Edward Dando

Edward Dando (c. 1803 – 28 August 1832) was a thief who came to public notice in Britain because of his unusual habit of overeating at food stalls and inns, and then revealing that he had no money to pay. Although the fare he consumed was varied, he was particularly fond of oysters, having once eaten 25 dozen of them with a loaf and a half of bread with butter.

Dando began his thefts in about 1826 and was arrested at least as early as 1828. He would often leave a house of correction and go on an eating spree the same day, being arrested straight away and appearing in court within a few days, only to be put back in prison; his normal defence was that he was hungry. On at least one occasion he was placed in solitary confinement after he stole the rations of his fellow prisoners. Most of his activity was in London, although he also spent time in Kent, much of it in the county's prisons. While in Coldbath Fields Prison in August 1832, Dando caught cholera—part of a long-running pandemic—and died.

His death, like his many exploits, was widely and sympathetically reported both in the London daily press and in local newspapers. His name entered into the public argot as a term for someone who eats excessively and does not pay. He was the subject of numerous poems and ballads. In 1837 William Makepeace Thackeray wrote a short story loosely based on Dando; this was made into a play by Edward Stirling. Charles Dickens wrote about Dando and compared him to Alexander the Great.

Biography[edit]

There is little published information about Dando's early life, although he was born in around 1803 and was a hatter—possibly an apprentice.[1][2] Numerous sources give his name as Edward Dando and his nationality as British,[3][4] although the British Museum describes him as "John Dando", an American.[5]

In about 1826 Dando began the practice of eating and drinking at different food sellers without being able to afford the meal.[6] Although out of work, he refused poor relief, saying he despised it because he "had a soul above it".[7] Dando was arrested for his acts of theft at least as early as 1828. On an appearance in court in April 1830, the arresting police officer said Dando had been arrested two years previously after consuming two pots of ale and two pounds (0.9 kg) of rump steak and onions and then refusing to pay.[8][a] Dando's April 1830 arrest followed his eating 1.75 pounds (0.79 kg) of ham and beef, a half-quartern loaf, seven pats of butter and eleven cups of tea, coming to 3s 6d,[3][8] at a time when the average weekly wage for agricultural labourers was between eight and twelve shillings.[10][b][c] The magistrate sentenced him to one month at the house of correction in Brixton, Surrey, under the Vagrancy Act 1824.[3][8][d] Dando spent some time in solitary confinement after he stole bread and beef from his fellow prisoners.[3][14]

On the day of his release he walked into an oyster shop and ate thirteen dozen (156) oysters and a half-quartern loaf, washed down with five bottles of ginger beer—the ginger beer because, he said, he was troubled with wind. He was arrested and appeared in court; he explained that "I was very peckish, your Worship, after living on a gaol allowance so long, and I thought I'd treat myself to an oyster".[13] This was the second oyster shop he visited that day: in the first he ate oysters and bread to the sum of 3s 6d; the shop owner had kicked him and thrown him out of the shop. The magistrate sentenced Dando to three months in prison, and elected that it should be in the Guildford House of Correction in Surrey, which was considered to keep tougher discipline than Dando had experienced in Brixton. He warned Dando that if he repeated his crime, he faced transportation.[13][15]

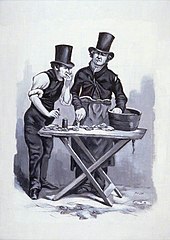

Oysters were cheap in the 1820s and 1830s and a basic food source for the poor, who bought them from oyster stalls or wheelbarrows;[6][16] in The Pickwick Papers (1836), Dickens has the character Sam Weller relate that "poverty and oysters always seem to go together", continuing "the poorer a place is, the greater call there seems to be for oysters. Look here, sir; here's a oyster-stall to every half-dozen houses. The street's lined vith 'em. Blessed if I don't think that ven a man's wery poor, he rushes out of his lodgings, and eats oysters in reg'lar desperation".[17][18] In the 1830s oysters could be bought three for a penny,[19] or for up to 1d each.[18][e] By 1840 Londoners ate 496 million oysters a year—a quarter of which were sold by street sellers.[20]

News of his next arrest and court appearance—in August 1830—was published in The Times, and followed Dando's eating eleven dozen (132) large oysters, a half-quartern loaf and eleven pats of butter without being able to pay for them. His defence was that he was hungry after his release from Guildford prison that day: "I am here at your mercy, and prepared to undergo the punishment that awaits me, whatever it may be; but I again say, that I must satisfy my hunger."[14] The magistrate did not impose a sentence on Dando and allowed him to leave. Outside the court, the owner of the oyster stall threw a bucket of water over him and beat him with his cane, "to the infinite amusement of a throng of persons who had assembled outside and who were aware of the prisoner's transgressions", according to The Times.[14][21]

Dando remained out of prison until mid-September, when he was again arrested for eating oysters without being able to pay for them. The owner of the oyster shop in Vigo Street, Piccadilly, was suspicious after Dando consumed two dozen oysters. She challenged him to pay and handed him over to the police when he admitted he could not. Dando was again sent to the house of correction.[22][23]

In early December 1830, when he was back in court again, one newspaper took to calling him "Dando, the celebrated oyster eater". His notoriety was spreading and a number of oyster sellers and food shop owners were present in court to see him. They heard that the day after Dando had been released from prison, he visited a tavern in Knightsbridge and drank sixpennyworth of brandy with two Abernethy biscuits and a pint of ale. He did not pay and was caught after fleeing; he was taken to the police station where the landlord forgave him and he was released. He went to a coffee shop where he consumed bread, butter and coffee worth 1s 6d, then ran off without paying. He went to two further inns and drank two pints of ale and 0.25 imperial pints (0.14 L) of rum. The magistrate was not sympathetic to the innkeepers and said they should have asked for their money in advance of providing the food and drink; Dando was released.[24][f]

In early January 1831 Dando was, once again, back in court for non-payment for food—on this occasion soup and bread—and once again he was imprisoned.[25] He was back in court at the end of February, in front of the magistrate Sir Richard Birnie. Having drunk two glasses of brandy in one public house in Queen Street before being thrown out, Dando then moved on to a restaurant near Temple Bar. Here he ate two plates of beef à la mode and drank brandy before it was established that he could not pay.[26] Before sentencing him to three months in prison, Birnie asked Dando about his clothing, which had been acquired at prisons; to laughter in the court, Dando explained

The jacket, I think, came from Brixton; the waistcoat ... was bestowed upon me at a similar establishment at Guildford; and the trousers I know I acquired by hard servitude in your Middlesex house of correction. I am indebted to the City authorities for the rest of my wardrobe.[6][27]

After his release Dando was arrested again and served a second three-month sentence in prison before being released in October 1831. The day after his release he went into an oyster shop in Long Lane, Bermondsey, and consumed nine dozen (108) oysters with a half-quartern loaf of bread and butter. As he had no residence, he was committed to three months' imprisonment at the Guildford House of Correction for vagrancy.[28]

Dando was found drunk in January 1832, having been released from prison four days previously. Covered in mud and with a noticeable black eye, he was imprisoned for eight days for public drunkenness.[29] At the end of March he was again arrested, but was discharged. Some attendees in court gave him money to tell them his story, and his tale was duly reported in the press. He explained that he had begun living by stealing food some six years previously and that, if he had a respectable suit of clothes, he could make his way in the world. He reported that he had received numerous beatings for his actions, including one a few weeks previously at Kennington that he would never forget. He received the punishment when he had eaten four dozen (48) oysters with bread and butter and could not pay; he was dragged through a pond, beaten with cudgels and kicked. He said that the tales of his extravagant eating had been exaggerated, and that the most he had ever eaten was 25 dozen (300) oysters with a loaf and a half of bread with butter; he thought he could probably eat 30 dozen (360) oysters.[2][6][7] Dando thought he did no wrong in his actions which he justified by stating:

I refuse to starve in a land of plenty. Instead I shall follow the example of my betters by running into debt without having the means of paying. Why, some men live in great extravagance and luxury, owe money and cheat their creditors, yet they are still considered respectable and honest. I only run into debt to satisfy the craving of hunger, and yet I am despised and beaten.[30]

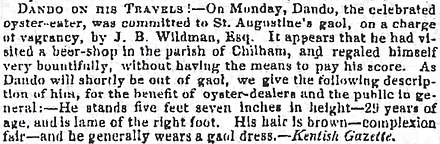

In June 1832 Dando was arrested in Kent after drinking at an inn in the parish of Chilham without paying; he was imprisoned for vagrancy and a description of him appeared in the press, describing him as 5 feet 7 inches (1.70 m), brown haired with a pale complexion and lame in the right foot.[7][31]

After spending time in Kent, Dando returned to London and, after a few days, was arrested and sent to Coldbath Fields Prison. He caught cholera there—part of the long-running pandemic—and died on 28 August 1832.[6][32][g] His burial was the following day; Dickens later imagined that Dando "was buried in the prison yard and they paved his grave with oyster shells".[33] His death was noted in the press, including The Times and The Observer.[34][35]

Cultural legacy[edit]

Dando's exploits were widely reported in the press, both in the London dailies and reprinted in local newspapers. The historian Christopher Impey describes much of the reportage as "romanticised";[6] the academic Ann Featherstone considers their tone "was half-amused, half amazed".[36] Featherstone believes that Dando "had a sharp wit and an easy manner and provided reporters with striking quotes",[37] which helped their sympathetic tone, and his "audacity [which] drew a sneaking admiration from the more cynical newspaper men".[38]

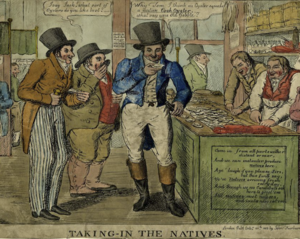

In addition to the newspaper eulogies and obituaries, mostly humorous or whimsical,[39] after Dando's death there were numerous poems and street ballads written about him, as well as several caricatures.[40][41] Among the ballads published was "The Life and Death of Dando, the Celebrated Oyster Glutton" by James Catnach:

One day he walk'd up to an oyster stall.

To punish the natives, large and small;

Just thirty dozen he managed to bite,

With ten penny loaves—what an appetite!

But when he had done, without saying good day,

He bolted off, scot free, away;

He savag'd the oysters, and left the shell—

Dando, the bouncing, seedy swell.[42][43]— James Catnach, "The life and death of Dando, the celebrated oyster glutton"

In 1837 William Makepeace Thackeray wrote "The Professor", a short story loosely based on Dando.[44][45] The short story was made into a play, Dandolo; or, the Last of the Doges, by Edward Stirling in 1838, which was staged at the City of London Theatre.[40][46]

Dando's name entered common argot as a word to describe someone who ate at food outlets and did not pay. An 1878 dictionary of slang terms described a dando as "a great eater, who cheats at hotels, eating shops, oyster-cellars, etc, from a person of that name who lived many years ago, and who was an enormous oyster eater".[47] In 1850 the Whig politician Thomas Macaulay wrote "I was a Dando at a pastry-cook's, and then at an oyster shop",[48] although he did not clarify whether he just ate too much, or whether he also did not pay.[4] In The Book of Aphorisms, published by the Scottish writer Robert Macnish in 1834, Dando appears four times,[49] including in aphorism 405, which states that oysters should be eaten raw: "depend upon it, this is the approved method among gourmands. My lamented friend, the late Dando, never swallowed them in any other form".[50]

The academic Rebecca Stott considers that Dando is often portrayed "as a kind of folk hero, transgressing the law to follow his singular passions. A kind of oyster-eating pirate living outside the law."[51] During the period when Dando was active, Britain's social and economic situation was in upheaval, with high unemployment, poverty and civil unrest such as the Swing Riots. Featherstone, commenting on Dando's "I refuse to starve in a land of plenty" philosophy, sees the background of the Swing Riots as pertinent to his lifestyle.[52] In 1867 the Tory-leaning literary journal Fraser's Magazine wrote that it thought Dando's philosophy had been plagiarised by the Tory politician Benjamin Disraeli. The journal quoted Dando: "oysters were meant for mankind; don't talk to me of a property acquired by paying for them. So long as oysters exist, I will eat as many as I see fit" and compared this philosophy unfavourably with what they perceived to be Disraeli's flexible political positions: "Principles were meant for mankind; don't talk to me of a property acquired by believing in them. So long as principles exist, I will use them in any way, profess them or disclaim them, as I see fit."[53]

The writer Charles Dickens, a great lover of oysters and oyster culture,[54] kept up a correspondence with the American educator Cornelius Felton. In a letter from July 1842, Dickens gave Felton a potted history of Dando, in which he wrote "he has been known to eat twenty dozen at one sitting, and would have eaten forty, if the truth had not flashed upon the shopkeeper".[55] In his literary magazine All the Year Round Dickens compared Dando with Alexander the Great, writing that "Alexander wept at having no more worlds to conquer, and Dando died because there were no more oyster-shops to victimise."[56] One anonymous writer chose to celebrate Dando with the lines:

On some far-distant shores,

There are who seek the oyster for the pearl;

She sometimes brings with her a priceless dower—

But Dando only sought her for herself.

See also[edit]

- Dine and dash

- Making off without payment, offence introduced by the Theft Act 1978

- Tarrare

- Charles Domery

Notes and references[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ A pot of ale held one imperial quart (2.0 imperial pints; 1.1 litres; 38 US fluid ounces).[9]

- ^ By law, a half-quartern loaf had to weigh two pounds (0.91 kg).[11]

- ^ 3s 6d equates to approximately £16.67 in 2021, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[12]

- ^ It is possible that Dando spent time on the penal treadmill; the magistrate at his next trial made reference to the possibility.[13]

- ^ A pre-decimal penny equates to approximately £0.38 in 2021, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[12]

- ^ Sixpence equates to approximately £2.38 and 1s 6d equates to approximately £7.14 in 2021, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[12]

- ^ The pandemic was particularly bad in London that year: 6,000 people died.[32]

References[edit]

- ^ Matthewman 2021.

- ^ a b "Life of Dando". The Ballot, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d Impey 2019, p. 51.

- ^ a b Neild 1995, p. 4.

- ^ "John Dando". British Museum.

- ^ a b c d e f Impey 2019, p. 52.

- ^ a b c d "Caution to shell fish dealers, publicans &c". The Observer, p. 1.

- ^ a b c "Police". The Morning Gazette, p. 3.

- ^ Cherrington 1925, p. 140.

- ^ Bowley 1900, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Smith 2013, p. 192.

- ^ a b c Clark 2023.

- ^ a b c "Union Hall—A Glutton". The Morning Advertiser, p. 4.

- ^ a b c "Union Hall". The Times, p. 4.

- ^ "Union Hall". John Bull, p. 163.

- ^ Richardson 2008, p. 28.

- ^ Dickens 1837, pp. 227–228.

- ^ a b Schlicke 2011, p. 389.

- ^ Freeman 1989, p. 30.

- ^ Taverner 2023, p. 73.

- ^ Featherstone 2013, 1462.

- ^ "Police". Morning Advertiser (September 1830), p. 4.

- ^ "Astonishing the natives". John Bull, p. 298.

- ^ "Queen Square—A night's adventure of Master Dando, the celebrated oyster eater". Morning Advertiser, p. 4.

- ^ "The Gourmand". Morning Advertiser, p. 4.

- ^ "Bow Street". Morning Advertiser, p. 4.

- ^ "Untitled". The Observer, p. 3.

- ^ "Police". Morning Advertiser (October 1831), p. 4.

- ^ "Police Intelligence". Morning Post, p. 4.

- ^ Featherstone 2013, 1448.

- ^ "Untitled". The Times, p. 30.

- ^ a b Featherstone 2013, 1517.

- ^ Impey 2019, p. 53.

- ^ "Death of Dando, the notorious oyster-eater". The Times, p. 2.

- ^ "Death of the renowned gourmand, Dando". The Observer, p. 2.

- ^ Featherstone 2013, 1469.

- ^ Featherstone 2013, 1497.

- ^ Featherstone 2013, 1474.

- ^ Featherstone 2013, 1528.

- ^ a b Hindley 1878, p. 335.

- ^ Stott 2004, p. 84.

- ^ Hindley 1878, p. 336.

- ^ Hodgson 1887, p. 17.

- ^ Featherstone 2013, 1472.

- ^ Harden 1998, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Stirling 1838, p. 1.

- ^ Hotten 1874, p. 139.

- ^ Macaulay 1878, p. 281.

- ^ Macnish 1834, pp. 79, 96, 138, 199.

- ^ Macnish 1834, p. 138.

- ^ Stott 2004, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Featherstone 2013, 1454.

- ^ "The Conservative transformation". Fraser's Magazine, pp. 662–663.

- ^ Neild 1995, p. 3.

- ^ Dickens 1909, p. 71.

- ^ Dickens 1861, p. 544.

- ^ "Dando, the oyster-eater". Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, pp. 613–614.

- ^ "Dando, the oyster-eater". Digital Victorian Periodical Poetry.

Sources[edit]

Books[edit]

- Bowley, A. L. (1900). Wages in the United Kingdom in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 906236739.

- Cherrington, Ernest Hurst, ed. (1925). Standard Encyclopedia of the Alcohol Problem. Vol. I Aarau-Buckingham. Westerville, OH: American Issue Pub. Co. OCLC 935332803.

- Dickens, Charles (1837). The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. London: Chapman and Hall. OCLC 28228280.

- Dickens, Charles (1909). Hogarth, Georgina; Dickens, Mamie (eds.). The Letters of Charles Dickens. London: Macmillan. OCLC 4810241.

- Featherstone, Ann (2013). "Dando the Oyster-Eater: The Life and Times of a Bouncing, Seedy Swell on a Bilking Spree". In Bradshaw, Ross (ed.). Crime (Kindle ed.). Nottingham: Five Leaves. Location 1448–1552. ISBN 978-1-9078-6998-3.

- Freeman, Sarah (1989). Mutton and Oysters: The Victorians and Their Food. London: Gollancz. ISBN 978-0-575-03151-7.

- Harden, Edgar F. (1998). Thackeray the Writer: From Journalism to Vanity Fair. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-3337-1045-6.

- Hindley, Charles (1878). The Life and Times of James Catnach (late of the Seven Dials), Ballad Monger. London: Reeves and Turner. OCLC 1114759603.

- Hodgson, Orlando (1887). The Free & Easy, or Convivial Songster. London: O. Hodgson. OCLC 1057729150.

- Hotten, John Camden (1874). The Slang Dictionary: Etymological, Historical and Anecdotal. London: Chatto and Windus. OCLC 669684221.

- Impey, Christopher (2019). The House on the Hill. Brixton: London's Oldest Prison. London: Tangerine Press. ISBN 978-1-9106-9142-7.

- Macaulay, Thomas (1878). Trevelyan, George (ed.). The Life and Letters of Lord Macaulay (PDF). Vol. 2. London: Longmans, Green & Co. OCLC 984715856.

- Macnish, Robert (1834). The Book of Aphorisms. Glasgow: W. R. McPhun. OCLC 1190970981.

- Neild, Robert (1995). The English, the French and the Oyster. London: Quiller Press. ISBN 978-1-8991-6312-0.

- Richardson, Albert Edward (2008) [1931]. Georgian England: a Survey of Social Life Trades, Industries & Art From 1700 to 1820. London: JM Classic Editions. ISBN 978-1-906600-00-6.

- Schlicke, Paul, ed. (2011). The Oxford Companion to Charles Dickens. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1996-4018-8.

- Smith, Edward (2013). Foods. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-21563-6.

- Stirling, Edward (1838). Dandolo; or, the Last of the Doges: An Original Farce in One Act. London: W. Strange. OCLC 9241894.

- Stott, Rebecca (2004). Oyster. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-8618-9221-8.

- Taverner, Charlie (2023). Street Food: Hawkers and the History of London. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1928-4694-5.

Journals and magazines[edit]

- "The Conservative transformation". Fraser's Magazine. Vol. 76, no. 455. London: Longmans, Green & Co. November 1867. pp. 654–669.

- Dickens, Charles (16 March 1861). "Oysters". All the Year Round. Vol. 4, no. 99. London: Chapman & Hall. pp. 541–547.

- "Dando, the oyster-eater". Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine. Vol. 88, no. 541. Edinburgh: W. Blackwood. November 1860. pp. 613–615.

News[edit]

- "Astonishing the natives". John Bull. 19 September 1830. p. 298.

- "Bow Street". Morning Advertiser. 25 February 1831. p. 4.

- "Caution to shell fish dealers, publicans &c.—Dando, the oyster-eater—abroad". The Observer. 24 June 1832. p. 1.

- "Death of Dando, the notorious oyster-eater". The Times. 31 August 1832. p. 2.

- "Death of the renowned gourmand, Dando". The Observer. 2 September 1832. p. 2.

- "The Gourmand". Morning Advertiser. 5 January 1831. p. 4.

- "Life of Dando". The Ballot. 1 April 1832. p. 4.

- "Police". The Morning Gazette. 16 April 1830. p. 3.

- "Police". Morning Advertiser. 14 September 1830. p. 4.

- "Police". Morning Advertiser. 6 October 1831. p. 4.

- "Police Intelligence". Morning Post. 27 January 1832. p. 4.

- "Queen Square—A night's adventure of Master Dando, the celebrated oyster eater". Morning Advertiser. 6 December 1830. p. 4.

- "Union Hall". John Bull. 24 May 1830. p. 163.

- "Union Hall". The Times. 20 August 1830. p. 4.

- "Union Hall—A Glutton". The Morning Advertiser. 18 May 1830. p. 4.

- "Untitled". The Observer. 27 February 1831. p. 3.

- "Untitled". The Times. 25 June 1832. p. 5.

Websites[edit]

- Clark, Gregory (2023). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- "Dando, the oyster-eater". Digital Victorian Periodical Poetry. University of Victoria. Archived from the original on 12 June 2023. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- "John Dando". British Museum. Archived from the original on 17 June 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- Matthewman, Scott (15 July 2021). "Luke Wright: The Ballad Seller". The Reviews Hub. Archived from the original on 5 February 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2023.