Tell Sheikh Hamad

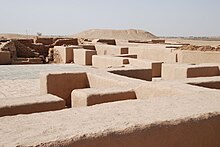

Ruins of the "Red House" of Tell Sheikh Hamad exposed by excavations (6th century AD) | |

| Location | Syria |

|---|---|

| Region | Al-Hasakah Governorate |

| Coordinates | 35°38′36″N 40°44′25″E / 35.64333°N 40.74028°E |

Tell Sheikh Hamad (Arabic: تل الشيخ حمد), also Dur-Katlimmu, is an archeological site in eastern Syria on the lower Khabur River,[1] a tributary of the Euphrates.

Chalcolithic Period

[edit]

The site of Tell Sheikh Hamad was occupied from the Late Chalcolithic period (Late Neolithic, M4), when it was a small settlement.[2]

Late Bronze

[edit]Mitanni Period

[edit]In the Late Bronze Age, the region surrounding Dur-Katlimmu was part of the Mitanni Empire and the kingdom of Hanigalbat. Following the fall of the stronghold Carchemish to Suppiluliuma of the Hittites, and the assassination of great king Tushratta in 1345 BC, the Mitanni Empire struggled with civil war and outside pressure until it fell. A quantity of Hittite potter was found at the site.[3]

Assyrian Period

[edit]During the reign of Shalmaneser

[edit]The city was established as the capital of a new Assyrian province by Shalmaneser I (r. 1263-34 B.C.) following the collapse of the Mitanni Empire. He put Ibašši-ilī son of Adad-nirari I, his brother, as the founder of the dynasty on the royal throne. Dur-Katlimmu (Tell Seh Hamad) became the capital of this kingdom on the lower Habur river. The ruler bore the title 'grand vizier' (sakallu rabi'u) and 'king of the land of Hanigalbat' (sar mat Hanigalbat).[4]

Iron Age

[edit]Neo-Assyrian Period

[edit]End of the Assyrian Empire

[edit]During the fall of the Assyrian Empire (911-605 BC), sections of the Assyrian army retreated to the western corner of Assyria after the fall of Nineveh, Harran and Carchemish, and a number of Assyrian imperial records survive between 604 BC and 599 BC in and around Dur-Katlimmu, and so it is possible that remnants of the Assyrian administration and army still continued to hold out in the region for a few years.[5]

After the fall of the Assyrian Empire

[edit]After the fall of the Assyrian Empire, Dur-Katlimmu became one of the many Near- and Middle-Eastern cities called Magdalu/Magdala/Migdal/Makdala/Majdal, all of which are simply Semitic language toponyms meaning "fortified elevation, tower".[1][6]

Excavations

[edit]In 1878 Hormuzd Rassam dug some test trenches and removed a stele fragment.[7] The site was excavated between 1978 and 2010, led by Hartmut Kühne .[8]

Excavations have recovered 550 cuneiform Akkadian and 40 Aramaic texts belonging to a senior guard of Ashurbanipal.

In July 2020, French archaeologists excavated Tell Sheikh Hamad during the Syrian Civil War, according to the Anadolu Agency.[9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Kühne, Hartmut, ed. (2005), Magdalu/Magdala: Tall Seh Hamad von der postassyrischen Zeit bis zur römischen Kaiserzeit, Volume 1, Berichte der Ausgrabung Tall Seh Hamad/Dur-Katlimmu, Berlin: Harrassowitz.

- ^ Bryce, Trevor; Birkett-Rees, Jessie (2016). Atlas of the Ancient Near East: From Prehistoric Times to the Roman Imperial Period. Routledge. p. 99. ISBN 9781317562108.

- ^ Pfalzner, P. 1995. Mittanische und Mittelassyrische Keramik. Berlin

- ^ YAMADA Masamichi, « The second military conflict between ‘Assyria' and ‘Ḫatti' in the reign of Tukulti-Ninurta I », Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale, 2011/1 (Vol. 105), p. 199-220. DOI : 10.3917/assy.105.0199. URL : https://www.cairn.info/revue-d-assyriologie-2011-1-page-199.htm

- ^ Parpola, S.; Whiting, R.M., eds. (1997), Assyria, 1995, (Symposium Proceedings), Helsinki: Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project.

- ^ cf. Hoffmeier, James Karl; Millard, Alan Ralph, eds. (2004), The Future of Biblical Archaeology: Reassessing Methodologies and Assumptions, (Symposium Proceedings), Grand Rapids: Eerdmanns, p. 105.

- ^ Rassam, H. (1897): Asshur and the Land of Nimrod, being an account of the discoveries made in the ancient ruins of Nineveh, Asshur, Sepharvaim, Calah, Babylon, Borsippa, Cuthah, and Van, incl. a narrative of different journeys in Mesopotamia, Assyria, Asia Minor, and Koordistan, Cincinnati.

- ^ Kühne, Hartmut, ed., "The Citadel of Dur-Katlimmu in Middle and Neo-Assyrian Times" (3 Volumes: Harassowitz Verlag, Berichte der Ausgrabung Tall Šēḫ Ḥamad / Dūr-Katlimmu vol. XII, 2021). ISBN 978-3-447-06168-1

- ^ "French archaeologists conduct excavations in Syria". Anadolu Agency. 15 July 2020.