN 9781550020854.

- ^ Charles Perry Stacey, "Fenianism and the Rise of National Feeling in Canada at the Time of Confederation." Canadian Historical Review 12.3 (1931): 238-261.

- ^ Hackett 1911, pp. 45–50.

- ^ Moore & Hale, pp. 135–136; Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 137–143.

- ^ John J. Bukowczyk et al. Permeable Border: The Great Lakes Region as Transnational Region, 1650–1990 (University of Pittsburgh Press. 2005)

- ^ J. Castell Hopkins, The Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs: 1902 (1903), p. 327.

- ^ Charles Campbell, The Transformation of American Foreign Relations (1976) pp 53=59.

- ^ Corning 1918, pp. 49–54.

- ^ Bradford 1980.

- ^ Welch, 194–198

- ^ a b Hoogenboom, p. 387.

- ^ a b Bodenner, Christ (February 6, 2013) [October 20, 2006]. "Chinese Exclusion Act" (PDF). Issues & Controversies in American History. Infobase Publishing. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-06. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- ^ a b Hoogenboom, pp. 388–389; Barnard, pp. 447–449.

- ^ a b c Hoogenboom, pp. 390–391.

- ^ Karabell, pp. 82–84.

- ^ a b Reeves 1975, pp. 278–279; Doenecke 1981, pp. 81–84.

- ^ Welch, 72–73

- ^ a b Hoogenboom, p. 416.

- ^ a b Crapol 2000, pp. 65–66; Doenecke 1981, pp. 55–57.

- ^ Crapol 2000, p. 70; Doenecke 1981, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Graff, 123–125; Nevins, 633–642

- ^ Welch, 183–184

- ^ Welch, 186–187

- ^ Graff, 123–25

- ^ Welch, 192–194

- ^ a b Doenecke 1981, pp. 173–175; Reeves 1975, pp. 398–399, 409.

- ^ Doenecke 1981, pp. 175–178; Reeves 1975, pp. 398–399, 407–410.

- ^ Feldman, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, pp. 74–76.

- ^ Moore & Hale, p. 108.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 117–120.

- ^ Allan B. Spetter, "Harrison and Blaine: No Reciprocity for Canada." Canadian Review of American Studies 12.2 (1981): 143-156.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 126–128.

- ^ For the largest dispute see John L. Gignilliat, "Pigs, politics, and protection: the European boycott of American pork, 1879-1891." Agricultural History 35.1 (1961): 3-12 online.

- ^ Reeves 1975, p. 337; Doenecke 1981, p. 145.

- ^ Doenecke 1981, pp. 147–149.

- ^ a b Reeves 1975, pp. 342–343; Abbot, pp. 346–347.

- ^ Karabell, pp. 117–118.

- ^ a b c Reeves 1975, pp. 343–345; Doenecke 1981, pp. 149–151.

- ^ Reeves 1975, pp. 349–350; Doenecke 1981, pp. 152–153.

- ^ ??? K. J. Bauer and Stephen Roberts, Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775-1990: Major Combatant (1991).

- ^ Bauer and Roberts, pp. 101-2, 133, 141–147

- ^ Bruce N. Canfield "The Foreign Rifle: U.S. Krag–Jørgensen" American Rifleman October 2010 pp.86–89,126&129

- ^ Hanevik, Karl Egil (1998). Norske Militærgeværer etter 1867

- ^ Friedman, pp. 35–38

- ^ Bauer and Roberts, pp. 162–165

- ^ Bauer and Roberts, pp. 102–104, 162–165

- ^ Graff, 95-96

- ^ Welch, 166–169

- ^ Spencer Tucker, ed. (2009). The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 569–70. ISBN 9781851099511.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 114–116.