Enigmosaurus

| Enigmosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

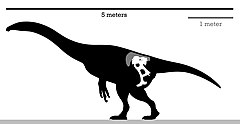

| Skeletal diagram of the holotype | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | †Therizinosauria |

| Superfamily: | †Therizinosauroidea |

| Genus: | †Enigmosaurus Barsbold, 1983 |

| Type species | |

| †Enigmosaurus mongoliensis Barsbold, 1983

| |

Enigmosaurus (meaning "Enigma lizard" or "Enigmatic lizard") is a genus of therizinosauroid that lived in Asia during the Late Cretaceous period. It was a medium-sized, ground-dwelling, bipedal herbivore that represents the third therizinosaur taxon from the Bayan Shireh Formation, although it is known from the lower part. The genus is monotypic, including only the type species E. mongoliensis, known from a well preserved pelvis and other tentative body remains.

Discovery and naming

[edit]

The holotype, IGM 100/84, was discovered at the Khara Khutul locality in the Bayan Shireh Formation (sometimes called Baynshire Formation or the Baynshirenskaya Svita), southeastern Mongolia, dating from the Late Cretaceous period, and first reported in 1979 on a pelvic comparison with other theropod dinosaurs. At the time, little was known about therizinosaurs.[1] In 1980, it was mentioned again, this time in the new infraorder created by the Mongolian paleontologists Rinchen Barsbold and Altangerel Perle: Segnosauria. Nicknamed as the "Dinosaur from Khara Khutul", it was shortly described and included into the Segnosauria.[2]

Three years later, the type species, Enigmosaurus mongoliensis, was named and described in 1983 by Barsbold. The preserved elements consist of a partial skeleton, lacking the skull, that includes a well preserved pelvic girdle with other postcrania. The generic name, Enigmosaurus, was stated to be derived from Greek αίνιγμα (aínigma, meaning enigma) and σαῦρος (sauros, meaning lizard), in reference to the aberratic and unusual shape of its pelvis. The specific name, mongoliensis, refers to the country of its discovery, Mongolia.[3] Some therizinosaur fossil findings at the Iren Dabasu Formation were first thought to be referable to Enigmosaurus.[4] Although it is commonly known from the pelvis, several remains not mentioned in the original description of the holotype were labelled under the same specimen number (IGM 100/84). These elements are in poor condition compared to the pelvis, and they were not measured and illustrated: proximal end of a femur; large femoral shaft, might be a tibial shaft; some ribs; distal end of a humerus; a tentative radius and the proximal end of an ulna. The femur however, was not found in association with the holotype individual, therefore it should be assigned to Therizinosauria incertae sedis; the other remains might pertain to the holotype. A very large left femur, measuring 105 cm (1,050 mm) long, was labelled with the same specimen number too, however, it was not associated with the holotype due to its large size (larger than the pelvis itself). Nevertheless, it seems to approach the size of the closer Segnosaurus.[5]

Possible synonymy with Erlikosaurus

[edit]Some paleontologists proposed that Enigmosaurus was likely the same animal as Erlikosaurus, since both were found in the same geologic formation, Enigmosaurus is known from pelvic remains, whereas the pelvis of Erlikosaurus is unknown and distinguishing traits between them were absent; if proven, this would make Enigmosaurus a junior synonym of Erlikosaurus.[6][7] However, the Enigmosaurus pelvis doesn't resemble that of Segnosaurus as would be expected for the connection with Erlikosaurus, and there is a huge size difference.[2][3][8] In addition, both genera are known from different strata (lower and upper),[3][9][10] and they are considered to be distinct animals by most authors.[11][12]

Description

[edit]

Enigmosaurus was a relatively large-bodied therizinosaur, with an estimated length of 5 m (16 ft) and a weight between 454 to 907 kg (1,001 to 2,000 lb).[13] As noted by Barsbold in the original description of Enigmosaurus, it can recognised by the following characteristics: the pubis and ischium are short; elongated margin in the anterior presymphyseal region of the distal pubis.[3] However, in the revised diagnosis by Zanno et al. 2010, there are even more specific traits for Enigmosaurus that were not pointed out/analyzed before: prominent cranial and caudal processes on the dorsoventrally somewhat flattened pubic boot; the pubic feet are fused, being medially elongated, a medial expansion forms a V-shaped structure; the medial fusion of the obturator process and pubic body, forms a tetraradiate process.[5]

The holotype pelvis is in relatively good preservation, compromising the sacral vertebrae, partial ilium, right and left pubis and the left ischium. The pelvis is somewhat large as a whole and opisthopubic. The ilium is widely positioned and turned externally; it preserves a large cubic process in the posterodorsal area. Elongated pubic peduncles are present in the ilium; the ischial peduncles are more reduced though. The distal end of the pubis is elongated, recurved and stocky. The ischium, is slightly shorter than the pubis and parallel to it, with a narrow shaft. The obturator process on the front edge of the ischium is horizontally elongated and low. Open edges are appreciable on the large trochanteric fossa. Apparently, the sacrum preserves six vertebrae, with elongated transverse processes.[3] For instance, its pelvis is very particular compared to other therizinosaur relatives, featuring areas of bone resorption and bone remodeling on the ilium. These specific traits may indicate the advanced age of the individual, if true, the fusion of the obturator process and pubic body could be discarded as an authentic autapomorphy for the species. Zanno noted that more analyses are required to settle this enigma.[5]

Classification

[edit]Enigmosaurus was by the describers assigned to a separate Enigmosauridae (now obsolete) due to its aberrant pelvis, but later considered a member of the Segnosauridae which are today called the Therizinosauridae.[3] Lindsay Zanno in 2010 recovered a position more basal in the Therizinosauroidea.[5]

Below are the results of the recently performed phylogenetic analysis of the Therizinosauria by Hartman et al. 2019, in which Enigmosaurus is recovered as a derived therizinosauroid.[12]

| Therizinosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

[edit]

The remains of Enigmosaurus were found in sediments that were deposited during the Late Cretaceous period on the Bayan Shireh Formation, Khara Khutul locality, about 95.9 ± 6.0 million to 89.6 ± 4.0 million years ago, Cenomanian-Santonian ages.[3][14] Being a therizinosaur, it was likely a slow herbivore and/or omnivore, as suggested by most authors all over the time.[15][16][17] The biodiversity across the formation was characterized by therizinosaurs, as seen on the remains of Enigmosaurus, Erlikosaurus and Segnosaurus.[18] The holotype location, Khara Khutul, has also yielded the contemporary Segnosaurus[2] and an unnamed velociraptorine.[19][20] Most of the remaining paleofauna from this formation is known from Upper strata, whereas Enigmosaurus is known from Lower strata.[10]

At the locality, diverse paleoflora has been discovered, such as Cornaceae reported with Bothrocaryum gobience and Nyssoidea mongolica as fine representatives.[21] Numerous fossil fruit findings at the locality reflect the large presence of angiosperm plants on the formation. The unearthed fruits bear some resemblance with Abelmoschus esculentus, however, definitive taxonomic affinities are quite unclear.[22]

See also

[edit]- Timeline of therizinosaur research

- Rinchen Barsbold

- Glossary of dinosaur anatomy

- Anatomical terms of location

References

[edit]- ^ Barsbold, R. (1979). "Opisthopubic pelvis in the carnivorous dinosaurs". Nature. 279 (5716): 792–793. Bibcode:1979Natur.279..792B. doi:10.1038/279792a0. S2CID 4348297.

- ^ a b c Barsbold, R.; Perle, A. (1980). "Segnosauria, a new suborder of carnivorous dinosaurs" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 25 (2): 190–192.

- ^ a b c d e f g Barsbold, R. (1983). "Хищные динозавры мела Монголии" [Carnivorous dinosaurs from the Cretaceous of Mongolia] (PDF). Transactions of the Joint Soviet-Mongolian Paleontological Expedition (in Russian). 19: 89. Translated paper

- ^ Currie, P. J.; Eberth, D. A. (1993). "Palaeontology, sedimentology and palaeoecology of the Iren Dabasu Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Inner Mongolia, People's Republic of China". Cretaceous Research. 14 (2): 138. doi:10.1006/cres.1993.1011.

- ^ a b c d Zanno, L. E. (2010). "A taxonomic and phylogenetic re-evaluation of Therizinosauria (Dinosauria: Maniraptora)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 8 (4): 503–543. doi:10.1080/14772019.2010.488045. S2CID 53405097.

- ^ Clark, J. M.; Maryańska, T.; Barsbold, R. (2004). "Therizinosauroidea". The Dinosauria. University of California Press. p. 159. ISBN 9780520242098.

- ^ Paul, G. S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-6911-3720-9.

- ^ Dodson, P. (1993). "Erlikosaurus". The Age of Dinosaurs. Publications International, LTD. p. 142. ISBN 0-7853-0443-6.

- ^ Clark, J. M.; Perle, A.; Norell, M. (1994). "The skull of Erlicosaurus andrewsi, a Late Cretaceous "Segnosaur" (Theropoda, Therizinosauridae) from Mongolia". American Museum Novitates (3115): 1–39. hdl:2246/3712.

- ^ a b Tsogtbaatar, K.; Weishampel, D. B.; Evans, D. C.; Watabe, M. (2019). "A new hadrosauroid (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the Late Cretaceous Baynshire Formation of the Gobi Desert (Mongolia)". PLOS ONE. 14 (4): e0208480. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1408480T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208480. PMC 6469754. PMID 30995236.

- ^ Stephan, L.; Emily, J. R.; Perle, A.; Lindsay, E. Z.; Lawrence, M. W. (2012). "The Endocranial Anatomy of Therizinosauria and Its Implications for Sensory and Cognitive Function". PLOS ONE. 7 (12): e52289. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...752289L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052289. PMC 3526574. PMID 23284972.

- ^ a b Hartman, S.; Mortimer, M.; Wahl, W. R.; Lomax, D. R.; Lippincott, J.; Lovelace, D. M. (2019). "A new paravian dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of North America supports a late acquisition of avian flight". PeerJ. 7: e7247. doi:10.7717/peerj.7247. PMC 6626525. PMID 31333906.

- ^ Holtz, T. R.; Rey, L. V. (2007). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. Random House. Genus List for Holtz 2012 Weight Information

- ^ Kurumada, Y.; Aoki, S.; Aoki, K.; Kato, D.; Saneyoshi, M.; Tsogtbaatar, K.; Windley, B. F.; Ishigaki, S. (2020). "Calcite U–Pb age of the Cretaceous vertebrate‐bearing Bayn Shire Formation in the Eastern Gobi Desert of Mongolia: usefulness of caliche for age determination". Terra Nova. 32 (4): 246–252. Bibcode:2020TeNov..32..246K. doi:10.1111/ter.12456.

- ^ Paul, G. S. (1984). "The segnosaurian dinosaurs: relics of the prosauropod-ornithischian transition?". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 4 (4): 507–515. doi:10.1080/02724634.1984.10012026. ISSN 0272-4634. JSTOR 4523011.

- ^ Zanno, L. E.; Tsogtbaatar, K.; Chinzorig, T.; Gates, T. A. (2016). "Specializations of the mandibular anatomy and dentition of Segnosaurus galbinensis (Theropoda: Therizinosauria)". PeerJ. 4: e1885. doi:10.7717/peerj.1885. PMC 4824891. PMID 27069815.

- ^ Macaluso, L.; Tschopp, E.; Mannion, P. (2018). "Evolutionary changes in pubic orientation in dinosaurs are more strongly correlated with the ventilation system than with herbivory". Palaeontology. 61 (5): 703–719. doi:10.1111/pala.12362. S2CID 133643430.

- ^ Lee, Y. M.; Lee, H. J.; Kobayashi, Y.; Carabajal, A. P.; Barsbold, R.; Fiorillo, A. R.; Tsogtbaatar, K. (2019). "Unusual locomotion behaviour preserved within a crocodyliform trackway from the Upper Cretaceous Bayanshiree Formation of Mongolia and its palaeobiological implications". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 533 (109353): 2. Bibcode:2019PPP...533j9239L. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.109239. S2CID 197584839.

- ^ Kubota, K.; Barsbold, R. (2007). "New dromaeosaurid (Dinosauria Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous Bayanshiree Formation of Mongolia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (suppl. to 3): 102A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2007.10010458.

- ^ Turner, A. H.; Makovicky, P. J.; Norell, M. A. (2012). "A Review of Dromaeosaurid Systematics and Paravian Phylogeny". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 371 (371): 1–206. doi:10.1206/748.1. hdl:2246/6352. S2CID 83572446.

- ^ Khand, Y.; Badamgarav, D.; Ariunchimeg, Y.; Barsbold, R. (2000). "Cretaceous system in Mongolia and its depositional environments". Cretaceous Environments of Asia. Developments in Palaeontology and Stratigraphy. Vol. 17. pp. 49–79. doi:10.1016/s0920-5446(00)80024-2. ISBN 9780444502766.

- ^ Ksepka, D. T.; Norell, M. A. (2006). "Erketu ellisoni, a long-necked sauropod from Bor Guvé (Dornogov Aimag, Mongolia)" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3508): 1–16. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2006)3508[1:EEALSF]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86032547.