Engineers' Club Building

| Engineers' Club Building | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Alternative names | The Columns, Bryant Park Place |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Neoclassical |

| Location | 32 West 40th Street, Manhattan, New York, US |

| Coordinates | 40°45′10″N 73°59′01″W / 40.7527°N 73.9835°W |

| Opened | 1907 |

| Client | Engineers' Club |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 13 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Whitfield & King |

| Designated | August 30, 2007[1] |

| Reference no. | 07000867[1] |

| Designated entity | Engineering Societies' Building and Engineers' Club |

| Designated | July 13, 2007[2] |

| Reference no. | 06101.009379[2] |

| Designated | March 22, 2011[3] |

| Reference no. | 0954[3] |

| Designated entity | Engineers' Club |

The Engineers' Club Building, also known as Bryant Park Place, is a residential building at 32 West 40th Street in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City, United States. Located on the southern edge of Bryant Park, it was constructed in 1907 along with the adjoining Engineering Societies' Building. It served as the clubhouse of the Engineers' Club, a social organization formed in 1888. The building was designed by Henry D. Whitfield and Beverly S. King, of the firm Whitfield & King, in the neo-Renaissance style.

The building's facade is divided into three horizontal sections. The lowest three stories comprise a base of light-colored stone, including a colonnade with Corinthian-style capitals. Above that is a seven-story shaft with a brick facade and stone quoins. The top of the building has a double-height loggia and a cornice with modillions. Inside, the building contained accommodations for the Engineers’ Club, including 66 bedrooms and club meeting rooms. In the early 20th century, the Engineers' Club Building was connected to the Engineering Societies' Building.

The Engineers' Club Building was partially funded by Andrew Carnegie, who in 1904 offered money for a new clubhouse for New York City's various engineering societies. The Engineers' Club did not want to share a building with the other societies, so an architectural design competition was held for two clubhouse buildings. The Engineers' Club Building served as a clubhouse until 1979, after which it became a residential structure. The building became a cooperative apartment called Bryant Park Place in 1983. The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2007, and the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the building as a landmark in 2011.

Site[edit]

The Engineers' Club Building is at 32 West 40th Street in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City.[4][5] The building occupies a rectangular land lot with a frontage of 50 ft (15 m) along 40th Street, a depth of 98.75 ft (30.10 m), and an area of 4,943 sq ft (459.2 m2).[4][6] Two adjacent buildings were once affiliated with the Engineers' Club Building: 28 West 40th Street to the east and 36 West 40th Street to the west.[7] The building was also once connected to the Engineering Societies' Building to the south.[8]

The Engineers' Club Building faces the southern border of Bryant Park between Fifth and Sixth Avenues.[9] On the same block are The Bryant and 452 Fifth Avenue to the east; the Haskins & Sells Building to the south; and the American Radiator Building and Bryant Park Studios to the west. Other nearby places include the New York Public Library Main Branch across 40th Street to the north, as well as the Lord & Taylor Building to the southeast.[4][5]

The surrounding block of 40th Street had contained brownstone row houses through the 1920s.[10][11] The Engineers' Club Building had directly replaced two brownstone row houses at 32 and 34 West 40th Street. Each of these houses was five stories tall with an English basement and was situated on a lot measuring 50 by 99 ft (15 by 30 m).[12][13] The city block already had several social clubs, including the Republican Club and the New York Club, both later demolished.[14][15][16] The Engineering Societies and Engineers' Club buildings collectively served as a center for the engineering industry in the United States during the early and mid-20th century.[17][18] The adjoining area included the offices of three engineering publications on 39th Street,[19] as well as Engineers' Club member Nikola Tesla's laboratory on 8 West 40th Street.[19][20]

Architecture[edit]

The Engineers' Club Building was designed by Henry D. Whitfield and Beverly S. King, of the firm Whitfield & King, in the neo-Renaissance style.[21][22][5] It is 13 stories tall,[23][24] also cited as 12 stories.[25] There is also a basement and subbasement under the above-ground stories.[6][26][27] The building occupies its whole land lot at the base. Above the third story, the building is shaped like a dumbbell, with light courts to the west and east.[19]

Facade[edit]

The primary facade is on the north, facing 40th Street. It is three bays wide and is organized into three horizontal sections: a base, shaft, and capital.[25][28] It uses a combination of white marble and red brick..[29][30] The New York Times wrote the building design "strikes even the layman as sumptuous in the extreme. It is doubtful if anywhere in this country so luxurious a club dwelling exists."[6][31]

The lowest three stories on 40th Street are clad in stone[28][24] and are each 19 ft (5.8 m) tall.[6] The ground story is designed with rusticated blocks and contains a central entrance flanked by round-arched windows. Above the entrance are large console brackets carrying an entablature.[28] The entrance was designed as a doorway 15 ft (4.6 m) wide, while the windows to either side are 6.5 ft (2.0 m) wide and twice as high.[6] There is a plaque commemorating Nikola Tesla, who received an IEEE Edison Medal at the building in 1917.[32][33] There is a Corinthian-style colonnade of fluted pilasters on the second and third stories, with capitals at the top of each pilaster.[23][24][28] According to the AIA Guide to New York City, the pilasters "give this a scale appropriate to the New York Public Library opposite".[5][34] The second-floor windows have eared surrounds, above which are entablatures with swags. The third story has round-arched windows with carved frames. Above is a decorative frieze, as well as a cornice with dentils.[28]

On 40th Street, the fourth through tenth stories are clad in brick, and the outer edges of the facade have stone quoins. The windows are square and have marble frames for the most part.[24][28][35] The fourth story is a transitional story and consists of a stone entablature.[30] Four urns flank the fourth-story windows. On the fourth through ninth stories, there is a console bracket above each window, serving as a keystone. At the tenth story, the windows are flanked by carved shields.[28] A stone balustrade runs above the tenth story and is carried on brackets.[30][28][35]

The top stories contain a double-height colonnade supported by Ionic-style stone columns.[24][28] The arches have a slightly different window arrangement at the base, and there is a brick wall behind each column. Atop each arch is a console bracket supporting an attic.[28] The facade is topped by a cornice with dentils, supporting a stone balcony.[28][35] The west and east elevations are visible above the fifth story and are mostly clad in plain brick with some windows. There are air shafts on both elevations and a fire escape on the western elevation. The Engineers' Club Building was also attached to the immediately adjacent buildings on either side. To the east, the Engineers' Club Building adjoins a brick-and-brownstone structure at 28 West 40th Street, containing four stories and an attic. To the west is a brick structure over a stone storefront at 36 West 40th Street.[7]

Features[edit]

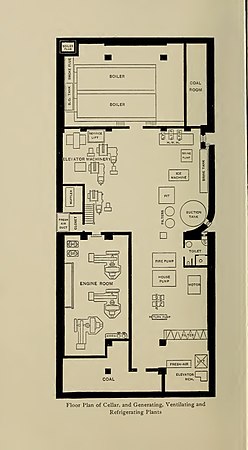

The building is served by a set of service stairs and three elevators. The three elevators and the stairs run from basement to roof; one elevator is designed for freight and the two others are for passengers.[6][36][37] The passenger elevators fit 12 to 15 people and originally skipped the third floor, while the freight elevator serves the whole building.[6] Also in the clubhouse was a dumbwaiter, connecting the lobby, clubroom, and billiards floor.[38][36][39] In addition to the thirteen above-ground levels are two basement levels. The first basement had a restroom and some storage and staff rooms, while the sub-basement had the building's mechanical plant with heat, light, power, and refrigeration.[26][27]

Lower stories[edit]

The main entrance leads to a vestibule, which in turn is connected to the lobby.[7][35] The lobby's piers and Ionic columns made of wood; the wall and the column capitals are made of marble; and the molded ceiling is made with plaster.[7] On the left was the reception room for visitors, while on the right was the writing room for members, containing such furniture as writing tables and mailboxes.[35][40] The reception room was 20 ft (6.1 m) high with predominantly marble decorations.[6] It adjoined a coat room that could store at least 500 items of clothing, and the writing room adjoined an administration office. The ground floor also had a bar, cigar stand, four telephone booths, and a small bathroom.[19][35][40] At the end of the hall was a café with a grill,[35][40] as well as a connection to the Engineering Societies' Building.[19] Both sides of the lobby have been converted into stores.[41] The old grill in the rear of the lobby was converted into an apartment with 14-foot (4.3 m) ceilings.[34]

A grand staircase leads from the west side of the lobby near the center of the house.[6][7][37] The staircase has carved newels as well as a banister with metal decorations. It splits into two legs above the lobby, serving the second- and third-story landings.[6][7] An oil painting of the businessman Andrew Carnegie, who financed part of the building's construction, was hung on the stairway.[39] The third-story landing has a plaster ceiling, a colored-glass oval skylight, and wooden walls.[6][42] The skylight illuminates the lobby floor 60 ft (18 m) below.[6]

The second story was devoted to a lounge/clubroom in the front and a club library in the rear.[30][38][36] The lounge did not contain any columns across its entire width.[6] Two large fireplaces were placed in the lounge, one on either side, and the windows on 40th Street provided ample illumination.[30][39] The library had an oil painting of John Fritz,[39] as well as bookcases on all four sides, with capacity for 18,000 volumes.[6] The third story had a billiards room large enough to accommodate six tables. It was surrounded by a platform about 8 in (200 mm) high, with benches for spectators, and contained an ornamental fireplace at each end. In the rear of the third floor were three large rooms, one each for cards, the house committee, and the board of governors.[38][36] While these spaces have been converted into apartments in the late 20th century, they retain many original design details.[43] The second-floor lounge and library were converted into four apartments, one of which had a mezzanine and an original fireplace.[23]

-

Original sub-basement floor plan of Engineers' Club

-

Original basement floor plan of the Engineers' Club

-

First floor plan of the Engineers' Club (1905)

-

Second floor plan of the Engineers' Club (1905)

Upper stories[edit]

The fourth through ninth stories[27][37] contained sixty-six bedrooms.[23][3] These floors were planned so the rooms could be used en suite or separately. Each bedroom either had an attached bathroom or was connected to one. A common toilet, bath, and shower were also provided off the main corridor of each story.[6][27][37] After 1979, the former bedrooms were rearranged into apartments.[43] Unit 4G, a one-bedroom apartment described by the website Curbed New York as a "mini-Versailles",[44] is decorated with hand-painted murals throughout.[45][46]

Above the bedroom stories were the dining-room stories. The tenth story had two large private dining rooms and a spacious reception room in the front. Next to the elevators was a breakfast room, which could also be used for large private dinners.[27][36][47] This was connected by a covered bridge to the ninth floor of the Engineering Societies' Building.[19] The tenth story also had its own serving rooms[36][47] and a "tapestry room".[48] The eleventh story had a dining room seating 300 people.[23][27][49] Across the eastern light court was a balcony for service staff.[24][36][49] The banquet room opens onto the balcony overlooking Bryant Park.[24][30][35] The twelfth story was entirely for the service staff. It had a main kitchen in the rear, adjacent to a butcher shop and a refrigerator.[49] These stories also have been converted into apartments but retain much of their old wooden decoration. One apartment has a mezzanine.[43]

About half of the attic/roof story was reserved for an open roof garden, while the rear of that floor had service rooms.[24][39][49] The building's elevators ran directly to the roof garden, and two staircases ran to the attic, one each for workers heading upstairs and downstairs. Part of the roof garden was enclosed in glass.[6] The attic had a kitchen, refrigerator room, servants' bedrooms, and servants' dining rooms.[6][49] During the 1940s and 1950s, the attic contained a masseuse and barbershop.[19] The modern attic contains two duplex penthouse apartments.[50]

History[edit]

In 1888, the Engineers' Club of New York was founded at the clubhouse of the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) on 23rd Street.[51][52] The Engineers' Club moved to its own space on 29th Street the following April; its goal was to "embrace all the States of the Union, as well as Canada and Mexico".[51][53][54] The club was intended as a social club and initially had 350 members,[53] but its constitution allowed up to 1,000.[51][53] The New York Times wrote in 1891 that "no end of prominent men have secured admission" to the club,[53][55] which had grown to 650 members by 1896.[51] As a result of its rapid membership growth, the Engineers' Club moved to the Drayton mansion on Fifth Avenue and 35th Street that year.[14][56][57] Even after that relocation, the club's membership had grown to 769 by the end of 1898, prompting the club's officers to survey members about building a larger clubhouse.[51]

Development[edit]

Site acquisition[edit]

In 1902, the club's board of management unanimously decided to build a new clubhouse and raise funds for such a building.[58] The next year, the board formed the Engineers’ Realty Company and asked all members to buy stock in that company. By then, the club had reached 1,000 members and the membership limit had to be increased.[59] The Engineers' Realty Company bought a pair of dwellings at 32 and 34 West 40th Street from William M. Martin in February 1903.[12][13] The club's management cited the site's proximity to transit options, the Theater District, and Fifth Avenue as reasons for selecting the 40th Street site for its clubhouse.[59] The site would also overlook Bryant Park and the under-construction main library building.[29][30][59] The Engineers' Club would purchase the property from the Engineers' Realty Company subject to a $110,000 mortgage. The realty company would receive 1,150 bonds from the club, each with a par value of $100 and a maturity of 20 years; the realty company would distribute one bond to each stockholder and then dissolve thereafter.[60]

Andrew Carnegie acquired five land lots on 39th Street, measuring 125 by 100 ft (38 by 30 m),[61][62] in May 1903.[63][64] Carnegie had acquired these lots specifically because they were directly behind the Engineers' Club.[59][65] Carnegie offered to donate $1 million (about $27.2 million in 2023) to fund the construction of a clubhouse for several engineering societies on that site.[64][66] The engineering building would house the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), American Institute of Mining Engineers (AIME), and American Institute of Electrical Engineers (AIEE).[59][62][65][a] Originally, the Engineers' Club was to occupy space in the engineering building. However, this was deemed logistically prohibitive, so two buildings connected at their rears were developed.[68][69]

In March 1904, Carnegie increased his gift to $1.5 million (about $39.8 million in 2023).[70][71] The gift was to be shared by both the club and the societies, with $450,000 for the Engineers' Club and $1,050,000 for the engineering societies.[62][69] Carnegie's gift only covered the costs of the respective buildings, and the club and societies had to buy their own respective land lots.[65] The Engineers' Realty Company formally transferred the land to the Engineers' Club in August 1904.[72] The Engineers' Club site cost $225,000.[73]

Design and construction[edit]

After Carnegie's gift, the ASME, AIME, AIEE, and Engineers' Club formed a Conference Committee to plan the new buildings.[68] Because of Carnegie's international fame and his large gift, the design process was to be "a semi-public matter of more than ordinary importance".[62][69] The Conference Committee launched an architectural design competition in April 1904, giving $1,000 each (about $27,232 in 2023) to six longstanding architecture firms who submitted plans.[68][74][b] Other architects were allowed to submit plans anonymously and without compensation. Any architect was eligible if they had actually practiced architecture under their real name for at least two years. The four best plans from non-invited architects would receive a monetary prize.[c] William Robert Ware was hired to judge the competition.[69][74]

That July, the committee examined over 500 drawings submitted for the two sites.[62][75][d] Whitfield & King, a relatively obscure firm that had nonetheless been formally invited,[69] won the commission for the Engineers' Club Building.[75][76] Nepotism may have been a factor in the Engineers' Club commission, as Carnegie was married to Whitfield's sister Louise.[24][77] Hale & Rogers and Henry G. Morse, who had not been formally invited, were hired to design the Engineering Societies' Building.[75][76]

By September 1904, the Engineers' Club site was being demolished by the F. M. Hausling Company, and Whitfield & King were preparing the plans.[78] Plans for the Engineers' Club Building were filed with the New York City Department of Buildings in January 1905, with a projected cost of $500,000.[79][80][81] After the site had been cleared, work began on the steel frame in September 1905.[82] During an informal ceremony on December 24, 1905, Louise Carnegie laid the building's cornerstone, which contained a capsule filled with various contemporary artifacts.[83][84] The architects, high-ranking club officials, and Andrew Carnegie attended the ceremony.[85][86] At the time, the steel frame had reached the ninth story and the facade had been built to the third.[83][84] Despite a steelworkers' strike in early 1906 and a plasterers' strike that November,[19][62] the work was completed on schedule.[69] The Mechanical Engineers' Library Association leased some office space in the Engineers' Club Building.[87]

Clubhouse[edit]

The clubhouse opened on April 25, 1907, with a ceremony attended by 1,500 guests.[48] The new clubhouse involved an expenditure of $870,000, of which the building itself cost $550,000.[69] In addition to the $225,000 cost of the site, the club members had to raise $175,000.[39] Media of the time described the clubhouse as "the finest in the country".[48][88] A journal from the time described the club as having 1,750 members and a "long waiting list".[39] The Engineers' Club Building was formally dedicated on December 9, 1907, with a humorous speech by Mark Twain.[89][90] The club's members over the years included Carnegie himself, as well as Nikola Tesla, Thomas Edison, Henry Clay Frick, Herbert Hoover, Charles Lindbergh, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Henry Herman Westinghouse.[91]

1900s to 1940s[edit]

In its early years, the building held events such as an exhibition of impressionist art,[92] a dinner discussing the City Beautiful movement,[93] and a meeting in which Edison refused the 1911 Nobel Prize for physics as an "award for poor inventors".[94] By 1909, the club had 2,000 members, a 35 percent increase from three years prior.[24][95] In a report issued by the club's Board of Management the following year, the board noted that the maximum membership had been reached.[95] The board recommended that new facilities be erected for the growing membership.[24] In 1913, plans were filed for a six-story addition at 23 West 39th Street, above the carriage entrance of the Engineering Societies' Building. This structure was to contain bedrooms, bathrooms, and a restaurant.[96][97] The addition was designed by Beverly King.[17][19][97] The United Engineering Societies agreed to let the Engineers' Club use the eastern wall of the Engineering Societies' Building as a load-bearing wall. The parties also agreed to share the walkways behind both buildings and construct a steel-and-glass loading dock for freight.[19]

The 39th Street annex opened in April 1915 and the clubhouse continued to be used for major events afterward.[98] The clubhouse was flooded in April 1917 due to a water main break on 40th Street.[99][100] The clubhouse's top floors were damaged in a fire in December 1919, causing $100,000 worth of damage to the building.[101] The clubhouse continued to expand in later years.[17][98] In 1920, the Engineers' Club purchased a house at 36 West 40th Street in 1920 from the Janeway family,[102][103] intending to use the site as offices.[104] Three years later, the club purchased 28 West 40th Street from the Wylie family.[105] Number 36 was used as an office and stores and number 28 was used as a lounge and additional bedrooms.[19][17] Clubhouse activities included a 1924 speech where Charles Algernon Parsons suggested digging a 12-mile shaft for scientific research,[106] as well as a 1925 viewing of a lunar eclipse.[107][108]

The Engineers' Club proposed yet again to expand its facilities in 1936, this time erecting a 16-story office building on the adjacent site at 28 West 40th Street.[109][110] This expansion was never built.[19] In 1946, the company of the late architect Thomas W. Lamb was hired to design a renovation for the Engineers' Club Building. This prompted the New York state government to accuse Lamb's company of practicing architecture illegally;[111][112] these charges were ultimately dropped.[113]

1950s to 1970s[edit]

By the 1950s, the Engineering Societies' and Engineers' Club buildings were becoming overburdened, in large part due to their own success. A 1955 New York Times article described the buildings as "the engineering crossroads of the world", with the Engineers' Club hosting diners and overnight guests from around the world.[18] The engineering societies in the neighboring 39th Street building had originally considered moving to Pittsburgh. By 1956, the societies were instead planning to stay at 39th Street, constructing an entrance from 40th Street on property owned by the Engineers' Club.[114][115] The engineering societies ultimately sold their building in 1960.[91][116] This marked the decline of the old engineering center that had been centered around Bryant Park.[91]

An oil portrait of Herbert Hoover was dedicated at the clubhouse in 1963 and hung on a wall in a hallway there, which was named in Hoover's memory.[117] The clubhouse continued to host events in the 1960s and 1970s, such as a speech on donating engineering books to developing countries[118] and a discussion on electric traffic signals.[119] By 1972, Mechanical Engineering said the club "looks confidently toward the future".[23] At the time, the Engineers' Club was the only remaining clubhouse on the block.[23][91] Even so, the club was experiencing financial difficulties during this time.[91] The Engineers' Club finally declared bankruptcy in June 1977,[120] and was forced to liquidate many of its furnishings and decorations over the next year.[50] The club also put its main clubhouse and its three auxiliary buildings, at 28 and 36 West 40th Street and 23 West 39th Street, for sale.[91]

Residential era[edit]

In 1979, developer David Eshagin bought the Engineers' Club Building, who converted it to residential use under plans by architect Seymour Churgin.[23][116] The attic units were converted into penthouses that covered more of the roof than in the original design.[91] Some of the original spaces were preserved, including the main staircase between the first and third stories, as well as some of the larger communal spaces, which were used as hallways.[23][116] The taller spaces were divided into duplex apartments with sleeping accommodations on balconies; a New York Daily News article described the apartments as "strangely shaped" but having "a great deal more character than the usual bland shoeboxes of most New York apartments".[121] The redeveloped building was initially called "The Columns", after the columns at its base, and it had ground-floor storefronts.[91] By 1981, one of the ground-floor storefronts contained a florist.[122]

The building was further converted to a housing cooperative in 1983.[23][91][116] The penthouses above the twelfth story, dating from 1980, were expanded to duplex apartments circa 1992.[25] The facade was degrading by the 1990s, and Midtown Preservation was hired to restore the facade. The co-op originally wished to reuse the marble, but this proved impractical when the stone broke apart while the restorers were removing the stone.[23] Afterward, the marble on the facade was replaced with fiberglass, although the marble staircase inside remained intact.[123] The cornices above the third story, as well as the eleventh-story balcony, were replaced with fiberglass.[23][124] In addition, the twelfth-story keystones, arches, and cornice were replaced.[91] The restoration cost $350,000 in total.[23] The exterior was further restored in 2001.[91]

In the 21st century,[91][123] the Engineers' Club Building came to be known as an 82-unit co-op called Bryant Park Place.[32][34] In 2007, the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places, along with the Engineering Societies' Building, as the "Engineering Societies' Building and Engineers' Club".[125] The same year, Bryant Park Place's co-op board placed a plaque to the left of the main entrance, outlining the building's history.[126] By 2010, Bryant Park Place contained a women's clothing shop, SoHo Woman on the Park.[123] The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the Engineers' Club Building as a city landmark on March 22, 2011.[127][128] While the exterior is protected under landmark status, the interiors are not protected and have been altered.[32]

See also[edit]

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The ASCE had also been invited to join the Engineering Societies Building but declined, preferring to stay at its clubhouse at 220 West 57th Street.[67]

- ^ These firms were Ackerman & Partridge, Carrère and Hastings, Clinton and Russell, Lord and Hewlett, Palmer & Hornbostel, and Whitfield & King.[19][68][74]

- ^ The compensation has variously been cited as $200[74] or $400 per runner-up prize.[68][75]

- ^ The number of submissions has been cited as 26[62][75] or 28.[69]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ a b "Cultural Resource Information System (CRIS)". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. November 7, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 2011, p. 1.

- ^ a b c "30 West 40 Street, 10018". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c d White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Palatial Home and Workshops for New York Engineers; Plans for Engineers' Club and Engineering Building to be Erected by Andrew Carnegie – Luxurious Libraries, Living Quarters, and Assembly Halls" (PDF). The New York Times. September 4, 1904. p. 26. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f National Park Service 2007, p. 7.

- ^ National Park Service 2007, p. 3.

- ^ Slatin, Peter (December 11, 1994). "Back-office structure to rise on West 40th, south of Bryant Park". The New York Times. p. R7. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 109314094.

- ^ "Building Activity in Central Zone; Two Twenty-five Story Buildings: Estimated to Cost $2,500,000 Ech, Will Occupy Madison and Fifth Avenue Corners – Hatriman National Bank to Have New Home on Delmonico Building Site". The New York Times. June 8, 1924. p. RE1. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 103383170.

- ^ "Apartments in Which Homes for Many Families Are Provided: Brownstone Fronts Have Been Swept From 40th Street Tall Buildings Now Fill Skyline on South Side of Bryant Park and Library Block Builders Still Busy". The New York Herald, New York Tribune. February 8, 1925. p. B2. ProQuest 1113242850.

- ^ a b "South of 59th Street". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 71, no. 1822. February 14, 1903. p. 301. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b "Speed in Young's Trial; Prosecution Presents Eleven Witnesses in Forty-five Minutes. Promises That the Commonwealth Will Not Introduce Mormonism into the Case". The New York Times. February 7, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ a b National Park Service 2007, p. 13.

- ^ Stern, Robert A. M.; Gilmartin, Gregory; Massengale, John Montague (1983). New York 1900: Metropolitan Architecture and Urbanism, 1890–1915. New York: Rizzoli. p. 240. ISBN 0-8478-0511-5. OCLC 9829395.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (August 4, 2002). "Streetscapes/40th Street Between Fifth Avenue and Avenue of the Americas; Across From Bryant Park, a Block With Personality". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ^ a b c d National Park Service 2007, p. 21.

- ^ a b Grutzner, Charles (January 26, 1955). "Engineer Center Strains at Seams; 39th and 40th St. Buildings Have Become Inadequate – Other Cities Beckon". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 10, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Landmarks Preservation Commission 2011, p. 13.

- ^ Pollak, Michael (July 25, 2009). "Coins in the Fountains". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ National Park Service 2007, p. 10.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 2011, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Gray, Christopher (August 13, 1995). "Streetscapes: 32 West 40th Street; At 1907 Engineers' Club, Technology Has Its Limits". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Landmarks Preservation Commission 2011, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 2011, p. 10.

- ^ a b Engineers' Club 1905, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b c d e f Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1906, p. 235.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k National Park Service 2007, p. 6.

- ^ a b Engineers' Club 1905, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1906, p. 233.

- ^ National Park Service 2007, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Cohen, Michelle (September 20, 2015). "Channel the Spirits of Tesla, Carnegie and Edison in the Former Engineers' Club HQ for $14K a month or $3.1M". 6sqft. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "Bryant Park". Tesla Memorial Society of New York. May 18, 1917. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c Horsley, Carter (October 8, 2021). "Bryant Park Place, 32 West 40th Street". CityRealty. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Engineers' Club 1905, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g National Park Service 2007, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d Engineers' Club 1905, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c Engineers' Club 1905, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f g "New Home of the Engineers' Club of New York: Permanent Quarters Made Possible by the Munificence of Andrew Carnegie". The Construction News. Vol. 23, no. 20. May 18, 1907. p. 356. ProQuest 128412544.

- ^ a b c National Park Service 2007, pp. 18–19.

- ^ "Bryant Park Engineers Club". Manhattan Sideways. April 8, 2015. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ National Park Service 2007, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b c National Park Service 2007, p. 8.

- ^ Polsky, Sara (August 19, 2011). "Midtown's Mini Versailles Seeks 'Discerning Buyer' With $645K". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ Alberts, Hana R. (April 16, 2015). "No One Wants To Buy a Gaudy Mini 'Versailles' in Manhattan". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ Bahney, Anna (October 23, 2005). "On the Market". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ a b Engineers' Club 1905, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b c "Court Sets Free Armed Italians; Staten Island Justices Refuse to Hold Them for Carrying Concealed Weapons". The New York Times. April 26, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Engineers' Club 1905, p. 8.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 2011, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e Landmarks Preservation Commission 2011, p. 4.

- ^ "Club for Engineers". The New York Times. December 6, 1888. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c d National Park Service 2007, p. 12.

- ^ "The Engineers' Club Opened". The New York Times. April 28, 1889. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "Club News and Gossip". The New York Times. October 11, 1891. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "Engineers' Club's New Home". The New York Times. November 5, 1896. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "The Engineers' Club: Its Fine Quarters in the Drayton House". New-York Tribune. October 24, 1897. p. 34. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 2011, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c d e Landmarks Preservation Commission 2011, p. 5.

- ^ Union Engineering Building 1903, p. 18.

- ^ Union Engineering Building 1903, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The Engineering Societies' Building, New York". American Architect & Building News. Vol. 91. April 13, 1907. pp. 139–140 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ "Mr. Roosevelt Sees the Grand Canyon; He Pleads for the Preservation of the Wonderful Chasm. People of Arizona Gather to Hear the President, Who Talks on Irrigation and Other Topics". The New York Times. May 7, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ a b "Notes and News: A Year Ago Central Railway Club Grain Rates Reduced An Engineers' Clubhouse Association of Railway Claim Agents International Conference of the Railroad Y. M. C. A. Picketing by Strikers Enjoined in a Federal Court Hearing in Complaint Against Coal Roads A Pennsylvania Roundhouse". The Railway Age. Vol. 35, no. 19. May 8, 1903. p. 843. ProQuest 903885883.

- ^ a b c National Park Service 2007, p. 14.

- ^ "National Clubhouse for Engineers; Andrew Carnegie to Insure Its Success With $1,000,000. Plans for Great Structure to Be Erected in This City Contemplate Auditoriums for Conventions". The New York Times. May 4, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ^ "Carnegie's Offer Refused: American Society of Civil Engineers Won't Share Union Building". The New York Times. March 3, 1904. p. 1. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 96393604.

- ^ a b c d e National Park Service 2007, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Landmarks Preservation Commission 2011, p. 6.

- ^ "Andrew Carnegie's Gift to Engineers; a Forty-word Note Places $1,500,000 at Their Disposal". The New York Times. March 16, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "Carnegie Gives Home". New-York Tribune. March 16, 1904. p. 6. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "The Building Department.: List of Plans Filed for New Structures in Manhattan and Bronx". The New York Times. August 3, 1904. p. 10. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 96415497.

- ^ "To Build in 39th-st.: Site for Union Engineering Building, Carnegie Gift, Cost $517,000". New-York Tribune. January 4, 1904. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Plans for Carnegie Home for Engineers; Competing Architects Asked to Submit Drawings Before June 15". The New York Times. April 24, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Selection of Architects for Engineering Building". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 74, no. 1896. July 16, 1904. p. 124. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b "H.D. Hale Winning Architect; Dr. E.E. Hale's Grandson Will Design United Engineering Building". The New York Times. July 14, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ National Park Service 2007, p. 16.

- ^ "Of Interest to the Building Trades". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 74, no. 1904. September 10, 1904. p. 534. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Plans for Engineers' Club Filed". New-York Tribune. January 17, 1905. p. 10. ProQuest 571630908.

- ^ "Thirteen-story Club; Engineers' Fine New Home Will Have a Roof Garden". The New York Times. January 17, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "Projected Buildings". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 75, no. 1923. January 21, 1905. p. 172. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Engineers' New Clubhouse.; Work on the Structure in West Fortieth Street Well Under Way". The New York Times. September 23, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ a b "The New Building of the Engineers' Club". The Electrical Age. Vol. 36, no. 1. January 1, 1906. p. 6. ProQuest 574359780.

- ^ a b "Laying the Engineers' Club Foundation Stone". The Construction News. Vol. 21, no. 1. January 6, 1906. p. 5. ProQuest 128408542.

- ^ "Engineers' Club Stone Laid". New-York Tribune. December 27, 1905. p. 6. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "Mrs. Carnegie Officiates". The New York Times. December 27, 1905. p. 8. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "In the Real Estate Field; Madison Avenue Property Sold – Deal for Columbus Avenue Hotel Involves Over $700,000 – Plenty of Auction Buyers for Bronx Lots". The New York Times. October 11, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "Engineers in New Home". New-York Tribune. April 26, 1907. p. 2. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "Mark Twain Jeers at Simple Spelling; Has Fun With Mr. Carnegie's System at the Dedication of the Engineers' Club". The New York Times. December 10, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ "Carnegie on Kings". New-York Tribune. December 10, 1907. p. 7. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Landmarks Preservation Commission 2011, p. 8.

- ^ "Impressionist Art at Engineers' Club; Masters of the School to Be Seen in a Notable Loan Exhibition. Etchings to Go at Auction Private Collection, Including Examples of Rembrandt and Whistler, Under the Hammer". The New York Times. March 19, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ "Tell How to Make the City Beautiful; Now Is the Time to Correct Bad Features and Provide for Future, Says Architect Lamb". The New York Times. October 21, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ "Edison Won't Take the Nobel Prize; He Regards It, Says an Associate of Many Years, as a Reward for Poor Inventors". The New York Times. November 26, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ a b Engineers Club of New York (1910). Constitution, Rules, Officers and Members of the Engineers' Club. The Club. p. 96. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Latest Dealings in the Realty Field; High Rent for Small Shop Leased in the Times Square Section". The New York Times. October 26, 1913. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ a b "Projected Buildings". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 91, no. 2356. May 10, 1913. p. 1014. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 2011, pp. 7–8.

- ^ "4-Foot Main Bursts; Floods Fine Homes". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 28, 1917. p. 22. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ "Catskill Pressure Breaks Water Main; Basements in Fortieth Street Flooded by a Geyser From Four-foot Pipe". The New York Times. April 29, 1917. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ "Engineers Club Ablaze.; Six Employes Rescued in Fire Which Did $100,000 Damage". The New York Times. December 13, 1919. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ "Costly Dwelling Houses Figure in the Buying". New-York Tribune. June 2, 1920. p. 19. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ "Real Estate Transaction 1 – No Title". New-York Tribune. April 17, 1920. p. 17. ProQuest 576220740.

- ^ "Engineers' Club Adds to Its Plot". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 105, no. 17. April 24, 1920. p. 540. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Engineers' Club Gets Realty W. 40th St". New-York Tribune. May 18, 1923. p. 22. ProQuest 1237267317.

- ^ "Suggests Sinking a 12-mile Shaft; Sir Charles Parsons Says New Elements Might Be Revealed". The New York Times. September 27, 1924. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ National Park Service 2007, p. 22.

- ^ "Watchers on Roofs to Fix Eclipse Path; Lighting Companies Here to Post Ninety Experts at Vantage Points Saturday". The New York Times. January 21, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ "Engineers Club Plans Tall Office Building". The New York Times. July 3, 1936. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ "Engineers Club to Erect Large Office Building: Plans 16-Story Structure for West 40th Street Site". New York Herald Tribune. July 3, 1936. p. 36. ProQuest 1237476166.

- ^ "Building Designer Accused by State; Illegal Practice Charged to Lamb, Inc., Planner of the Garden, Famous Theatres". The New York Times. April 24, 1947. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ "Illegal Practice Of Architecture Is Laid to Firm: State Charges T. W. Lamb Concern Lost Rights by Bankruptcy Plea in '42". New York Herald Tribune. April 24, 1947. p. 22A. ProQuest 1291290013.

- ^ "Charges Dropped Against Lamb Inc: Architects Were Accused of Illegal Practice". New York Herald Tribune. December 24, 1947. p. 2. ProQuest 1326963284.

- ^ "Engineers Bid Society Stay Here: Study Rejects Outside Offers". New York Herald Tribune. June 28, 1956. p. 13. ProQuest 1325269935.

- ^ Grutzner, Charles (June 28, 1956). "Engineer Center Likely to Remain; Special Committee of Five Societies Rejects Plan to Move to Pittsburgh". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c d National Park Service 2007, p. 23.

- ^ "Hoover Portrait Unveiled By Dewey at Club Here". The New York Times. November 15, 1963. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ "Needy Nations Seek Engineering Books". The New York Times. June 8, 1961. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ "Barnes Tells Engineers Of Plans for New Signals". The New York Times. February 3, 1966. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ "Business Records". The New York Times. June 21, 1977. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ "Midtown Accumulation". New York Daily News. October 7, 1990. p. 213. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ Taylor, Angela (September 16, 1981). "Discoveries". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c Finn, Robin (March 4, 2010). "Good Taste That Outlives the Tents". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 2, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ National Park Service 2007, p. 25.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places 2007 Weekly Lists" (PDF). National Park Service. 2007. p. 281. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 28, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 2011, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Gootman, Elissa (March 22, 2011). "Four New Landmarks Include City's Youngest". City Room. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "Engineers' Club Building Voted Midtown's Newest Landmark – Midtown & Theater District – New York". DNAinfo. March 22, 2011. Archived from the original on November 10, 2017. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

Sources[edit]

- "The Engineering Building and Engineers' Club". Architects' and Builders' Magazine. Vol. 38. W.T. Comstock. March 1906. pp. 225–235.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - "Engineering Societies' Building and Engineers' Club" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. August 30, 2007.

- "Engineers' Club" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 22, 2011.

- Engineers' Club (1905). The new club house of the Engineers' club. New York, Issued by order of the trustees – via Internet Archive.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Union Engineering Building. May 4, 1903 – via Internet Archive.

External links[edit]

- 1907 establishments in New York City

- Bryant Park buildings

- Buildings and structures completed in 1907

- Clubhouses on the National Register of Historic Places in Manhattan

- Neoclassical architecture in New York City

- New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan

- Residential buildings completed in 1907

- Residential buildings in Manhattan

- New York State Register of Historic Places in New York County