Frauenkirche, Dresden

| Frauenkirche | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Evangelical-Lutheran Church of Saxony |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Parish church |

| Location | |

| Location | Dresden, Germany |

| Geographic coordinates | 51°3′7″N 13°44′30″E / 51.05194°N 13.74167°E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | George Bähr |

| Style | Baroque |

| Groundbreaking | 1726/1993 |

| Completed | 1743/2005 |

| Website | |

| Official Website | |

The Frauenkirche (IPA: [ˈfʁaʊənˌkɪʁçə], Church of Our Lady) is a Lutheran church in Dresden, the capital of the German state of Saxony. Destroyed during the Allied firebombing of Dresden towards the end of World War II, the church was reconstructed between 1994 and 2005.

The current structure is the third church building to stand at this site. The earliest was founded as a Catholic church before being converted to Protestantism during the Reformation. It was replaced in the 18th century by a larger Baroque purpose-built Lutheran building. When its foundation stone was laid on 26 August 1726, it contained a copy of the Augsburg Confession which is primary confession of faith of the Evangelical Lutheran Church. [1] Considered an outstanding example of Protestant sacred architecture, it featured one of the largest domes in Europe. It was originally built as a sign of the will of the citizens of Dresden to remain Protestant after their ruler had converted to Catholicism. Having been reconstructed, it now also serves as a symbol of reconciliation between former warring enemies.

After the destruction of the church in 1945, the remaining ruins were left for nearly half a century as a war memorial, following decisions of local East German leaders. Following the reunification of Germany, it was decided to rebuild the church, starting in 1994. The reconstruction of its exterior was completed in 2004, and the interior the following year. The church was reconsecrated on 30 October 2005 with festive services lasting through the Protestant observance of Reformation Day on 31 October. The surrounding Neumarkt square with its many valuable baroque buildings was also reconstructed in 2004.

The Frauenkirche is often called a cathedral, but it is not the seat of a bishop; the church of the Landesbischof of the Evangelical-Lutheran Church of Saxony is the Church of the Cross. Once a month, an Anglican Evensong is held in English, by clergy from St. George's Anglican Church, Berlin.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2013) |

A church dedicated to 'Our Lady' (Kirche zu unser Liebfrauen) was first built in the 11th century in a Romanesque style, outside the city walls and surrounded by a graveyard. The Frauenkirche was the seat of an archpriest in the Meissen Diocese until the Reformation, when it became a Protestant church. This first Frauenkirche was torn down in 1727 and replaced by a new, larger church with a greater capacity. The Frauenkirche was re-built as a Lutheran (Protestant) parish church by the citizenry. Even though Saxony's Prince-elector, Frederick August I, had converted to Catholicism to become King of Poland, he supported the construction which not only gave an impressive cupola to the Dresden townscape but also reassured the Saxonians that their ruler was not going to force the principle cuius regio, eius religio upon them.

The original Baroque church was built between 1726 and 1743, and was designed by Dresden's city architect, George Bähr, who did not live to see the completion of his greatest work.[2][3] Bähr's distinctive design for the church captured the new spirit of the Protestant liturgy by placing the altar, pulpit, and baptismal font directly centre in view of the entire congregation.

In 1736, famed organ maker Gottfried Silbermann built a three-manual, 43-stop instrument for the church. The organ was dedicated on 25 November and Johann Sebastian Bach gave a recital on the instrument on 1 December.

The church's most distinctive feature was its unconventional high dome, 67 metres (220 ft) high, called die Steinerne Glocke or "Stone Bell". An engineering feat comparable to Michelangelo's dome for St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, the Frauenkirche's 12,000-ton sandstone dome stood high resting on eight slender supports. Despite initial doubts, the dome proved to be extremely stable. Witnesses in 1760 said that the dome had been hit by more than 100 cannonballs fired by the Prussian army led by Friedrich II during the Seven Years' War. The projectiles bounced off and the church survived.

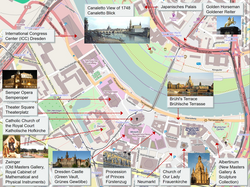

The completed church gave the city of Dresden a distinctive silhouette, captured in famous paintings by Bernardo Bellotto, a nephew of the artist Canaletto (also known by the same name), and in Dresden by Moonlight (1839) by Norwegian painter Johan Christian Dahl.

In 1849, the church was at the heart of the revolutionary disturbances known as the May Uprising. It was surrounded by barricades, and fighting lasted for days before those rebels who had not already fled were rounded up in the church and arrested.

For more than 200 years, the bell-shaped dome stood over the skyline of old Dresden, dominating the city.

Burials include Heinrich Schütz and George Bähr.

Destruction

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

On 13 February 1945, Allied forces began the bombing of Dresden in World War II. The church withstood two days and nights of the attacks, and the eight interior sandstone pillars supporting the large dome held up long enough for the evacuation of 300 people who had sought shelter in the church crypt, before succumbing to the heat generated by some 650,000 incendiary bombs that were dropped on the city. The temperature surrounding and inside the church eventually reached 1,000 °C (1,830 °F).[4] The dome finally collapsed at 10 a.m. on 15 February. The pillars glowed bright red and exploded; the outer walls shattered and nearly 6,000 tons of stone plunged to earth, penetrating the massive floor as it fell.

The altar, a relief depiction of Jesus' Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane on the Mount of Olives by Johann Christian Feige, was only partially damaged during the bombing raid and fire that destroyed the church. The altar and the structure behind it, the chancel, were among the remnants left standing. Features of most of the figures were lopped off by falling debris and the fragments lay under the rubble.

The building vanished from Dresden's skyline, and the blackened stones would lie in wait in a pile in the centre of the city for the next 45 years as Communist rule enveloped what was now East Germany. Shortly after the end of World War II, residents of Dresden had already begun salvaging unique stone fragments from the Church of Our Lady and numbering them for future use in reconstruction. Popular sentiment discouraged the authorities from clearing the ruins away to make a car park. In 1966, the remnants were officially declared a "memorial against war", and state-controlled commemorations were held there on the anniversaries of the destruction of Dresden.

In 1982, the ruins began to be the site of a peace movement combined with peaceful protests against the East German regime. On the anniversary of the bombing, 400 citizens of Dresden came to the ruins in silence with flowers and candles, part of a growing East German civil rights movement. By 1989, the number of protesters in Dresden, Leipzig, and other parts of East Germany had increased to tens of thousands. On 9 November 1989, the Berlin Wall "fell" and the inner German border dividing East and West Germany toppled. This opened the way to German reunification.

Promoting reconstruction and funding

[edit]

During the last months of World War II, residents expressed the desire to rebuild the church. However, due to political circumstances in East Germany, the reconstruction came to a halt. The heap of ruins was conserved as a war memorial within the inner city of Dresden, as a direct counterpart to the ruins of Coventry Cathedral, which was destroyed by German bombing in 1940 and also serves as a war memorial in the United Kingdom. Because of the continuing decay of the ruins, Dresden leaders decided in 1985 (after the Semperoper was finally finished) to rebuild the Church of Our Lady after the completion of the reconstruction of Dresden Castle.

The reunification of Germany, brought new life to the reconstruction plans. In 1989, a 14-member group of enthusiasts headed by Ludwig Güttler, a noted Dresden musician, formed a Citizens' Initiative. From that group emerged a year later The Society to Promote the Reconstruction of the Church of Our Lady, which began an aggressive private fund-raising campaign. The organisation grew to over 5,000 members in Germany and 20 other countries. A string of German auxiliary groups were formed, and three promotional organisations were created abroad.

The project gathered momentum. As hundreds of architects, art historians and engineers sorted the thousands of stones, identifying and labeling each for reuse in the new structure, others worked to raise money. IBM provided a key element by contracting with RTI International, a nonprofit research institute in Research Triangle Park NC to create an interactive virtual reality representation of the Church. The VR drew donations large and small, helping to make the project possible.

Günter Blobel, a German-born American, saw the original Church of Our Lady as a boy when his refugee family took shelter in a town just outside Dresden days before the city was bombed. In 1994, he became the founder and president of the nonprofit "Friends of Dresden, Inc.", a United States organization dedicated to supporting the reconstruction, restoration, and preservation of Dresden's artistic and architectural legacy. In 1999, Blobel won the Nobel Prize for medicine and donated the entire amount of his award money (nearly US$1 million) to the organization for the restoration of Dresden, to the rebuilding of the Frauenkirche and the building of a new synagogue. It was the single largest individual donation to the project.

In Britain, the Dresden Trust has Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, as its royal patron and the Bishop of Coventry among its curators. Dr. Paul Oestreicher, a canon emeritus of Coventry Cathedral and a founder of the Dresden Trust, wrote: "The church is to Dresden what St. Paul's is to London".[5] (Referring to St. Paul's Cathedral.) Additional organizations include France's Association Frauenkirche Paris and Switzerland's Verein Schweizer Freunde der Frauenkirch.

Rebuilding the church cost €180 million. Dresdner Bank financed more than half of the reconstruction costs via a "donor certificates campaign", collecting almost €70 million after 1995. The bank itself contributed more than seven million Euros, including more than one million donated by its employees. Over the years, thousands of watches containing tiny fragments of Church of Our Lady stone were sold, as were specially printed medals. One sponsor raised nearly €2.3 million through symbolic sales of individual church stones.

Funds raised were turned over to the "Frauenkirche Foundation Dresden", with the reconstruction backed by the State of Saxony, the City of Dresden and the Evangelical-Lutheran Church of Saxony.

The new golden tower cross was funded officially by "the British people and the House of Windsor". It was made by the British silversmith company Grant Macdonald of which the main craftsman on the project was Alan Smith whose father was one of the bomber pilots responsible for the destruction of the church.[6][7][8]

Reconstruction

[edit]

Using original plans from builder Georg Bähr in the 1720s, the Dresden City Council decided to proceed with reconstruction in February 1992. A rubble-sorting ceremony started the event in January 1993 under the direction of church architect and engineer Eberhard Burger. The foundation stone was laid in 1994, and stabilized in 1995.[9] The crypt was completed in 1996[9] and the inner cupola in 2000. Seven new bells were cast for the church and rang for the first time for the Pentecost celebration in 2003. The exterior was completed ahead of schedule in 2004 and the interior painted in 2005.[9] The intensive efforts to rebuild this world-famous landmark were completed in 2005, one year earlier than originally planned, and in time for the 800-year anniversary of the city of Dresden in 2006.[9]

The church was reconsecrated with a festive service one day before Reformation Day. The rebuilt church is a monument reminding people of its history and a symbol of hope and reconciliation.

As far as possible, the church – except for its dome – was rebuilt using original material and plans, with the help of modern technology. The heap of rubble was documented and carried off stone by stone. The approximate original position of each stone could be determined from its position in the heap. Every usable piece was measured and catalogued. A computer imaging program that could move the stones three-dimensionally around the screen in various configurations was used to help architects find where the original stones sat and how they fit together.[10]

Of the millions of stones used in the rebuilding, more than 8,500 original stones were salvaged from the original church and approximately 3,800 reused in the reconstruction. As the older stones are covered with a darker patina, due to fire damage and weathering, the difference between old and new stones will be clearly visible for many years after reconstruction.

Two thousand pieces of the original altar were cleaned and incorporated into the new structure.

The builders relied on thousands of old photographs, memories of worshippers and church officials, and crumbling old purchase orders detailing the quality of the mortar or pigments of the paint (as in the 18th century, copious quantities of eggs were used to make the color that provides the interior with its almost luminescent glow).

When it came time to duplicate the oak doors of the entrance, the builders had only vague descriptions of the detailed carving. Because people (especially wedding parties) often posed for photos outside the church doors, they issued an appeal for old photographs and the response – which included entire wedding albums – allowed artisans to recreate the original doors.

The new gilded orb and cross on top of the dome was forged by Grant Macdonald Silversmiths in London using the original 18th-century techniques as much as possible. It was constructed by Alan Smith, a British goldsmith from London whose father, Frank, was a member of one of the aircrews who took part in the bombing of Dresden.[11] Before travelling to Dresden, the cross was exhibited for five years in churches across the United Kingdom including Coventry Cathedral, Liverpool Cathedral, St Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh, and St Paul's Cathedral in London. In February 2000, the cross was ceremonially handed over by Prince Edward, Duke of Kent,[4] to be placed on the top of the dome a few days after the 60th commemoration of D-Day on 22 June 2004.[12] The external structure of the Frauenkirche was completed. For the first time since the last war, the completed dome and its gilded cross grace Dresden's skyline as in centuries prior. The cross that once topped the dome, now twisted and charred, stands to the right of the new altar.

Builders decided not to reproduce the 1736 Gottfried Silbermann organ, despite the fact that the original design papers, description, and details exist, giving rise to the Dresden organ dispute ("Dresdner Orgelstreit").[13] When installed, the Silbermann organ had three manuals with 43 ranks and over the years had been remodeled and expanded to five manuals with 80 ranks.[14] Daniel Kern of Strasbourg, Alsace, completed a 4,873 pipe organ for the structure in April 2005 and it was inaugurated in October of that year; Samuel Kummer was the organist until 2022. The Kern organ contains all the stops which were in the Silbermann organ and attempts to recreate their sounds. The Kern work contains 68 stops and a fourth swell manual in the symphonic 19th century style which is apt for the organ literature composed after the baroque period.

A bronze statue of reformer and theologian Martin Luther, which survived the bombings, has been restored and again stands in front of the church. It is the work of sculptor Adolf von Donndorf from 1885.

There are two devotional services every day and two liturgies every Sunday. Since October 2005, there has been an exhibition on the history and reconstruction of the Frauenkirche at the Stadtmuseum (City Museum) in Dresden's Alten Landhaus.

Since the re-opening

[edit]Since re-opening, the Church of Our Lady has been a tourist destination in Dresden. In the first three years, seven million people have visited the church as tourists and to attend worship services.[15] The project has inspired other revitalization projects throughout Europe, including the Dom-Römer Project in Frankfurt, the City Palace of Potsdam, and the City Palace, Berlin. In 2009, US President Barack Obama visited the church after a meeting with German Chancellor Angela Merkel in the Grünes Gewölbe.[citation needed]

Criticisms of reconstruction methods

[edit]Architectural historian Mark Jarzombek complained that unidentifiable parts of the ruins were placed in arbitrary locations in the new building. As a result, he said, the socialist monument to the bombing was, in essence, dispersed throughout the fabric of the building.[16]

See also

[edit]- Stiftung Frauenkirche Dresden

- Frauenkirchhof (Dresden)

- The Reformation and its influence on church architecture

- List of tallest domes

- Cathedral of Christ the Saviour (Moscow)

- Royal Castle, Warsaw

- History of early modern period domes

References

[edit]- ^ Heal, Bridget (2017), A Magnificent Faith: Art and Identity in Lutheran Germany, Oxford University Press, 2017, ISBN 0191057541, 9780191057540, google books

- ^ Sturgis, Russell (1901). A Dictionary of Architecture and Building, Volume I. Macmillan. p. 185.

- ^ Fleming, John; Honour, Hugh; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1998). The Penguin Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (5 ed.). Penguin. p. 23. ISBN 0-14-051323-X.

- ^ a b "Duke leads Dresden tribute". BBC News. bbc.com. 13 February 2000. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ Harding, Luke (20 October 2005). "Cathedral hit by RAF is rebuilt". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Orb and Cross". The Dresden Trust. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ "Out of Dresden's ruins, hope". The Independent. 29 November 1998. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ "Tower Cross". Frauenkirche Dresden. Archived from the original on 16 September 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c d Lambourne, Nicola (2006). "Reconstruction of the City's Monuments". In Addison, Paul; Crang, Jeremy A. (eds.). Firestorm: The Bombing of Dresden, 1945. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-56663-713-8.

- ^ In Dresden, Freedom Rises From The Rubble, Civilization, May–June 1995, pp 2–3

- ^ "Dresden Cross presented at Windsor". BBC News. bbc.com. 1 December 1998. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Dresden ruins finally restored". BBC News. bbc.com. 22 June 2004. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Dresdner Frauenkirchen-Orgelstreit eskaliert – neue musikzeitung". nmz (in German). 22 February 2002. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ "The Original Pipe Organ of Gottfried Silbermann". Daniel Kern Manufacture d'Orgues. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "Frauenkirche Dresden one of the top tourist attractions" (Press release). Dresden Tourist Promotion Board. 24 January 2008. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

{{cite press release}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ By Eleni Bastea, ed. (30 December 2004). "Two: Disguised Visibilities – Dresden/"Dresden". Memory and Architecture (PDF). University of Mexico Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-8263-3269-1. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

External links

[edit]- Frauenkirche Dresden Official German website. Includes historical and current pictures.

- The Frauenkirche – a page from the Library of Congress website, from which part of this article was copied

- Live Webcam showing the Frauenkirche

- Hourly webcam pictures from the Neumarkt square, with the construction history in pictures

- Gunther Blobel's autobiography

- Homepage of the "Gesellschaft Historischer Neumarkt Dresden e.V." (Society for the rebuilding of the Historical Neumarkt Dresden)

- Frauenkirche organ (article in Pipe Organ Taxonomy project)

- Video (2023) about the Reconstruction of Dresden and its Frauenkirche, Neumarkt and surrounding areas by "The Aesthetic City" channel on YouTube

- Baroque architecture in Dresden

- Buildings and structures in Germany destroyed during World War II

- Church buildings with domes

- Destroyed churches in Germany

- Lutheran art

- Lutheran churches in Dresden

- Rebuilt buildings and structures in Dresden

- 18th-century Lutheran churches in Germany

- Churches completed in 1743

- Churches completed in 2005

- Rebuilt churches in Germany

- Tourist attractions in Dresden