Dracula (1924 play)

| Dracula | |

|---|---|

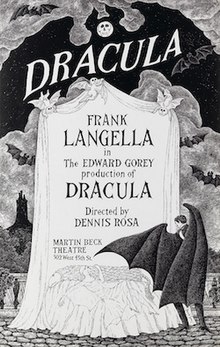

Poster for the 1977 revival of Dracula, with art by Edward Gorey | |

| Written by |

|

| Based on | Dracula by Bram Stoker |

| Characters | |

| Date premiered | 5 August 1924 |

| Place premiered | Grand Theatre, Derby, England |

| Original language | English |

| Setting | Purley, England, in the 1920s |

Dracula is a stage play written by the Irish actor and playwright Hamilton Deane in 1924, then revised by the American writer John L. Balderston in 1927. It was the first authorized adaptation of Bram Stoker's 1897 novel Dracula. After touring in England, the original version of the play appeared at London's Little Theatre in July 1927, where it was seen by the American producer Horace Liveright. Liveright asked Balderston to revise the play for a Broadway production that opened at the Fulton Theatre in October 1927. This production starred Bela Lugosi in his first major English-speaking role.

In the revised story, Abraham Van Helsing investigates the mysterious illness of a young woman, Lucy Seward, with the help of her father and fiancé. He discovers she is the victim of Count Dracula, a powerful vampire who is feeding on her blood. The men follow one of Dracula's servants to the vampire's hiding place, where they kill him with a stake to the heart.

The revised version of the play went on a national tour of the United States and replaced the original version in London. It influenced many subsequent adaptations, including the popular 1931 film adaptation starring Lugosi. A 1977 Broadway revival featured art designs by Edward Gorey and starred Frank Langella. It won the Tony Award for Best Revival and led to another film version, also starring Langella.

History

[edit]Background

[edit]The Irish author Bram Stoker wrote the novel Dracula while working as a manager for Henry Irving's Lyceum Theatre in London; he continued to work for Irving after it was published in May 1897. Stoker secured his theatrical rights to the story that same month by holding a staged reading at the Lyceum; this hasty adaptation was never performed again.[1] In 1899, Hamilton Deane, a young Irish actor whose family owned an estate next to one belonging to Stoker's father, joined Irving's company. In the early 1920s, after both Irving and Stoker had died, Deane founded his own theatrical troupe, the Hamilton Deane Company. He began working on a theatrical version of Dracula in 1923, and in 1924 he secured the permission of Stoker's widow Florence to stage an authorized adaptation.[2][3] At the time, Florence Stoker was engaged in a copyright dispute with the German film studio Prana Film over the film Nosferatu, which adapted the plot of Dracula without authorization, and she needed the money from the play royalties.[4][5] Deane's play was the first dramatization authorized by Stoker's estate.[6][a]

Original production

[edit]To stage the production, Deane was required to submit the completed script to the Lord Chamberlain for a license under the Theatres Act of 1843. The play was censored to limit violence – for example, the count's death could not be shown to the audience – but was approved on 15 May 1924.[8]

Deane's Dracula premiered on 15 May 1924 at the Grand Theatre in Derby, England.[9] Deane had originally intended to play the title role himself but opted for the role of Van Helsing. This production toured England for three years before settling in London, where it opened at the Little Theatre in the Adelphi on 14 February 1927.[10] It later transferred to the Duke of York's Theatre and then the Prince of Wales Theatre to accommodate larger audiences.[11]

Broadway production

[edit]

In 1927 the play was brought to Broadway by producer Horace Liveright, who hired John L. Balderston to revise the script for American audiences. In addition to radically compressing the plot, Balderston reduced the number of significant characters. Lucy Westenra and Mina Murray were combined into a single character, making John Seward Lucy's father and disposing of Quincey Morris and Arthur Holmwood. In Deane's original version, Quincey was changed to a woman to provide work in the play for more actresses.

Directed by Ira Hards with scenic design by Joseph A. Physioc, Dracula opened on 5 October 1927 at the Fulton Theatre in New York City. It closed on 19 May 1928 after 261 performances. The Broadway production starred Bela Lugosi in his first major English-speaking role; Edward Van Sloan as Van Helsing; and Dorothy Peterson as Lucy Seward.[12] Raymond Huntley, who had performed the role of Dracula for four years in England, was engaged by Liveright to star in the U.S. touring production. The national tour began on 17 September 1928 in Atlantic City, New Jersey.[13]

1951 UK tour

[edit]By the late 1940s, Lugosi's movie career had stalled, and he hoped to revive it by successfully bringing Dracula back to the West End. Producers John C. Mather and William H. Williams staged a touring production across the UK. It premiered at the Theatre Royal, Brighton on 30 April 1951. Lugosi's involvement got considerable press coverage, but the production received little interest from London theatres and never appeared on the West End. The tour ended at the Theatre Royal, Portsmouth on 13 October 1951. It was Lugosi's last performance as Count Dracula.[14][15]

1977 revival

[edit]

In 1973, the producer John Wulp staged the play with the Nantucket Stage Company in Nantucket, Massachusetts. He asked Edward Gorey, an illustrator known for his macabre, surrealist imagery, to design the sets and costumes. Gorey, who had never worked in theatre before, created a mostly black-and-white design accented with red. Dennis Rosa directed and Lloyd Battista starred as Dracula. Wulp subsequently moved the production to the off-Broadway Cherry Lane Theatre in New York.[16]

In 1976, the producer Eugene Wolsk decided to revive Dracula on Broadway, using the Gorey designs. He worked with Wulp and several co-producers, including Jujamcyn Theaters, to stage the revival.[17] The revival opened on 20 October 1977 at Jujamcyn's Martin Beck Theatre, with Rosa directing. It closed on 6 January 1980 after 925 performances.[18]

The original cast of the revival included Frank Langella as Count Dracula (later replaced by Raúl Juliá), Alan Coates as Jonathan Harker, Jerome Dempsey as Abraham Van Helsing, Dillon Evans as Dr. Seward, Baxter Harris as Butterworth, Richard Kavanaugh as R. M. Renfield, Gretchen Oehler as Miss Wells, and Ann Sachs as Lucy Seward.[19] The show won two Tony Awards for Most Innovative Production of a Revival and Best Costume Design (Edward Gorey).

The Broadway producers established a road company that toured the U.S. in 1978 and 1979, with Jean LeClerc as Dracula and George Martin as Van Helsing.[20] Jeremy Brett starred as Dracula in Denver, Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, and Chicago.[21] The U.S. revival also sparked a new production in London, where it opened on 13 September 1978 at the Shaftsbury Theatre. Terence Stamp took the title role, with Derek Godfrey as Van Helsing and Rosalind Ayres as Lucy.[22]

Plot of the play

[edit]Plot of original version by H. Deane

[edit]Jonathan Harker and Dr. Seward discuss the condition of Harker’s wife, Mina. She has had bad dreams and grows pale and weak. Dr. Seward has sent for Professor Van Helsing. They also talk about Harkers' extravagant new neighbor, Count Dracula. Harker helped him to buy property in London, including Carfax Abbey, next door to both the Harkers’ residence and to Dr. Seward’s asylum. Dracula, meanwhile, comes on a visit and hypnotizes the Harkers’ maid to do his bidding at his command. Abraham Van Helsing arrives to help with Mina’s case. Seward tells Van Helsing about Lucy Westenra, a friend of Mina's, who complained about bad dreams and had two small marks on her throat before inexplicably wasting away and dying. Seward was in love with Lucy, but she chose his friend, Lord Godalming, instead.[23] Van Helsing sends for Mrs. Harker, who tells Van Helsing about her bad dreams. Upon examination, he finds two small marks on her neck. Van Helsing also meets Harker, Godalming and Quincy Morris, a young feisty American girl and close friend of the Harkers, as well as of Godalming and Seward. Suddenly Mina tries to leave the room in a trance, saying “He is calling me," but Van Helsing stops her and persuades her to go to her room to rest. He asks Miss Morris to fetch a package he had shipped in from Holland and urges Harker and Godalming to keep an eye on Mina and to not leave her alone even for a moment. Van Helsing tells Seward that Mina has been attacked by a vampire, an undead creature that feeds on the blood of the living. They hear a commotion coming from Dr. Seward’s asylum from one of his patients called Renfield, who is obsessed with eating flies. After Seward leaves to check on him, Van Helsing is approached by Dracula. Van Helsing points to him that he didn’t notice how he entered the room, as he didn’t see his reflection in room’s mirror. Dracula considers smashing the mirror, but changes his mind. Miss Morris returns with a parcel for Van Helsing, who shows Dracula what he has prescribed for Mina - garlic flowers. This enrages Dracula, who promptly leaves.[24] Van Helsing decides to watch Mina in her sleep to catch the vampire. He invites Mina to come lie down on the couch. After Van Helsing turns off the lights, Dracula appears in the dark near Mina, expressing his pleasure of seeing her alone at last, causing her to scream. When others burst into the room and switch on the lights, Dracula has vanished. Moments later, Dracula returns through the door the others had just entered and asks if Mina is better.[25]

Van Helsing, Harker, Seward and Miss Morris gather to discuss what they have learned. Van Helsing says that Dracula is the vampire, who is causing Mina’s illness and they must stop him, but nobody else must know about it. They hear Renfield laugh and realize he has been spying on them. Renfield enters and asks to be sent away to save his soul. Mina and Godalming join the group and Renfield begs Mina to leave the place in order to save herself. Renfield is interrupted when a bat flies past, outside the window. He calls the bat "Master" and swears he is loyal. He is taken away back to his room. Van Helsing hangs garlic flowers around Mina’s neck and instructs her not to remove them. They leave Mina as she is about to go to bedroom. Suddenly she feels dizzy, the maid enters and removes the flowers. Just as the maid is about to open the window, she sees a bat flutter against the glass, trying to enter, and runs to fetch Harker. The window’s glass breaks, billowing mist creeps into the room, solidifying into Dracula as Mina looks on in horror.[26]

Three days later Godalming, Harker and Miss Morris have located and purified five of Dracula's boxes of earth, leaving the sixth in Carfax to trap the Count there. Miss Morris also points to latest newspaper describing mysterious cases of missing children, who tell stories of spending the night with a strange beautiful lady and were found in the morning with wounds on their necks. Van Helsing explains that the wounds were caused by undead Lucy and that they should put a stake through her heart to save her soul after they're done with Dracula - much to the shock of Godalming. When others leave the room, Renfield bursts in and begs remaining Dr. Seward to save him, as Dracula intends to kill Renfield for betraying him. Seward runs to fetch Van Helsing, but Dracula appears and snaps Renfield's neck, breaking his spine. Dracula wants to leave but is thwarted by Seward, Van Helsing, Godalming, Miss Morris and Harker, who block the exits and close in on Dracula. Dracula snarls at them and vanishes. The men go to Carfax, where they find Dracula in his coffin and drive a stake through his heart. Miss Morris and Mina stand in the doorway. Mina covers her face with her hands as Dracula is staked. Van Helsing says a short prayer.[27]

Plot of revised version by John L. Balderston

[edit]

John Harker visits his fiancée, Lucy Seward, at the sanatorium run by her father, Doctor Seward.[b] Abraham Van Helsing arrives to help with Lucy's case. Seward tells Van Helsing about Mina Weston, a friend of Lucy's who complained about bad dreams and had two small marks on her throat, then wasted away and died. R. M. Renfield, a lunatic patient who has been eating insects, enters and asks to be sent away to save his soul. Van Helsing waves wolfsbane at Renfield, who jumps back and becomes enraged. An attendant drags Renfield away. Lucy tells Van Helsing about her bad dreams, and he finds two small marks on her neck. Count Dracula, a visitor from Transylvania who stays nearby, arrives to offer help with Lucy. When Dracula leaves, Van Helsing tells Seward and Harker that Lucy has been attacked by a vampire, an undead creature that feeds on the blood of the living. They can exist for centuries, have supernatural powers, and hate the smell of wolfsbane. Van Helsing considers whether Dracula might be the vampire, but dismisses the idea because vampires must sleep in the soil where they were buried, and Dracula is not from England. He decides to watch Lucy in her sleep to catch the vampire. After Van Helsing turns off the lights, Dracula appears in the dark near Lucy, causing her to scream. When Van Helsing switches on the lights, they see a bat fly out the window. Moments later Dracula comes back through the door and asks if Lucy is better.

The next evening, Dracula hypnotizes Lucy's maid, saying he will send her orders. Van Helsing, Harker, and Seward gather to discuss what they have learned during the day. Harker reveals that Dracula arrived three days before Mina became ill, and he had six large boxes of Transylvanian dirt with him. Van Helsing realizes Dracula is able to stay in England by sleeping in these boxes. He says they must purify the boxes with holy water so they will no longer be usable by a vampire. They hear Renfield laugh and realize he has been spying on them. Renfield says Van Helsing's plan is the only way to save his soul and Lucy's. Renfield is interrupted when a bat flies in the room. He calls the bat "Master" and swears he is loyal. The bat flies away, and the attendant takes Renfield back to his room. After the others leave, Dracula returns and attacks Van Helsing, who repels him with a bag of sacramental bread. Van Helsing tells Seward and Harker he has proof that Dracula is a vampire. Van Helsing identifies him as “the terrible Voivode Dracula himself.”[28] He places wolfsbane and a crucifix in Lucy's room, but the hypnotized maid removes them so Dracula can enter.

The next night just before sunrise, Seward and Van Helsing have purified five of Dracula's boxes of earth, but did not find the sixth. Lucy attempts to seduce Harker and bite him, but Van Helsing stops her with a crucifix. Van Helsing plans to lure Dracula into the house and trap him there until sunrise. Dracula arrives and says he will return to his box for a century, but will then rise and claim Lucy from her grave. As the sun rises, Dracula escapes up the chimney. Renfield follows him using a hidden passage behind a bookcase. The men follow Renfield into an underground vault, where they find Dracula asleep in his box and drive a stake through his heart. After the theatre's curtain falls, Van Helsing addresses the audience with a warning that "there are such things".

Characters and cast

[edit]1924 original

[edit]

Deane's 1924 version of the play had several significant productions with different casts, including the debut production at the Grand Theatre in Derby, the initial London production at the Little Theatre, and a continuation in London at the Duke of York's Theatre, with the following casts:[10][29]

| Character | Grand Theatre | Little Theatre | Duke of York's Theatre |

|---|---|---|---|

| Count Dracula | Edmund Blake | Raymond Huntley | Raymond Huntley |

| Abraham van Helsing | Hamilton Deane | Hamilton Deane | Sam Livesey |

| Doctor Seward | Stuart Lomath | Stuart Lomath | Vincent Holman |

| Jonathan Harker | Bernard Guest | Bernard Guest | Stringer Davis |

| Mina Harker | Dora Mary Patrick | Dora Mary Patrick | Dorothy Vernon |

| Quincey P. Morris | Frieda Hearn | Frieda Hearn | Beatrice de Holthoir |

| Lord Godalming | Peter Jackson | Peter Jackson | Peter Jackson |

| R. M. Renfield | G. Malcolm Russell | Bernard Jukes | Bernard Jukes |

| Warder | Jack Howarth | Jack Howarth | W. Johnson |

| Parlourmaid | Kilda MacLeod | Kilda MacLeod | Peggy Livesey |

| Housemaid | Betty Murgatroyd | Betty Murgatroyd | Helen Adam |

1927 revision

[edit]

The 1927 revision by Balderston was first performed at the Fulton Theatre on Broadway, then opened in London at the Windsor Theatre; it was revived in 1977 at the Martin Beck Theatre on Broadway, then returned to London at the Shaftesbury Theatre, with the following casts:[30]

| Character | Fulton Theatre | Windsor Theatre | Martin Beck Theatre | Shaftesbury Theatre |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count Dracula | Bela Lugosi | Raymond Huntley | Frank Langella | Terence Stamp |

| Lucy Seward | Dorothy Peterson | Margot Lester | Ann Sachs | Rosalind Ayres |

| Abraham van Helsing | Edward Van Sloan | Edward Van Sloan | Jerome Dempsey | Derek Godfrey |

| John Harker | Terence Neill | Terence Neill | Alan Coates | Rupert Frazer |

| Doctor Seward | Herbert Bunston | Herbert Bunston | Dillon Evans | Barrie Cookson |

| R. M. Renfield | Bernard Jukes | Bernard Jukes | Richard Kavanaugh | Nickolas Grace |

| Butterworth | Alfred Frith | Carl Reid | Baxter Harris | Shaun Curry |

| Miss Wells | Nedda Harrigan | Julio Brown | Gretchen Oehler | Marilyn Galsworthy |

Dramatic analysis

[edit]Characterization of Count Dracula

[edit]Stoker's Count Dracula is old, unattractive and bestial, with pointed ears, hairy palms, and putrid breath. Deane revised the character into a suave aristocrat, who dresses formally and displays the polite manners expected in a Victorian drawing room.[31] Although the Count continues to be a foreign visitor in England, he no longer reflects negative stereotypes of eastern Europeans and Jews as he does in the novel.[32] These changes allowed Deane to have Dracula converse with the other characters on stage, rather than looming in the background as a monstrous threat.[8][33] In addition to evening clothes, Deane had Dracula wear a long cape with a high collar, which served the practical purpose of hiding the actor as he slipped through a trapdoor when the vampire was supposed to magically disappear.[31] The revised portrayal of Dracula is used by most later adaptations, including ones promoted as being faithful to the novel.[34]

Other changes from novel

[edit]Deane made several other changes from Stoker's novel in his adaptation. He streamlined the story by omitting all scenes set outside of England, including the opening sequence of Jonathan Harker visiting Transylvania and the final sequence of Dracula being chased through Europe.[35] Jonathan Harker did help Dracula to buy property in London, but he did it without ever leaving England and met the Count only after he arrived in London and became the Harkers' neighbor. At the start of the story, the Harkers are already married, Dracula is in England, and Lucy Westenra (renamed Westera in the play) is dead. The action of the play occurs primarily in the Harkers' home. To better match the actors available in Deane's company, he changed the character of Quincy Morris from a man to a woman.[36] Other characters, such as Dracula's vampire brides, were omitted. Deane also modernized the setting to the 1920s; Dracula arrives by airplane instead of a ship.[37]

Changes between original version and revised version

[edit]Balderston's revisions for the Broadway production included removing characters to reduce the total cast from eleven to eight. The characters of Arthur Holmwood and Quincey Morris (in any form) were completely removed, while Dr. Seward was aged up from one of the suitors to father of main female character.

He switched the names of female characters, now Mina character was called Lucy Seward, who is the daughter of Dr. Seward and fiancee of Jonathan Harker (named now John Harker).[38]

He changed the setting to Seward's sanatorium instead of the Harker residence.[39]

Harker now has nothing to do with bringing Dracula to England, it was some other unnamed real estate agent, who helped the Count to buy property in England. Ironically it is mentioned that Harker did visit Transylvania once and even heard some stories about Dracula’s castle, but this journey was completely unrelated to Dracula himself or his relocation to England and is simply treated as one of Harker’s many trips across Europe.

Dracula is directly said to be Vlad the Impaler - John Harker mentions, that when he was in Transylvania he heard of Castle Dracula and of a famous Voivode Dracula who lived in the castle centuries ago and fought the Turks. Van Helsing later identifies Dracula as this very Voivode. Dracula also himself says that he is 500 years old, placing his origin in the 15th century.[40]

Renfield now is not killed by Dracula.

Reception

[edit]The Era gave a positive review to the original production in 1924, calling it "very thrilling".[41] The paper also gave a positive review to the Little Theatre production in London, praising its "breathtaking excitements" and comparing it favorably to the Grand Guignol shows in Paris.[42]

Theatre Magazine complimented Peterson's performance as Lucy in the 1927 Broadway production, calling her "the lightmotif of Dracula ... [whose] fair comeliness shines through every scene like a flood of sunlight in a chamber of horrors".[43]

Adaptations

[edit]Radio adaptation

[edit]During the original Broadway run, members of the Dracula cast presented an adaptation of the play on 30 March 1928, on the short-lived NBC Radio series Stardom of Broadway. Lugosi, Van Sloan, Peterson, Neill, and Jukes performed on the 30-minute program.[44]

Films

[edit]

The 1931 Dracula film directed by Tod Browning was based on the play. The film was originally intended for Lon Chaney, who would play both the Count and the Professor--a stunt he had performed in several silent films. On his sudden death, casting the title role proved problematic. Initially, producer Carl Laemmle Jr. was not interested in Lugosi, in spite of good reviews for his stage portrayal. Laemmle instead considered other actors, including Paul Muni, Chester Morris, Ian Keith, John Wray, Joseph Schildkraut, Arthur Edmund Carewe and William Courtenay. Lugosi happened to be in Los Angeles with a touring company of the play when the film was being cast.[45] Lugosi lobbied hard and ultimately won the executives over, thanks in part to him accepting a paltry $500 per week salary for seven weeks of work, amounting to $3,500.[45][46]

Frank Langella, star of the 1977 Broadway revival, reprised the role of Count Dracula in the 1979 film version directed by John Badham.

Notes

[edit]- ^ While seeking the cinematic rights in 1930, Universal Pictures discovered a previous stage adaptation had been done in 1917, but it was unauthorized.[6] A 1921 Hungarian film, The Death of Drakula, used the character name but not the plot of the novel.[7]

- ^ Plot details are based on the 1927 revision by John L. Balderston.

References

[edit]- ^ Stuart 1994, p. 193

- ^ Steinmeyer 2013, p. 284

- ^ Melton 2011, loc 6118

- ^ Skal 2004, p. 97

- ^ Stuart 1994, p. 194

- ^ a b Skal 2004, p. 293

- ^ Skal 2004, p. 299

- ^ a b Wynne 2018, pp. 169–171

- ^ Murray, Paul (2022). "Hamilton Deane (1879–1958)". The Green Book: Writings on Irish Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Literature (20 (Samhain)): 92. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ a b Browning, John Edgar; Picart, Caroline Joan (2010). Dracula in visual media: film, television, comic book and electronic game appearances, 1921–2010 (Google Books). McFarland. ISBN 9780786462018. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ Leonard 1981, p. 508

- ^ Rhodes 2006, pp. 169–171

- ^ "Raymond Huntley in 'Dracula' Tour". Syracuse Herald. 29 July 1928. p. 32.

- ^ Rhodes 2006, pp. 185–186

- ^ Lennig 2010, pp. 377–381

- ^ Scivally 2015, loc 1105-1123

- ^ Scivally 2015, loc 1124-1153

- ^ Botto, Louis. At This Theatre: 100 Years of Broadway Shows, Stories and Stars Playbill, Inc., 2002

- ^ Eder 1977, p. C3

- ^ Leonard 1981, p. 514

- ^ Oldham, Lisa L. (22 November 1977). "Jeremy Brett - Later Stages". The British Empire. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ^ Leonard 1981, pp. 509, 514

- ^ Act 1, “Dracula The Vampire Play” by H. Deane

- ^ Act 1, “Dracula The Vampire Play” by H. Deane

- ^ Act 1, “Dracula The Vampire Play” by H. Deane

- ^ Act 2, “Dracula The Vampire Play” by H.Deane

- ^ Act 3, “Dracula The Vampire Play” by H. Deane

- ^ Act 2, “Dracula The Vampire Play” by H.Deane and J.L.Balderston

- ^ Leonard 1981, pp. 511–512

- ^ Leonard 1981, pp. 512–514

- ^ a b Scivally 2015, loc 906-910

- ^ Stuart 1994, pp. 185–186

- ^ Skal 2004, p. 107

- ^ Weber 2015, p. 197

- ^ Scivally 2015, loc 901

- ^ Skal 2004, p. 105

- ^ Kabatchnik 2009, p. 85

- ^ Melton 2011, loc 1763

- ^ Wynne 2018, p. 172

- ^ Act 2, “Dracula The Vampire Play” by H.Deane and J.L.Balderston

- ^ "Dracula". The Era. 21 May 1924. p. 10 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Dracula". The Era. 16 February 1927. p. 5 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Pretty, Blonde, Dorothy Peterson". Theatre Magazine. July 1928. p. 13.

- ^ Grams, Martin Jr. (October 2013). "The Quest for the Unholy Grail" (PDF). Radiogram. Society To Preserve and Encourage Radio Drama, Variety and Comedy. pp. 8–13.

- ^ a b DVD Documentary The Road to Dracula (1999) and audio commentary by David J. Skal, Dracula: The Legacy Collection (2004), Universal Home Entertainment catalog # 24455

- ^ Vieira, Mark A. (1999). Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. p. 42. ISBN 0-8109-4475-8.

Works cited

[edit]- Eder, Richard (21 October 1977). "Theater: An Elegant, Bloodless Dracula". The New York Times. p. C3.

- Kabatchnik, Amnon (2009). Blood on the Stage, 1925–1950: Milestone Plays of Crime, Mystery, and Detection. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6963-9.

- Lennig, Arthur (2010) [2003]. The Immortal Count: The Life and Films of Bela Lugosi. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2661-6. OCLC 642464854.

- Leonard, William Torbert (1981). Theatre: Stage to Screen to Television: Volume I: A-L. Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-1374-2. OCLC 938249384.

- Melton, J. Gordon (2011). The Vampire Book: The Encyclopedia of the Undead (Kindle ed.). Canton, Michigan: Visible Ink Press. ISBN 978-1-57859-281-4. OCLC 880833173.

- Rhodes, Gary Don (2006) [1997]. Lugosi: His Life in Films, on Stage, and in the Hearts of Horror Lovers. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-2765-5. OCLC 809669876.

- Scivally, Bruce (2015). Dracula FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the Count from Transylvania. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-1-61713-636-8. OCLC 946707995.

- Skal, David J. (2004). Hollywood Gothic: The Tangled Web of Dracula from Novel to Stage to Screen (Revised ed.). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-571-21158-6. OCLC 966656784.

- Steinmeyer, Jim (2013). Who Was Dracula?: Bram Stoker's Trail of Blood. New York: Penguin. p. 284. ISBN 978-1-101-60277-5. OCLC 858947406.

- Stuart, Roxana (1994). Stage Blood: Vampires of the 19th-century Stage. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. ISBN 0-87972-660-1. OCLC 929831619.

- Weber, Johannes (2015). "Like Some Damned Juggernaut": The Proto-filmic Monstrosity of Late Victorian Literary Figures. Bamberg, Germany: University of Bamberg Press. ISBN 978-3-86309-348-8.

- Wynne, Catherine (2018). "Dracula on Stage". In Luckhurst, Roger (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Dracula. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-15317-2. OCLC 1012744055.

Further reading

[edit]- Waller, Gregory (2010) [1986]. The Living and the Undead: Slaying Vampires, Exterminating Zombies. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07772-2. OCLC 952246731.

External links

[edit]- Dracula on the Boards at The Dracula Guide

- Dracula at National Players

- Dracula at the Internet Broadway Database